|

|

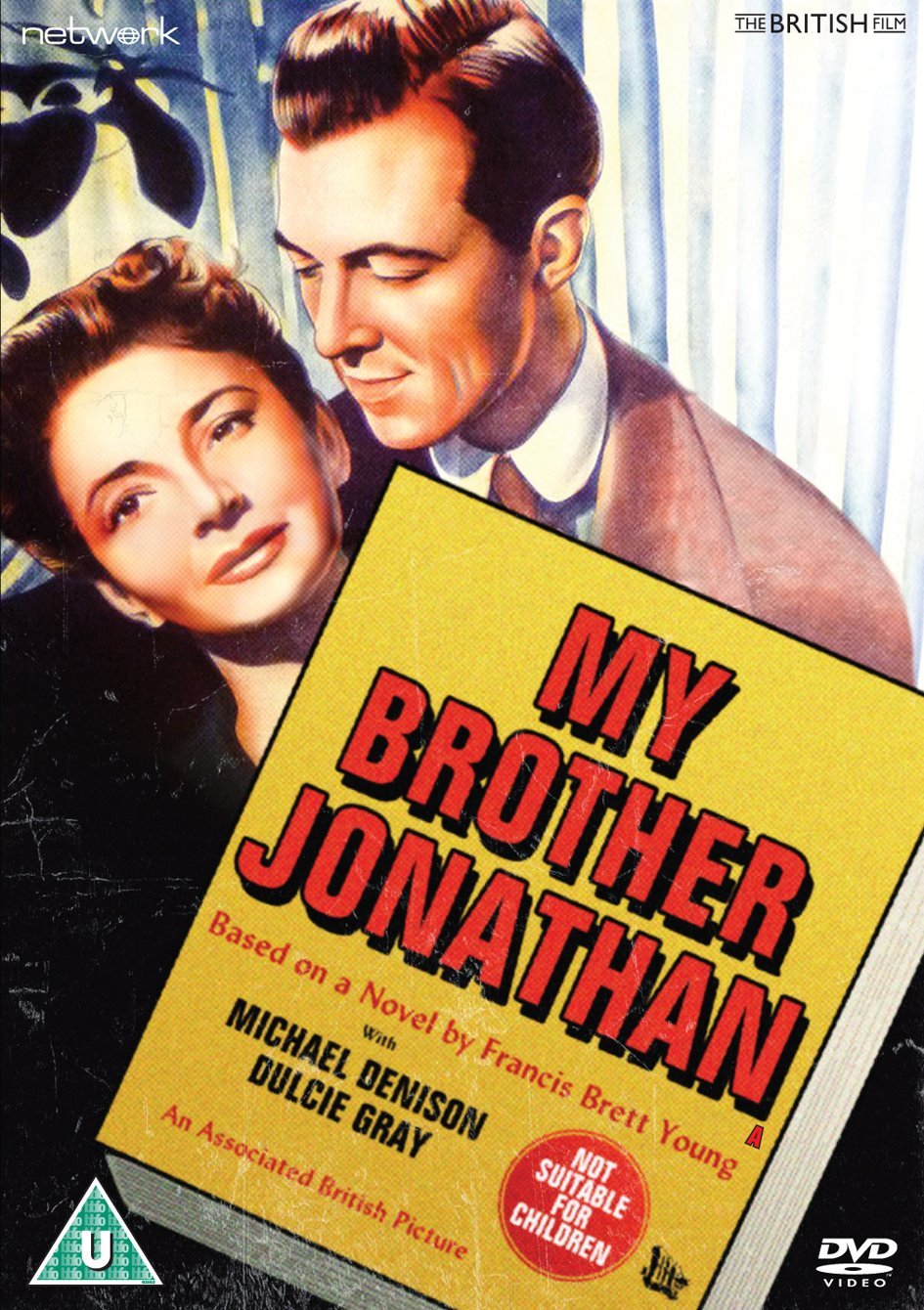

My Brother Jonathan

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd March 2015). |

|

The Film

My Brother Jonathan (Harold French, 1948) My Brother Jonathan (Harold French, 1948)

