|

|

Man Who Knew Too Much (The)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th January 2015). |

|

The Film

The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934) The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934)

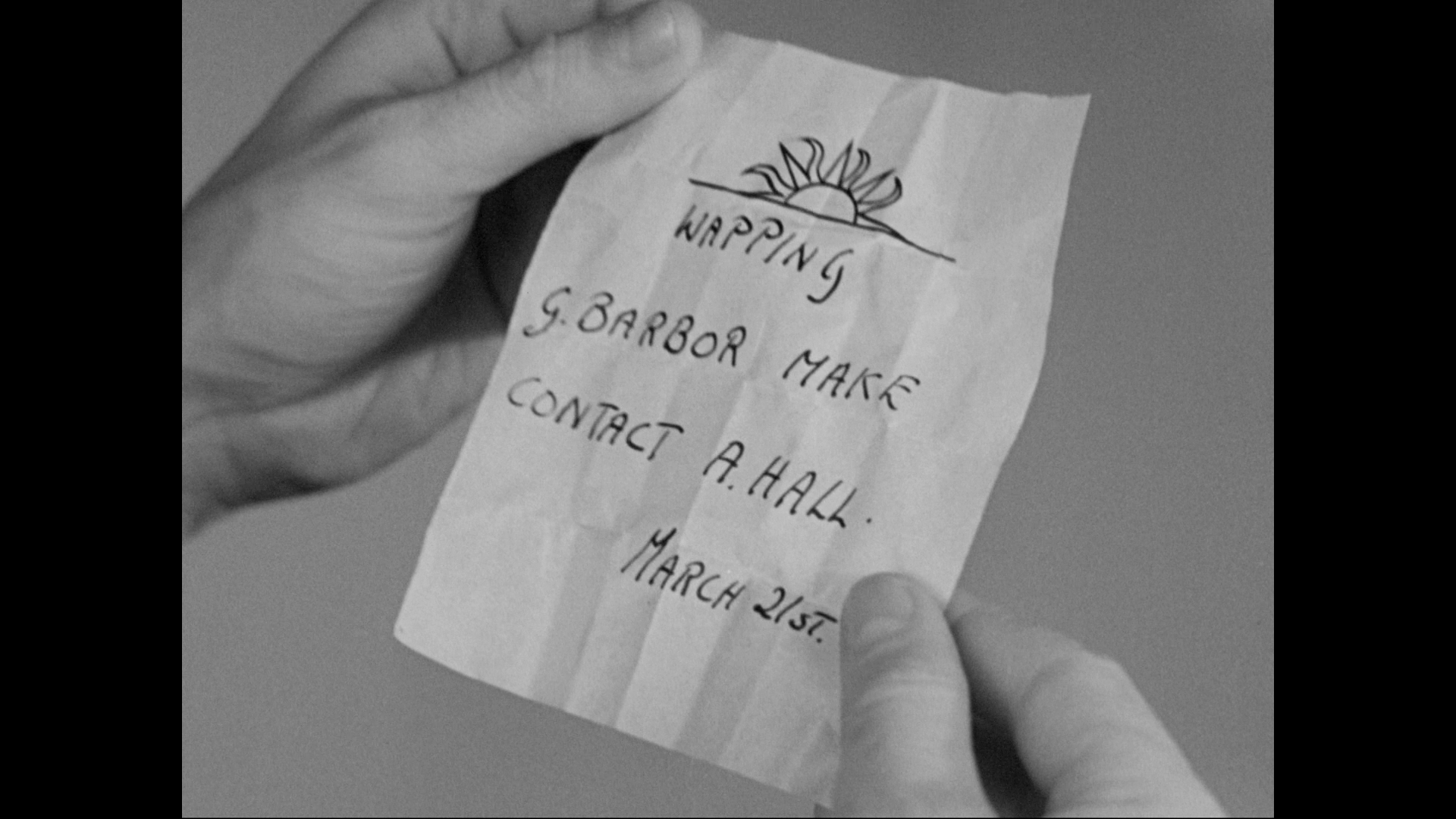

In his introduction to the film on this disc (carried over from Network’s 2008 DVD release), Charles Barr argues that the 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much, which Hitchcock would remake as a glossy Hollywood thriller a little over twenty years later, was a ‘homecoming’ of sorts for Hitchcock: a return to his collaboration with the producer Michael Balcon, who had given Hitchcock his first opportunity to direct a film. Coming immediately after the critical failure of Hitchcock’s first musical, Waltzes from Vienna (1934), The Man Who Knew Too Much was also the first of six consecutive thrillers that would in many ways sketch the approach that would be evidenced throughout Hitchcock’s later Hollywood films, a template that Barr argues was to some extent provided by the work of screenwriter Charles Bennett, who had previously written the play on which Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929) was based, and who would pen Hitchcock’s subsequent four films. Beginning in St Moritz, the film follows the Lawrences, Bob (Leslie Banks) and his wife Jill (Edna Best), a wizard clay pigeon shooter. The Lawrences, including their daughter Betty (Nova Pilbeam), are on holiday with their friend Louis (Pierre Fresnay), a champion skier. However, Louis is shot, killed by an unknown assassin. Before he dies, he tells Jill to inform Bob that he must take ‘the brush in my room’ to the British consul and ‘don’t breathe a word to anyone’. Acting on Louis’ words, Bob investigates Louis’ room and, taking a look at his friend’s shaving brush, discovers a mysterious note hidden inside. Whilst Bob and Jill struggle to communicate with the local police who are investigating the shooting of Louis, their daughter Betty is abducted and a cryptic message left at the scene, ‘Say nothing of what you found or you will