|

|

Beast (The) AKA La Bête AKA Death's Ecstacy AKA The Beast in Heat (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st August 2014). |

|

The Film

La bête / The Beast (Walerian Borowczyk, 1975)  This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release. This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release.

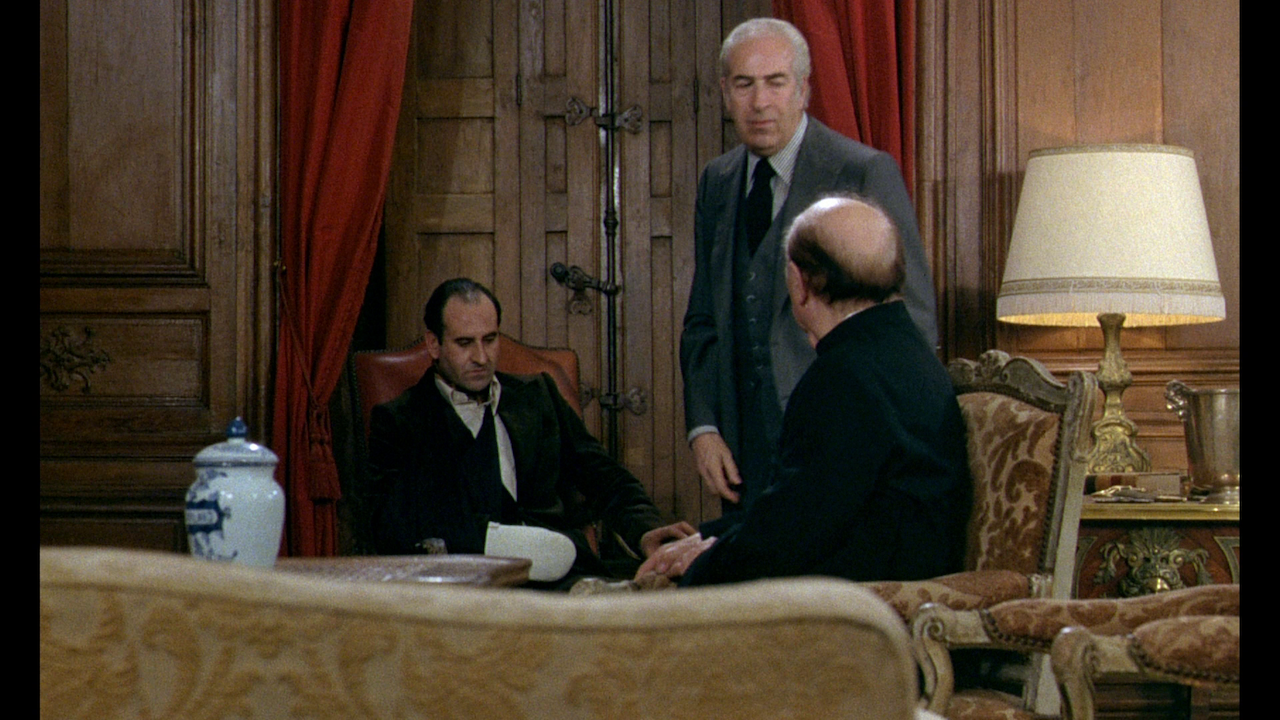

NB. Faced with the wondrous (mountainous?) pleasures of Arrow’s new set of Borowczyk releases, it’s difficult to know where to start. I decided to begin with La bête, as it is a film that, despite admiring greatly, I haven’t seen in over a decade. Links to reviews of the other Borowczyk discs will be added to this review as they go ‘live’ over the coming week. Our review of Blanche (1971) can be found here. Our review of Goto, Isle of Love (1968) can be found here. Our review of Immoral Tales (1974) can be found here. - Our review of Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation can be found here. After Blanche (1972), Borowczyk’s work became increasingly difficult to pigeon-hole, and Borowczyk seemed to actively fight to defy easy categorisation of his work. From Immoral Tales (1974) onwards, Borowczyk came to be associated, in the eyes of many viewers and critics, with erotica and soft-core pornography. La bête (The Beast, 1975) marked something of a turning point in terms of perceptions of Borowczyk’s work, particularly in the UK, owing to its protracted battle with the BBFC and the involvement of the Director of Public Prosecutions; after La bête, Borowczyk was, in Derek Malcolm’s words, ‘regarded in this country [the UK] as a pseudo-cultured pornographer’ (Malcolm, 2000: np). Daniel Bird has cited La bête as the film that ‘would prove to be one of the most controversial, divisive and discussed works in cinema history’, which ‘all but destroy[ed] any prospects of mainstream acceptance for the challenging auteur, and finally consign[ed] him to, at best, arthouse acclaim’ (2011: 161). Borowczyk was certainly a filmmaker fascinated with the layered complexities of human sexuality, but his films were (and remain) pictures that use the form for more than mere titillation. An abiding focus within his films is the issue of conflicting mores towards sexuality, and an overriding theme is repression – which manifests itself in different forms throughout his body of work. One way in which repression manifests itself is through the realm of dreams, and this arguably forms the key focus of La bête.  Mathurin (Pierre Benedetti), a horse breeder and the son of a Marquis, Pierre de l’Esperance (Guy Tréjan), is set to marry Lucy Broadhurst (Lisbeth Hummel). Mathurin and Lucy have never met, but they have corresponded via letter – or rather, Lucy has corresponded with Pierre, who has written letters to Lucy on the behalf of his crude, animalistic son. The marriage is one of convenience for Pierre, as Lucy’s family is wealthy and the fortunes of Pierre’s family are falling behind them. However, Lucy’s marriage must be blessed by the Cardinal Joseph de Balo (Jean Martinelli). The Cardinal will not speak with Pierre or Mathurin, believing them to be ‘pagans’: he will only communicate with Pierre through the Cardinal’s brother (and Pierre’s uncle), Duc Rammondelo de Balo (Marcel Dalio). Mathurin (Pierre Benedetti), a horse breeder and the son of a Marquis, Pierre de l’Esperance (Guy Tréjan), is set to marry Lucy Broadhurst (Lisbeth Hummel). Mathurin and Lucy have never met, but they have corresponded via letter – or rather, Lucy has corresponded with Pierre, who has written letters to Lucy on the behalf of his crude, animalistic son. The marriage is one of convenience for Pierre, as Lucy’s family is wealthy and the fortunes of Pierre’s family are falling behind them. However, Lucy’s marriage must be blessed by the Cardinal Joseph de Balo (Jean Martinelli). The Cardinal will not speak with Pierre or Mathurin, believing them to be ‘pagans’: he will only communicate with Pierre through the Cardinal’s brother (and Pierre’s uncle), Duc Rammondelo de Balo (Marcel Dalio).

