|

|

Thief (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th January 2015). |

|

The Film

Thief (Michael Mann, 1981)  Michael Mann’s first theatrical film (although his television film The Jericho Mile received a cinema release in Europe), Thief (1981), originally released in the UK as Violent Streets, offered a crystallisation of many of the themes of Mann’s later work. Although Mann’s earlier television work (for example, his scripts for Starsky & Hutch, 1975-8, and Police Story, 1973-7) evidenced a fascination with the relationships between the police and criminals, Thief established Mann’s focus on the work of professional criminals who are defined by their work and the obsessive members of law enforcement who seek to catch them – which would become a defining characteristic of many of Mann’s subsequent films. Thief also helped to establish Mann’s signature style, and like many of Mann’s subsequent pictures, at the time of its release Thief was criticised as privileging style over substance. Michael Mann’s first theatrical film (although his television film The Jericho Mile received a cinema release in Europe), Thief (1981), originally released in the UK as Violent Streets, offered a crystallisation of many of the themes of Mann’s later work. Although Mann’s earlier television work (for example, his scripts for Starsky & Hutch, 1975-8, and Police Story, 1973-7) evidenced a fascination with the relationships between the police and criminals, Thief established Mann’s focus on the work of professional criminals who are defined by their work and the obsessive members of law enforcement who seek to catch them – which would become a defining characteristic of many of Mann’s subsequent films. Thief also helped to establish Mann’s signature style, and like many of Mann’s subsequent pictures, at the time of its release Thief was criticised as privileging style over substance.

The film begins with an expertly-planned and executed heist committed by Frank (James Caan) and his partner Barry (James Belushi). Following this, Frank’s fence Joe Gags (Hal Frank) tries to arrange a sitdown between Frank and those buying his ‘merch’ (‘These people want to meet you. They’re stand-up guys’), something Frank is unwilling to commit to (‘If I want to meet people, I’ll go to a fucking country club’). Frank asks Barry to tail Gags to ensure that the handover of the merchandise goes according to plan. However, Gags is killed after the exchange: as Barry tells Frank, Gags ‘took a walk through a twelfth floor window. He’s splattered all over the sidewalk’. The merchandise is in the hands of the buyer, and so it seems is Frank’s money, $185,000. This event forces Frank to make direct contact with the buyer of his ‘merch’. Frank storms into the offices of Attaglia (Tom Signorelli), his buyer, who uses a business (L & A Plating) as a front for his criminal activity – much as Frank himself owns a car dealership, using this as a legitimate front for his work as a professional thief.  Frank threatens Attaglia. However, Attaglia is mobbed-up, and in the meeting that Frank sets up to collect his money from Attaglia, Frank is introduced to Leo (Robert Prosky), who introduces himself as ‘the Bank’: Leo payrolls many of the big heists within the city (‘I’m the bank for half the city’). Leo offers Frank a job (‘You want to put down contract scores all over the country, working for me?’), but Frank resists, affirming his status as a solo artist (‘I am self employed. I am doin’ fine. I don’t deal with egos. I am Joe-the-boss of my own body, so what the fuck do I have to work for your for?’). However, Leo offers to make Frank ‘a millionaire in four months’, and Frank sees this as an opportunity to make one or maybe two big scores before backing out of the lifestyle for good. However, as Frank acknowledges, bigger scores for Leo come with bigger risk: as if to confirm this, Mann reveals to us that Leo is under surveillance by the police, and now that Frank has met with Leo, Frank – who has previously been off the radar – is now a person of interest for the Chicago Police Department. Frank threatens Attaglia. However, Attaglia is mobbed-up, and in the meeting that Frank sets up to collect his money from Attaglia, Frank is introduced to Leo (Robert Prosky), who introduces himself as ‘the Bank’: Leo payrolls many of the big heists within the city (‘I’m the bank for half the city’). Leo offers Frank a job (‘You want to put down contract scores all over the country, working for me?’), but Frank resists, affirming his status as a solo artist (‘I am self employed. I am doin’ fine. I don’t deal with egos. I am Joe-the-boss of my own body, so what the fuck do I have to work for your for?’). However, Leo offers to make Frank ‘a millionaire in four months’, and Frank sees this as an opportunity to make one or maybe two big scores before backing out of the lifestyle for good. However, as Frank acknowledges, bigger scores for Leo come with bigger risk: as if to confirm this, Mann reveals to us that Leo is under surveillance by the police, and now that Frank has met with Leo, Frank – who has previously been off the radar – is now a person of interest for the Chicago Police Department.

