|

|

Incredible Melting Man (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th October 2014). |

|

The Film

The Incredible Melting Man (William Sachs, 1977)  A throwback to 1950s science fiction films, The Incredible Melting Man (William Sachs, 1977) married the concerns of those pictures – principally, their exploration of scientific hubris and its potential consequences – with the extreme imagery of the ‘body horror’ films popular during the 1970s and 1980s (for example, David Cronenberg’s Rabid, 1977), and elements of the narrative structure associated with the then-burgeoning bodycount/stalk-and-slash/slasher films that had already been established in films like Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) but would become increasingly important after the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978. A throwback to 1950s science fiction films, The Incredible Melting Man (William Sachs, 1977) married the concerns of those pictures – principally, their exploration of scientific hubris and its potential consequences – with the extreme imagery of the ‘body horror’ films popular during the 1970s and 1980s (for example, David Cronenberg’s Rabid, 1977), and elements of the narrative structure associated with the then-burgeoning bodycount/stalk-and-slash/slasher films that had already been established in films like Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) but would become increasingly important after the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978.

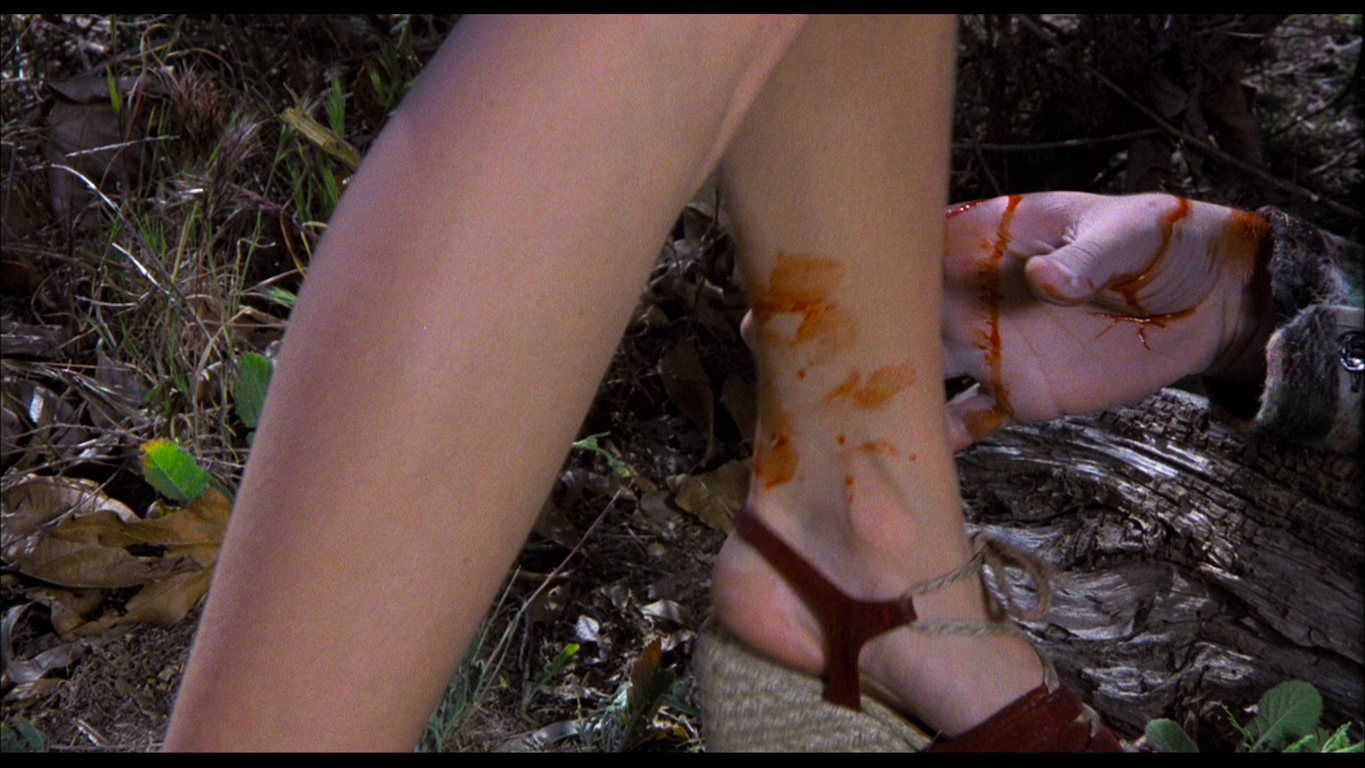

The film begins with a journey to Saturn by a spacecraft, Scorpio 5, in which one of the astronauts, Steve West (Alex Rebar), declares that ‘No-one has ever seen anything like this’ and asserts that ‘You haven’t lived until you’ve seen the sun through the rings of Saturn’. However, the spacecraft is hit by a solar flare, presumably refracted through Saturn’s rings. What happens to the rest of the crew is left ambiguous, but the next time we see Steve, he is in a hospital bed, covered from head to foot with bandages. He awakens and, peeling the bandages from his face and hands, is horrified by what he sees in the mirror. He chases a nurse who enters the room to attend to him and, outside the hospital, partially devours her.  Meanwhile, Dr Ted Nelson (Burr DeBenning), Steve’s friend, is commanded by General Perry (Myron Healey) to track down the missing astronaut, but is commanded to maintain secrecy about the mission: the public believe that the astronauts from the Scorpio 5 mission returned home safely and are simply being quarantined for a short while after returning home from their journey to space. Nelson and Perry set off in search of Steve; but their hunt for the astronaut, whose body seems to be in a state of rapid decay as a result of being exposed to the radiation in space, is halted by several interruptions, including a stop-off at Ted’s house, where Ted’s pregnant wife Judy (Ann Sweeny) is preparing a special dinner for her parents. The planned sweet family get together sadly never takes place, as Judy’s parents are interrupted on their journey to the Nelson house by Steve, who devours them in their car. Meanwhile, Dr Ted Nelson (Burr DeBenning), Steve’s friend, is commanded by General Perry (Myron Healey) to track down the missing astronaut, but is commanded to maintain secrecy about the mission: the public believe that the astronauts from the Scorpio 5 mission returned home safely and are simply being quarantined for a short while after returning home from their journey to space. Nelson and Perry set off in search of Steve; but their hunt for the astronaut, whose body seems to be in a state of rapid decay as a result of being exposed to the radiation in space, is halted by several interruptions, including a stop-off at Ted’s house, where Ted’s pregnant wife Judy (Ann Sweeny) is preparing a special dinner for her parents. The planned sweet family get together sadly never takes place, as Judy’s parents are interrupted on their journey to the Nelson house by Steve, who devours them in their car.

