|

|

Countess Dracula (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th September 2014). |

|

The Film

Countess Dracula (Peter Sasdy, 1971)  Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula opens with Imre Toth (Sandor Elès), a lieutenant in the Hungarian army, riding towards Čachtice Castle for the funeral of his father’s friend, Count Ferenc Nádasdy. He is late, however, and on the way to the castle he spots the funeral and stops to join it, attracting the attention of Countess Elisabeth Bathory (Ingrid Pitt). At the reading of the Count’s will, Toth is left the stable and horses, anchoring him to the castle. Meanwhile, the castle steward, Captain Dobi (Nigel Green), is left nothing. Already resentful of Toth, Dobi becomes even more displeased with the handsome young man’s presence when it becomes clear that Toth has attracted the amorous attentions of the Countess, with whom Dobi has been in love for twenty years. Meanwhile, the Count and Countess’ daughter Ilona (Lesley-Anne Down) is on her way to the castle, late for her father’s funeral and also late for the reading of his will. Peter Sasdy’s Countess Dracula opens with Imre Toth (Sandor Elès), a lieutenant in the Hungarian army, riding towards Čachtice Castle for the funeral of his father’s friend, Count Ferenc Nádasdy. He is late, however, and on the way to the castle he spots the funeral and stops to join it, attracting the attention of Countess Elisabeth Bathory (Ingrid Pitt). At the reading of the Count’s will, Toth is left the stable and horses, anchoring him to the castle. Meanwhile, the castle steward, Captain Dobi (Nigel Green), is left nothing. Already resentful of Toth, Dobi becomes even more displeased with the handsome young man’s presence when it becomes clear that Toth has attracted the amorous attentions of the Countess, with whom Dobi has been in love for twenty years. Meanwhile, the Count and Countess’ daughter Ilona (Lesley-Anne Down) is on her way to the castle, late for her father’s funeral and also late for the reading of his will.

After cruelly striking her chambermaid for filling her bath with water that is too hot, the Countess finds her face splashed with the girl’s blood. She is surprised to discover that the blood of the chambermaid reverses the aging process, making the Countess appear youthful once more. The Countess demands that the chambermaid be brought to her chambers; the girl disappears, but Dobi and the Countess’ nurse Julie discover the Countess now appears to be thirty years younger. It doesn’t take long for them to surmise that the Countess has killed the servant girl.  The Countess soon begins to masquerade as her own daughter in an attempt to seduce Toth. She commissions Dobi with the task of capturing the real Ilona before she arrives at the castle. However, she discovers that the effect of the servant girl’s blood is only temporary: she must need a constant supply of the blood of virgins to remain youthful. And each time she returns to her real age, she becomes increasingly unhinged. Soon, Toth begins to suspect her real nature, and the Countess’ allies (Dobi and Julie) become increasingly alienated by her. Meanwhile, the villagers begin to discover the bodies of the young women that Bathory has had slaughtered. The Countess soon begins to masquerade as her own daughter in an attempt to seduce Toth. She commissions Dobi with the task of capturing the real Ilona before she arrives at the castle. However, she discovers that the effect of the servant girl’s blood is only temporary: she must need a constant supply of the blood of virgins to remain youthful. And each time she returns to her real age, she becomes increasingly unhinged. Soon, Toth begins to suspect her real nature, and the Countess’ allies (Dobi and Julie) become increasingly alienated by her. Meanwhile, the villagers begin to discover the bodies of the young women that Bathory has had slaughtered.

Interest in the legend surrounding Elisabeth Bathory, the ‘Bloody Countess’, seemed to pique during the early 1970s, with a number of films based on the mythology that surrounds her – either using the legend as the basis for their narrative or building a new story around its principal elements. Walerian Borowczyk included a segment based on Bathory (‘Erzsébet Báthory’) in his portmanteau film Contes immoraux (Immoral Tales, 1974); and the Spanish filmmaker Jorge Grau made a feature focusing on the Bathory legend, Ceremonia sangrienta (Bloody Ceremony / The Legend of Blood Castle), in 1974. The first of this wave of films to reference Bathory was Franco Brocani’s oddball art picture Necropolis (1970), in which the Bathory character (renamed ‘Marthory’) was played by Warhol ‘superstar’ Viva. The legend of Bathory is referenced in one way or another in several Paul Naschy films of the period, including La noche de Walpurgis (The Werewolf Versus the Vampire Woman, León Klimovsky, 1971), where the Bathory character is given the name Countess Wandessa and played by Patty Shepard, and El retorno de Walpurgis (Curse of the Devil, Carlos Aured, 1973), in which in the film’s opening sequence Irineus Daninsky (Naschy) executes Bathory (Maria Silva) and she places a curse on his family line, one which turns them into werewolves. One of the most interesting of these films is perhaps Harry Kümel’s Les lèvres rouges (Daughters of Darkness, 1971), which transplants the Bathory legend to present-day Ostend.  Interest in the Bathory legend coincided with increasingly relaxed ideas about the depiction of sex and violence on the screen, and relaxation in approaches to film censorship in many countries. The Bathory legend offered opportunities for (or, arguably, necessitated) an increasing emphasis on female nudity and gore: part of the recurring iconography throughout a number of these films is the image of a nude Bathory (or Bathory stand-in) bathing in the blood of slaughtered young women. In some of the films, Bathory is depicted as a vampire (of the blood-drinking variety): this is the case in Kümel’s Les lèvres rouges, for example. Interest in the Bathory legend coincided with increasingly relaxed ideas about the depiction of sex and violence on the screen, and relaxation in approaches to film censorship in many countries. The Bathory legend offered opportunities for (or, arguably, necessitated) an increasing emphasis on female nudity and gore: part of the recurring iconography throughout a number of these films is the image of a nude Bathory (or Bathory stand-in) bathing in the blood of slaughtered young women. In some of the films, Bathory is depicted as a vampire (of the blood-drinking variety): this is the case in Kümel’s Les lèvres rouges, for example.

