|

|

Killers (The) AKA Ernest Hemingway's The Killers (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th December 2014). |

|

The Film

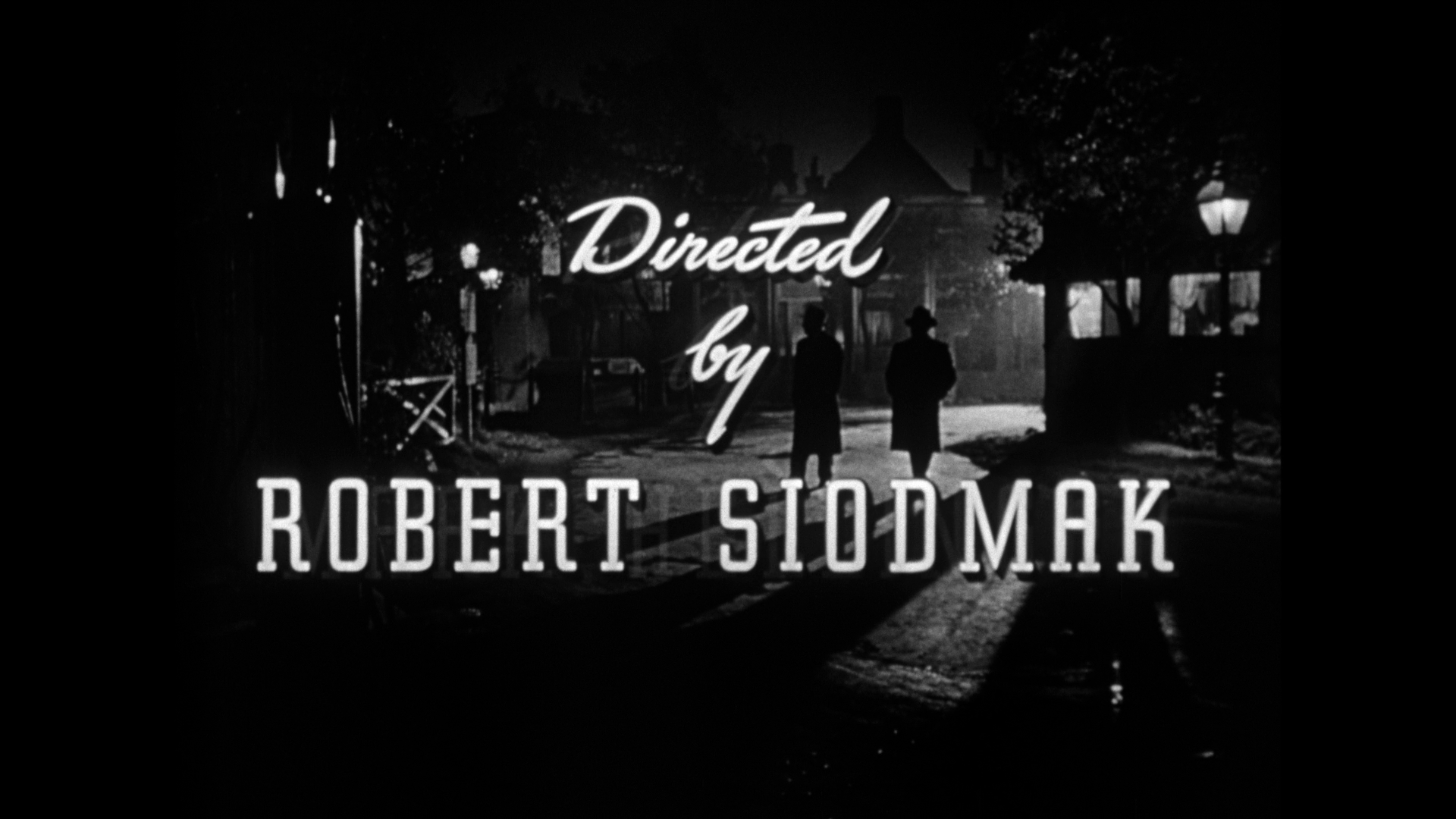

The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946) The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946)

