|

|

Tom at the Farm AKA Tom à la ferme (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th August 2014). |

|

The Film

Tom à la ferme / Tom at the Farm (Xavier Dolan, 2013)  The fourth feature film by young Québécois director Xavier Dolan, Tom at the Farm follows J'ai tué ma mere (I Killed My Mother, 2009), Les amours imaginaires (Heartbeats, 2010) and Laurence Anyways (2012), showing a clear progression and maturation in terms of Dolan’s style and subject matter. (Please see our reviews of I Killed My Mother here, Heartbeats here, and Laurence Anyways here.) The fourth feature film by young Québécois director Xavier Dolan, Tom at the Farm follows J'ai tué ma mere (I Killed My Mother, 2009), Les amours imaginaires (Heartbeats, 2010) and Laurence Anyways (2012), showing a clear progression and maturation in terms of Dolan’s style and subject matter. (Please see our reviews of I Killed My Mother here, Heartbeats here, and Laurence Anyways here.)

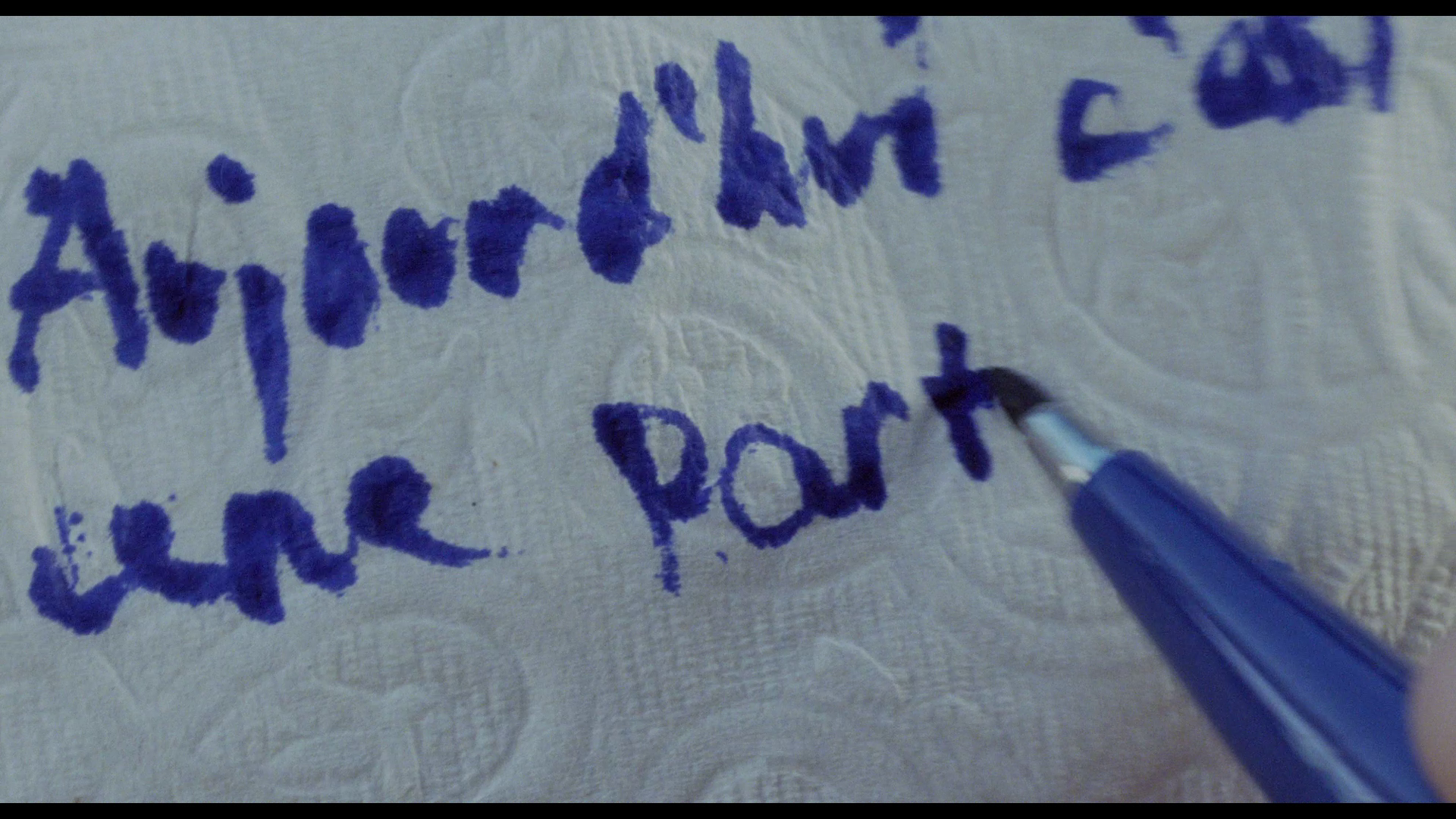

Based on Michel Marc Bouchard’s play of the same title Tom at the Farm begins with twenty-something Tom, an editor for an ad agency in Montreal, travelling to the rural home of his now dead lover Guillaume Longchamp. The Longchamps own a farm, and after finding the outbuildings deserted, Tom discovers a key to the farmhouse and lets himself in. The building is strangely empty, like the Marie Celeste. Tom falls asleep at the kitchen table but is awoken by Agathe, Guillaume’s mother. Tom explains his presence to Agathe: he is there to attend Guillaume’s funeral. However, Tom conceals from Agathe the fact that he was Guillaume’s lover: Agathe believes that her son was in love with a young woman named Sarah, whose absence at the funeral Agathe curses. Agathe allows Tom to stay the night; he sleeps in Guillaume’s bed. However, he is awoken by Guillaume’s brother Francis. Francis assaults Tom: Francis knows about Tom and Guillaume’s relationship and tells Tom to make sure that he puts on a good performance at the funeral, so that Agathe will not discover that her was gay. After the funeral, Tom invites Sarah, in reality the office’s ‘photocopy girl’, to the farm. Meanwhile, Francis becomes increasingly violent towards Tom, who makes several attempts to leave the farm but, each time, finds himself drawn back to it.  