|

|

Last Seduction (The)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th January 2015). |

|

The Film

The Last Seduction (John Dahl, 1994)  During the middle 1990s, the revival of film noir motifs was in full swing. Whether one referred to the films as examples of ‘neo-noir’ or ‘noir lite’, there was a clear resurgence of films that revisited some of the concerns of films noir. However, much as the limits of traditional film noir are notoriously nebulous and defy easy classification, there is of course some debate surrounding the beginnings of neo-noir, with some suggesting that any film noir-like picture made after the ‘classic’ period (usually seen as ending with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil in 1958) is an example of neo-noir. This of course would include 1960s and 1970s-era colour films that explore noir-like subject matter, such as Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Peter Yates, 1973). An alternate perspective suggests that neo-noir films can be identified by a postmodern sense of nostalgic pastiche that looks back to the era of ‘classic’ films noir. From this point of view, neo-noir ‘proper’ begins with films of the 1980s that combine noir-like themes and iconography with narratives that look back to the period of classic films noir, such as Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) and The Grifters (Stephen Frears, 1990). During the middle 1990s, the revival of film noir motifs was in full swing. Whether one referred to the films as examples of ‘neo-noir’ or ‘noir lite’, there was a clear resurgence of films that revisited some of the concerns of films noir. However, much as the limits of traditional film noir are notoriously nebulous and defy easy classification, there is of course some debate surrounding the beginnings of neo-noir, with some suggesting that any film noir-like picture made after the ‘classic’ period (usually seen as ending with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil in 1958) is an example of neo-noir. This of course would include 1960s and 1970s-era colour films that explore noir-like subject matter, such as Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967) and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Peter Yates, 1973). An alternate perspective suggests that neo-noir films can be identified by a postmodern sense of nostalgic pastiche that looks back to the era of ‘classic’ films noir. From this point of view, neo-noir ‘proper’ begins with films of the 1980s that combine noir-like themes and iconography with narratives that look back to the period of classic films noir, such as Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) and The Grifters (Stephen Frears, 1990).

Whichever way one defines it, the resurgence of film noir motifs (a focus on the underworld, an examination of femmes fatales and fall guys – and even the occasional homme fatale, chiaroscuro lighting and expressionistic use of the camera) was particularly noticeable during the late-1980s and early-1990s. Some of the neo-noir films of this period were sourced from examples of hard-boiled crime literature, such as James Foley’s 1990 adaptation of Jim Thompson’s 1955 novel After Dark, My Sweet, Michael Oblowitz’ This World, Then the Fireworks (1997, based on a Jim Thompson short story), Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress (1995, adapted from Walter Mosley’s novel), Dennis Hopper’s The Hot Spot (1990, from Charles Williams’ novel) and Curtis Hanson’s L. A. Confidential (1997, based on the novel by James Ellroy). Others, such as the Wachowskis’ Bound (1995), Peter Medak’s Romeo Is Bleeding (1993), Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (1992) or Carl Colpaert’s Delusion (1991), were based on original material which offered an obvious pastiche of elements of classic films noir. However, one aspect which many of the neo-noir films of this period is an increasing emphasis on erotic content; and of course, throughout the 1990s neo-noir would increasingly overlap with the world of the straight-to-video erotic thriller, something which Linda Ruth Williams has highlighted in her book The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema (2005): Williams reminds us that ‘whilst not all neo-noirs are erotic thrillers, many erotic thrillers are shot through with a postmodern noir or “white noir”’ (Williams, 2005: 35).  The Last Seduction, anchored by Linda Fiorentino’s fiery performance as a prototypical femme fatale (who happily describes herself as ‘a total fucking bitch’), tells a story that could be ripped from the pages of a lost James M Cain novel. Fiorentino plays Bridget Gregory, who as the film opens is shown presiding over a New York telesales office in which the employees are attempting to sell Liberty Dollar-type currency to unsuspecting punters. As the office manager, Fiorentino’s methods of motivating the telemarketers extends to humiliating her colleagues (‘You maggots sound like suburbanites’), referring to them as ‘eunuchs’ and ‘bastards’. Meanwhile, Bridget’s husband Clay (Bill Pullman) is selling pharmaceutical cocaine on the street, to the tune of $800,000. Clay intends that $100,000 of this money be used to pay off the loan shark who is threatening Clay with $10,000 a week interest and, if Clay doesn’t pay up, physical violence. The Last Seduction, anchored by Linda Fiorentino’s fiery performance as a prototypical femme fatale (who happily describes herself as ‘a total fucking bitch’), tells a story that could be ripped from the pages of a lost James M Cain novel. Fiorentino plays Bridget Gregory, who as the film opens is shown presiding over a New York telesales office in which the employees are attempting to sell Liberty Dollar-type currency to unsuspecting punters. As the office manager, Fiorentino’s methods of motivating the telemarketers extends to humiliating her colleagues (‘You maggots sound like suburbanites’), referring to them as ‘eunuchs’ and ‘bastards’. Meanwhile, Bridget’s husband Clay (Bill Pullman) is selling pharmaceutical cocaine on the street, to the tune of $800,000. Clay intends that $100,000 of this money be used to pay off the loan shark who is threatening Clay with $10,000 a week interest and, if Clay doesn’t pay up, physical violence.

