|

|

Blanche (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd September 2014). |

|

The Film

Blanche (Walerian Borowczyk, 1971)  This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release. This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release.

NB. Links to reviews of the other Borowczyk discs will be added to this review as they go ‘live’ over the coming week. Our review of The Beast (1975) can be found here. Our review of Goto, Isle of Love (1968) can be found here. Our review of Immoral Tales (1974) can be found here. - Our review of Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation can be found here. Based on Juliusz Slowacki’s 1839 play Mazeppa, but relocating the action from 17th Century Poland (which was the setting for the play) to 13th Century France, Borowczyk’s Blanche (1971) tells the story of Blanche (played by Borowczyk’s wife Ligia Branice), the younger wife of an ageing Count (Michel Simon). The film begins with the impending arrival of the King (Georges Wilson). Blanche is warned by Madame d’Harcourt (Denise Péronne) of the King’s lustful page Bartolomeo (Jacques Perrin). Meanwhile, the castle is also visited by the Count’s son Nicolas (Lawrence Trimble), who has returned home from Egypt, having been promoted to the rank of Captain in the French army. Blanche discovers that the rumours expressed by Madame d’Harcourt about Bartolomeo have a grounding in reality: whilst alone with Blanche, he makes advances towards her and, when she attempts to escape, tries to prevent her from leaving the room. Later that evening, upon hearing of Bartolomeo’s advances towards Blanche (and aware of how irresistible most women, Blanche excepted, seem to find Bartolomeo), the King dresses in Bartolomeo’s cloak with the intention of sneaking into Blanche’s chambers and seducing her. However, he is stopped by Nicolas who, having also heard of Bartolomeo’s advances towards his stepmother, fends off the King (who Nicolas believes to be Bartolomeo) with a sword, wounding the King’s hand in the process. When the King returns to his chambers with a wounded hand, Bartolomeo also cuts his hand, so that suspicion will not fall upon the King. Angered, and believing Bartolomeo to be the culprit, the Count confronts the King, insisting that Blanche is ‘above suspicion, Your Majesty. She is a saintly person’. The King sends Bartolomeo away from the castle, to deliver a letter to the commander at Beaufort. Bartolomeo is blocked in his errand by Nicolas, who duels with him for the honour of Blanche. Bartolomeo deduces that Nicolas is also in love with Blanche. When the duel is ended, Nicolas and Bartolomeo come to a truce; Bartolomeo reads the letter the King has given him to deliver, which reveals that the King plans to lay siege to the castle of the Count and also demands that Bartolomeo be ‘confined to the tower until further orders’.  Bartolomeo returns to the castle, intending to inform Blanche of the King’s plans. However, as he is hiding in Blanche’s chambers, the Count demands that the bedchamber be walled up, sealing Bartolomeo in there alive. The Count also has Blanche imprisoned, confined to a cage-like room. Believing Blanche to be in love with Bartolomeo, Nicolas confronts her, threatening her with violence unless she declare her love for the King’s page. Meanwhile, the King returns to the castle and realises that Bartolomeo has been sealed within Blanche’s bedchamber; he demands the wall to be dismantled. Fortunately, Bartolomeo is alive. The Count confronts the King over Bartolomeo’s presumed conduct (‘Have I not the right to kill an adulterer, sire?’); Bartolomeo demands ‘trial by combat’. Nicolas fights in the place of the Count but is mortally wounded. In response, the Count demands Bartolomeo remain at the castle for one day, whilst the King returns to his own. Bartolomeo returns to the castle, intending to inform Blanche of the King’s plans. However, as he is hiding in Blanche’s chambers, the Count demands that the bedchamber be walled up, sealing Bartolomeo in there alive. The Count also has Blanche imprisoned, confined to a cage-like room. Believing Blanche to be in love with Bartolomeo, Nicolas confronts her, threatening her with violence unless she declare her love for the King’s page. Meanwhile, the King returns to the castle and realises that Bartolomeo has been sealed within Blanche’s bedchamber; he demands the wall to be dismantled. Fortunately, Bartolomeo is alive. The Count confronts the King over Bartolomeo’s presumed conduct (‘Have I not the right to kill an adulterer, sire?’); Bartolomeo demands ‘trial by combat’. Nicolas fights in the place of the Count but is mortally wounded. In response, the Count demands Bartolomeo remain at the castle for one day, whilst the King returns to his own.

