|

|

Naked City (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (28th October 2014). |

|

The Film

The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948) The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948)

A milestone in the semidocumentary films noir that were produced after the Second World War, the influence of Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) can be seen in Italian film-inchiesta (documentary-style ‘investigation’ films) such as Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962) and Le mani sulla città (Hands over the City, 1963), and the work of the American film director Sidney Lumet – for example, the naturalistic approach employed by Lumet in both Serpico (1973) and Prince of the City (1981). Its influence can also be read in television, from the series that carried its name (ABC, 1958-63) to Dick Wolf’s long-running Law & Order (NBC, 1990-2010) and, arguably, shows like Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-9) and The Wire (HBO, 2002-8) The semidocumentary films noir appeared after the war, and had a roughly similar approach to the contemporaneous Italian Neo-Realism movement. The first semidocumentary film noir is usually cited as being The House on 92nd Street (1945), a film in which the director, Henry Hathaway, employed some of the techniques associated with newsreels to give the film’s narrative a sense of authenticity. The House on 92nd Street was produced as the first of a series of ‘living journalism’ films that were made for Fox by the producer Louis de Rochement, and featured the hallmarks of later semidocumentary films noir: the omniscient narration, heavy use of location shooting, a focus on police procedure, the intermingling of fictional material with documentary footage, and the use of non-professional actors. Hathaway directed a number of other semidocumentary films noir, including 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) and Call Northside 777 (1948). These films often found their inspiration in true stories and provided a strong focus on elements of police procedure, emphasising authenticity and a documentary-like observational approach to their subject matter. Other examples of this trend within American films noir include Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery (1950) and Elia Kazan’s Boomerang! (1947).  After his contract with MGM expired in 1947, Dassin signed up with a new production unit – contracted to Universal – created by crime journalist Mark Hellinger, who had produced Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). Hellinger intended for the films he produced to have a greater sense of authenticity than most Hollywood productions, with a stronger emphasis on psychological and social realism, and to make use of real locations rather than studio sets (see Phillips, 2009: 7). After his contract with MGM expired in 1947, Dassin signed up with a new production unit – contracted to Universal – created by crime journalist Mark Hellinger, who had produced Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). Hellinger intended for the films he produced to have a greater sense of authenticity than most Hollywood productions, with a stronger emphasis on psychological and social realism, and to make use of real locations rather than studio sets (see Phillips, 2009: 7).