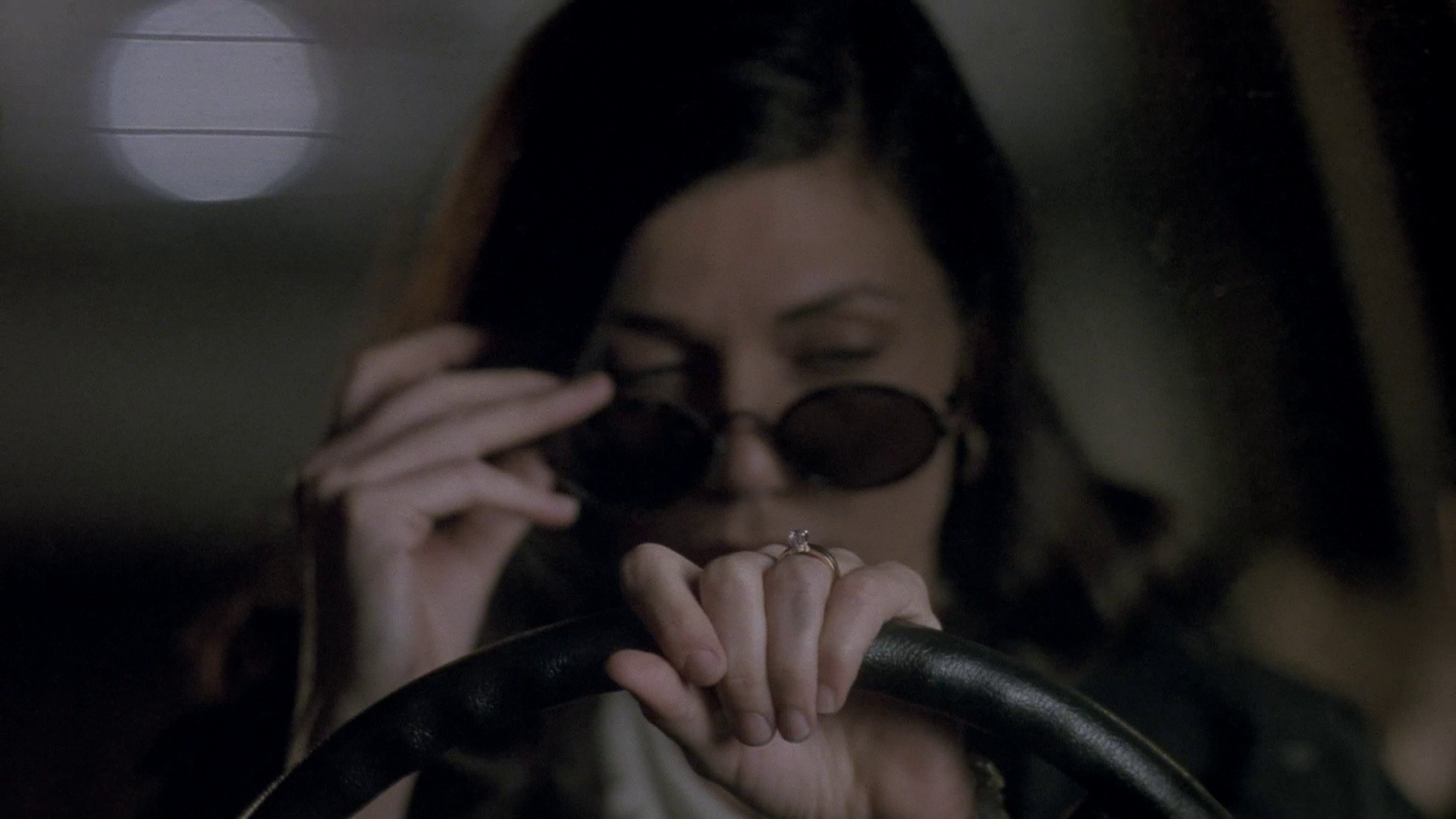

However, Bridget flees with the money that Clay has ‘earned’. On her way to Chicago, her car runs out of fuel in a small town named Beston, near Buffalo. There, at a bar called Ray’s, she meets Mike Swale (Peter Berg). Mike is a somewhat naďve man who, desperate to flee from his small town origins, made his way to Buffalo and, once there, found himself in an unhappy marriage to a woman named Trish; this precipitated Mike’s return to Beston, where he is deeply unhappy. After a brief ‘interview’ which sees Bridget inspecting Mike’s ‘manhood’ under a table in Ray’s bar and asking him about his sexual history, Mike becomes Bridget’s ‘designated fuck’. However, Mike wants more, seeing ‘big city’ Bridget as a way of escaping Beston once and for all, and Bridget’s life becomes complicated when she takes a job at a local telemarketing firm, under the assumed name ‘Wendy Kroy’ (‘New York’, backwards) and an accompanying story about escaping from a violent husband, and discovers that Mike also works there. Meanwhile, Clay has hired a private detective who traces Bridget’s whereabouts to Beston, and Clay has also deduced the pseudonym that Bridget is using. As Clay closes in, Mike pursues Bridget (who he knows as Wendy), and in Mike’s infatuation with her, Bridget/Wendy sees a chance to rid herself once and for all of Clay. She hatches a plan that will make it possible for her to lower Mike’s moral defenses to murder and emotionally blackmail him into killing Clay, thus allowing Bridget to escape with the money. The Last Seduction was Dahl’s third film as director; his two prior films, Kill Me Again (1989) and Red Rock West (1993), have also come to be seen as benchmarks of neo-noir. However, where Dahl himself had co-written both Kill Me Again and Red Rock West, The Last Seduction was written by Steve Barancik. (The original title of Barancik’s script was ‘Buffalo Girls’.) Dahl saw this as an opportunity to take a slightly different approach to the material, commenting that ‘what I loved about The Last Seduction was that I had the objectivity that I could not have had on those first two movies that I had done [Kill Me Again and Red Rock West]’ (quoted in Monaco, 2010: 10). Dahl has a preference for directing rather than writing: ‘What I like about not writing is having the objectivity to step back and I think that gives me the opportunity to do a better job of directing a film. That being said, I still write, but I’d rather direct someone else’s material’ (Dahl, quoted in ibid.). Famously, The Last Seduction premiered on HBO before achieving a theatrical release in the wake of positive response from the limited European cinema release. The fact that the film’s US premiere was on television meant that despite the praise lavished on the film (and, especially, Fiorentino’s performance, for which Fiorentino won the New York Film Critics Circle Best Actress award in 1994) by critics, The Last Seduction was prevented from being eligible for nomination in the Academy Awards. October Films and ITC attempted to take legal action to prevent the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from excluding The Last Seduction from their ‘eligibility list for Oscar voting’ but ‘the Academy maintained that when October Film [sic] and ITC sold the film to HBO in July, they knew it would kill the film’s Oscar eligibility’ (ibid.: 105).  The film opens with an opening shot that features a gargoyle, a stone bird of prey, looking down over the city as an iconic New York yellow cab passes below it. The suggestion of predatory behaviour is consolidated by Bridget’s behaviour later in the film. John Orr has suggested that in films noir of the 1990s that feature femmes fatales, these women are shown as ‘ambivalently oscillating between aggressive competitiveness and exultant victimhood’ (cited in Williams, 2005: 31). Throughout the film, Bridget uses her sexuality, and her comprehension of stereotypical female behaviour, to achieve her goals. When she arrives in Beston and applies for the job in the telesales office, she persuades the man interviewing her that she is a battered wife who is fleeing from an abusive husband, thus playing on the perception of woman-as-victim in order to railroad him into hiring her under the false name of ‘Wendy Kroy’ (which she believes will make her more difficult for Clay to track down). Similarly, after she has been responsible for the death of the private detective Clay has hired to bring her back to New York (whilst driving, she persuades him to show her his penis, and when he unbuckles his seatbelt to do so, she stops the car abruptly, sending him through the windscreen), she escapes charges and explains the private investigator’s state of undress by again playing to the perception of woman-as-victim: she tells the local police that the man intended to sexually assault her. Bridget also seduces Mike into committing the murder of Clay, pretending that she has committed a similar murder for money, to secure their future together; then, when Mike baulks at the suggestion that he should do the same (‘Wendy, maybe it’s my quaint small-town morals, but I don’t “do” murder’), she tells him that, ‘Yeah, well, you would if you loved me’. When Mike finally meets Clay, Clay deduces that Mike has been sent to kill him by Bridget’s manipulation of Mike’s desire for her: as Clay says, ‘I guess there aren’t many women fuck like her in Cowtown’. The film opens with an opening shot that features a gargoyle, a stone bird of prey, looking down over the city as an iconic New York yellow cab passes below it. The suggestion of predatory behaviour is consolidated by Bridget’s behaviour later in the film. John Orr has suggested that in films noir of the 1990s that feature femmes fatales, these women are shown as ‘ambivalently oscillating between aggressive competitiveness and exultant victimhood’ (cited in Williams, 2005: 31). Throughout the film, Bridget uses her sexuality, and her comprehension of stereotypical female behaviour, to achieve her goals. When she arrives in Beston and applies for the job in the telesales office, she persuades the man interviewing her that she is a battered wife who is fleeing from an abusive husband, thus playing on the perception of woman-as-victim in order to railroad him into hiring her under the false name of ‘Wendy Kroy’ (which she believes will make her more difficult for Clay to track down). Similarly, after she has been responsible for the death of the private detective Clay has hired to bring her back to New York (whilst driving, she persuades him to show her his penis, and when he unbuckles his seatbelt to do so, she stops the car abruptly, sending him through the windscreen), she escapes charges and explains the private investigator’s state of undress by again playing to the perception of woman-as-victim: she tells the local police that the man intended to sexually assault her. Bridget also seduces Mike into committing the murder of Clay, pretending that she has committed a similar murder for money, to secure their future together; then, when Mike baulks at the suggestion that he should do the same (‘Wendy, maybe it’s my quaint small-town morals, but I don’t “do” murder’), she tells him that, ‘Yeah, well, you would if you loved me’. When Mike finally meets Clay, Clay deduces that Mike has been sent to kill him by Bridget’s manipulation of Mike’s desire for her: as Clay says, ‘I guess there aren’t many women fuck like her in Cowtown’.