Bartolomeo tells Blanche that Nicolas died for her. Overcome with grief, Blanche apparently dies. Meanwhile, the Count has Bartolomeo tied to horses, dragged and chased by hounds – and Bartolomeo informs the Count that the secret Bartolomeo has kept from the Count ‘will surely kill you’. Slowacki’s play was based on a story from the life of Ivan Mazeppa, a commander of the Cossacks in the Ukraine from 1687 to 1708. One of the possibly apocryphal stories from Mazeppa’s youth, during his time as a page in the court of King John II Casimir Vasa, details an affair Mazeppa conducted with a Countess. The Countess’ husband was much older than her, and upon discovering the affair, the Count strapped the naked Mazeppa to a wild horse, sending it running through the countryside. The veracity of this story is in doubt, although Voltaire wrote about it in his 1731 volume History of Charles XII, King of Sweden. The story formed the basis for works by numerous writers and artists, including Lord Byron’s 1819 poem ‘Mazeppa’ (in which Mazeppa emerges as a Byronic hero in the vein of Don Juan), Horace Vernet’s 1826 painting ‘Mazeppa and the Wolves’, Louis Boulanger’s ‘Mazeppa’ (1827), John Frederick Herring’s 1833 ‘Mazeppa Pursued by Wolves’ and Theodore Géricault’s ‘The Page Mazeppa’ from 1823. Géricault’s depiction of Mazeppa’s ‘wild ride’ is often compared to images of the Crucifixion or a pieta painting: it depicts the suffering of Mazeppa as he is strapped to the horse, with Mazeppa being painted in almost saintly light (see, for example, Voss, 2012: np). (Bartabas’ 1993 film Mazeppa focuses on Theodore Géricault’s fetishistic fascination with horsecraft, climaxing with a sequence in which Géricault re-enacts Mazeppa’s wild ride.) Borowczyk’s Blanche subverts this chauvinistic legend by not only focusing on the female object of Mazeppa’s desire (the King’s page Bartolomeo fulfils Mazeppa’s role in the story; Blanche is a clear stand-in for the Countess of the legend) rather than on the ‘Don Juan’ figure, but also by allowing her name to grace the title of the film (significantly, the film is called ‘Blanche’, not ‘Bartolomeo’).  Despite this subversion of the Mazeppa legend’s approach towards gender politics, Blanche follows the structure of Slowacki’s play quite closely, the script including a number of narrative events from the play: the duel between Bartolomeo/Mazeppa and Nicolas/Zbigniew that results in a reconciliation; the return of the King at the end of the narrative; the suicide of Nicolas/Zbigniew; and the sequence in which Bartolomeo/Mazeppa cuts his own hand in order to save the King from embarrassment after his failed attempt to enter the chambers of Blanche (Amelia, in Slowacki’s play). Despite this subversion of the Mazeppa legend’s approach towards gender politics, Blanche follows the structure of Slowacki’s play quite closely, the script including a number of narrative events from the play: the duel between Bartolomeo/Mazeppa and Nicolas/Zbigniew that results in a reconciliation; the return of the King at the end of the narrative; the suicide of Nicolas/Zbigniew; and the sequence in which Bartolomeo/Mazeppa cuts his own hand in order to save the King from embarrassment after his failed attempt to enter the chambers of Blanche (Amelia, in Slowacki’s play).

