|

|

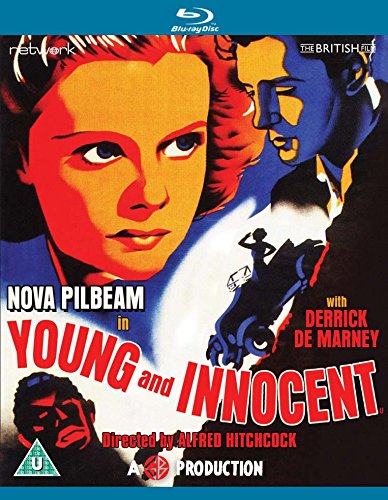

Young and Innocent AKA The Girl Was Young (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st January 2015). |

|

The Film

Young and Innocent (The Girl Was Young) (Alfred Hitchcock, 1937) Young and Innocent (The Girl Was Young) (Alfred Hitchcock, 1937)

The penultimate film in Hitchcock’s sextet of British thrillers, followed by The Lady Vanishes in 1938, Young and Innocent (1937, released in America as The Girl Was Young) tends to be forgotten. The film stands apart from Hitchcock’s other thrillers of this era, and as Charles Barr notes in his introduction to the film on this Blu-ray release, this is largely because Young and Innocent sidesteps the issues of international politics, espionage/spycraft and political terrorism that are at the heart of, for example, The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), Secret Agent (1936), Sabotage (1936) and The Lady Vanishes. Both this film and The Lady Vanishes, the final of Hitchcock’s British thrillers, have a lighter touch – with a heavier focus on comic elements – than the two films which immediately preceded them, Sabotage and Secret Agent, neither of which had been particularly successful in terms of their commercial reception. However, on the other hand Young and Innocent consolidates one of the key themes of Hitchcock’s later Hollywood films, that of the ‘wrong man’ who is pursued by the authorities for a crime he did not commit. The film also features the first use of a virtuoso long take that recurs with similar staging in both Notorious (1946) and Marnie (1964); in Young and Innocent, this shot carries our attention from an overhead perspective of the crowded ballroom in which the film’s climax is set, to a close-up of the twitching eye of the film’s real villain. The film opens with conflict. A male voice is heard on the soundtrack, sharply declaring, ‘Christine!’ Subsequently, faces are shown in tense close-ups. The faces belong to a man and a woman, Christine Clay (Pamela Carme) and her husband Guy (George Curzon). Guy tells Christine, ‘You’re a liar and a cheat’. Christine slaps Guy; Guy’s reaction is to leave silently.  The next day, a woman’s body is washed up on a beach. It’s Christine. Robert Tisdall (Derrick De Marney) discovers her corpse and realises she has been strangled with a belt. Two women arrive on the scene as Robert flees the beach, apparently to get help. The women’s testimony, given to the police shortly after, suggests that Robert is the culprit and that he was running away after murdering Christine. The next day, a woman’s body is washed up on a beach. It’s Christine. Robert Tisdall (Derrick De Marney) discovers her corpse and realises she has been strangled with a belt. Two women arrive on the scene as Robert flees the beach, apparently to get help. The women’s testimony, given to the police shortly after, suggests that Robert is the culprit and that he was running away after murdering Christine.

