|

|

Withnail and I (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th November 2014). |

|

The Film

Withnail & I (Bruce Robinson, 1987) and How to Get Ahead in Advertising (Bruce Robinson, 1989) Withnail & I (Bruce Robinson, 1987) and How to Get Ahead in Advertising (Bruce Robinson, 1989)

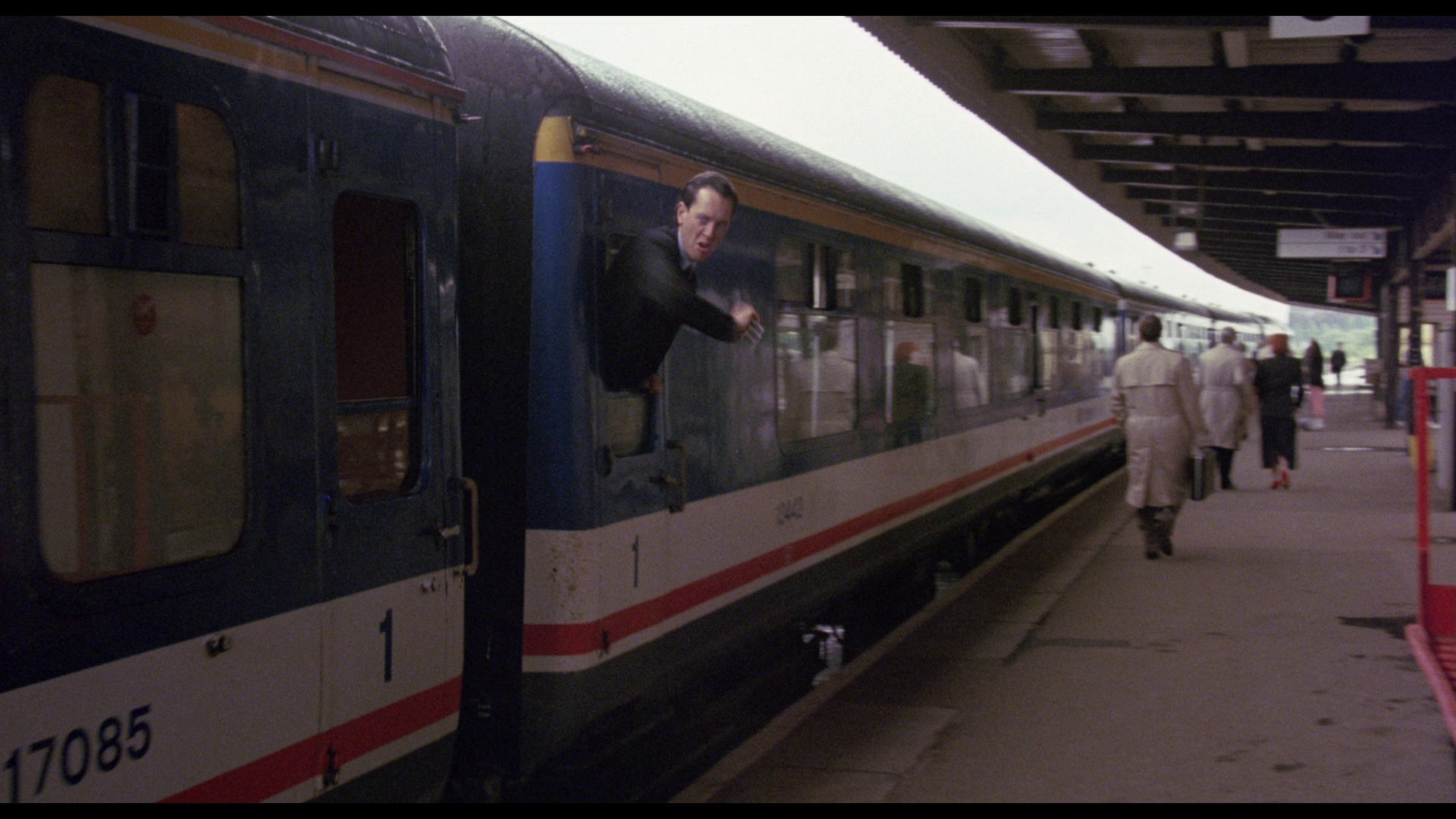

A perennial favourite, Withnail & I (Bruce Robinson, 1987) has gathered a lasting ‘cult’ following. The film itself is, as most its fans know, largely autobiographical, based on Robinson’s youth during the late-1960s and, especially, his friendship with Vivian MacKerrell, with whom during that time Robinson shared a house in Camden. The film has some basis in the anecdotes surrounding Vivian MacKerrell’s alcoholism: like Withnail, for example, MacKerrell did apparently drink lighter fluid during one episode of rampant alcohol abuse, which according to Robinson led to MacKerrell losing his sight for several days. (Roger Ebert once noted that Withnail & I ‘conveys the experience of being drunk so well that the only way I could improve upon it would be to stand behind you and hammer your head with two-pound bags of frozen peas’ - 2010: 391.) MacKerrell – who, legend has it, once returned from a trip to Scotland with bottles of a 200 proof home-made spirit, the imbibation of which led to MacKerrell and Robinson demolishing the walls of their shared house with a hammer and an artificial leg – is represented in the film through the character of Withnail, played with relish in a career-defining performance by Richard E Grant. (Indeed, Grant will arguably forever be associated with his role in Withnail & I.) The ‘and I’ of the title is played by Paul McGann, a blank cipher of a character whose name (‘Marwood’) is never spoken in the dialogue and only briefly glimpsed on a telegram that is shown on-screen. Marwood is a clear stand-in for Robinson himself; Withnail’s Uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths), a tragicomic character who throughout the film insists on making sexual advances towards Marwood, has been claimed to be based on the Italian filmmaker Franco Zeffirelli, who directed Robinson in Romeo and Juliet (1968).  The film details Marwood and Withnail’s life as ‘resting’ actors and their decision to flee London for a while, spending time in the country home of Withnail’s Uncle Monty. The narrative is episodic and as chaotic as the lives of the characters depicted within it, but at the heart of the film is an exploration of the ways in which Marwood comes to realise that his friendship with Withnail is destructive, leading to his decision at the end of the film to leave London and part ways with Withnail. (Robinson apparently originally planned for the film to end with Withnail’s suicide, but ultimately decided against this.) The film details Marwood and Withnail’s life as ‘resting’ actors and their decision to flee London for a while, spending time in the country home of Withnail’s Uncle Monty. The narrative is episodic and as chaotic as the lives of the characters depicted within it, but at the heart of the film is an exploration of the ways in which Marwood comes to realise that his friendship with Withnail is destructive, leading to his decision at the end of the film to leave London and part ways with Withnail. (Robinson apparently originally planned for the film to end with Withnail’s suicide, but ultimately decided against this.)