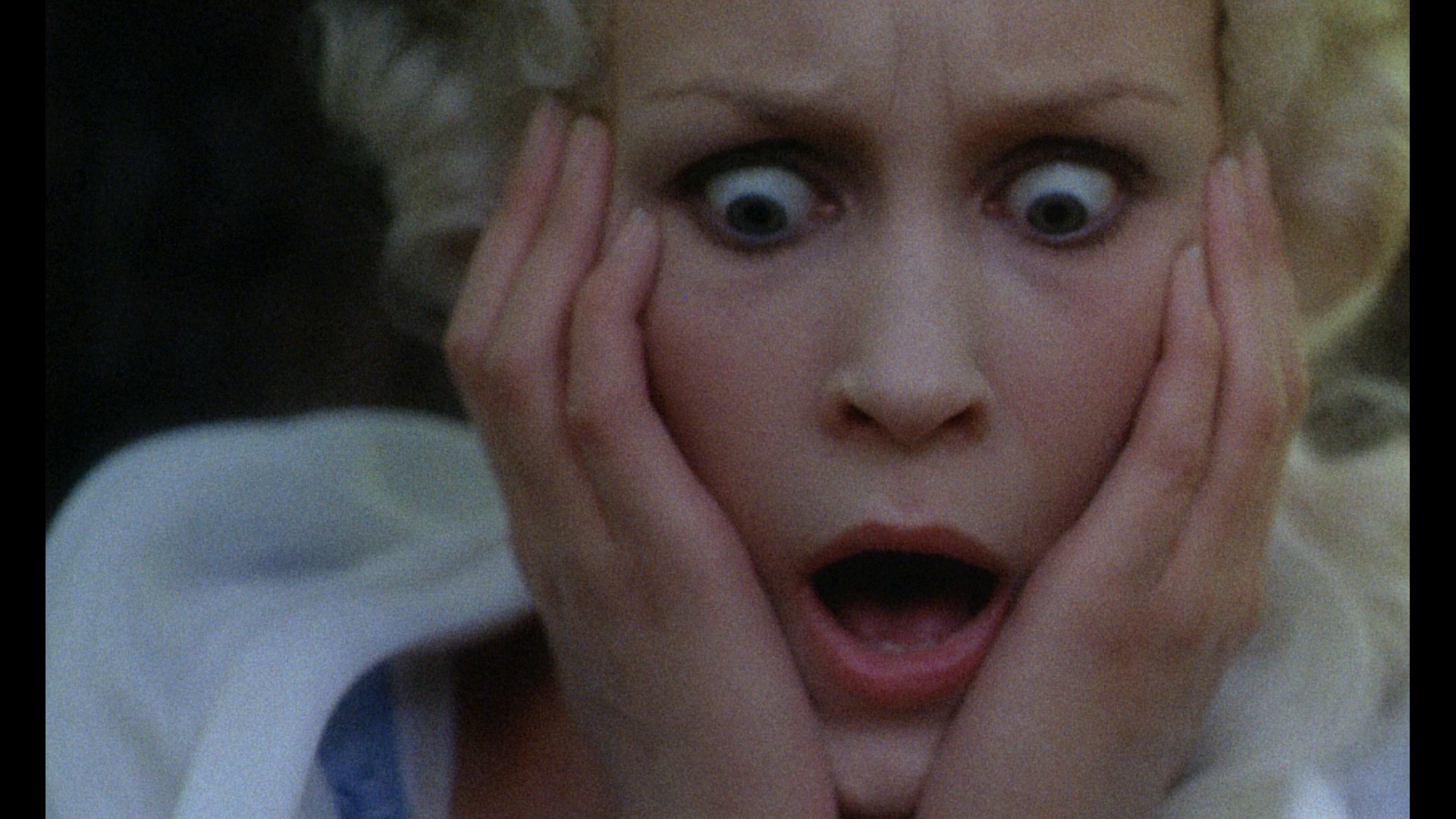

To gain the blessing of the Cardinal, Mathurin must first be baptised, according to the wishes of Lucy’s recently deceased father, Philip Andrew Broadhurst. To do this, Pierre enlists the help of a priest (Roland Armontel), who arrives at the chateau with two young boys, Theodore (Anna Baldaccini) and Modeste (Thierry Bourbon). The priest’s interest in the two boys appears to be less than innocent, however. Pierre persuades the priest to allow Pierre to conduct the baptism himself, in return for a promise to buy a new bell for the church. Rammondelo is angered by the plan to marry Mathurin and Lucy: Mathurin cares for Rammondelo, and Rammondelo does not wish for the young man to leave him. Pierre blackmails Rammondelo into contacting the Cardinal by threatening to reveal a secret that Rammondelo has kept for forty-five years: Rammondelo killed his wife by poisoning her. Meanwhile, Lucy and her aunt Virginia (Elizabeth Kaza) arrive at the chateau. Lucy is sexually excited at the prospect of her impending marriage to the animalistic Mathurin, despite having never met him before. She questions Rammondelo over the ‘rumours’ about the household; Rammondelo tells her about his ancestor Romilda de l’Esperance (Sirpa Lane), who 200 years earlier had an encounter with a mysterious beast in the woodlands that surround the chateau. Over dinner, Mathurin displays his uncouth manners. Virginia threatens to leave with Lucy, but Pierre persuades her to stay. Laden with wine, the occupants of the chateau fall asleep. Pierre sends Lucy a love note (ostensibly from his son, Mathurin) and a red rose. Then, after overhearing Rammondelo speaking with the Cardinal on the telephone, trying to persuade the Cardinal not to bless the wedding, Pierre interrupts the telephone call and kills Rammondelo by slashing his throat. In an extended sequence, whilst the other inhabitants of the chateau sleep, Lucy retires to her bedroom and masturbates with the rose, fantasising about Romilda’s encounter with the beast in the woods. Following a lamb into the woodlands surrounding the chateau, Romilda encounters the beast as it devours the innocent creature. The beast pursues Romilda and rapes her; but Romilda gradually seems to take pleasure in the assault.  Lucy’s fantasy comes to an end. She sneaks into Mathurin’s bedroom and attempts to rouse him from sleep and seduce him. However, she finds Mathurin dead on the floor next to his bed. Lucy screams, waking the whole house. Mathurin’s body is laid out. Virginia secretly examines the body of the dead man, discovering that his body is matted with hair, the cast on his arm (supposedly there owing to a riding accident) conceals a beast’s arm, and to top it all off, Mathurin has a tail. Taking Lucy, Virginia flees from the chateau, just as the Cardinal arrives. Lucy and Virginia return home in their chauffeur-driven car. At the chateau, the Cardinal denounces bestiality as ‘the most odious crime because it debases man, made in the image of God’. Meanwhile, in the car Lucy falls asleep and dreams once again of Romilda. The beast expires, apparently from ecstasy; Romilda covers the body with leaves, an act that seems to symbolise repression, and returns to the chateau. Lucy’s fantasy comes to an end. She sneaks into Mathurin’s bedroom and attempts to rouse him from sleep and seduce him. However, she finds Mathurin dead on the floor next to his bed. Lucy screams, waking the whole house. Mathurin’s body is laid out. Virginia secretly examines the body of the dead man, discovering that his body is matted with hair, the cast on his arm (supposedly there owing to a riding accident) conceals a beast’s arm, and to top it all off, Mathurin has a tail. Taking Lucy, Virginia flees from the chateau, just as the Cardinal arrives. Lucy and Virginia return home in their chauffeur-driven car. At the chateau, the Cardinal denounces bestiality as ‘the most odious crime because it debases man, made in the image of God’. Meanwhile, in the car Lucy falls asleep and dreams once again of Romilda. The beast expires, apparently from ecstasy; Romilda covers the body with leaves, an act that seems to symbolise repression, and returns to the chateau.