The police suspect Robert, and discover that he was once Christine’s lover. Furthermore, it seems that in her will, Christine has left Robert twelve hundred pounds. Discovering that he is the prime suspect in the murder of Christine, Robert passes out and is brought to by Erica Burgoyne (Nova Pilbeam), the daughter of the Chief Constable (Percy Marmont). During the trial, Robert manages to escape and flees to the countryside. He encounters Erica and commandeers her car. She helps him to escape, reluctantly at first (‘I can laugh because I’m innocent’, Robert tells her, ‘You don’t believe that, do you? I wish you did’) but gradually comes to believe in Robert’s innocence. The prosecution’s case apparently hinges on the belt that was used to strangle Christine, which they claim came from Robert’s coat – a coat that Robert lost. Investigating this lead, Erica and Robert discover that Robert’s coat was stolen and is in the hands of a tramp and china mender known as ‘Old Will’. After a stop-off at the home of Erica’s aunt and uncle, who are throwing a birthday party for Erica’s young cousin, Erica and Robert manage to track down Old Will, who tells them that the belt was missing from the coat when it was given to him. Old Will also tells the couple that he can identify the man who gave him the coat: this man, who Erica and Robert deduce to be the murderer of Christine, has a distinctive facial tic.  Young and Innocent was adapted from Josephine Tey’s 1936 novel A Shilling for Candles. The film’s script was written by Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood and Anthony Armstrong, with uncredited contributions from Hitchcock’s wife, Alma Reville. This would be the final British film on which Hitchcock collaborated with Bennett, whose departure for Hollywood was compensated for by the hiring of Greenwood, Armstrong and Alma Reville to finish the script (Adair, 2002: 57). In interview, Bennett himself asserted that with regards Young and Innocent he contributed very little to the script, only ‘the construction of the scenes; working out the scenes’ (quoted in McGilligan, 1986: 27). (Bennett and Hitchcock collaborated for the first time on Blackmail, 1929, which was based on Bennett’s play; Bennett contributed to all but one of Hitchcock’s six British thrillers of the 1930s, the odd film out being the final film of the cycle, The Lady Vanishes.) Hitchcock and Bennett would, of course, reunite in Hollywood. Young and Innocent was adapted from Josephine Tey’s 1936 novel A Shilling for Candles. The film’s script was written by Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood and Anthony Armstrong, with uncredited contributions from Hitchcock’s wife, Alma Reville. This would be the final British film on which Hitchcock collaborated with Bennett, whose departure for Hollywood was compensated for by the hiring of Greenwood, Armstrong and Alma Reville to finish the script (Adair, 2002: 57). In interview, Bennett himself asserted that with regards Young and Innocent he contributed very little to the script, only ‘the construction of the scenes; working out the scenes’ (quoted in McGilligan, 1986: 27). (Bennett and Hitchcock collaborated for the first time on Blackmail, 1929, which was based on Bennett’s play; Bennett contributed to all but one of Hitchcock’s six British thrillers of the 1930s, the odd film out being the final film of the cycle, The Lady Vanishes.) Hitchcock and Bennett would, of course, reunite in Hollywood.

John Orr has suggested that Young and Innocent, with Erica and Robert’s flight from the police and their race to discover the identity of the real murderer of Christine, is a ‘lackadaisical’ reworking of the ‘flight-narrative’ that Hitchcock had developed in his film adaptation of John Buchan’s The 39 Steps ‘but without the spy element’ (Orr, 2005: 80; Adair, op cit.: 57). Interviewed by Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock himself described Young and Innocent as ‘an attempt to do a chase narrative with very young people involved’ (quoted in Truffaut, 1983: 111). Nova Pilbeam, the film’s female lead, was 18 at the time the film was made, and Young and Innocent was intended to be her ‘first adult role’ (she had already acted for Hitchcock, at the age of 14, as the imperiled daughter in The Man Who Knew Too Much) (Chandler, 2005: np). Hitchcock apparently considered using Pilbeam in the role eventually filled by Margaret Lockwood in The Lady Vanishes. (At one point, Hitchcock also intended to cast Pilbeam in Perjury, based on Marcel Achard’s short story ‘False Witness’: an unrealised project which was announced towards the end of 1937 and would have been Hitchcock’s next film after Young and Innocent.)  Robert’s innocence is never in doubt, and the film’s approach to its material is light and largely comic. As Robert and Erica flee the police, for example, they stop at a rural petrol station. Not knowing that the couple he is serving are the pair who are being sought by the police, the owner tells Erica and Robert about the escape that’s been reported in the wireless. A police car has already stopped at the petrol station for a fill-up, the owner tells Erica and Robert, adding, ‘If you see that feller [the escapee], you might tell him to keep escaping: it’s good for business’. During the film’s climax, set during a ball at the Grand Hotel, much comedy arises from the juxtaposition of the grand surroundings and the immaculate dress of those attending the event, and Old Will the china mender, who Erica has brought with her owing to the fact that he can identify the murderer. Old Will wears an ill-fitting suit which establishes his out-of-placeness visually, and when he is approached by a waiter, he asks for two cups of tea. ‘India or China, sir?’, the waiter asks him. Old Will, confused, responds, ‘No, tea’. Robert’s innocence is never in doubt, and the film’s approach to its material is light and largely comic. As Robert and Erica flee the police, for example, they stop at a rural petrol station. Not knowing that the couple he is serving are the pair who are being sought by the police, the owner tells Erica and Robert about the escape that’s been reported in the wireless. A police car has already stopped at the petrol station for a fill-up, the owner tells Erica and Robert, adding, ‘If you see that feller [the escapee], you might tell him to keep escaping: it’s good for business’. During the film’s climax, set during a ball at the Grand Hotel, much comedy arises from the juxtaposition of the grand surroundings and the immaculate dress of those attending the event, and Old Will the china mender, who Erica has brought with her owing to the fact that he can identify the murderer. Old Will wears an ill-fitting suit which establishes his out-of-placeness visually, and when he is approached by a waiter, he asks for two cups of tea. ‘India or China, sir?’, the waiter asks him. Old Will, confused, responds, ‘No, tea’.