The film’s opening shot is an extreme close-up of the nib of a pen as it is used to write on a napkin (in French): ‘Today is like a part of me has died and I cannot cry. I have forgotten all synonyms for “sadness”. Now, what we need to do, without you, is replace you’. Some of these words Tom later ascribes to Sarah, in conversation with Agathe, displacing them on to the woman whom Agathe believes to be her deceased son’s lover. After the writer of the note (presumably Tom) finishes the last sentence, we hear, offscreen, Tom muttering ‘Fuck this’. From here, Dolan cuts to aerial shots of a car travelling through the rural landscape, signifying the beginning of Tom’s journey, which is accompanied on the soundtrack by an a cappella female vocalist (Kathleen Fortin) singing ‘Les Moulins de Mon Coeur’, the French version of ‘Windmills of Your Mind’. Meanwhile, Tom drives (and chain smokes) his way to the Longchamp’s farm. The film’s opening shot is an extreme close-up of the nib of a pen as it is used to write on a napkin (in French): ‘Today is like a part of me has died and I cannot cry. I have forgotten all synonyms for “sadness”. Now, what we need to do, without you, is replace you’. Some of these words Tom later ascribes to Sarah, in conversation with Agathe, displacing them on to the woman whom Agathe believes to be her deceased son’s lover. After the writer of the note (presumably Tom) finishes the last sentence, we hear, offscreen, Tom muttering ‘Fuck this’. From here, Dolan cuts to aerial shots of a car travelling through the rural landscape, signifying the beginning of Tom’s journey, which is accompanied on the soundtrack by an a cappella female vocalist (Kathleen Fortin) singing ‘Les Moulins de Mon Coeur’, the French version of ‘Windmills of Your Mind’. Meanwhile, Tom drives (and chain smokes) his way to the Longchamp’s farm.