First published in Scribner’s magazine in 1927 (and subsequently, in the anthology Men Without Women), Ernest Hemingway’s short story ‘The Killers’ is a benchmark of American hard-boiled writing. Set in Summit, Illinois, during the Prohibition era, ‘The Killers’ tells an ostensibly very simple story of two enigmatic hit-men who come from Chicago and terrorise the employees in a small-town diner (young Nick; middle-aged George, the diner’s owner; and African-American cook Sam). The titular killers are there to ‘hit’ Ole Andreson, known as ‘the Swede’, a former boxer with a mysterious past who now works in the town’s gas station. When the killers decide to journey to Mrs Hirsch’s boarding house, where Andreson lives, young Nick takes a more direct route through the gardens of the town, in an attempt to reach Andreson ahead of the killers and warn him of their impending arrival. However, upon reaching Andreson’s lodgings, Nick discovers the Swede lying on his bed in his cell-like room, resigned to his fate, insisting that there is nothing that can be done: the killers, and death, will catch up with him. Nick leaves the Swede alone, the arrival of the killers and the death of Andreson a certainty. The short story is one of a series of stories that Hemingway wrote about the character of Nick Adams, with each story taking place at a pivotal stage in Adams’ life. ‘The Killers’ is a story that focuses on Adam’s journey from adolescence to adulthood, Andreson’s resigned attitude towards his fate an event that makes Nick cognisant of the concept of death and its inevitability for us all. The Nick Adams stories generally, Philip Young has said, are stories ‘of an initation, […] the telling of an event […] which brings the boy into contact with something that is perplexing and unpleasant’ (quoted in Letort, 2013: 63). The killers themselves are depicted as semi-comic: their back-and-forth discussion about the diner’s menu compliments the description of them as ‘like a vaudeville team’ wearing ‘tight overcoats and derby hats’. They goad George by asking if he has ‘anything to drink’. ‘Silver beer, bevo, ginger-ale’, George tells them. ‘I mean you got anything to drink?’, they ask insistently, reminding the reader of the story’s setting during the Prohibition era. The diner itself is a former saloon with a ‘mirror that ran along back of the lunch counter’; the story begins in this space, a former drinking establishment that is invaded by two figures who are symbolic of Chicago and its association with illegal bootlegging, and ends in the tight space of Andreson’s lodgings. It’s a story defined by a claustrophobic sense of space, only venturing outside when Nick runs from the diner to Mrs Hirsch’s lodging house.  Surprisingly, given his association with the hard-boiled movement within American culture, ‘The Killers’ was the only Hemingway short story to be adapted as a film noir (see Letort, op cit.: 55). Additionally, as Siodmak once boasted, The Killers was ‘the only film of a Hemingway story that Hemingway actually likes! (We gave him a print of the film and I know that he has run it over 200 times)’ (quoted in Dickos, 2002: 35). What Siodmak neglected to mention was that when Hemingway ran the film for visitors to his Cuban home, ‘he invariably fell asleep after the first reel’ depicting the build-up to Andreson’s murder (Phillips, 2012: 141). The film’s script was written by Richard Brooks and Anthony Veiller, with uncredited input from John Huston. The film represents a marriage of the flashback structure that had been seen in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944) with a recurring leitmotif that can be seen in Huston’s films of the era: a focus on the aftermath of a heist (a narrative trope which had featured in Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, 1941, and would reappear in The Asphalt Jungle, 1950). Surprisingly, given his association with the hard-boiled movement within American culture, ‘The Killers’ was the only Hemingway short story to be adapted as a film noir (see Letort, op cit.: 55). Additionally, as Siodmak once boasted, The Killers was ‘the only film of a Hemingway story that Hemingway actually likes! (We gave him a print of the film and I know that he has run it over 200 times)’ (quoted in Dickos, 2002: 35). What Siodmak neglected to mention was that when Hemingway ran the film for visitors to his Cuban home, ‘he invariably fell asleep after the first reel’ depicting the build-up to Andreson’s murder (Phillips, 2012: 141). The film’s script was written by Richard Brooks and Anthony Veiller, with uncredited input from John Huston. The film represents a marriage of the flashback structure that had been seen in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944) with a recurring leitmotif that can be seen in Huston’s films of the era: a focus on the aftermath of a heist (a narrative trope which had featured in Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, 1941, and would reappear in The Asphalt Jungle, 1950).