In the midst of this, Frank begins a relationship with Jessie (Tuesday Weld) which, driven by the advice of his prison friend Okla (Willie Nelson), is driven by complete honesty: at the outset of their relationship, Frank reveals to Jessie that he is a thief and an ex-con. Jessie, it is revealed, has had an equally turbulent life. But she is unable to carry a child, and having a son is an integral part of Frank’s dream for his future, symbolised in a photo collage that he carries with him in his wallet. Frank also makes moves to have Okla’s conviction quashed, so that Okla, who is gravely ill, may live his last days outside prison. Sadly, Okla dies – but after being released from prison. (‘That’s the big thing: not to die in the joint’, Frank tells Jessie matter-of-factly.) As a way of bankrolling his dream life with Jessie, Frank agrees to do a job for Leo, breaking into the Bank of California. Leo, meanwhile, helps Frank to acquire a house in the suburbs, and he also helps Frank and Jessie to obtain a son, from a mother who is willing to sell her new baby, who they name after Okla. (‘It’s not the kid’s fault that his mother’s an asshole; and you’re not buying the mother’, Leo tells Frank after Frank’s first reaction to the idea of buying a child on the black market is to express how distasteful it is.) However, Frank finds the Chicago PD to be on his case, threatening him with violence and incarceration if he doesn’t pay them protection money, and after the successful completion of the heist at the Bank of California he also finds out just how difficult it is to extricate himself from Leo’s business. Leo refuses to give Frank his part of the heist in cash, telling Frank that the money has been invested on his behalf, and reminding Frank that his dream of domesticity has been bought because of his association with Leo (‘Don’t you get it, you prick? You got a home, car, business, family, and I own the paper on your whole fuckin’ life’). Leo threatens Frank’s family, including his baby son; Frank responds by sending Jessie and the baby away, alienating Jessie in order to save her and their son, and seeking revenge against Leo in the same slick manner with which he has conducted the heists.  Thief is claimed to be based on Frank Hohimer’s 1975 novel The Home Invaders, which Hohimer, himself a convicted cat burglar and alleged murderer, wrote whilst in prison. However, little of Hohimer’s scenario remains within the film, other than a focus on the mechanics of crime and some lines of dialogue which are based quite closely on some of the content of Hohimer’s novel. Thief is claimed to be based on Frank Hohimer’s 1975 novel The Home Invaders, which Hohimer, himself a convicted cat burglar and alleged murderer, wrote whilst in prison. However, little of Hohimer’s scenario remains within the film, other than a focus on the mechanics of crime and some lines of dialogue which are based quite closely on some of the content of Hohimer’s novel.

