|

|

Massacre Gun AKA Minagoroshi no kenjû (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th April 2015). |

|

The Film

Massacre Gun (Hasebe Yasuhara, 1967) Massacre Gun (Hasebe Yasuhara, 1967)

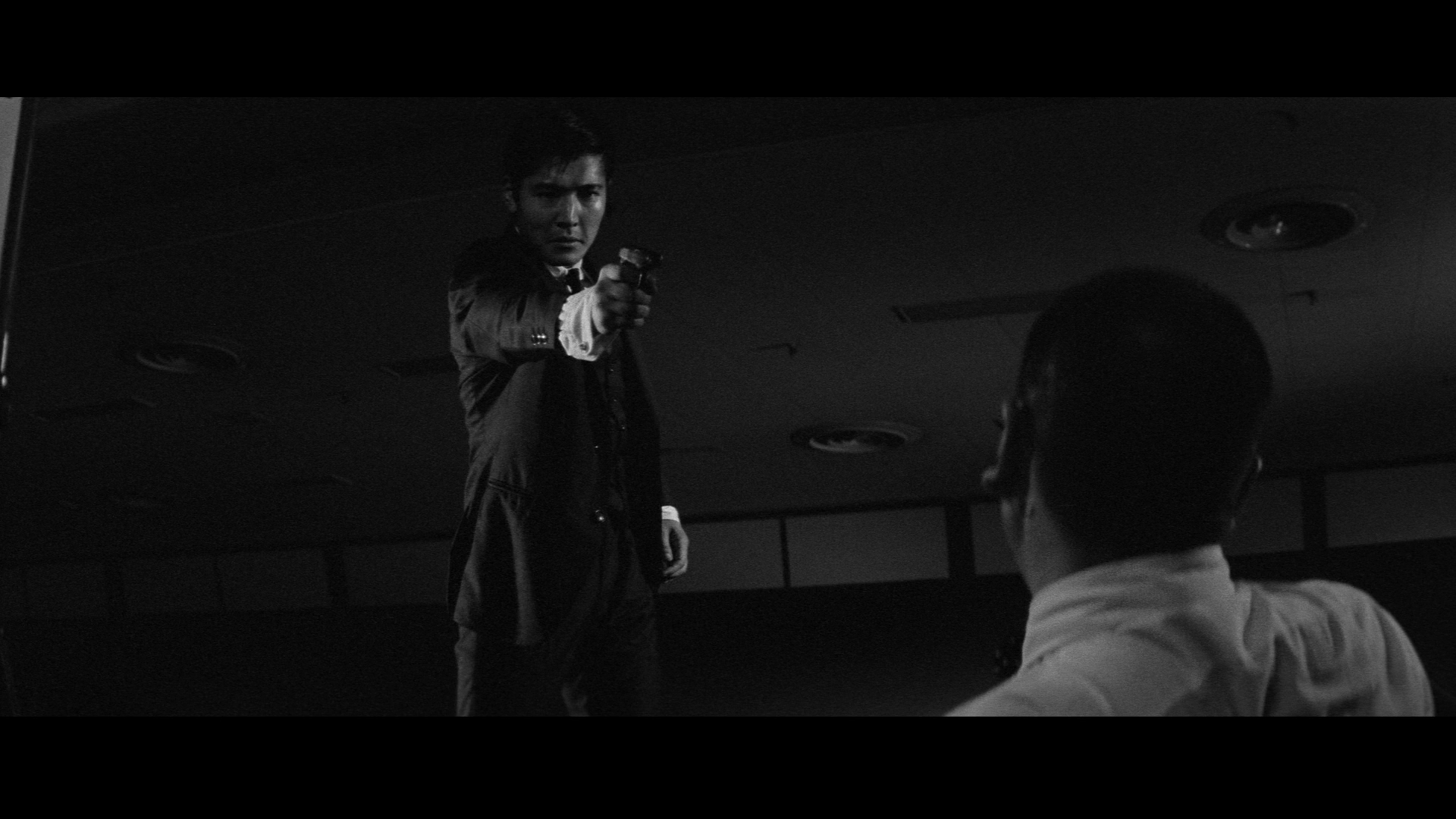

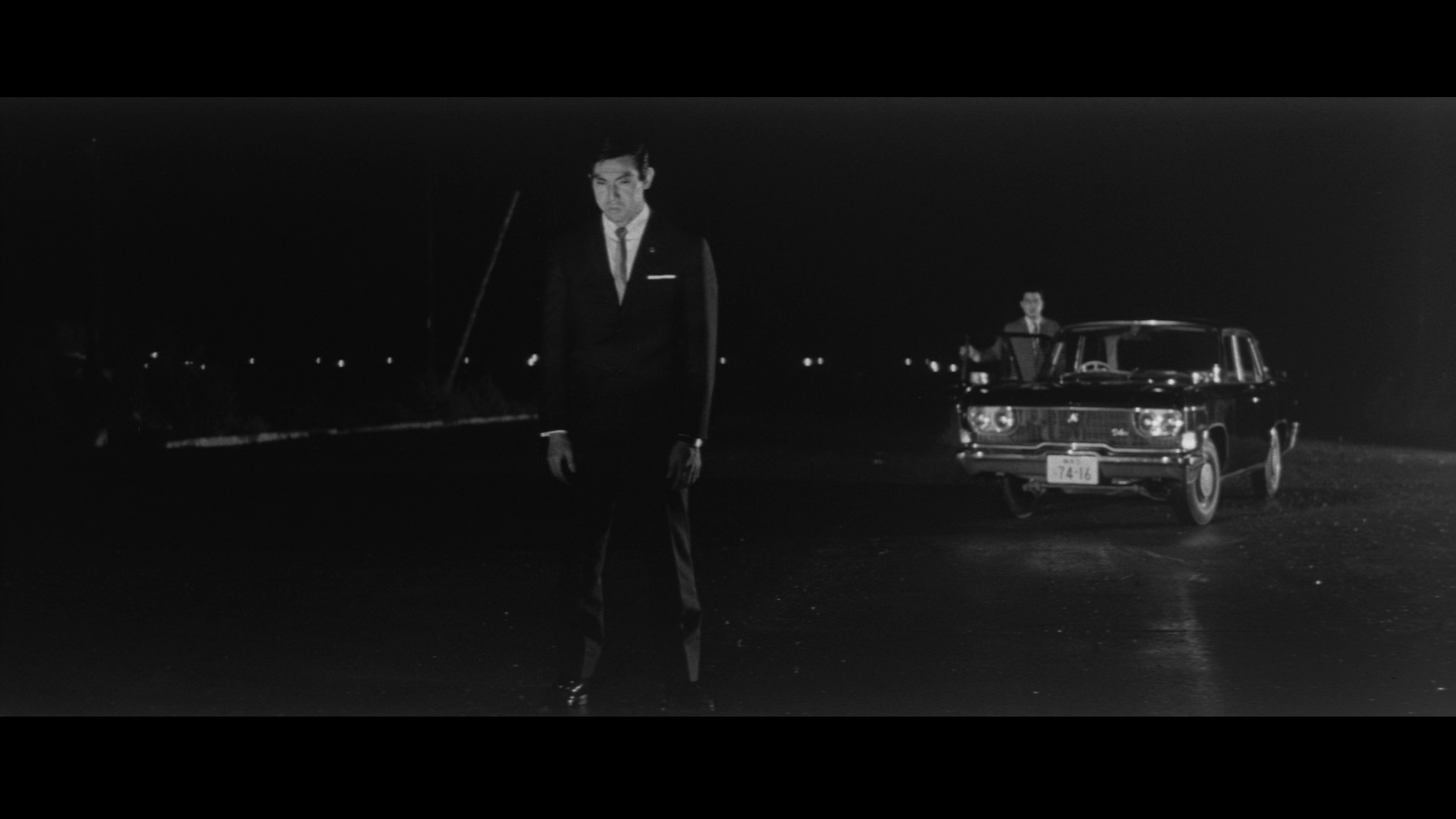

1967 proved to be an interesting year for the Japanese yakuza picture, seeing the release of Suzuki Seijun’s anarchic and subversive Branded to Kill, and two more conventional, though no less interesting, films: Nomura Takashi’s A Colt is My Passport, and the film under immediate discussion, Hasebe Yasuhara’s Massacre Gun (also sometimes referred to as Slaughter Gun). All of these films were made for Nikkatsu, starred Sishido Jô and were shot in stark monochrome (and in widescreen). Both Branded to Kill and Massacre Gun shared the same cinematographer, Nagatsuka Kazue; however, in terms of narrative, there are greater similarities between Massacre Gun and A Colt is My Passport. All three films offer variations of Nikkatsu’s brand of mukokuseki akushon pictures, sometimes referred to as ‘borderless action’ films for the ways in which they were constructed to appeal to youth audiences by taking influences (both thematic and visual, in terms of their use of chiaroscuro lighting and obtuse angles and compositions) from American films noir, the youth films popular during the 1960s and, in their ‘Servant of Two Masters’-type plots, westerns all’italiana like Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). (During the same year, in America, John Boorman’s Point Blank, which like the Nikkatsu films focused on turf wars and the tensions between organised crime and the figure of the ‘outsider’, brought the monochrome world of film noir into vivid colour and the Los Angeles sunshine; Boorman’s film provides an interesting English-language counterpoint to the Nikkatsu mukokuseki akushon films.) The mokukuseki akushon films drew on the iconography of American and European films and, though unlike their precursors (yakuza films with a period setting) they featured narratives which took place in contemporary urban Japan, the films ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182). The films were mostly shot quickly and cheaply. Branded to Kill offered a subversive self-parody of Nikkatsu’s borderless action pictures of this era, Suzuki having been hired to direct the film at the last minute and turning in a film that, to Nikkatsu’s bosses, seemed