Comedy is also built around the authority figures within the film. Followin his arrest, Robert is given an incompetent and ill-prepared barrister who simply declares that ‘A case like this is most exciting for us all’. For the most part, the police seem no less incompetent. In their pursuit of Robert, after he has escaped from custody, the police commandeer a pig farmer’s horsedrawn cart. ‘Can’t you go any faster?’, one of the policemen complains to the farmer. ‘Pigs don’t like it’, the farmer replies tersely. ‘We’re on a job’, the policeman asserts. ‘Pigs is my job’, the farmer responds.  During their flight from the police and their struggle to unmask Christine’s killer, in an extended sequence (trimmed in the version of the film released to cinemas in America) Robert and Erica stop off at the home of Erica’s aunt and uncle, where the children at a birthday party being held for Erica’s young cousin are playing a game of Blind Man’s Bluff. The child’s party and game remind us, Thomas M Leitch has said, of the youth of the film’s two leads (1991: 89). The game itself acts as a metaphor for the police’s attempts to capture Robert, and Robert and Erica’s attempts to evade the police. (The game makes a reappearance in Hitchcock’s later film The Birds, 1963, where alongside some more pointed visual metaphors – for example, the pecking out of eyes by the attacking birds – it once again points to themes of sight and perception.) The party sequence also offers contrasting representations of authority figures, with Erica’s aunt presiding over the children’s party with authoritarian relish, whilst her uncle (who incidentally allows Robert and Erica to escape after blindfolding Erica’s aunt as part of the game) takes an active role in the games and ensures the children have fun. The sequence certainly halts or sidetracks the chase narrative (which is most likely the reason for its omission in the American cut of the film), but underscores some of the film’s themes. The motif of blindness introduced in the game of Blind Man’s Bluff is, Maurice Yacowar has noted, placed in juxtaposition with the camera’s ‘supreme power to see’ during the bravura shot within the climax that, in a single take, takes us from an overhead shot of the ballroom to a close-up of the twitching eye of the real murderer (2010: 182). During their flight from the police and their struggle to unmask Christine’s killer, in an extended sequence (trimmed in the version of the film released to cinemas in America) Robert and Erica stop off at the home of Erica’s aunt and uncle, where the children at a birthday party being held for Erica’s young cousin are playing a game of Blind Man’s Bluff. The child’s party and game remind us, Thomas M Leitch has said, of the youth of the film’s two leads (1991: 89). The game itself acts as a metaphor for the police’s attempts to capture Robert, and Robert and Erica’s attempts to evade the police. (The game makes a reappearance in Hitchcock’s later film The Birds, 1963, where alongside some more pointed visual metaphors – for example, the pecking out of eyes by the attacking birds – it once again points to themes of sight and perception.) The party sequence also offers contrasting representations of authority figures, with Erica’s aunt presiding over the children’s party with authoritarian relish, whilst her uncle (who incidentally allows Robert and Erica to escape after blindfolding Erica’s aunt as part of the game) takes an active role in the games and ensures the children have fun. The sequence certainly halts or sidetracks the chase narrative (which is most likely the reason for its omission in the American cut of the film), but underscores some of the film’s themes. The motif of blindness introduced in the game of Blind Man’s Bluff is, Maurice Yacowar has noted, placed in juxtaposition with the camera’s ‘supreme power to see’ during the bravura shot within the climax that, in a single take, takes us from an overhead shot of the ballroom to a close-up of the twitching eye of the real murderer (2010: 182).