Coming early in this cycle, Countess Dracula was the first film about Bathory to refer to the character by the name of Bathory. Prior to the production of Countess Dracula, Hammer had already diversified into films about female vampires, often referencing Sheridan Le Fanu’s novel Carmilla (1872), with pictures like The Vampire Lovers (Roy Ward Baker, 1970), Lust for a Vampire (Jimmy Sangster, 1971) and Twins of Evil (John Hough, 1971), exploring the sensationalistic possibilities of the concept of a female bloodsucker: however, in these films (as in Kümel’s Les lèvres rouges), the female vampire is usually coded as a lesbian, and homosexuality is conflated with female narcissism and vampirism as a signifier of deviance. Jess Franco would stretch the pornographic possibilities of both the lesbian vampire and Bathory-inspired films to their extreme in La comtesse aux seis nus (The Bare Breasted Countess / Female Vampire, 1973), and especially its hardcore variant Les avaleuses (Erotikill), in which Lina Romay plays the Countess Irina von Karlstein, whose curious brand of vampirism involves absorbing the life force of her (both male and female) victims by performing oral sex upon them. Sandor Eles, who played the role of Imre Toth in Countess Dracula, once noted that he ‘suspected while making it that the film didn’t have a great deal to do with the real-life Elizabeth Bathory, but I think back then we all realised that even if she had not bathed naked in the blood of virgins to preserve her youth […], that colourful legend was the most interesting thing about her. Sex and horror – a surefire combination, right?’ (quoted in Forshaw, 2013: 194). In fact, Eles suggests that Pitt told him she felt the film should have been more outrageous than it was: ‘what could have been one of the most outrageous Hammer films’, especially given the subject matter, ‘actually comes across as rather restrained’ (Eles, quoted in ibid.: 195).  Both the producer (Alexander Paal) and director (Peter Sasdy) of Countess Dracula were expatriate Hungarians. The script was also claimed to have some basis in the research of Hungarian author Gabriel Ronay, who would write about Bathory in his 1972 book The Dracula Myth. The film’s title highlights the parallels that are often drawn between Bathory and Bram Stoker’s creation: both originate in the Carpathians and are feared by the inhabitants of the local villages as monsters; and for both, the blood of (predominantly female and innocent) victims is necessary to maintain an appearance of eternal youth. (In the book Dracula was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania, 1983, Raymond McNally claims that Stoker’s Dracula was inspired as much by Bathory, whose legend Stoker had apparently encountered in Sabine Baring-Gould’s 1965 volume The Book of Were-Wolves, as it was by Vlad Dracul.) Both the producer (Alexander Paal) and director (Peter Sasdy) of Countess Dracula were expatriate Hungarians. The script was also claimed to have some basis in the research of Hungarian author Gabriel Ronay, who would write about Bathory in his 1972 book The Dracula Myth. The film’s title highlights the parallels that are often drawn between Bathory and Bram Stoker’s creation: both originate in the Carpathians and are feared by the inhabitants of the local villages as monsters; and for both, the blood of (predominantly female and innocent) victims is necessary to maintain an appearance of eternal youth. (In the book Dracula was a Woman: In Search of the Blood Countess of Transylvania, 1983, Raymond McNally claims that Stoker’s Dracula was inspired as much by Bathory, whose legend Stoker had apparently encountered in Sabine Baring-Gould’s 1965 volume The Book of Were-Wolves, as it was by Vlad Dracul.)

