|

|

Immoral Tales AKA Contes Immoraux

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th September 2014). |

|

The Film

Contes immoraux / Immoral Tales (Walerian Borowczyk, 1974)  This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release. This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release.

NB. Links to reviews of the other Borowczyk discs will be added to this review as they go ‘live’ over the coming week. - Our review of Blanche (1971) can be found here. - Our review of The Beast (1975) can be found here. - Our review of Goto, Isle of Love (1968) can be found here. - Our review of Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation can be found here. Michael Goddard suggests that ‘few filmmakers have done a better job of destroying their reputation both with audiences and with critics than Borowczyk did in the period beginning with Immoral Tales’ (2012: 297). Beginning with Immoral Tales/Contes immoraux (or, arguably, with the 1973 short film ‘A Particular Collection’, also included on this disc), Borowczyk’s films offered ‘a unique type of cinema on the borders between art, eroticism, and exploitation’ (ibid.). This served to alienate ‘those critics who had hailed [his second live-action picture] Blanche as the revelation of a new talented director with a Bunuelian surreal sensibility’ (ibid.). As Daniel Bird notes, Contes immoraux was popular with audiences ‘but left most critics perplexed and hostile’ (Bird, 2011: np). For example, John Simon’s review of Contes immoraux in New York Magazine asserts that with the film, Borowczyk foregrounds an ‘obsession with eroticism and cruelty’ that had been buried in his earlier works; and in exploring this thematic terrain in a more open manner, Borowczyk ‘has ransacked minor literature, yellow journalism, and major historic scandals to make a film’ in which ‘everything [is] merely a feeble pretext for some kinky sexual encounter frenziedly dwelt on but very poorly conveyed’ (1976: 82). Borowczyk’s later pictures struggled to find audiences with fans of either art or exploitation cinema: the films themselves ‘were too artistic to operate as sexploitation films, while too erotic to fit comfortably into art cinema’ (Goddard, op cit.: 297). Goddard argues that part of the ‘project’ of Contes immoraux and the films that Borowczyk made after it – including La bête (The Beast, 1975), Interno di un convento (Behind Convent Walls, 1978) and Dr Jekyll et les femmes (Dr Jekyll and His Women/Bloodbath of Dr Jekyll, 1983) – was to challenge the culturally-constructed dualism ‘between these two realms of high art and eroticism’ (ibid.: 300). This approach, Goddard notes, chimes with the tendency of the various new wave cinemas of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s to ‘mix popular and artistic modes of representation’ (ibid.).  However, regardless of their perceived differences from the earlier films, Contes immoraux and the pictures that followed it contain the same revolutionary charge as the earlier pictures (especially the heavily satiric La bête and Interno di un convento) and also show a continuity with the earlier films in terms of theme and aesthetics: a ‘close examination’ of each of the segments within Contes immoraux ‘reveals a continuation and sophistication of Borowczyk’s already developed surrealist cinematic aesthetics, one can only conclude that it is the mere presence of a more explicit eroticism that these critics found so alarming’ (ibid.: 300). As Michael Richardson notes, ‘[o]nly those who have little imagination in the first place […] would fail to perceive the continuity in Borowczyk’s concerns’ between his earlier shorts and first three feature films, and Contes immoraux and the subsequent features (2006: 114). However, regardless of their perceived differences from the earlier films, Contes immoraux and the pictures that followed it contain the same revolutionary charge as the earlier pictures (especially the heavily satiric La bête and Interno di un convento) and also show a continuity with the earlier films in terms of theme and aesthetics: a ‘close examination’ of each of the segments within Contes immoraux ‘reveals a continuation and sophistication of Borowczyk’s already developed surrealist cinematic aesthetics, one can only conclude that it is the mere presence of a more explicit eroticism that these critics found so alarming’ (ibid.: 300). As Michael Richardson notes, ‘[o]nly those who have little imagination in the first place […] would fail to perceive the continuity in Borowczyk’s concerns’ between his earlier shorts and first three feature films, and Contes immoraux and the subsequent features (2006: 114).

Contes immoraux explores similar thematic territory to Borowczyk’s earlier work. Notably, like Goto, l’île d’amour (Goto, Isle of Love, 1968) and Blanche (1972), Contes immoraux examines the relationships that exist between desire and power (and how sexuality can be exploited by the powerful), and explores the consequences of repression – especially as it is tied to religion. The film’s focus, Michael Richardson argues, is ‘as much […] religious as sexual repression’ (op cit.: 114). However, this theme was somewhat buried for some ‘English-language audience[s], whose religious repressions are not founded in the Catholic ritual so central to French society or more particularly to that of Borowczyk’s native Poland’ (ibid.).  Contes immoraux is a portmanteau picture, which incorporates four impressionistic segments/vignettes which take place in different societies, at different points in history. The film was originally intended to included a fifth vignette, ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’ (‘The True Story of the Beast of Gévaudan’), based loosely on both Prosper Mérimée’s 1869 novella/‘conte fantastique’ Lokis, which Borowczyk had in 1972 planned to adapt into a feature film, and the legend of the ‘Beast of Gévaudan’, a dog-wolf hybrid that was said to have been responsible for a series of attacks in the Gévaudan province (now part of the Lozère department) during the 1760s. This vignette, with its focus on the oppositions between ‘culture and nature, rational and irrational, conscious and unconscious’, would in terms of its thematic content have complimented the other segments within the film quite nicely (Robin Mackenzie, 2000: 196). However, it was considered too much of a change of pace, and on reflection the outrageous visual excesses of this story (in terms of its depiction of the activities of the titular beast) jar with the other segments. As a consequence, the segment was eliminated from the final cut of the picture and the (slightly edited) footage was worked into Borowczyk’s subsequent feature, La bête. Nevertheless, a version of Contes immoraux that includes ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’ is included on this disc, labeled as the ‘L’Age d’Or’ cut and with a runtime of 125:25 mins. Contes immoraux is a portmanteau picture, which incorporates four impressionistic segments/vignettes which take place in different societies, at different points in history. The film was originally intended to included a fifth vignette, ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’ (‘The True Story of the Beast of Gévaudan’), based loosely on both Prosper Mérimée’s 1869 novella/‘conte fantastique’ Lokis, which Borowczyk had in 1972 planned to adapt into a feature film, and the legend of the ‘Beast of Gévaudan’, a dog-wolf hybrid that was said to have been responsible for a series of attacks in the Gévaudan province (now part of the Lozère department) during the 1760s. This vignette, with its focus on the oppositions between ‘culture and nature, rational and irrational, conscious and unconscious’, would in terms of its thematic content have complimented the other segments within the film quite nicely (Robin Mackenzie, 2000: 196). However, it was considered too much of a change of pace, and on reflection the outrageous visual excesses of this story (in terms of its depiction of the activities of the titular beast) jar with the other segments. As a consequence, the segment was eliminated from the final cut of the picture and the (slightly edited) footage was worked into Borowczyk’s subsequent feature, La bête. Nevertheless, a version of Contes immoraux that includes ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’ is included on this disc, labeled as the ‘L’Age d’Or’ cut and with a runtime of 125:25 mins.