deliberately ‘incomprehensible’ (ibid.). This led to Suzuki being fired by Nikkatsu and effectively blacklisted for the next decade; Suzuki struck back by suing Nikkatsu, an act which consolidated his status as a countercultural figure. In the years following the release of Branded to Kill, Massacre Gun and A Colt is My Passport, the audience for Nikkatsu’s mokukuseki akushon pictures declined, and in the 1970s Nikkatsu turned away from the youth comedies and gangster films that had been its forte since the mid-1950s, focusing instead on the production of Roman Porno films – erotic pictures that subsequently came to define the Nikkatsu ‘brand’ for many years to come.  Although the exploits of the yakuza had featured in Japanese cinema since the silent era, the films themselves often had a period setting (and were therefore examples of jidaigeki, or period dramas). What’s more, earlier examples of the yakuza picture often featured villains who were Westernised, and by resolving conflicts with these villainous characters the moral code of the yakuza would be reinforced within the narrative. Nikkatsu’s mokukuseki akushon pictures instead featured contemporary settings, a jazz sensibility and morally-conflicted protagonists who embraced Western values. For example, Suzuki Seijun’s Tokyo Drifter (1966) features a hero whose girlfriend works in an art deco nightclub which plays Western pop music and features American-style go-go dancers. Similarly, in the Kuroda brothers’ Club Rainbow in Massacre Gun, musicians play American blues music (‘Blues is the light of the cigarette / Around the corner of the middle of the night / It’s a small dive bar where I finally arrive / With a woman seeped in melancholy’, a singer croons) and two Caucasian dancers, a male and a female, perform what could best be described as an erotic ballet, stripped to their (sparkly) underwear and presented for the objectification of the audience in the nightclub (and, by extension, the film’s audience). Equally importantly, in stark contrast to earlier yakuza pictures, the Nikkatsu films of the 1960s often featured an implicit critique of the code of the yakuza that was buried within an exploration of inter-generational conflict, with the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans frequently depictured as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, often exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. This would lead into the