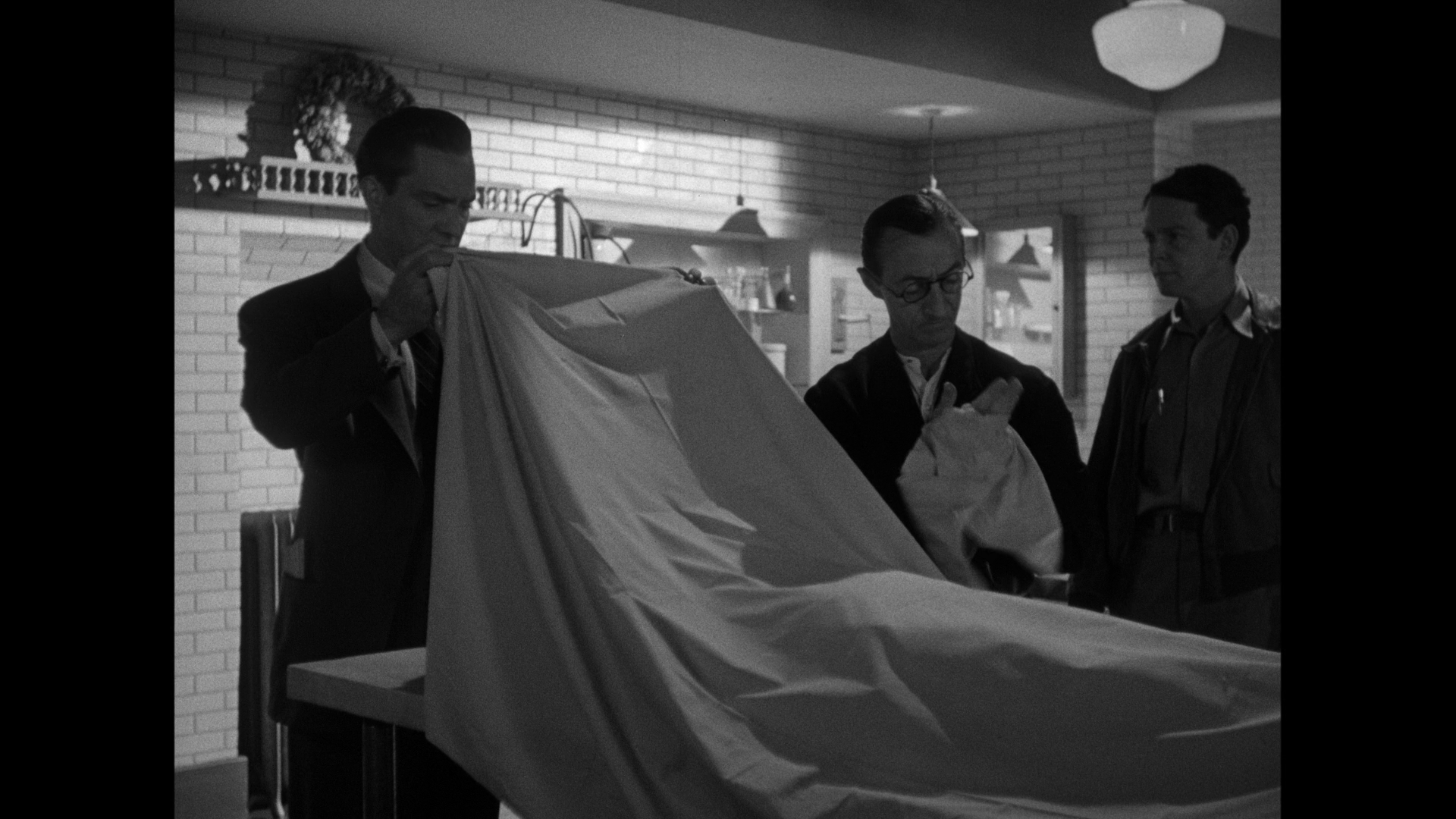

Hemingway’s story has been adapted for the screen a number of times: aside from Siodmak’s version, the story formed the basis for Don Siegel’s 1964 film The Killers (interestingly, Siegel was originally intended to direct the Siodmak adaptation in 1946), and a number of short film adaptations, the most famous of which is Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1956 student film (arguably the closest attempt to adapt Hemingway’s prose). Siodmak’s version of The Killers uses the events depicted with the short story, which are contained within then film’s opening fifteen minutes, as a springboard for a much larger narrative: the focus in Siodmak’s film is on the Swede, Ole Andreson (Burt Lancaster), who in the film also goes by the name of Pete Lung. After a sequence that closely follows the action within Hemingway’s source story, Lung’s assassination – by Max (William Conrad) and Al (Charles McGraw), the titular killers – is depicted on screen and followed by the investigation of an agent for an insurance company, Jim Reardon (Edmond O’Brien): the sole beneficiary of the Swede’s insurance policy, covered by his employer, is Mary Ellen Daugherty (Queenie Smith). Daugherty, Reardon discovers, has no relation to the Swede at all, other than the fact that a number of years earlier, she met him briefly in the hotel where she works as a maid and persuaded him not to commit suicide after she found him in his room screaming ‘She’s gone!’ before threatening to jump out of a window. Reardon’s only physical clue is a ‘green handkerchief decorated with golden harps’, and armed with this and the discovery that the Swede, under his real name of Ole Andreson, was a former prizefighter who served three years in prison for armed robbery, Reardon decides to interview the policeman who arrested Andreson, Detective Lieutenant Sam Lubinsky (Sam Levene).  Speaking with Lubinsky, Reardon discovers that Andreson and Lubinsky were from the same neighbourhood, and had in fact been childhood friends. ‘Ole and I ran around together when we were kids’, Lubinsky says. ‘And you put the pinch on him?’, Reardon asks. ‘When you’re a copper, you’re a copper’, Lubinsky answers gnomically. Lubinsky tells Reardon that Andreson had to give up his career as a boxer after shattering the bones in his right hand during a fight with Tiger Lewis in 1927. This led to Andreson’s world collapsing: ‘Last time there were fifty guys outside, just waitin’ to shake this [his broken right hand]’, Andreson observes when leaving the locker room after his disastrous fight with Lewis, ‘Funny when you lose a fight, ain’t it?’ In his despair, Andreson turns away his girl, Lilly (Virginia Christine), who it is revealed eventually married Lubinsky. Lilly tells Reardon that her relationship with Andreson ended when Andreson began to ‘go into business’ with a shady character, Big Jim Colfax (Albert Dekker), and started to make goo-goo eyes over Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner). There’s a wonderful shot, staged in depth, in which Kitty, gazing off-screen at a party, is in the foreground; Andreson is in the mid-ground, gazing longingly at Kitty; and Lilly is in the background, rendered small and insignificant by the composition, gazing jealously at Andreson. ‘Right then I knew the boat had sailed’, Lilly tells Reardon. Speaking with Lubinsky, Reardon discovers that Andreson and Lubinsky were from the same neighbourhood, and had in fact been childhood friends. ‘Ole and I ran around together when we were kids’, Lubinsky says. ‘And you put the pinch on him?’, Reardon asks. ‘When you’re a copper, you’re a copper’, Lubinsky answers gnomically. Lubinsky tells Reardon that Andreson had to give up his career as a boxer after shattering the bones in his right hand during a fight with Tiger Lewis in 1927. This led to Andreson’s world collapsing: ‘Last time there were fifty guys outside, just waitin’ to shake this [his broken right hand]’, Andreson observes when leaving the locker room after his disastrous fight with Lewis, ‘Funny when you lose a fight, ain’t it?’ In his despair, Andreson turns away his girl, Lilly (Virginia Christine), who it is revealed eventually married Lubinsky. Lilly tells Reardon that her relationship with Andreson ended when Andreson began to ‘go into business’ with a shady character, Big Jim Colfax (Albert Dekker), and started to make goo-goo eyes over Kitty Collins (Ava Gardner). There’s a wonderful shot, staged in depth, in which Kitty, gazing off-screen at a party, is in the foreground; Andreson is in the mid-ground, gazing longingly at Kitty; and Lilly is in the background, rendered small and insignificant by the composition, gazing jealously at Andreson. ‘Right then I knew the boat had sailed’, Lilly tells Reardon.