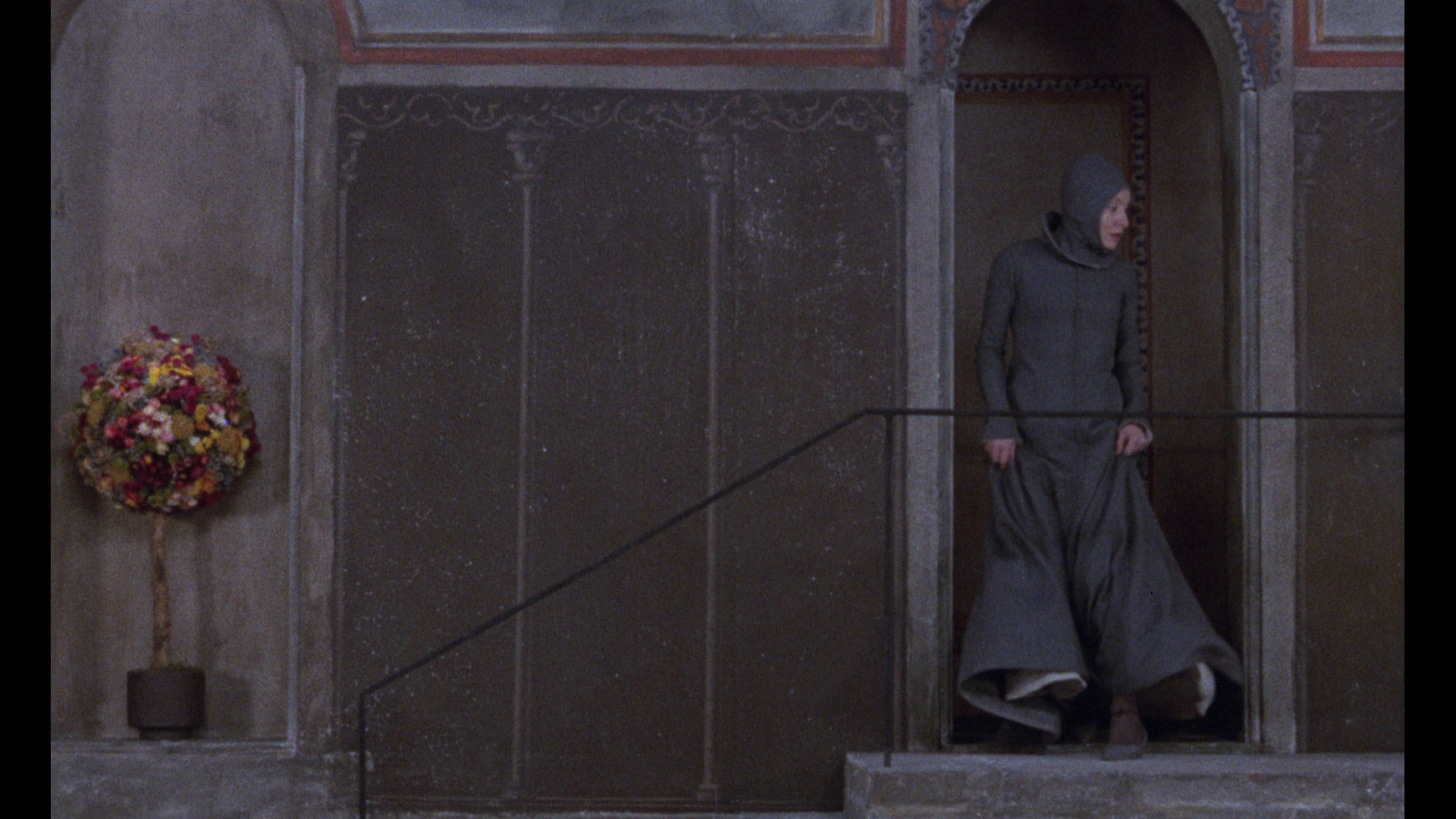

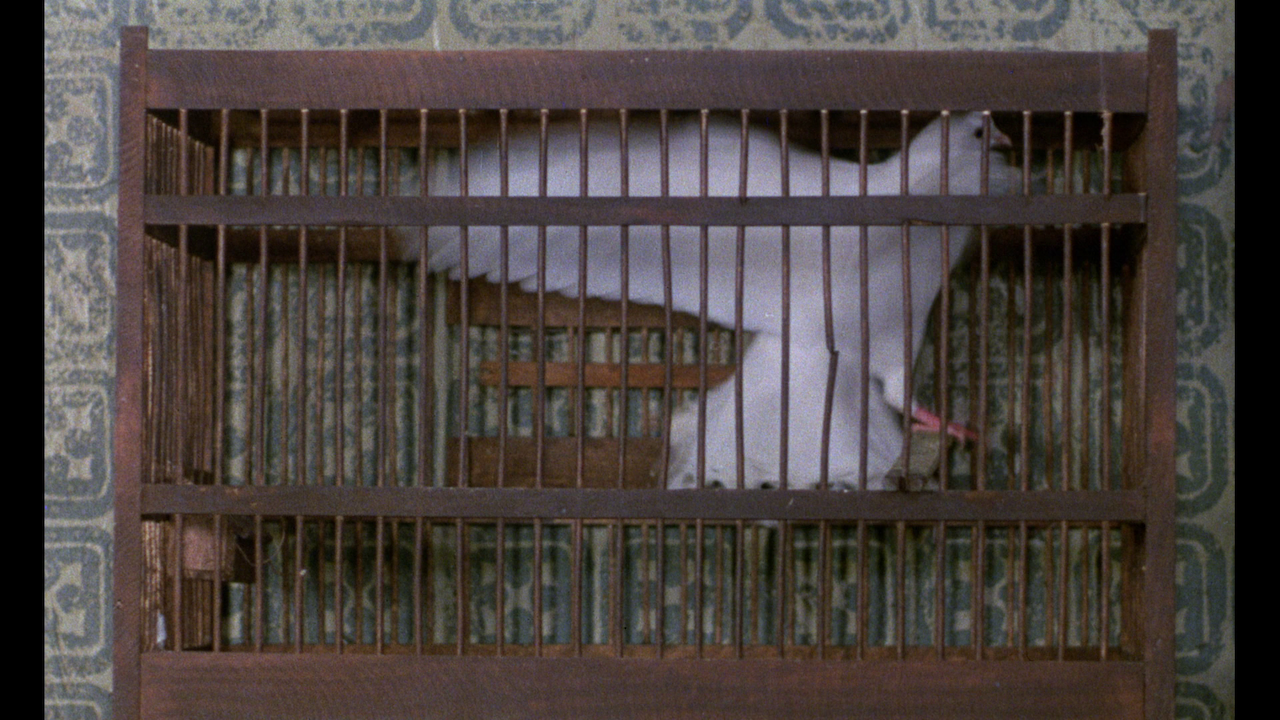

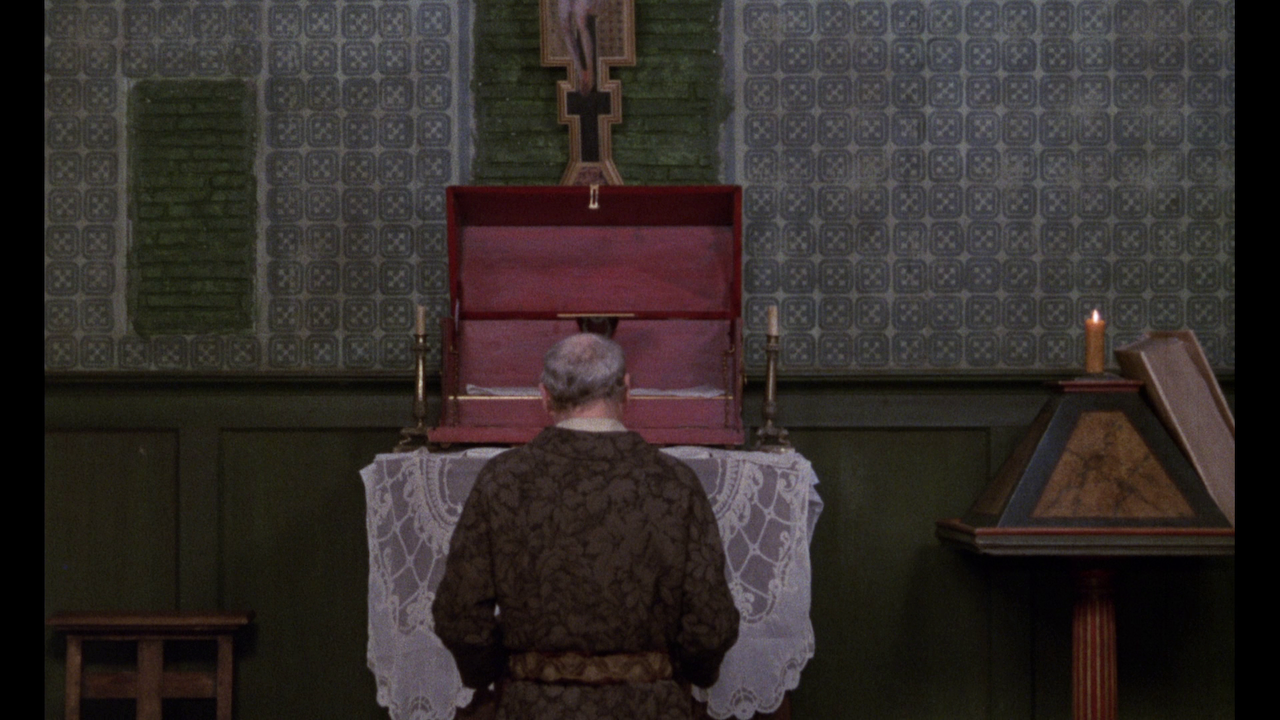

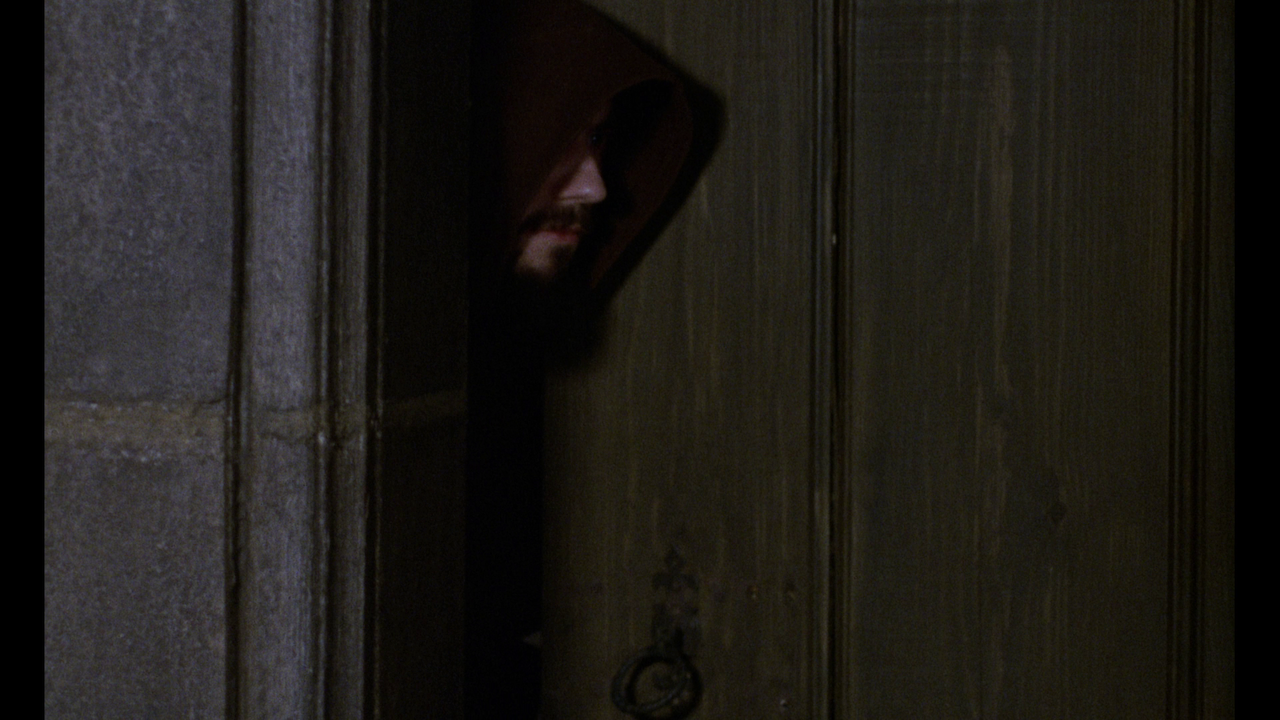

Blanche marked the end of an era within Borowczyk’s career: subsequent films would see him labeled as a director of erotica. However, here Borowczyk displays the fascination with human sexuality and attitudes towards sex that characterise later, more explicit, films such as Le marge (Streetwalker, 1976) and Ars amandi (The Art of Love, 1983). Certainly, Blanche is a film that is to some extent focused on sexual etiquette and mores, a leitmotif throughout Borowczyk’s body of work as a whole. Birds and animals are, of course, another leitmotif in Borowczyk’s work generally. La bęte (1975) foregrounds Borowczyk’s symbolic use of animals, with its snails, horses and, of course, the titular beast that lives in the woods surrounding the chateau. Here in Blanche, animals are symbolic of characters’ natures: the randy Bartolomeo and King are equated with a mischievous monkey which frequently appears in scenes with them. The monkey flits about the room, hiding behind objects or clambering across furniture. Meanwhile, Blanche is associated with the caged dove which she keeps in her chambers. The opening montage equates Blanche with the dove by intercutting shots of Blanche stepping out of her bath and preparing for the feast, shots of the dove in its cage, and long shots of a turret of the castle which make the castle appear to be another type of cage. This is reinforced in the dialogue when the King traps Blanche in a corridor