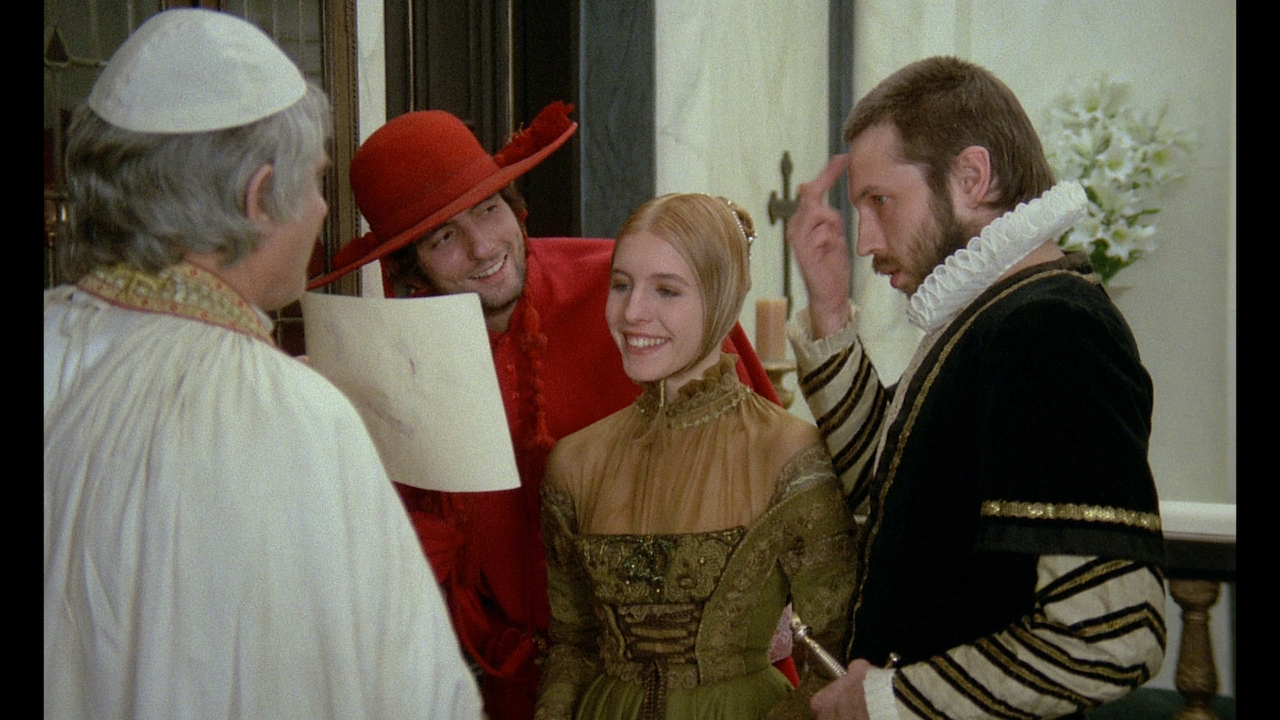

The remaining segments, ‘La Marée’ (‘The Tide’), ‘Thérèse Philosophe’ (‘Thérèse the Philosopher’), ‘Erzsébet Báthory’ and ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ are equally scandalous. ‘La Marée’ is adapted from André Pieyre de Mandiargues’ short story of the same title, which was written for inclusion in a catalogue produced to accompany an exhibition on eroticism that was organised by André Breton in 1959. (The story was also included in a 1971 collection of Mandiargues’ short stories, Mascarets.) ‘Thérèse Philosophe’ takes its title and inspiration from the 1748 pornographic novel by Jean-Baptiste de Boyer (the book itself appears within the segment). ‘Erzsébet Báthory’ focuses on the legend of Erzsébet/Elisabeth Báthory, the ‘Bloody Countess’ whose tendency to bathe in the blood of slaughtered virgins as a means of retaining her youth was first documented in László Turóczi Tragica Historia (1792), and has since formed the basis for numerous novels and films (including Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula, 1971, and Jorge Grau’s Ceremonia sangrienta, 1973, for example). Borowczyk’s take on this legend is informed heavily by surrealist writer Valentine Penrose’s Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante (The Bloody Countess: Atrocities of Erzsébet Báthory) (1962). Finally, ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ juxtaposes an outrageous depiction of an act of incest between Lucrezia Borgia, her father Pope Alexander VI, and her brother Cesare Borgia (a cardinal), with the persecution as a heretic of a man who dares to denounce the corruption of the Catholic church. As the above summary suggests, within Contes immoraux fiction intermingles with fact in a manner that alludes to the devices used by writers of pornographic literature for centuries (where scandalous narratives are often presented as ‘found documents’ in the manner of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill, 1748. Each segment also takes place within a different historical period.  Within a roughly contemporary setting, ‘La Marée’ focuses on a young man, André (Fabrice Luchini), who takes his sixteen year old cousin Julie (Lise Danvers) to a Normandy beach where, stranded by the high tide, he persuades her to commit an act of fellatio upon him as the tide laps against the shore. ‘La Marée’ is unsettling, given Julie’s age and the way in which she is manipulated by her cousin into performing this act. (Given the casting of Fabrice Luchini, the episode feels like a perverse response to Eric Rohmer’s Le genou de Claire/Claire’s Knee, 1970.) The segment’s use of the tide as a metaphor for desire, and its examination of the intersection between desire and power (in terms of the ease with which André persuades Julie to commit this act), are characteristically Borowczyk. But they also have their roots in Mandiargues’ work. (The title of the volume in which this story appears, Mascarets, is both a term used to denote a type of current associated with the changing of the tide, and a slang word taken to refer to the moment of ejaculation.) Within a roughly contemporary setting, ‘La Marée’ focuses on a young man, André (Fabrice Luchini), who takes his sixteen year old cousin Julie (Lise Danvers) to a Normandy beach where, stranded by the high tide, he persuades her to commit an act of fellatio upon him as the tide laps against the shore. ‘La Marée’ is unsettling, given Julie’s age and the way in which she is manipulated by her cousin into performing this act. (Given the casting of Fabrice Luchini, the episode feels like a perverse response to Eric Rohmer’s Le genou de Claire/Claire’s Knee, 1970.) The segment’s use of the tide as a metaphor for desire, and its examination of the intersection between desire and power (in terms of the ease with which André persuades Julie to commit this act), are characteristically Borowczyk. But they also have their roots in Mandiargues’ work. (The title of the volume in which this story appears, Mascarets, is both a term used to denote a type of current associated with the changing of the tide, and a slang word taken to refer to the moment of ejaculation.)

‘La Marée’ begins with a title card which declares, ‘Julie, my cousin, was 16, I was 20, and this small age difference made her susceptible to my authority’, before a depiction of André and Julie making preparations to cycle to the beach. Julie’s willingness to submit to the commands of André is established immediately, when André tells Julie to leave her hat in the house. She protests meekly, saying that André is wearing a hat, but he commands her to leave her own hat at home, and she obeys. The contrast between the pair is also obvious from the get-go. Where André cycles to the beach with a serious, taciturn expression on his face, Julie is carefree, singing happily; where André wears long trousers and wellington boots, Julie wears a sheer white dress over a bikini, and comfortable slip-on shoes.  At the beach, André interrogates Julie about her experiences with boys as they cross the beach, which is like an alien landscape and against which they are dwarfed by the sea and cliffs - much like the depiction of the beach on the island of Goto in Borowczyk’s first live-action picture, Goto, and strikingly similar to Jean Rollin’s use of his beach setting in Les demoniaques/Demoniacs, released the same year as Contes immoraux. André boasts, unconvincingly, of his sexual experiences with prostitutes: ‘Every Wednesday’, he says. ‘Do you kiss?’, Julie asks. ‘Not exactly’, André responds, ‘but we use their lips’. At the beach, André interrogates Julie about her experiences with boys as they cross the beach, which is like an alien landscape and against which they are dwarfed by the sea and cliffs - much like the depiction of the beach on the island of Goto in Borowczyk’s first live-action picture, Goto, and strikingly similar to Jean Rollin’s use of his beach setting in Les demoniaques/Demoniacs, released the same year as Contes immoraux. André boasts, unconvincingly, of his sexual experiences with prostitutes: ‘Every Wednesday’, he says. ‘Do you kiss?’, Julie asks. ‘Not exactly’, André responds, ‘but we use their lips’.

André is cruel to Julie. When she slips on a rock and hurts herself, he spitefully declares, ‘Watch out, brat’. Finally, as the incoming tide traps them, he tells Julie, ‘You’re going to play another game with me’. ‘I don’t mind’, Julie says in response. The rumble of the tide as it hits the shingle of the beach becomes increasingly insistent: its surge is symbolic, and the sound it makes becomes threatening, pressing, as André tells Julie that she must ‘take me in the mouth […] Like the whores at Madame Claude’s’. Whilst she does so, André promises, he will lecture her on ‘the mechanism of the tides’ which ‘rise like my desire’. Ultimately, the moment he ejaculates will be connected with the tide: ‘[Y]ou will think of this gift as being the result of the great tidal movement around us’. Reinforcing the symbolic importance of the tide, Borowczyk repeatedly cuts away to it, its ebb and flow coinciding with the act of fellatio that Julie is performing on André. When he has finished, André reminds Julie that the experience wasn’t for ‘fun’: ‘It was for your education. Now you will understand the mysteries of the tides’, he asserts.  The connections that ‘La Marée’ makes between desire and power are overt. André exploits both his position of (relative) authority and Julie’s passive nature. Julie is anticipatory of her encounter with André, willing to obey him and even desirous of him. This is communicated via metonymic close-ups of Julie’s lips (an image which adorned the film’s posters and, now, the cover of Arrow’s Blu-ray): before, during and immediately after the act of fellatio, fetishistic tight close-ups of Julie’s lips betray her reticence, then her desire, and finally her frustration when the act comes to an end and she realises her efforts will not be reciprocated, this act of exploitation perhaps functioning as a metaphor for her (and, more generally, womankind’s) experiences at the hands of men throughout her life. Meanwhile, André’s discussion of the tides during their encounter has an element of monomania to it, and to some extent (especially considering the familial relationship between André and Julie) the story recalls the work of Edgar Allan Poe, especially ‘Berenice’. (In ‘Berenice’, Poe’s narrator prepares to marry his cousin Berenice, and becomes fixated on her teeth.) The connections that ‘La Marée’ makes between desire and power are overt. André exploits both his position of (relative) authority and Julie’s passive nature. Julie is anticipatory of her encounter with André, willing to obey him and even desirous of him. This is communicated via metonymic close-ups of Julie’s lips (an image which adorned the film’s posters and, now, the cover of Arrow’s Blu-ray): before, during and immediately after the act of fellatio, fetishistic tight close-ups of Julie’s lips betray her reticence, then her desire, and finally her frustration when the act comes to an end and she realises her efforts will not be reciprocated, this act of exploitation perhaps functioning as a metaphor for her (and, more generally, womankind’s) experiences at the hands of men throughout her life. Meanwhile, André’s discussion of the tides during their encounter has an element of monomania to it, and to some extent (especially considering the familial relationship between André and Julie) the story recalls the work of Edgar Allan Poe, especially ‘Berenice’. (In ‘Berenice’, Poe’s narrator prepares to marry his cousin Berenice, and becomes fixated on her teeth.)