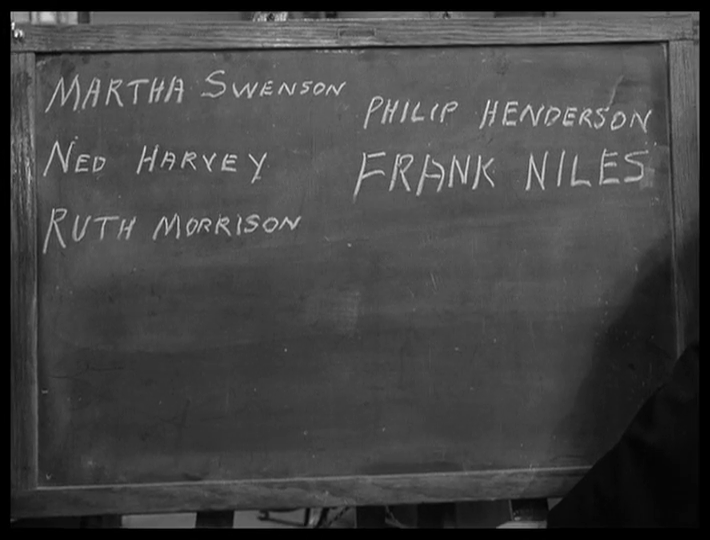

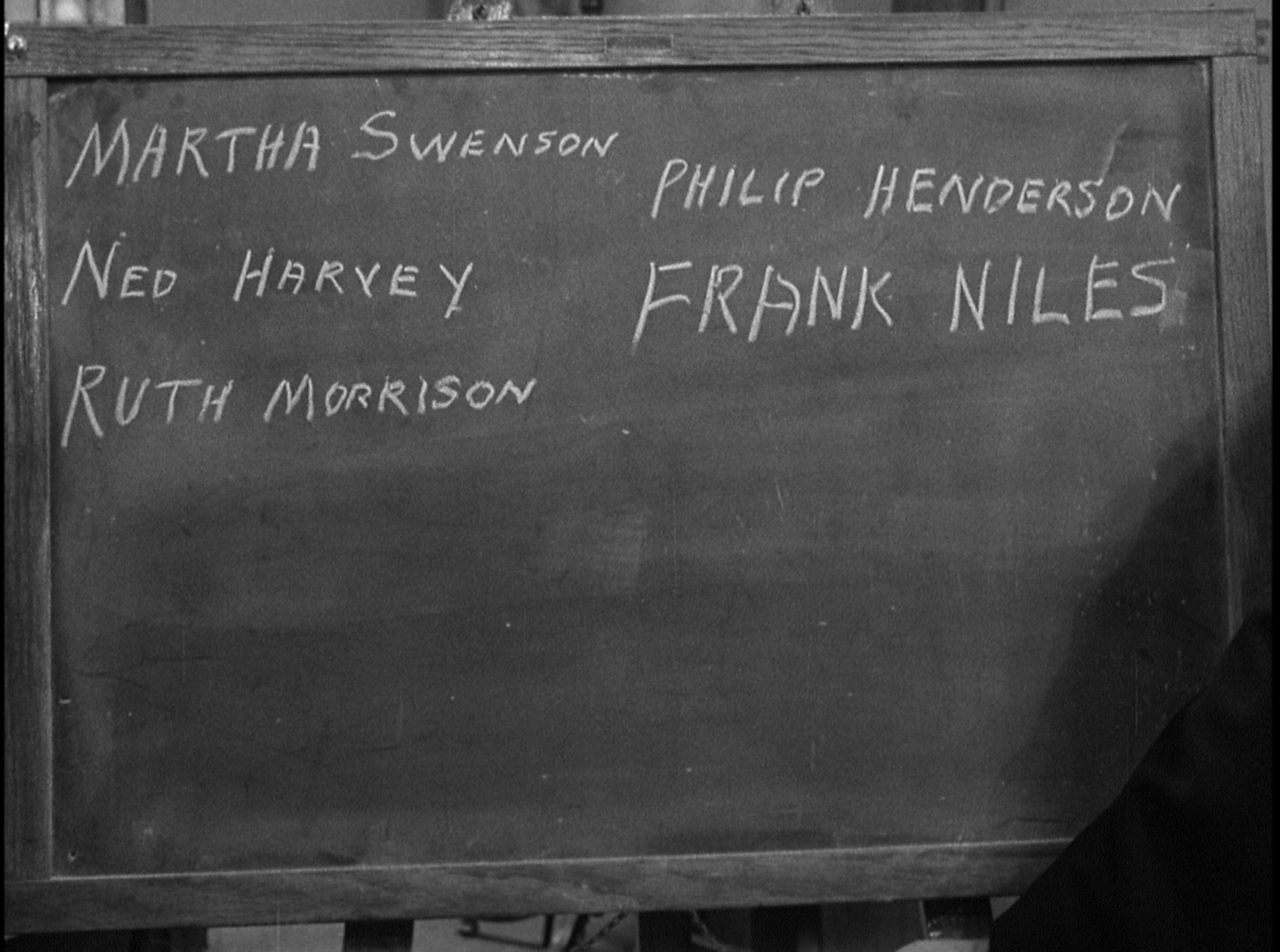

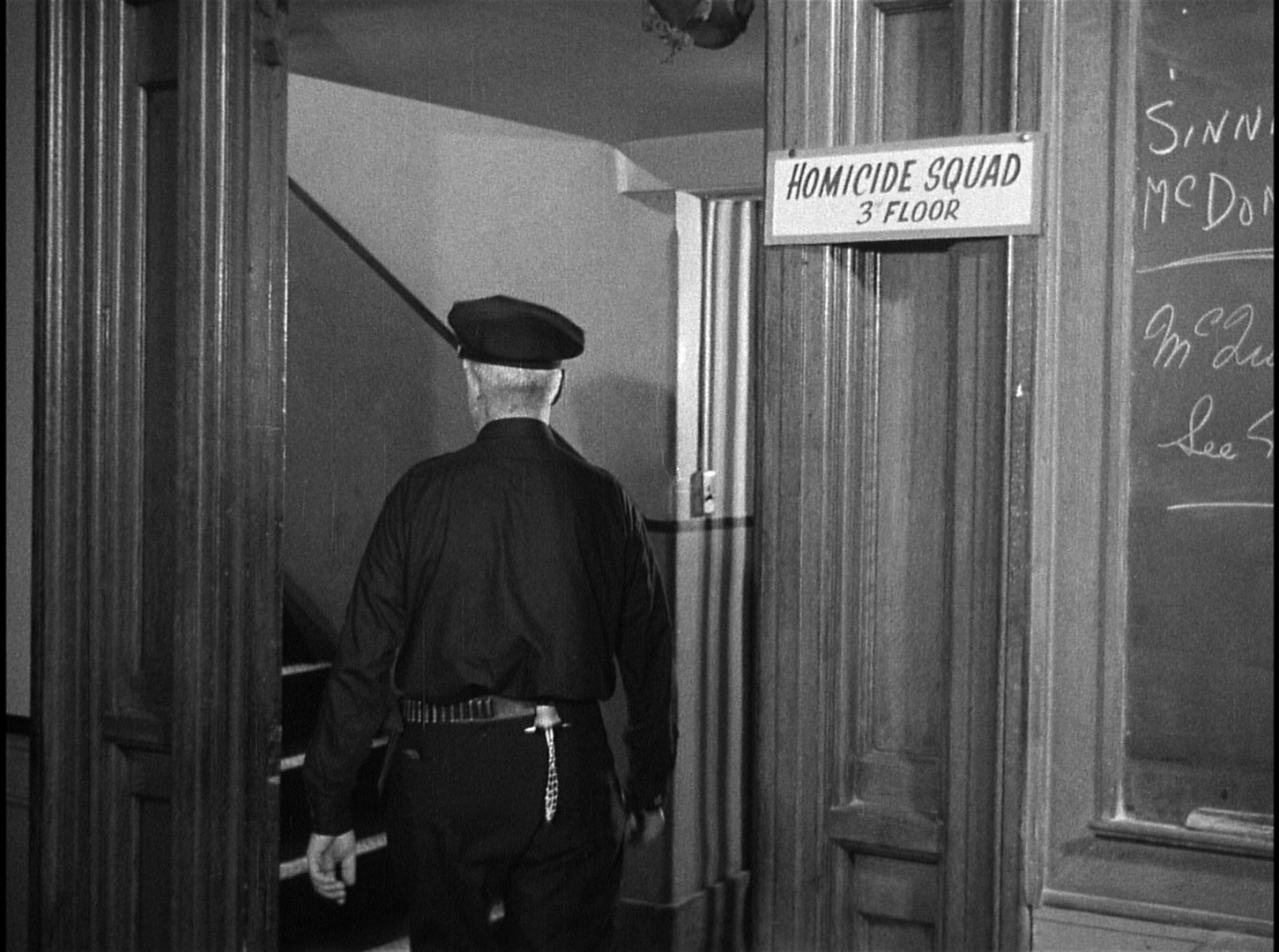

Together, Hellinger and Dassin made the hard-hitting prison drama Brute Force (1947), which ‘reworked familiar wartime themes of collective action against fascist tyranny’, transferring these ‘from the combat unit to a prison’ (Mayer, 2012: 107). With both this film and Dassin’s subsequent picture, The Naked City, Hellinger and Dassin ‘avoided the presence of any prominent stars in order to reflect a more democratic concern for the potential of the ordinary human face’ (ibid.). Of course, however, the lead actor in Brute Force, Burt Lancaster, would later go on to be one of Hollywood’s most enduring stars. The Naked City took its title and its approach to New York from the photographer Arthur Fellig’s (who acquired the nickname ‘Weegee’ during his days as a photojournalist, for his uncanny ability to arrive on crime scenes before the police) 1945 book documenting life in the Big Apple. Both Hellinger and Weegee had a journalistic background and an equally journalistic sensibility. The title of Weegee’s book suggested a city stripped bare (‘naked’) of pretensions and artifice – an honest and truthful account of the city’s underbelly. Weegee’s book adopted the iconography of poverty that characterised photographer Jacob Riis’ influential How the Other Half Lives (1890), which offered an expose of the living conditions of the poor in New York City, and also looked towards Lewis Hine’s reform-oriented documentary photography focusing on labour conditions. The images in Weegee’s The Naked City offered a mixture of an observational documentary approach (shots of tenement slums, people sleeping on fire escapes) and a tabloid eye for sensationalism (murder scenes, photojournalistic shots of transvestite prostitutes being arrested for soliciting). Ralph Willett notes that Weegee’s ‘intrusive, transgressive camera designed a nocturnal, dramatic world of criminals by means of a work routine that shadowed the forces of law’ (1996: 91). Weegee’s technique was matched in Dassin’s film ‘by the activity of [cinematographer William Daniels’] documentary camera’: parts of the film were shot with cameras that were ‘hidden in phone boxes and fake ambulances’, gathering footage of the city’s inhabitants whilst they were unaware that they were being filmed – ‘a further example of the vulnerability of the urban crowd to spying and surveillance’ (ibid.).  Dassin’s The Naked City was shot for $1.2 million under the shooting title ‘Homicide’, and the intention was that the film’s narrative would, in a semidocumentary fashion, follow an investigation into a murder from the point-of-view of the police detectives. The script was written by Malvin Wald, who proposed to Hellinger the idea that a crime film could be made using similar techniques to those Wald had practised during his time making documentaries for the Army Air Corps during the Second World War. Hellinger sent Wald on a month-long research mission in New York City, where Wald observed the Manhattan Police Department during their investigations, and promised to ‘write an honest film about police detectives’ (quoted in Deutelbaum, 2009: 215). These observations helped to shape the film’s narrative, which is based partly on an amalgamation of several real cases – most directly, the unsolved murder of a model, Dot King. In the film, this is represented in the hunt for the killer of a young model, Jean Dexter, which leads the investigating detectives, Lieutenant Daniel Muldoon (Barry Fitzgerald) and Detective Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor), to a ring of jewel thieves with whom Dexter was involved, including self-confessed ‘heel’ Frank Niles (Howard Duff) and wrestler Willie Garzah (Ted de Corsia). The film’s