The word ‘nightmare’, which nowadays is most often used to denote an unpleasant dream, originally denoted a visitation, by night, of a ‘mare’ (‘maere’ or ‘moere’, a Germanic word referring to a goblin, incubus or ‘hag’). Preying on its sleeping victim at night, the mare/incubus would produce evil, unpleasant dreams by sitting on the body of the sleeper. The sleeper would be left with profound feelings of unease, anxiety or oppression. The experience of having a ‘night-mare’, or being visited by an incubus, was seen as either being caused by a disease which deceived the senses of the sufferer, or was taken as a ‘real’ experience, often associated with witchcraft. Integral to the experience of the nightmare, therefore, were questions about the relationships that exist between dreams and reality. Nightmares were sometimes cited as incidents of being hag- or witch-ridden, and evidence suggests that as late as 1875 people were accusing others of ‘hag-riding’ – sending the maere/mare or hag to them, to ride them in the night (see Riviere, 2013: 51). The nightmare was associated with ‘the assaults of “lewd” demons’ (Riviere, op cit.: 51). Being ‘hag-ridden’ or ‘witch-ridden’ (ie, having a ‘night-mare’) was seen as suggestive of a sexual assault. In Epotomania; or, A Treatise Discoursing of the Essence, Causes, Symptomes, Prognosticks, and Cure of Love or Erotique Melancholy (1640), James Ferrand noted that suffers of the nightmare believed they had ‘some Divell, or Witch, that would attempt a breach upon their Chastity’ (Ferrand, quoted in ibid.: 56). Nightmares thus had a ‘sexualised aspect’, an ‘erotic feature’ that ‘helps to shed light on premodern sexual fantasies’ (ibid.). A cure for nightmares was often suggested to be ‘moderation of the individual sexual appetites’ (Riviere, op cit.: 52). This would suppress the nightmare, saving the sufferer from the visitation (‘real’ or otherwise) of the hag or maere/mare, thus avoiding the experience of being ‘hag-ridden’. Aside from hags and maeres/mares, victims of the nightmare also gave accounts of being assaulted by demonic beasts (often demonic cats, which were said to steal the breath of the victim, but other creatures too). In other accounts, the incubus (or succubus) took a more human form: Thomas Heywood’s The Hierarchie of the Blessed Angells (1635) outlines an account of the maid of a Scottish family who fell pregnant after, she claimed, being visited repeatedly at night by an incubus in the form of a ‘beautiful young man’ (quoted in ibid.: 55). Females who had been ‘ridden’ in such a way could become pregnant, King James I noted in Daemonologie (1597), but the child ‘was often born a monster’ (Fudge, op cit.: 57). Heywood also discusses the tale of a Parisian nobleman who, during an evening walk through the city, met a beautiful woman who he took home, slept with, and upon waking in the morning discovered in his bed the corpse of a witch who had been recently executed (Heywood, cited in Riviere, op cit.: 55). Nightly visitations by maeres/mares were also blamed for sexually indulgent behaviour, nocturnal emissions, masturbation and sexual dreams. In works such as ‘Bobok’ and ‘The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’, Doestoevsky explores the extent to which the nightmare can reduce words to meaningless, animalistic cries (see Khapaeva, 2012: 174). Nightmares, by their nature, ‘resist articulation’: it’s a trope within fiction revolving around nightmares that the person who experiences a nightmare finds it impossible to express what has happened to them, finding the nature of the nightmare itself to be inexpressible (ibid.). The narrators of H P Lovecraft’s nightmarish fiction, for example, find it impossible to communicate their experiences; language fails them, though they are ‘affected by the urgency to convey the nightmare, the need to share this important internal experience’ (ibid.: 175). In resisting verbalisation and challenging our intellectual ability to express ideas in words, the nightmare represents a ‘paralyzed muteness’ that is revolutionary and challenges our perception of the world; nightmares highlight the ‘contrast between words and feelings’, and therefore often ‘materialize as madness’ (ibid.: 176). For premodern peoples, the distinction between human and animal (and between the reason represented by the former, and the unreason represented by the latter) was often eroded in the realm of sleep and dreams, where a human could perceive themselves as an animal, or may perceive human-like qualities (for example, the ability to speak) in beasts (see Fudge, 2007a: 4). In the same era, human society became increasingly interested in its ability to exert its control and mastery over ‘brute creation’ (ibid.: 7). In 1609, Nicholas Morgan proposed in The Perfection of Horse-manship that human mastery over beasts is emblematised in horse-riding, which ‘replicates that which was held by Adam before the exit from Eden’ (ibid.). Horse-riding thus represents a ‘return to a perfect natural order’, in which human is dominant over beast (ibid.). The act of riding a horse ‘images the control of the human, the obedience of the animal, and - in more literal terms - man on top’ (ibid.). This mastery of ‘brute creation’ is something that is subverted by the nightmare, in which the human is ridden by its opposite, the inhuman. In the nightmare, the human is positioned as the beast; the inhuman is given dominion. Whew. Got that? Glad you’ve stuck with me so far. If you’re familiar with La bête, I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this history lesson. It’s not a huge tangent, I promise.  Revisiting La bête, it’s surprising how much of the film revolves around sleep, nightmares and dream-like states. The film opens with a quote from Voltaire, ‘Troubled dreams are in fact a passing moment of madness’, a statement which echoes some of Khapaeva’s discussion of the ways in which nightmares pose a challenge to our ability to articulate the world, often ‘materializ[ing] as madness’. The titles sequence itself is like the prelude to a nightmare: a black screen, the sound of whinnying and horses’ hooves on cobblestones; the credits play as white text on a black background; the film’s title is presented as blood red text. Finally, the events of the last forty minutes of the film take place as most of the inhabitants of the chateau are asleep. Borowczyk interrupts the sequence depicting Romilda’s experiences with the beast in the woods with shots of the people in the chateau sleeping (which also functions as a juxtaposition of the modern with the premodern). Lucy’s vision of Romilda, and her experiences with the beast in the woodlands surrounding the chateau, are framed ambiguously: they are part-analepsis/flashback to the past of Pierre’s family, part dream (which begins as a nightmare), and part erotic reverie. Revisiting La bête, it’s surprising how much of the film revolves around sleep, nightmares and dream-like states. The film opens with a quote from Voltaire, ‘Troubled dreams are in fact a passing moment of madness’, a statement which echoes some of Khapaeva’s discussion of the ways in which nightmares pose a challenge to our ability to articulate the world, often ‘materializ[ing] as madness’. The titles sequence itself is like the prelude to a nightmare: a black screen, the sound of whinnying and horses’ hooves on cobblestones; the credits play as white text on a black background; the film’s title is presented as blood red text. Finally, the events of the last forty minutes of the film take place as most of the inhabitants of the chateau are asleep. Borowczyk interrupts the sequence depicting Romilda’s experiences with the beast in the woods with shots of the people in the chateau sleeping (which also functions as a juxtaposition of the modern with the premodern). Lucy’s vision of Romilda, and her experiences with the beast in the woodlands surrounding the chateau, are framed ambiguously: they are part-analepsis/flashback to the past of Pierre’s family, part dream (which begins as a nightmare), and part erotic reverie.