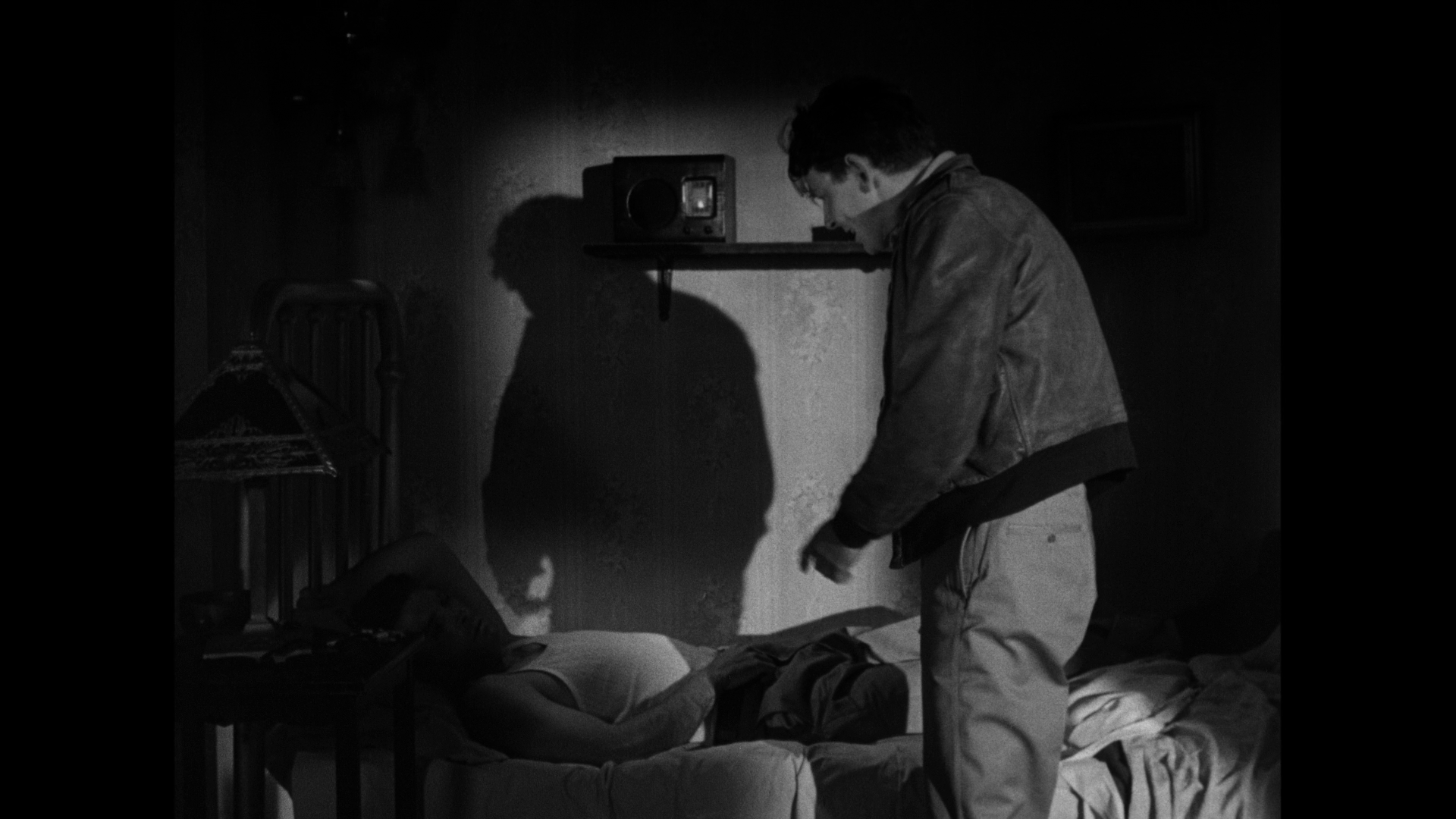

Reardon subsequently gathers further clues through an interview with Andreson’s former cellmate, Charleston (Vince Barnett); the deathbed confession of hoodlum ‘Blinky’ Franklin (Jeff Corey, in a scene reputedly inspired by the legendary deathbed confession of gangster Dutch Schultz); an at-gunpoint conversation with ‘Dum-Dum’ Clarke (Jack Lambert), another member of Big Jim Colfax’s gang; and further conversations with both Kitty Collins and Colfax himself. Reardon discovers that Andreson became involved in a heist at the Prentiss Hat Factory which resulted in $254,912 being stolen. Convinced by Kitty that he was to be double-crossed by the other members of Colfax’s gang, Andreson staged his own double-cross and, holding Colfax, ‘Dum Dum’ and ‘Blinky’ at gunpoint, stole the quarter of a million dollars from them. Now, Reardon must seek to discover what happened to the stolen money. Within the opening moments, the film ‘opens up’ the action contained within the short story, depicting the killers’ (Charles McGraw and William Conrad) arrival in the small town (here, Brentwood, rather than Summit): from within their car, we see them hurtling towards Brentwood and then, once they have arrived, making their way towards the diner. (By contrast, the short story is focalised entirely through the perspectives of George, Nick and, to a lesser extent, Sam.) Here, the comic elements associated with the killers have been all but removed: they don’t resemble the vaudeville characters alluded to within Hemingway’s story and are more overtly menacing. Also lost are the connections with the Prohibition era (which, of course, ended in 1933). This opening sequence climaxes with Nick’s journey to the Swede’s room, and the Swede’s resigned declaration, ‘There’s nothing I can do about it [….] There ain’t anything to do [….] I’m through with all that runnin’ around’. Where Hemingway’s story returns with Nick to the diner (where Nick reveals to George and Sam his decision to leave Summit), Siodmak’s film stays with the Swede and shows his death at the hands of the killers (depicted symbolically via a close-up of Lancaster’s hand sliding down the bedpost). Whereas Hemingway’s story is about the character of Nick and his realisation of the harsh brutality that exists within the world, in Siodmak’s adaptation Nick is little more than a narrative agent whose function is to introduce the Swede. The rest of the film follows Jim Reardon as he interviews various people who knew the Swede, to establish the meaning behind Andreson’s enigmatic response to Nick’s question ‘Why did they want to kill you?’: ‘Because I did something wrong… once’.  Andrew Dickos argues that the scene depicting the Swede’s execution, with the symbolic shot of his hand sliding down the bedpost, is ‘a poetic moment in American noir cinema, one that expresses all the existential elements of death and finality that would be discussed in every future discussion of the genre’ (op cit.: 36). Andreson’s response to Nick’s query, ‘Because I did something wrong… once’, refers not to the ‘violence and theft’ of which the subsequent investigation reveals him to be guilty, ‘but much more of the pain of self-betrayal’ enacted through ‘allowing himself to fall in love with Kitty Collins in the commission of such acts’ (ibid.: 39). Following the Swede’s