jitsuroku films of the 1970s, which used documentary filmmaking techniques (handheld cameras, abrupt editing rhythms) to depict the yakuza as little more than animalistic street thugs motivated by self-interest. (The jitsuroku films are usually cited as beginning with Fukasaku Kenji’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity in 1973.) Although the exploits of the yakuza had featured in Japanese cinema since the silent era, the films themselves often had a period setting (and were therefore examples of jidaigeki, or period dramas). What’s more, earlier examples of the yakuza picture often featured villains who were Westernised, and by resolving conflicts with these villainous characters the moral code of the yakuza would be reinforced within the narrative. Nikkatsu’s mokukuseki akushon pictures instead featured contemporary settings, a jazz sensibility and morally-conflicted protagonists who embraced Western values. For example, Suzuki Seijun’s Tokyo Drifter (1966) features a hero whose girlfriend works in an art deco nightclub which plays Western pop music and features American-style go-go dancers. Similarly, in the Kuroda brothers’ Club Rainbow in Massacre Gun, musicians play American blues music (‘Blues is the light of the cigarette / Around the corner of the middle of the night / It’s a small dive bar where I finally arrive / With a woman seeped in melancholy’, a singer croons) and two Caucasian dancers, a male and a female, perform what could best be described as an erotic ballet, stripped to their (sparkly) underwear and presented for the objectification of the audience in the nightclub (and, by extension, the film’s audience). Equally importantly, in stark contrast to earlier yakuza pictures, the Nikkatsu films of the 1960s often featured an implicit critique of the code of the yakuza that was buried within an exploration of inter-generational conflict, with the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans frequently depictured as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, often exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. This would lead into the jitsuroku films of the 1970s, which used documentary filmmaking techniques (handheld cameras, abrupt editing rhythms) to depict the yakuza as little more than animalistic street thugs motivated by self-interest. (The jitsuroku films are usually cited as beginning with Fukasaku Kenji’s Battles Without Honour and Humanity in 1973.)

