|

|

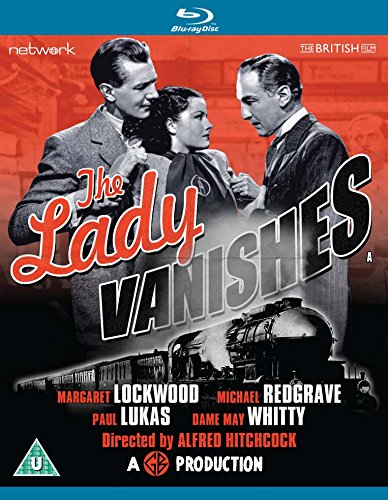

Lady Vanishes (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th February 2015). |

|

The Film

The Lady Vanishes (Alfred Hitchcock, 1938) The Lady Vanishes (Alfred Hitchcock, 1938)

The final film in Hitchcock’s sextet of British thrillers, The Lady Vanishes (1938) was the first of this group of films whose script didn’t feature contributions from Charles Bennett, who by this point in his career had moved to Hollywood. The film was preceded by The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), Sabotage (1936), Secret Agent (1936) and Young & Innocent (1937). Bennett had scripted most of these, though he didn’t contribute to the dialogue of the film that immediately preceded The Lady Vanishes, Young and Innocent, only providing the film with ‘the construction of the scenes; working out the scenes’ (Bennett, quoted in McGilligan, 1986: 27). Young and Innocent deviated somewhat from the template established in the first four films of this group, all of which featured some focus on espionage and international politics. However, with The Lady Vanishes, written by Sidney Launder and Frank Gilliat, Hitchcock returned to the themes of spycraft and contemporary political tensions. Interestingly, given this, the script for The Lady Vanishes wasn’t written for Hitchcock but was originally intended for another director, Roy William Neill, and production began in 1936 but was abandoned after Neill fractured his ankle on set and, investigating this accident, police officials became unimpressed with the film’s script’s representation of their country (see Adair, 2002: 59). The only significant change Hitchcock requested upon taking over the project was a rewriting of the opening and closing sequences. (Hitchcock’s willingness to take the credit for The Lady Vanishes reputedly resulted in sour grapes between Hitchcock and the team of Launder and Gilliat.)  The narrative of The Lady Vanishes takes place in the fictional country of Bandrika, where a group of tourists – including Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood), who is due to be married on her return to England; ethno-musician Gilbert (Michael Redgrave); and Chalders and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne) – are forced to stay the night at the The narrative of The Lady Vanishes takes place in the fictional country of Bandrika, where a group of tourists – including Iris Henderson (Margaret Lockwood), who is due to be married on her return to England; ethno-musician Gilbert (Michael Redgrave); and Chalders and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne) – are forced to stay the night at the

Gasthof Petrus inn, following an avalanche which blocks the train line. During the evening, Iris comes into conflict with Gilbert owing to his compulsion to loudly practise music in his room, which is directly above hers. The inn is already full to the point of overflowing, and cruelly Iris demands that Gilbert be expelled from his room, only to find her desire for peace frustrated when Gilbert, realising that Iris is responsible for his expulsion, takes up residence in her room instead. During her stay in the inn, Iris strikes up a friendship with Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty), an elderly lady who is returning to England having spent six years working as ‘a governess and a music teacher’ in Bandrika. When they leave the inn and depart on the train, after the line has been cleared, Iris and Miss Froy share a compartment. However, Iris falls asleep and when she awakens, discovers that Miss Froy has disappeared. The other travellers in their shared compartment insist that ‘There has been no English lady here’. Iris attempts to find out what has happened to Miss Froy but discovers resistance throughout the train: Charters and Caldicott don’t want any delays on their journey home to see the Test Match, and realise that admitting they have seen Miss Froy would result in the train being stopped and an investigation begun; and Iris is also refused help by another English passenger, a man who is travelling with his mistress and doesn’t want their affair to become public knowledge. Meanwhile, other passengers on the train refuse to acknowledge Miss Froy’s existence, suggesting that Iris may have imagined Miss Froy and her disappearance after suffering a blow to the head immediately before boarding the train.  However, Iris manages to persuade Gilbert to help her. Working together, they discover a conspiracy to abduct Miss Froy, who is in fact an English spy who was on her way to deliver an important message to the Foreign Office. Many of the foreign travellers encountered by Iris are involved in the conspiracy to ‘do away’ with Miss Froy. Working with Gilbert, Iris manages to free Miss Froy, resulting in the train being diverted onto a branch line where it is beset by foreign soldiers; there, Iris, Gilbert and the initially reluctant Charters and Caldicott must fend off the attacking forces, protect Miss Froy and enact their escape. However, Iris manages to persuade Gilbert to help her. Working together, they discover a conspiracy to abduct Miss Froy, who is in fact an English spy who was on her way to deliver an important message to the Foreign Office. Many of the foreign travellers encountered by Iris are involved in the conspiracy to ‘do away’ with Miss Froy. Working with Gilbert, Iris manages to free Miss Froy, resulting in the train being diverted onto a branch line where it is beset by foreign soldiers; there, Iris, Gilbert and the initially reluctant Charters and Caldicott must fend off the attacking forces, protect Miss Froy and enact their escape.