death, Reardon’s investigation reveals a narrative that follows one of the dominant paradigms within many films noir of the 1940s – including Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945) and Tay Garnett’s adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) – which focus on ‘a man [who] falls hopelessly in love with the spouse of a man engaged in illicit activity. Out of love and devotion he buys his way into sleaze in order to gain the services of the woman who eventually doublecrosses him in fidelity to herself and her husband’ (Conley, 2000: 196). Andrew Dickos argues that the scene depicting the Swede’s execution, with the symbolic shot of his hand sliding down the bedpost, is ‘a poetic moment in American noir cinema, one that expresses all the existential elements of death and finality that would be discussed in every future discussion of the genre’ (op cit.: 36). Andreson’s response to Nick’s query, ‘Because I did something wrong… once’, refers not to the ‘violence and theft’ of which the subsequent investigation reveals him to be guilty, ‘but much more of the pain of self-betrayal’ enacted through ‘allowing himself to fall in love with Kitty Collins in the commission of such acts’ (ibid.: 39). Following the Swede’s death, Reardon’s investigation reveals a narrative that follows one of the dominant paradigms within many films noir of the 1940s – including Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945) and Tay Garnett’s adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) – which focus on ‘a man [who] falls hopelessly in love with the spouse of a man engaged in illicit activity. Out of love and devotion he buys his way into sleaze in order to gain the services of the woman who eventually doublecrosses him in fidelity to herself and her husband’ (Conley, 2000: 196).

The film is in many ways a distillation of the dominant paradigms of American films noir; and as Kitty Collins, who lures Andreson in to Colfax’s gang, Ava Gardner embodies the archetypal femme fatale. The overlapping flashbacks – what Foster Hirsch has called ‘like boxes within boxes’ (1981: 118) – that detail the events narrated to Reardon by his interviewees during the course of his investigation, eleven in all, point towards Collins’ role at the centre of the narrative – and her responsibility for Andreson’s decision to go on the lam, hiding out in Brentwood for several years, before finding his end at the gun barrels of Max and Al. This structure, Hirsch argues, suggests that ‘the past is often a maze that has to be penetrated, its mysteries uncovered only gradually, by means of a complex web of intersecting viewpoints’ (ibid.). Max and Al, as agents of Colfax’s will, are ruthless in the execution of their duty, awakening Brentwood to a new level of brutality. ‘I tell you what’s gonna happen: we’re gonna kill the Swede’, Al tells George during their conversation in the diner. ‘What’d Pete Lung ever do to you?’, Georeg asks. ‘Never had the chance to do anything to us. Never even seen us’, Max responds. Andreson’s death during the opening sequence means that the film’s resolution is stated at the outset: there’s no mystery surrounding what will happen to the Swede. As Andrew Spicer has noted, the film is dominated by an ‘inescapable spiral of destruction that characterizes Siodmak’s fatalistic romanticism’ (2014: 143).