The real Bathory was accused of torturing and murdering approximately 80 young women and girls between 1585 and 1610. (Though an unverified source, said to be Bathory’s diary, suggested she may have claimed around 640 victims.) When she was arrested, her cruelty was evidenced in the corpses and survivors of her brutal regime that were discovered in her home in Csejthe Manor, the manor house within Čachtice Castle. Bathory’s cruelty extended to beating her maids and torturing them with red hot irons, and pouring boiling water upon them whilst they were seated in an earthenware tank. When she was arrested, Bathory was also accused of cannibalism. Bathory was arrested in 1610, after rumours about her had circulated for around a decade, by György Thurzó, the Palatine of Hungary. Bathory’s husband, Count Ferenc Nádasdy, died of an unknown illness in 1604, after having served during the Ottoman-Hungarian wars; Nádasdy developed a reputation for cruelty, and was also known for impaling his enemies (much like Vlad Dracul), and it has been suggested that Nádasdy taught his wife methods of torture as a means of enabling her to maintain discipline amongst the castle’s staff whilst he was absent. Before he died, Nádasdy entrusted Thurzó with caring for his wife and children. (Thurzó had a son, Imre Thurzó, possibly the inspiration for the character of Imre Toth in Countess Dracula.) Thurzó apparently managed to persuade King Mattias that Bathory should remain under house arrest rather than be executed for her crimes. (Four of Bathory’s servants were accused of conspiring with her; three of these were executed, and a fourth was given a sentence of life imprisonment.) Bathory remained in the castle, in a set of chambers that was entirely bricked up save for small slits through which food could be passed, until she died, rather undramatically, in 1614.  The suggestion that Bathory either bathed in or drank the blood of virgins in order to retain a youthful appearance was added much later, in a 1729 account by László Turóczi, Tragica Historia, and consolidated by Matthias Bel’s 1742 Burg und Stadt Csejte. Numerous subsequent sources, both fictional stories and non-fiction accounts of Bathory’s activities, referred to Bathory’s bathing in blood (for a full list, see Kord, 2009: 62). Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s story ‘Eternal Youth, 1611’ added to the legend the even more outlandish device of an Iron Maiden that was used as a ‘blood press’. The suggestion that Bathory either bathed in or drank the blood of virgins in order to retain a youthful appearance was added much later, in a 1729 account by László Turóczi, Tragica Historia, and consolidated by Matthias Bel’s 1742 Burg und Stadt Csejte. Numerous subsequent sources, both fictional stories and non-fiction accounts of Bathory’s activities, referred to Bathory’s bathing in blood (for a full list, see Kord, 2009: 62). Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s story ‘Eternal Youth, 1611’ added to the legend the even more outlandish device of an Iron Maiden that was used as a ‘blood press’.