Mann hired John Santucci, a former thief and ex-convict, as a technical advisor; Santucci played one of the detectives in the film, and rumour has it that some of the tools used by Frank in his heists actually belonged to Santucci (Badham & Modderno, 2006: 70). Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the law, Dennis Farina, in reality a former officer in the burglary division of the Chicago Police Department who had acted as a police consultant on some of Michael Mann’s television work, played one of Leo’s hired guns. Steven Rybin has suggested that in casting former crooks as cops and former cops as crooks, Mann ‘suggests the fragile line between the enforcer and the transgressor of the law’, a theme which would reappear in many of his later films: for example, in the relationship between Will Graham (William Petersen) and Dr Hannibal Lecktor (Brian Cox) in Manhunter (1986), between Lieutenant Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) and thief Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) in Heat (1995) and the undercover work of Crockett and Tubbs in Miami Vice (both the television series and the 2006 film version). John Badham has suggested that by confusing the roles of police and villains in Thief, Mann offered a reflection of the reality within ‘inner-city Chicago. They [the police and the criminals] all grew up in the same neighborhood. They all knew each other. Some were even married to each other’s cousins. It wasn’t two alien cultures (Badham & Modderno, op cit.: 70). Both Thief and Mann’s later films L.A. Takedown (1989, produced for television) and Heat (a big-screen remake of L.A. Takedown) are, at their core, heist films. As such, they are situated in a long lineage of heist films which include films noirs such as The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) and Armored Car Robbery (Richard Fleischer, 1950) and stylish European variants such as Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le cercle rouge (1970) and Henri Verneuil’s Le Casse (The Burglars, 1971). As Jonathan Rayner suggests, heist films examine ‘the motivation, conception, preparation, execution and aftermath of a high-profile “score”’, which may be ‘a bank robbery, complex safecracking operation or hold-up’ (2013: np). The growth of heist films, with their focus on criminal protagonists and the mechanics of crime, during the 1950s and 1960s is often cited as an outcome of the relaxation of the Motion Picture Production Code and the shift away from the kind of pre-censorship facilitated by the Production Code towards the system of age-based classification that replaced it in 1968. The heist film offered a way of revisiting some of the themes of the early 1930s gangster films (such as William A Wellman’s The Public Enemy, 1931) whose perceived immoralities led to the creation of the Hays Code.  From the heist film, Rayner suggests, Mann’s work (not just Thief) takes its ‘abiding fixation on proficiency and a professional unity of action in pursuit of a specified goal’ (ibid.). In gangster films, and Mann’s work, the ‘dominant and defining element of male characters’ is the ‘enhancement of professional expertise’ and the ‘realisation of personal (masculine) identity is accomplished through vocational activity’ (ibid.). Another element that Mann’s pictures develop from the traditional heist film is the depiction of the ‘crew’ or criminal group as a substitute family. In Thief, Frank’s prison buddy Okla acts essentially as a father figure to Frank and figures in the photo collage that Frank keeps as a symbol of his dreams for the future. In subsequent films by Mann, including Heat and Public Enemies (2009), associations made in prison provide the ‘basis for long-term loyalt[ies] and identity’ (ibid.). In Mann’s world, police and criminals are united by ‘a devotion to work which is not, or not solely, derived from the assurance of financial reward’ and their emphasis on the twin values of ‘professionalism and sacrifice’ (ibid.). When Frank is captured by the Chicago PD and beaten up by a group of detectives, who are more interested in extorting him than arresting him, one of the men admits his admiration for Frank but questions his bullheadedness: ‘You’re real good’, the detective says, ‘No violence. Strictly professional. I’d probably like you. Like to go to the track, ball games. Stuff like that, you know? Frank, there’s ways of doin’ things that round off the corners, make life easy for everybody. What’s wrong with that? There’s plenty to go around [….] But no, you got to come on like a stiff prick! Who the fuck do you think you are?’ From the heist film, Rayner suggests, Mann’s work (not just Thief) takes its ‘abiding fixation on proficiency and a professional unity of action in pursuit of a specified goal’ (ibid.). In gangster films, and Mann’s work, the ‘dominant and defining element of male characters’ is the ‘enhancement of professional expertise’ and the ‘realisation of personal (masculine) identity is accomplished through vocational activity’ (ibid.). Another element that Mann’s pictures develop from the traditional heist film is the depiction of the ‘crew’ or criminal group as a substitute family. In Thief, Frank’s prison buddy Okla acts essentially as a father figure to Frank and figures in the photo collage that Frank keeps as a symbol of his dreams for the future. In subsequent films by Mann, including Heat and Public Enemies (2009), associations made in prison provide the ‘basis for long-term loyalt[ies] and identity’ (ibid.). In Mann’s world, police and criminals are united by ‘a devotion to work which is not, or not solely, derived from the assurance of financial reward’ and their emphasis on the twin values of ‘professionalism and sacrifice’ (ibid.). When Frank is captured by the Chicago PD and beaten up by a group of detectives, who are more interested in extorting him than arresting him, one of the men admits his admiration for Frank but questions his bullheadedness: ‘You’re real good’, the detective says, ‘No violence. Strictly professional. I’d probably like you. Like to go to the track, ball games. Stuff like that, you know? Frank, there’s ways of doin’ things that round off the corners, make life easy for everybody. What’s wrong with that? There’s plenty to go around [….] But no, you got to come on like a stiff prick! Who the fuck do you think you are?’