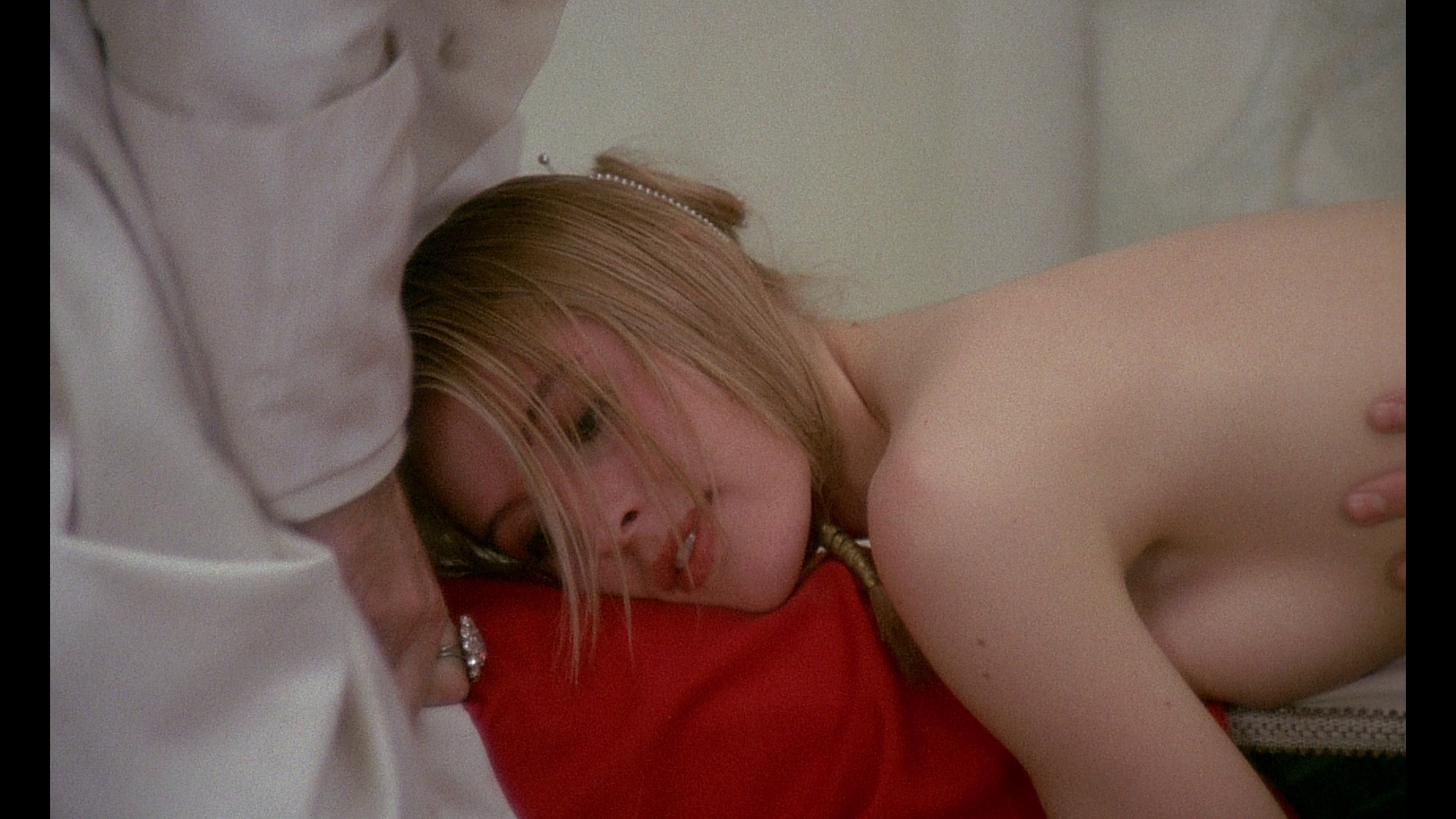

Borowczyk would return to the work of André Pieyre de Mandiargues with Le Marge (The Streetwalker, 1976), adapted from the author’s novel (of the same title), first published in 1967.  The second story, ‘Thérèse Philosophe’, was shot on 16mm, mostly with a very mobile handheld camera (in contrast to the more formal setups seen in Borowczyk’s earlier films), and features Charlotte Alexandra/Charlotte Seeley, the young-looking English-born starlet who, a year or two later, would act in Catherine Breillat’s controversial Une vraie jeune fille (A Real Young Girl, 1976). The segment begins with a title card which declares, ’10 July, 1890. The people from our region demand the beatification of Thérèse H., a pious young girl shamelessly raped by a vagrant’. The second story, ‘Thérèse Philosophe’, was shot on 16mm, mostly with a very mobile handheld camera (in contrast to the more formal setups seen in Borowczyk’s earlier films), and features Charlotte Alexandra/Charlotte Seeley, the young-looking English-born starlet who, a year or two later, would act in Catherine Breillat’s controversial Une vraie jeune fille (A Real Young Girl, 1976). The segment begins with a title card which declares, ’10 July, 1890. The people from our region demand the beatification of Thérèse H., a pious young girl shamelessly raped by a vagrant’.