and tells her, ‘You are withering in the desert. The castle is pleasantly situated by as gloomy as a Holy Land prison [….] Do you not wish for change? In your place, I would be dead already’. (Earlier, Madame d’Harcourt has also asked Blanche if she feels like a caged bird cooped up in the castle.) After the Count has had Bartolomeo walled up in Blanche’s bedchamber, he also has Blanche placed in a cage-like prison where the once-sympathetic Nicolas confronts her, threatening to ‘crush your little hands if you don’t confess you love him [Bartolomeo]’.  The theme of entrapment runs throughout the film: it’s startling how many scenes involve characters either crossing thresholds, entering or leaving rooms, or discovering thresholds blocked and their entry/egress prevented. (Throughout the film, windows and doorways also act as secondary frames within the film frame. Characters spy on other characters by peeking through cracks in doors or observing through windows, suggesting a conspiracy taking place behind the scenes.) Bartolomeo’s entry into the castle is unusual. He sneaks into the room where the reception for the King is being held. ‘How did you get here?’, Bartolomeo is asked by Madam d’Harcourt. ‘By the window, madam’, he says. ‘Mind you do not leave the same way’, the King tells Bartolomeo in jest. When Bartolomeo tries to seduce Blanche, after the other revelers have left the hall, Blanche tries to escape but finds the door barred. Bartolomeo prevents her from lifting the bar and escaping. Blanche tells him, ‘I am not alone. I have a protector here [Nicolas]’. ‘You will mourn him