Video

Dickos suggests that Siodmak was the first director associated with film noir ‘to appreciate the complementary value of a sympathetic cinematographer’, in this case Elwood ‘Woody’ Bredell. Siodmak and Bredell had first worked together on Siodmak’s Cornell Woolrich adaptation, Phantom Lady (1944). Bredell made a conscious decision to ‘cut back drastically on lighting, limiting the number of arc lamps for night scenes and foregoing fill light in others’ (Eagan, 2010: 396). The photography throughout the film is excellent: for example, the impeccably staged high-angle long shot which depicts the heist at the Prentiss Hat Factory in a long uninterrupted take. Recurring visual motifs within the film include shots of the Swede lying on beds (constantly recalling his execution at the beginning of the film), prison-like bars and staircases which characters either ascend or descend in a manner that seems almost ritualistic. (In fact, a staircase forms a major part of the film’s climax.) As Joseph Greco notes, this movement up and down staircases suggests ‘an underworld that one must literally enter downward’ (1999: 96). The film features a frequent use of wide-angle lenses that offer an increased depth of field owing to the shorter focal lengths, allowing shots to be staged in depth (such as in the diner at the start of the film, where we see Nick and George in the foreground and the intimidating presence of Max and Al in the background). As Greco notes, in this sequence the ‘overhead lighting [also] makes death-masks of the killer’s faces’ (ibid.). Dickos suggests that Siodmak was the first director associated with film noir ‘to appreciate the complementary value of a sympathetic cinematographer’, in this case Elwood ‘Woody’ Bredell. Siodmak and Bredell had first worked together on Siodmak’s Cornell Woolrich adaptation, Phantom Lady (1944). Bredell made a conscious decision to ‘cut back drastically on lighting, limiting the number of arc lamps for night scenes and foregoing fill light in others’ (Eagan, 2010: 396). The photography throughout the film is excellent: for example, the impeccably staged high-angle long shot which depicts the heist at the Prentiss Hat Factory in a long uninterrupted take. Recurring visual motifs within the film include shots of the Swede lying on beds (constantly recalling his execution at the beginning of the film), prison-like bars and staircases which characters either ascend or descend in a manner that seems almost ritualistic. (In fact, a staircase forms a major part of the film’s climax.) As Joseph Greco notes, this movement up and down staircases suggests ‘an underworld that one must literally enter downward’ (1999: 96). The film features a frequent use of wide-angle lenses that offer an increased depth of field owing to the shorter focal lengths, allowing shots to be staged in depth (such as in the diner at the start of the film, where we see Nick and George in the foreground and the intimidating presence of Max and Al in the background). As Greco notes, in this sequence the ‘overhead lighting [also] makes death-masks of the killer’s faces’ (ibid.).

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The presentation, which takes up just under 30Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, uses the AVC codec. The film seems to be based on the same source as the DVD released by Criterion in the 2000s. The opening shots, featuring the film’s titles, show little step up in terms of detail from Criterion’s DVD; but this is because they’re opticals. When the opening titles end and the killers step into the diner, things improve drastically. The monochrome photography exhibits wonderful tonal range and an impressive level of detail which is evident in, for example, the aforementioned shots within the diner that feature a strong depth of field enabled by the use of lenses with short focal lengths: there is a depth to these shots that is lacking in the impressive-for-the-time Criterion DVD presentation, the counter acting as a leading line carrying the eye of the viewer to the killers seated, then standing, at the end of the counter, intimidating George, Nick and Sam. Contrast is excellent and nicely-balanced, and there is an organic appearance to the film throughout, with a natural level of film grain and no overt evidence of digital tinkering. Apart from some vertical scratches here and there, which are notoriously difficult to remove, the source exhibits little damage. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track. This is clean and clear throughout, showing good range – for example, in the roar of the crowd that accompanies Andreson’s boxing match with Tiger Lewis. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes an isolated music and effects track. This is also presented in lossless mono. The disc includes an isolated music and effects track. This is also presented in lossless mono.