never see your child again’. Returning to England, Bob and Jill struggle to cover the absence of Betty, telling friends that she is staying with an aunt in Paris, on a street with a ‘rather complicated French name, rather difficult for an English person to pronounce’. Bob is approached by Gibson (George Curzon) from the Foreign Office, who tells Bob that ‘Your friend Luis was one of our people. Special Service’. Gibson surmises that Betty has been abducted in order to silence Bob and Jill. Gibson tells the Lawrences that there is a plot to assassinate a foreign diplomat, Ropa, and that Louis’ information could help to prevent the assassination from being successful. Aware that they are unable to seek Gibson’s help, or Betty’s kidnappers will kill her as they have threatened to do, Jill and Bob decide to ‘act ourselves’ to recover Betty. In doing so, they enlist the help of Clive (Hugh Wakefield).  Bob and Clive follow a clue to a backstreet dental surgery, where they encounter Abbott (Peter Lorre), who they realise is one of Betty’s kidnappers. They follow Abbott to a church. However, their true identities are soon rumbled, and Abbott has them held at gunpoint, telling Bob, ‘You should learn to control your fatherly feelings’. Clive manages to escape but Bob is held captive. However, when Clive seeks help from the police, he finds the tables turned when Abbott tells a policeman that Clive was drunk and disorderly in the church, and Clive is arrested for ‘Disorderly behaviour in a place of edifice’. Bob and Clive follow a clue to a backstreet dental surgery, where they encounter Abbott (Peter Lorre), who they realise is one of Betty’s kidnappers. They follow Abbott to a church. However, their true identities are soon rumbled, and Abbott has them held at gunpoint, telling Bob, ‘You should learn to control your fatherly feelings’. Clive manages to escape but Bob is held captive. However, when Clive seeks help from the police, he finds the tables turned when Abbott tells a policeman that Clive was drunk and disorderly in the church, and Clive is arrested for ‘Disorderly behaviour in a place of edifice’.