Perry is displeased to discover that Ted has revealed the nature of his mission to Judy. As the bodycount begins to pile up, Ted enlists the help of another friend, Sheriff Neil Blake (Michael Alldredge). Meanwhile, as Ted speaks with Neil, Steve returns to the Nelson house and attacks Perry, killing him. Ted and Neil track Steve to a refinery. The stage is set for a bleak conclusion, made even bleaker by the suggestion at the end of the film that the true circumstances surrounding the Scorpio 5 mission will be covered up, and another mission to Saturn is already underway.  As the above synopsis probably suggests, the film has much in common with Nigel Kneale’s original The Quatermass Experiment (BBC, 1953), memorably adapted for the cinema (as The Quatermass Xperiment) by Val Guest in 1955. In The Quatermass Experiment, a space mission results in the disappearance of two of the three astronauts involved in the mission, and the third astronaut exhibits increasingly strange behaviour upon his return to Earth. When this astronaut escapes from hospital, it is down to Professor Quatermass (Andre Morell in the BBC version; Brian Donlevy in Val Guest’s film) to track him down. Like Quatermass, The Incredible Melting Man is a warning against scientific hubris, focusing on the degradation of advanced man to the level of primitive savage – driven by an inexplicable but primal need to consume flesh – owing to humankind’s attempts to overreach themselves. ‘Remember now’, Ted tells Perry, ‘his [Steve’s] mind is so completely decomposed that by now there’ll be no… there’ll be no rational moves. Well, except for just occasional flashes, but no pattern. He’s gonna need human cells to live on. His instinct will tell him to kill’. The involvement of General Perry in covering up the events implicates the military-industrial complex in Steve’s plight, and to some extent the film demonstrates an oblique criticism of corrupt systems of power that facilitate such disasters and then attempt to cover them up. In some ways, Steve is therefore a variation of Frankenstein’s creation, a monster manufactured by science. The film even hits some of the same beats as Mary Shelley’s novel, with a scene featuring some children encountering Steve in the woods echoing the encounter between Frankenstein’s creation and the little girl. The parallels between Steve and ‘the Adam of [Frankenstein’s] labours’ is hammered home when one of the children, a little girl, runs home to her mother and asserts, ‘I saw Frankenstein [sic] in the woods’. ‘There’s no such thing as Frankenstein’, the girl’s mother tells her, ‘It’s just a story [….] Like Snow White’. (Admittedly, the precise parallels between Shelley’s novel and Snow White are hard to discern.) As the above synopsis probably suggests, the film has much in common with Nigel Kneale’s original The Quatermass Experiment (BBC, 1953), memorably adapted for the cinema (as The Quatermass Xperiment) by Val Guest in 1955. In The Quatermass Experiment, a space mission results in the disappearance of two of the three astronauts involved in the mission, and the third astronaut exhibits increasingly strange behaviour upon his return to Earth. When this astronaut escapes from hospital, it is down to Professor Quatermass (Andre Morell in the BBC version; Brian Donlevy in Val Guest’s film) to track him down. Like Quatermass, The Incredible Melting Man is a warning against scientific hubris, focusing on the degradation of advanced man to the level of primitive savage – driven by an inexplicable but primal need to consume flesh – owing to humankind’s attempts to overreach themselves. ‘Remember now’, Ted tells Perry, ‘his [Steve’s] mind is so completely decomposed that by now there’ll be no… there’ll be no rational moves. Well, except for just occasional flashes, but no pattern. He’s gonna need human cells to live on. His instinct will tell him to kill’. The involvement of General Perry in covering up the events implicates the military-industrial complex in Steve’s plight, and to some extent the