Iris’ struggle to convince the other passengers on the train of Miss Froy’s disappearance (and, for that matter, her existence) underscores the element of paranoid fantasy that exists within many of Hitchcock’s films: for example, L B Jefferies’ (James Stewart) struggle in Rear Window (1954) to persuade Lisa (Grace Kelly), Stella (Thelma Ritter) and the authorities that the man in the apartment opposite his (Raymond Burr) has murdered his wife. In both Rear Window and The Lady Vanishes, the protagonists’ attempts to highlight a conspiracy are dismissed by other characters as delusions. David Sterritt has suggested, in its exploration of Iris’ attempts to prove that her memories of Miss Froy are more than mere delusions, The Lady Vanishes can be grouped with The 39 Steps, Spellbound (1945) and Marnie (1964) as a film that highlights ‘his [Hitchcock's] belief that memory can defend against the future by reconjuring the past’ (2002: 312). The Lady Vanishes offers an oblique commentary on the then-state of Europe that was foregrounded in the 1979 remake (directed by Anthony Page), which translated the narrative from the fictional country of Bandrikan to pre-war Nazi Germany. In Hitchcock’s film, Jeffrey Richards argues, the Bandrikan police who lay siege to the train during the climax ‘are clearly intended to be seen as the Gestapo’ (Richards, 1997: 86). Produced after the start of the Second World War, Carol Reed’s later Night Train to Munich (1940), which also features Charters and Caldicott (and, like The Lady Vanishes, stars Margaret Lockwood) offers a more direct examination of ‘Germans as Nazis, whereas The Lady Vanishes merely hints at a sinister regime’ (Wapshott, quoted in Mavis, 2011: np). Within this context, the various English characters’ refusal of Iris’ request for help in the search for the missing Miss Froy – largely out of self-interest and an abiding concern with their own agendas (Charters and Caldicott want to get back home in time for the Test Match; the philandering lawyer wishes to keep secret the affair he’s been conducting behind the back of his wife) – seems like a commentary on Britain’s 1930s policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. An interesting point of contrast with Hitchcock’s film, Graham Greene’s 1932 novel Stamboul Train features a similar train setting and offers a more direct examination of what was taking place in Europe at the time that the novel was written, with Greene referring directly to the countries through which the train passes, offering commentary on them.  The characters of Charters and Caldicott, the two cricked-obsessed Englishmen performed by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne, proved popular with audiences and would appear in Night Train to Munich (Carol Reed, 1940) and Millions Like Us (Gilliat & Launder, 1943), as well as a couple of BBC radio serials. Radford and Wayne played Charters and Caldicott-type characters in a good number of other films. Shortly after Charters and Caldicott are introduced here, they are shown in a conversations about ‘our communications being cut off in a time of crisis’. They appear to be politically engaged but this is undercut almost immediately, when it is revealed that they are in fact discussing their difficulty in discovering how England are doing in the Test Match. Charters and Caldicott’s attitude towards the locals represents the parochial stereotype of Englishness. At the inn, they see the manager giving preferential treatment to three pretty young women. ‘Meanwhile, we have to stand here, cooling our heels, eh? Confounded impudence’, Charters says. ‘Oh, third rate country. What do you expect?’, Caldicott responds. The manager offers Charters and Caldicott the maid’s room. ‘You can’t expect to put the two of us up in the maid’s room’, Charters complains. ‘Oh, don’t get excited! I’ll remove the maid out’, the manager tells them before Charters and Caldicott raise their eyebrows at the manager’s suggestion that the maid, Anna, ‘remove her wardrobe’. At the dinner table that evening, the waiter repeatedly attempts to inform Charters and Caldicott that there is no food left. ‘These people have a passion for repeating themselves’, Charters comments before, once comprehending the waiter’s message, asserting, ‘No food! They expect us to share a blasted dog box with a servant girl on an empty stomach? Is that hospitality? Is that organisation? What a country! I don’t wonder they have revolutions’. The characters of Charters and Caldicott, the two cricked-obsessed Englishmen performed by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne, proved popular with audiences and would appear in Night Train to Munich (Carol Reed, 1940) and Millions Like Us (Gilliat & Launder, 1943), as well as a couple of BBC radio serials. Radford and Wayne played Charters and Caldicott-type characters in a good number of other films. Shortly after Charters and Caldicott are introduced here, they are shown in a conversations about ‘our communications being cut off in a time of crisis’. They appear to be politically engaged but this is undercut almost immediately, when it is revealed that they are in fact discussing their difficulty in discovering how England are doing in the Test Match. Charters and Caldicott’s attitude towards the locals represents the parochial stereotype of Englishness. At the inn, they see the manager giving preferential treatment to three pretty young women. ‘Meanwhile, we have to stand here, cooling our heels, eh? Confounded impudence’, Charters says. ‘Oh, third rate country. What do you expect?’, Caldicott responds. The manager offers Charters and Caldicott the maid’s room. ‘You can’t expect to put the two of us up in the maid’s room’, Charters complains. ‘Oh, don’t get excited! I’ll remove the maid out’, the manager tells them before Charters and Caldicott raise their eyebrows at the manager’s suggestion that the maid, Anna, ‘remove her wardrobe’. At the dinner table that evening, the waiter repeatedly attempts to inform Charters and Caldicott that there is no food left. ‘These people have a passion for repeating themselves’, Charters comments before, once comprehending the waiter’s message, asserting, ‘No food! They expect us to share a blasted dog box with a servant girl on an empty stomach? Is that hospitality? Is that organisation? What a country! I don’t wonder they have revolutions’.