In its juxtaposition of Monty’s rural retreat with London, Withnail & I has some superficial similarities with Barney Plats-Mills Private Road (1970), in which Withnail & I’s director Bruce Robinson played an author who, with his lover Ann (Susan Penhaligon), retreats to a cottage in Scotland before returning to London where his relationship with Ann begins to sour. Both Withnail & I and Private Road are to some extent films about a character’s rite de passage, and both of them are probably best described as middle-class appropriations of the ‘kitchen sink’ form. Withnail & I was originally written by Robinson in 1969, in the form of a novel; in 1980, Robinson then developed this into a screenplay. The film was produced by HandMade films, the company George Harrison and Denis O’Brien created to finance Monty Python’s Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979) after EMI withdrew from its production, fearing that its controversial subject matter would draw negative attention. HandMade also produced Robinson’s second feature, How to Get Ahead in Advertising, in 1989. The company ceased producing films in 1990, after a number of its pictures flopped in the American market.  Set in 1969, the film represents a watershed, both culturally and in terms of Marwood’s character’s stage of life. The film opens with Marwood, coming down from a high, in a state of panic, squabbling with Withnail over the washing-up. Withnail suggests they venture outside (‘I think we’ve been in here too long. I feel unusual. I think we should go outside’) where, in a park, Withnail foregrounds the anxiety – rooted on the sense of time ‘running out’ – that both he and Marwood seem to face: ‘This is ridiculous’, Withnail says, ‘Look at me. I’m thirty in a month and I’ve got a sole flapping off my shoe [….] Why can’t I have an audition? It’s ridiculous. I’ve been to drama school. I’m good-looking. I tell you, I’ve a fuck sight more talent than half the rubbish that gets on television. Why can’t I get on television? [….] The only programme I’m likely to get on is the fucking news’. Marwood proposes that the pair visit the countryside to rejuvenate, to which Withnail responds: ‘Rejuvenate? I’m in a park and I’m practically dead? What good’s the countryside’. Set in 1969, the film represents a watershed, both culturally and in terms of Marwood’s character’s stage of life. The film opens with Marwood, coming down from a high, in a state of panic, squabbling with Withnail over the washing-up. Withnail suggests they venture outside (‘I think we’ve been in here too long. I feel unusual. I think we should go outside’) where, in a park, Withnail foregrounds the anxiety – rooted on the sense of time ‘running out’ – that both he and Marwood seem to face: ‘This is ridiculous’, Withnail says, ‘Look at me. I’m thirty in a month and I’ve got a sole flapping off my shoe [….] Why can’t I have an audition? It’s ridiculous. I’ve been to drama school. I’m good-looking. I tell you, I’ve a fuck sight more talent than half the rubbish that gets on television. Why can’t I get on television? [….] The only programme I’m likely to get on is the fucking news’. Marwood proposes that the pair visit the countryside to rejuvenate, to which Withnail responds: ‘Rejuvenate? I’m in a park and I’m practically dead? What good’s the countryside’.