There, he must deal with Guillaume’s family. Agathe is unaware that her son is gay, and Francis is (outwardly) a homophobe: Tom’s first meeting with Francis occurs when Francis attacks Tom whilst he is sleeping in Guillaume’s bed. Holding his hand over Tom’s mouth, silencing him, Francis mutters, ‘I thought you’d be stopping by. I fucking knew it. I don’t know ya but I knew. Shut the hell up. You don’t tell my mother nothin’. She’s sad enough already. She don’t need to know nothing more’. Conversing with Tom, Agathe notes how little she knows about her son’s life in the city: ‘No friends called’, she tells Tom, ‘Figured he didn’t have any. Smart guy like him. Bet they all envied him’. Tom has promised to say something at the funeral (perhaps derived from the eulogy penned on the napkin in the opening sequence), and Francis insists that he ‘spit out some pretty words’ in memory of Guillaume. However, Tom backs out at the last minute, much to the chagrin of Francis. Nevertheless, Agathe supports Tom in this: as he visibly withdraws from the invitation to speak at the funeral, Agathe clasps his hand in hers. This makes Francis even more furious.  The funeral itself is depicted in a fascinating sequence and is introduced through a series of almost still-frame portraits of the attendees. Composed with the subject in the centre of the frame, these shots recall the Carl Dreyer-esque wordless portraits of proletarian faces that we see in the work of filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Pasolini (Accattone, 1961) and Werner Herzog (Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes, 1972). Here, these shots are underscored by tense music, as the priest talks. The priest speaks of the paradise of the afterlife but angers Francis by referring to Guillaume as ‘Guy’ (it seems that Tom also addressed Guillaume by this more informal moniker too). Francis sharply corrects him, in front of the other attendees. When Tom quietly backs out of speaking about Guillaume, Guillaume’s favourite song is played on a CD. As Tom listens to it, Dolan cuts to an enigmatic analepsis/flashback: Tom remembers singing the song in a karaoke bar, in very different circumstances. The juxtaposition of the solemnity of the funeral and the (seemingly drunken) joy and of the karaoke bar is jarring. Later, Tom witnesses Francis and another man intimidating a young man who arrives at the funeral, forcing the young man to return home. Shortly after this, when Tom visits the lavatory, he is assaulted by Francis. Francis holds Tom closely (it seems unclear as to whether Francis wants to hit Tom or kiss him), telling Tom to ‘talk about Sarah. Sarah’s my brother’s girl. Well, in my mom’s mind she is’. The funeral itself is depicted in a fascinating sequence and is introduced through a series of almost still-frame portraits of the attendees. Composed with the subject in the centre of the frame, these shots recall the Carl Dreyer-esque wordless portraits of proletarian faces that we see in the work of filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Pasolini (Accattone, 1961) and Werner Herzog (Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes, 1972). Here, these shots are underscored by tense music, as the priest talks. The priest speaks of the paradise of the afterlife but angers Francis by referring to Guillaume as ‘Guy’ (it seems that Tom also addressed Guillaume by this more informal moniker too). Francis sharply corrects him, in front of the other attendees. When Tom quietly backs out of speaking about Guillaume, Guillaume’s favourite song is played on a CD. As Tom listens to it, Dolan cuts to an enigmatic analepsis/flashback: Tom remembers singing the song in a karaoke bar, in very different circumstances. The juxtaposition of the solemnity of the funeral and the (seemingly drunken) joy and of the karaoke bar is jarring. Later, Tom witnesses Francis and another man intimidating a young man who arrives at the funeral, forcing the young man to return home. Shortly after this, when Tom visits the lavatory, he is assaulted by Francis. Francis holds Tom closely (it seems unclear as to whether Francis wants to hit Tom or kiss him), telling Tom to ‘talk about Sarah. Sarah’s my brother’s girl. Well, in my mom’s mind she is’.

