|

|

God's Pocket (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th December 2014). |

|

The Film

God’s Pocket (John Slattery, 2014) God’s Pocket (John Slattery, 2014)

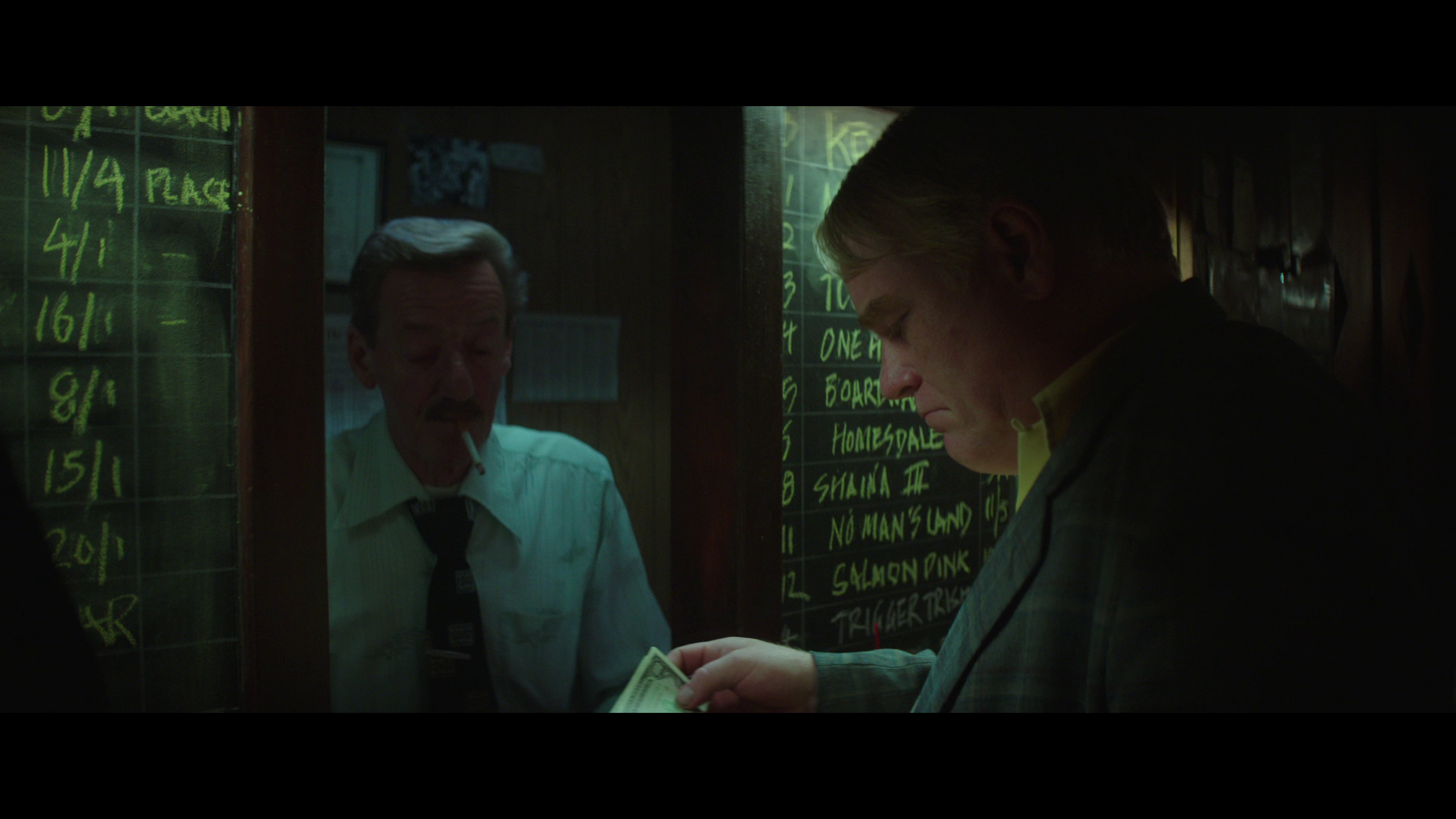

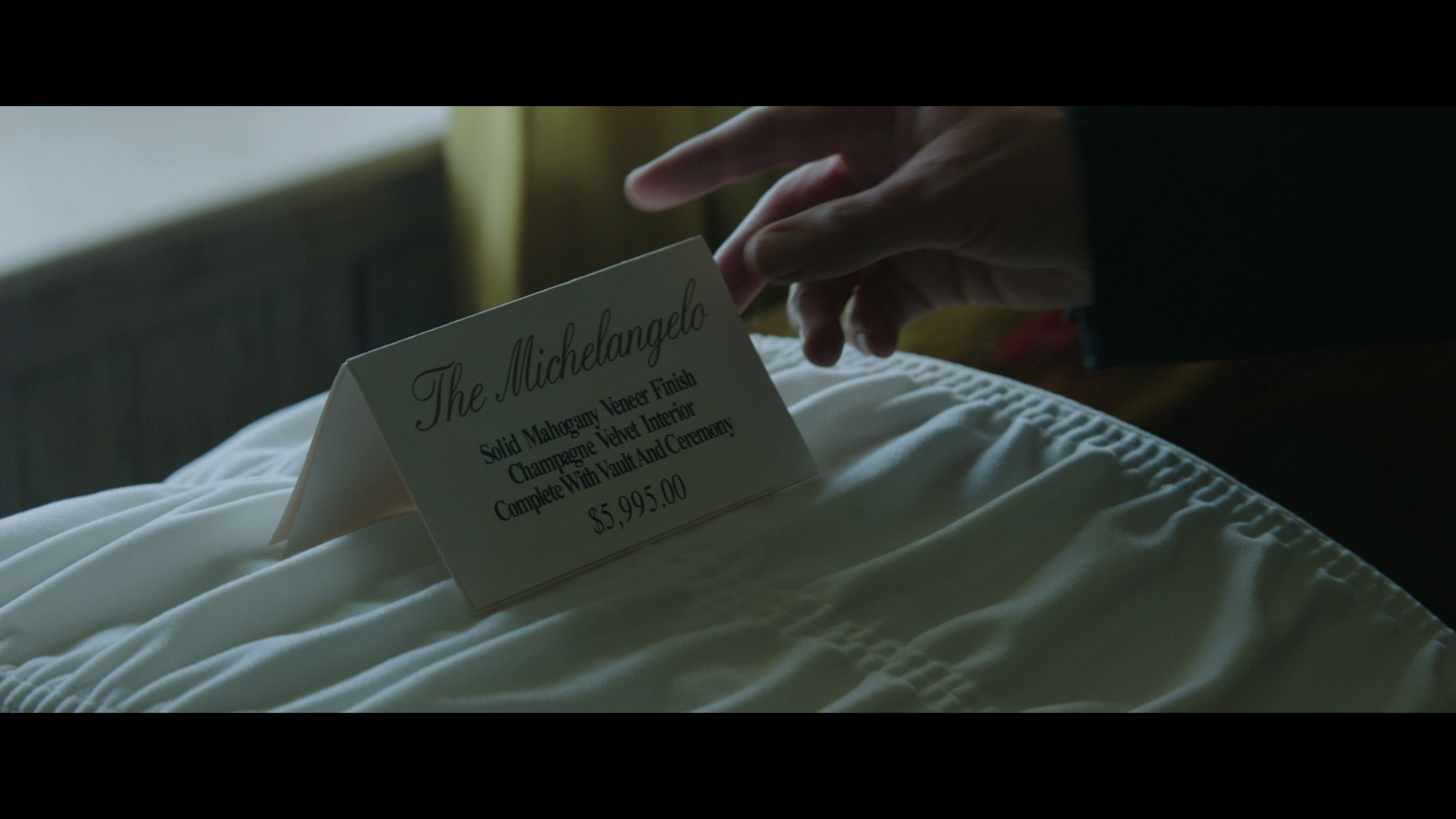

The big screen directorial debut of actor John Slattery, who of recent years has been most famous for his role as Roger Sterling in the acclaimed television series Mad Men (AMC, 2007-15), God’s Pocket is an adaptation of another debut, that of American novelist Pete Dexter. The film follows previous big screen adaptations of Dexter’s novels: Stephen Gyllenhaal’s 1991 adaptation of Paris Trout; Walter Hill’s 1995 adaptation of Dexter’s novel Deadwood, which in its film iteration was given the title Wild Bill; and the recent adaptation of The Paperboy (2012), directed by Lee Daniels. (Dexter also wrote a number of screenplays in the 1990s and early 2000s, including the scripts for Lili Fini Zanuck’s Rush, 1991, itself an adaptation of David Ellsworth’s controversial 1985 non-fiction book Smith County Justice; Lee Tamahori’s noir pastiche Mulholland Falls, 1996; Nora Ephron’s oddball John Travolta-as-angel picture Michael, 1996; and Alec Baldwin’s 2003 reimagining of The Devil and Daniel Webster, titled Shortcut to Happiness.) Gyllenhaal’s Paris Trout, which stars Dennis Hopper as a bigoted shopkeeper/loanshark who commits an act of racially-motivated murder, explores the landscape of bigotry, hate crimes and tensions within a small community; in doing so, its themes overlap somewhat with those of God’s Pocket. And where Paris Trout is anchored by a characteristically outrageous performance by Dennis Hopper (which is offset by the work of his co-stars