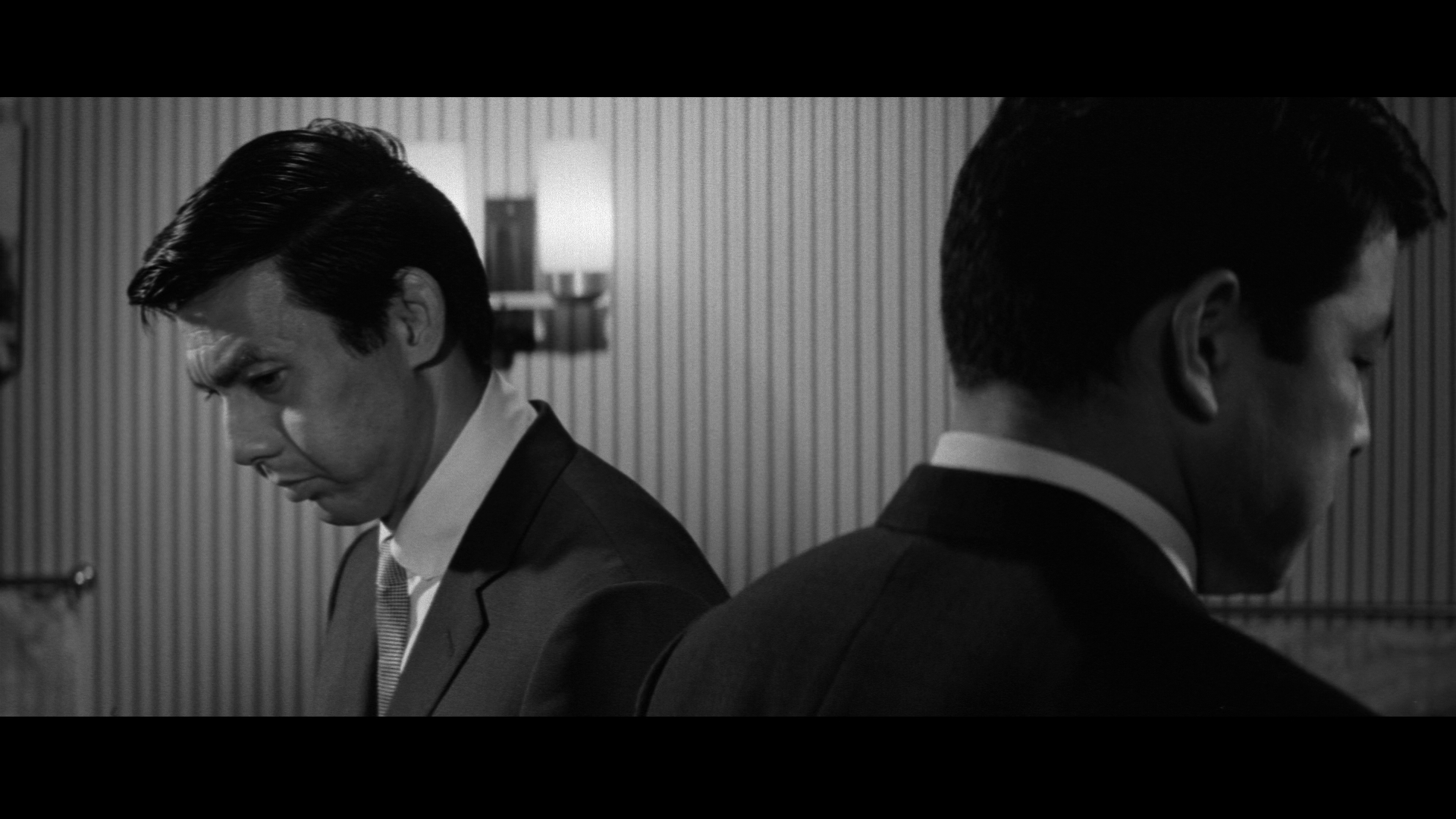

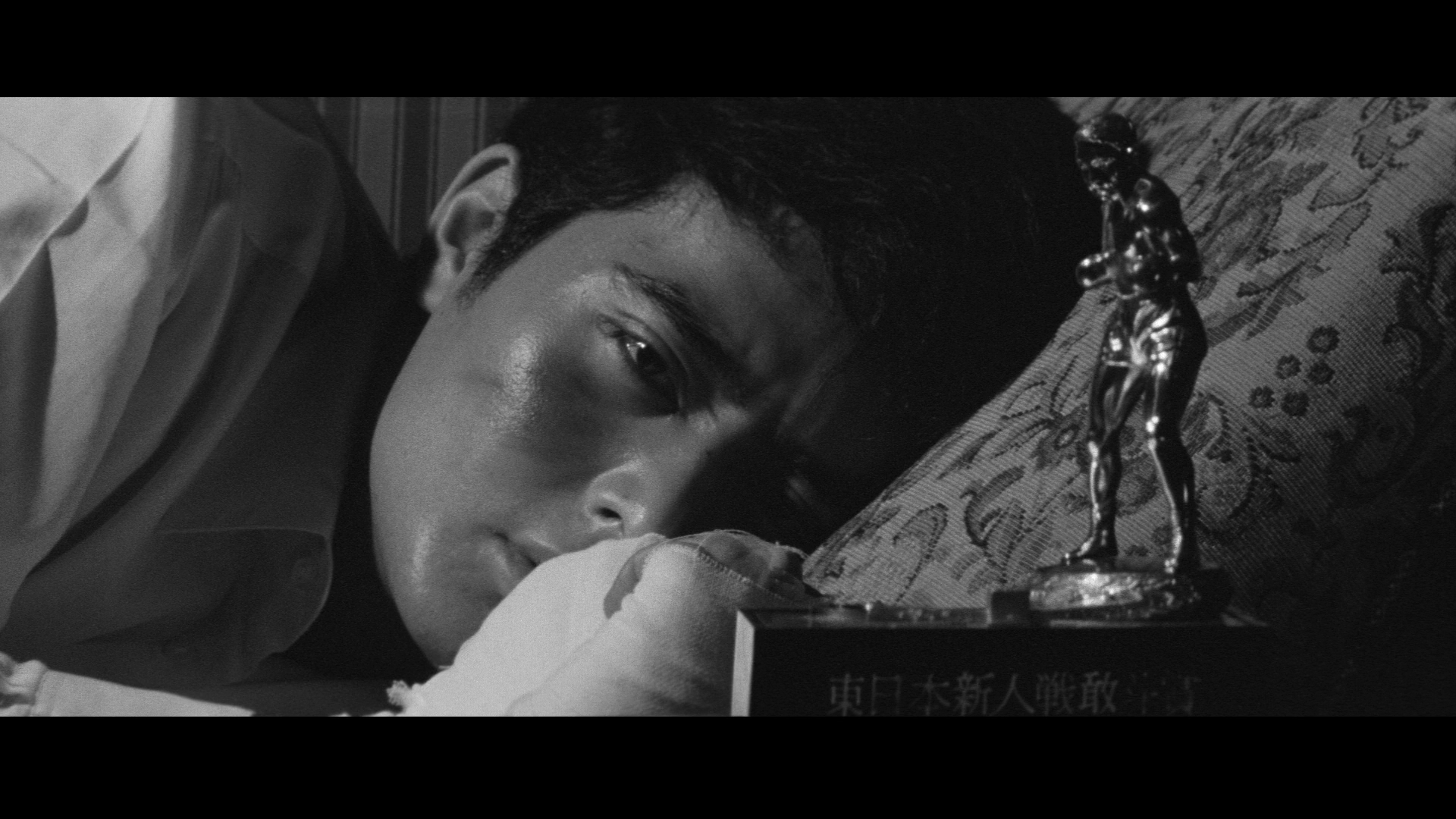

This conflict between the values of the yakuza, embodied in the patriarchal figure of a yakuza boss, and the ‘young blood’ is central to Massacre Gun. As the film opens, Kuroda (Shishido) is ordered by Boss Akazawa (Kanda Takashi) to kill Akazawa’s former lover, who ran away from Akazawa to be with Kuroda. Kuroda obeys, but his unquestioning obedience of Akazawa’s order is challenged by Kuroda’s younger brother Saburo (Jirô Okazaki).  Saburo is a promising boxer in a club sponsored by Akazawa, and has potential as a professional boxer. Displeased with Akazawa’s ordering of Kuroda to kill the girl, Saburo confronts Akazawa, who tells the young man, ‘Saburo, I’ve been extraordinarily kind to you. But if you return kindness with hostility, you’ll regret it’. Saburo quits, and in an act of spite Akazawa has Saburo’s hands broken, thereby destroying Saburo’s promising future as a boxer. Saburo returns to his brothers Kuroda and Eiji (Fuji Tatsuya) at the nightclub they own, the Club Rainbow. Both Kuroda and Eiji have tried to shelter Saburo from the yakuza lifestyle by encouraging him to pursue a ‘legitimate’ career. Seeing the injuries sustained by Saburo, Eiji romises to strike back at Akazawa; however, Kuroda tells Eiji to exercise restraint. Saburo is a promising boxer in a club sponsored by Akazawa, and has potential as a professional boxer. Displeased with Akazawa’s ordering of Kuroda to kill the girl, Saburo confronts Akazawa, who tells the young man, ‘Saburo, I’ve been extraordinarily kind to you. But if you return kindness with hostility, you’ll regret it’. Saburo quits, and in an act of spite Akazawa has Saburo’s hands broken, thereby destroying Saburo’s promising future as a boxer. Saburo returns to his brothers Kuroda and Eiji (Fuji Tatsuya) at the nightclub they own, the Club Rainbow. Both Kuroda and Eiji have tried to shelter Saburo from the yakuza lifestyle by encouraging him to pursue a ‘legitimate’ career. Seeing the injuries sustained by Saburo, Eiji romises to strike back at Akazawa; however, Kuroda tells Eiji to exercise restraint.