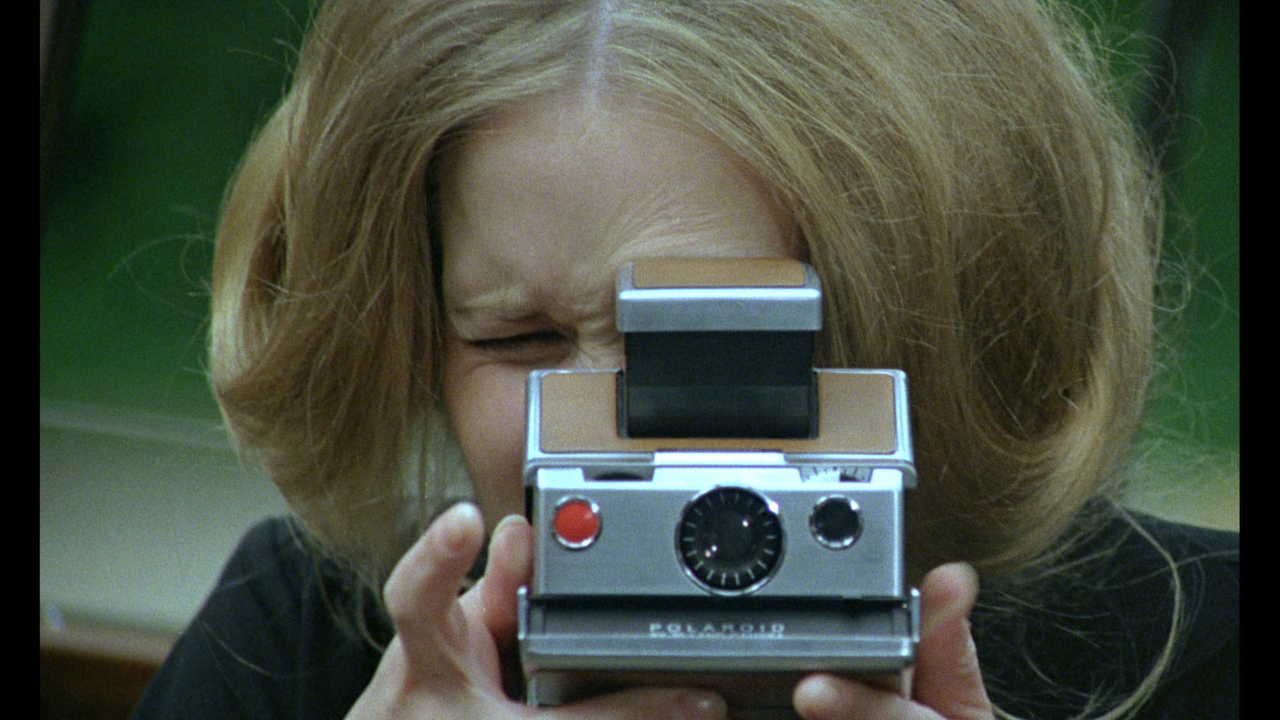

During the sequence in which Lucy first meets Rammondelo, she enquires about the rumours that ‘ghost haunt the castle’. Rammondelo tells her that these are ridiculous, but he shows Lucy the book written by Romilda, in which she describes a creature in the woods (‘I met him and then overcame him’, suggestive of the struggle for control between human and animal). Romilda’s corset, which bears ‘traces of claw marks’, is kept in a glass display cabinet. Lucy picks up a framed piece of text, making an observation about it: ‘What beautiful handwriting’. Holding the frame up, she notices something etched into the rear of it. Blowing dust from the surface of the rear of the frame, believing it to contain an autograph, Lucy discovers upon it a sketch of a dog fucking a woman. Shortly after, exploring the house by herself, Lucy finds an edition of Voltaire’s 1878 La pucelle d’Orleans, poeme heroi-comique en dix-huit chants. The book opens to a page containing an illustration which is not unlike Henry Fuseli’s famous 1781 The Nightmare, which depicts an incidence of ‘hag-riding’. The illustration in the book depicts what appears to be a bedroom. On the left, a woman covers her eyes with her right hand, her left raised; the gesture suggests horror. In the centre of the image, a winged steed (presumably Joan of Arc’s ‘winged ass’) is mounting (fucking) a man, who is bent forwards on his hands and knees, his head hanging.  Furthermore, Mathurin is a breeder of horses, a profession that symbolises the mastery of nature about which Nicholas Morgan wrote – and which is subverted in the illustration that Lucy finds in the Voltaire book. However, Mathurin displays an uneasy fascination with the sexual habits of his stallions and mares. Interestingly, Lucy also begins to show an interest in this: using her Polaroid camera, when she first arrives at the chateau she takes photographs of the horses as they copulate. Later, these are spread out in front of her, and she begins to caress her body erotically. The cast on Mathurin’s arm, we are told, is there because he suffered an accident whilst riding one of his horses, suggesting a fissure in Mathurin’s ability to master nature (represented through the horses). Tellingly, we are told that Mathurin’s arm was tended to by a vet. However, as Lucy and Virginia discover at the end of the film, the cast is there to obscure Mathurin’s beastly arm and hand: the cast conceals Mathurin’s secret. Furthermore, Mathurin is a breeder of horses, a profession that symbolises the mastery of nature about which Nicholas Morgan wrote – and which is subverted in the illustration that Lucy finds in the Voltaire book. However, Mathurin displays an uneasy fascination with the sexual habits of his stallions and mares. Interestingly, Lucy also begins to show an interest in this: using her Polaroid camera, when she first arrives at the chateau she takes photographs of the horses as they copulate. Later, these are spread out in front of her, and she begins to caress her body erotically. The cast on Mathurin’s arm, we are told, is there because he suffered an accident whilst riding one of his horses, suggesting a fissure in Mathurin’s ability to master nature (represented through the horses). Tellingly, we are told that Mathurin’s arm was tended to by a vet. However, as Lucy and Virginia discover at the end of the film, the cast is there to obscure Mathurin’s beastly arm and hand: the cast conceals Mathurin’s secret.

At the end of the film, once Mathurin’s true nature has been revealed, and after Lucy has had her vision of Romilda being ravished by the beast (thus representing the nightmare’s overturning of the ‘natural order’ which places man ‘on top’ of beast), Virginia and Lucy both find that language escapes them. Lucy is able only to scream, whilst Virginia shouts repeatedly, ‘The beast! The beast!’ The subversion of the ‘natural order’ results in the ‘paralysing muteness’ associated with the nightmare. When Virginia and Lucy flee the chateau, being driven away by their chauffeur, Virginia caresses Lucy’s head as the young woman sleeps. Lucy’s final dream is symbolic of repression, representing the end of the subversive nightmare: she dreams of Romilda covering the body of the dead beast with leaves and returning to the chateau. The sequence implicitly suggests that Virginia is happy for Lucy to suppress the desires that, during her stay in the chateau, bubbled to the surface. The gesture of covering the beast with leaves also seems to suggest a return to the ‘natural order’ that the nightmare/dream/flashback about the beast represents, with man ‘on top’ of nature.  The bloodline of Pierre’s family is the product of the carnal union between Romilda and the beast, two hundred years prior to the era in which the film’s narrative takes place. Like King James I proposed in Daemonologie, the union of such a creature and a human woman would result in a monster: Mathurin’s curious physical defects, we are led to believe, are those of the beast – they are a curse of sorts. The nature of Pierre’s family, and especially Mathurin, is hinted at throughout the film, before it is finally revealed at the end of the picture. When Pierre tells Rammondelo that Mathurin is to be baptised, Rammondelo notes that ‘nothing will change the nature of your son’. Borowczyk reinforces this with shots of Mathurin gazing lewdly (and/or curiously) at the mating rituals of the horses. Later, Mathurin informs Pierre, ‘You can’t change me. I’ll always be Mathurin, father’. The bloodline of Pierre’s family is the product of the carnal union between Romilda and the beast, two hundred years prior to the era in which the film’s narrative takes place. Like King James I proposed in Daemonologie, the union of such a creature and a human woman would result in a monster: Mathurin’s curious physical defects, we are led to believe, are those of the beast – they are a curse of sorts. The nature of Pierre’s family, and especially Mathurin, is hinted at throughout the film, before it is finally revealed at the end of the picture. When Pierre tells Rammondelo that Mathurin is to be baptised, Rammondelo notes that ‘nothing will change the nature of your son’. Borowczyk reinforces this with shots of Mathurin gazing lewdly (and/or curiously) at the mating rituals of the horses. Later, Mathurin informs Pierre, ‘You can’t change me. I’ll always be Mathurin, father’.