main narrative was supported by second unit work which was intended to highlight the on-location nature of the shoot. During the filming, the production was plagued with problems associated with shooting on location, including bad weather and crowds that interrupted the production. Dassin’s The Naked City was shot for $1.2 million under the shooting title ‘Homicide’, and the intention was that the film’s narrative would, in a semidocumentary fashion, follow an investigation into a murder from the point-of-view of the police detectives. The script was written by Malvin Wald, who proposed to Hellinger the idea that a crime film could be made using similar techniques to those Wald had practised during his time making documentaries for the Army Air Corps during the Second World War. Hellinger sent Wald on a month-long research mission in New York City, where Wald observed the Manhattan Police Department during their investigations, and promised to ‘write an honest film about police detectives’ (quoted in Deutelbaum, 2009: 215). These observations helped to shape the film’s narrative, which is based partly on an amalgamation of several real cases – most directly, the unsolved murder of a model, Dot King. In the film, this is represented in the hunt for the killer of a young model, Jean Dexter, which leads the investigating detectives, Lieutenant Daniel Muldoon (Barry Fitzgerald) and Detective Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor), to a ring of jewel thieves with whom Dexter was involved, including self-confessed ‘heel’ Frank Niles (Howard Duff) and wrestler Willie Garzah (Ted de Corsia). The film’s main narrative was supported by second unit work which was intended to highlight the on-location nature of the shoot. During the filming, the production was plagued with problems associated with shooting on location, including bad weather and crowds that interrupted the production.