Other extras include: - ‘Frank Krutnik on The Killers’ (54:20). Frank Krutnik provides an introduction to the film: ‘Whatever film noir is, The Killers is definitely it’, he declares. He discusses the film’s origins in Hemingway’s short story. Krutnik talks about the writing of the film and the problems faced by the original writer, Richard Brooks and, later, John Huston – who couldn’t take an official screenplay credit owing to the fact that he was contracted to the US army at the time of the film’s production. Krutnik also talks about Hellinger’s attempts to get Don Siegel to direct the film and Robert Siodmak’s approach to the material. Krutnik then goes on to provide a commentary over four sequences from the film: the opening sequence; the sequence in which Reardon, Lubinsky and Lilly reflect on Andreson’s first meeting with Kitty Collins; the sequence depicting the heist at the Prentiss Hat Factory; and the Green Cat Club sequence. - ‘Heroic Fatalism’ (31:51). This video essay compares Siodmak, Tarkovsky and Siegel’s versions of ‘The Killers’ with the original story. It’s a well-presented, very slickly-edited feature, nicely illustrated with plentiful clips from the various adaptations under discussion. - Radio Killers. These are three radio adaptations of ‘The Killers’, including: -- ‘The Jack Benny Program’ (1946) (10:09). This adaptation, broadcast in the year of the film’s release, offers a parody of the story. -- ‘Screen Director’s Playhouse’ (1949) (29:57). This 1949 adaptation features Burt Lancaster, Shelley Winters and Robert Siodmak. -- ‘Two for the Road’ (1958) (29:10). Here, in a 1958 episode of the series Suspense!, McGraw and Conrad are brought together for another story. - a stills and posters gallery (0:43) - a series of trailers for The Killers (1:47), and for the other Mark Hellinger-produced films noir Brute Force (2:15) and The Naked City (1:52), and a final trailer for Jules Dassin’s Rififi (2:45). All of these films are available on Blu-ray from Arrow. (Please see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Naked City here.) Also included is a handsome booklet containing vintage interviews with Siodmak, Hellinger and Bredell with a new essay by Sergio Angelini. It’s one of Arrow’s characteristically slick booklets, illustrated throughout with stills from the film.

Packaging

The film is packaged in a clear Amaray case, with double-sided artwork: one side features a new design, whereas the reverse side features a version of one of the film's original poster designs.

Overall

Tom Conley has insightfully observed that the ‘innovation in Siodmak’s film lay in the way Hemingway’s piece of spare but highminded “literature” becomes an expressionistic movie trailer both initiating and dissolving into a more pervasive cinematic convention’ (op cit.: 196). The film is an iconic picture within American film noir and sparkles with some fabulous dialogue (in what is arguably the film’s most telling exchange, Colfax tells Reardon, ‘I tell you something, Reardon: if there’s one thing in this world I hate, it’s a double-crossing dame’). Whilst Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross (1949), which also starred Burt Lancaster, is arguably the director’s best film noir, The Killers is nevertheless a superb film. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray disc is very impressive and is also accompanied by some very good contextual material. Criterion’s DVD release included a reading of Hemingway’s story by the actor Stacy Keach and Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1956 short film adaptation of the story – both of which make that DVD release worth hanging on to. But this new Blu-ray easily improves upon the already impressive Criterion DVD, and fans of film noir should find Arrow’s new Blu-ray to be an essential part of their collection. Tom Conley has insightfully observed that the ‘innovation in Siodmak’s film lay in the way Hemingway’s piece of spare but highminded “literature” becomes an expressionistic movie trailer both initiating and dissolving into a more pervasive cinematic convention’ (op cit.: 196). The film is an iconic picture within American film noir and sparkles with some fabulous dialogue (in what is arguably the film’s most telling exchange, Colfax tells Reardon, ‘I tell you something, Reardon: if there’s one thing in this world I hate, it’s a double-crossing dame’). Whilst Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross (1949), which also starred Burt Lancaster, is arguably the director’s best film noir, The Killers is nevertheless a superb film. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray disc is very impressive and is also accompanied by some very good contextual material. Criterion’s DVD release included a reading of Hemingway’s story by the actor Stacy Keach and Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1956 short film adaptation of the story – both of which make that DVD release worth hanging on to. But this new Blu-ray easily improves upon the already impressive Criterion DVD, and fans of film noir should find Arrow’s new Blu-ray to be an essential part of their collection.

References: Conley, Tom, 2000: ‘Noir in the Red and the Nineties in the Black’. In: Dixon, Wheeler Winston, 2000: Film Genre 2000: New Critical Essays. Sate University of New York: 193-210 Dickos, Andrew, 2002: Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film. University Press of Kentucky Eagan, Daniel, 2010: America’s Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum International Publishing Greco, Joseph, 1999: The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood, 1941-1951. Dissertation.com Hirsch, Foster, 1981: The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir. Cambridge: Da Capo Press Letort, Delphine, : ‘The Writing of a Film Noir: Ernest Hemingway and The Killers’. In: Wells-Lassagne, Shannon & Hudelet, Ariane (eds), 2013: Screening Text: Critical Perspectives on Film Adaptation. North Carolina, US: McFarland & Company, Inc.: 53-66 Phillips, Gene D, 2012: Out of the Shadows: Expanding the Canon of Classic Film Noir. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Spicer, Andrew, 2014: ‘Producing Noir: Wald, Scott, Hellinger’. In: Miklitsch, Robert (ed), 2014: Kiss the Blood Off My Hands: On Classic Film Noir. University of Illinois Press: 130-52

|

|||||

|