By contrast with Charters and Caldicott, Miss Froy and Gilbert show an interest in the culture of Bandrikan: Gilbert, an ethnomusicologist, is intent on studying the music of the country; whilst Miss Froy, ostensible a governess and music teacher, has worked in the country for six years. ‘Everyone sings here’, Miss Froy observes, ‘The people are just like happy children, with laughter on their lips and music in their hearts’. ‘It’s not reflected in their politics, you know’, Charters responds, cynically. ‘I never think you should judge any country by its politics’, Miss Froy tells him, ‘After all, we English are quite honest by nature, aren’t we?’ Gilbert, who at least in the early stages proves to be the only aide in Iris’ quest to find Miss Froy, comments on the other English passengers’ lack of engagement, suggesting that their passivity is ‘just British diplomacy […] “Never climb a fence if you can sit on it”. That’s an old Foreign Office proverb'. The short tune which Miss Froy must carry to the Foreign Office, and in which is embedded a secret message, is a strong example of Hitchcock’s fascination with the ‘MacGuffin’: it ‘is simply the device that gets the action going, especially in a spy story or thriller’ (Gottlieb, 2002: 48). The ‘exact details’ of this narrative device ‘are inconsequential’ (ibid.). Hitchcock often pointed to Rudyard Kipling’s work as the origin for his approach to the MacGuffin, but Sidney Gottlieb argues that Hitchcock may as well have referenced Fritz Lang’s films: Lang ‘was not primarily interested in the specifics of the treaty bandied about in Spies [Spione, 1928] or the particulars behind Dr. Mabuse’s blackmail and extortions: his real effort was in dramatizing the dynamics of power, tension, and suspense, and sketching a landscape of mystery that enveloped the protagonists and the audience alike’ (ibid.). Likewise, in Hitchcock’s films the MacGuffins (for example, Miss Froy’s secret message carried in the tune) ‘are no more than rocks thrown into the water that quickly sink to the bottom: Hitchcock’s interest, like Lang’s, is always in the ripples and reverberations’ (ibid.). The film is uncut and runs for 95:38 mins.