Hellinger suffered a heart attack whilst the film was being shot. The film was edited and Hellinger’s voice-over recorded, but Hellinger died on 22 December, 1947, before the film was released (in March, 1948). Dassin reputedly left the film’s premiere in tears, distraught that the studio had apparently excised from the final cut of the film a number of sequences that underscored the gap between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ (Prime, 2007: 142). The film had presumably undergone closer scrutiny owing to the association of one of the writers, Albert Maltz, with the Communist party: the first hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee had begun whilst The Naked City was in production. Without Hellinger around to ‘protect’ the film, Universal’s executives were free to remove ‘any scene that “smelled of politics”’ (Dassin, quoted in ibid.). ‘Gone were his [Dassin’s] shots of bums on the Bowery’, Rebecca Prime notes, ‘his satirical jabs at Upper East Side socialites; what remained was a portrait of a city that James Agee described as “bursting with energy, grandeur, sunlight, and human variety” but stripped of the stark contrast between wealth and poverty that the director considered its most defining aspect’ (ibid.). The experience led Dassin to swear that ‘he would never make another film’ (ibid.). Dassin, of course, relented, completing one more film in the US, Thieves Highway (1949), before being blacklisted during the production of the film adaptation of Gerald Kersh’s novel Night and the City (1950), which resulted in Dassin being unable to step onto Fox’s lot to edit the film. Most of Dassin’s subsequent films were European productions, beginning with the highly-regarded French crime film Rififi (1954), an adaptation of Auguste Le Breton’s novel Du rififi chez les hommes.  Against Hollywood convention (at the time of the film’s production and since), the crime in The Naked City is solved not through moments of abstract genius or through action but through the dogged persistence of the detectives investigating the case and the technicians who are in charge of the lab work. The narrative does, however, resolve itself in a moment of action, as the killer is traced to the Williamsburg Bridge and, during his attempt to scale it, is shot and killed by the police. In terms of the reception of The Naked City, the film’s unsentimental depiction of policework, its single-minded focus on the work of the police and its suggestion that crimes are solved by perseverance and dogged legwork rather than by moments of genius or action – all of which were relatively ‘new’ but would become key components of many later television productions, including The Naked City, Dragnet (NBC, 1951-9) and Law & Order – proved to be controversial amongst critics and audiences. However, in 1948 it received Academy Awards for both its cinematography and editing. Against Hollywood convention (at the time of the film’s production and since), the crime in The Naked City is solved not through moments of abstract genius or through action but through the dogged persistence of the detectives investigating the case and the technicians who are in charge of the lab work. The narrative does, however, resolve itself in a moment of action, as the killer is traced to the Williamsburg Bridge and, during his attempt to scale it, is shot and killed by the police. In terms of the reception of The Naked City, the film’s unsentimental depiction of policework, its single-minded focus on the work of the police and its suggestion that crimes are solved by perseverance and dogged legwork rather than by moments of genius or action – all of which were relatively ‘new’ but would become key components of many later television productions, including The Naked City, Dragnet (NBC, 1951-9) and Law & Order – proved to be controversial amongst critics and audiences. However, in 1948 it received Academy Awards for both its cinematography and editing.