who dies’, Bartolomeo threatens, before adding, ‘Blanche, all my hope rests in your body’. ‘There is none’, Blanche tells him simply. Most obviously, a threshold is blocked when the Count orders the door to Blanche’s bedchamber be walled up, with Bartolomeo hidden in the room. The theme of entrapment runs throughout the film: it’s startling how many scenes involve characters either crossing thresholds, entering or leaving rooms, or discovering thresholds blocked and their entry/egress prevented. (Throughout the film, windows and doorways also act as secondary frames within the film frame. Characters spy on other characters by peeking through cracks in doors or observing through windows, suggesting a conspiracy taking place behind the scenes.) Bartolomeo’s entry into the castle is unusual. He sneaks into the room where the reception for the King is being held. ‘How did you get here?’, Bartolomeo is asked by Madam d’Harcourt. ‘By the window, madam’, he says. ‘Mind you do not leave the same way’, the King tells Bartolomeo in jest. When Bartolomeo tries to seduce Blanche, after the other revelers have left the hall, Blanche tries to escape but finds the door barred. Bartolomeo prevents her from lifting the bar and escaping. Blanche tells him, ‘I am not alone. I have a protector here [Nicolas]’. ‘You will mourn him who dies’, Bartolomeo threatens, before adding, ‘Blanche, all my hope rests in your body’. ‘There is none’, Blanche tells him simply. Most obviously, a threshold is blocked when the Count orders the door to Blanche’s bedchamber be walled up, with Bartolomeo hidden in the room.