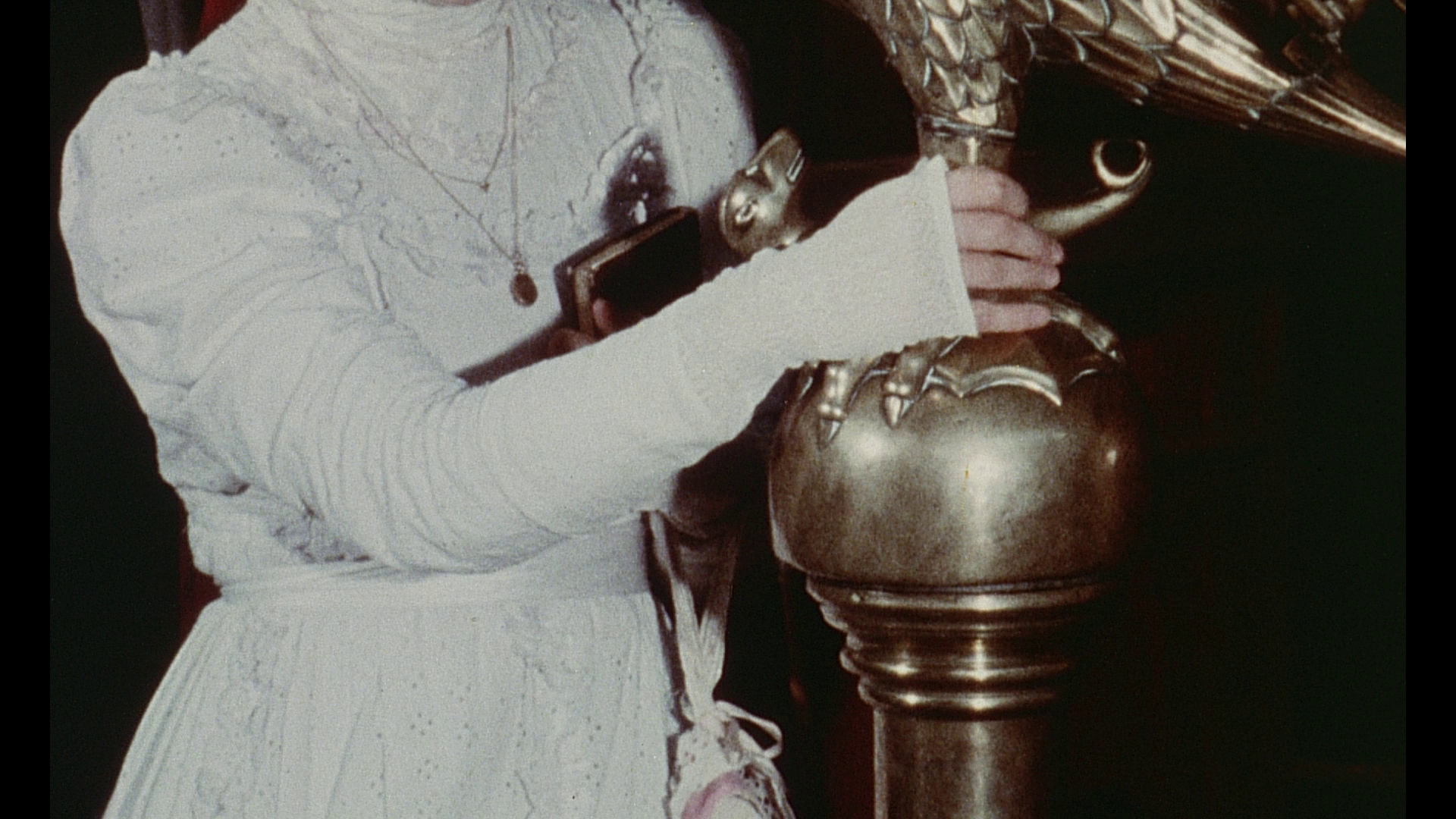

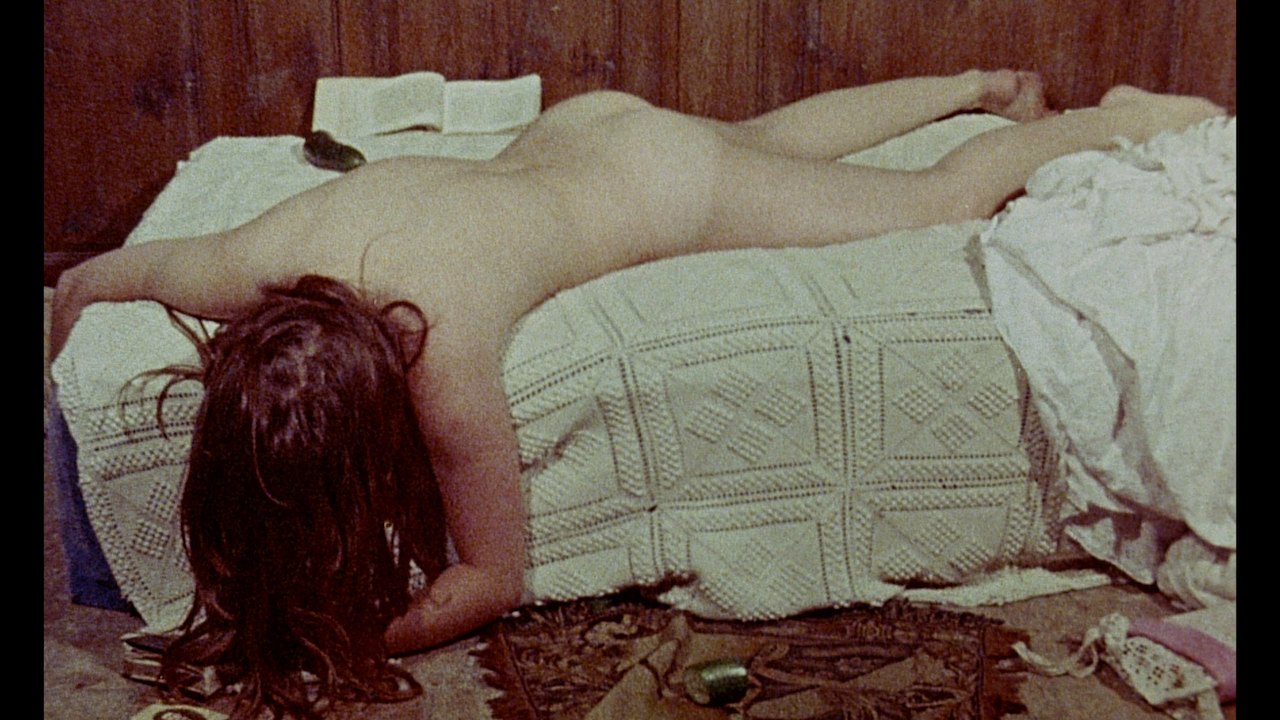

A study of religious mania and repression, the story begins with Thérèse (Alexandra) wandering through a church, lovingly caressing the religious artifacts therein (thus displaying the fetishisation of objects that is a leitmotif within Borowczyk’s work) whilst, in the form of offscreen voiceover, we hear her in an imaginary dialogue with a disembodied male voice (presumably the voice of God). For Thérèse, her love of God is associated with the sensation of touch; her journey through the church involves caressing the books, candlesticks, brassware and wood within the building, as on the audio track the male voice tells her, ‘My child, it is not necessary to be very wise to please me. It is enough to love me very much’. Returning home, Thérèse is punished by her grandmother for being late; as punishment, Thérèse is locked in her room for three days and three nights. In the room, Thérèse explores the various objects: a pince-nez, a wooden doll with a broken arm (which she kisses repeatedly, again foregrounding the theme of fetishisation of objects), erotic postcards hidden in a leather trunk (which she throws down in apparent disgust, once realising what they are). She also discovers a book, the aforementioned ‘Thérèse Philosophe’, and glances at the sexually explicit illustrations scattered throughout the volume – one of which, a satirical depiction of a Cardinal in full robes fucking a woman from behind, would work its way into the staging of the ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ segment and would also be alluded to in Interno di un convento.  Thérèse becomes agitated, and hears the disembodied voice again: He tells Thérèse that He will comfort her. Thérèse must ‘reveal’ herself by showing her ‘weakness’. Laying on the bed, Thérèse asserts, ‘I am coming for you, sweet Jesus. My heart is ready’; analepses/flashbacks show her caressing and kissing the religious paraphernalia in the church, as in the present Thérèse throws off the shackles of repression (represented through the layers of Victorian-era clothes which she wears) and, once naked, masturbates furiously – firstly with her hands and latterly with a pair of cucumbers (both of which she manages to demolish) that her grandmother presumably left in the room for sustenance. At the end of this act, satiated but apparently riddled with guilt for her transgression, Thérèse flees from the house carrying her wooden doll. However, as she crosses a field, she is followed by an elderly vagrant (who looks rather like the elderly man who continuously thwarts Mr Kabal’s voyeuristic desires in Borowczyk’s animated feature Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal, 1967). Thérèse’s fate has been tragically sealed by the title card that opens the episode. Thérèse becomes agitated, and hears the disembodied voice again: He tells Thérèse that He will comfort her. Thérèse must ‘reveal’ herself by showing her ‘weakness’. Laying on the bed, Thérèse asserts, ‘I am coming for you, sweet Jesus. My heart is ready’; analepses/flashbacks show her caressing and kissing the religious paraphernalia in the church, as in the present Thérèse throws off the shackles of repression (represented through the layers of Victorian-era clothes which she wears) and, once naked, masturbates furiously – firstly with her hands and latterly with a pair of cucumbers (both of which she manages to demolish) that her grandmother presumably left in the room for sustenance. At the end of this act, satiated but apparently riddled with guilt for her transgression, Thérèse flees from the house carrying her wooden doll. However, as she crosses a field, she is followed by an elderly vagrant (who looks rather like the elderly man who continuously thwarts Mr Kabal’s voyeuristic desires in Borowczyk’s animated feature Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal, 1967). Thérèse’s fate has been tragically sealed by the title card that opens the episode.