Barbara Hershey and Ed Harris), God’s Pocket is similarly anchored by an equally characteristically strong performance from Philip Seymour Hoffman that would sadly turn out to be one of the actor’s final screen roles. First published in 1983, Dexter’s source novel is largely autobiographical: it was written after Dexter, who at the time was working as a reporter for the Philadelphia Daily News, suffered a severe beating at the hands of a group of men from Philadelphia’s Devil’s Pocket, after they took offence at one of his articles. The beating resulted in Dexter’s back and hip being broken; the incident inspired Dexter to pursue a new career as a novelist. The novel, and this film, focus on the small community of God’s Pocket (a thinly-veiled reference to Philadelphia’s Devil’s Pocket). The film opens with the funeral of Leon Hubbard (Caleb Landry Jones), the son of Jeanie Scarpato (Christina Hendricks) and the step-son of Jeanie’s husband Mickey Scarpato (Hoffman), before looking back to the circumstances surrounding Leon’s death. Despite his mother’s celebration of his life, Leon, it seems, was a spiteful blowhard and a bigot who, on the construction site on which he worked, taunted his colleagues with stories of his cruelty to animals and abused his only African American colleague, a forklift truck operator (‘I wanna know what a white man’s doin’ walklin’, while this nigger rides around all day’, Leon declares cruelly). When this colleague snaps after Leon threatens him with physical violence – hitting Leon on the head with a piece of pipe, killing Leon accidentally – the site foreman lies to the police and claims Leon’s death to be the result of an accident. The other workmen, alienated by Leon’s cruel behaviour, support the foreman’s version of events.  