Like Neil McCauley in Thief, Frank hopes to make one last big score before backing off to retire with his new family. This encourages the audience to sympathise with both characters and it also makes their fate, when the twin forces of law and criminality conspire against them despite the professionalism of their work, all the more tragic. Rayner states ‘there is a repeated and disconcerting encouragement of sympathy for the criminals fated not to achieve the peace, escape and normalcy their violent antisocial behaviour is intended to yield’ (ibid.). Frank pursues criminal activity as a means to achieving his domestic dream; Leo enables Frank to achieve this dream of domesticity after Frank and Jessie find that they are unable to adopt a child owing to Frank’s status as an ex-con, but in doing so Leo places Frank in his pocket: ‘I own the paper on your whole fuckin’ life’, Leo tells Frank towards the end of the picture, ‘I own you. I run you. You work until you are burned-out, you’re busted or you’re dead. You got it?’ Frank’s dream is symbolised through the photo collage Frank keeps in his wallet, and when Frank realises that he has only achieved this dream through compromising his integrity as an individual who works outside the corporate sphere, and that he is no longer ‘Joe-the-boss of my own body’, he screws up this collage and discards it immediately after burning down his car dealership and just before laying siege to Leo’s house as a means of severing his ties with the mob – thus preventing Leo from posing a threat to Jessie and the baby, who Frank has already alienated with the intention of ensuring that Jessie flees the city to safety.  Frank is a loner by nature, an institutionalised personality. In a long monologue delivered to Jessie, he tells her that after being raised in care, he was incarcerated at the age of 20 for an act of petty theft. Whilst in prison, he was constantly threatened with rape and was forced to protect himself against two other inmates, an act which resulted in a charge of manslaughter. Frank was finally released from prison at the age of 30. When Frank visits Okla in prison, Okla and Frank reflect on how the prison population has changed: Okla tells Frank that the prison population is seeing a lot of knifings owing to a proliferation of drugs. ‘You wouldn’t believe the quality of people they’re puttin’ in here these days’, Okla tells Frank, ‘Ten or fifteen years ago, they’d have dumped them in a funny farm somewhere. Rapists, child molesters, they put ‘em right in with the mainstream population. Used to be someone like that, if they lasted five days it’d be a world record. Perverse’. Frank tells Okla about Jessie, stating his dilemma: lie to her about his past or tell her the truth. ‘Lie to no-one’, Okla advises him, ‘If they’re somebody close to you, you’re gonna ruin it with a lie. And if they’re a stranger, who the fuck are they you gotta lie to?’ Frank is a loner by nature, an institutionalised personality. In a long monologue delivered to Jessie, he tells her that after being raised in care, he was incarcerated at the age of 20 for an act of petty theft. Whilst in prison, he was constantly threatened with rape and was forced to protect himself against two other inmates, an act which resulted in a charge of manslaughter. Frank was finally released from prison at the age of 30. When Frank visits Okla in prison, Okla and Frank reflect on how the prison population has changed: Okla tells Frank that the prison population is seeing a lot of knifings owing to a proliferation of drugs. ‘You wouldn’t believe the quality of people they’re puttin’ in here these days’, Okla tells Frank, ‘Ten or fifteen years ago, they’d have dumped them in a funny farm somewhere. Rapists, child molesters, they put ‘em right in with the mainstream population. Used to be someone like that, if they lasted five days it’d be a world record. Perverse’. Frank tells Okla about Jessie, stating his dilemma: lie to her about his past or tell her the truth. ‘Lie to no-one’, Okla advises him, ‘If they’re somebody close to you, you’re gonna ruin it with a lie. And if they’re a stranger, who the fuck are they you gotta lie to?’