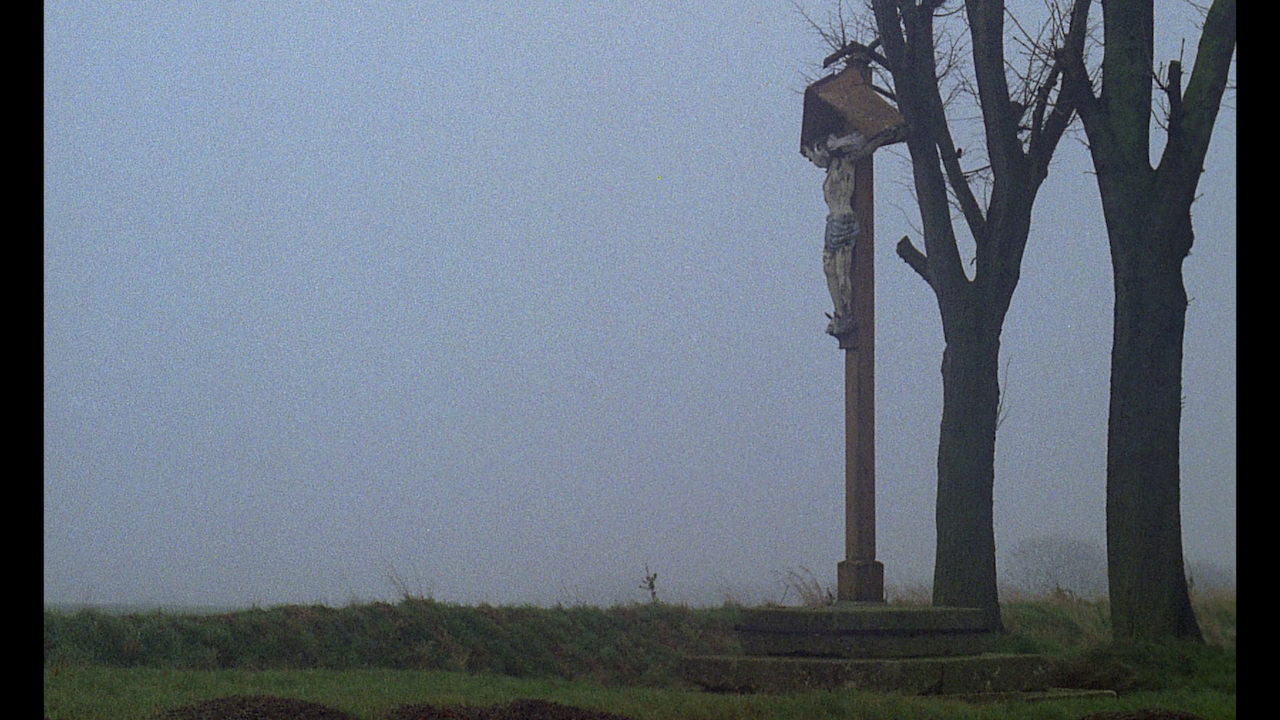

‘Thérèse Philosophe’ is an interesting episode that focuses on religious mania and sexual repression. The prolonged masturbation sequence is filmed in a way that fragments the body of Thérèse. It seems that Borowczyk used lenses with a focal length of 50mm or above for this sequence, which results in Thérèse’s body being broken down into its component/metonymic elements (hair, legs, hands, buttocks). The handheld camera emphasises the furiosity of this moment, in which Thérèse throws away the shackles of repression. The reality of Thérèse’s moment of self-exploration is juxtaposed with her memories of the church, connecting the act of masturbation with her fetishisation of the objects and textures within the church; and the tragic resolution, which Borowczyk wisely does not spell out for us (cutting away to the next segment after the camera spots the vagrant in the long grass), undercuts any potential eroticism within the masturbation sequence. Thérèse, it seems, will be punished for her transgression – but by a random act of human cruelty, rather than by an act of God.  ‘Erzsébet Báthory’ focuses on the legend surrounding Báthory, the ‘Bloody Countess’, underscoring the early-1970s fascination with this legend that was also evident in Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula (1971) and Jorge Grau’s Ceremonia sangrienta (Blood Ceremony/The Legend of Blood Castle, 1973). Borowczyk’s take on the Báthory case is based on Valentine Penrose’s Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante and, from the outset, has an ominous, foreboding air. ‘Erzsébet Báthory’ focuses on the legend surrounding Báthory, the ‘Bloody Countess’, underscoring the early-1970s fascination with this legend that was also evident in Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula (1971) and Jorge Grau’s Ceremonia sangrienta (Blood Ceremony/The Legend of Blood Castle, 1973). Borowczyk’s take on the Báthory case is based on Valentine Penrose’s Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante and, from the outset, has an ominous, foreboding air.