Meanwhile, Mickey is involved in the theft of a refrigerated meat truck, along with Mickey’s friend Arthur ‘Bird’ Capezio (John Turturro) and Sal Cappi (Domenick Lombardozzi). The theft has been organised by Bird as a means of paying off his debts. At the same time, we are introduced to local journalist Richard Shellburn (Richard Jenkins); a celebrity within the community, Shellburn is responsible for a regular column in the local newspaper, but he’s tired of his work and his commitment to it. When news of Leon’s death breaks, Shellburn is asked by his editor to investigate the incident. Mickey, on the other hand, finds himself struggling to pull together the finances for Leon’s funeral: unlike Jeanie, Mickey seems to be cognisant of the fact that Leon was little more than a despicable shit, but he is under unstated pressure from Jeanie to ensure that Leon has a good send-off. The patrons of the local bar, the Hollywood, pull together a collection for the funeral, but Mickey blows it at the races; and as a result, the funeral director, ‘Smiling’ Jack Moran (Eddie Marsan), returns Leon’s body back to Mickey, who hides it in the refrigerated meat truck as he drives the truck around God’s Pocket in an attempt to hawk the stolen meat. When the truck is taken without Mickey’s consent and involved in a traffic accident, Mickey finds himself struggling to explain the reappearance of Leon’s body. Meanwhile, Richard finds himself involved in an affair with Jeanie and, after Leon’s funeral, writing an article about God’s Pocket which is misinterpreted by the locals and results in Richard being subjected to a severe beating by the patrons of the Hollywood, which