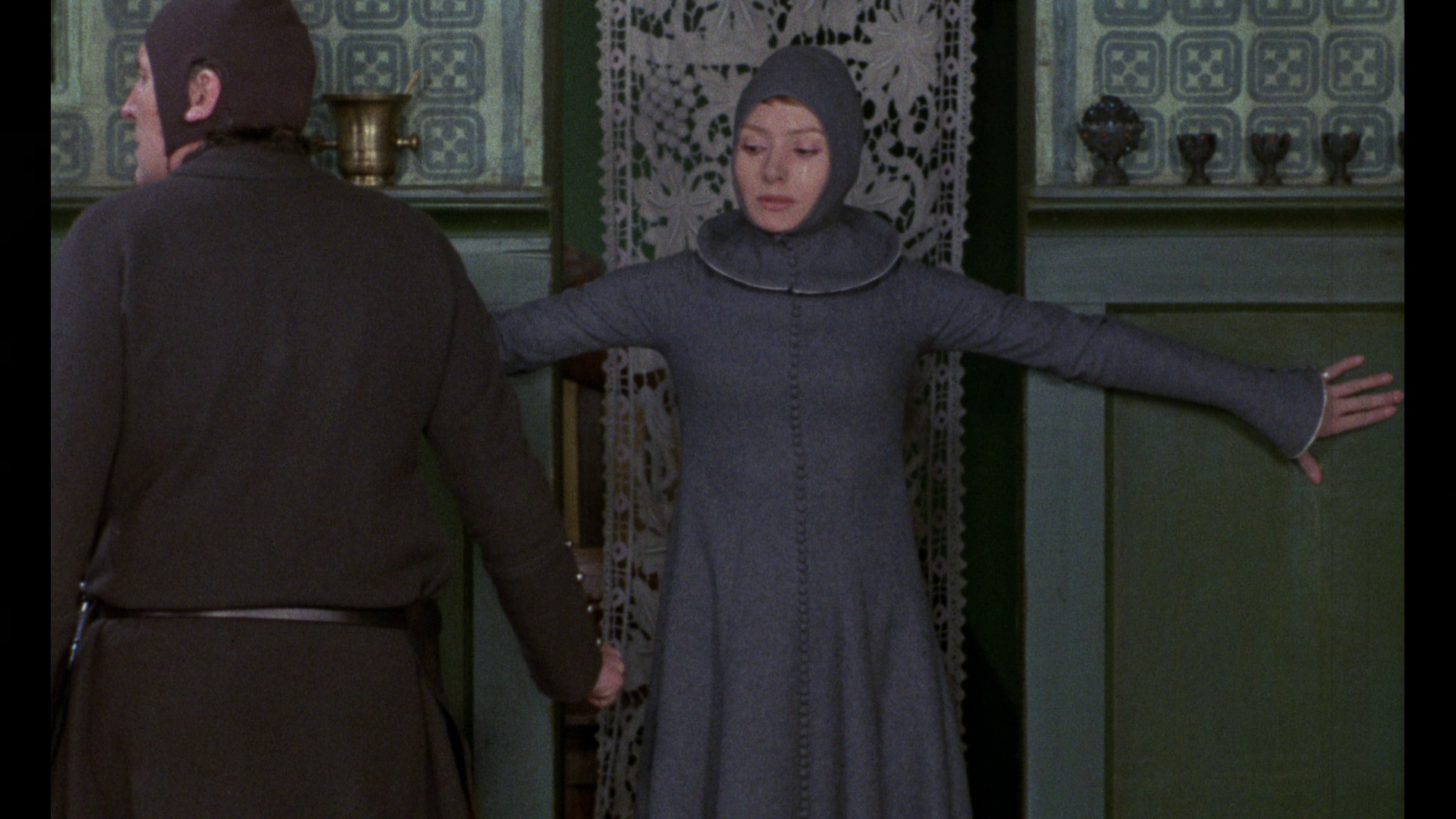

Bartolomeo is depicted as a Don Juan-type figure whose reputation precedes him. ‘You shall see how his roguish glance breaks all hearts’, Madame d’Harcourt tells Blanche, adding, ‘But his own heart is like a city gate. As one enters, another leaves’. However, Bartolomeo is a young, immature man: ‘He is still a beardless boy’, Madame d’Harcourt confesses, ‘but what stories are told about him! A threat to women, a serpent […] They say his saddle is braided with his lovers’ hair’. Meanwhile, Nicolas buries his desire for Blanche, and it’s something of a surprise when it bubbles to the surface. The older Madame d’Hardcourt flirts with him when he arrives at the castle: ‘Do not become a philanderer like all captains’, she tells him upon discovering that he has been promoted. Then she asks him about his relationship with Blanche: ‘Have you the proper respect for such a young mother?’, she enquires.  Blanche herself is an innocent naďf, unaware of the spell she casts over the men around her – a product of their perception of the world, rather than anything intrinsic to Blanche. In the opening sequence, Blanche is naked and thus revealed; after she steps out of her bath, she covers up and remains totally covered (repressed?) throughout the film. She is a passive agent within the narrative: events happen around her, and the male characters gravitate towards her, but she does little to drive the narrative forwards, other than to spurn the male characters’ advances towards her. Borowczyk frequently cuts to close-ups of Blanche’s face as she reacts to the events around her: her face is lit in a way that suggests innocence and piety. Her rebuttals to the advances of the men are gentle (‘You may think it is rustic simplicity but… I am displeased by your words’, she tells Bartolomeo on his first attempt to seduce her), but as the narrative progresses she becomes increasingly unable to express herself in words: her resistance to the male characters’ attempts to seduce her are, in later sequences in the film, expressed through physical gestures (a turning away of the head; tears; twisting of the body; whimpers and cries) rather than words. Blanche’s passivity is reinforced when Bartolomeo demands ‘trial by combat’ and Nicolas steps in to fight for his father (and for the honour of Blanche). Unable to intervene, Blanche collapses to the floor. The Count says that Blanche’s blessing means death. He commands her to bless Bartolomeo, holding her hand and moving it as if he were a puppeteer, to make the sign of the cross in the direction of Bartolomeo. Blanche herself is an innocent naďf, unaware of the spell she casts over the men around her – a product of their perception of the world, rather than anything intrinsic to Blanche. In the opening sequence, Blanche is naked and thus revealed; after she steps out of her bath, she covers up and remains totally covered (repressed?) throughout the film. She is a passive agent within the narrative: events happen around her, and the male characters gravitate towards her, but she does little to drive the narrative forwards, other than to spurn the male characters’ advances towards her. Borowczyk frequently cuts to close-ups of Blanche’s face as she reacts to the events around her: her face is lit in a way that suggests innocence and piety. Her rebuttals to the advances of the men are gentle (‘You may think it is rustic simplicity but… I am displeased by your words’, she tells Bartolomeo on his first attempt to seduce her), but as the narrative progresses she becomes increasingly unable to express herself in words: her resistance to the male characters’ attempts to seduce her are, in later sequences in the film, expressed through physical gestures (a turning away of the head; tears; twisting of the body; whimpers and cries) rather than words. Blanche’s passivity is reinforced when Bartolomeo demands ‘trial by combat’ and Nicolas steps in to fight for his father (and for the honour of Blanche). Unable to intervene, Blanche collapses to the floor. The Count says that Blanche’s blessing means death. He commands her to bless Bartolomeo, holding her hand and moving it as if he were a puppeteer, to make the sign of the cross in the direction of Bartolomeo.