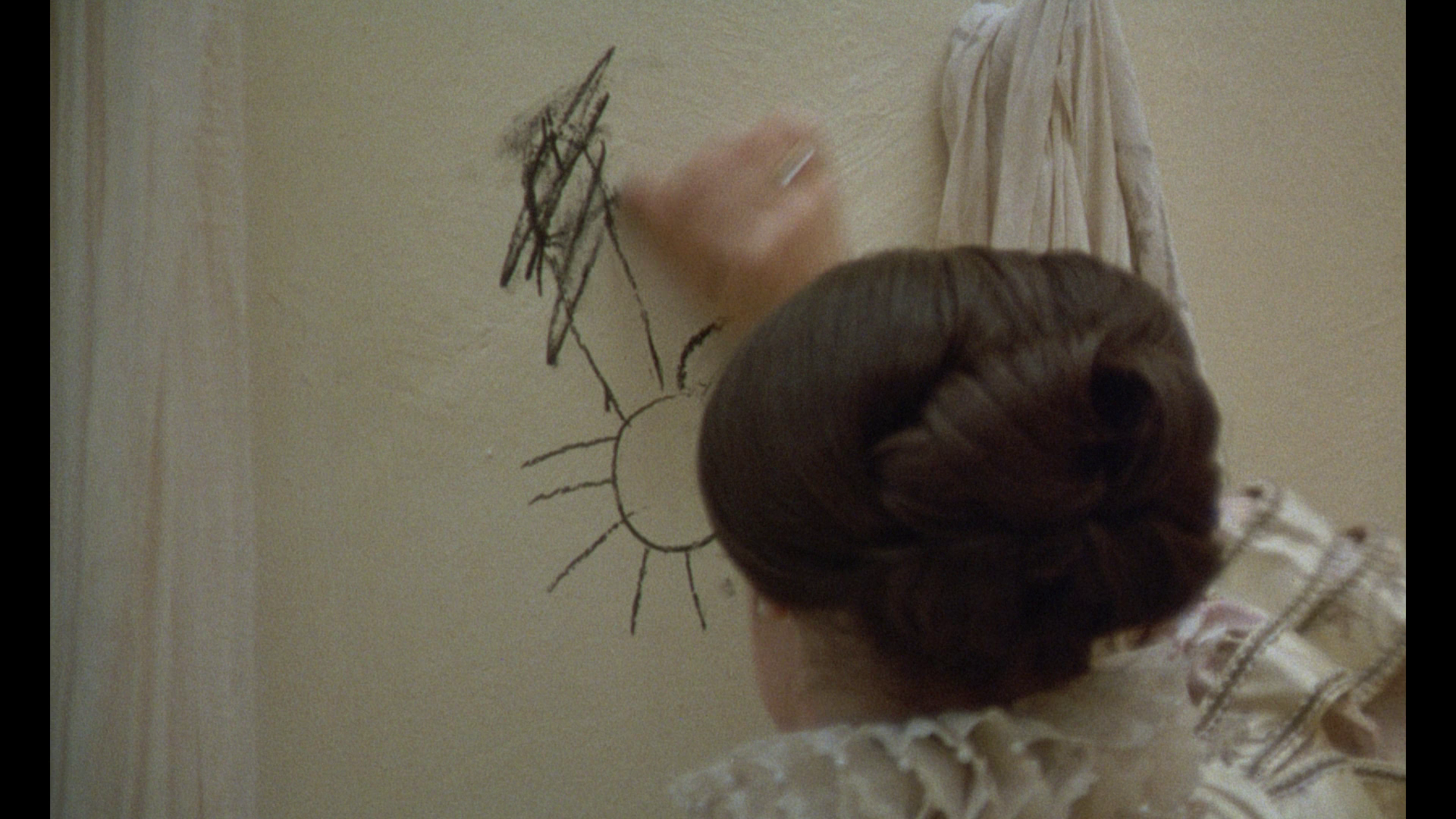

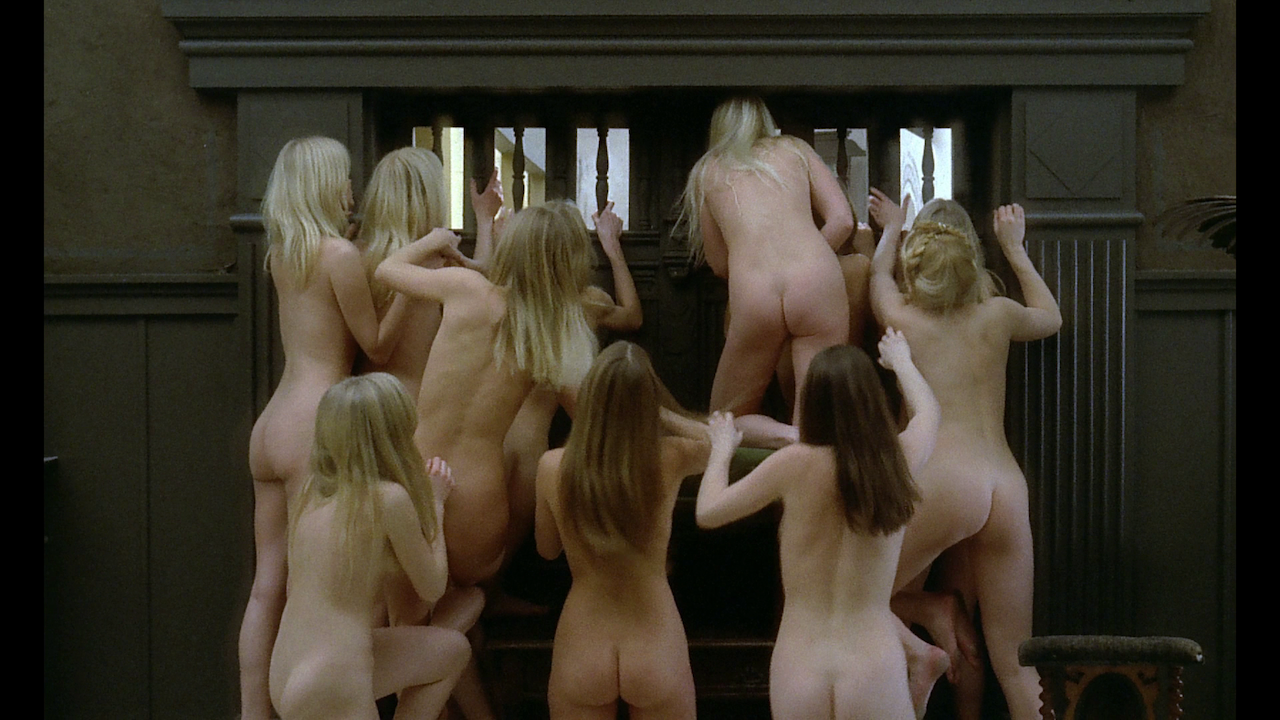

The Báthory segment features Paloma Picasso, the daughter of Pablo Picasso, as Báthory, and begins with a title card that declares, ‘In 1610, Countess Erzsébet Báthory, accompanied by a squire, visits the villages and settlements of Nyitra County in Hungary’. Following this, Borowczyk presents us with shots of Báthory and her escort riding through the countryside, filmed in profile and in long shot, showing them to be dwarfed by the landscape. Tony Thorne argues that Borowczyk’s take on the Bathory legend ‘evokes a quintessential eastern – now we should say central – European atmosphere: the claustrophobia of landlocked places and the irruption of tragedy into slow, soporific lives’ (2012: 5). Báthory and her entourage stop at a statue of the crucified Christ, situated in the middle of nowhere, around which birds flock ominously. Meanwhile, in a village a young woman is shown in flagrante delicto with her lover: they are making love on a pile of hay situated in a barn. A bell rings; the villagers hide. The feared Báthory has arrived. The village is populated almost entirely by women – and one elderly man, to whom Báthory’s soldiers address their demands, asserting that Báthory is ‘searching the countryside for honest and simple young girls’ who will be ‘paid, fed and housed better than the King himself’. Báthory, it seems, is offering ‘a great reward’ to these young women: they will be allowed to touch the Countess’ ‘miraculous gown’, which is ‘strewn with pearls’. Those who touch the gown ‘will know great joy’. More out of fear of punishment than the promise of the ‘great reward’, the young women of the village line up and are inspected by Báthory, who exposes with her riding crop their breasts and genitals. One soldier brings to Báthory a female baby, which (fortunately) is turned away by the Countess and returned to its mother. The elderly man, who seems to be the village elder, looks on, his milky eyes a signifier of his impotence within this scenario.  Relocated to the castle, the young women of the village are shown bathing in communal showers and frolicking naked through the building’s luxurious halls, a stark contrast with the poverty of their village. The girls pray in front of a statue of Christ; one girl draws on one of the walls of the communal shower a starkly modern example of vernacular art, the ubiquitous ‘bus stop cock’. Báthory and her squire Istvan (Pascale Christophe) watch the girls with an almost scientific curiosity. Relocated to the castle, the young women of the village are shown bathing in communal showers and frolicking naked through the building’s luxurious halls, a stark contrast with the poverty of their village. The girls pray in front of a statue of Christ; one girl draws on one of the walls of the communal shower a starkly modern example of vernacular art, the ubiquitous ‘bus stop cock’. Báthory and her squire Istvan (Pascale Christophe) watch the girls with an almost scientific curiosity.

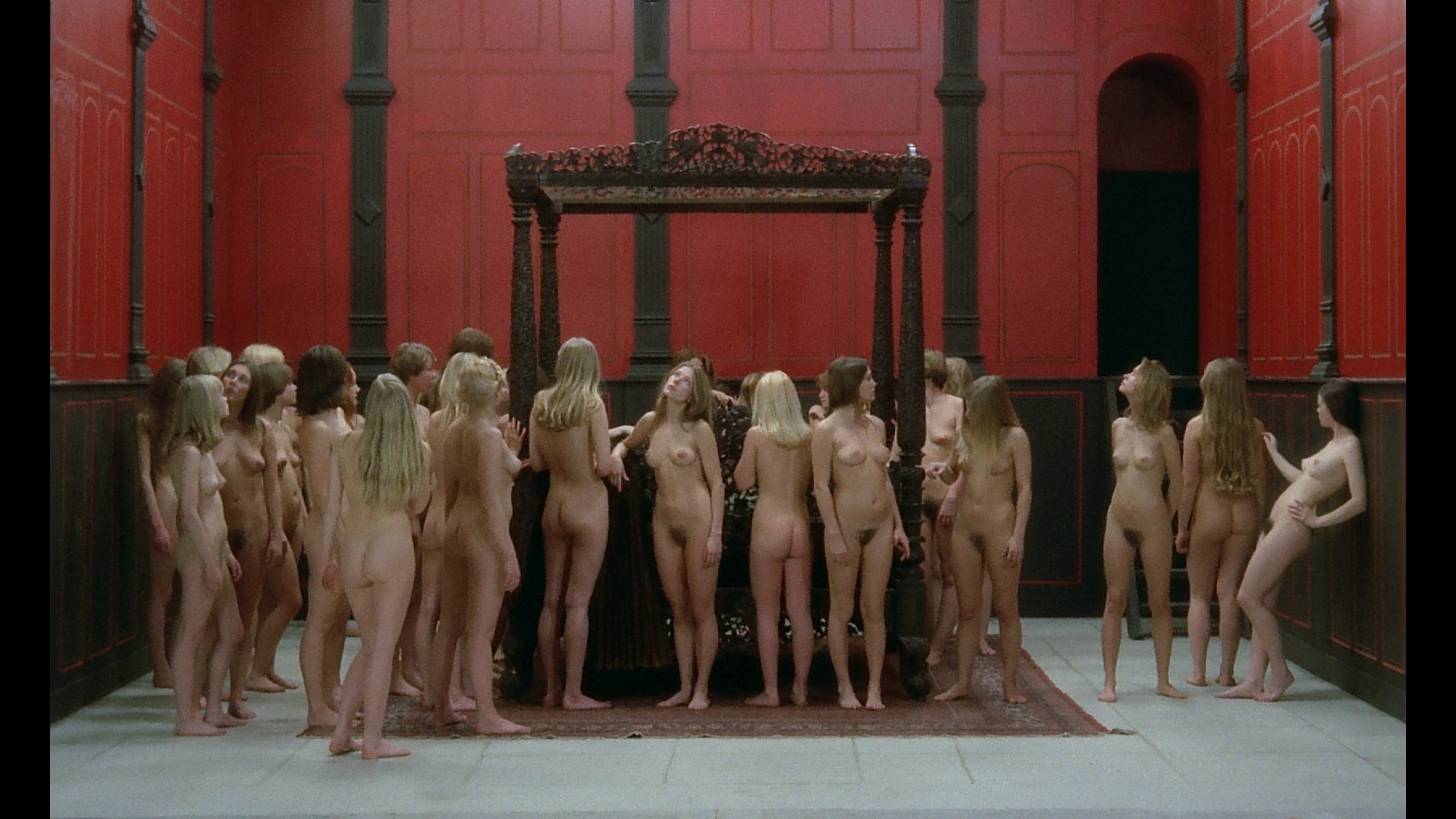

Later, Báthory has the young women gathered in a room decorated with red and black wall panels. She parades amongst the girls, wearing her dress ‘strewn with pearls’. The young women mob her, stripping the dress from her body and ripping it to shreds. They conceal the stolen pearls in any way they can: by swallowing them and, in at least one instance, inside their vaginas. The young women battle amongst themselves. Báthory is then shown bathing in the blood of the girls, who it seems have either torn themselves apart through greed or been put to the sword by Istvan. Afterwards, it is revealed that Istvan is in fact a woman (a fact that an attentive viewer would most likely have already guessed), and that she and Báthory are lovers. Istvan and Báthory sleep in the same bed. During the night, Istvan sneaks out of the room; in the morning, the King’s guards storm into Báthory’s bedchamber, telling her ‘All resistance is futile’. They arrest Báthory, and Istvan is shown kissing a young man. Unlike other films based on the legend (for example, Sasdy’s Countess Dracula), Borowczyk does not show Báthory regaining her youth through bathing in the blood of the young women. Báthory is young at the start of the segment and remains youthful at its resolution. The suggestion that Báthory was motivated by vanity (and the belief that bathing in the blood of virgins would allow her to remain youthful) was, it has been argued, added to the Báthory legend in the early 19th Century, when it seemed people were more willing to accept Báthory’s involvement in the murders of an estimated 640 young women if it was motivated by vanity than by sadism – a trait seen as antithetical to the stereotypes associated with femininity. Since then, the legend has often been used as a warning against female vanity. However, in refusing to focus on this aspect of the legend, Borowczyk highlights the sadistic element of Báthory’s bloodlust. Borowczyk foregrounds the repressive aspects of the society which allow Báthory to carry out her atrocities. When Báthory and her soldiers approach the villagers and promise the young women a ‘great reward’, the villagers are unable to refuse Báthory’s request. The soldiers direct Báthory’s request towards an elderly man, who they (and we) presume to be the representative of the inhabitants of the village (the assumption of patriarchal authority is of course inverted in the depiction of Báthory’s control over the soldiers). The elderly man’s milky eyes are shown in close-up, watching helplessly as Báthory and her soldier round up the young women and inspect them as if they were cattle at an auction. As in other examples of his work, Borowczyk foregrounds the exploitation (and objectification) of the peasant class by aristocrats; the Báthory legend would, of course, inform the representation of the vampire, in Bram Stoker’s Dracula and beyond, as an aristocratic predator who literally feeds on the blood of the peasant class. This objectification is also underscored by the shower scenes, which break down the female body into metonymic elements through close-ups of breasts, genitals, etc, as Báthory and Istvan watch the girls bathe. This particular sequence uses the iconography of similar shower scenes (watched over by lesbian wardens) associated with the women-in-prison pictures that were popular during the early/mid 1970s (for example, Jess Franco’s Frauengefängnis/Barbed Wire Dolls, 1976, or Eddie Romero’s Black Mama, White Mama, 1973).  Finally, ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ focuses on the corruption of the Borgia family, represented through their act of incest, and juxtaposes it with the persecution as a heretic of the puritan friar Hieronimo Savonarola, who was executed in 1498 after making an enemy of Pope Alexander VI for Finally, ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ focuses on the corruption of the Borgia family, represented through their act of incest, and juxtaposes it with the persecution as a heretic of the puritan friar Hieronimo Savonarola, who was executed in 1498 after making an enemy of Pope Alexander VI for