After revealing to Jessie the truth about his past, Frank tells her of his coping strategy, based on the principle of self-negation. ‘You don’t count months and years [in prison]’, he tells her, ‘You don’t do time that way [….] You gotta forget time. You gotta not give a fuck if you live or die. You gotta get to where nothin’ means nothin’. However, the world outside prison is filled with promise, but Frank has limited time to achieve his dream of a stable domestic life: ‘I have run out of time’, he tells Jessie, ‘I can’t work fast enough to catch up. I can’t run fast enough to catch up. All I can do is my magic act’ – his work as a professional thief, with a strict code of ethics (‘No cowboy shit. No home invasions’, he informs Leo). However, the worldview of self-negation that helped Frank survive in prison originated before he was incarcerated at the age of 20, during his childhood. When Frank and Jessie try to adopt a child, later in their relationship, they find themselves turned down because of Frank’s past as an ex-convict. Frank responds angrily, telling the woman on the desk, ‘I was state-raised and this is a dead place. A child in eight by four green walls. After a while you tell the walls, “My life is yours”’. Frank’s life on the outside has been driven by a desire to ensure that he has ownership of his life and destiny; he resists the corporate mentality represented by Leo but sees it as a way of achieving his dream. However, he reminds Leo that ‘I do not mix apples and oranges’ – but this attempt to keep his work for Leo and his personal life separate is frustrated when Leo helps Frank and Jessie find a child.  When the group of detectives who have had Frank and Leo under surveillance, and who attempt to subject Frank to a shakedown, capture Frank, they hold him in a room that resembles that described by Frank in the adoption centre – an ‘eight by four’ room with green walls. The detectives beat Frank, surrounding him and towering over him. The imagery here taps into Frank’s descriptions of his childhood in care and the beatings and threats of rape he experienced in prison, both at the hands of the other prisoners and at the behest of one particularly vicious bull. (Even the language used by the detectives in this sequence is suggestive of sexual assault, with one of the detectives referring to Frank as ‘like a stiff prick’ and another threatening several times that he will be ‘up your ass’.) Mann seems to suggest that even on the outside of prison, with a front as a legitimate businessman, Frank is subjected to the same old treatment he experience both as a child in care, and as a young adult in prison. The cycle of violence and exploitation continues, perpetuated by figures of authority and members of the criminal underworld alike – the two worlds are interchangeable, both based on the principle of exploitation and the alienation of the worker (Frank) from the fruits of his labour (‘I can see my money is still in your pocket, which is the yield from my labour’, Frank tells Leo after the Bank of California heist). Shortly after, Leo advises Frank that, ‘You know, when you have trouble from the cops, you pay them off, because that’s the way things are done. But not you, huh?’ ‘No’, Frank tells Leo, ‘They don’t run me, and you don’t run me’. When Frank demands his money from Leo, Leo reacts badly, highlighting Frank’s worldview: ‘You don’t want to work for me? What’s wrong with you? [….] You one of those burned-out, demolished wackos in the joint? You’re scare because you don’t give a fuck. But don’t come on to me now with your jailhouse bullshit, because you are not that guy’. When the group of detectives who have had Frank and Leo under surveillance, and who attempt to subject Frank to a shakedown, capture Frank, they hold him in a room that resembles that described by Frank in the adoption centre – an ‘eight by four’ room with green walls. The detectives beat Frank, surrounding him and towering over him. The imagery here taps into Frank’s descriptions of his childhood in care and the beatings and threats of rape he experienced in prison, both at the hands of the other prisoners and at the behest of one particularly vicious bull. (Even the language used by the detectives in this sequence is suggestive of sexual assault, with one of the detectives referring to Frank as ‘like a stiff prick’ and another threatening several times that he will be ‘up your ass’.) Mann seems to suggest that even on the outside of prison, with a front as a legitimate businessman, Frank is subjected to the same old treatment he experience both as a child in care, and as a young adult in prison. The cycle of violence and exploitation continues, perpetuated by figures of authority and members of the criminal underworld alike – the two worlds are interchangeable, both based on the principle of exploitation and the alienation of the worker (Frank) from the fruits of his labour (‘I can see my money is still in your pocket, which is the yield from my labour’, Frank tells Leo after the Bank of California heist). Shortly after, Leo advises Frank that, ‘You know, when you have trouble from the cops, you pay them off, because that’s the way things are done. But not you, huh?’ ‘No’, Frank tells Leo, ‘They don’t run me, and you don’t run me’. When Frank demands his money from Leo, Leo reacts badly, highlighting Frank’s worldview: ‘You don’t want to work for me? What’s wrong with you? [….] You one of those burned-out, demolished wackos in the joint? You’re scare because you don’t give a fuck. But don’t come on to me now with your jailhouse bullshit, because you are not that guy’.