The film’s opening narration, by Hellinger himself, is accompanied by aerial shots of New York. It’s a rare example of omniscient narration within cinema. ‘My name is Mark Hellinger’, Hellinger intones, ‘I was in charge of the production. And I may as well tell you frankly that it’s a bit different from most films you’ve ever seen’. Hellinger’s opening voiceover highlights the location shooting: ‘It was not photographed in a studio. Quite the contrary. [The actors] played out their roles on the streets, in the apartment houses, in the skyscrapers of New York itself. And along with them, a great many thousand New Yorkers played out their roles also’. Ultimately, Hellinger says, ‘This is the city as it is’. His voiceover also anthropomorphicises the city, comparing it to a living organism: ‘There is a pulse to a city… and it never stops beating’, Hellinger tells us. In its tabloid rhetoric, Hellinger’s opening narration has much in common with Weegee’s introduction to his book The Naked City: ‘For the pictures in this book I was on the scene’, Weegee states, ‘sometimes drawn there by some power I can’t explain, and I caught the New Yorkers with their masks off [….] The people in these photographs are real [….] To me a photograph is a page from life, and that being the case, it must be real’ (Weegee, 1945: 11-2).  This opening narration is presented over a montage of shots of city life, a number of which refer back to the photography in Weegee’s book The Naked City: most obviously, the shots of people sleeping on the fire escapes outside their apartments. In an interesting display of technique, the film then cuts to several workers in different night-time occupations, offering them the chance to narrate – to allow the voices of these proletarian figures to be heard. We see a cleaner mopping the floors of Grand Central Station, a linotype operator setting the print for the morning edition of a newspaper, and a radio disc jockey: ‘It’s wonderful to work on a newspaper: you meet such interesting people’, the linotype operator intones ironically on the soundtrack whilst we are shown him working in isolation at night-time; meanwhile, the disc jockey wonders, ‘Does anyone listen to this programme except my wife?’. This opening narration is presented over a montage of shots of city life, a number of which refer back to the photography in Weegee’s book The Naked City: most obviously, the shots of people sleeping on the fire escapes outside their apartments. In an interesting display of technique, the film then cuts to several workers in different night-time occupations, offering them the chance to narrate – to allow the voices of these proletarian figures to be heard. We see a cleaner mopping the floors of Grand Central Station, a linotype operator setting the print for the morning edition of a newspaper, and a radio disc jockey: ‘It’s wonderful to work on a newspaper: you meet such interesting people’, the linotype operator intones ironically on the soundtrack whilst we are shown him working in isolation at night-time; meanwhile, the disc jockey wonders, ‘Does anyone listen to this programme except my wife?’.