film demonstrates an oblique criticism of corrupt systems of power that facilitate such disasters and then attempt to cover them up. In some ways, Steve is therefore a variation of Frankenstein’s creation, a monster manufactured by science. The film even hits some of the same beats as Mary Shelley’s novel, with a scene featuring some children encountering Steve in the woods echoing the encounter between Frankenstein’s creation and the little girl. The parallels between Steve and ‘the Adam of [Frankenstein’s] labours’ is hammered home when one of the children, a little girl, runs home to her mother and asserts, ‘I saw Frankenstein [sic] in the woods’. ‘There’s no such thing as Frankenstein’, the girl’s mother tells her, ‘It’s just a story [….] Like Snow White’. (Admittedly, the precise parallels between Shelley’s novel and Snow White are hard to discern.)

The film has a meandering sense of pace, with odd sidebars to the main narrative. After Steve kills a fisherman, we are presented with a protracted, non-diegetic scene (in the sense that it advances the narrative in no way at all) in which this fisherman’s severed head is shown carried along a river, only to fall from a small waterfall onto the rocks below, causing the skull to crack open. The scene has nothing to say about the hunt for Steve and no importance for the narrative whatsoever, halting the story completely; but it is depicted in loving detail – simply an opportunity to show off Baker’s impressive effects work. Furthermore, there is little to no sense of urgency in Ted and General Perry’s attempts to track down Steve, with the two stopping off at the Nelson family house for a dinner cooked by Judy – leading to the revelation that Judy’s parents have disappeared on their way to their daughter’s home. Likewise, during a conversation with his wife Judy about Steve’s escape from the hospital, Ted continually loses focus on the topic to remind his wife that he asked her to buy some crackers. ‘Oh, God. What are you going to do?’, Judy asks after discovering that Steve has escaped and killed a nurse. ‘Did you get some crackers?’, is Ted’s response: ‘I told you yesterday that we needed some crackers’. ‘So what about Steve?’, Judy asks. ‘So, we don’t have any crackers?’, the easily distracted Steve enquires. ‘Ted’, Judy says in an attempt to bring her husband back round to the important topic, ‘Steve?’ ‘Steve?’, Ted responds blankly, ‘I’ve got to go out and find Steve’. The film has a meandering sense of pace, with odd sidebars to the main narrative. After Steve kills a fisherman, we are presented with a protracted, non-diegetic scene (in the sense that it advances the narrative in no way at all) in which this fisherman’s severed head is shown carried along a river, only to fall from a small waterfall onto the rocks below, causing the skull to crack open. The scene has nothing to say about the hunt for Steve and no importance for the narrative whatsoever, halting the story completely; but it is depicted in loving detail – simply an opportunity to show off Baker’s impressive effects work. Furthermore, there is little to no sense of urgency in Ted and General Perry’s attempts to track down Steve, with the two stopping off at the Nelson family house for a dinner cooked by Judy – leading to the revelation that Judy’s parents have disappeared on their way to their daughter’s home. Likewise, during a conversation with his wife Judy about Steve’s escape from the hospital, Ted continually loses focus on the topic to remind his wife that he asked her to buy some crackers. ‘Oh, God. What are you going to do?’, Judy asks after discovering that Steve has escaped and killed a nurse. ‘Did you get some crackers?’, is Ted’s response: ‘I told you yesterday that we needed some crackers’. ‘So what about Steve?’, Judy asks. ‘So, we don’t have any crackers?’, the easily distracted Steve enquires. ‘Ted’, Judy says in an attempt to bring her husband back round to the important topic, ‘Steve?’ ‘Steve?’, Ted responds blankly, ‘I’ve got to go out and find Steve’.