Pierre’s daughter Clarisse (Pascale Rivault) is also affected by the fallout from Romilda’s woodland romp with the beast. Clarisse is seemingly unable to control her desire for Ifany (Hassane Fall), Pierre’s black manservant. By juxtaposing shots of Ifany’s penis with that of the stallion, Ifany is outrageously compared visually with the stallion that Mathurin breeds in the opening sequence. Each time Clarisse and Ifany start to make love, they are interrupted by Pierre’s shout of ‘Ifany! Ifany!’, and Ifany is commanded to run another errand whilst the frustrated Clarisse is left to masturbate on the bedpost. The aristocratic characters go to great lengths to establish the difference between human and animal, which as the film progresses becomes gradually eroded. ‘We, frail humans, we are like animals’, the priest tells Pierre during a discussion of human nature: ‘We suffer the laws of nature’. ‘Happily, we have this intelligence, this heavenly gift, which enables us to fight our instincts’, Pierre responds. However, like de Sade (or, to cite a more recent cinematic equivalent, Bunuel), Borowczyk slyly points to the venality of the ruling classes: the aristocrats are descended from a bloodline created by the union of woman and beast, and the priest is revealed to be a pederast. Even Clarisse is affected by this: during her liaisons with Ifany, she irresponsibly hides the young children she is supposed to be caring for, Stephane and Marie, in the wardrobe.  Mathurin and Lucy’s marriage has been facilitated by Pierre as a means of overcoming the downturn in the fortunes of Pierre’s family. Rammondelo, meanwhile, wants the family to die out quietly, referring cynically to Mathurin’s relationship with Lucy as ‘Love by correspondence’. In response to this, Pierre states angrily that ‘He [Mathurin] realised that you want to ruin this house, that your warnings betray your desire to destroy our family’. It’s clear that Pierre has been communicating with Lucy on Mathurin’s behalf: Mathurin is uncouth and seemingly impossible to communicate with. Prior to Lucy’s arrival, Pierre shaves and bathes his son. When Lucy retires to her room, Pierre has his servant Ifany send up a love note from Mathurin (in reality written by Pierre) and a red rose. Reading the note provokes desire in the sexually repressed Lucy, and a couple of times she sneaks into Mathurin’s bedroom and tries to rouse him from sleep, one time even grabbing at his penis. However, the sleeping Mathurin simply grunts and shrugs her away, turning back towards the wall. Frustrated once again, Lucy returns to her bedroom and, dreaming of Romilda’s experience with the beast, masturbates with the flower that, she believes, her lover sent her. Lucy’s desire is thus predicated on a lie, a fabrication concocted by Pierre. Mathurin and Lucy’s marriage has been facilitated by Pierre as a means of overcoming the downturn in the fortunes of Pierre’s family. Rammondelo, meanwhile, wants the family to die out quietly, referring cynically to Mathurin’s relationship with Lucy as ‘Love by correspondence’. In response to this, Pierre states angrily that ‘He [Mathurin] realised that you want to ruin this house, that your warnings betray your desire to destroy our family’. It’s clear that Pierre has been communicating with Lucy on Mathurin’s behalf: Mathurin is uncouth and seemingly impossible to communicate with. Prior to Lucy’s arrival, Pierre shaves and bathes his son. When Lucy retires to her room, Pierre has his servant Ifany send up a love note from Mathurin (in reality written by Pierre) and a red rose. Reading the note provokes desire in the sexually repressed Lucy, and a couple of times she sneaks into Mathurin’s bedroom and tries to rouse him from sleep, one time even grabbing at his penis. However, the sleeping Mathurin simply grunts and shrugs her away, turning back towards the wall. Frustrated once again, Lucy returns to her bedroom and, dreaming of Romilda’s experience with the beast, masturbates with the flower that, she believes, her lover sent her. Lucy’s desire is thus predicated on a lie, a fabrication concocted by Pierre.

Barring the opening sequence’s depiction of Mathurin’s overly-excited gaze directed towards his mating horses, for much of the film’s running time, Borowczyk’s film adopts the form of the costume drama, a predominantly conservative type of cinema. The Earl struggles to make arrangements for the wedding of his son Mathurin to Lucy Broadhurst, overcoming various barriers along the way and finding new obstacles erected in their place. Much of the second half of the film, the climax of the narrative, takes place as the occupants of the chateau (mostly) sleep; left alone in her room, Lucy fantasises about Romilda’s encounter with the beast, as she (Lucy) masturbates with the rose that she believes Mathurin sent her. Lucy’s dream/nightmare/erotic reverie about Romilda’s experiences is presented ambiguously: it’s clear that it functions as a fantasy for Lucy, but given Mathurin’s beastly nature and the hints at the family’s history that are interspersed throughout the plot, it may also be interpreted as an analepsis/flashback of a sort, revealing the past of Mathurin’s family to Lucy in the form of a dream. In Lucy’s dream, Romilda is presented playing the harpsichord in the chateau. Outside is a ewe and its lamb. Romilda hears a mysterious roaring/rumbling sound. The lamb wanders into the woods surrounding the chateau, and Romilda runs after it. She comes into contact with the beast, which is devouring the lamb. As her gaze is torn by the beast and by the entrails on the ground, the look of panic on Romilda’s face is expressed through a close-up. Romilda flees the scene; the beast pursues. During the chase, Romilda’s clothes are ripped from her body. The beast catches up with her, and Romilda attempts to climb a tree to escape from the creature. As she is stuck halfway up the tree, the beast laps at her sex, whilst Romilda inadvertently masturbates the beast to ejaculation with her flailing legs. Romilda manages to escape once more. Again, the beast catches up with her. The beast ravishes Romilda, who is bent over a tree stump. She resists at first, but as the encounter progresses she seems to take pleasure in it. Finally, the beast seems to expire, spent by his liaison with Romilda. She covers the beast’s body in leaves and returns to the chateau.  This sequence presents a parody of the iconography of pornography and is outrageously funny. The beast’s engorged phallus is shown in repeated close-up, and there are numerous ‘money shots’ throughout the sequence: the beast ejaculates with alarming frequency. Like most pornographic encounters, the sequence is wordless and virtually silent – except for the beast’s thunderous grumbles, and the insistent harpsichord music by Domenico Scarlatti. At one point, the beast even masturbates with Romilda’s regency wig. When Romilda tries to escape by climbing a tree, she inadvertently stimulates the beast with her feet, again causing the creature to ejaculate; this would be hysterical enough, but at the same time the beast laps at Romilda’s sex with his huge tongue. This moment refers back to the opening sequence, in which Mathurin watches his horses mate. This again is a grotesque parody of pornographic imagery: the stallion’s huge penis is juxtaposed with the mare’s pulsing labia. The stallion’s penis is guided into the mare, and we see in close-up the animalistic thrusting and, also in close-up, the stallion biting the shoulder of the mare. As the stallion withdraws, seminal fluid spilling on the floor, we are presented with a tight close-up of Mathurin leering at the spectacle. Then, in a shot which brings us full circle with the animalistic cunnilingus shown in Romilda’s encounter with the beast at the end of the film, we are shown an outrageous shot of the stallion lapping at the mare’s sex as his semen dribbles out of it. Both sequences, which bookend the narrative, are grotesque, outrageous and deeply, blackly funny. In light of this, the beast’s unconvincing appearance, criticised by some as a weakness of the production, seems incredibly playful – just another technique Borowczyk uses to emphasise his parody of the conventions of pornography, the costume drama and the monster picture. This sequence presents a parody of the iconography of pornography and is outrageously funny. The beast’s engorged phallus is shown in repeated close-up, and there are numerous ‘money shots’ throughout the sequence: the beast ejaculates with alarming frequency. Like most pornographic encounters, the sequence is wordless and virtually silent – except for the beast’s thunderous grumbles, and the insistent harpsichord music by Domenico Scarlatti. At one point, the beast even masturbates with Romilda’s regency wig. When Romilda tries to escape by climbing a tree, she inadvertently stimulates the beast with her feet, again causing the creature to ejaculate; this would be hysterical enough, but at the same time the beast laps at Romilda’s sex with his huge tongue. This moment refers back to the opening sequence, in which Mathurin watches his horses mate. This again is a grotesque parody of pornographic imagery: the stallion’s huge penis is juxtaposed with the mare’s pulsing labia. The stallion’s penis is guided into the mare, and we see in close-up the animalistic thrusting and, also in close-up, the stallion biting the shoulder of the mare. As the stallion withdraws, seminal fluid spilling on the floor, we are presented with a tight close-up of Mathurin leering at the spectacle. Then, in a shot which brings us full circle with the animalistic cunnilingus shown in Romilda’s encounter with the beast at the end of the film, we are shown an outrageous shot of the stallion lapping at the mare’s sex as his semen dribbles out of it. Both sequences, which bookend the narrative, are grotesque, outrageous and deeply, blackly funny. In light of this, the beast’s unconvincing appearance, criticised by some as a weakness of the production, seems incredibly playful – just another technique Borowczyk uses to emphasise his parody of the conventions of pornography, the costume drama and the monster picture.