Before he is arrested, however, Clive has time to telephone Jill. With the information presented to her, Jill surmises that the attempt to assassinate Ropa will take place at the Albert Hall during a concert that evening. Jill visits the Albert Hall in an attempt to foil Abbott’s plan. The film’s narrative isn’t particularly complicated, but as Peter John Dyer noted in 1961, the picture is ‘outright melodrama, deficient in structure and flawed in its logic. But its very recklessness gave it an excitement hitherto unknown in the British cinema’ (quoted in Yacowar, 2010: 136). Hitchcock himself expressed his preference for this version of The Man Who Knew Too Much over his own Hollywood remake, asserting that ‘it [the 1934 film] was more spontaneous—it had less logic. Logic is dull: you lose the bizarre and the spontaneous’ (quoted in ibid.).  As Maurice Yacowar notes, the overriding tension within this film and Hitchcock’s other British thrillers arises from the conflict between ‘private interest and public duty’ (ibid.). Like a number of other Hitchcock protagonists, the Lawrences find the perils of the outside world – the public sphere – intruding on their safe, protected family life – the private sphere. When, upon returning to England, Bob is told by Gibson of the plot against Ropa’s life, Bob protests, ‘It’s her [Betty’s] life against this fellow Ropa’s. Why should we care if some foreign statesman we’ve never even heard of were assassinated?’ To this, Gibson responds: ‘Tell me: in June 1914, had you ever heard of a place called Sarajevo? Of course you hadn’t. I doubt if you’d ever heard of the Archduke Ferdinand. But in a month’s time, because a man you’d never heard of killed another man in a place you’d never heard of, this country was at war’. At the end of the sequence, Gibson bids the Lawrences farewell, advising them, ‘Well, if there is any trouble, I hope you remember you’re to blame. Not a nice thing to have on your conscience’. As Maurice Yacowar notes, the overriding tension within this film and Hitchcock’s other British thrillers arises from the conflict between ‘private interest and public duty’ (ibid.). Like a number of other Hitchcock protagonists, the Lawrences find the perils of the outside world – the public sphere – intruding on their safe, protected family life – the private sphere. When, upon returning to England, Bob is told by Gibson of the plot against Ropa’s life, Bob protests, ‘It’s her [Betty’s] life against this fellow Ropa’s. Why should we care if some foreign statesman we’ve never even heard of were assassinated?’ To this, Gibson responds: ‘Tell me: in June 1914, had you ever heard of a place called Sarajevo? Of course you hadn’t. I doubt if you’d ever heard of the Archduke Ferdinand. But in a month’s time, because a man you’d never heard of killed another man in a place you’d never heard of, this country was at war’. At the end of the sequence, Gibson bids the Lawrences farewell, advising them, ‘Well, if there is any trouble, I hope you remember you’re to blame. Not a nice thing to have on your conscience’.

Bob and Jill’s marriage is as much the focus of the film as the thriller plot that is at the centre of the narrative. Jill, who early in the film is introduced as an expert clay pigeon shooter, inhabits a role that is far from the passive position usually occupied by women, especially wives or lovers of a male protagonist, in thriller plots. Upon returning to England, after deciding that they cannot turn to Gibson and the Foreign Office for help without endangering the life of Betty, Bob and Jill work separately to foil the assassination plot that has been put together by the group of agitators led by Abbott; Hitchcock crosscuts Bob and Jill’s investigations, with Bob (unknowingly) passing the baton to Jill when he is captured by Abbott’s group. In the Hollywood remake of 1956, the character of Jill, played in that version by Doris Day, is made to be much more passive: the remake, like Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), features James Stewart in an embodiment of ‘troubled’ masculinity; part of a couple whose relationship is revived, in response to the ‘joint quest’ presented by the narrative, which serves in the denouement to ‘realign […] gendered epistemologies’ (Allen, 2007: 90).  The film’s climax, in which the police lay siege to a house containing Abbott’s band of terrorists, was inspired by the Sidney Street siege which took place in 1911, in which a group of anarchists allegedly led by Peter Piatkow (‘Peter the Painter’) were surrounded by two hundred police officers and a detachment of Scots Guards after several police officers where killed whilst investigating a botched burglary at a Houndsditch jeweller’s shop. In reinterpreting this event within the context of the film’s narrative, Hitchcock includes some shockingly abrupt violence (two police officers, taking a position in a house facing that in which Abbott’s gang are hiding, discuss their families before both being shot through a window) and also incorporates some delicious black humour. During the final shootout, having cornered the agitators, the police barricade the street. A postman stumbles up to the police barricade and asks ‘What’s up?’. ‘We’ve got orders to clear these streets’, a policeman tells him. ‘I’ve got orders to clear my box’, the postman retorts before going about his business, ignoring the barricade. The film’s climax, in which the police lay siege to a house containing Abbott’s band of terrorists, was inspired by the Sidney Street siege which took place in 1911, in which a group of anarchists allegedly led by Peter Piatkow (‘Peter the Painter’) were surrounded by two hundred police officers and a detachment of Scots Guards after several police officers where killed whilst investigating a botched burglary at a Houndsditch jeweller’s shop. In reinterpreting this event within the context of the film’s narrative, Hitchcock includes some shockingly abrupt violence (two police officers, taking a position in a house facing that in which Abbott’s gang are hiding, discuss their families before both being shot through a window) and also incorporates some delicious black humour. During the final shootout, having cornered the agitators, the police barricade the street. A postman stumbles up to the police barricade and asks ‘What’s up?’. ‘We’ve got orders to clear these streets’, a policeman tells him. ‘I’ve got orders to clear my box’, the postman retorts before going about his business, ignoring the barricade.