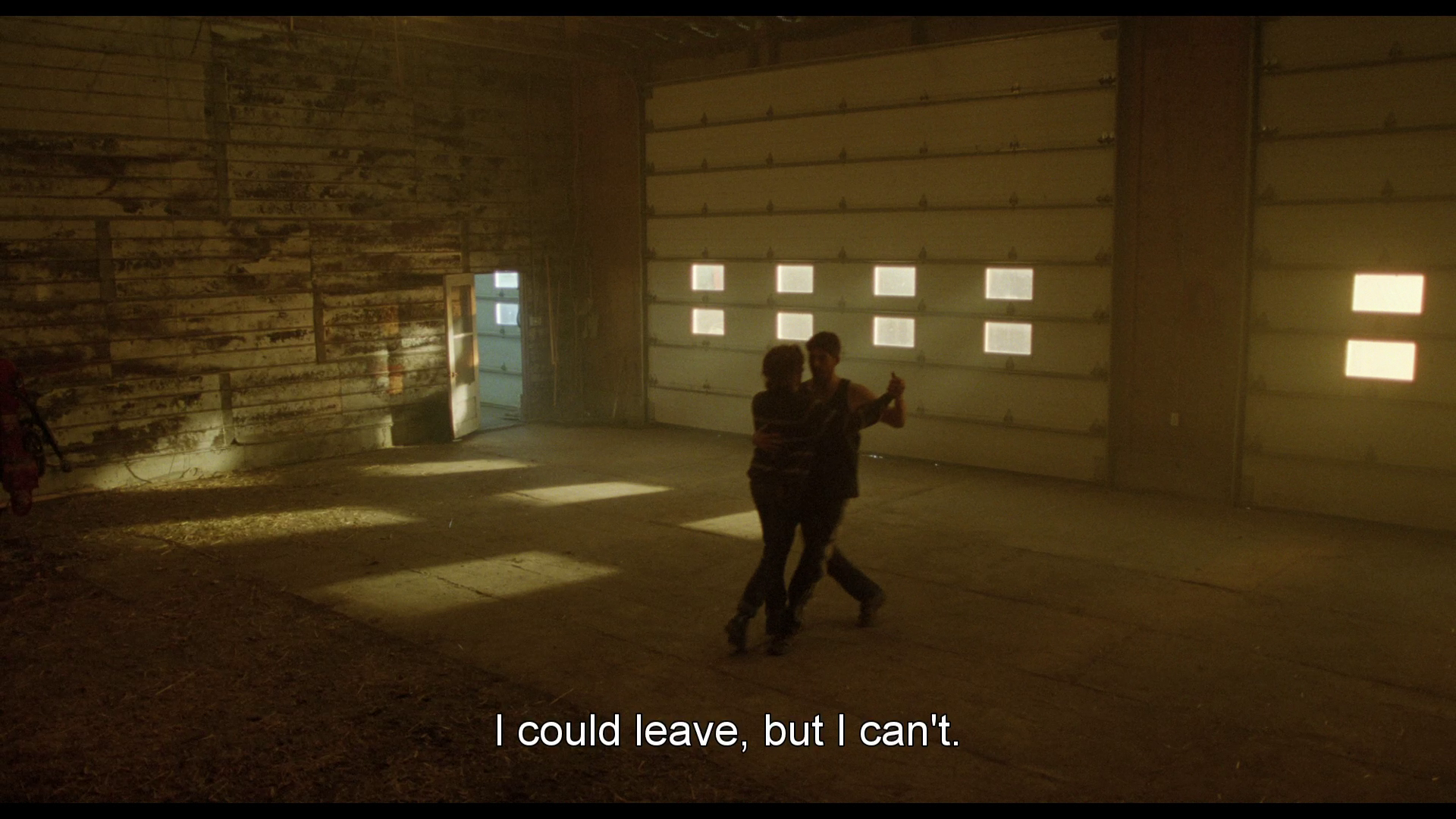

After the funeral, Tom follows the Longchamps’ car back to the farm but at the last minute takes a different turning and drives away, shouting ‘Fuck you! Fucking redneck!’ However, he turns back and returns to the farm. This pattern is repeated several times throughout the film, as Tom is presented with opportunities to escape from the farm but decides to return to it and stay with Agathe and Francis. Meanwhile, Francis’ attacks on Tom (the motivation for which remains ambiguous: there’s a suggestion that these homophobic assaults are motivated by Francis’ own repressed sexuality) become increasingly violent, and as both Francis and Agathe come to see Tom as a substitute for the absent Guillaume, the film also suggests that Francis directed a similar pattern of violence towards his brother.  Gradually, Tom seems to replace Guillaume in the minds of both Agathe and Francis. Agathe allows Tom to sleep in Guillaume’s bed, and they quickly bond, Agathe treating Tom as if he were a son. Tom is also linked to Guillaume by their shared cologne, something which Agathe notices. Meanwhile, Francis enlists Tom’s help in running the farm, involving Tom in milking the cows and also, later, birthing a calf – which becomes Tom’s calf, named ‘Bitch Ass’. During one sequence, Tom is presented with the opportunity to return home, but Francis pleads with him: ‘I know you like me. Don’t go’. He bullies Tom like an elder brother, cajoling him into taking a hit of cocaine despite Tom’s protests that he suffers from tachycardia. Towards the climax of the film, as Tom makes another attempt to leave, Francis pleads with him to stay, using the rhetoric of a man caught abusing his spouse: ‘Tom, don’t you fucking do this to me [….] I fucking need you here [….] I’m trying to be a better person, okay?’ Tom seems confused by Francis’ behaviour: does Francis see Tom as an enemy, a surrogate brother, or a lover? Or does he see Tom as all three of these at the same time? As the film progresses, it is revealed that Guillaume and Francis used to practise the tango together, and in one sequence, after tending to the cattle, Francis invites Tom into the barn where he plays a CD and invites Tom to dance the tango with him. After this, Tom tries to leave but discovers his car has been parked in the garage and the wheels have been stripped from it. Gradually, Tom seems to replace Guillaume in the minds of both Agathe and Francis. Agathe allows Tom to sleep in Guillaume’s bed, and they quickly bond, Agathe treating Tom as if he were a son. Tom is also linked to Guillaume by their shared cologne, something which Agathe notices. Meanwhile, Francis enlists Tom’s help in running the farm, involving Tom in milking the cows and also, later, birthing a calf – which becomes Tom’s calf, named ‘Bitch Ass’. During one sequence, Tom is presented with the opportunity to return home, but Francis pleads with him: ‘I know you like me. Don’t go’. He bullies Tom like an elder brother, cajoling him into taking a hit of cocaine despite Tom’s protests that he suffers from tachycardia. Towards the climax of the film, as Tom makes another attempt to leave, Francis pleads with him to stay, using the rhetoric of a man caught abusing his spouse: ‘Tom, don’t you fucking do this to me [….] I fucking need you here [….] I’m trying to be a better person, okay?’ Tom seems confused by Francis’ behaviour: does Francis see Tom as an enemy, a surrogate brother, or a lover? Or does he see Tom as all three of these at the same time? As the film progresses, it is revealed that Guillaume and Francis used to practise the tango together, and in one sequence, after tending to the cattle, Francis invites Tom into the barn where he plays a CD and invites Tom to dance the tango with him. After this, Tom tries to leave but discovers his car has been parked in the garage and the wheels have been stripped from it.