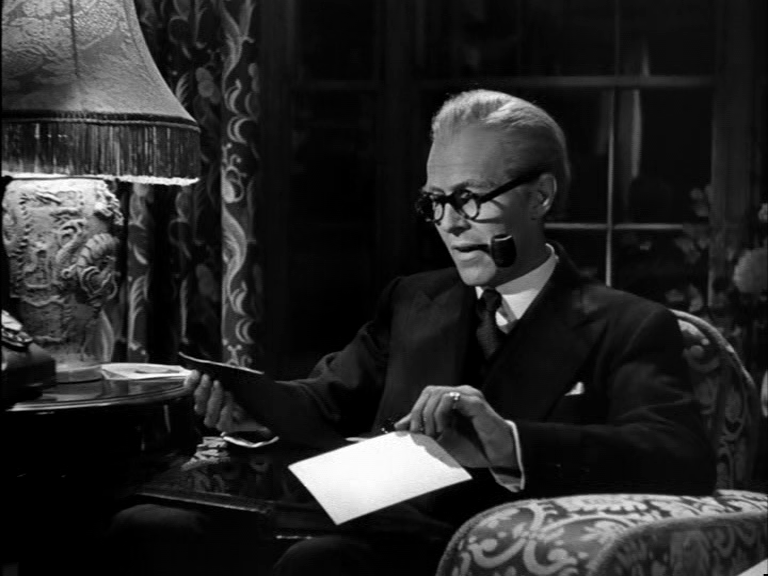

This film, a big screen adaptation of Francis Brett Young’s novel of the same title, was ‘the flagship’ of ABPC’s post-war productions, an ‘accomplished and expensive-looking’ picture (Spicer, 2003: 48). The film, like the source novel, looked towards the archetype of the doctor-as-social crusader which had appeared in pre-war cinema (for example, King Vidor’s The Citadel, 1938) but which held increasing relevance in 1948, the year of the creation of the National Health Service (ibid.). The release of My Brother Jonathan came closely after the releases of a handful of films that featured similarly tireless medical professionals, including Anthony Kimmins’ Mine Own Executioner (1947, recently released by Network on Blu-ray and reviewed by us here). My Brother Jonathan begins with a voiceover (‘The midlands. Nature’s loveliness; man’s desecration. Iron and coal are the gods men serve’). In the village of Brimsley, Jonathan Dakers (Michael Denison), a General Practitioner, awaits the return of his son Tony (Pete Murray), who is a military doctor. Tony reveals to his father that ‘I’m going to chuck medicine’; to this, Jonathan observes, ‘I suppose fathers are always overkeen on their sons following in their footsteps. A form of selfishness, really’. Jonathan promises to tell Tony a story from his past, beginning by telling Tony of his childhood with his brother Harold (or ‘Hal’) (Ronald Howard). Jonathan and Harold’s childhood was spent with their father Eugene (James Robertson Justice), a poet, and their domineering mother (Mary Clare). Eugene’s work as a poet barely fed the family, and they were considered the shame of the village, referred to as ‘strange’ by Brimley’s other inhabitants. Ashamed of their poverty, Mrs Dakers warns her sons to tell the other children that they failed their entry examinations rather than admit that the family does not have enough money to pay for the private education from which many of the other families in the village benefit. However, during this period Hal shows a keen ability to play cricket; and Jonathan strikes up a friendship with a young girl, Edie Martyn. Years afterwards, Jonathan is training as a doctor, hoping to enter into the field of surgery in London. He is surprised once again to meet Edie Martyn (Beatrice Campbell), who is part of a suffragette march. Whilst Jonathan has eyes for Edie, Edie has eyes for Jonathan’s cricket-playing brother Hal, who Edie describes as ‘so attractive and successful’. Jonathan’s career as a surgeon is struck short when his father is killed after being hit by ‘one of those frightful motor cars’. Having promised Eugene that he would take care of Hal, and discovering that the money he inherited from Uncle William has been squandered by Eugene, Jonathan is forced to give up his dream of becoming a surgeon, instead taking a place as a General Practitioner in a ‘working class practice’.  Taking his new position as a GP under Dr Hammond (Finlay Currie), Jonathan is introduced to Hammond’s daughter Rachel (Dulcie Gray). There, Jonathan is introduced to the politics of medicine. Hammond tells Jonathan that his predecessor at the surgery undermined Hammond and eventually opened up his own surgery to ‘rob’ the older doctor of his patients. The town is dominated by a foundry owned by Sir Joseph Higgins (Arthur Young), which suffers from a high rate of accidents, and Jonathan crusades for better treatment for the working class members of the community through making radical changes to the local hospital’s policies – to the point that Higgins scornfully says of him, ‘I’m afraid he [Dakers] rather fancies himself as the “worker’s friend”’. Taking his new position as a GP under Dr Hammond (Finlay Currie), Jonathan is introduced to Hammond’s daughter Rachel (Dulcie Gray). There, Jonathan is introduced to the politics of medicine. Hammond tells Jonathan that his predecessor at the surgery undermined Hammond and eventually opened up his own surgery to ‘rob’ the older doctor of his patients. The town is dominated by a foundry owned by Sir Joseph Higgins (Arthur Young), which suffers from a high rate of accidents, and Jonathan crusades for better treatment for the working class members of the community through making radical changes to the local hospital’s policies – to the point that Higgins scornfully says of him, ‘I’m afraid he [Dakers] rather fancies himself as the “worker’s friend”’.