The idea for the film came to Hitchcock in 1927, and Hitchcock originally conceived it as a vehicle for the popular character of Bulldog Drummond (Glancy, 2011: 79). It has been asserted that the version of The Man Who Knew Too Much that made it to the screen in 1934 was more closely informed quite heavily by the work of John Buchan, whose novel The 39 Steps Hitchcock would adapt for the big screen in 1935. Mark Glancy has gone as far as saying that ‘Buchan’s signature is apparent throughout’ The Man Who Knew Too Much, and that ‘[i]n terms of plot devices, story elements, and characterization, the film owes a significant debt’ to Buchan’s Richard Hannay novels (ibid.: 78). In particular, Buchan’s novel The Three Hostages has been cited as a direct influence over the direction taken by the script for The Man Who Knew Too Much (Glancy, 2003: 22). However, it could also be argued that The Man Who Knew Too Much’s depiction of an anarchist plot on English soil has as much in common with Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel The Secret Agent, which Hitchcock filmed as Sabotage in 1936. (Hitchcock’s Sabotage was reputedly inspired more by Conrad’s own adaptation of The Secret Agent as a stage play than by the novel; in the role of Ramon, on of Abbott’s cronies, The Man Who Knew Too Much features one of the actors from that stage version of Conrad’s novel, Frank Vosper, who had played Mr Vladimir in Conrad’s play.) The film is uncut and runs for 75:34 mins.

Video

Taking up just under 15Gb on a single-layered disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome 35mm photography is very nicely-presented here, with a good level of detail. (One aspect of Blu-ray presentations of features shot in the 1920s and 1930s that I’ve come to enjoy is the way in which the HD format’s increased ability to resolve detail and contrast highlights the characteristics of the lenses used during that era.) There is a natural level of grain throughout the film. Taking up just under 15Gb on a single-layered disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome 35mm photography is very nicely-presented here, with a good level of detail. (One aspect of Blu-ray presentations of features shot in the 1920s and 1930s that I’ve come to enjoy is the way in which the HD format’s increased ability to resolve detail and contrast highlights the characteristics of the lenses used during that era.) There is a natural level of grain throughout the film.

The print itself is remarkable clean. A couple of shots seem to have a softness that may or may not be a product of the original photography – or which may suggest damage to the source used for this transfer – and there are a few examples of judder here and there. Additionally, in a few sequences there seem to be one or two very minor examples of ringing artifacts, which may be evidence of some digital sharpening, but on the whole the presentation feels very organic and film-like. For larger screen grabs, please see the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless LPCM 2.0 dual mono track. This is clear throughout. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes an introduction by critic Charles Barr (3:47), which has been carried over from Network’s 2008 DVD release. Also included is ‘Alfred the Great’, the 1972 episode of LWT’s arts programme Aquarius, which features a studio interview with Hitchcock (35:33). The episode, sadly, has been edited for rights reasons, eliminating much of the discussion of Hitchcock’s then-in-production Frenzy that was featured in the original broadcast version. Finally, a stills gallery (1:44) is included.