Mickey is powerless to stop. Meanwhile, Mickey is involved in the theft of a refrigerated meat truck, along with Mickey’s friend Arthur ‘Bird’ Capezio (John Turturro) and Sal Cappi (Domenick Lombardozzi). The theft has been organised by Bird as a means of paying off his debts. At the same time, we are introduced to local journalist Richard Shellburn (Richard Jenkins); a celebrity within the community, Shellburn is responsible for a regular column in the local newspaper, but he’s tired of his work and his commitment to it. When news of Leon’s death breaks, Shellburn is asked by his editor to investigate the incident. Mickey, on the other hand, finds himself struggling to pull together the finances for Leon’s funeral: unlike Jeanie, Mickey seems to be cognisant of the fact that Leon was little more than a despicable shit, but he is under unstated pressure from Jeanie to ensure that Leon has a good send-off. The patrons of the local bar, the Hollywood, pull together a collection for the funeral, but Mickey blows it at the races; and as a result, the funeral director, ‘Smiling’ Jack Moran (Eddie Marsan), returns Leon’s body back to Mickey, who hides it in the refrigerated meat truck as he drives the truck around God’s Pocket in an attempt to hawk the stolen meat. When the truck is taken without Mickey’s consent and involved in a traffic accident, Mickey finds himself struggling to explain the reappearance of Leon’s body. Meanwhile, Richard finds himself involved in an affair with Jeanie and, after Leon’s funeral, writing an article about God’s Pocket which is misinterpreted by the locals and results in Richard being subjected to a severe beating by the patrons of the Hollywood, which Mickey is powerless to stop.