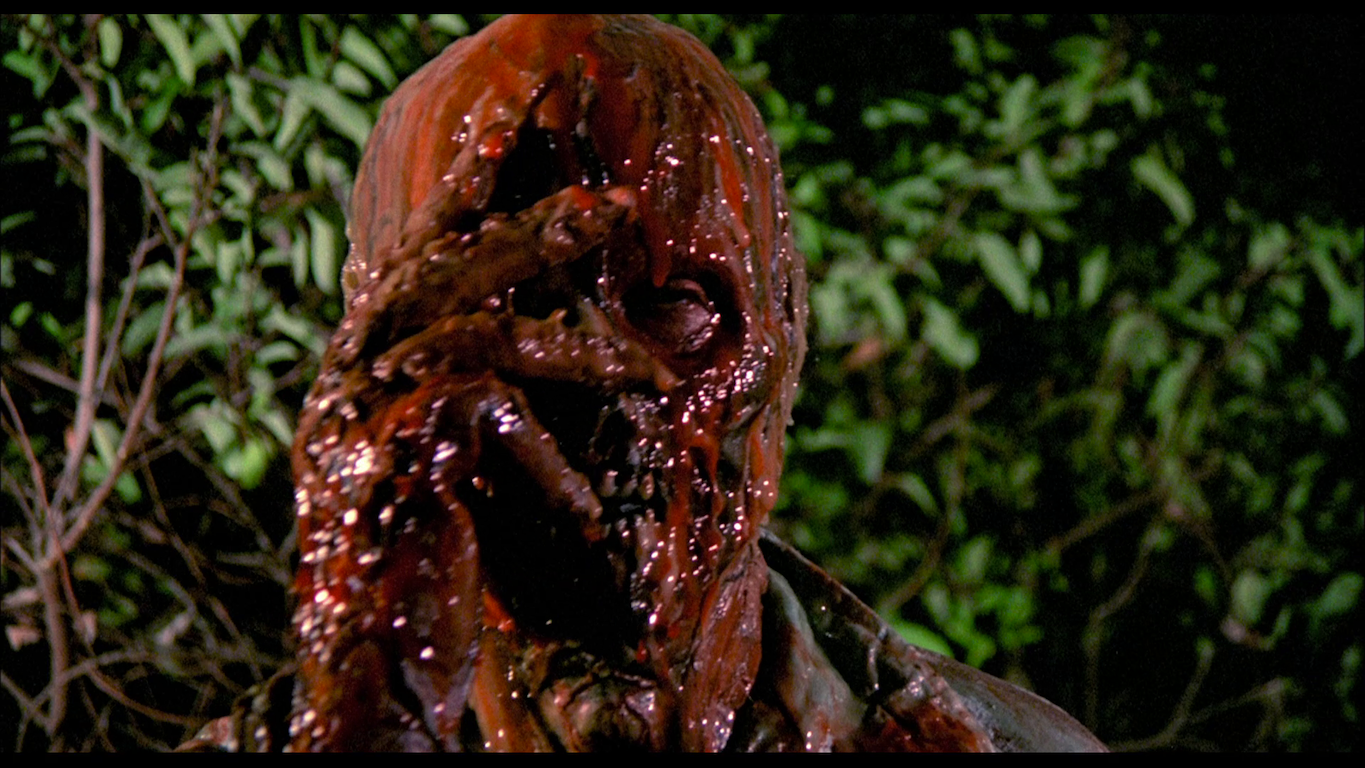

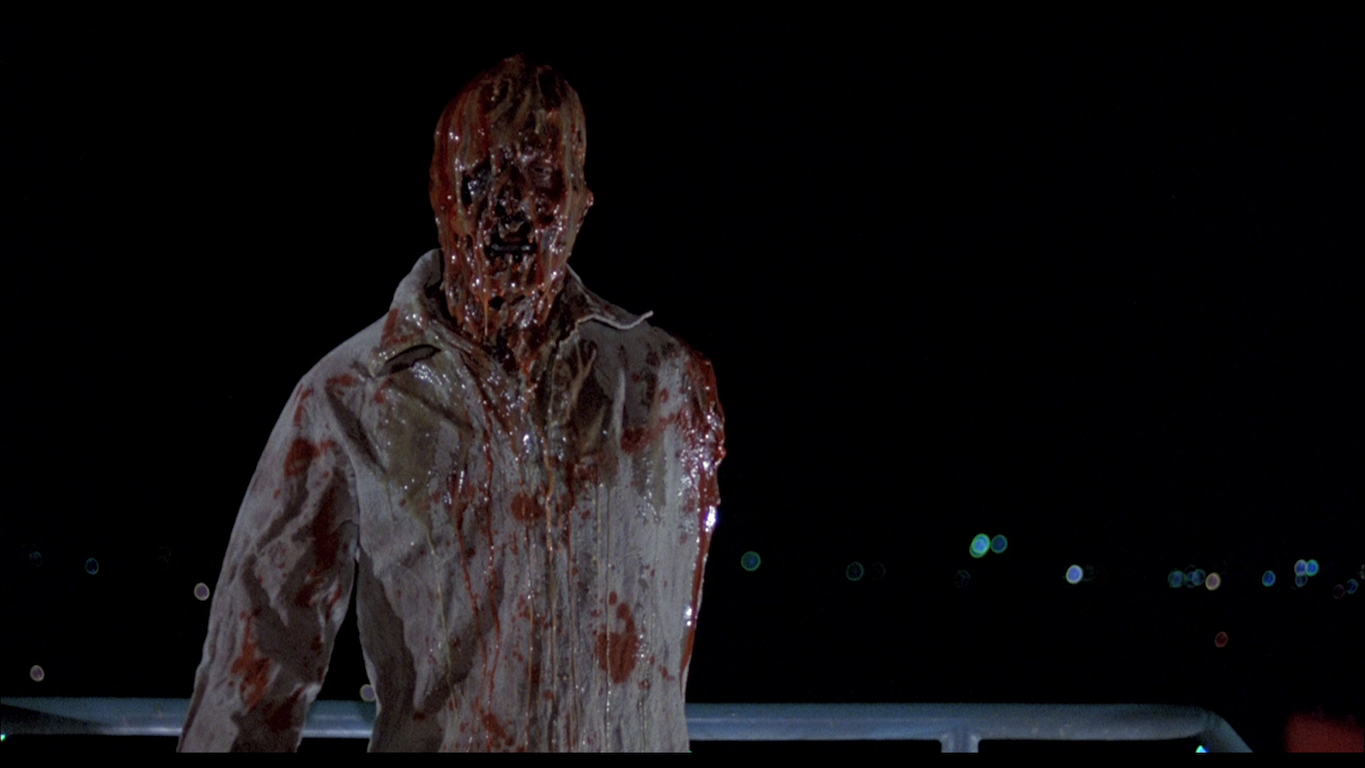

In its odd sense of pacing and the lack of urgency surrounding Ted and Perry’s ‘quest’, the film has some parallels with Lucio Fulci’s City of the Living Dead (1980), in which Christopher George’s journalist and Catriona MacColl’s psychic manage to find time to stop off at a roadside café for a bite to eat during their urgent quest to stop the apocalypse. (One perhaps shouldn’t complain too loudly, as US television’s hit/hip series Supernatural [Warner, 2005-present] has turned this approach to narrative into a fine art, weaving whole seasons around diversions from the Winchester brothers’ attempts to prevent the end of days.) In this context, it’s difficult to know whether or not Judy’s comments about Ted and Perry’s lack of urgency are intended to be ironic: ‘He’s [Steve] running around murdering people’, she observes astutely, ‘And what are you doing about it? I’ve never seen such a feeble excuse for a search in my life. What the hell do you expect him to do, come here and knock on the door?’ As if to reinforce Judy’s point, Sachs intercuts this observation with the murder of Judy’s mother, a sweet old lady whose trip to the Nelson family home was itself interrupted by her husband’s insistence on stopping their journey to go lemon scrumping in the dead of night.  Much of the film’s $250,000 budget was spent on Rick Baker’s effects work. Baker was hired because Sachs had been impressed with Baker’s work on Jeff Lieberman’s Squirm (1976), specifically an effect depicting worms crawling out of a victim’s face. In the interview included on this disc, Baker himself suggests that he didn’t want to work on the film and put in what he thought was an absurd bid which, to his surprise, was accepted. Certainly, the film is part of a group of pictures of the late 