Withnail and Marwood visit Withnail’s Uncle Monty, and Withnail manages to acquire the keys to Monty’s country retreat. Whilst staying at the country house, Withnail and Marwood struggle to communicate with the locals. In an early scene, they flee from a scrap in a London pub populated by urban working-class types; ironically, they see the countryside, which they initially perceived to be a place of retreat from the urban environment, as equally threatening, with Withnail in particular becoming increasingly panicked by the presence of a proletarian poacher (Michael Elphick). Likewise, they also discover that the urban squalor of their house in London has simply been swapped for the squalor of Monty’s cottage, which is in an equal – if not worse – state of disarray. Withnail and Marwood’s shared panic over their cultural ‘other’ (the working-classes, both urban and rural) is conflated into a panic surrounding homosexuality when Uncle Monty arrives at the country house and makes advances towards Marwood. It seems that Withnail acquired the keys for Uncle Monty’s cottage based on a promise that Marwood would sleep with Monty. (Monty, meanwhile, is under the assumption that Marwood and Withnail are lovers.) The pair decide to return to London, where Marwood receives a telegram informing him he’s been offered a job elsewhere. This is the catalyst he needs in order to sever his increasingly self-destructive friendship with Withnail.  Paul Dave has compared the film with Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970). Both films, Dave argues, are about the end of the 1960s and are ‘heavy with an atmosphere of countercultural decline and defeat’ (2006: 113). In Withnail & I, the sense of transition from one era to another is signaled visually when Withnail and Marwood begin to drive out of London and, as Jimi Hendrix’s cover of ‘All Along the Watchtower’ plays on the soundtrack, we are presented with shots of old back-to-back terraces being demolished. Monty foregrounds this theme when, after arriving at the cottage, he quotes Tennyson’s ‘Morte d’Arthur’ (‘The old order changeth, yielding place to new/And God fulfils Himself in many ways’) before telling Withnail and Marwood, ‘My boys, we’re at the end of an age. We live in a land of weather forecasts and breakfasts that “set in”. Shat on by Tories, shoveled up by Labour. And here we are. We three. Perhaps the last island of beauty in the world’. Even the constantly high drug dealer Danny (Ralph Brown) acknowledges this fin-de-siecle anxiety when he notes that ‘London is a country coming down from its trip. We are 91 days from the end of this decade and there’s going to be a lot of refugees’. Shortly after, he tells Marwood, ‘They’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworth’s, man. The greatest decade in the history of mankind is over. And, as Presuming Ed here has so consistently pointed out, we have failed to “paint it black”’. The theme of cultural transition, the threshold marking the end of the sixties (and the utopian ideas associated with the concept of ‘the sixties’), is explored through the end of Marwood’s relationship with Withnail; at the end of the film, we are left with the impression that Withnail, remarkable actor though he is (he leaves the screen after beautifully quoting Hamlet’s ‘What piece of work is a man’ soliloquy), will continue on his self-destructive path – but alone, without his friend to accompany him. Marwood, meanwhile, will return home and, moving into the future, moderate his aspirations to accommodate the reality of his surroundings. Paul Dave has compared the film with Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance (1970). Both films, Dave argues, are about the end of the 1960s and are ‘heavy with an atmosphere of countercultural decline and defeat’ (2006: 113). In Withnail & I, the sense of transition from one era to another is signaled visually when Withnail and Marwood begin to drive out of London and, as Jimi Hendrix’s cover of ‘All Along the Watchtower’ plays on the soundtrack, we are presented with shots of old back-to-back terraces being demolished. Monty foregrounds this theme when, after arriving at the cottage, he quotes Tennyson’s ‘Morte d’Arthur’ (‘The old order changeth, yielding place to new/And God fulfils Himself in many ways’) before telling Withnail and Marwood, ‘My boys, we’re at the end of an age. We live in a land of weather forecasts and breakfasts that “set in”. Shat on by Tories, shoveled up by Labour. And here we are. We three. Perhaps the last island of beauty in the world’. Even the constantly high drug dealer Danny (Ralph Brown) acknowledges this fin-de-siecle anxiety when he notes that ‘London is a country coming down from its trip. We are 91 days from the end of this decade and there’s going to be a lot of refugees’. Shortly after, he tells Marwood, ‘They’re selling hippie wigs in Woolworth’s, man. The greatest decade in the history of mankind is over. And, as Presuming Ed here has so consistently pointed out, we have failed to “paint it black”’. The theme of cultural transition, the threshold marking the end of the sixties (and the utopian ideas associated with the concept of ‘the sixties’), is explored through the end of Marwood’s relationship with Withnail; at the end of the film, we are left with the impression that Withnail, remarkable actor though he is (he leaves the screen after beautifully quoting Hamlet’s ‘What piece of work is a man’ soliloquy), will continue on his self-destructive path – but alone, without his friend to accompany him. Marwood, meanwhile, will return home and, moving into the future, moderate his aspirations to accommodate the reality of his surroundings.

In contrast with Performance’s celebration of androgyny and open sexuality, however, in Withnail & I ‘Performance’s androgyny, deconstructed genders and liberated sexuality becomes, in the later film, the panic-stricken affirmation of heterosexuality and exaggerated disgust at social difference’ (ibid.). Performance offers a ‘sinister vision of Old England’s class system’, whereas Withnail & I examines the moment at which ‘the bohemian class mixing of the 1960s falters and is replaced, at the end of the film, by a new, socially “decontaminated” aestheticism’ (ibid.).  Furthermore, where ‘the casting of Johnny Shannon and the acting of James Fox’ in Performance evoked a ‘sense [or presence] of the charismatic working class’, this is absent in Withnail & I, which focuses almost exclusively on various strata within the English middle class: Withnail & I ‘is concerned not with a mix in which the proletariat and countercultural bohemians threaten Old England’ (as depicted in Performance by the ambiguous relationship between James Fox and Mick Jagger’s characters) but rather ‘traces a process of middle-class disengagement from revolutionary politics and the re-establishment of a traditional English class landscape’ (ibid.). The two urban working class spaces depicted within the film, the ‘Wanker’s Café’ and the London pub that Marwood and Withnail visit, are painted by Marwood in his narration (and his onscreen behaviour) as places of threat and repulsion. Likewise, Withnail and Marwood are thrown into a similar panic when they encounter the various members of the rural working-class who live in the community in which Monty’s cottage is situated – especially the local poacher, who Withnail becomes convinced will make an attempt on his life. (Marwood acknowledges how wrong his expectations of country life were when, in his narration, he asserts, ‘Not the attitude I’d come to expect from the H E Bates novel I’d read. I thought they’d all be out and about, drinking cider, discussing butter. Evidently, country people are no more receptive to strangers than city dwellers’.) Furthermore, where ‘the casting of Johnny Shannon and the acting of James Fox’ in Performance evoked a ‘sense [or presence] of the charismatic working class’, this is absent in Withnail & I, which focuses almost exclusively on various strata within the English middle class: Withnail & I ‘is concerned not with a mix in which the proletariat and countercultural bohemians threaten Old England’ (as depicted in Performance by the ambiguous relationship between James Fox and Mick Jagger’s characters) but rather ‘traces a process of middle-class disengagement from revolutionary politics and the re-establishment of a traditional English class landscape’ (ibid.). The two urban working class spaces depicted within the film, the ‘Wanker’s Café’ and the London pub that Marwood and Withnail visit, are painted by Marwood in his narration (and his onscreen behaviour) as places of threat and repulsion. Likewise, Withnail and Marwood are thrown into a similar panic when they encounter the various members of the rural working-class who live in the community in which Monty’s cottage is situated – especially the local poacher, who Withnail becomes convinced will make an attempt on his life. (Marwood acknowledges how wrong his expectations of country life were when, in his narration, he asserts, ‘Not the attitude I’d come to expect from the H E Bates novel I’d read. I thought they’d all be out and about, drinking cider, discussing butter. Evidently, country people are no more receptive to strangers than city dwellers’.)