Video

Thief was the film in which Mann began to practise his signature aesthetic, which has often been accused by Mann’s detractors of privileging ‘style’ over ‘substance’. With regards to Thief, Vincent Canby noted suggested that the film’s photography was ‘pretty enough to be framed and hung on a wall, where, of course, good movies don’t belong’ (quoted in Rybin, op cit.: 24). Bringing to mind the ‘cinema of process’ opening sequence of Le Samourai (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967), in which Jef Costello (Alain Delon) is depicted stealing a car in loving detail (rather than in the condensed action associated with most Hollywood films), the opening sequence of Thief establishes the film’s approach to its material. The film’s titles are presented as neon blue lettering on a plain black background, with the film’s synth score by Tangerine Dream playing in the background. Rain is shown cascading between two tall buildings as the camera tilts down to reveal city streets slick with rain. In a series of medium shots and tight close-ups, Frank wordlessly works a drill, punching out a lock. Via a zoom achieved in postproduction, Mann takes us into the hole bored by the drill. Both this sequence and the later robbery of the Bank of California are depicted in long sequences that, in their focus on the minute details of the execution of each heist, recall the central heist sequences in Rififi and Le cercle rouge. Thief was the film in which Mann began to practise his signature aesthetic, which has often been accused by Mann’s detractors of privileging ‘style’ over ‘substance’. With regards to Thief, Vincent Canby noted suggested that the film’s photography was ‘pretty enough to be framed and hung on a wall, where, of course, good movies don’t belong’ (quoted in Rybin, op cit.: 24). Bringing to mind the ‘cinema of process’ opening sequence of Le Samourai (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1967), in which Jef Costello (Alain Delon) is depicted stealing a car in loving detail (rather than in the condensed action associated with most Hollywood films), the opening sequence of Thief establishes the film’s approach to its material. The film’s titles are presented as neon blue lettering on a plain black background, with the film’s synth score by Tangerine Dream playing in the background. Rain is shown cascading between two tall buildings as the camera tilts down to reveal city streets slick with rain. In a series of medium shots and tight close-ups, Frank wordlessly works a drill, punching out a lock. Via a zoom achieved in postproduction, Mann takes us into the hole bored by the drill. Both this sequence and the later robbery of the Bank of California are depicted in long sequences that, in their focus on the minute details of the execution of each heist, recall the central heist sequences in Rififi and Le cercle rouge.

Mann has a well-deserved reputation for tinkering with his films after their release. Manhunter, Heat, Miami Vice and The Last of the Mohicans (1991) all exist in a number of different versions, something which can be frustrating for fans of Mann’s work. For the 1995 LaserDisc release, Mann revisited Thief and made a number of changes, abbreviating some scenes (including Frank, Jessie and Barry’s brief trip to San Diego and the argument between Frank and Jessie that results in Jessie leaving with the baby) and playing with the speed of the shots at the climax of the film, in which Frank takes on Leo’s hired guns. This version of the film was released on DVD. For the 2013 release of Thief by Criterion (on DVD and Blu-ray), Mann reversed some of these editorial decisions but decided to rework the film’s aesthetic, giving the film a steely blue tint that emphasised the coldness of the world(s) in which Frank moved. However, this had the effect of negating some of the juxtapositions within the film’s mise-en-scène: for example, in one scene Frank enters a bar, and his face and clothes are placed in contrast with the emerald green tinting of the window behind him; in another scene, Frank makes a phone call at a public telephone at night, and his face (on the right hand side of the frame) is juxtaposed with the deep blacks of the night behind him and the steely greys and blues of the telephone. In both scenes, the contrast between Frank and his environment is lost (or at the very least, heavily muted) in the director’s cut that’s presented on the Criterion Blu-ray. For this release, Arrow have included the same director’s cut that was released on Blu-ray by Criterion in the States, sourced from a 4k scan, and, on a separate disc, the original theatrical cut – minus the amendments that Mann made to the film for its 1995 LaserDisc release, and also minus the blue tint that features on the director’s cut. However, the theatrical cut is sourced from a much older scan, and this is reflected in the presentation, which doesn’t quite have the depth and richness of detail that’s present in the 4k scan of the newer director’s cut. Both versions of the film are in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The director’s cut has a running time of 124:36 mins; the theatrical cut runs for 123:09 mins. The director’s cut, on disc one, for all intents and purposes looks pretty much identical to the Criterion Blu-ray released in 2013. It’s the same presentation, based on the same 4k scan, albeit with a different encode. (The film takes up approximately 37Gb of space.) An impressive level of detail is on display, and there’s a great deal of depth to the photography (for example, see the opening sequence, with its persistent rainfall at nighttime, lights reflecting in the pools of water forming on the city streets). Contrast levels are excellent, and the film has an organic, filmlike appearance with a natural level of film grain which is resolved nicely within the encode. In comparison with the director’s cut, the theatrical cut on disc two (which takes up approximately 36Gb of space on a dual-layered disc) has a much more naturalistic palette. The level of detail is below that present on the 4k scan of the director’s cut. However, it’s still an impressive presentation, with a strong sense of depth to the image – exhibited from the opening sequence’s depiction of city streets, at night, drenched in rain. The deep focus of these external nighttime scenes is often placed in contrast with the shallow focus photography used in the nighttime scenes set in buildings, etc – but in some of these scenes, Mann uses split-diopter shots to give the illusion of an increased depth of field. The level of contrast in this presentation is impressive, which is good considering how much low light photography there is within the film. The image has a strong organic, film-like appearance, with a natural level of grain. In some scenes, there seems to be some evidence of digital noise reduction, but nothing too overwhelming or detrimental. The theatrical cut also exhibits some minor cropping (mostly on the left-hand side of the frame) in comparison with the director’s cut, which results in slightly tighter compositions. Images comparing the director’s cut and the theatrical cut can be found at the bottom of this review. Please note that these aren’t exact matches but should illustrate the differences in terms of the two presentations’ palettes.