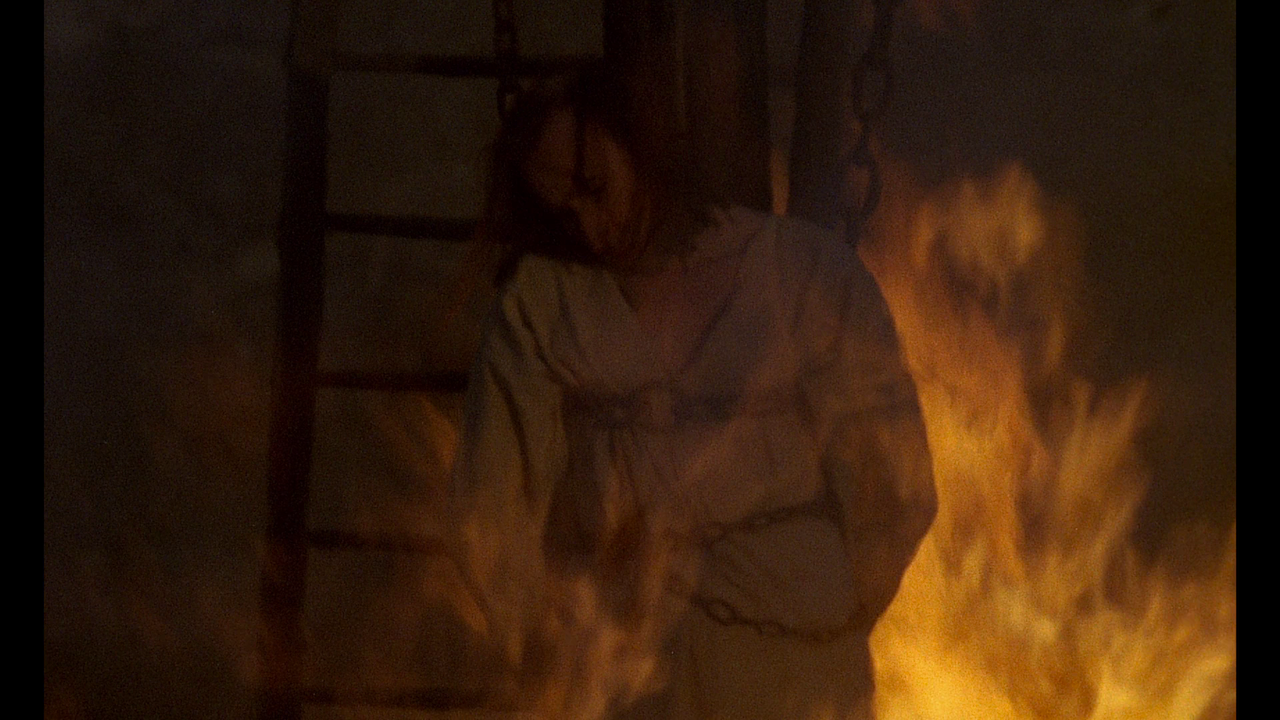

denouncing the corruption of the Catholic church. The title card for this segment announces that ‘In 1487, Lucrezia Borgia, accompanied by her husband Giovanni Sforza, visits her father, Pope Alexander VI, and brother, Cardinal Cesare Borgia. The Domenican Hyeronimo Savonarola accuses the Church hierarchy of dissolution’. Following this title card, Savonarola (Philippe Desboeuf) is shown addressing an audience from a pulpit, declaring ‘And so you, Italy’s profane church, you were once quite shameful! That the evil and lust be known! Now, today, you have set aside virtue’. With this, Borowczyk cuts pointedly to a shot of Pope Alexander VI (Mario Ruspoli) who is gazing at a statue of a bare-breasted woman riding a tiger. ‘Woman astride a tiger’, the Pope observes, ‘What breasts!’ The Pope mocks the impotence of Sforza (the first of Lucrezia Borgia’s three husbands; Sforza and Borgia’s marriage was annulled in 1497, with claims that Sforza was impotent). Sforza demonstrates his paranoia when the Pope offers him a biscuit and Sforza refuses to eat one, at least until the Pope has eaten half of it to prove that it is not poisoned. The Pope further humiliates Sforza by showing him and a conspiratorial Lucrezia (Florenze Bellamy) obscene drawings of copulating horses (imagery that would reappear in La bête), noting that ‘Lucrezia Borgia would also gladly have relations with such a beast’ whilst Cesare Borgia caresses his cock through his robes and sniggers like a schoolboy.  Soon, Sforza is seized by soldiers and Lucrezia, the Pope and the Cardinal engage in an incestuous threesome, which Borowczyk intercuts with Savonarola delivering his sermon against the corruption of the church (‘And we’re not only talking about the abuse of women and young boys’, he asserts, ‘They’re only interested in dogs and mules’). Finally, Savonarola is arrested by soldiers and, as the Borgias reach the climax of their unholy encounter, burned as a heretic. The segment ends with the baptism of a child. The child is presumably Giovanni Borgia, the ‘Infans Romanus’ who history tells us was most likely the son of either Cesare Borgia or Pope Alexander VI, and who may or may not have been the child of Lucrezia Borgia. The baby looks on, smiling innocently, at the parade of golden crucifixes on display – symbols of the church’s wealth, against which the puritan Savonarola railed. Soon, Sforza is seized by soldiers and Lucrezia, the Pope and the Cardinal engage in an incestuous threesome, which Borowczyk intercuts with Savonarola delivering his sermon against the corruption of the church (‘And we’re not only talking about the abuse of women and young boys’, he asserts, ‘They’re only interested in dogs and mules’). Finally, Savonarola is arrested by soldiers and, as the Borgias reach the climax of their unholy encounter, burned as a heretic. The segment ends with the baptism of a child. The child is presumably Giovanni Borgia, the ‘Infans Romanus’ who history tells us was most likely the son of either Cesare Borgia or Pope Alexander VI, and who may or may not have been the child of Lucrezia Borgia. The baby looks on, smiling innocently, at the parade of golden crucifixes on display – symbols of the church’s wealth, against which the puritan Savonarola railed.

This sequence makes prominent use of a handheld camera and a zoom lens, as noted by camera operator Noël Véry in the featurette about the film’s production that is included on this disc. The resulting footage, which features edits inserted into zooms and roving camerawork, has some similarities with the work of Silvano Ippoliti, the cinematographer most closely associated with the work of Giovanni ‘Tinto’ Brass. Against type, given the film’s production after Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and the spate of films it inspired (for example, Jess Franco’s Les démons, 1973), Borowczyk downplays the torture and execution of Savonarola, who, history tells us, was hanged and then burned rather than (as depicted here) burned at the stake. (Some accounts suggest that when the flames were lit beneath the gibbet holding the bodies of Savonarola and two of his friar brothers, the contraction of the muscles in Savonarola’s right arm, caused by the heat, led to the corpse appearing to bless the crowd; this is a touch that Borowczyk perhaps surprisingly chose to omit.) ‘Lucrezia Borgia’, which stresses the utter corruption of those in authority, and explores the links between sex and power, offers a fitting resolution to Contes immoraux, providing a climax of sorts to the themes explored throughout the three preceding entries. The film is uncut and runs for 103:08 mins.