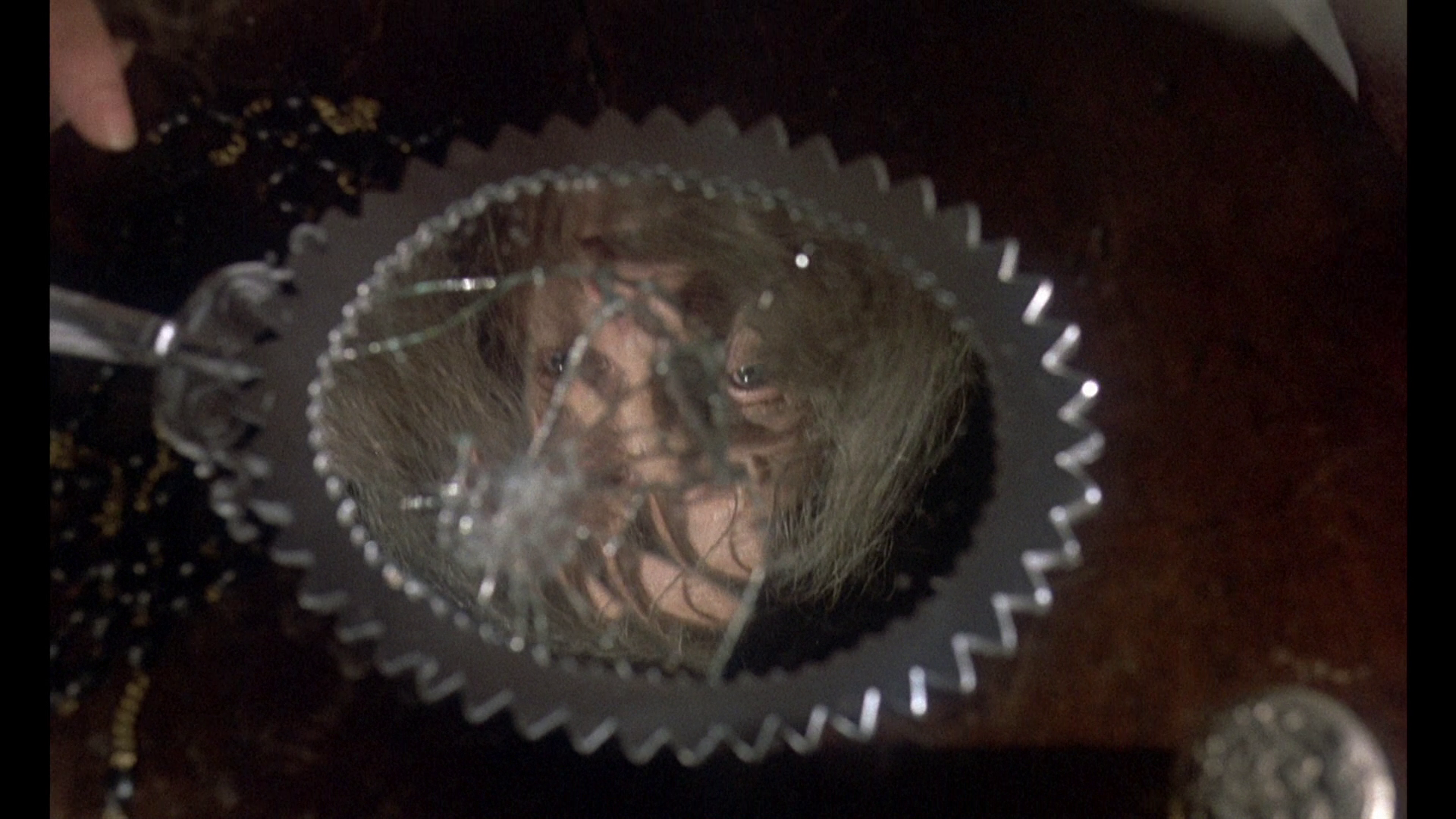

Interestingly, Bathory was at the time claimed to have tortured and killed both young women of noble birth and peasants – though the majority of the films that focus on her, including Countess Dracula, focus exclusively on the notion that Bathory preyed upon the peasant class, reinforcing one of the central metaphors within Stoker’s Dracula, that the ‘vampire’ (loosely-defined) is an aristocrat that literally feeds off the proletariat. Within Countess Dracula, the relationship between the aristocratic characters and the rural peasants is foregrounded in the opening sequence when, riding back from the Count’s funeral, a village man grabs hold of the Countess’ carriage, hanging on. The man pleads with the Countess: ‘Your husband promised me work’, he tells her. Dobi lashes the man’s hands with his whip; the peasant falls and is crushed by the wheel of the carriage. Sasdy cuts to a peasant woman who, watching this, asserts, ‘Devil woman! Devil! Devil!’ Later, Toth and Dobi enter an inn together. As they enter, the inn falls silent and the villagers eye the pair. ‘Why do they stare at us?’, Toth asks. ‘Fear’, Dobi answers. ‘Fear of what?’, Toth asks. ‘As a dog fears its master’, Dobi tells him.  The conflict between aristocrat and peasant is not the only dualism within the interpretation of the Bathory legend that is outlined in Sasdy’s film. Here, age is also pitted against youth: Bathory is in constant need of blood so that she may masquerade as her young daughter, Ilona, in order to satiate her desire for the handsome Imre Toth. However, this romantic plot has a doubling within the narrative, in terms of Dobi’s unrequited desire for Bathory: Dobi tells Bathory that he has loved her for over twenty years, and is frustrated when the death of her husband, the Count, does not result in Bathory seeing Dobi as a potential husband. Dobi foregrounds the film’s dualistic approach to age when he tells Bathory – who, having returned to her ‘true’ age, the effects of the blood bath wearing off, is shamed when she catches sight of herself in a mirror – ‘I’d rather have you as you are than see you parading yourself like some jaded young slut from the whorehouse. There’s dignity in age’. The conflict between aristocrat and peasant is not the only dualism within the interpretation of the Bathory legend that is outlined in Sasdy’s film. Here, age is also pitted against youth: Bathory is in constant need of blood so that she may masquerade as her young daughter, Ilona, in order to satiate her desire for the handsome Imre Toth. However, this romantic plot has a doubling within the narrative, in terms of Dobi’s unrequited desire for Bathory: Dobi tells Bathory that he has loved her for over twenty years, and is frustrated when the death of her husband, the Count, does not result in Bathory seeing Dobi as a potential husband. Dobi foregrounds the film’s dualistic approach to age when he tells Bathory – who, having returned to her ‘true’ age, the effects of the blood bath wearing off, is shamed when she catches sight of herself in a mirror – ‘I’d rather have you as you are than see you parading yourself like some jaded young slut from the whorehouse. There’s dignity in age’.