Hillary Nerroni suggests that along with a number of other contemporaneous films (for example, James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day, 1991, and Irwin Winkler’s The Net, 1995), The Last Seduction presents its female protagonist’s femininity as a masquerade ‘that can be removed because it is not intrinsic to the characters’ (2012: 95). Nerroni states that in Dahl’s film, ‘[e]verything about Bridget seems slightly off, or faked, because she employs her femininity’, which ‘does not seem “natural” but applied’ (ibid.; emphasis in original). Bridget ‘seems uninvested’ in her feminine ‘mask’, using it to achieve her goals but dropping it when alone (ibid.): she uses her femininity to distract the private detective that Clay has hired, before killing him; and she also uses it to manipulate Mike into agreeing to commit murder, provoking an argument with him and then, when he exits her house, the camera lingers on her in medium shot as her expression changes to a smirk. In one scene, Bridget highlights this performance of femininity for the benefit of Mike. Mike tries to persuade Bridget to allow him to get closer to her emotionally; with puppy dog eyes, she tells him, ‘I guess it’s because I’ve been hurt before. I don’t want to get close to anyone right now [….] I feel like maybe I could love you’. Mike is suckered in, but Bridget delivers an emotional blow to him by changing her expression and asking sarcastically, ‘Will that [her performance as a stereotypically vulnerable female] do?’ She ends her performance with the dictum: ‘Fucking doesn’t have to mean anything more than fucking’. The major conflict within the film is arguably as much between the big city (and its connotations of sophistication and cosmopolitanism) and the small town (and its associations with naďveté and simplicity) as it is between male and female. For Mike, Bridget represents his dream of escaping small town life in Beston for the big city. Mike has already left Beston for Buffalo, but after a brief and unsuccessful marriage – unsuccessful because the naďve Mike unknowningly married a transsexual - Mike returned to his small town origins. Bridget discovers this secret and finally goads Mike into committing Clay’s murder by sending him a letter that is ostensibly from Trish, his wife, stating that she is hoping to move to Beston to be with her husband. In his desperation to escape what he perceives as the humiliation that will follow the arrival of Trish, whose identity as a transsexual he has kept secret from his small-town friends, Mike agrees to Bridget’s plot. (He’s also persuaded by the fact that Bridget misrepresents Clay – in reality a medical student – as being an unscrupulous foreclosure lawyer who is happy to throw elderly ladies out of their homes.) When Mike is first shown talking to his friends in Ray’s bar, he tells them, ‘I just didn’t want to come back to this dead end town, is all [….] I went to Buffalo; it didn’t work out; I’m back’. A local girl, Stacy, flirts with Mike, who does not reciprocate. Mike’s friend Chris asks him, ‘What, you leave your dick in Buffalo?’ Mike responds by telling his friend, ‘Chris, these women are anchors [….] They’re planted here. You get too close to one, Beston’s got you for life’.  When Bridget enters the bar and brusquely orders a Manhattan, Mike notes her difference straight away. So does Ray, the owner, who ignores her request, to which Bridget asks loudly, ‘Who’s a girl got to suck round here to get a drink?’ Mike expresses his fascination in Bridget to his friends, who tell him, ‘City trash? What do you see in that?’ ‘Maybe a new set of balls’, Mike responds, highlighting both the way in which Bridget may offer a way out of Beston for him and the extent to which her behaviour challenges female stereotypes. After Mike (successfully) orders the drink for her, he tells Bridget she might find it easier to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. Bridget responds by telling him to ‘Fuck off’. She establishes the perceived inequality between herself (as a ‘sophisticated’ woman from the big city) and Mike (as a naďve man from a small town), telling him to ‘Go find yourself a nice little cowgirl, make nice little cow-babies and leave me alone’. Mike comes on to Bridget by playing on the sense of uncomplicated, animalistic sexuality associated with small towns and rural life: ‘I’m hung like a horse’, he tells her, simply; ‘Think about it’. Bridget reflects on this, calls Mike to her table and, like someone examining livestock that they are considering purchasing, puts her hands down his pants and inspects his penis at the table, whilst asking Mike about his sexual past. (His shocked response to her question, ‘Any men?’, is the first inkling of the insecurity that arises from the truth about his past relationship with Trish.) When Bridget enters the bar and brusquely orders a Manhattan, Mike notes her difference straight away. So does Ray, the owner, who ignores her request, to which Bridget asks loudly, ‘Who’s a girl got to suck round here to get a drink?’ Mike expresses his fascination in Bridget to his friends, who tell him, ‘City trash? What do you see in that?’ ‘Maybe a new set of balls’, Mike responds, highlighting both the way in which Bridget may offer a way out of Beston for him and the extent to which her behaviour challenges female stereotypes. After Mike (successfully) orders the drink for her, he tells Bridget she might find it easier to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’. Bridget responds by telling him to ‘Fuck off’. She establishes the perceived inequality between herself (as a ‘sophisticated’ woman from the big city) and Mike (as a naďve man from a small town), telling him to ‘Go find yourself a nice little cowgirl, make nice little cow-babies and leave me alone’. Mike comes on to Bridget by playing on the sense of uncomplicated, animalistic sexuality associated with small towns and rural life: ‘I’m hung like a horse’, he tells her, simply; ‘Think about it’. Bridget reflects on this, calls Mike to her table and, like someone examining livestock that they are considering purchasing, puts her hands down his pants and inspects his penis at the table, whilst asking Mike about his sexual past. (His shocked response to her question, ‘Any men?’, is the first inkling of the insecurity that arises from the truth about his past relationship with Trish.)