Kuroda visits Akazawa and quits working for him. Behind Kuroda’s back, Akazawa asserts that ‘He’ll soon realise that he won’t be able to survive without me’. Meanwhile, Kuroda pays a visit to his old friend Shirasaka (Nitani Hideaki), who is still a member of Akazawa’s group. Kuroda and Shirasaka are old, close friends; but Kuroda’s antagonism with Akazawa puts their friendship under strain. Returning to the Club Rainbow, Kuroda discovers that the interior has been destroyed by Akazawa’s gang members. When Club Rainbow reopens, Shirasaka visits and attempts to persuade Kuroda not to challenge Akazawa. Shirasaka ends the conversation by telling Kuroda that ‘our friendship is over’. Following this, Kuroda decides to ‘strike first’ against Akazawa, ‘or we’ll be crushed’. Kuroda and his brothers take over various businesses owned by Akazawa, including the boxing gym and various restaurants, nightclubs and a bowling alley. ‘Let’s take over the city in one fell swoop’, the naïve Saburo declares eagerly. Torn between his friendship with Kuroda and his obedience to Akazawa, Shirasaka finds himself in a tight spot. He offers information to Kuroda, telling him when and where a gambling operation of Akazawa’s is taking place. Kuroda, Eiji and Saburo raid the gambling den, provoking the ire of Akazawa, who plots to strike back against the rogue brothers. Akazawa achieves this through one of his underbosses, Konno, who sets Kuroda up for an ambush by using a low-ranking yakuza to feed false information to Kuroda about the location of one of Akazawa’s gambling dens. However, Kuroda miraculously manages to escape this trap. Akazawa retaliates by abducting Saburo. Kuroda and Eiji rescue their younger brother, but as they are about to depart, Saburo, who has been mocked by Akazawa, shoots and kills the yakuza boss. Following the death of Akazawa, Shirasaka takes over the clan and is finally forced to take action against his former friend Kuroda. The stage is set for a final, fatal and inevitable showdown between these two close allies.  In the opening sequence, Kuroda demonstrates his obedience to Akazawa by obeying the boss’ demand that he kill his lover. As Kuroda is given this order by Akazawa, the camera gazes down from a high-angle, emphasising how small Kuroda is within this moment. Similar high-angle compositions (almost an overhead shot) are repeated several times throughout the film, when Kuroda and his brothers are threatened or surrounded by Akazawa’s hoodlums, and during the abduction of Saburo by Akazawa’s men. Kuroda’s unquestioning obedience of Akazawa’s will is reinforced when, after he has driven the car containing his lover’s body into the river, Saburo – the youngest of the brothers and the most compassionate – tells Kuroda, ‘She was in love with you, brother [….] You’re too cruel’. This is no surprise to Kuroda, who looks shamed. ‘Are you that scared of Boss Akazawa, brother?’, Saburo asks, ‘Do you have to obey him in everything he tells you?’ In the opening sequence, Kuroda demonstrates his obedience to Akazawa by obeying the boss’ demand that he kill his lover. As Kuroda is given this order by Akazawa, the camera gazes down from a high-angle, emphasising how small Kuroda is within this moment. Similar high-angle compositions (almost an overhead shot) are repeated several times throughout the film, when Kuroda and his brothers are threatened or surrounded by Akazawa’s hoodlums, and during the abduction of Saburo by Akazawa’s men. Kuroda’s unquestioning obedience of Akazawa’s will is reinforced when, after he has driven the car containing his lover’s body into the river, Saburo – the youngest of the brothers and the most compassionate – tells Kuroda, ‘She was in love with you, brother [….] You’re too cruel’. This is no surprise to Kuroda, who looks shamed. ‘Are you that scared of Boss Akazawa, brother?’, Saburo asks, ‘Do you have to obey him in everything he tells you?’