La bête began life as an adaptation of Prosper Mérimée’s 1869 novella/‘conte fantastique’ Lokis. Set in Lithuania, Lokis focuses on Michel, a young man whose mother was raped by a bear. Believed to be a half-beast, Michel displays crude, animalistic behaviour throughout the novella, and at the climax he murders his bride on the day of their wedding, biting her throat, before fleeing into the forest. Robin Mackenzie suggests that Lokis offers ‘a transformation, indeed inversion, of the Beauty and the Beast story, with Beauty transforming man into beast rather than beast into man’ (2000: 196). It’s a novella that, like La bête, explores the oppositions between ‘culture and nature, rational and irrational, conscious and unconscious’ (ibid.). Borowczyk planned to adapt this story into a feature film in 1972, but eventually filmed it (as ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’) with the intention of including it in his portmanteau picture Immoral Tales. (The ‘Beast of Gévaudan’ was a dog-wolf hybrid that was said to have been responsible for a series of attacks in the Gévaudan province, now part of the Lozère department, during the 1760s.) The story was eventually dropped from Immoral Tales, and Borowczyk used the footage as the nightmare/dream sequence within La bête, building the rest of the film’s narrative around it. La bête began life as an adaptation of Prosper Mérimée’s 1869 novella/‘conte fantastique’ Lokis. Set in Lithuania, Lokis focuses on Michel, a young man whose mother was raped by a bear. Believed to be a half-beast, Michel displays crude, animalistic behaviour throughout the novella, and at the climax he murders his bride on the day of their wedding, biting her throat, before fleeing into the forest. Robin Mackenzie suggests that Lokis offers ‘a transformation, indeed inversion, of the Beauty and the Beast story, with Beauty transforming man into beast rather than beast into man’ (2000: 196). It’s a novella that, like La bête, explores the oppositions between ‘culture and nature, rational and irrational, conscious and unconscious’ (ibid.). Borowczyk planned to adapt this story into a feature film in 1972, but eventually filmed it (as ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’) with the intention of including it in his portmanteau picture Immoral Tales. (The ‘Beast of Gévaudan’ was a dog-wolf hybrid that was said to have been responsible for a series of attacks in the Gévaudan province, now part of the Lozère department, during the 1760s.) The story was eventually dropped from Immoral Tales, and Borowczyk used the footage as the nightmare/dream sequence within La bête, building the rest of the film’s narrative around it.

The film proved controversial with the BBFC owing to its overriding theme of bestiality, not to mention the suggestion in the nightmare/dream sequence that Romilda begins to enjoy the assault that the beast enacts upon her, a return of the ‘rape myth’ that was at least in part responsible for the consternation that surrounded the classification of Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs in 1971. However, the theme of bestiality appears subtly in a number of fairy tale narratives, such as ‘Beauty and the Beast’ and ‘Little Red Cap’/‘Little Red Riding Hood’. Ernest B Shoedsack and Merian C Cooper’s King Kong (1933), a variation of ‘Beauty and the Beast’, offers one of the strongest explorations of this theme in mainstream cinema, but it has also formed the focus of art films such as Nagisa Ôshima’s Max mon amour (1986); and in many ways, it seems positively blasé in the light of the current surge of post-Twilight paranormal romance fiction, which often features love that transcends the boundaries of human and beast (werewolf, vampire, etc).  When the film was first submitted to the BBFC for classification in 1977, in a pre-cut version which removed some of the masturbation footage and reduced the length of the pivotal nightmare/dream sequence involving Romilda and the titular beast, James Ferman suggested in a letter to the distributor, New Realm Pictures, that the film was still problematic and that he didn’t wish to suggest cuts that may ‘damage the film artistically’ (Ferman, quoted in BBFC, 2014: np). Ferman identified as specific problem areas the scenes of copulating horses, the drawing that Lucy finds on the rear of the frame depicting a dog mounting a woman, close-ups of female genitals, and several moments within the nightmare/dream sequence (the beast rubbing his penis against a tree, masturbating and placing his head between Romilda’s legs, and the ‘climax’ of the encounter, depicting the beast ejaculating over Romilda). However, what was more challenging was ‘the theme itself, the most explicit treatment of bestiality we have ever had, even given in this case it is treated as a fantasy’ (Ferman, quoted in ibid.). When the film was first submitted to the BBFC for classification in 1977, in a pre-cut version which removed some of the masturbation footage and reduced the length of the pivotal nightmare/dream sequence involving Romilda and the titular beast, James Ferman suggested in a letter to the distributor, New Realm Pictures, that the film was still problematic and that he didn’t wish to suggest cuts that may ‘damage the film artistically’ (Ferman, quoted in BBFC, 2014: np). Ferman identified as specific problem areas the scenes of copulating horses, the drawing that Lucy finds on the rear of the frame depicting a dog mounting a woman, close-ups of female genitals, and several moments within the nightmare/dream sequence (the beast rubbing his penis against a tree, masturbating and placing his head between Romilda’s legs, and the ‘climax’ of the encounter, depicting the beast ejaculating over Romilda). However, what was more challenging was ‘the theme itself, the most explicit treatment of bestiality we have ever had, even given in this case it is treated as a fantasy’ (Ferman, quoted in ibid.).