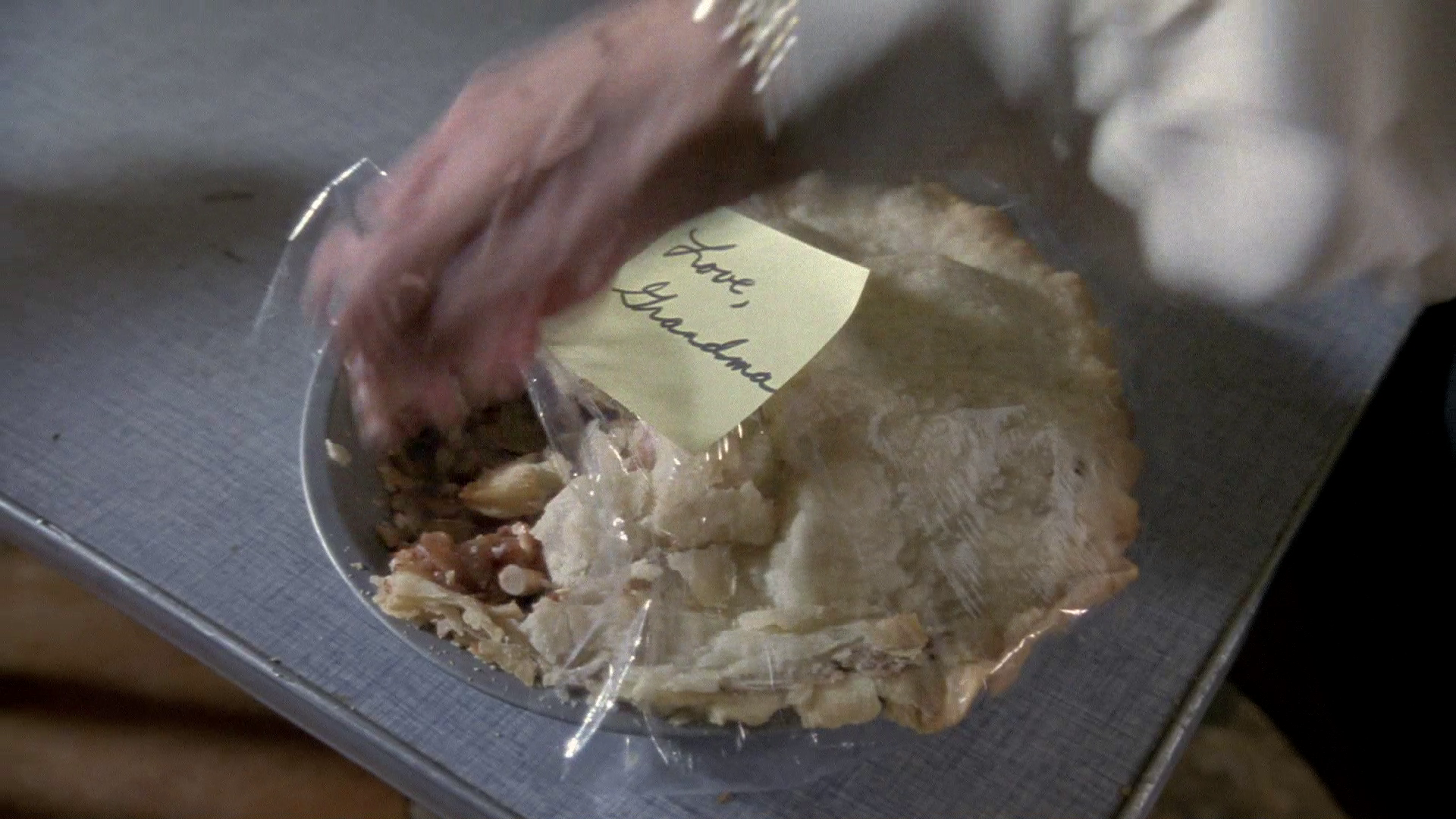

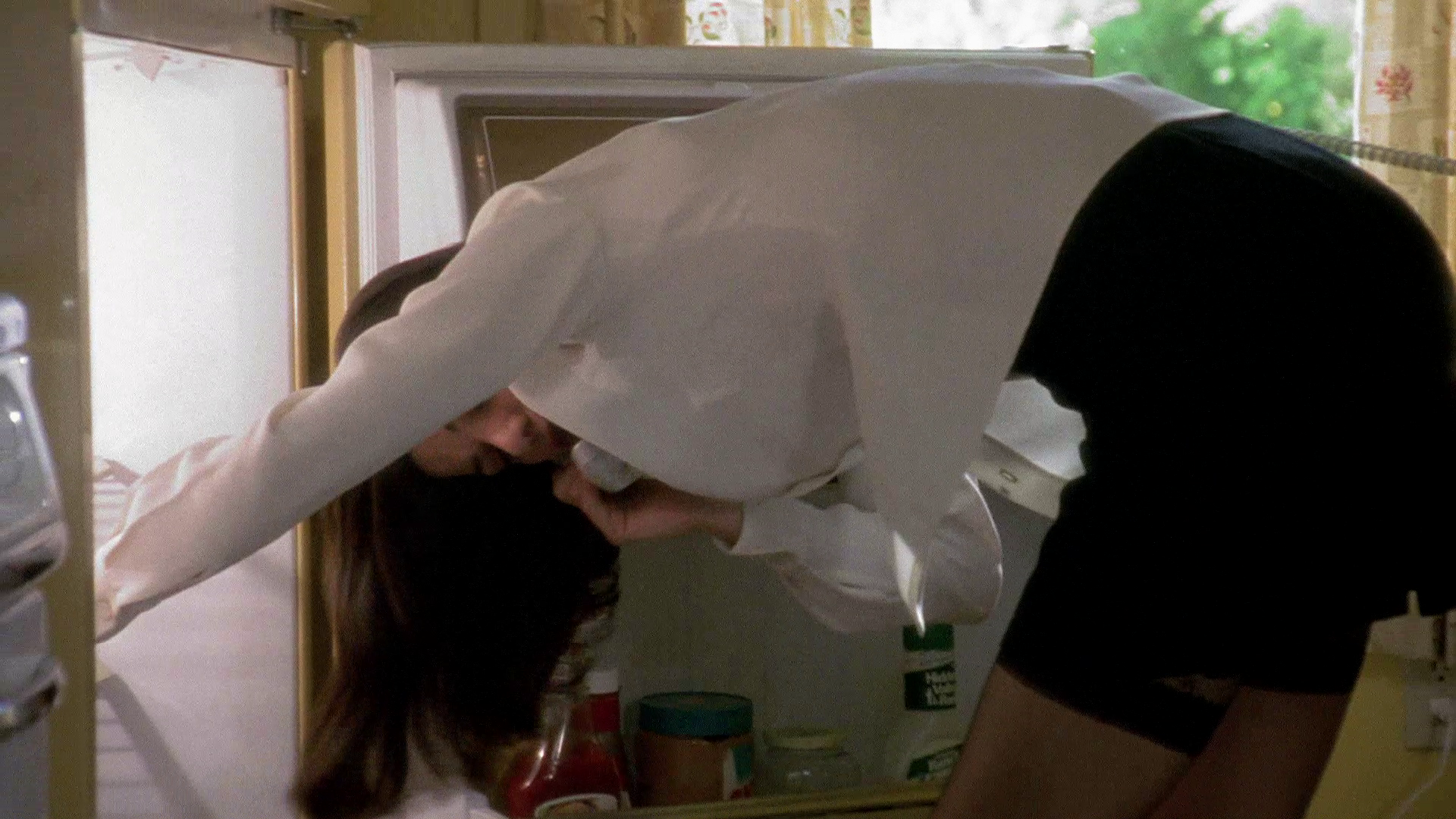

After taking Mike on as what she later calls her ‘designated fuck’, when she wakes in his house the next morning Bridget demonstrates her status as a self-proclaimed ‘total fucking bitch’ by stubbing out a cigarette in a partially-eaten pie in Mike’s kitchen; on the pie is a Post-It Note which reads, simply, ‘Love, Grandma’. (This, incidentally, is the film’s only mention of the family that Mike presumably has in Beston.) Following this, as Bridget buys a newspaper and walks down one of the commercial streets in Beston, she displays her contempt for small town life when she acts visibly annoyed by the fact that everyone who passes her wishes her ‘good morning’.  As the narrative develops, Mike becomes increasingly frustrated by his inability to ‘connect’ with Bridget on an emotional or intellectual level: Bridget sees him purely as an outlet for her animalistic sexual appetite. When she informs him, ‘You’re my designated fuck’, Mike asks, ‘What if I want to be more than your designated fuck?’ ‘I’ll designate someone else’, is Bridget’s reply. Mike finds Bridget’s attitude utterly alien, asking her in disbelief, as they fuck impersonally in a car (Bridget, characteristically, is on top and facing away from Mike), ‘Where are you from?’ ‘A galaxy far, far away’, Bridget laughs. ‘I’m trying to decide if you’re a total bitch or not’, the incredulous Mike declares. ‘A total fucking bitch’, Bridget tells him, pounding the roof of the car with her hands, clearly delighted with this label. When, later, Mike observes, ‘You’re keeping me at arm’s length all the time. I’m starting to feel like a…’, Bridget interrupts him: ‘Sex object? [….] Live it up’. As the narrative develops, Mike becomes increasingly frustrated by his inability to ‘connect’ with Bridget on an emotional or intellectual level: Bridget sees him purely as an outlet for her animalistic sexual appetite. When she informs him, ‘You’re my designated fuck’, Mike asks, ‘What if I want to be more than your designated fuck?’ ‘I’ll designate someone else’, is Bridget’s reply. Mike finds Bridget’s attitude utterly alien, asking her in disbelief, as they fuck impersonally in a car (Bridget, characteristically, is on top and facing away from Mike), ‘Where are you from?’ ‘A galaxy far, far away’, Bridget laughs. ‘I’m trying to decide if you’re a total bitch or not’, the incredulous Mike declares. ‘A total fucking bitch’, Bridget tells him, pounding the roof of the car with her hands, clearly delighted with this label. When, later, Mike observes, ‘You’re keeping me at arm’s length all the time. I’m starting to feel like a…’, Bridget interrupts him: ‘Sex object? [….] Live it up’.