From the outset, the supposedly bohemian space in which Withnail and Marwood exist is depicted as one of squalor, and at the end of the film Marwood reacts angrily (in a very counter-counter-cultural manner) against the heterogeneity seen within the flat, ranting angrily about the dog-sized rats in the kitchen and the ‘huge spade’ (Presuming Ed) in his bathtub. Monty’s cottage in the Lake District, symbolic of the past and England’s rural identity, is no different: it too is a place of squalor and decay. Uncle Monty, who embodies the brand of upper middle-class dandy that tends to dominate depictions of England in the years between the two world wars, is a sexually voracious homosexual, against whose advances Marwood reacts angrily – in another display of the limits of the counterculture’s celebration of heterogeneity. However, Monty’s ‘gay lyricism has, with age, turned into a cover for priapic opportunism’ (Dave, op cit.: 114). (‘I mean to have you, even if it must be burglary’, Monty tells Marwood at one point.) Marwood, as a blank cipher (the ‘and I’ of the title) who is representative of the English middle-class, struggles to find his place within (and indeed reacts against) the urban bohemian set, Monty’s upper middle-class dandyism, and amongst the rural folk within the village community in which Withnail and Marwood go ‘on holiday by mistake’.  Robinson’s second film as director, How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1989), also began life as a novel and, like the film that preceded it, featured Richard E Grant in a leading role. However, How to Get Ahead in Advertising foregrounded the political subtext that had been present, in a more subtle way, in Withnail & I. In contrast with Withnail & I, How to Get Ahead in Advertising was intended to be ‘explicitly political’, Robinson’s exploration of ‘my perception of where the country is going’ (Davidson, 2013: 167). Robinson’s second film as director, How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1989), also began life as a novel and, like the film that preceded it, featured Richard E Grant in a leading role. However, How to Get Ahead in Advertising foregrounded the political subtext that had been present, in a more subtle way, in Withnail & I. In contrast with Withnail & I, How to Get Ahead in Advertising was intended to be ‘explicitly political’, Robinson’s exploration of ‘my perception of where the country is going’ (Davidson, 2013: 167).