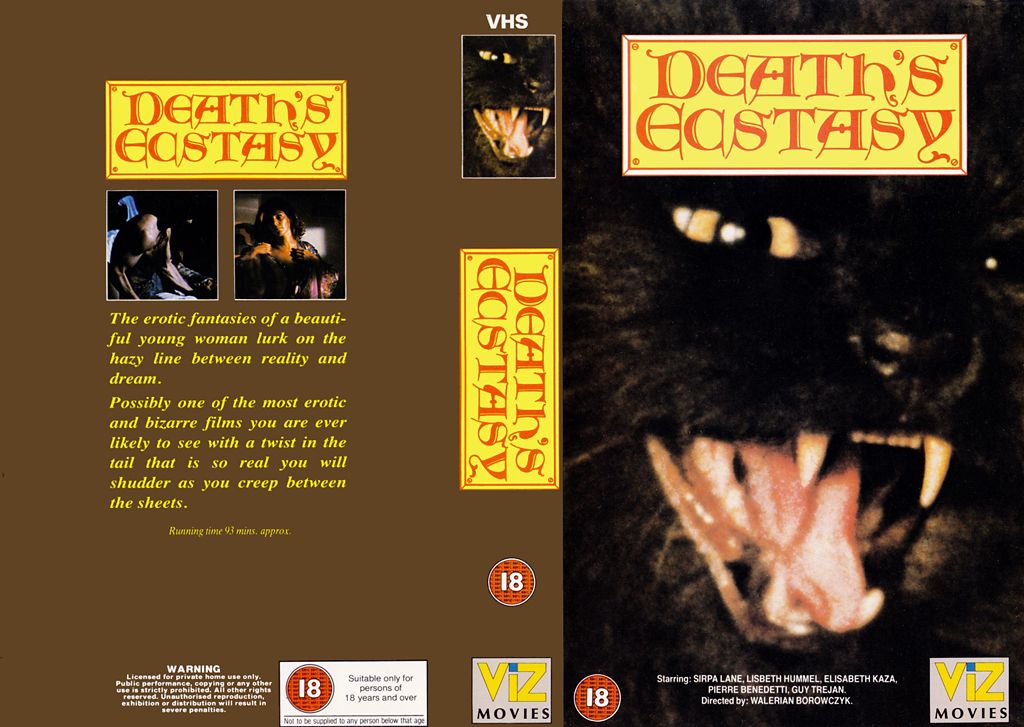

In response to Ferman’s comments, the distributor cut the film further and resubmitted it in early 1978, but the BBFC decided to reject it, again citing the general theme of bestiality as a reason for this decision: ‘none of us feels confident that the film could not accurately be described as a study in bestiality’, Ferman said in a letter to the distributor explaining the decision to reject the film, ‘I realise that it is only simulated bestiality, but there are many forms of sexual activity at which we currently draw the line even when simulated’ (Ferman, quoted in ibid.). Ferman persuaded the General London Council to take a look at the cut version of the film, and the GLC permitted the film to be shown at the Prince Charles theatre. (In his letter to the GLC explaining the reasons for the BBFC’s rejection of the film, Ferman compared La bête explicitly to ‘Beauty and the Beast’, and suggested that ‘it is doubtful whether audiences at the Prince Charles would be likely to complain about a film which is clearly fantasy, and quite beautifully photographed fantasy at that’; Ferman, quoted in ibid.) However, the screening at the Prince Charles theatre was followed by complaints, which provoked the involvement of the Director of Public Prosecutions, who was asked to consider prosecuting the film under the Obscene Publications Act. Sensibly, the DPP concluded that La bête ‘was grossly indecent but absurd’ rather than obscene (quoted in ibid.).  La bête was briefly released on video in the UK by VTC in 1983, a year prior to the Video Recordings Act; this was a cut, English-dubbed version of the picture, running 86 minutes. In 1987, the American version of the film, with the title Death’s Ecstasy (sometimes written as ‘Death’s Ecstacy’) was submitted to the BBFC and passed uncut. This edit of the film, omitting much of the explicit content and some narrative material, was distributed on VHS under the ViZ Movies label. Finally, in 2000 the complete film was submitted to the BBFC for cinema release and passed uncut; a year later, a 94 minute edit, apparently prepared by Borowczyk himself and sometimes labelled a ‘director’s cut’, was passed uncut for home video distribution. This cut of the film retained all of the explicit material but eliminated four minutes of narrative footage, presumably for pacing reasons: (i) a brief scene in which Ifany sneaks into the bathroom after Pierre has groomed Mathurin and conceals some of Mathurin’s hair in an envelope; (ii) a scene in which Ifany brings this envelope to Rammondelo, who removes the hair from the envelope and sniffs it; (iii) a scene in which the cook of the chateau sings whilst setting the table; and (iv) a scene when the Cardinal arrives at the chateau and discusses the issue of bestiality with the priest. La bête was briefly released on video in the UK by VTC in 1983, a year prior to the Video Recordings Act; this was a cut, English-dubbed version of the picture, running 86 minutes. In 1987, the American version of the film, with the title Death’s Ecstasy (sometimes written as ‘Death’s Ecstacy’) was submitted to the BBFC and passed uncut. This edit of the film, omitting much of the explicit content and some narrative material, was distributed on VHS under the ViZ Movies label. Finally, in 2000 the complete film was submitted to the BBFC for cinema release and passed uncut; a year later, a 94 minute edit, apparently prepared by Borowczyk himself and sometimes labelled a ‘director’s cut’, was passed uncut for home video distribution. This cut of the film retained all of the explicit material but eliminated four minutes of narrative footage, presumably for pacing reasons: (i) a brief scene in which Ifany sneaks into the bathroom after Pierre has groomed Mathurin and conceals some of Mathurin’s hair in an envelope; (ii) a scene in which Ifany brings this envelope to Rammondelo, who removes the hair from the envelope and sniffs it; (iii) a scene in which the cook of the chateau sings whilst setting the table; and (iv) a scene when the Cardinal arrives at the chateau and discusses the issue of bestiality with the priest.

The version included on this Blu-ray is uncut, with a runtime of 98:21 mins.

Video

The film takes up approximately 27Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and is presented in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. It’s an excellent presentation of the film, a significant upgrade over the various DVDs that have been available. Shot on colour 35mm film stock, much of the film was apparently shot with 50mm lenses (Noël Véry, the camera operator, says that Borowczyk preferred the 50mm focal length because ‘there was no deformation’ of the image), which roughly approximate the field of vision of the human eye – so there’s none of the flattening of perspective that comes with the use of telephoto lenses or the unnatural field of vision associated with wide-angle lenses. The image is detailed and has a strong sense of depth to it. The colour palette of the film is for the most part quite muted, filled with browns and greens, and this is presented nicely in this Blu-ray release: there’s subtle contrast between the rich browns of the wooden wall panels and the deep reds of the leather armchairs that are set in front of them, for example. The grain structure is natural and resolved well within the encode. In all, it’s an extremely pleasing presentation of the film. NB. Some larger screengrabs are contained at the bottom of the page.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track, in French. (An English dub also exists but is not included here.) Some portions of dialogue are in English. Optional English subtitles are included. The audio track is excellent, demonstrating superb range – from the melodic notes of the harpsichord to the deep, discordant grumblings of the beast itself.

Extras

The disc includes an introduction by critic Peter Bradshaw (1:45). Bradshaw sings the praises of this ‘incendiary […] operatic and hilarious film’, saying that Borowczyk ‘had a great sense of the fabula, a great sense of the dreamlike, and a great sense of the […] erotic’. Borowczyk, Bradshaw argues, is comparable to Cocteau and Bunuel, and he still hasn’t ‘properly been appreciated’. The disc includes an introduction by critic Peter Bradshaw (1:45). Bradshaw sings the praises of this ‘incendiary […] operatic and hilarious film’, saying that Borowczyk ‘had a great sense of the fabula, a great sense of the dreamlike, and a great sense of the […] erotic’. Borowczyk, Bradshaw argues, is comparable to Cocteau and Bunuel, and he still hasn’t ‘properly been appreciated’.