The male characters act chivalrously, lustfully, patronisingly towards Blanche. All of this is predicated on their patriarchal idealisation of woman and their need/desire to ‘cage’ and possess her. When the Count confronts the King over Bartolomeo’s advances towards Blanche, which are completely unwelcome, the King tries to excuse Bartolomeo’s behaviour by subtly pointing the finger at the victim, Blanche: ‘I know my page’, he says, ‘He cannot resist a glance from pretty eyes’. However, at this stage in the narrative, the Count has complete faith in Blanche, telling the King, ‘My wife is above suspicion, Your Majesty. She is a saintly person’. However, when he discovers Bartolomeo in Blanche’s bedchamber, misreads the situation and demands that Bartolomeo be walled up alive, the Count also begins to suspect Blanche of being unfaithful, and he has her incarcerated. Upon discovering that his son Nicolas is also in love with Blanche, the Count blames his wife: ‘You have poisoned him!’, he declares, calling her a ‘witch’. ‘You have bewitched my son [….] You are a dissembler’, the Count asserts.  In its early sequences, the film resembles a farce (the conventions of the farce would recur throughout Borowczyk’s work, in Contes immoraux, La bęte, Interno di un Convento and Dr Jekyll et les femmes, for example): the enclosed, confined setting; the repetitive elements of the narrative (characters attempting to force themselves onto Blanche, or declare their love for her, and her repeated, usually wordless, rebuttal of their advances); the satirical tone; and the theme of mistaken identity. During their first night at the Count’s castle, after Bartolomeo has unsuccessfully attempted to woo Blanche, the King sneaks out of the chambers he shares with his page, clad in Bartolomeo’s cloak, with the intention of entering Blanche’s chambers and, in the guise of Bartolomeo, seducing her. (Though not stated explicitly, it seems that Bartolomeo and the King often collaborate in this way, Bartolomeo seducing women through his boyish charm and his reputation, and the King sneaking into their bedchambers at night.) The illogicality of the King’s attempt to disguise himself as Bartolomeo is never explained and doesn’t need to be (what happens when the King enters the woman’s chambers, we might ask?): it makes sense within the confines of the farce generally, where disguise, mistaken identity and masquerade are recurring tropes. Some of the dialogue is also deeply funny. When the King returns after Nicolas has wounded him with his sword, the King tells Bartolomeo, ‘He [Nicolas] called you a wretch’. ‘Did you not kill him?’, Bartolomeo asks. ‘I was not offended’, the King says, ‘What do I care if you are called a wretch?’ In another sequence, outside the castle Nicolas gives Blanche a lily. A priest interrupts and declares ‘Lilies are for the church’, before snatching the flower from Blanche’s grasp and wandering off towards the chapel. In its early sequences, the film resembles a farce (the conventions of the farce would recur throughout Borowczyk’s work, in Contes immoraux, La bęte, Interno di un Convento and Dr Jekyll et les femmes, for example): the enclosed, confined setting; the repetitive elements of the narrative (characters attempting to force themselves onto Blanche, or declare their love for her, and her repeated, usually wordless, rebuttal of their advances); the satirical tone; and the theme of mistaken identity. During their first night at the Count’s castle, after Bartolomeo has unsuccessfully attempted to woo Blanche, the King sneaks out of the chambers he shares with his page, clad in Bartolomeo’s cloak, with the intention of entering Blanche’s chambers and, in the guise of Bartolomeo, seducing her. (Though not stated explicitly, it seems that Bartolomeo and the King often collaborate in this way, Bartolomeo seducing women through his boyish charm and his reputation, and the King sneaking into their bedchambers at night.) The illogicality of the King’s attempt to disguise himself as Bartolomeo is never explained and doesn’t need to be (what happens when the King enters the woman’s chambers, we might ask?): it makes sense within the confines of the farce generally, where disguise, mistaken identity and masquerade are recurring tropes. Some of the dialogue is also deeply funny. When the King returns after Nicolas has wounded him with his sword, the King tells Bartolomeo, ‘He [Nicolas] called you a wretch’. ‘Did you not kill him?’, Bartolomeo asks. ‘I was not offended’, the King says, ‘What do I care if you are called a wretch?’ In another sequence, outside the castle Nicolas gives Blanche a lily. A priest interrupts and declares ‘Lilies are for the church’, before snatching the flower from Blanche’s grasp and wandering off towards the chapel.

However, as the narrative of Blanche progresses, events becoming increasingly tragic. (This movement from comedy to tragedy also characterises Slowacki’s play about Mazeppa.) Jessica Milner Davies has noted that ‘farce is both aggressive and festive’ but is often in ‘danger of becoming merely and violently aggressive. The strictness of its rules is necessary to prevent farce from over-balancing into an outright attack upon social conventions of its time’ (2003: 88). Blanche transgresses these rules, to its credit, and does indeed become ‘an outright attack upon social conventions’: the need by men under patriarchy to cage women like doves, to seek to construct an idealised identity for them, and to ‘possess’ them.

Video

Taking up approximately 26Gb of a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, this presentation of Blanche is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The image is detailed with a rich colour palette – lots of deep forest greens and browns, contrasted with more vivid reds. Contrast is strong, which is very helpful as much of the film takes place indoors, in interiors that are sometimes lit very low. Taking up approximately 26Gb of a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, this presentation of Blanche is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The image is detailed with a rich colour palette – lots of deep forest greens and browns, contrasted with more vivid reds. Contrast is strong, which is very helpful as much of the film takes place indoors, in interiors that are sometimes lit very low.