Writing about Pete Dexter’s source novel, Carlo Rotella describes the community of God’s Pocket as a ‘rowhoused white-ethnic enclave […] fiercely struggling against the grain of urban change’, which has its roots in the ‘immigrant-ethnic industrial village’ depicted within Jack Dunphy’s 1946 novel John Fury – a novel depicting the lives of a community of Irish Americans living within South Philadelphia during the first half of the 20th Century (Rotella, 1998: 169). Rotella argues that Dexter’s God’s Pocket was part of a wave of ‘neighbourhood novels’ published in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s that, taking their cues from the narrative devices within Dunphy’s John Fury and William Gardner Smith’s South Street (1954), examined the ‘tension between the metropolitan and the local’ through the lens of ‘family narratives, expressive landscapes, runaway scenes, and the presence of writer-characters struggling to make sense of the neighborhood in crisis and its relation to the metropolis’ (ibid.). (Parallels could be drawn between these ‘neighbourhood novels’ and ‘hood films’ such as Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, 1989, the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society, 1993, and John Singleton’s Boyz ‘n’ the Hood, 1991.) These novels are also, in one way or another, often about ‘the making or unmaking of urban intellectuals’ (ibid.: 121). Richard Shellburn, a writer-character who offers an outsider’s perspective on God’s Pocket, is one such ‘urban intellectual’ – initially hailed as a hero by the community (‘Mr Shellburn, you’re the only one who knows what it’s like down here in the pocket. God bless you’, he is told by a patron on his first visit to the Hollywood) but, at the end of the narrative, singled out as a villain by the same community (‘What the fuck you writin’ about us in the paper for? [….] You ain’t from around here, and you’re makin’ us look like assholes’, he is told on his final visit to the Hollywood, before he is beaten to death in the street). Writing about Pete Dexter’s source novel, Carlo Rotella describes the community of God’s Pocket as a ‘rowhoused white-ethnic enclave […] fiercely struggling against the grain of urban change’, which has its roots in the ‘immigrant-ethnic industrial village’ depicted within Jack Dunphy’s 1946 novel John Fury – a novel depicting the lives of a community of Irish Americans living within South Philadelphia during the first half of the 20th Century (Rotella, 1998: 169). Rotella argues that Dexter’s God’s Pocket was part of a wave of ‘neighbourhood novels’ published in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s that, taking their cues from the narrative devices within Dunphy’s John Fury and William Gardner Smith’s South Street (1954), examined the ‘tension between the metropolitan and the local’ through the lens of ‘family narratives, expressive landscapes, runaway scenes, and the presence of writer-characters struggling to make sense of the neighborhood in crisis and its relation to the metropolis’ (ibid.). (Parallels could be drawn between these ‘neighbourhood novels’ and ‘hood films’ such as Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, 1989, the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society, 1993, and John Singleton’s Boyz ‘n’ the Hood, 1991.) These novels are also, in one way or another, often about ‘the making or unmaking of urban intellectuals’ (ibid.: 121). Richard Shellburn, a writer-character who offers an outsider’s perspective on God’s Pocket, is one such ‘urban intellectual’ – initially hailed as a hero by the community (‘Mr Shellburn, you’re the only one who knows what it’s like down here in the pocket. God bless you’, he is told by a patron on his first visit to the Hollywood) but, at the end of the narrative, singled out as a villain by the same community (‘What the fuck you writin’ about us in the paper for? [….] You ain’t from around here, and you’re makin’ us look like assholes’, he is told on his final visit to the Hollywood, before he is beaten to death in the street).