Video

As with all of Arrow’s Borowczyk releases, Contes immoraux gets an enormously impressive Hi-Def presentation on this Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 25Gb of a dual-layered disc. The majority of the film was shot on 35mm negative film, barring ‘Thérèse Philosophe’, which was shot on 16mm reversal stock. Aside from having a narrower exposure latitude, the use of reversal stock (rather than negative film) requires the production of an internegative, which tends to result in an image with harsher contrast than footage shot on negative film, a slightly different tonal range, and a coarser, more defined grain structure. Consequently, ‘Thérèse Philosophe’ looks strikingly different from the other three segments within Contes immoraux, and the strong encode on this disc handles the different ‘texture’ of this segment superbly, with the result that the film throughout has a natural, organic-looking presentation. NB. Larger screen grabs from all four segments are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track, which displays excellent range, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles. (Incidentally, the subtitles for the title cards are presented on a ‘ghost boxed’ background to make them easier to read.)

Extras

The disc includes the following contextual material: Immoral Tales: The L’Age d’Or Cut (125:25). This is a longer version of the film that includes ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’. The complete version of this segment, shot on 16mm (and therefore similar in appearance to ‘Thérèse Philosophe’), was rediscovered in 2010: prior to that, only the footage from this segment that was used in La bête was thought to be in existence. Introduction by Borowczyk expert Daniel Bird (5:14). This introduction to the film comprises text intercut with still and moving images. 'Love Reveals Itself: Making Immoral Tales' (16:42). Focusing on the production of Contes immoraux, this fascinating featurette features input from producer Dominique Duvergé-Ségrétin and camera operator Noël Véry. Duvergé-Ségrétin discusses the position of Contex immoraux within Borowczyk’s body of work, arguing that rather than representing a departure from the earlier films, Contes immoraux highlighted the erotic content that had always been present within Borowczyk’s films. Discussing this eroticism, Noël Véry argues that it was a ‘political’ and ‘revolutionary’ eroticism that was used by Borowczyk as ‘a means to convey his fight against power and the church’. As may be evident from the discussion of Contes immoraux above, the film was shot in a different way to Borowczyk’s other films. The shots of Julie and Andre bicycling in ‘The Tide’, for example, were achieved by Véry shooting with a handheld camera through the window of a car. At the behest of Borowczyk, Véry also began to abandon the telephoto lenses previously preferred by Borowczyk and use more zoom lenses (the use of zooms is particularly noticeable within the ‘Lucrezia Borgia’ segment). Véry also developed his own Steadicam-style camera mount, nicknamed ‘the plane’, which would also go on to be used in the production of La bête. Bernard Daillencourt replaced Guy Durban as Borowczyk’s cinematographer on the Bathory segment, and Véry praises Daillencourt’s ability to light Borowzyk’s films, highlighting aspects of the décor and makeup in subtle ways. Duvergé-Ségrétin discusses Borowczyk’s attempts to find new acting talent, enlisting the help of Duvergé-Ségrétin to do so; the ‘discoveries’ made by Borowczyk during this film included Sirpa Lane (who appeared in ‘La véritable histoire de la bête du Gévaudan’), Florence Bellamy (‘Lucrezia Borgia’) and Paloma Picasso (‘Erzsébet Báthory’). Charlotte Alexandra (‘Thérèse Philosophe’), for example, worked for the modeling company Elite – but as an operator rather than a model. Interestingly, Isabelle Adjani was approached to play Julie in ‘The Tide’ but turned the role down as being ‘too difficult’; had she taken the part, Duvergé-Ségrétin suggests it would have been 'her first role in cinema'). (This isn’t strictly true: Adjani’s feature film debut was in Bernard T Michel’s Le petit bougnat, 1970, but Duvergé-Ségrétin seems to be suggesting that Contes immoraux would have offered a ‘breakout’ role for the young actress.) Duvergé-Ségrétin reveals that the bath of blood in the Báthory segment contained real animal blood, which Véry claims was, after the shooting, used by the crew to create black pudding. 'Boro Brunch: Crew Reunion' (7:36). This is, as the title suggests, a reunion of several members of the crew involved in the production of Contes immoraux: Noël Véry, Dominique Duvergé-Ségrétin, Florence Dauman, Philippe D’Argila, Dominique Ruspoli and Zoe Zurstrassen. 'A Private Collection' (1973) (12:12). Jonathan Owen has adroitly described this short film as ‘a short study of antique curios that commenced Borowczyk’s foray into explicit cinema’ (2014: 113). Borowczyk’s camera examines some bizarre erotic ephemera: photographs, drawings, mechanical contraptions. Borowczyk’s coverage of these curious objects, Owen argues, ‘emphasis[es] how these mechanisms conceal, obfuscate and gradually disclose their “shameful” erotic contents’ (2014: 113). 'A Private Collection: Oberhausen Cut' (1973) (14:31). This is an alternate edit of ‘A Private Collection’. Considerably more graphic than the shorter version, which obscures some of the more contentious imagery behind carefully-placed thumbs, the ‘Oberhausen cut’ also lacks narration. (Note that the Oberhausen version of 'A Private Collection' has been briefly censored, by around 30 seconds, in order to comply with current legislation regarding 'extreme' pornography, the possession of which is defined as an offense - as outlined by Section 63 of the 2008 Criminal Justice and Immigration Act - which meant that the footage could not even be submitted to the BBFC for consideration.)

Overall

Daniel Bird has argued that after Immoral Tales and, particularly, Interno di un convento (Behind Convent Walls, 1978), critics of Borowczyk would ‘only see the skin of his work and not the substance, the façade rather than the flesh’ (Bird, 2011: np). Contes immoraux is often cited as marking a cutoff point in Borowczyk’s work, between the more ‘mannered’ pictures that preceded it and the more overtly ‘erotic’ films that followed. However, as I’ve hopefully outlined in the above discussion of Contes immoraux, each of the segments explores the intersection between power, desire and repression – core themes within Borowczyk’s earlier films and within his body of work as a whole. However, Contes immoraux marked a turning point in terms of how Borowczyk expressed these themes, not just in terms of explicit content but in terms of the photographic techniques he deployed. With this film, Borowczyk broke away from the more painterly compositions of his earlier films (a mostly static camera, which used telephoto lenses to flatten perspective, resulting in images that had the appearance of tableaux – or, in the case of Blanche, Medieval tapestries), here adopting the use of handheld cameras and also demonstrating the use of zoom lenses – both of which would in subsequent films become a core part of Borowczyk’s cinematic ‘toolkit’. Daniel Bird has argued that after Immoral Tales and, particularly, Interno di un convento (Behind Convent Walls, 1978), critics of Borowczyk would ‘only see the skin of his work and not the substance, the façade rather than the flesh’ (Bird, 2011: np). Contes immoraux is often cited as marking a cutoff point in Borowczyk’s work, between the more ‘mannered’ pictures that preceded it and the more overtly ‘erotic’ films that followed. However, as I’ve hopefully outlined in the above discussion of Contes immoraux, each of the segments explores the intersection between power, desire and repression – core themes within Borowczyk’s earlier films and within his body of work as a whole. However, Contes immoraux marked a turning point in terms of how Borowczyk expressed these themes, not just in terms of explicit content but in terms of the photographic techniques he deployed. With this film, Borowczyk broke away from the more painterly compositions of his earlier films (a mostly static camera, which used telephoto lenses to flatten perspective, resulting in images that had the appearance of tableaux – or, in the case of Blanche, Medieval tapestries), here adopting the use of handheld cameras and also demonstrating the use of zoom lenses – both of which would in subsequent films become a core part of Borowczyk’s cinematic ‘toolkit’.

Contes immoraux is a fascinating film, which gets a first-class presentation from Arrow. Taken together, Arrow’s Borowczyk discs (whether bought as part of the Camera Obscura set or purchased alone) are some of the most significant home video releases of the year, with first class presentations and some excellent contextual material. With luck, some of Borowczyk’s later films will get a similar treatment. References: Bird, Daniel, 2011: ‘Walerian Borowczyk’. In: Bingham, Adam (ed), 2011: Directory of World Cinema, Volume 8. London: Intellect Books Goddard, Michael, 2012: ‘The Impossible Polish New Wave and its Accursed Émigré Auteurs: Borowczyk, Polanski, Skolimowski, and Zulawski’. In: Imre, Anikó (ed), 2012: The Wiley-Blackwell Companions to National Cinemas: A Companion to Eastern European Cinemas. London: Wiley-Blackwell: 291-311 Mackenzie, Robin, 2000: ‘Space, Self and the Role of the Matecznik in Merimee’s Lokis’. Forum for Modern Language Studies (XXXVI)2: 196-208 Owen, Jonathan L, 2014: ‘Avant-Garde Highlights: The Cultural Highs and Lows of Polish Émigré Cinema’. In: Kuc, Kamila (ed), 2014: 93-116 Richardson, Michael, 2006: Surrealism and Cinema. Oxford: Berg Simon, John, 1976: ‘Robin Hood and His Merry Menopause’. New York Magazine (29 March, 1976): 80-2 Thorne, Tony, 2012: Countess Dracula: The Life and Times of Elisabeth Bathory, the Blood Countess. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Screengrabs: ‘La Marée’

‘Thérèse Philosophe’

‘Erzsébet Báthory’

‘Lucrezia Borgia’

|

|||||

|