Meanwhile, as the film progresses Tom seems to develop an increasingly self-destructive streak, blaming himself for Guillaume’s death (the cause of which is never revealed to us), which leads him to accept Francis’ attacks upon him – in something resembling Stockholm Syndrome. Tom’s attitude towards himself becomes increasingly negative: at one point, he tells Agathe that he has spoken with Sarah via telephone. Agathe has protested that ‘That whore [Sarah] should have been here’. Tom relays an imaginary conversation with Sarah to Agathe, using this to explore and express his own feelings about himself in the wake of Guillaume’s death: Tom tells Agathe that Sarah felt she was ‘worthless’ and ‘useless on this Earth, and if [she] couldn’t stop him [Guillaume] from dying, crying’s an even greater waste of time’. Tom continues, speaking of Guillaume’s love affair with Sarah (in reality, Guy’s love affair with Tom): ‘She said… she wished she’d met you. But for him [Guy], love was between two people. No friends, no family, no intruders [….] And… she said he was her first real love’. Then, Tom says, Sarah said ‘I hate myself. I’ll do everything [possible] to set things straight’. Again, Tom is using ‘Sarah’ to express his emotional response to Guillaume’s death and his feelings towards himself. Shortly after, away from Agathe, Francis reveals to Tom that he carries with him a photograph of Guillaume kissing Sarah, who in reality is the office’s ‘photocopy girl’. ‘You carry that around like a trophy’, Tom observes: Francis is desperate for his brother to be seen as straight. ‘Why would you lie to your mother if you love her?’, Tom asks.  This question provokes a brutal response in Francis, who chases Tom through a cornfield and, catching up with him, chokes Tom until he loses consciousness. Francis angrily tells Tom, ‘Don’t tell me what my game is and how to love my mom, okay?’ As Francis is choking Tom, the screen ratio gradually morphs from 1.85:1 to 2.35:1, becoming smaller along its vertical axis. (Dolan has experimented with aspect ratios elsewhere: Laurence Anyways was shot in the ‘quaint’ 1.37:1, and his most recent film Mommy is shot in a square 1:1 ratio.) It’s a dizzying technique which suggests that something particularly nasty is about to happen, and it expresses Tom’s gradual lapse into unconsciousness in a very direct visual manner. This sequence of events (and the change in aspect ratio) is mirrored later in the film, when Francis once again chokes Tom after they both get drunk and it seems that Tom and Francis might be sharing a moment of emotional intimacy that may lead to physical intimacy. As Francis and Tom stand close to one another, Francis again reaches out and throttles Tom. This time, Tom taunts Francis (‘Is that all you got? Harder’). After this, Tom admits to Francis that he reminds Tom of Guillaume: ‘You smell like him’, Tom says, ‘And the voice too. Same fucking voice’. This question provokes a brutal response in Francis, who chases Tom through a cornfield and, catching up with him, chokes Tom until he loses consciousness. Francis angrily tells Tom, ‘Don’t tell me what my game is and how to love my mom, okay?’ As Francis is choking Tom, the screen ratio gradually morphs from 1.85:1 to 2.35:1, becoming smaller along its vertical axis. (Dolan has experimented with aspect ratios elsewhere: Laurence Anyways was shot in the ‘quaint’ 1.37:1, and his most recent film Mommy is shot in a square 1:1 ratio.) It’s a dizzying technique which suggests that something particularly nasty is about to happen, and it expresses Tom’s gradual lapse into unconsciousness in a very direct visual manner. This sequence of events (and the change in aspect ratio) is mirrored later in the film, when Francis once again chokes Tom after they both get drunk and it seems that Tom and Francis might be sharing a moment of emotional intimacy that may lead to physical intimacy. As Francis and Tom stand close to one another, Francis again reaches out and throttles Tom. This time, Tom taunts Francis (‘Is that all you got? Harder’). After this, Tom admits to Francis that he reminds Tom of Guillaume: ‘You smell like him’, Tom says, ‘And the voice too. Same fucking voice’.