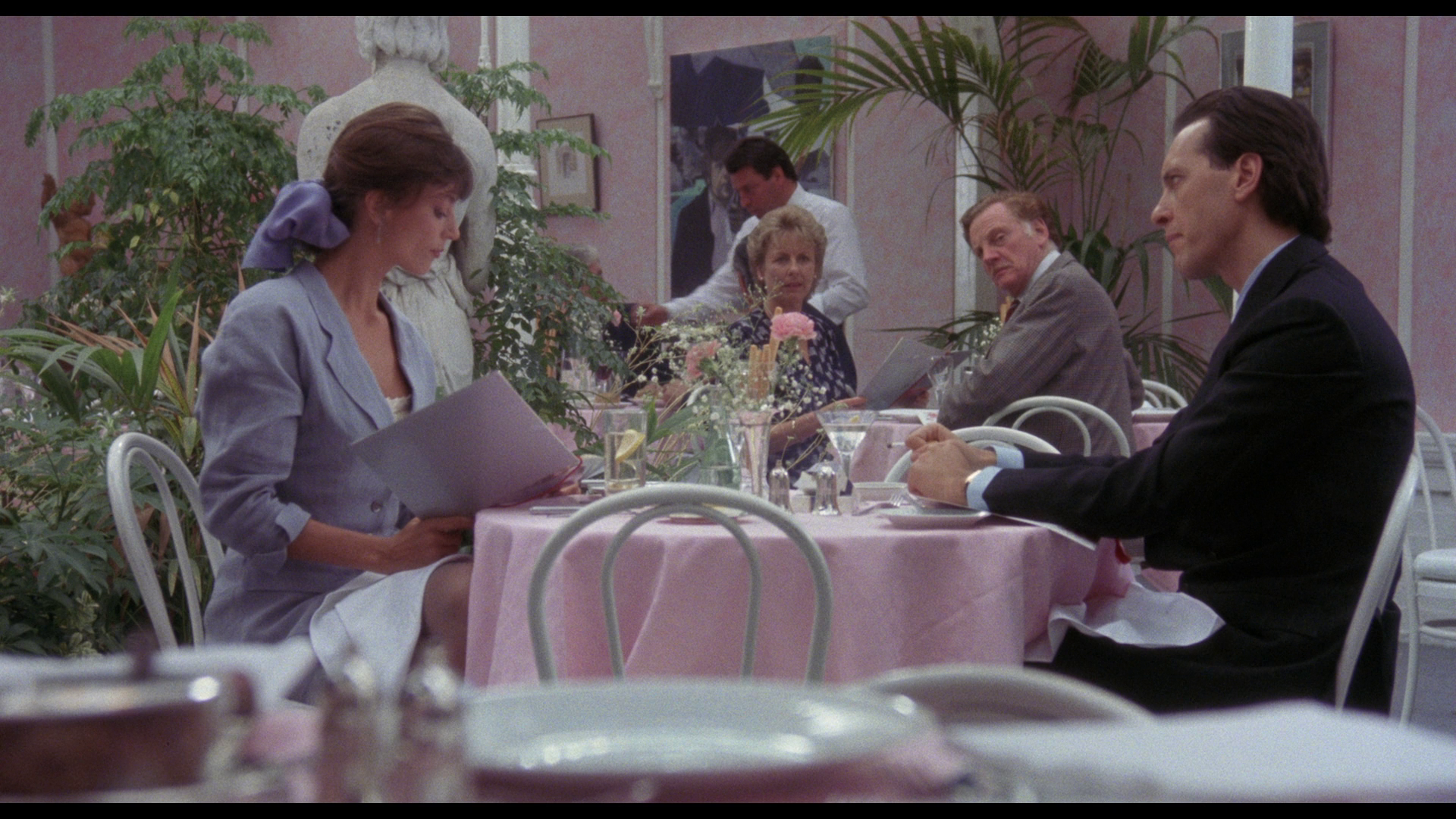

Grant plays Denis Dimbleby Bagley, an advertising executive who is tasked with producing a promotional campaign for a brand of pimple cream. A typical workaholic, Bagley faces a creative block which leads to an existential crisis. He quits his job, much to the chagrin of his wife Julia (Rachel Ward) and his boss John Bristol (Richard Wilson), and spends his time criticising the reification and commodity fetishism that takes place within modern consumer society. However, Bagley soon discovers that he is growing his own pimple: a boil appears on his shoulder. It’s fairly harmless at first, but soon it develops sight and then progresses to finding its own voice, regurgitating advertising slogans and abusing those close to Bagley. However, those around Bagley believe him to be experiencing some form of nervous exhaustion, and he is sent to see a psychiatrist. Admitted to a hospital, Bagley is prepped for surgery to remove the boil, which has dramatically increased in size. However, before the surgery takes place Bagley discovers that the boil has become a second head, and this head now takes control of Bagley’s body, wrapping Bagley’s ‘real’ head in bandages. The surgeons remove Bagley’s ‘real’ head, and Bagley’s body, commanded by the ‘boil’, returns to work in advertising. There, the new Bagley promotes the idea of advertising the pimple cream by first making boils seem sexy (thus making them a fashion accessory) – a first step towards making the new cream a necessity. However, the ‘real’ Bagley begins to resurface – this time as another boil.  Deviating from the devices Robinson employed in Withnail & I, however, How to Get Ahead in Advertising also references some of the tropes of the ‘body horror’ films that were popular throughout the 1980s – for example, David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982) and Brian Yuzna’s Society (1989). Barring its less overt use of humour, the latter film, with its dryly witty exploration of the exclusivity of social elites who belong to a different species and can change their bodies through the process of ‘shunting’, has a fair few similarities with How to Get Ahead in Advertising. The boil/second head that is grown by Bagley, which represents the ‘me first’ ethos that Bagley rejects when he gives up his job and in its constant regurgitation of advertising slogans is suggestive of the extent to which the discourse of advertising has come to colonise the ‘self’, has drawn comparisons to the relationship between Duane (Kevin Van Hentenryck) and his evil Siamese twin Belial in Frank Henenlotter’s cult American horror film Basket Case (1982). However, the imagery of the boil sprouting from Bagley’s neck and growing into a fully-formed head recalls the iconography within Lee Frost’s The Thing with Two Heads (1972) and Sam Raimi’s later picture Army of Darkness (1992) – notably the sequence in which ‘Evil Ash’ sprouts from Ash (Bruce Campbell). Deviating from the devices Robinson employed in Withnail & I, however, How to Get Ahead in Advertising also references some of the tropes of the ‘body horror’ films that were popular throughout the 1980s – for example, David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982) and Brian Yuzna’s Society (1989). Barring its less overt use of humour, the latter film, with its dryly witty exploration of the exclusivity of social elites who belong to a different species and can change their bodies through the process of ‘shunting’, has a fair few similarities with How to Get Ahead in Advertising. The boil/second head that is grown by Bagley, which represents the ‘me first’ ethos that Bagley rejects when he gives up his job and in its constant regurgitation of advertising slogans is suggestive of the extent to which the discourse of advertising has come to colonise the ‘self’, has drawn comparisons to the relationship between Duane (Kevin Van Hentenryck) and his evil Siamese twin Belial in Frank Henenlotter’s cult American horror film Basket Case (1982). However, the imagery of the boil sprouting from Bagley’s neck and growing into a fully-formed head recalls the iconography within Lee Frost’s The Thing with Two Heads (1972) and Sam Raimi’s later picture Army of Darkness (1992) – notably the sequence in which ‘Evil Ash’ sprouts from Ash (Bruce Campbell).