Video

Presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, the film is here in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The presentation is remarkably ‘clean’ and free of debris and damage. Film grain looks natural, although the file size is admittedly small and the encode could be stronger; fortunately, there is no evidence of overzealous noise reduction or sharpening. The contrast levels are solid and serve the monochrome photography well, with strong midtones. This is arguably the best presentation of the three Hitchcock films that Network have released on Blu-ray recently. (The other two films are Young and Innocent, reviewed here, and The Man Who Knew Too Much, reviewed here.) NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clear throughout, and is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The disc includes an introduction by critic Charles Barr (4:02). Barr introduces the film wearing the tie of the Marylebone Cricket Club, ‘in honour of two of the most memorable characters in The Lady Vanishes’: Charters and Caldicott. (Charters and Caldicott, Barr tells us, were in the original script directly linked to the Marylebone Cricket Club but this reference was cut out of the film owing to fears that American audiences wouldn’t understand it.) Their obsessive desire to get home to see the Test March ‘makes for some fine comic moments but it also becomes seriously symptomatic of a certain kind of wilted, upper-class British blindness to the menace of fascism. [They] wilfully and selfishly ignore the nasty business that’s going on around them [….] until it’s almost too late’. Barr also discusses the fact that the film is a rare example of Hitchcock taking over a project originally intended for another director, and suggests that the writers, Launder and Gilliat, share authorship of the film with Hitchcock. Also included is the film’s trailer (1:57) and a stills gallery (4:41).

Overall

The Lady Vanishes is a superb film, one of Hitchcock’s best English thrillers. (Hitchcock’s next and last British film, Jamaica Inn (1939), was sadly a step down from The Lady Vanishes.) The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray release is very pleasing, though the encode is a little ‘stingy’. The disc certainly offers a vast improvement over the DVDs that have been available. Along with Network’s other Blu-ray releases of Hitchcock’s British thrillers, for Hitchcock fans and for fans of British cinema, this Blu-ray release is most definitely a worthwhile purchase. The Lady Vanishes is a superb film, one of Hitchcock’s best English thrillers. (Hitchcock’s next and last British film, Jamaica Inn (1939), was sadly a step down from The Lady Vanishes.) The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray release is very pleasing, though the encode is a little ‘stingy’. The disc certainly offers a vast improvement over the DVDs that have been available. Along with Network’s other Blu-ray releases of Hitchcock’s British thrillers, for Hitchcock fans and for fans of British cinema, this Blu-ray release is most definitely a worthwhile purchase.

References: Adair, Gene, 2002: Alfred Hitchcock: Filming Our Fears. Oxford University Press Gottlieb, Sidney, 2002: ‘Early Hitchcock: The German Influence’. In: Gottlieb, Sidney & Brookhouse, Christopher (eds), 2002: Framing Hitchcock: Selected Essays from the Hitchcock Annual. Wayne State University: 35-58 Mavis, Paul, 2011: The Espionage Filmography. London: McFarland McGilligan, Pat, 1986: ‘Charles Bennett: First-Class Constructionist’. In: McGilligan, Pat (ed), 1986: Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age. University of California Press: 17-48 Richards, Jeffrey, 1997: Films and British National Identity: From Dickens to ‘Dad’s Army’. Manchester University Press Samuels, Robert, 1998: Hitchcock’s Bi-Textuality: Lacan, Feminisms, and Queer Theory. State University of New York Press Sterritt, David, 2002: ‘Alfred Hitchcock: Registrar of Births and Deaths’. In: Gottlieb, Sidney & Brookhouse, Christopher (eds), 2002: Framing Hitchcock: Selected Essays from the Hitchcock Annual. Wayne State University: 310-324 This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|