As presented on this disc, the film is uncut and runs for 82:55 mins.

Video

The film, taking up approximately 16Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. It’s an admirable presentation of the film. The film exhibits more damage than Network’s HD presentations of The Lady Vanishes and The Man Who Knew Too Much, with some scratches and debris evident throughout the picture. There are some soft shots that have an out-of-focus look which doesn’t appear to be a product of the original photography (see the large image below) and may point to damage to the film’s negative. However, regardless of this damage the presentation is clear and organic, with a lovely sense of filmlike depth to it and a natural grain structure that seems handled well within the encode, even given the small file size of the main feature.

NB. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented with a lossless LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clear and audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes, as contextual material: - an introduction by critic and film historian Charles Barr (3:34). This is carried over from Network’s 2008 DVD release of the film. Barr talks about Young and Innocent’s relationship with Hitchcock’s other British thrillers and offers an interesting discussion of the significance of Hitchcock’s cameo in this film. - ‘The Carlton Film Collection - A Profile of Hitchcock: The Early Years’ featurette (24:02). This 2000 piece, discussing Hitchcock’s pre-Hollywood films, features ample archive footage and interviews, and was originally included on Carlton’s DVD release of The 39 Steps. - a gallery (1:12).

Overall

Young and Innocent seems slight when placed against Hitchcock’s other British thrillers of the period, largely because of the ways in which it sidesteps issues of politics, and it’s probably for this reason that it’s often neglected and is more little-seen than, say, The 39 Steps or The Lady Vanishes. However, it’s a fun, engaging film that, on reflection, contains some elements that consolidate the themes of Hitchcock’s work and, in particular, looks forwards to some of the elements within Hitchcock’s Hollywood films. Young and Innocent seems slight when placed against Hitchcock’s other British thrillers of the period, largely because of the ways in which it sidesteps issues of politics, and it’s probably for this reason that it’s often neglected and is more little-seen than, say, The 39 Steps or The Lady Vanishes. However, it’s a fun, engaging film that, on reflection, contains some elements that consolidate the themes of Hitchcock’s work and, in particular, looks forwards to some of the elements within Hitchcock’s Hollywood films.

The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is pleasing, and there is some good contextual material. As with Network’s other Blu-ray releases of Hitchcock’s British thrillers (The Lady Vanishes and The Man Who Knew Too Much), Young and Innocent is definitely a worthwhile purchase for fans of both Hitchcock and, more generally, British cinema.  References: Adair, Gene, 2002: Alfred Hitchcock: Filming Our Fears. Oxford University Press Chandler, Charlotte, 2005: It’s Only a Movie: Alfred Hitchcock, a Personal Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster Leitch, Thomas M, 1991: Find the Director and Other Hitchcock Games. University of Georgia Press McGilligan, Pat, 1986: ‘Charles Bennett: First-Class Constructionist’. In: McGilligan, Pat (ed), 1986: Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age. University of California Press: 17-48 Orr, John, 2005: Hitchcock and 20th Century Cinema. London: Wallflower Press Truffaut, Francois, 1983: Truffaut/Hitchcock. London: Simon & Schuster Yacowar, Maurice, 2010: Hitchcock’s British Films. Wayne State University Press (Second Edition) This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|