The film’s attack on Bagley’s profession is savage. As the film opens, Bagley, who promises ‘give me a bald head and I’d sell it shampoo’ and asserts ‘I’m the man who’s taken the stench out of everything except shit’, is shown delivering a presentation to a group of subordinates, offering him a chance to espouse his worldview. ‘Let me try and clarify some of this for you’, Bagley begins: ‘Best Company supermarkets are not interested in selling wholesome foods. They are not worried about the nation’s health. What is concerning them is that the nation appears to be getting worried about its health [….] because Best Co wants to go on selling them what it always has: ie, white breads, baked beams, canned foods and that suppurating, fat squirting little heart attack traditionall known as the “British sausage”. So, how can we help them with that?’ Advertising, in Bagley’s world, is devoid of morality: there is no code of ethics. The bottom line for Bagley, as the film opens, is embodied in the credo: ‘Whatever it is, sell it; and if you want to stay in advertising, by God you’d better learn that’. The pimple cream campaign poses a challenge because, as Bagley tells his wife, ‘Nobody in advertising wants to get rid of boils, Julia. They’re good little money-spinners. All we want to do is offer hope of getting rid of them. And that’s where I’m blocked’.  However, Bagley gradually develops a change of heart, with his bitterness and mercenary qualities becoming repressed and finding their expression through the boil that develops on his shoulder (a more overt example of the ‘return of the repressed’ would be difficult to find). On the train home for the weekend, Bagley argues with a group of passengers in his train carriage over a news story about a murder that appears to have been carried out over a bag containing cannabis resin (which may also have contained an amount of heroin). ‘The bag could have been full of anything’, Bagley interrupts: ‘Pork pies, turnips [….] It’s the oldest trick in the book’. ‘What book?’, a vicar asks. ‘The “distortion of truth by association” book’, Bagley responds, ‘The word is “may”. You all believe heroin was in the bag because cannabis resin was in the bag. The bag “may” have contained heroin. But the chances are one hundred to one certain that it didn’t’. When his authority is questioned, Bagley tells his fellow passengers, ‘I’m also an expert drug pusher. I’ve been pushing drugs for twenty years [….] And I can tell you, a pusher protects his patch. We wanna sell them cigarettes; we don’t like competition, see. So we associated a relatively innocuous drug [cannabis] with one that is extremely dangerous [heroin]. And the rags go along with it ‘cause they love the dough from the ads’. This thread is alluded to later on in the film, when Bagley resigns from his job with the advertising agency for which he works. Storming into Bristol’s office, Bagley cites as one of his reasons for leaving a campaign he devised for government’s anti-smoking drive, which was sidelined in favour of the softer ‘smoking can seriously damage your health’. Bagley’s campaign associated smoking more closely with death, and as Bagley asserts, ‘The only fucker this [the poster he designed] ever frightened was the Chancellor of the Exchequer’. However, Bagley gradually develops a change of heart, with his bitterness and mercenary qualities becoming repressed and finding their expression through the boil that develops on his shoulder (a more overt example of the ‘return of the repressed’ would be difficult to find). On the train home for the weekend, Bagley argues with a group of passengers in his train carriage over a news story about a murder that appears to have been carried out over a bag containing cannabis resin (which may also have contained an amount of heroin). ‘The bag could have been full of anything’, Bagley interrupts: ‘Pork pies, turnips [….] It’s the oldest trick in the book’. ‘What book?’, a vicar asks. ‘The “distortion of truth by association” book’, Bagley responds, ‘The word is “may”. You all believe heroin was in the bag because cannabis resin was in the bag. The bag “may” have contained heroin. But the chances are one hundred to one certain that it didn’t’. When his authority is questioned, Bagley tells his fellow passengers, ‘I’m also an expert drug pusher. I’ve been pushing drugs for twenty years [….] And I can tell you, a pusher protects his patch. We wanna sell them cigarettes; we don’t like competition, see. So we associated a relatively innocuous drug [cannabis] with one that is extremely dangerous [heroin]. And the rags go along with it ‘cause they love the dough from the ads’. This thread is alluded to later on in the film, when Bagley resigns from his job with the advertising agency for which he works. Storming into Bristol’s office, Bagley cites as one of his reasons for leaving a campaign he devised for government’s anti-smoking drive, which was sidelined in favour of the softer ‘smoking can seriously damage your health’. Bagley’s campaign associated smoking more closely with death, and as Bagley asserts, ‘The only fucker this [the poster he designed] ever frightened was the Chancellor of the Exchequer’.

Aside from its satirical approach to the world of advertising, How to Get Ahead in Advertising offers an interesting take on identity which seems to side with the centralism that is often promoted by films based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: that identity resides within the brain (or head). Bagley’s boil develops into a second head that takes control of Bagley’s body. Meanwhile, the ‘real’ Bagley resurfaces after being removed by the surgeons and then repressed within Bagley’s body, to once again take control of his own self. ‘My head. You’re going to lance the wrong…’, screams Bagley as the surgery to remove his boil is prepped and he realises that the boil intends to have Bagley’s head removed. The film offers a critique of the ‘me’ generation and its prominence during the 1980s: it’s often taken as an attack on Thatcher’s Britain, but in terms of its assault on marketing, chauvinism, boardroom politics and the notion of ‘me first’ culture, the film has corollaries within American culture - for example, Neil LaBute’s vitriolic picture about boardroom exploitation, In the Company of Men (1997), Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho (1989) or even, arguably, the highly-regarded television series Mad Men (AMC, 2007-15). How to Get Ahead in Advertising has also been compared with earlier films which satirised the advertising ‘industry’, such as The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (Nunnally Johnson, 1956), Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, 1957) and The Hucksters (Jack Conway, 1947).  At times, the acerbic script becomes heavily polemical, perhaps a little guilty of stating its themes in a manner that is quite didactic. This is the case when Bagley, his head covered with a wine carton so as not to wake the boil, records a video diary for Julia. ‘The world is in danger’, Bagley asserts, ‘The greed is out of control. Reed is abolishing the future, It’s turning truth inside out and upside down. And this [he taps the lens of the video camera he’s using to record his rant] is its poisonous mouthpiece’. Later, Bagley visits a psychiatrist and, in a direct critique of television, offers his reasons for resigning from the advertising world: ‘Reason one’, he says, is that ‘advertising conspires with Big Brother’ to monitor our daily lives and, through market research, gather information about us. ‘The man who conceived of Big Brother [Orwell] thought his filthy creation was going to be watching us’, Bagley continues, ‘but it is us who watch it. There is one in every living room. The monstrous injustice of it is: we stare at it of our own free will’. At times, the acerbic script becomes heavily polemical, perhaps a little guilty of stating its themes in a manner that is quite didactic. This is the case when Bagley, his head covered with a wine carton so as not to wake the boil, records a video diary for Julia. ‘The world is in danger’, Bagley asserts, ‘The greed is out of control. Reed is abolishing the future, It’s turning truth inside out and upside down. And this [he taps the lens of the video camera he’s using to record his rant] is its poisonous mouthpiece’. Later, Bagley visits a psychiatrist and, in a direct critique of television, offers his reasons for resigning from the advertising world: ‘Reason one’, he says, is that ‘advertising conspires with Big Brother’ to monitor our daily lives and, through market research, gather information about us. ‘The man who conceived of Big Brother [Orwell] thought his filthy creation was going to be watching us’, Bagley continues, ‘but it is us who watch it. There is one in every living room. The monstrous injustice of it is: we stare at it of our own free will’.