With the outbreak of the First World War, both Jonathan and Harold enlist. However, Jonathan’s is told he’s ‘indispensible’ at home and, frustratedly, must see his brother go to war alone. ‘You’ve been doing a worthwhile job all the time whilst I’ve simply been playing at life’, Hal tells Jonathan before he departs. Jonathan and Rachel grow closer, but this tentative relationship is disrupted when news reaches home that Hal has been killed in action; Jonathan discovers that Edie is pregnant with Hal’s child, and to save Edie and the child from shame, Jonathan marries Edie. Initially resistant to the idea (‘You’ve fought Harold’s battles for him. You’ve done enough’, she says), Edie is eventually persuaded to marry Jonathan. However, Edie soon contracts a fatal illness and dies, leaving Jonathan to marry his true love, Rachel, and raise Edie and Hal’s son as his own. That son is, of course, Tony. Jonathan’s training as a doctor is set against the backdrop of the suffragette movement, something which in a number of scenes patriarchal characters are shown to be mocking – much as Higgins later mocks Jonathan’s attempts to improve the treatment of his proletarian clients. During the scenes depicting Jonathan’s medical training in London, a suffragette parade is seen passing outside the window. ‘Give women the vote; they’ll vote for the best looking candidate every time’, one of the characters says dryly. Edie is a thoroughly modern woman, allied with the suffragette movement, telling Jonathan that ‘I only know that I want to live. I want to taste all the adventures in the world’. For both her and Jonathan, the future is represented by Hal: Edie is in love with Hal, and Jonathan has promised his father that he will act as Hal’s guardian. Edie refuses Jonathan’s original proposal of marriage (‘I don’t think I want to marry anyone’), enabling her to pursue Hal: ‘We belong to a different age’, Edie tells Jonathan, ‘Harold belongs to my generation’. However, the death of Hal throws them together, and Jonathan forsakes his own personal happiness, in terms of his relationship with Rachel (at least, until Edie’s death), to demonstrate the same sense of duty which characterises his work as a GP. The film contrasts two versions of masculinity: the dedicated Jonathan is set against his brother Harold/Hal, ‘the debonair playboy […] for whom life is a smooth success not a struggle’ (Spicer, op cit.: 48). Both Harold and Edie die during the course of the narrative, and Marcia Landy has observed that the film ‘kills off the romantic and pleasure-seeking couple [Harold and Edie] to make room for the socially conscious figures whose satisfaction is through work and service to others’, thus foregrounding ‘the ethos of altruism and service’ (Landy, 1991: 277). Jonathan’s struggles against his overbearing mother, the frustration of his desire to enter into surgery in London following the death of his father (and his promise to be his ‘brother’s keeper’) and the bind in which he finds himself with Edie after Harold is declared killed in action, are all obstacles to Jonathan’s personal happiness. However, the film ‘avoids succumbing to a psychological portrait’ of Jonathan, instead depicting these obstacles ‘as necessary stages of his initiation into a life of service’ (ibid.: 277-8).   The film is intact and runs for 103:55 mins (PAL).