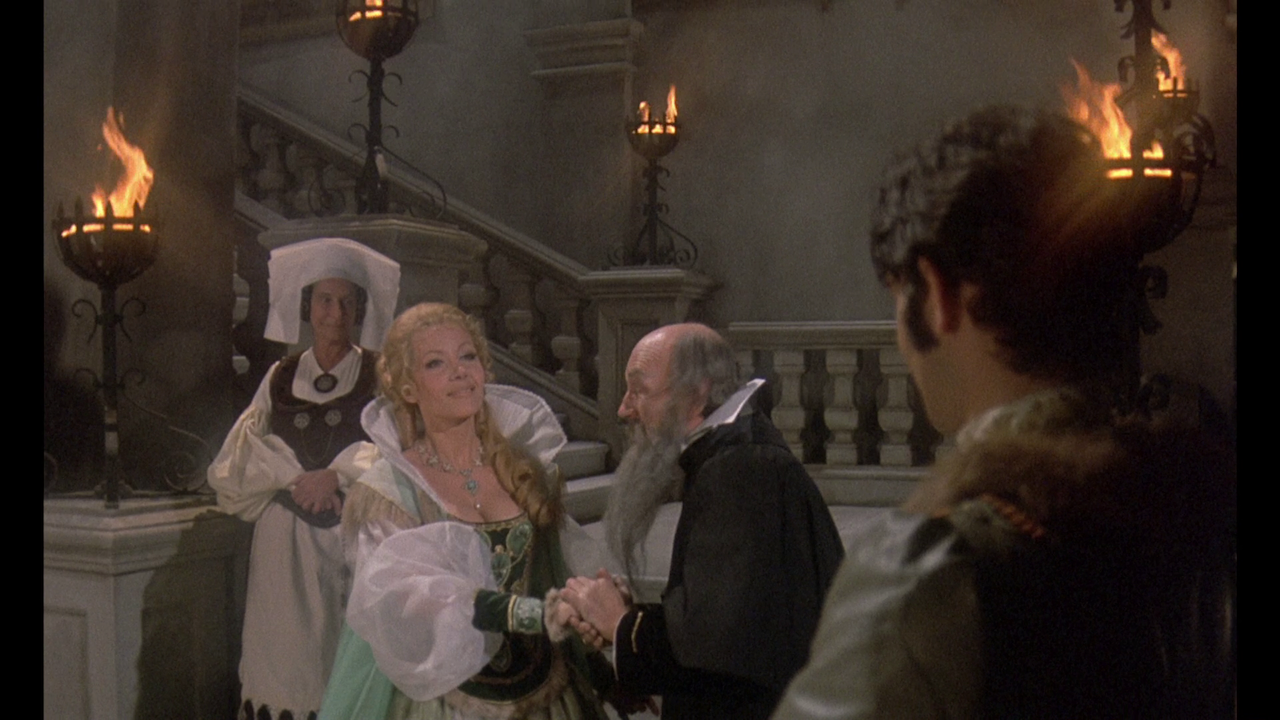

A strength of the film is Pitt’s performance as Bathory, a woman obsessed with the idea of control and riddled with vanity. In her first public appearance as Ilona, to the other guests within the castle, the Countess deliberately humiliates Dobi by reflecting on a ‘memory’ from her/Ilona’s childhood in which she claims she caught her mother in flagrante delicto with the castle steward. Bathory is depicted as representing a challenge to male authority in her control over the castle and its inhabitants. In the opening sequence, for example, Bathory is in control of the typically male gaze, looking upon Imre with desire (see Hutchings, 1993: 169). Where women are traditionally those who are the objects of the male gaze, here Bathory is in control of the gaze and Toth is objectified by it.  Peter Hutchings has argued that as the film’s narrative progresses, Bathory’s gaze ‘and the desire it signals, is increasingly identified as a transgression against patriarchal definitions of the feminine which are seen to be founded on a double-standard opposition between virgin and whore’ (ibid.). In one scene, Dobi actually extends the Madonna/whore dualism into a perverse trinity of virgin, whore and mother. When Toth asks Dobi why he has never married, Dobi responds: ‘Why should a man be a slave to one women when he can have the pick of any’. ‘Oh, but if that woman embodies all virtue…’, Toth begins. ‘Mistress, slave and mother in one? Does such a woman exist?’ Hutchings argues that within the film, Bathory comes to represent a pre-Oedipal mother (ibid.). However, the dialogue above introduces an Oedipal subtext that comes to the foreground when, later in the film, Bathory begins to refer to Toth, who at this point is her lover, as ‘son’. At one point, an unknowing Toth visits the ‘elderly’ Bathory to ask for the hand in marriage of the woman he believes to be Ilona. ‘Come to me, my son’, Bathory says. Later, the ‘youthful’ Bathory, masquerading as Ilona, also refers to Toth as ‘son’. Peter Hutchings has argued that as the film’s narrative progresses, Bathory’s gaze ‘and the desire it signals, is increasingly identified as a transgression against patriarchal definitions of the feminine which are seen to be founded on a double-standard opposition between virgin and whore’ (ibid.). In one scene, Dobi actually extends the Madonna/whore dualism into a perverse trinity of virgin, whore and mother. When Toth asks Dobi why he has never married, Dobi responds: ‘Why should a man be a slave to one women when he can have the pick of any’. ‘Oh, but if that woman embodies all virtue…’, Toth begins. ‘Mistress, slave and mother in one? Does such a woman exist?’ Hutchings argues that within the film, Bathory comes to represent a pre-Oedipal mother (ibid.). However, the dialogue above introduces an Oedipal subtext that comes to the foreground when, later in the film, Bathory begins to refer to Toth, who at this point is her lover, as ‘son’. At one point, an unknowing Toth visits the ‘elderly’ Bathory to ask for the hand in marriage of the woman he believes to be Ilona. ‘Come to me, my son’, Bathory says. Later, the ‘youthful’ Bathory, masquerading as Ilona, also refers to Toth as ‘son’.