1970s/early 1980s which looked back to the invasion narratives of the 1950s, including Harry Thomason’s The Day It Came to Earth (1979) and John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing (1982) – which featured superb effects by Rob Bottin, who incidentally assisted Baker in the production of his effects for The Incredible Melting Man. (Some of Bottin’s effects for The Thing, which has a similar body horror subtext to Sach’s film, may be compared with Baker’s work on this picture.) The Incredible Melting Man also offers parallels with a number of roughly contemporaneous films which focus on the dangers of the human exploration of space, including Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), John Carpenter’s Dark Star (1974) and Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One (1977). Like the latter film, The Incredible Melting Man displays a cynicism towards official discourse, suggesting in its final moments (via a radio broadcast that announces the next mission to Saturn is being planned) that history will repeat itself and the failure of Steve’s mission to space will be subjected to a ‘cover up’. In this sense, like Capricorn One, The Incredible Melting Man exhibits an implicit criticism of the role of the media in perpetuating ‘official’ discourse, intended to deceive and manipulate, in the wake of the Watergate scandal. Much of the film’s $250,000 budget was spent on Rick Baker’s effects work. Baker was hired because Sachs had been impressed with Baker’s work on Jeff Lieberman’s Squirm (1976), specifically an effect depicting worms crawling out of a victim’s face. In the interview included on this disc, Baker himself suggests that he didn’t want to work on the film and put in what he thought was an absurd bid which, to his surprise, was accepted. Certainly, the film is part of a group of pictures of