To some extent, the film’s criticisms of television seem to conform to the traditional snobbery exhibited within cinema towards the newer medium of television – in Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) or Medium Cool (Haskell Wexler, 1969), for example. As if to foreground the film’s own incoherence in terms of its exploration of this theme (ie, its employment of the very techniques associated with that which it satirises), when Bagley tells Bristol that he is resigning and plans to tell the world about the inherent evil of advertising, Bristol asks Bagley how he intends to do this, by sandwich board perhaps? As Bristol reminds Bagley, this is itself a form of advertising. In one of the great resignation scenes from film history, Bagley then threatens to resign from his job, and Bristol suggests he ‘take some time off’. ‘What the fuck do you think I’m resigning for?’, Bagley asks, ‘I’m taking forever off!’ Then Bagley proceeds to inform Bristol, ‘I tell you, Bristol. Any night here, I’m bound to turn up here and burn this dump to the ground’.

Video

For anyone whose first viewing of Withnail & I may have been on VHS, watching the film on that format would seem to confirm Bruce Robinson’s (ironic?) assertion that the film is ‘a badly shot film with great dialogue’. (This is a comment Robinson repeats in Channel 4’s 1999 ‘Withnail & Us’ featurette that’s included on this disc as an ‘extra’.) However, seeing the film at a cinema in the late-1990s gave me a different perspective on it: the photography, from the opening shots of a reflective Marwood at home in the flat to the sequences depicting Marwood and Withnail’s experiences in the English countryside, is actually pretty strong in places, but it’s just been poorly served by disappointing home video versions (the various VHS releases and, later, DVD releases). For anyone whose first viewing of Withnail & I may have been on VHS, watching the film on that format would seem to confirm Bruce Robinson’s (ironic?) assertion that the film is ‘a badly shot film with great dialogue’. (This is a comment Robinson repeats in Channel 4’s 1999 ‘Withnail & Us’ featurette that’s included on this disc as an ‘extra’.) However, seeing the film at a cinema in the late-1990s gave me a different perspective on it: the photography, from the opening shots of a reflective Marwood at home in the flat to the sequences depicting Marwood and Withnail’s experiences in the English countryside, is actually pretty strong in places, but it’s just been poorly served by disappointing home video versions (the various VHS releases and, later, DVD releases).

This Blu-ray (whose transfer derives from a new 2K master that was restored with the supervision and approval of the film’s director of photography, Peter Hannan) offers a welcome alternative, and contains an impressive presentation of the film (in 1080p, and using the AVC codec). It is by far the best presentation Withnail & I has had to date. Low light sequences set at night-time (of which there are many) have the strong, defined grain structure of ‘pushed’ film. Daytime sequences have a more refined structure. The contrast between the texture of the daytime shots and the night-time sequences is noticeable but true to the original photography. The presentation throughout has a remarkably organic, film-like ‘look’ to it, unlike the previous home video versions; this is bolstered by good contrast, which serves to remedy the ‘flatness’ of most previous home video versions. The film is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio and, running for 107:24 mins, is uncut. How to Get Ahead in Advertising is also presented in the 1.85:1 ratio, and again the presentation is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. How to Get Ahead in Advertising has a shorter running time of 93:58. The presentation is good but not quite as strong as that for Withnail & I. The presentation has a natural, organic aesthetic, with good contrast and a strong level of detail within the image. It’s a significant step up from the DVD releases, including the DVD released by Criterion in the US. NB. Larger screen grabs from both films are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Both films are presented (in English) with LPCM tracks. Withnail & I’s audio track is in single-channel mono, whilst the audio track for How to Get Ahead in Advertising is in 2.0 stereo. Both tracks are fine, but thanks to its use of music Withnail’s track is more interesting and, in terms of the dynamic range facilitated by its lossless presentation, more ‘showy’. In this sense, it’s a big improvement over the lossy audio contained on the film’s various DVD releases. How to Get Ahead in Advertising’s sound mix, on the other hand, is more predicated and dialogue and the lossless track only really gets a workout when Richard E Grant’s performance turns ‘shouty’ – which, on reflection, is quite regularly, to be honest. Both films contain optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The Withnail & I disc includes an array of contextual material, including: The Withnail & I disc includes an array of contextual material, including:

- two audio commentaries, one by director Bruce Robinson (recorded in 2009 and available on previous releases); and the other by Kevin Jackson (recorded this year, and new to this release), who wrote the monograph on Withnail & I that was published as part of the BFI’s Modern Classics range. - a series of short documentaries from Channel 4’s Withnail Weekend, broadcast in 1999. These feature interviews with the likes of Bruce Robinson, Richard E Grant, Ralph Brown, Paul McGann, James Brown (then-of GQ magazine) and Adam Buxton and Joe Cornish, along with a range of fans of the film: -- ‘Withnail and Us’ (25:01). This focuses on the enduring appeal of the film and features interviews with some of its cast and crew, alongside comments by fans of the film. -- ‘The Peculiar Memories of Bruce Robinson’ (38:56). Robinson reflects on the genesis of the picture and his feelings towards it. -- ‘I Demand to Have Some Booze!’ (6:00). This focuses on the Withnail & I drinking game and features a group of late-90s university types practicing it. (Richard E Grant prays that no-one dies from taking part in this notorious challenge.) -- ‘Withnail on the Pier’ (4:25). This short piece focuses on a screening of the film on Brighton pier and features comments from the film’s fans. - ‘An Appreciation by Sam Bain’ (8:04). Comedy writer Bain, one of the creators of Channel 4’s Peep Show, explains his love of Withnail & I. - ‘Interview with Michael Pickwoad’ (21:13), the film’s production designer. - the film’s theatrical trailer (1:26). How to Get Ahead in Advertising has a smaller range of contextual material, including: - another ‘Interview with Michael Pickwoad’ (10:11), in which the production designer talks about his work on the film; and - the film’s original trailer (1:53).