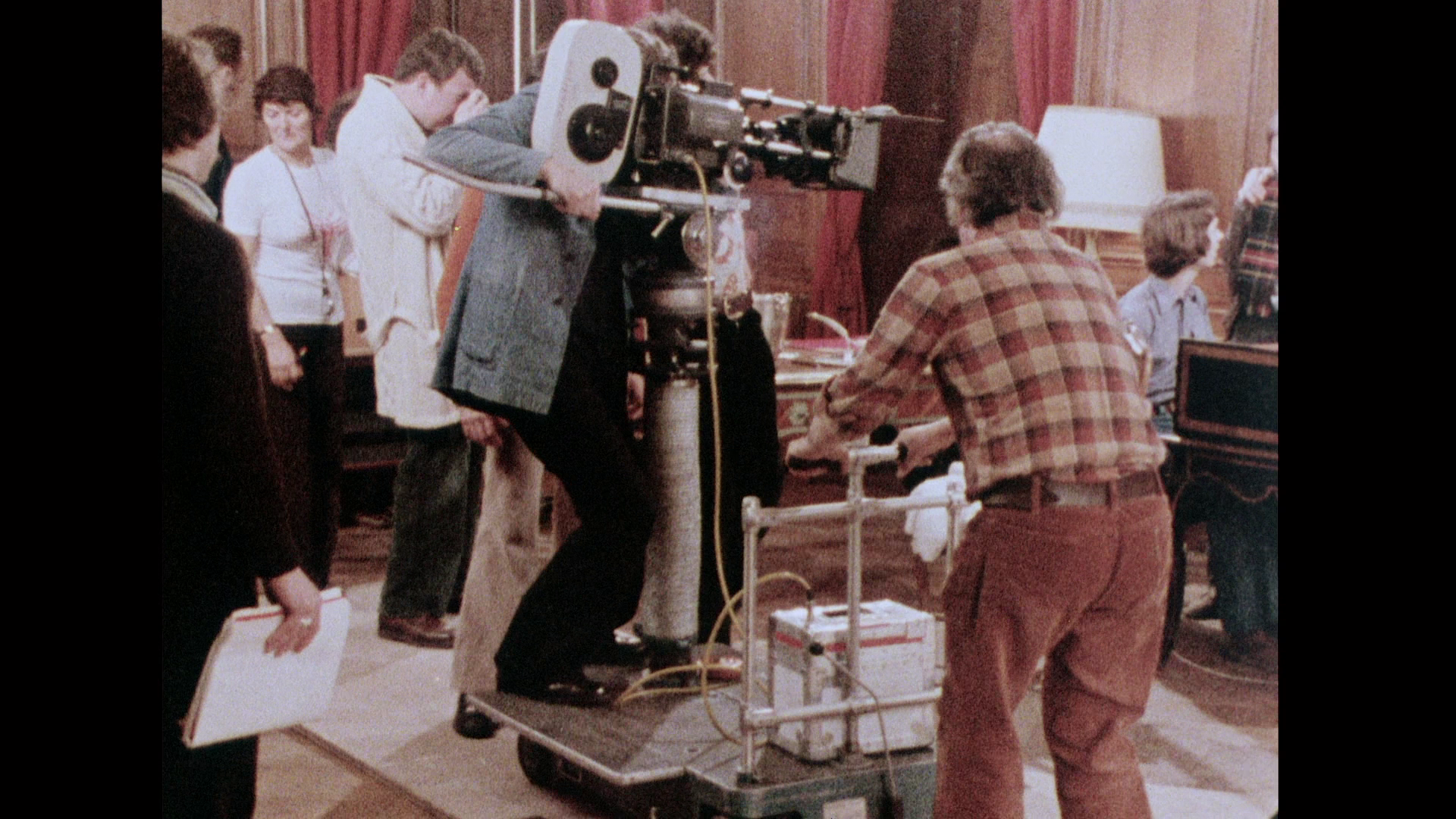

‘The Making of The Beast’ (57:53). This documentary is comprised of still images, text and silent 16mm footage of the production of the film, telling the story of the film’s origins and its production. We get to see Borowczyk setting up shots and directing the actors. This footage is fascinating in itself, but a commentary is also provided by Noël Véry, the camera operator on La bête and a number of other Borowczyk films. ‘Frenzy of Ecstasy: The Evolution of The Beast’ (4:19). This short featurette contains letters and sketches from Borowczyk to the producer, showing how Borowczyk intended to create the titular beast. Also included is an outline for Borowczyk’s proposed sequel to La bête, ‘Motherhood’, which he tried to get off the ground during the 1990s. ‘Venus on the Half Shell’ (1975) (4:39). This is Borowczyk’s short film from 1975, focusing on Bona Tibertelli de Pisis’ erotic artwork. Bona Tibertelli de Pisis was the wife of André Peyre de Mandiargues, author and poet, whose novel Le Marge formed the basis for Borowczyk’s 1976 film. Trailer (3:54).

Overall

La bête is probably not the ‘best’ place to start with Arrow’s wonderful new Borowczyk box (in the interests of full disclosure, I chose to start with this film because I have a long love affair with it but, despite this, hadn’t revisited it since the early 2000s), but the strengths of this disc are the strengths of the set as a whole: loving restorations of the films, and some superb contextual material. (I can see myself repeating this phrase throughout the reviews of all of the discs included in this set, and also released invididually.) La bête is probably not the ‘best’ place to start with Arrow’s wonderful new Borowczyk box (in the interests of full disclosure, I chose to start with this film because I have a long love affair with it but, despite this, hadn’t revisited it since the early 2000s), but the strengths of this disc are the strengths of the set as a whole: loving restorations of the films, and some superb contextual material. (I can see myself repeating this phrase throughout the reviews of all of the discs included in this set, and also released invididually.)

La bête is a fascinating film which offers a revolutionary challenge to easy attempts to draw differences between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture (or between ‘art’ and ‘pornography’, or even between ‘man’ – or aristocrat – and ‘beast’): it’s not an easy film to pigeon hole. Like the pornographic writings of de Sade (or, in more recent currency, the films of a director such as Luis Bunuel), La bête offers a savagely satirical depiction of authority. The priest in the film is a pederast; the aristocrats are denounced by the Cardinal as pagans with ‘unsavoury habits’, and ultimately their lineage can be traced (apparently) to the romp between Romilda and the titular beast in the woods surrounding the chateau. They are the products (monsters?) of this unwholy union. Mathurin bears the proof of this encounter upon his body: his torso is matted with hair, and he has both a tail and a hand that is like that of his beastly ancestor (curiously like the claw of Satan in Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw, 1971). The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray disc is exemplary, in terms of both image and sound. The contextual material is fascinating, especially the hour long ‘The Making of The Beast’, with its marriage of still images, text, commentary by Noël Véry, and 16mm behind-the-scenes footage. It’s a particularly fascinating ‘extra’. Arrow’s Borowczyk releases are uniformly excellent, whether one purchases them via the limited edition Camera Obscura set or as standalone discs. The Camera Obscura set is arguably the release of the year, and, focusing on the specific film at hand, La bête is a picture that has lost none of its revolutionary charge – and this Blu-ray offers far and away the best way to watch the film. Thank you, Arrow! References: BBFC, 2014: ‘Case Study: La Bete – The Beast’. [Online.] http://www.bbfc.co.uk/case-studies/la-bete-beast Bird, Daniel, 2011: ‘Walerian Borowczyk’. In: Bingham, Adam (ed), 2011: Directory of World Cinema, Volume 8. London: Intellect Books Fudge, Erica, 2007a: ‘“Onely Proper Unto Man”: Dreaming and Being Human’. [Online.] http://www.google.co.uk/url?q=http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/29532/1/Onely_proper_unto_man_for_strathprints_1_.doc&sa=U&ei=oQQCVMaSIMvWauqcgfgE&ved=0CBwQFjAC&sig2=BezckWvDRyDlfvCfz0Nabw&usg=AFQjCNHJnMC4v0X3CzIDJ2h0Dyj-nn0rYw Fudge, Erica, 2007b: ‘“Onely Proper Unto Man”: Dreaming and Being Human in the Renaissance’. In: Hodkin, Katharine et al (eds), 2007: Reading the Early Modern Dream: The Terrors of the Night. London: Routledge Khapaeva, Dina, 2012: Nightmare: From Literary Experiments to Cultural Project. Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV Mackenzie, Robin, 2000: ‘Space, Self and the Role of the Matecznik in Merimee’s Lokis’. Forum for Modern Language Studies (XXXVI)2: 196-208 Malcolm, Derek, 2000: ‘Walerian Borowczyk: Blanche’. The Guardian. [Online.] http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2000/jun/08/artsfeatures2 Riviere, Janine, 2013: ‘Demons of Desire or Symptoms of Disease? Medical Theories and Popular Experiences of the “Nightmare” in Premodern England’. In: Plane, Anne Marie & Tuttle, Leslie (eds), 2013: Dreams, Dreamers and Visions: The Early Modern Atlantic World. University of Pennsylvania Press: 49-71

|

|||||

|