the late 1970s/early 1980s which looked back to the invasion narratives of the 1950s, including Harry Thomason’s The Day It Came to Earth (1979) and John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing (1982) – which featured superb effects by Rob Bottin, who incidentally assisted Baker in the production of his effects for The Incredible Melting Man. (Some of Bottin’s effects for The Thing, which has a similar body horror subtext to Sach’s film, may be compared with Baker’s work on this picture.) The Incredible Melting Man also offers parallels with a number of roughly contemporaneous films which focus on the dangers of the human exploration of space, including Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), John Carpenter’s Dark Star (1974) and Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One (1977). Like the latter film, The Incredible Melting Man displays a cynicism towards official discourse, suggesting in its final moments (via a radio broadcast that announces the next mission to Saturn is being planned) that history will repeat itself and the failure of Steve’s mission to space will be subjected to a ‘cover up’. In this sense, like Capricorn One, The Incredible Melting Man exhibits an implicit criticism of the role of the media in perpetuating ‘official’ discourse, intended to deceive and manipulate, in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

The film is uncut and runs for 86:17 mins.

Video

The presentation of the film takes up a little over 21Gb of space on the disc. The film itself is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, which is by all accounts its intended aspect ratio. The presentation of the film takes up a little over 21Gb of space on the disc. The film itself is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, which is by all accounts its intended aspect ratio.