Audio

On disc one, the director’s cut has an option of a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both of these are clear and audible throughout. The newer 5.1 track has a softer mixing of dialogue and ambient sounds and gives the music a haunting prominence, but on balance both tracks are equally pleasing. The presentation of the film on this disc is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. On disc two, the theatrical cut is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is surprisingly dynamic, something which is evident from the opening sequence in which the sound of falling rain fills the soundscape. It’s a rich, pleasing track which is also accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

Disc one includes a commentary by Michael Mann and James Caan, which is the same commentary that was recorded for the 1995 LaserDisc and which appeared on the subsequent DVD releases. (At the end of the film, Caan reminds us that Mann is ‘currently’ working ‘on a film with Pacino and De Niro’ – clearly Heat.) It’s an excellent commentary, with Mann and Caan clearly comfortable in each other’s presence and offering some strong insight into the film’s themes and the technicalities of its production. It’s fun to listen to too (reflecting on the involvment of people like Santucci in the production of the movie, Caan at one point quips that the label ‘technical adviser’ is ‘a fancy name for “thief”’). There are some significant gaps in the conversation, as was often the case with LaserDisc era commentaries. The Directors: ‘Michael Mann’ (59:28). This 2001 television documentary takes a look back at Mann’s career as a filmmaker. ‘Stolen Dreams’ (14:32). This is a new and exclusive interview with James Caan, recorded in 2014. Caan reflects on his preparation for the role and the lengths which he went to to ensure that the gun-handling within the film was accurate. Cine regards: ‘Hollywood USA – James Caan’ (24:38). This short piece is from the French television series Cine regards and features an interview with Caan conducted after filming on Thief had wrapped. The image is presented in 1.33:1 with burnt-in French subtitles. The Art of the Heist: An Examination of ‘Thief’ (66:29). This is a new and exclusive video essay analysing Thief, put together by F X Feeney, the American writer and filmmaker. It’s a thorough and indepth examination of the film, well-researched and nicely-presented. Theatrical trailer (1:53). On disc two, the theatrical cut includes an isolated music and effects track (in LPCM 2.0 stereo).

Overall

Mann’s Thief is an amazing film, albeit one which divided critics at the time of its release (and, no doubt, continues to divide viewers). The accusations that the film is an example of style over substance seem extraordinarily pat in light of the ways in which Hollywood cinema has developed since 1981. The film’s examination of Frank’s resistance to the corporate hegemony and his fierce individuality (that he is ‘Joe-the-boss of my own body’) has resonance for many areas of modern life, and could be taken as a metaphor for wider social issues, and even within the context of the film is presented not without irony (Frank neglects to mention that he too is a boss of others – of the employees within his car dealership, who as an early sequence shows he rudely ignores when they address him). Mann’s Thief is an amazing film, albeit one which divided critics at the time of its release (and, no doubt, continues to divide viewers). The accusations that the film is an example of style over substance seem extraordinarily pat in light of the ways in which Hollywood cinema has developed since 1981. The film’s examination of Frank’s resistance to the corporate hegemony and his fierce individuality (that he is ‘Joe-the-boss of my own body’) has resonance for many areas of modern life, and could be taken as a metaphor for wider social issues, and even within the context of the film is presented not without irony (Frank neglects to mention that he too is a boss of others – of the employees within his car dealership, who as an early sequence shows he rudely ignores when they address him).