Francis’ violence isn’t directed solely against Tom. Part way through the film, Tom invites Sarah to come to the farm, as part of the charade to prove to Agathe that Guillaume was straight. Upon Sarah’s arrival, Francis assaults her and tells her to put on a good show for Agathe. However, Sarah stands up for herself, slapping Francis. Francis’ attitude towards her changes suddenly, the violence provoking desire: ‘Fuck, you’re a babe’, he asserts, ‘I’d fuck you’. Sarah offers Tom the chance to leave the farm: she will take him back to Montreal. However, Tom surprisingly refuses, insisting that he must apologise for Francis’ behaviour. ‘I don’t know what he did to you but I apologise on his behalf’, Tom says, ‘That’s the way he [Francis] is. Can’t change him’. Sarah notices that Tom has been subjected to physical abuse: he is covered in bruises, and his ‘neck is fucking black’. However, Tom insists that he can’t leave the farm: ‘He’ll [Francis will] have to sell if I leave. You’ve got no idea how much work 48 cows is. It’s a big job. Eventually, he’ll institutionalise his mom too. He’ll end up alone here. Meanwhile, what use am I? I’m worth shit’. ‘They’re like family, Sarah’, Tom insists. ‘Look around this place, it’s… it’s real’, Tom adds, ‘It’s all so real. A cow gives birth, there’s blood in the hay. A dog barks, you hear it’.  Later, Tom visits a bar called ‘The Real Thing’, where he acquires a dose of a different kind of reality about Francis’ history of violence. In the bar, Tom discusses the Longchamp family with the bartender, who reluctantly agrees to talk about the mysterious event in Francis’ past which several of the townsfolk have already alluded to, obliquely, in conversation with Tom. Nine years earlier, the bartender tells Tom, Francis and Guillaume visited ‘The Real Thing’ and danced the tango together, ‘like pros. Showing off’. However, when Guillaume danced with another young man, Francis exploded and assaulted the other patron: Francis, in the words of the bartender, ‘[p]ut his hands in and tore his mouth apart […. f]rom ear to throat’. The victim of the attack, Tom is told, lives in a nearby village and is unmistakeable owing to the scarring on his face. At the climax of the film, after Tom has finally managed to break free from the hold that the farm has over him, he stops by a petrol station on the way to Montreal and glimpses the victim of this attack working as a mechanic in the workshop at the rear of the building, his face distorted by scarring that resembles a ‘Glasgow smile’. Later, Tom visits a bar called ‘The Real Thing’, where he acquires a dose of a different kind of reality about Francis’ history of violence. In the bar, Tom discusses the Longchamp family with the bartender, who reluctantly agrees to talk about the mysterious event in Francis’ past which several of the townsfolk have already alluded to, obliquely, in conversation with Tom. Nine years earlier, the bartender tells Tom, Francis and Guillaume visited ‘The Real Thing’ and danced the tango together, ‘like pros. Showing off’. However, when Guillaume danced with another young man, Francis exploded and assaulted the other patron: Francis, in the words of the bartender, ‘[p]ut his hands in and tore his mouth apart […. f]rom ear to throat’. The victim of the attack, Tom is told, lives in a nearby village and is unmistakeable owing to the scarring on his face. At the climax of the film, after Tom has finally managed to break free from the hold that the farm has over him, he stops by a petrol station on the way to Montreal and glimpses the victim of this attack working as a mechanic in the workshop at the rear of the building, his face distorted by scarring that resembles a ‘Glasgow smile’.