When Saburo quits Akazawa’s boxing club, in reaction to Kuroda’s assassination of the young woman, he tells Akazawa that ‘I won’t be your dog like my brother [Kuroda]’. In response, Akazawa has Saburo’s hands broken, thereby destroying Saburo’s promising future as a boxer and ironically precipitating Saburo’s movement into the shadowy criminal world of Kuroda. Following this, Saburo demonstrates an increasing eagerness to strike back at Akazawa, leading to Saburo’s execution of Akazawa – and, ultimately, the showdown between Kuroda and Shirasaka. This development within the narrative brings to mind Robert Siodmak’s classic American film noir The Killers (1946), in which the flashback structure slowly reveals that former boxer Ole Andreson’s (Burt Lancaster) breaking of the bones in his right hand during a match precipitated his freefall into a life of crime. (Viewers might also recall the fate that befalls Django, played by Franco Nero, in Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 western all’italiana Django.) In this context, the breaking of Saburo’s hands is an apt metaphor for the death of his dream of becoming a professional boxer and his increasingly criminal behaviour, thus reinforcing the fatalistic tone of a film that ends with two former friends (Kuroda and Shirasaka) forced into an inevitable conflict with one another. As Shirasaka tells Shino towards the end of the film, in response to her query as to whether his conflict with Kuroda can be halted, ‘It’s like a car rolling downhill. There’s no stopping it now’. Saburo’s injury also signals the downfall of Kuroda and Eiji. The shattering of Saburo’s hands, and the collapse of his future as a boxer, takes a toll on all three brothers. Kuroda and Eiji have tried to shield Saburo from a life of crime, even though the gym at which he trains is owned by Akazawa. ‘We tried to give Saburo an honest life, didn’t we?’, Eiji asks Kuroda. Even after the crippling of Saburo’s hands, Kuroda demonstrates patience by turning the other cheek towards Akazawa: Eiji threatens to strike back at Akazawa, but Kuroda warns him, ‘Don’t get involved’. Later, whilst Akazawa’s gangsters smash up the Club Rainbow, Kuroda offers a similar warning, telling Eiji, ‘Just leave them. Let them do what they want’. On the other hand, as the narrative progresses Saburo demonstrates an increasing predilection for violence, which is foreshadowed when, after discovering that Kuroda has obeyed Akazawa’s order to kill his lover, Saburo savagely beats his sparring partner into unconsciousness – an act which shocks the other patrons of the boxing gym.  As Kuroda, Eiji and Saburo strike at more and more of Akazawa’s businesses, Saburo demonstrates an increasing appetite for crime, asserting eagerly that the trio should ‘take over the city in one fell swoop’. After the brothers raid Akazawa’s gambling den, Saburo’s girlfriend tells him, ‘You’ve changed, Saburo. You’re no different than one of Akazawa’s thugs [….] You’re not the person you think you are’. ‘I apologise’, Saburo tells her before adding, in recognition of the way in which his purpose in life has changed, ‘That’s my job’. Later, Saburo’s girlfriend tells Saburo, just before he is abducted by Akazawa’s hoods, that ‘You don’t have to end up like your brothers: you’re different from them’. Saburo is abducted by Akazawa’s goons and rescued by his brothers but ultimately, Saburo’s transition from boxer to criminal is confirmed when, after Kuroda and Eiji rescue him from Akazawa’s grasp, Saburo chooses to shoot and kill the ageing yakuza boss. (During his period of capture by Akazawa, Akazawa mocked Saburo by telling him, ‘If you hadn’t defied me, you’d be a champion by now’.) As Kuroda, Eiji and Saburo strike at more and more of Akazawa’s businesses, Saburo demonstrates an increasing appetite for crime, asserting eagerly that the trio should ‘take over the city in one fell swoop’. After the brothers raid Akazawa’s gambling den, Saburo’s girlfriend tells him, ‘You’ve changed, Saburo. You’re no different than one of Akazawa’s thugs [….] You’re not the person you think you are’. ‘I apologise’, Saburo tells her before adding, in recognition of the way in which his purpose in life has changed, ‘That’s my job’. Later, Saburo’s girlfriend tells Saburo, just before he is abducted by Akazawa’s hoods, that ‘You don’t have to end up like your brothers: you’re different from them’. Saburo is abducted by Akazawa’s goons and rescued by his brothers but ultimately, Saburo’s transition from boxer to criminal is confirmed when, after Kuroda and Eiji rescue him from Akazawa’s grasp, Saburo chooses to shoot and kill the ageing yakuza boss. (During his period of capture by Akazawa, Akazawa mocked Saburo by telling him, ‘If you hadn’t defied me, you’d be a champion by now’.)