Overall

The Man Who Knew Too Much remains a sparkling film that, in today’s panics about terrorism and sleeper cells, retains much of its relevance. It was the first of two Hitchcock films which featured Peter Lorre (who also appeared in The Secret Agent), and Lorre’s presence – on his way to starring roles in Hollywood films such as The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1941) – reminds us of the similarities that, during the late-1930s, were often drawn between Hitchcock and Fritz Lang, who only a few years earlier had directed Lorre in the astounding M (1931). Here, Lorre offers an incredibly creepy presence: on the surface filled with good humour, but evidencing through his actions a profound sense of sadism. The Man Who Knew Too Much remains a sparkling film that, in today’s panics about terrorism and sleeper cells, retains much of its relevance. It was the first of two Hitchcock films which featured Peter Lorre (who also appeared in The Secret Agent), and Lorre’s presence – on his way to starring roles in Hollywood films such as The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1941) – reminds us of the similarities that, during the late-1930s, were often drawn between Hitchcock and Fritz Lang, who only a few years earlier had directed Lorre in the astounding M (1931). Here, Lorre offers an incredibly creepy presence: on the surface filled with good humour, but evidencing through his actions a profound sense of sadism.

The film contains some wonderfully tense sequences. For example, in the sequence in which Bob and Clive follow the conspirators to a backstreet dental surgery (replaced, in the remake, by a taxidermists), Bob waits outside whilst Clive investigates. As Bob stands outside the door, he hears Clive scream. Bob readies himself with a gun, but Clive exits to reveal that the dentist has only pulled one of his teeth. Bob then enters the dentist’s office and, whilst the dentist looks into his mouth, Abbott walks through the surgery into a back room. Meanwhile, the dentist realises that Bob is investigating him and tries to use gas to subdue Bob. Bob manages to turn the tables on the dentist and knocks him out instead before masquerading as the dentist, allowing him to overhear Abbott’s conversation with another man which reveals that he is part of the group that abducted Betty. However, throughout the film Hitchcock also displays a consistently dry sense of humour. In the opening sequence, set in Switzerland, Louis asks Jill (who, of course, he knows is married to Bob), ‘What do you think of the average Englishman?’ Jill responds by asserting, ‘Too cold. Except when he drinks too much of course’. Later, in the sequence in which Bob and Clive enter the church which functions as a ‘cover’ for Abbott’s band of agitators, as the gathered flock sing a hymn, Bob and Clive pretend to sing along whilst – in a manner all too familiar to viewers of The Two Ronnies – they quietly converse with one another about the events they have witness. Once Bob and Clive have been rumbled by Abbott’s group and a bizarrely chaotic fight breaks out, with the participants throwing chairs at one another, an elderly woman opts to play the organ to cover the noise. This Blu-ray presentation of this classic Hitchcock film is very pleasing and seems to be a significant upgrade from previously-available DVD versions. The region ‘A’ locked release from Criterion offers a far more ‘meaty’ selection of extras (including an audio commentary by Philip Kemp), but the inclusion of ‘Alfred the Great’ means that Network’s new Blu-ray complements that release very nicely, offering a great alternative for region ‘B’ locked viewers. References: Allen, Richard, 2007: Hitchcock’s Romantic Irony. Columbia University Press Glancy, Mark, 2003: British Film Guides: ‘The 39 Steps’. London: I B Tauris Glancy, Mark, 2011: ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934): Alfred Hitchcock, John Buchan, and the Thrill of the Chase’. In: Palmer, R Barton & Boyd, David (eds), 2011: Hitchcock at the Source: The Auteur as Adaptor. State University of New York Press: 77-88 Yacowar, Maurice, 2010: Hitchcock’s British Films. Wayne State University Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|