When Tom finally returns in Montreal, at night, he gazes at the inhabitants of the city as if they were aliens. Dolan repeats a visual motif that has appeared throughout the film: a side-on close-up of Tom’s hands on the steering wheel of the car, his grip tightening and then relaxing. The shot, accompanied on the soundtrack by the disquieting creak of leather, is suggestive of anxiety - and is reminiscent of the shots of the nameless protagonist of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2012)’s obsessive, ritualistic habit of checking his steering wheel and flexing his hands in his leather gloves. The suggestion is that Tom’s experiences at the farm, disabling and frightening though they may be, will forever impact on his worldview and alienate him from the life to which he was previously accustomed. The farm, despite the traumas associated, is more ‘real’ than Tom’s life in the city; this fact will forever haunt Tom, Dolan seems to suggest.   The two sequences in which Tom finds himself in the empty farmhouse are eerie and bring to mind Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1972), in which whilst visiting Toledo American tourist Lisa (Elke Sommer) is whisked away to a mansion populated by an eccentric family of aristocrats. Towards the end of the film, Lisa awakens in the mansion, which she discovers is really in a state of ruin and overgrown with vegetation. Her experiences there are thus ambiguous: has she been bewitched by the place and simply dreamt them? Similarly, in Tom at the Farm, when Tom first arrives at the Longchamp farm, he finds it eerily quiet. He explores the farm buildings but finds no-one present. Discovering a key to the house, he enters the building and finds the house deserted, like the Marie Celeste: there are signifiers that the house is inhabited (plates containing the remnants of meals, etc) but the absence of any human figure is unsettling, a point that is underscored by the tracking shots which follow Tom and restrict our perspective, and the tense Bernard Herrman-esque score that rumbles on the soundtrack. The two sequences in which Tom finds himself in the empty farmhouse are eerie and bring to mind Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1972), in which whilst visiting Toledo American tourist Lisa (Elke Sommer) is whisked away to a mansion populated by an eccentric family of aristocrats. Towards the end of the film, Lisa awakens in the mansion, which she discovers is really in a state of ruin and overgrown with vegetation. Her experiences there are thus ambiguous: has she been bewitched by the place and simply dreamt them? Similarly, in Tom at the Farm, when Tom first arrives at the Longchamp farm, he finds it eerily quiet. He explores the farm buildings but finds no-one present. Discovering a key to the house, he enters the building and finds the house deserted, like the Marie Celeste: there are signifiers that the house is inhabited (plates containing the remnants of meals, etc) but the absence of any human figure is unsettling, a point that is underscored by the tracking shots which follow Tom and restrict our perspective, and the tense Bernard Herrman-esque score that rumbles on the soundtrack.

The shot of the kitchen table at which, upon discovering the farmhouse is empty, Tom sits and waits, repeated throughout the film, is composed in a self-conscious style, with a frame within the film frame: the table is contained within a doorway through which the camera shoots. Sitting at the table, Tom falls asleep, like Goldilocks in the home of the three bears. He is awoken by Agathe who, rather than being angry, offers Tom hospitality. A similar series of events recurs at the end of the film when Tom awakes in Guillaume’s bed to find the house, once again, is strangely deserted, with no sign of the presence of either Agathe or Francis – almost as if Agathe or Francis, like the aristocrats that ‘haunt’ the mansion in Bava’s film, are spectral figures or figments of Tom’s imagination. This moment offers Tom the opportunity to break the spell that the farm (and/or its inhabitants) has cast over him, and he packs his suitcase and flees from the place. The film is uncut and runs for 103:00 mins.