Overall

Withnail & I is as brilliantly funny as it ever was – but it’s a low-key, bittersweet brand of humour. The dialogue is incredibly sharp: at one point, Danny tells Withnail and Marwood that he intends to go into business making dolls – Presuming Ed ‘got a doll for Christmas what pisses itself. You got to change its drawers for it and all [….] It’s horrible, really. But they like that, little girls. So we’re gonna make one that shits itself as well’. How to Get Ahead in Advertising is more overtly and directly ‘political’ (and, probably not by coincidence, it’s also more outrageously – almost desperately – comedic); but both films have much to say about the state of Britain in the 1980s (and its relationship with the utopian ideals/representations of the 1960s). Withnail & I’s areas of contrast with Cammell and Roeg’s Performance are, in this regard, telling. Withnail & I is as brilliantly funny as it ever was – but it’s a low-key, bittersweet brand of humour. The dialogue is incredibly sharp: at one point, Danny tells Withnail and Marwood that he intends to go into business making dolls – Presuming Ed ‘got a doll for Christmas what pisses itself. You got to change its drawers for it and all [….] It’s horrible, really. But they like that, little girls. So we’re gonna make one that shits itself as well’. How to Get Ahead in Advertising is more overtly and directly ‘political’ (and, probably not by coincidence, it’s also more outrageously – almost desperately – comedic); but both films have much to say about the state of Britain in the 1980s (and its relationship with the utopian ideals/representations of the 1960s). Withnail & I’s areas of contrast with Cammell and Roeg’s Performance are, in this regard, telling.

The dialogue in both films is witty and has elements of profundity: in Withnail & I, Grant’s delivery of Shakespeare’s ‘What a piece of work is man’ speech is eloquent (and worth comparing with the very different interpretation of the speech that was delivered by Patrick Stewart in the first season episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, ‘Hide and Q’, that was broadcast the same year as Withnail & I’s release, 1987). Danny’s monologue, towards the end of the film, about the dilemma of one who is hanging on to a rising balloon has a level of significance within the film (as a metaphor for Marwood’s relationship with Withnail, and what that could be said to represent) but also has a wider cultural significance: ‘Politics, man’, Danny tells Marwood, ‘If you're hanging onto a rising balloon, you're presented with a difficult decision: let go before it's too late or hang on and keep getting higher, posing the question: how long can you keep a grip on the rope?’  In his contemporary review of How to Get Ahead in Advertising, David Denby compared Richard E Grant’s ability to ‘rant and rave and hiss’ in a way that shows ‘us how witty tirade-acting can be’ to James Woods’ performances (especially in True Believer) (1989: 71). He also suggested similarities between Grant and ‘hyper-articulate English actor[s]’ Dirk Bogarde and Alan Bates, in terms of Grant’s ability to conjure up disgust (at the sausages and housewives mentioned in Bagley’s opening monologue, for example) (ibid.: 72). Both Withnail & I and How to Get Ahead in Advertising offer Grant the ability to practise this element of his screen persona. However, in Withnail & I McGann’s relatively low-key performance offers a foil for the excesses of Richard E Grant’s performance as Withnail. This is lacking in How to Get Ahead in Advertising, which is resolutely Grant’s film. Perhaps in reaction to these excesses, Robinson’s next film as a director (and his final till 2011’s Hunter Thompson adaptation The Rum Games) was the fairly conventional Hollywood thriller Jennifer Eight (1992). In his contemporary review of How to Get Ahead in Advertising, David Denby compared Richard E Grant’s ability to ‘rant and rave and hiss’ in a way that shows ‘us how witty tirade-acting can be’ to James Woods’ performances (especially in True Believer) (1989: 71). He also suggested similarities between Grant and ‘hyper-articulate English actor[s]’ Dirk Bogarde and Alan Bates, in terms of Grant’s ability to conjure up disgust (at the sausages and housewives mentioned in Bagley’s opening monologue, for example) (ibid.: 72). Both Withnail & I and How to Get Ahead in Advertising offer Grant the ability to practise this element of his screen persona. However, in Withnail & I McGann’s relatively low-key performance offers a foil for the excesses of Richard E Grant’s performance as Withnail. This is lacking in How to Get Ahead in Advertising, which is resolutely Grant’s film. Perhaps in reaction to these excesses, Robinson’s next film as a director (and his final till 2011’s Hunter Thompson adaptation The Rum Games) was the fairly conventional Hollywood thriller Jennifer Eight (1992).

Both films get very good presentations in this set, with the new restoration of Withnail & I being particularly impressive and eclipsing the previously-available Blu-rays – but the presentation of How to Get Ahead in Advertising is no slouch either. The rich array of contextual material (retail copies of the set also come with a lavish book), in relation to Withnail & I, is impressive; but it perhaps would have been nice to see a few more reflections on Robinson’s second film as director. In sum, this is a very impressive release, and the legions of fans of Withnail & I should be very pleased with it. References: Dave, Paul, 2006: Visions of England: Class and Culture in Contemporary Cinema. London: Berg Davidson, Martin P, 2013: The Consumerist Manifesto: Advertising in Postmodern Times. London: Routledge Denby, David, 1989: ‘The Realm of the Senses’. New York Magazine (22 May, 1989): 71-3 Ebert, Roger, 2010: The Great Movies III. University of Chicago Press Hewitt-McManus, Thomas, 2006: Withnail & I: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know But Were Too Drunk to Ask. London: Lulu Press Inc MacKinnon, Kenneth, 1992: The Politics of Popular Representation: Reagan, Thatcher, AIDs, and the Movies. Farleigh Dickinson University Press Withnail & I

How to Get Ahead in Advertising

|

|||||

|