Later, Bridget expresses her plan to use the credit reports of the company for which she and Mike work to identify wealthy married men who are involved in extramarital affairs. Bridget’s plan (or so she tells Mike), a blackly comic parody of her work as a telemarketer, is to approach the wives of these men, telling them of their husbands’ infidelity and offering her and Mike’s services as hired killers – for a fee. The joy in this, Bridget tells a disbelieving Mike (‘This is fun?’), is, as she says, ‘bending the rules, playing with people’s brains’. Of course, Bridget doesn’t go through with any of these murders – but she persuades Mike that she has, showing him a portion of the money she has stolen from Clay and suggesting that she has taken it as payment for the murder of one of the unfaithful husbands she and Mike identified through their research. Mike still expresses his distaste at the idea. ‘Is it the morality of murder that is wrong to you or the personal risk?’, Bridget asks. ‘Murder is wrong’, Mike says, offering a black-and-white interpretation of the situation. Bridget's response to Mike's declaration is to assert ‘Yeah, unless the president says to do it’, a statement which underscores the moral relativism of her worldview and the film's sense of irony (for Bridget, murder is, of course, entirely legitimate if she 'says to do it').

Video

The film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, which would appear to be near-as-dammit to the film’s intended aspect ratio for its theatrical exhibition, if not the ratio of its television premiere. (The HBO premiere of the film was apparently an ‘open matte’ presentation in the 1.33:1 ratio, as was the US DVD release from Artisan; the cinema release was most likely in the ratio of 1.85:1 or thereabouts.) The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, which would appear to be near-as-dammit to the film’s intended aspect ratio for its theatrical exhibition, if not the ratio of its television premiere. (The HBO premiere of the film was apparently an ‘open matte’ presentation in the 1.33:1 ratio, as was the US DVD release from Artisan; the cinema release was most likely in the ratio of 1.85:1 or thereabouts.) The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