Jean Dexter’s murder, at the hands of two men who drug her and then drown her in her bathtub, is shown briefly, and Hellinger’s narration reminds us that ‘even this too can be called “routine”, in a city of eight million people’. When the police investigation begins, the drudgery of this work is outlined for us in Lieutenant Muldoon’s response to the crime: ‘Haven’t had a hard day’s work since yesterday’, he jokes. The investigation of the crime scene itself is shown in some detail: a montage depicts the process of photographing the body, lifting fingerprints from the objects in the room, and sketching the layout of Dexter’s apartment. This sense of routine and the solving of a crime through dogged perseverance, and the context of the film’s setting in relation to the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, is reinforced by Hellinger’s narration which, over shots of young detective and family man Jimmy Halloran walking through the city, tells us, ‘When it comes to legwork, Detective Jimmy Halloran is an expert. In the war, he walked halfway across Europe with a rifle in his hand. Up until three months ago, he was pounding the beat in the Bronx. And now he’s playing button, button, in a city of eight million people’. Halloran’s experience during the war is contrasted with Frank Niles, the sleazy boyfriend of Dexter’s colleague Ruth Morrison, who also had an affair with Dexter herself. Niles, we are later told, was involved with the gang of jewel thieves who murdered Dexter (in order to get a bigger ‘cut’ of each score), and when he is interviewed by Muldoon he claims to be a veteran of the war. However, he is soon rumbled by Muldoon, leading to Niles’ admission, ‘Alright, I’m a heel’. The lines are drawn between the heroic war veteran Halloran and the deceitful Niles, who escaped wartime service owing to his medical record.  Halloran also has a wife and young son, and in a later sequence we are shown the cost, to his home life, of his commitment to policework: Halloran telephones Muldoon during the late evening, and in a single shot we are shown Halloran, in the foreground, on the telephone whilst Halloran’s attractive wife (Anne Sargent), in the background, leans over the banister, patiently waiting for her husband to turn his attention towards her. In another sequence, which jars strongly with modern ideas about child-rearing (especially in the way that the scene is played mostly for laughs), Halloran returns home to find his wife in a bathing costume. Mrs Halloran flirts with her husband before telling him that he must give their young son ‘a good whipping’ for walking out of the house and taking himself to the local playground. Halloran suggests instead that he give the boy ‘a real talking to’, but his wife tells him, ‘No you won’t. You’ll give him a real whipping, with a strap’. Halloran insists that he can’t do it: ‘If you think it’s so easy, you whip him’. ‘Me? That’s not a woman’s job’, his wife complains. ‘Why does it have to be a man’s job?’, Halloran asks. ‘It’s always a man’s job’, his wife responds. Halloran also has a wife and young son, and in a later sequence we are shown the cost, to his home life, of his commitment to policework: Halloran telephones Muldoon during the late evening, and in a single shot we are shown Halloran, in the foreground, on the telephone whilst Halloran’s attractive wife (Anne Sargent), in the background, leans over the banister, patiently waiting for her husband to turn his attention towards her. In another sequence, which jars strongly with modern ideas about child-rearing (especially in the way that the scene is played mostly for laughs), Halloran returns home to find his wife in a bathing costume. Mrs Halloran flirts with her husband before telling him that he must give their young son ‘a good whipping’ for walking out of the house and taking himself to the local playground. Halloran suggests instead that he give the boy ‘a real talking to’, but his wife tells him, ‘No you won’t. You’ll give him a real whipping, with a strap’. Halloran insists that he can’t do it: ‘If you think it’s so easy, you whip him’. ‘Me? That’s not a woman’s job’, his wife complains. ‘Why does it have to be a man’s job?’, Halloran asks. ‘It’s always a man’s job’, his wife responds.

Dexter’s parents blame their own approach to raising their child for her death. When they are invited to view the body, to confirm her identity, Dexter’s moth asserts, ‘I hate her [Jean] for what she’s done to us’; but as she sees the corpse of her daughter, she weeps – ‘My baby’, she cries. Dexter left home, she tells Muldoon, and changed her name. ‘Wanting too much. That’s why she went wrong’, Dexter’s mother says: ‘Bright lights and theatres and furs and nightclubs. That’s why she’s dead now. Dear God, why wasn’t she born ugly?’ Throughout all this, the sense that the determination of Muldoon and Halloran will solve the crime is rarely in doubt. However, when Muldoon and Halloran investigate separate leads, with Halloran wandering through the streets on his own in search of Willie Garzah, there’s a strong sense of danger: as he gets closer to the enigmatic Garzah, Halloran – who has been humanised through glimpses of his home life in a way which Muldoon has not – seems as much under threat in the urban jungle (the ‘naked city’), as he was during his wartime service. All the while, the sense of routine and perseverance as the key to solving crime is reinforced. ‘That’s the way you run a case, lad’, Muldoon tells Halloran at one point: ‘step by step’. Later, over a montage of shots of Halloran asking people if they can identify Garzah, Hellinger’s narration reinforces the necessary tedium of this task: ‘You go home. You go to bed. You get up. You start over. “Mister, you ever see a man looks like this?” “Mister, you ever see a man looks like this?”’. The film is uncut and runs for 95:56 mins.

Video

The presentation of The Naked City on Arrow’s Blu-ray seems to be based on the same sources as the Criterion DVD release from 2007. However, there’s a significant step up in terms of detail and texture, as the grabs below will suggest. The 1080p presentation of the film takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The presentation of The Naked City on Arrow’s Blu-ray seems to be based on the same sources as the Criterion DVD release from 2007. However, there’s a significant step up in terms of detail and texture, as the grabs below will suggest. The 1080p presentation of the film takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1.