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, My Brother Jonathan’s monochrome photography is represented well on this DVD, which has a crisp, detailed image displaying good contrast from a remarkably clean print. There are some examples of what seems to be telecine judder here and there, but nothing too distracting.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track which is clear, with audible dialogue throughout. Sadly there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes a stills gallery (1:52) and some DVD-ROM content, all as .PDF files: - An article about the film from a 1948 issue of Screen Stories (the scan includes the cover of the magazine) (3 pages); - the film’s original script (75 pages); - the film’s pressbook (3 pages).

Overall

My Brother Jonathan is a well-made picture featuring a theme (that of the dedicated professional) that was very much ‘of its time’ and fitting for the era of the film’s production and release (the early days of the NHS). It’s interesting that Network have chosen to release My Brother Jonathan at the same time as Kimmins’ Mine Own Executioner, as both films have a similar sense of focus on dedicated medical practitioners (in Kimmins’ film, a lay analyst, played by Burgess Meredith) whose insistence on serving their communities exacts a cost on their personal happiness. My Brother Jonathan gains added pathos from its flashback structure: it isn’t until a good way through the film that the audience realises that Tony, to whom Jonathan is telling this story, is actually the son of Hal and Edie. The sense of sadness at lost time is underscored by one of the lines delivered by Dr Hammond: ‘It’s a rum feeling to realise that you’re old […] One by one the people of your generation drop out until one day, I realised I’m all alone’. My Brother Jonathan is a well-made picture featuring a theme (that of the dedicated professional) that was very much ‘of its time’ and fitting for the era of the film’s production and release (the early days of the NHS). It’s interesting that Network have chosen to release My Brother Jonathan at the same time as Kimmins’ Mine Own Executioner, as both films have a similar sense of focus on dedicated medical practitioners (in Kimmins’ film, a lay analyst, played by Burgess Meredith) whose insistence on serving their communities exacts a cost on their personal happiness. My Brother Jonathan gains added pathos from its flashback structure: it isn’t until a good way through the film that the audience realises that Tony, to whom Jonathan is telling this story, is actually the son of Hal and Edie. The sense of sadness at lost time is underscored by one of the lines delivered by Dr Hammond: ‘It’s a rum feeling to realise that you’re old […] One by one the people of your generation drop out until one day, I realised I’m all alone’.

Obviously made prior to the ‘kitchen sink’ films of the late-1950s and 1960s, My Brother Jonathan’s depiction of the working classes at times seems rather patronising and noticeably absent of the kinds of defined regional accents that would become ‘acceptable’ on British screens after the release of Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top (1958) (‘Golly, who are these frightful specimens?’, Hal and Jonathan’s peers ask when they spot the two brothers). Additionally, there’s a rather conservative suggestion that both women (the suffragettes) and the working classes need the help of middle-class men to achieve their emancipation (‘I saw from the first that I had two main enemies to fight: ignorance and poverty. And only one ally: the courage […] of these people’, Jonathan says in his narration). However, these are fairly minor concerns, and given the social context, My Brother Jonathan is a fascinating film. Another adaptation of the source novel was produced for the BBC in 1985 (notably during the reform of the NHS that took place during the Thatcher era) and broadcast in five parts, with Daniel Day Lewis playing Jonathan Dakers. The presentation of the film on this DVD is more than satisfactory – but sadly there’s a lack of substantial contextual material. References: Landy, Marcia, 1991: British Genres – Cinema and Society, 1930-1960. Princeton University Press Spicer, Andrew, 2003: Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema. London: I. B. Tauris This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|