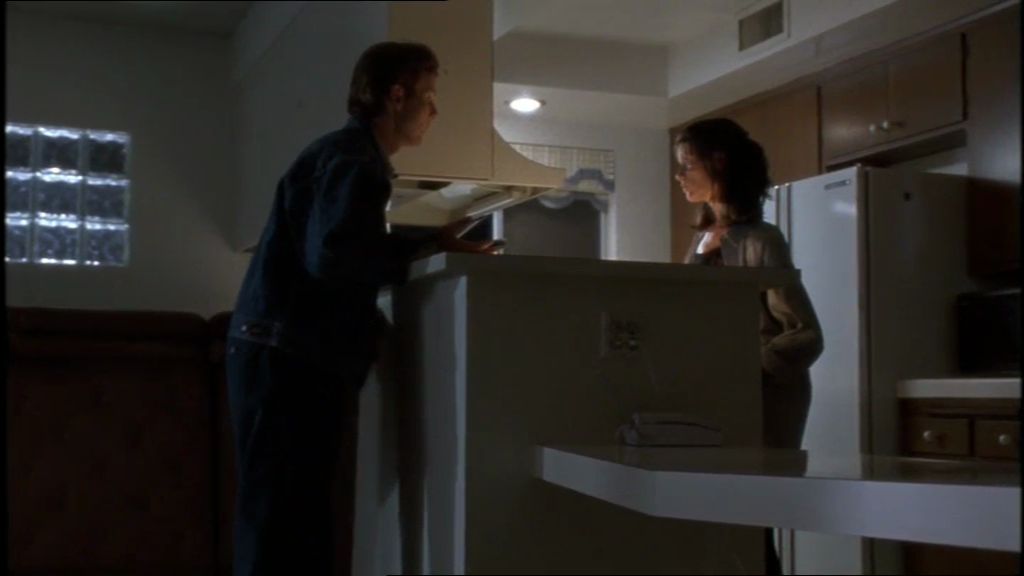

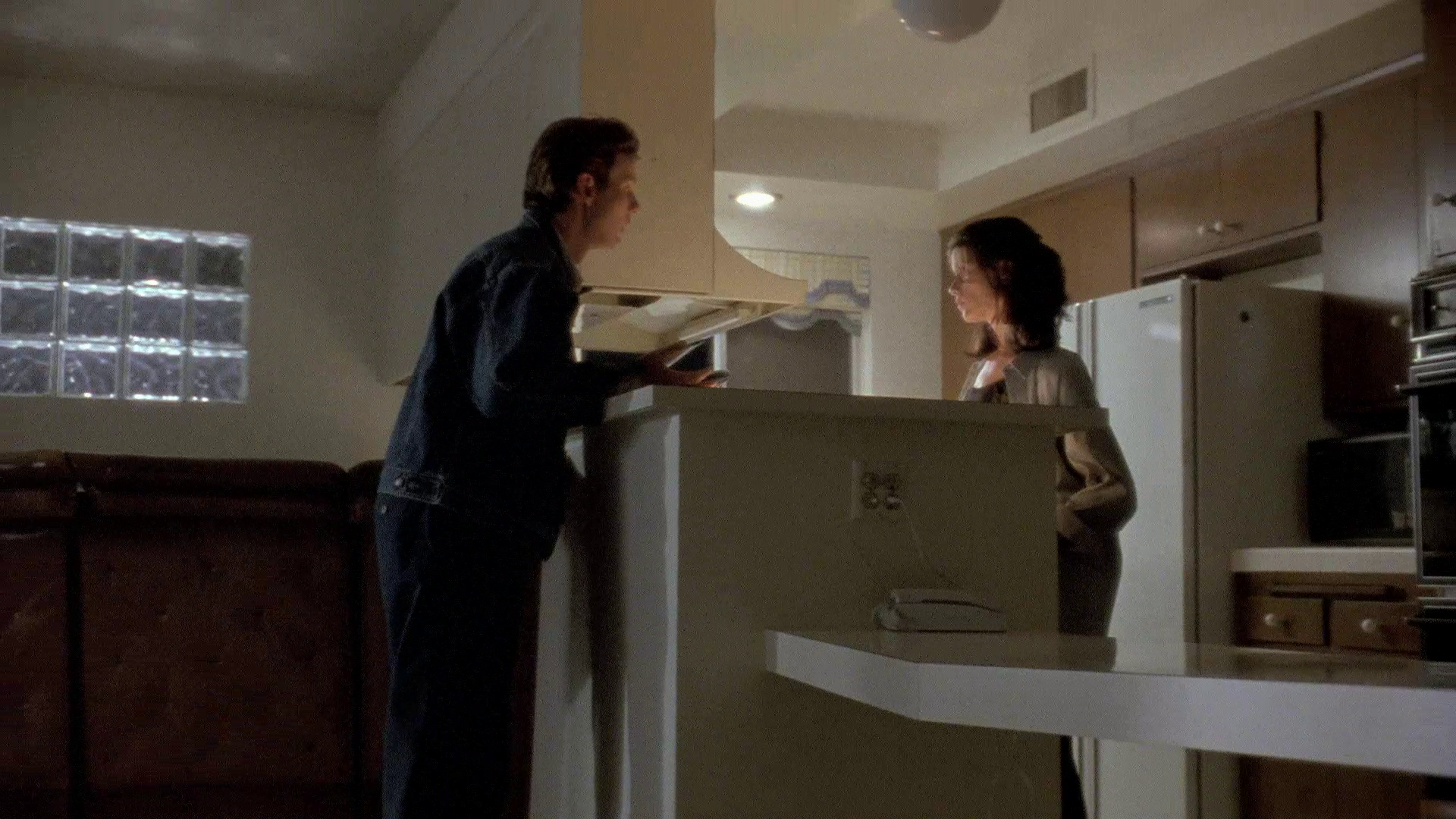

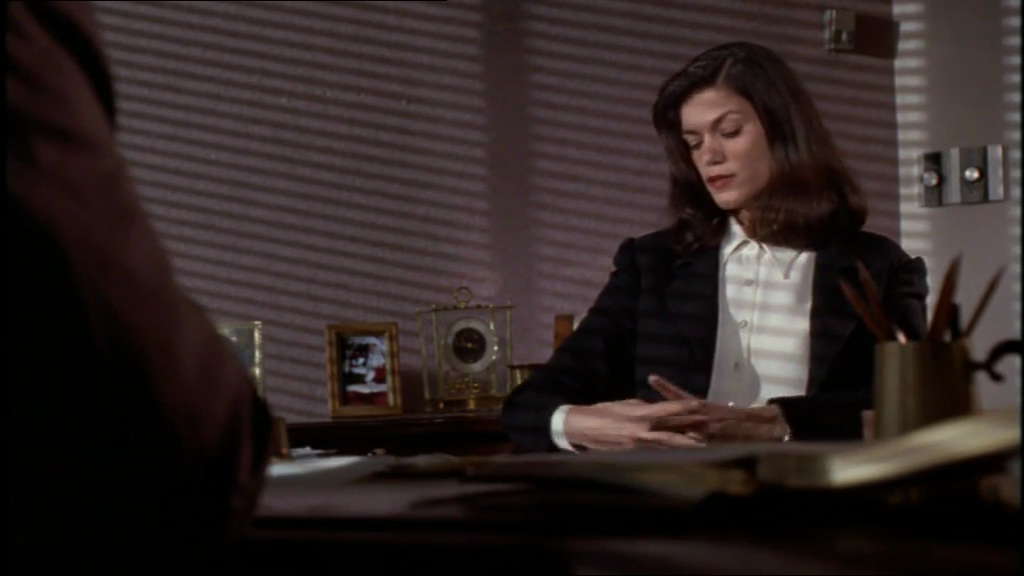

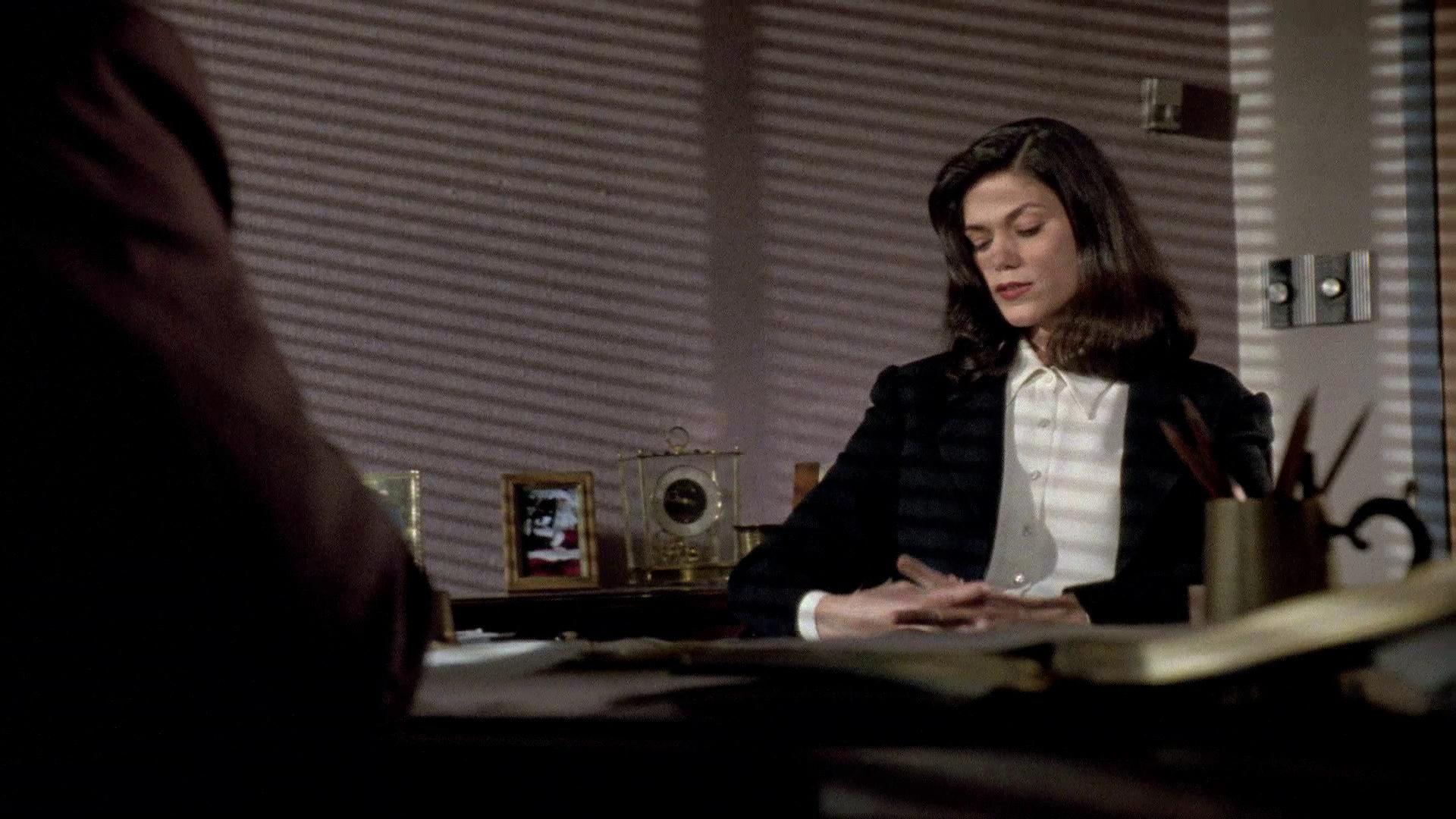

Taking up approximately 19Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, this presentation of The Last Seduction is a mixed bag. Firstly, in comparison with Network’s 2006 special edition DVD, there are some noticeable differences in terms of the framing: this new Blu-ray presentation ‘opens up’ the framing considerably, revealing much more information at the top and left- and right-hand sides of the frame. (See the screengrabs comparing Network’s 2006 DVD with their new Blu-ray release at the bottom of this review.) Contrast levels are noticeably improved over the DVDs (although crushed blacks are still in evidence at certain points), and as can be seen from the screengrabs below, the Blu-ray presentation exhibits a greater level of detail. However, there’s a curious ‘flatness’ to some shots that may or may not be a product of the heavy use of diffuse light in some scenes. Certainly, the master seems dated, and there’s a problem with video noise which is evident throughout the film and which affects some scenes (mostly those shot in low-light, such as the scenes set in Ray’s bar) more noticeably than others. The presentation has the ‘look’ of some of the controversial HD presentations of Italian genre films that have surfaced over the past few years, the problems with which have been suggested to be sourced from the use of a poorly-calibrated CRT scanner: there’s the suggestion of noise reduction within the presentation, with skin texture in some close-ups appearing ‘waxy’, and grain seeming ‘clumpy’ and appearing more like video noise than natural film grain. Whether this is an issue with the scan or perhaps a product of bad compression is, at this juncture, open to debate; but either way, it’s noticeable on even a 32” television, with the problems becoming amplified on larger displays. Certainly, the presentation of the film is better than the DVDs that are available (especially in terms of the framing and contrast), but there’s much room for improvement. The Blu-ray presentation contains the uncut theatrical edit, running 109:54 mins. (Also included, in SD and on the accompanying DVD, is a longer version of the film, said to be Dahl’s preferred cut, which runs for 128:52 PAL.)

Audio