Dexter’s God’s Pocket, along with David Bradley’s somewhat similar novel South Street (1975), was written ‘in the aftermath of the urban crisis that was brewing midcentury’ (Rotella, op cit.: 125). Like many of the ‘neighbourhood’ novels of the same era, God’s Pocket foregrounds violence – often centred on issues of racial difference or bigotry. Dexter’s book depicts the citizens within God’s Pocket, which represents the ‘anachronistic survival of the white-ethnic urban village’, reacting ‘with violence and bewilderment’ to the ‘outside’ world, represented firstly through Leon’s cruel treatment of his African American colleague (identified by Leon as an ethnic ‘other’) and, ultimately, by the fatal beating that is administered to Richard when the article he writes for the newspaper is misconstrued as an attack upon the community of God’s Pocket by the patrons of the Hollywood bar (ibid.). The ‘neighbourhood novels’ foreground the extent to which family is essential to concepts of community, functioning as ‘the building blocks of neighborhoods’ (Rotella, op cit.: 126). In the majority of neighbourhood novels, including God’s Pocket, ‘marriages are collapsing, barren, sexless, cursed with bad feeling or ill health or poor luck’ (ibid.). Families are ridden with ‘bad offspring’ who ‘fritter away their inheritance’ and/or, in the case of sons, refuse to work; or in the case of daughters, alienate their families through their desire for social mobility (ibid.). Leon is beatified by his mother Jeanie and by some of those within the local community, though this is undercut by the audience, who witness his cruelty and his spitefulness – both to animals and his fellow humans. Mickey seems cognisant of Leon’s failings, though trapped in a humourless, unfulfilling marriage with Jeanie he is unable to express this. As the narrative develops, Richard becomes aware of the aspects of Leon’s character that Jeanie and the community have sought to forget, which leads to the comments made in his final column. In that column, Richard observes that ‘Leon Hubbard was like the other working people of God’s Pocket: dirty-faced, uneducated […] They work, marry and have children who inhabit God’s Pocket, often in the homes of their mothers and fathers. They drink at the Hollywood or the uptown bar […] and they argue there about things they don’t understand: politics, race, religion. And in the end, they die like everyone else, leaving their families, and their houses, and their legends [….] If we stop listening to Leon Hubbard’s story and all the stories like it, eventually the neighbourhoods would stop listening to ours’.  In many ways, Jeanie is the pivot of the narrative: the film’s chief male characters – Mickey, Richard and Leon – revolve around her. However, she is a passive character, as shown in the sex scene between her and Mickey that takes place early in the film. This is juxtaposed with a scene depicting Leon in his bedroom, where (in a pastiche of the famous ‘You talking to me?’ scene from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, 1976), he practices being tough in front of a mirror: whilst dressing, he pulls out a knife and declares, ‘What the fuck you looking at?’ Jeanie is also (willfully?) naïve. She eulogises to Richard about her dead son Leon, declaring ‘He always wanted a dog or a cat or something’, but at the start of the film we see Leon boasting about his cruel treatment of a kitten. The source of Leon’s spiteful behaviour is never explained; but cruelty seems to be endemic within the community of God’s Pocket, as Richard’s beating at the end of the film suggests. Mickey is a petty criminal, a low-ranking ‘friend of mine’ who exists on the fringes of organised crime. However, the threat represented by organised crime within the community is undercut in a number of sequences. In one of these sequences, the foreman of the site on which Leon died is questioned, and threatened, by some of Sal’s men. However, the foreman soon turns the tables on his attackers, plucking out the eye of one of them and thrashing the other. In another sequence, Sal and one of his men pay a visit to Bird, to collect a debt he owes to Sal. However, both gangsters are bested by Bird’s friend Sophie (Joyce Van Patten), the elderly owner of a flower shop, who shoots them both dead. In many ways, Jeanie is the pivot of the narrative: the film’s chief male characters – Mickey, Richard and Leon – revolve around her. However, she is a passive character, as shown in the sex scene between her and Mickey that takes place early in the film. This is juxtaposed with a scene depicting Leon in his bedroom, where (in a pastiche of the famous ‘You talking to me?’ scene from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, 1976), he practices being tough in front of a mirror: whilst dressing, he pulls out a knife and declares, ‘What the fuck you looking at?’ Jeanie is also (willfully?) naïve. She eulogises to Richard about her dead son Leon, declaring ‘He always wanted a dog or a cat or something’, but at the start of the film we see Leon boasting about his cruel treatment of a kitten. The source of Leon’s spiteful behaviour is never explained; but cruelty seems to be endemic within the community of God’s Pocket, as Richard’s beating at the end of the film suggests. Mickey is a petty criminal, a low-ranking ‘friend of mine’ who exists on the fringes of organised crime. However, the threat represented by organised crime within the community is undercut in a number of sequences. In one of these sequences, the foreman of the site on which Leon died is questioned, and threatened, by some of Sal’s men. However, the foreman soon turns the tables on his attackers, plucking out the eye of one of them and thrashing the other. In another sequence, Sal and one of his men pay a visit to Bird, to collect a debt he owes to Sal. However, both gangsters are bested by Bird’s friend Sophie (Joyce Van Patten), the elderly owner of a flower shop, who shoots them both dead.