It’s interesting to revisit this film shortly after reviewing Walerian Borowczyk’s Contes Immoraux and its retelling of the Bathory legend in its third segment, ‘Erzsébet Báthory’. Borowczyk’s take on the mythology surrounding Bathory downplays the vanity of Bathory (the suggestion that bathing in the blood of virgins restored her youth), an aspect of the Bathory legend which seems to have been added in the early 19th Century, when it seemed people were more willing to accept Bathory’s role in the slaughter of an estimated 640 young women if it was motivated by vanity rather than by sadism or a simple bloodlust. In Borowczyk’s telling of the Bathory legend, Bathory bathes in the blood of the slaughtered girls, but this has no effect on her appearance: she begins the segment as young and, at the end of the segment, remains the same age. Bathory’s actions, therefore, seem motivated by an inexplicable bloodlust or fetish. By contrast, Sasdy’s film emphasises Bathory’s vanity: Bathory begins the film as an elderly widow who, after accidentally discovering the youth-giving effects of bathing in blood, falls in lust/love with Imre Toth, which leads her to develop an insatiable desire to remain youthful.  Dobi does his best to attack Bathory’s vanity, telling her, the first time she reverts back to her ‘true’ age, ‘Don’t you realise you get uglier each time you get old? You can’t go on killing forever’. He ridicules her fantasies. When she pleads with him to help her find another virgin girl to slaughter, after she has once again returned to her true age, Dobi tells her, ‘You cheated me. You knew this would happen and you made a fool of me. What do you want? That we should make love, now, as you are? Like two old fools fumbling at each other?’ ‘Don’t be cruel. Help me’, Bathory pleads. ‘Why should I help you? You don’t want me. It’s him, Imre […] you’re thinking about and how you’ll look for him tomorrow. But you still need me, don’t you? As a whore needs her pander’. Dobi does his best to attack Bathory’s vanity, telling her, the first time she reverts back to her ‘true’ age, ‘Don’t you realise you get uglier each time you get old? You can’t go on killing forever’. He ridicules her fantasies. When she pleads with him to help her find another virgin girl to slaughter, after she has once again returned to her true age, Dobi tells her, ‘You cheated me. You knew this would happen and you made a fool of me. What do you want? That we should make love, now, as you are? Like two old fools fumbling at each other?’ ‘Don’t be cruel. Help me’, Bathory pleads. ‘Why should I help you? You don’t want me. It’s him, Imre […] you’re thinking about and how you’ll look for him tomorrow. But you still need me, don’t you? As a whore needs her pander’.

The film was trimmed slightly for its release in the US, in order to achieve a ‘PG’ rating. The American distributor excised the nudity and made cuts to the scenes that depicted Bathory bathing in blood. This is, of course, the full British version of the film, with a running time of 93:03 mins.