Angela Carter once compared Blanche with Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract: both films, Carter argued, ‘presented the past as mise-en-scene … important for its decorative function, a glamorous commodity’ (Carter, 2013: np). Throughout the film, the costumes and sets are profoundly evocative; likewise, the compositions are fascinating, offering a photographic recreation of the iconography of Medieval tapestries. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

With this film, Borowczyk demonstrates an almost fetishistic approach to period detail that stretches from costume and sets to music. The film’s score was one of the first to wholly use period instruments. The LPCM mono audio track has good range, mostly evident during the sequences that involve music: for example, in the opening sequence in which a man sings falsetto (in an arrangement of song 116 from the Carmina Burana song book). (A female guest asks, ‘What’s his song?’ ‘He’s jousting with a blunt sword’, her male companion responds.) Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes: Introduction by director Leslie Megahey (3:43) Megahey, the director of the haunting Schalken the Painter (1979), talks about his interest in Blanche as ‘the biggest stimulus to the idea that you could do period film differently’. He talks a little about the film’s references to Medieval iconography and the use of flat compositions to allude to the visual conventions of tapestries. The use of Medieval music, Megahey says, is ‘very startling’, and some of the compositions (with a ‘horizontal frame with people coming through it and stopping’, and occasionally with people’s heads cropped by the top of the frame, throwing focus on costume, etc) within the film are something that Megahey says he found deeply inspiring.  'Ballad of Imprisonment: Making Blanche' (28:27) 'Ballad of Imprisonment: Making Blanche' (28:27)

This short documentary focuses on the production of Blanche and features an interview with Patrice Leconte (the second assistant director on the picture), Andrew Heinrich (the assistant director on the picture), camera assistant Noël Véry and associate producer Dominique Duvergé -Ségrétin. Leconte talks about his first encounters with Borowczyk’s animated shorts. Leconte talks about writing about Borowczyk for Cahiers du cinema, and how he became involved in working with his idol. Heinrich reflects on his involvment with the production of Blanche and Borowczyk’s meticulous approach to the shooting of the film, which involved careful examination of sets and props and the use of Medieval paintings as reference points for shot composition. Heinrich also talks about the producer’s shutting down of the shoot owing to the fact that he didn’t want Branice to play the role of Blanche. Noël Véry is also interviewed about his role as camera assistant on the film, and discusses the difficulties in using some more experimental angles during the shooting of the picture, saying Borowczyk was ‘second to none for Méličs-style tricks’. 'Obscure Pleasures: A Portrait of Walerian Borowczyk' (63:15) This is a fascinating hour long examination of Borowczyk’s work, the bulk of which is comprised of a vintage interview with Borowczyk conducted by Keith Griffiths, illustrated with footage from both Borowczyk’s shorts and his feature films. (The documentary has been edited by Daniel Bird.) Borowczyk claims that all artists are both artisans and alchemists, in terms of their almost experimental approach to mixing together different elements. Disney, however, is no alchemist, Borowczyk argues, because he had a ‘formula that was too scientific’ and ‘produced tried and tested results’. There’s also a fascinating discussion of the interest in sexuality that is displayed in Borowczyk’s films, with the great man prickling at the interviewer’s question, ‘How much longer are you going to find it [sex] interesting?’ Borowczyk responds by asserting that ‘everybody’s interested in sex. Always have been’. He asserts that he is not ‘a maker of erotic films as I’m thought to be’. ‘Sexual matters’ are just one element of his films, like ‘landscape or religion’. Borowczyk also talks about the extent to which his work as a graphic artist has shaped his cinema, and the differences between cinema and other art forms: for example, painting. It’s a fascinating examination of Borowczyk’s approach to his films, which would be an interesting ‘primer’ for someone new to Borowczyk’s work. 'Gunpoint' (1972) (11:04) Peter Graham’s 1972 short documentary focuses on hunters in the countryside, and was produced and edited by Borowczyk. 'Behind Enemy Lines: Making "Gunpoint"' (5:15) Peter Graham discusses his collaboration with Borowczyk on ‘Gunpoint’, a documentary about ‘a very stupid sport’ (the shooting of pheasants).

Overall

Blanche is a marvelous film with lavish attention to detail. The narrative follows the structure of Slowacki’s play about Ivan Mazeppa (and the details regarding the legend that surrounds Mazeppa’s youth) but subverts it by shifting focus from the Don Juan figure (Bartolomeo) onto Blanche, making her trials and tribulations the centrepoint of the narrative. Much of the film is played out in Dreyer-esque close-ups of Blanche’s face, as she turns away the men who desire her, or reacts in horror as these men, through their lust, destroy one another. Blanche is a marvelous film with lavish attention to detail. The narrative follows the structure of Slowacki’s play about Ivan Mazeppa (and the details regarding the legend that surrounds Mazeppa’s youth) but subverts it by shifting focus from the Don Juan figure (Bartolomeo) onto Blanche, making her trials and tribulations the centrepoint of the narrative. Much of the film is played out in Dreyer-esque close-ups of Blanche’s face, as she turns away the men who desire her, or reacts in horror as these men, through their lust, destroy one another.

‘This place is bewitched’, the King notes at one point in the narrative, ‘These walls hide strange things’. With such a detailed approach to period detail, the film’s odd, almost surreal elements stand out: notably the monks who spy on the characters throughout the film and, late in the game, reveal themselves to be a team of assassins, with knives hidden in their crucifixes and a Bible that unfolds to become a crossbow(!) (In retrospect, Blanche would make an interesting triple-bill with Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du lac, 1974, and Terrys Jones and Gilliam’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail, 1975.) I had previously only seen this film on VHS, via the tape released by Connoisseur Video in the 1990s. This Blu-ray is a revelation. The presentation of the film is first-class and the contextual material is thorough and fascinating. Whether purchased individually or as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura collection, Arrow’s Borowczyk discs are without doubt amongst the best releases of the year. References Carter, Angela, 2013: Shaking a Leg: Collected Journalism and Writings. London: Random House Davies, Jessica Milner, 2003: Farce. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers (Revised Edition) Nemoianu, Virgil, 1984: The Taming of Romanticism: European Literature and the Age of Biedermeier. Harvard University Press Voss, Tony, 2012: ‘Mazeppa-Maseppa: migration of a Romantic motif’. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 49(2)

|

|||||

|