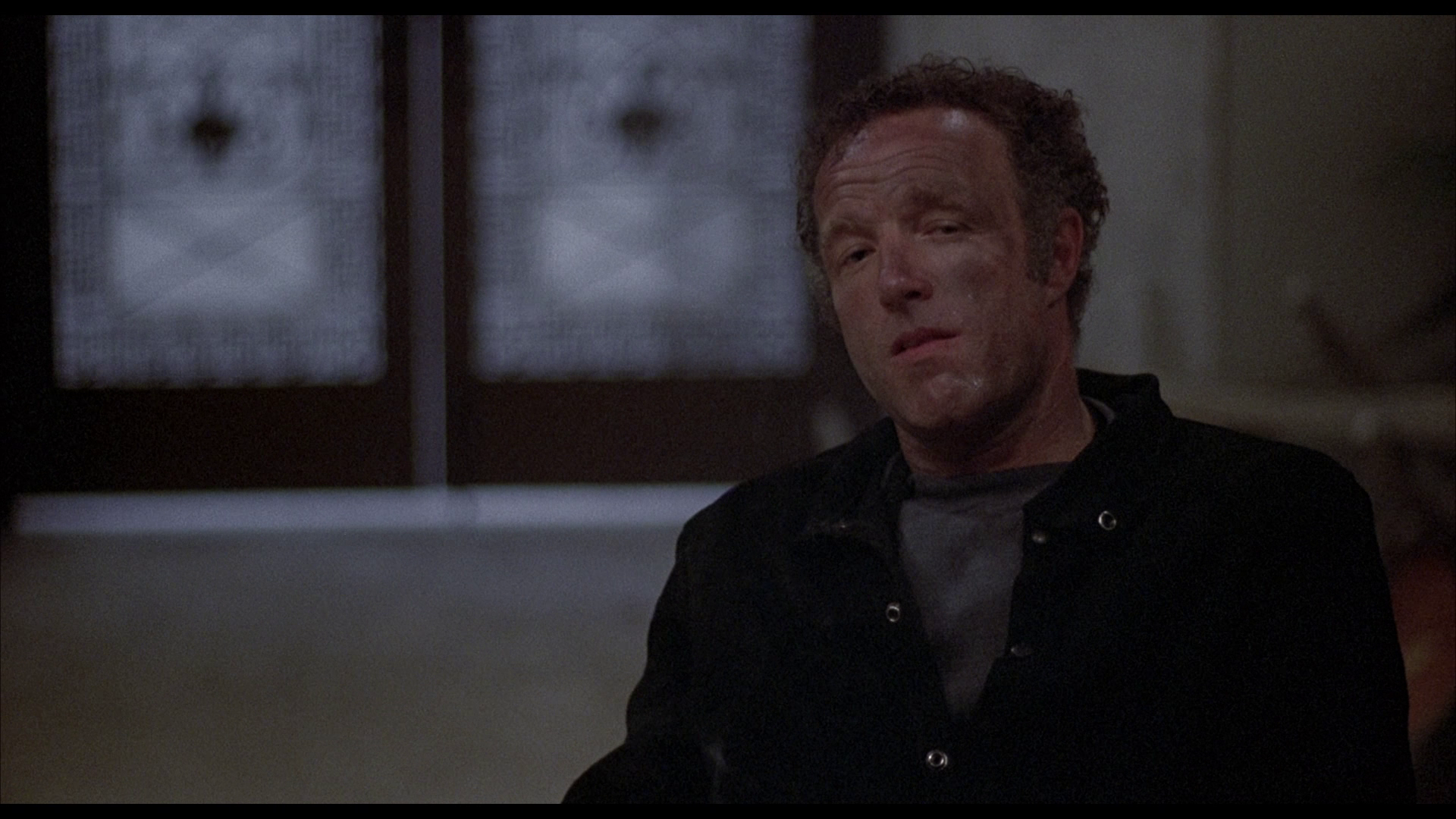

Whether one prefers the newer director’s cut, with its steely blue tint, or the original theatrical cut is a matter of opinion. Thankfully, Arrow have seen fit to include both in this set. The new 4k scan of the director’s cut is the most pleasing presentation of the two, but the HD presentation of the theatrical cut, whilst based on an older scan with more obvious limitations, is no slouch either and is clearly a head and shoulders improvement over the previously-available DVDs. Whilst the Criterion disc released in the US, which only contains the new director’s cut, includes some exclusive interviews, Arrow's new release contains an equally impressive range of exclusive contextual material. In sum, this is a stunning release and is highly recommended. References: Badham, John & Modderno, Craig, 2006: I’ll Be in My Trailer: The Creative Wars Between Directors and Actors. California: Michael Wiese Productions Rayner, Jonathan, 2013: The Cinema of Michael Mann: Vice and Vindication. New York: Wallflower Press Rybin, Steven, 2013: Michael Mann: Crime Auteur. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut:

Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut:

Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut:

Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut:

Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut:

Director’s Cut:

Theatrical Cut

|

|||||

|