Contrast in the presentation is generally very good, and the film has a natural, organic appearance, befitting a film shot on colour 35mm stock in the late 1970s. There is some stock space-based footage used to depict the Scorpio 5 mission to Saturn, and this evidences a stronger grain structure – and a different texture overall – than the rest of the material. The level of visible detail is, in most instances, very good. Some of the night-time scenes seem to suffer from crushed blacks, however. There are also some very minor instances of vertical scratches here and there (which are notoriously difficult to remove), but aside from these the presentation is remarkably clean. In addition, there is one brief moment in which the picture judders slightly (in one ten second shot, beginning at 18:55, during the scene in which the young girl playing hide and seek is counting) but this would seem to be an issue with the source material rather than with the encode on this disc. The presentation looks identical to that on the Shout! Blu-ray released in the US last year (2013), but with an arguably stronger encode. (That disc also contained the moment of judder mentioned above, for example.) NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review. Comparison screen grabs from the Shout! disc released in the US will be added within the next day.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This demonstrates good range. It’s a robust track, free of issues. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes: - An audio commentary with William Sachs. This is an interesting commentary with Sachs but is perhaps frustratingly one-sided, especially when compared with the judiciously edited interview with Sachs and Rick Baker that’s also included on this disc. Nevertheless, Sachs is an engaging commentator, and the track is often highly amusing. - The Super 8 digest version of the film (6:59). This is a welcome addition, which sets the package apart from the US Blu-ray. - An interview with William Sachs and Rick Baker (19:38). Interviewed separately, Sachs and Baker offer very different approaches to the film. Sachs declares the film to be ‘a glop movie’ and discusses its origins (as ‘The Ghoul from Outer Space’). He says that the film was intended to be a comic book-style film with a more enigmatically-structured narrative, in which the identity of the monster (as an astronaut who was part of a disastrous mission to space) wasn’t revealed until then denouement. However, Sachs suggests, the producers wanted ‘a serious horror film’ and pushed the picture in that direction: where Sachs wanted the film to be an outrageous rollercoaster, the producers wanted it to be more ‘based and grounded, like you don’t go on the rollercoaster, you stand there and look at the rollercoaster’. Noting that the picture was one of the final films about radiation, Sachs observes that ‘radiation is one of the scarier things out there now, and it’s real’. Sachs also argues that many of the films comic elements were intentional and were designed to offer a satirical approach to the conventions of the genre. Meanwhile, Rick Baker suggests that the film’s humour ‘came out when the film was put together’ and was the product of ‘some not very good performances and some editorial choices’. Baker also notes that the film’s first editor assembled an edit of the film that contained some almost avant-garde techniques that angered the producers, who had the film recut using more conventional editing techniques. Baker suggests that Rebar was something of a diva, who claimed to be a big star in Italy, provoking Baker to state, ‘I’ve never heard of you and now you’re playing the fucking Incredible Melting Man’. - An interview with Greg Cannom (2:53). Cannom, who assisted Baker in producing the effects for the film, reflects on his involvement in the picture and his work with Baker. - Promotional gallery (4:22). This is a gallery of promotional art - Theatrical trailer (1:01).

Overall

By objective standards, The Incredible Melting Man can’t really be labelled a ‘good’ film. However, it is arguably an important film of sorts, which has lingered in the minds of audiences, largely thanks to its vivid promotional material foregrounding Rick Baker’s impressive monster. (I remember reading about the film after seeing it mentioned in various magazines and books, and then getting hold of the paperback novelisation, years before I finally managed to see the picture.) Thanks to this, the film has developed a cult following over the years. Sachs has insisted that the film doesn’t represent his original intentions, owing to the meddling of the producers, and this is the reason for its weaker aspects. He also suggests that the parodic elements within the film were intentional. This may or may not be true, but regardless there’s certainly much to enjoy here, and the film is deliciously off-kilter in places. When Steve kills Perry, Neil and Ted stumble across his corpse. Nearby, they discover something gruesome wrapped in a paper napkin. They initially believe this object to be a part of Steve, but soon realise that it is the turkey leg that Perry was eating when he was killed. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray disc is very impressive, with some good contextual material too. The inclusion of the condensed 8mm version of the film is a nice touch. Whilst it’s no classic, The Incredible Melting Man is an entertaining little film, and the contextual material in this release is arguably in itself worth the price of entry.

|

|||||

|