Video

The film, taking up approximately 17Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc, is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio (with some sequences, as noted above, presented in 2.35:1). Much of the film is shot with a very muted colour palette, but despite this colour consistency is strong throughout. Contrast levels are good too (which is helpful, as a good portion of the film is shot in low light situations), and throughout the film has a very organic look. This is a pleasing presentation, despite the small file size.

Audio

Two audio options are present: a 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio track and an LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both of these are fine, but given Dolan’s expressive use of music and the subtle sound design of the film (the haunting use of surround effects when Tom explores the deserted Longchamp farm, for example), the 5.1 track is preferable. The dialogue contains a mixture of Québécois French and English. The cultural differences between city boy Tom and the Longchamps are partly communicate through the dialogue, in terms of the juxtaposition of Tom’s accent with the more rustic speech patterns of the rural family. This is expressed in the English subtitles through the use of idiomatic English (with lots of ‘y’knows’, ‘yas’ and ‘nothin’’s) in the subtitling of the dialogue of Francis and Agathe. The English subtitles on this disc are sadly not optional.

Extras

The sole extra here is the film’s trailer (1:56).

Overall

The set-up of Tom at the Farm is familiar: it has superficial similarities with, say, John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), in which Spencer Tracy arrives in Black Rock to pay tribute to a war comrade who has recently passed away; or perhaps even First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982), in which the nomadic John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) arrives at the home of a fellow Vietnam veteran to find that he has recently passed on owing to exposure to Agent Orange, provoking an existential crisis in Rambo that leads to the rampage of violence for which the film is most famous. Like those films, Tom at the Farm focuses on alienation and repression: Tom’s repression of his relationship with Guy causes such self-loathing that Tom willingly submits to the violence directed towards him by Francis. However, as Tom discovers, the rural life of the Longchamps is more ‘real’ than his life in Montreal: the film’s closing sequence suggests Tom’s subsequent life will be haunted by this realisation. The set-up of Tom at the Farm is familiar: it has superficial similarities with, say, John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), in which Spencer Tracy arrives in Black Rock to pay tribute to a war comrade who has recently passed away; or perhaps even First Blood (Ted Kotcheff, 1982), in which the nomadic John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) arrives at the home of a fellow Vietnam veteran to find that he has recently passed on owing to exposure to Agent Orange, provoking an existential crisis in Rambo that leads to the rampage of violence for which the film is most famous. Like those films, Tom at the Farm focuses on alienation and repression: Tom’s repression of his relationship with Guy causes such self-loathing that Tom willingly submits to the violence directed towards him by Francis. However, as Tom discovers, the rural life of the Longchamps is more ‘real’ than his life in Montreal: the film’s closing sequence suggests Tom’s subsequent life will be haunted by this realisation.

Tom at the Farm also invites parallels with icy French 21st Century Hitchcockian thrillers such as Harry, un ami qui vous veut du bien (Harry, He’s Here to Help / With a Friend Like Harry; Dominik Moll, 2000) and Lemming (Dominik Moll, 2005), especially in its exploration of identity: during his stay at the farm, Tom takes on some of the qualities of Guy, and to some extent both Agathe and Francis treat Tom as if he were their deceased son/brother. (The insular rural setting of Tom at the Farm also recalls Harry, He’s Here to Help.) However, the film is resolutely Dolan’s. With I Killed My Mother, Heartbeats, Laurence Anyways and now Tom at the Farm (and Dolan’s most recent picture, Mommy), Dolan has carved a niche for himself: despite their director’s youth, these films have a strong connection with one another, both in terms of theme (their focus on alienation and the repression of an aspect of one’s identity) and their presentation (visual motifs including languorous tracking shots, the use of secondary frames within the film frame). The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is pleasing, though the file size is quite small and a stronger encode may have provided a slightly more robust presentation. Given the enigmatic nature of the film, the inclusion of some more thorough contextual material (in the form of interviews, etc) would have been more than welcome. Nevertheless, the film itself is very strong and shows the development of Dolan’s work as an auteur – though fans of Dolan’s previous work will note that Tom at the Farm is far less playful than the films that preceded it in Dolan’s filmography. With any luck, Dolan’s recent Mommy will hit screens in Britain sooner rather than later. This review has been kindly sponsored by Network. Please visit their website: www.networkonair.com

|

|||||

|