Audio options include a lossy Dolby Digital 5.1 track and a lossless LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Switching between the two, it’s evident that the lossless stereo track offers a much richer experience, with a greater sense of depth to it. This can be hard in the opening titles sequence, in the dynamic range that’s evidenced within the jazzy score (by Joseph Vitarelli) and the cymbal crashes that punctuate it. The lossy Dolby Digital 5.1 track features a more aggressive soundscape but is much more ‘flat’. Because of this, the lossless stereo track is a far better option: it’s cleaner, more dynamic and, because of this, no less immersive than the 5.1 mix. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The release is a two-disc set, containing both a Blu-ray and a DVD. DISC ONE (Blu-ray): Only the first disc, containing the theatrical cut in HD, was available for this review. This disc also includes the following extras. - The film’s trailer (1:45). - A retrospective featurette, ‘The Art of Seduction’ (29:00). This offers some good insight into the film and features new (as of 2006) interviews with Dahl, Barancik and Pullman, and archival interviews with Fiorentino and Berg. - On-set footage (8:30). Here, we are offered a glimpse into the film’s production, via shot-on-video footage that was shot between takes. - A gallery (2:29) of promotional imagery. DISC TWO (DVD): In retail versions of the release, the Blu-ray disc is also packaged with the same second disc that was included in Network’s 2006 special edition DVD release. Although this wasn’t presented for review, I own the 2006 DVD release and can comment on the contents of this second disc. This disc contains: - The extended version of the film, running 128:52 mins (in PAL format). This is a composite, which inserts the deleted footage (from a lesser quality source) into a print of the theatrical cut. This alternate edit of the film is a worthwhile addition, but though the added scenes are interesting to watch, the theatrical cut works just as well. - This extended cut of the film features a commentary by director John Dahl. This is an excellent commentary in which Dahl explores the film’s relationship with classic films noir and talks about his working relationships with both Fiorentino and Bill Pullman. - Deleted scenes with optional commentary (57:19). This feels a little redundant, given that the deleted scenes presented here are included in the extended version of the film. The length of this feature is owing to the fact that the deleted scenes are framed by footage from the final cut of the film, giving an idea of how the deleted footage works in situ. - Alternate ending with optional commentary (10:12). - Episode from HBO’s 1995 series