Video

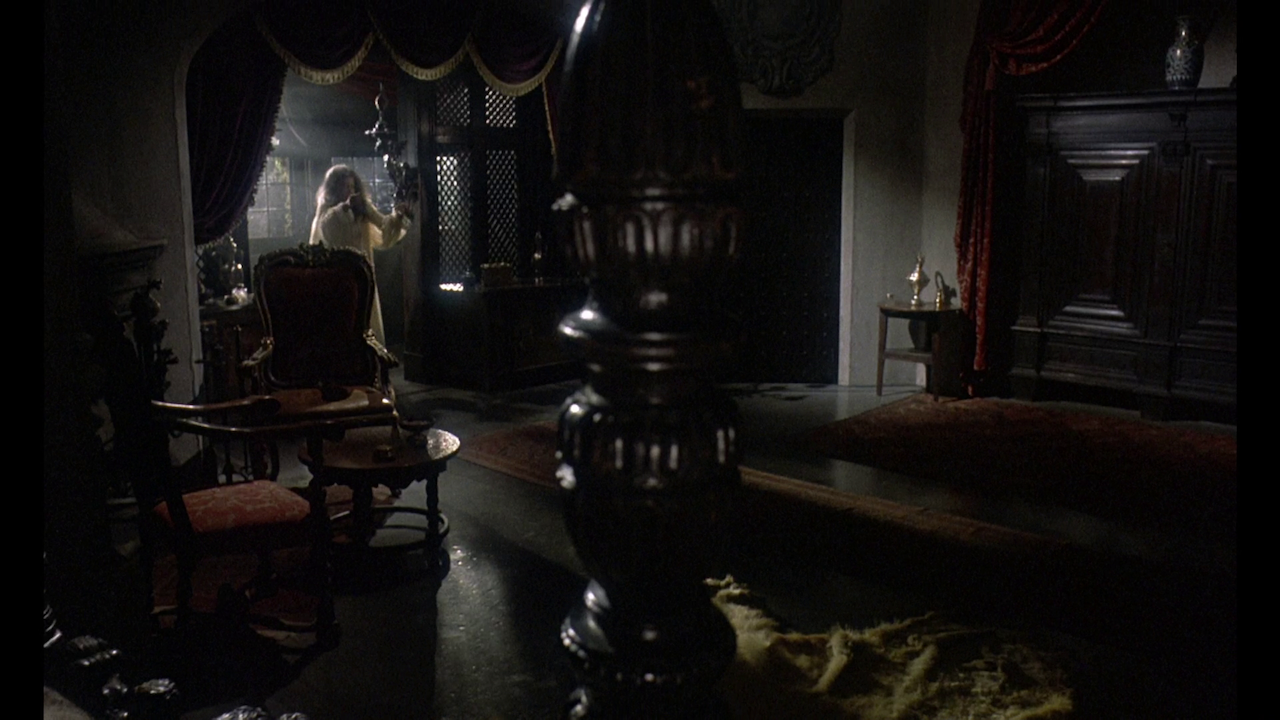

Given the setting in Hungary, which has bright vibrant summers and deep, cold winters (with the mountainous regions often seeing heavy snowfall during winter months), the film’s photography is curiously ‘flat’. (It would have been interesting to see the narrative play out against a cold, frozen landscape covered with snow, for example.) The photography in many sequences has a diffused look to it, which seems to have been achieved through the use of diffusion filters which were possibly intended to mask the age of Pitt, then in her mid-thirties, in the scenes in which Bathory is masquerading as the twenty year old Ilona; this can be seen in the numerous scenes that feature candlelight, flames and the reflection of sunlight off the surface of water. In fact, the use of diffusion filters (and not just in portrait shots, where their use would be masked slightly by the footage surrounding it) gives a generally ugly appearance to some of the sequences set inside the castle, with scenes featuring strong light sources (candles, open flames) having an appearance that resembles the experience of being ‘bleary-eyed’ upon waking in the morning – when the filmmakers appear to have been intending for those filters to add an ethereal atmosphere. As such, the HD presentation on offer here highlights the curious characteristics of the original photography. On this note, it’s worth noting that there’s a shot at approximately 41 minutes into the film, in which two young boys discover a body outside the castle, that has the appearance of 35mm film that has been ‘pushed’ but not processed properly – a very coarse grain structure and contrast that seems a little ‘off’; one may speculate that it was a shot that was underexposed during filming and the footage was ‘pushed’ slightly in postproduction as a means of making it match the exposure within the shots that surround it (the build-up to the boys finding the body). Either way, the shot appears the same on the Synapse Blu-rays and, I am informed, the European Blu-ray discs; it’s a product of the original photography rather than a flaw within this digital presentation. Given the setting in Hungary, which has bright vibrant summers and deep, cold winters (with the mountainous regions often seeing heavy snowfall during winter months), the film’s photography is curiously ‘flat’. (It would have been interesting to see the narrative play out against a cold, frozen landscape covered with snow, for example.) The photography in many sequences has a diffused look to it, which seems to have been achieved through the use of diffusion filters which were possibly intended to mask the age of Pitt, then in her mid-thirties, in the scenes in which Bathory is masquerading as the twenty year old Ilona; this can be seen in the numerous scenes that feature candlelight, flames and the reflection of sunlight off the surface of water. In fact, the use of diffusion filters (and not just in portrait shots, where their use would be masked slightly by the footage surrounding it) gives a generally ugly appearance to some of the sequences set inside the castle, with scenes featuring strong light sources (candles, open flames) having an appearance that resembles the experience of being ‘bleary-eyed’ upon waking in the morning – when the filmmakers appear to have been intending for those filters to add an ethereal atmosphere. As such, the HD presentation on offer here highlights the curious characteristics of the original photography. On this note, it’s worth noting that there’s a shot at approximately 41 minutes into the film, in which two young boys discover a body outside the castle, that has the appearance of 35mm film that has been ‘pushed’ but not processed properly – a very coarse grain structure and contrast that seems a little ‘off’; one may speculate that it was a shot that was underexposed during filming and the footage was ‘pushed’ slightly in postproduction as a means of making it match the exposure within the shots that surround it (the build-up to the boys finding the body). Either way, the shot appears the same on the Synapse Blu-rays and, I am informed, the European Blu-ray discs; it’s a product of the original photography rather than a flaw within this digital presentation.

The 1080p presentation here takes up approximately 16Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, and the presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation seems to be based on the same source as that used for the Synapse Blu-ray. The two discs appear virtually identical, though the encode on the Synapse disc is noticeably stronger. Here, the grain structure looks a little ‘clumpy’ in places, almost as if the encode is struggling to resolve the information within the image. However, the level of detail is good; in some scenes, though, there seem to be some crushed blacks. In all, it’s a pleasing presentation, a significant improvement over the DVDs that are available (some of which featured a noticeably ‘zoomboxed’ transfer) but is let down slightly by the encode. NB. Some larger captures from the Blu-ray are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless LPCM (two-channel) mono track which contains good range, evident in the atmospheric score (the main titles theme features ominous rumbling and breezy woodwind instruments, etc). Frustratingly, as viewers familiar with the film will know, for whatever reasons Ingrid Pitt’s sultry voice was dubbed in post-production by another actress with a less distinctive accent. (Pitt has suggested that relationships during the production of the film were less than harmonious, so this may be the reason for the dubbing of Pitt’s character, or perhaps her accent was seen as a ‘problem’.) There are other curious aspects in relation to the sound design within the film: for example, some of the actors appear to attempt Hungarian accents, whilst others don’t bother at all. The dialogue thus comes across as rather schizophrenic. Nevertheless, the audio track on this disc offers a solid presentation of the film’s original sound track. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc contains a wealth of extras, different from those included on the American Blu-ray. This disc contains: An audio commentary with Ingrid Pitt and critics Kim Newman & Stephen Jones. This is the same lively and informative audio commentary that appeared on Network’s SE DVD. Pitt, as ever, offers some vivid recollections (notably, she refers to Peter Sasdy as ‘disgusting’ and ‘hateful’), and Newman and Jones’ comments on the film are infectiously enthusiastic. An archive interview with Ingrid Pitt (6:33). This is taken from Yorkshire Television’s Tonight magazine programme, and features Pitt talking at the time of the publication of her autobiography Life’s a Scream. It’s a fairly superficial interview (Tonight was a teatime magazine show) but nevertheless offers some interesting reflections by Pitt on her career as a whole. '50 Years of Hammer' news feature (1:57). This, again, is from 1999; it’s a short feature from ITV news which covers the celebrations surrounding the 50th anniversary of Hammer films. The news report declares that ‘the future of Bray Studios’ is ‘assured’, but sadly things have changed over the past few years, and it seems that despite the best efforts of the ‘Save Bray Studios’ campaign Bray Studios is destined to be demolished and replaced with housing. Thriller episode: 'Where the Action Is' (64:19). An episode of the 1970s anthology series Thriller, ‘Where the Action Is’ features Ingrid Pitt. Like the majority of Thriller episodes, it’s tense and deeply enjoyable; but its connection with Countess Dracula is tangential. Conceptions of Murder episode: 'Peter and Maria' (25:04). Again, the relationship of this episode with Countess Dracula is tangential. The episode, from the short-lived anthology series Conceptions of Murder (which I don’t believe has been released on DVD yet), features Nigel Green as German serial killer Peter Kurten, the ‘Vampire of Dusseldorf’. It may have little to do with Countess Dracula, but, with a strong script by Clive Exton, it’s definitely worth watching. Trailer (2:56) Galleries: - Production (9:27) - Behind the Scenes (7:00) - Portrait (6:18) - Promotional (2:27) (The titles of these galleries are self-explanatory.) Retail versions of this release include a booklet with content written by Toby Jones, which also contains an extract from The Ingrid Pitt Book of Murder, Torture and Depravity.