The film runs for 88:37 mins.

Video

Shot digitally, the film is presented in an aspect ratio of 2.40:1, in 1080p (using the AVC codec). (The presentation takes up approximately 20Gb of a single-layered disc.) Contrast is good, but in its low-light sequences, especially given its retro aesthetic (the narrative seems to take place at some point in the 1980s), the film cries out for the texture of celluloid film. (It’s arguably the same issue that Michael Mann’s Public Enemies faced: the tension between the digital ‘look’ of the film and its period setting.) Also, given the intimate nature of the narrative, a narrower screen ratio (eg, 1.85:1) would perhaps have been more appropriate – as compared with the ‘epic’ connotations of the widescreen image. Nevertheless, the film’s presentation on this Blu-ray is very good: colour reproduction is solid, and there’s a strong level of detail present.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track, which is clear throughout and free of issues.

Extras

The disc includes a trailer (2:12) and a small collection of deleted scenes (2:47).

Overall

John Slattery’s adaptation of God’s Pocket works very nicely in depicting the frustrated, insular lives of the citizens of that community, and it is aided by some strong performances from Hoffman and Jenkins, in particular. The film’s juxtaposition of Mickey and Richard’s lives, and the ways in which these two characters come together owing to the death of Leon and their shared involvement with Jeanie, highlights the insular, almost incestuous, nature of the community depicted within the film – something which is foregrounded in the two articles by Richard which, narrated by Richard Jenkins in the opening and closing sequences, examine the characteristics of God’s Pocket. ‘The working men of God’s Pocket are simple men’, the Richard’s narration (over the funeral of Leon, which opens the film) declares, ‘They work, they follow routines, they marry and have children, who rarely leave the Pocket. Everyone has stolen something from somebody else, or when they were kids they set someone’s house on fire. Or they ran away when they should have stayed and fought. They know who cheats at cards and who slaps their kids around. And no matter what anybody does, they’re still here; and whatever they are, is what they are. The only thing they can’t forgive is not being from God’s Pocket’. It’s this final declaration that forms much of the film’s focus: Leon’s attacks on those he perceives as ‘other’ to him; and the final assault that leads to the death of Richard, which Mickey is powerless to stop (‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’, Mickey asks the Richard’s attackers, to which the bartender of the Hollywood tells Mickey, ‘You ain’t from around here, either’). John Slattery’s adaptation of God’s Pocket works very nicely in depicting the frustrated, insular lives of the citizens of that community, and it is aided by some strong performances from Hoffman and Jenkins, in particular. The film’s juxtaposition of Mickey and Richard’s lives, and the ways in which these two characters come together owing to the death of Leon and their shared involvement with Jeanie, highlights the insular, almost incestuous, nature of the community depicted within the film – something which is foregrounded in the two articles by Richard which, narrated by Richard Jenkins in the opening and closing sequences, examine the characteristics of God’s Pocket. ‘The working men of God’s Pocket are simple men’, the Richard’s narration (over the funeral of Leon, which opens the film) declares, ‘They work, they follow routines, they marry and have children, who rarely leave the Pocket. Everyone has stolen something from somebody else, or when they were kids they set someone’s house on fire. Or they ran away when they should have stayed and fought. They know who cheats at cards and who slaps their kids around. And no matter what anybody does, they’re still here; and whatever they are, is what they are. The only thing they can’t forgive is not being from God’s Pocket’. It’s this final declaration that forms much of the film’s focus: Leon’s attacks on those he perceives as ‘other’ to him; and the final assault that leads to the death of Richard, which Mickey is powerless to stop (‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’, Mickey asks the Richard’s attackers, to which the bartender of the Hollywood tells Mickey, ‘You ain’t from around here, either’).

The presentation of the film on this disc is very good, though it would have been interesting to see some more in-depth contextual material – for example, interviews with Slattery or his actors, or with Pete Dexter. In many ways, the film feels like a throwback to the independent crime films of the 1990s – dialogue-based crime pictures such as Palookaville (Alan Taylor, 1995) that told stories about human failures and frustrations – which is a good thing, especially in the context of today’s emphasis on the cinema of spectacle. Ultimately, God’s Pocket is a rewarding film, and this is a commendable Blu-ray release. References: Rotella, Carlo, 1998: October Cities: The Redevelopment of Urban Literature. University of California Press

|

|||||

|