The image is crisp and detailed, with a strong sense of the texture of film. The source material exhibits some damage (vertical lines and scratches here and there), but nothing too distracting and nothing more than should be expected for a film of this vintage. Contrast levels are excellent: the monochrome photography displays very good tonal range, especially in the mid-tones. There are a couple of sequences where the highlights look just a tad too ‘hot’ (some facial detail is lost in the highlights in one or two scenes), but this is no doubt a product of the materials on which this presentation is based. This is a very pleasing presentation of the film, an improvement on the already impressive Criterion DVD. Visual comparison with the Criterion DVD release from 2007. Grabs from the Criterion disc are on top; grabs from Arrow’s Blu-ray are below.

Some more large grabs from the Arrow Blu-ray release can be found at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track, which is clear throughout – though there are a couple of sequences where some dialogue gets buried in the sound mix. This isn’t a failing of this presentation of the film, however: it’s clearly a product of the original sound design. Thankfully, optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

Extras include the same commentary with writer Malvin Wald that was included on the Criterion DVD, and similar footage of Jules Dassin at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (52:01), from 2004. A new documentary featuring Amy Taubin, ‘New York and The Naked City” (39:41), focuses on the film’s relationship with New York City. The disc also includes the famous vintage 16mm short documentary piece by John Berry, from 1950, focusing on the blacklist, entitled ‘The Hollywood Ten’ (14:44). In this documentary, each member of the infamous ‘Hollywood Ten’ makes a short speech denouncing McCarthyism. Berry himself was blacklisted after the production of this documentary. Also present are a stills gallery (1:07) and trailers for The Naked City, Brute Force and Rififi – the latter two of which are also available on Blu-ray from Arrow.

Overall

The influence of Italian Neo-Realism, and specifically Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta (Rome: Open City, 1945), on The Naked City was acknowledged by Dassin: ‘When I saw Rome: Open City’, Dassin once asserted in an interview, ‘I said, “that’s the way we have to go”. To use the documentary form to bring a city to life, to bring a thought to life, using what existed or what could exist’ (quoted in Prime, op cit.: 147-8). The Naked City is a fascinating film whose influence can be seen in many aspects of popular culture. The influence of Italian Neo-Realism, and specifically Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta (Rome: Open City, 1945), on The Naked City was acknowledged by Dassin: ‘When I saw Rome: Open City’, Dassin once asserted in an interview, ‘I said, “that’s the way we have to go”. To use the documentary form to bring a city to life, to bring a thought to life, using what existed or what could exist’ (quoted in Prime, op cit.: 147-8). The Naked City is a fascinating film whose influence can be seen in many aspects of popular culture.

This important film gets the special treatment from Arrow that it deserves. The presentation of the film itself is impressive enough, surpassing the already impressive Criterion DVD release, but the disc also includes some excellent contextual material. Along with Arrow’s recent release of Brute Force and their slightly older release of Rififi, this disc is a must-own for fans of film noir. It would be wonderful if Arrow could give the same treatment to Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway or Night and the City. References: Deutelbaum, Marshall, 2009: ‘Finding the Right Man in The Wrong Man’. In Deutelbaum, Marshall & Poague, Leland (eds), 2009: A Hitchcock Reader. Iowa State University Press (Second Edition): 212-22 Hirsch, Foster, 2008: The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir. Da Capo Press Mayer, Geoff, 2012: Historical Dictionary of Crime Films. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Phillips, Alistair, 2009: French Film Guide: Rififi. London: I B Tauris Prime, Rebecca, 2007: ‘Cloaked in Compromise: Jules Dassin’s The Naked City’. In: Stanfield, Peter et al (eds), 2007: ‘Un-American’ Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. Rutgers University Press Schatz, Thomas, 1999: Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. University of California Press Smith, Imogen Sara, 2011: In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City. London: McFarland Willett, Ralph, 1996: The Naked City: Urban Crime Fiction in the USA. Manchester University Press

|

|||||

|