Overall

The film’s narrative is curiously ‘flat’, given the material. Certain aspects of the film have the universal appeal of a fairy tale (the imprisonment of the real Ilona by a Mongolian brute after being trapped in a forest, whilst the Countess masquerades as her own daughter in a plot to seduce the handsome young soldier Imre Toth). However, one can’t help but agree with Ingrid Pitt’s belief that Sasdy should have explored the more extreme possibilities presented by the Bathory legend. Pitt has suggested that the film was torn between the ‘historical aspect […] which Alexander Paal and Peter Sasdy tried very hard to emphasize’ and the ‘idea of making a Hammer horror film’ (Pitt, quoted in Cotter, 2010: 57). Sasdy apparently wanted the film to have a more subtle title, one which emphasised the historical aspects of the film rather than the horror elements (Pitt, in ibid.). The result was that ‘there was a lot of acrimony on the set’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.). However, as Pitt asserts, ‘when you make a film with Hammer and it is called Countess Dracula, it ought to be Countess Dracula!’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.). Pitt felt that the film should be more bloody: for ‘the scene where the barmaid is murdered and there’s no blood[,] I said to him [Sasdy], “Please, hang the girl up by her feet, cut her open, and let the blood flow from her body and let the countess wash the blood all over herself … let her bathe in the girl’s blood!”’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.). The film’s narrative is curiously ‘flat’, given the material. Certain aspects of the film have the universal appeal of a fairy tale (the imprisonment of the real Ilona by a Mongolian brute after being trapped in a forest, whilst the Countess masquerades as her own daughter in a plot to seduce the handsome young soldier Imre Toth). However, one can’t help but agree with Ingrid Pitt’s belief that Sasdy should have explored the more extreme possibilities presented by the Bathory legend. Pitt has suggested that the film was torn between the ‘historical aspect […] which Alexander Paal and Peter Sasdy tried very hard to emphasize’ and the ‘idea of making a Hammer horror film’ (Pitt, quoted in Cotter, 2010: 57). Sasdy apparently wanted the film to have a more subtle title, one which emphasised the historical aspects of the film rather than the horror elements (Pitt, in ibid.). The result was that ‘there was a lot of acrimony on the set’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.). However, as Pitt asserts, ‘when you make a film with Hammer and it is called Countess Dracula, it ought to be Countess Dracula!’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.). Pitt felt that the film should be more bloody: for ‘the scene where the barmaid is murdered and there’s no blood[,] I said to him [Sasdy], “Please, hang the girl up by her feet, cut her open, and let the blood flow from her body and let the countess wash the blood all over herself … let her bathe in the girl’s blood!”’ (Pitt, quoted in ibid.).

Countess Dracula is immensely watchable, thanks to the performance of Pitt (and the ever-dependable Nigel Green), but the script seems pulled in too many directions, unsure of whether it’s a historical drama or a salacious take on the Bathory legend. The use of diffusion filters in the photography adds a slightly ugly aspect to the film’s aesthetic, which is arguably emphasised by its presentation in HD, but regardless of this the presentation of the film on this Blu-ray disc is quite pleasant, and similar in many ways to the Blu-ray released in the States by Synapse, earlier this year. (Certainly, the two releases appear to be based on the same source.) I have reservations about the encode, which could be stronger: the film takes up only 16Gb of a single-layered disc, and as noted above it sometimes seems to struggle to resolve detail from time to time, resulting in grain that sometimes has the appearance of video noise. Nevertheless, it’s still a big improvement over the DVDs that have been available. With some interesting, exclusive contextual material (which has been ported over from Network’s SE DVD release from 2007), Network’s Blu-ray release of Countess Dracula offers a more than satisfying way to view the film. References: Cotter, Robert Michael, 2010: Ingrid Pitt, Queen of Horror: The Complete Career. London: McFarland Forshaw, Barry, 2013: British Gothic Cinema. London: Palgrave Macmillan Hutchings, Peter, 1993: Hammer and Beyond: The British Horror Film. Manchester University Press Kord, Susanne, 2009: Murderesses in German Writing, 1720-1860: Heroines of Horror. Cambridge University Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|