Fallen Angels, directed by John Dahl: ‘Tomorrow I Die’ (28:12). This episode of HBO’s stunning mid-1990s noir series, which is desperately in need of a good DVD release, is directed by Dahl and based on Mickey Spillane’s novel. It features Bill Pullman, Heather Graham and Dan Hedaya in its cast. Whilst not the best installment of Fallen Angels (Steven Soderbergh’s adaptation of David Goodis’ story ‘A Professional Man’ arguably takes that honour), it’s a strong half hour of television and should hopefully provoke more viewers into investigating Fallen Angels (which was shown in some territories under the alternate title of Perfect Crimes).

Overall

The Last Seduction is a superb film, arguably one of the best American films of the 1990s. The film offers a battle of the sexes but also comments just as equally on the conflict between the ‘cosmopolitan’ big city and small town America. Coming after the production of both Kill Me Again and Red Rock West, Dahl shows a confidence in his handling of the noir motifs within the film’s narrative, and the picture also benefits from some superb performances. The photography is less even, with some scenes being expressively lit and shot and others having the ‘flat’ look of a television production – which is hardly surprising, given the low budget. The presentation here is undoubtedly an improvement over the DVDs but compression issues and/or a bad scan have resulted in an image which sometimes loses texture and is dominated by video noise which is more prominent in some scenes (eg, those set in Ray’s bar) than in others. (This should be amply illustrated by the large screen grabs that are included below this review.) The differences in framing between this version and Network’s 2006 DVD are worth noting: this new Blu-ray release opens up the compositions somewhat. In sum, this release of The Last Seduction contains some excellent contextual material but, in terms of the presentation of the main feature, leaves room for improvement. References: Monaco, Paul, 2010: John Dahl and Neo-Noir: Examining Auteurism and Genre. Maryland: Lexington Books Nerroni, Hillary, 2012: The Violent Woman: Femininity, Narrative, and Violence in Contemporary American Cinema. State University of New York Press Williams, Linda Ruth, 2005: The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Indiana University Press

Visual Comparison with Network’s 2006 DVD Release: In each instance, grabs from Network’s 2006 DVD release are on top; grabs from the new Blu-ray are below.

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|