The tragic core of the film is the relationship between the outsider Kuroda and his friend Shirasaka, both of whom are the closest in line to take over from Akazawa. After quitting his work for Akazawa, Kuroda tells his friend Shirasaka that, ‘I’ve long thought about retiring from Akazawa’s mob [….] It was either you or me to take over Akazawa’s mantle. But I was an outsider, not trained from boyhood like you. So I decided to withdraw when the time came [….] I wanted to say farewell to you with a smile’. When Kuroda leaves, Shirasaka’s wife Shino (Sawa Tamaki) tells her husband, ‘You were destined to go your separate ways, you and Kuroda. You both used to be so close. I was jealous of you guys’. Later in the film, Shirasaka realises that Kuroda may challenge Akazawa, and he warns Kuroda not to do so. ‘When we meet next, it may be as enemies’, Kuroda asserts. ‘Better if we’d been enemies from the beginning’, Shirasaka tells him, ‘Kuroda, our friendship is over now’. Following this exchange, as if freed from his obligations towards Shirasaka, Kuroda changes his formerly passive, tolerant stance towards Akazawa, telling his brother Eiji, ‘Strike first or we’ll be crushed’.  Meanwhile, Shirasaka’s wife highlights the extent to which Shirasaka’s obedience towards Akazawa dominates his life: ‘You’ll never be able to escape this town’, she declares, ‘Akazawa means more to you than I do [….] I know you’d even abandon love for obligation’. Later, she confronts Kuroda, after Shirasaka has given Kuroda information about Akazawa’s operations, and tells Kuroda that the war between Kuroda and Akazawa ‘is killing my husband’. At the end of the film, Kuroda and Shirasaka acknowledge that the conflict between them that has been set in place by Akazawa and, to a lesser extent, Saburo is undesirable to either one of them and necessary only within the context of the yakuza code. ‘I really never wanted to fight you’, Shirasaka asserts as he and Kuroda face one another. ‘It’s too late to stop’, Kuroda responds. ‘We have no choice now’, Shirasaka adds fatalistically. Meanwhile, Shirasaka’s wife highlights the extent to which Shirasaka’s obedience towards Akazawa dominates his life: ‘You’ll never be able to escape this town’, she declares, ‘Akazawa means more to you than I do [….] I know you’d even abandon love for obligation’. Later, she confronts Kuroda, after Shirasaka has given Kuroda information about Akazawa’s operations, and tells Kuroda that the war between Kuroda and Akazawa ‘is killing my husband’. At the end of the film, Kuroda and Shirasaka acknowledge that the conflict between them that has been set in place by Akazawa and, to a lesser extent, Saburo is undesirable to either one of them and necessary only within the context of the yakuza code. ‘I really never wanted to fight you’, Shirasaka asserts as he and Kuroda face one another. ‘It’s too late to stop’, Kuroda responds. ‘We have no choice now’, Shirasaka adds fatalistically.

In stark juxtaposition with Suzuki’s surreal and comic book-esque Branded to Kill, Hasebe’s approach in Massacre Gun is gritty and naturalistic. This was only Hasebe’s second film as a director, following Black Tight Killers (1966). In Black Tight Killers, the hero, played by Kobayashi Akira, is hunted down by a group of go-go dancers-cum-assassins who use bubble gum and LPs as weapons. The contrast between the outrageous Black Tight Killers, shot in vivid colour, and the moody noir-esque Massacre Gun, with its equally moody monochrome photography, established Hasebe’s tendency to oscillate between camp excess and hardboiled melodrama – although some of his later Roman Porno films, including Assault! Jack the Ripper (1976) and Rape! 13th Hour (1977), foreground how these two approaches often co-exist within the same film, whilst also allowing Hasebe to explore what seems to be one of his overriding themes, a forthright examination of the bestial aspects of human nature.   The film is uncut and runs for 89:01 mins.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up almost 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The widescreen monochrome photography looks excellent on this Blu-ray release. The transfer is crisp and beautiful, with strong contrast levels: rich blacks are complemented by strong mid-tones, showing off the chiaroscuro lighting that dominates much of the film. For much of the film cinematographer Nagatsuka Kazue uses wide-angle lenses, with deep focus, giving the sets and staging a sense of depth and making strong use of lines that recede into the distance (counter-tops in the nightclubs, for example); this sense of depth within the original photography is communicated beautifully by the level of detail visible within this high-definition presentation of the film. Organic film grain is present throughout, with no evidence of harmful digital tinkering (either sharpening or noise reduction). NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track (in Japanese). It’s a clean and clear track with excellent range, noticeable especially when the punchy jazzy score appears. Optional English subtitles are provided. These are clear and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes in interview with Sishido Jô (17:38). Shishido reflects on his career as an actor, not just his work on Massacre Gun. He discusses his approach to acting and his work for Suzuki Seijun. Also included is an interview with Tony Rayns (36:26). This is essentially a video essay, with Rayns discussing the history of Nikkatsu studios from the 1920s to the era of the Roman Porno films. This is an excellent feature which gives Massacre Gun a strong sense of context. Finally, the disc includes a trailer for the film (2:25) and a stills gallery (14 images). The release also includes a DVD copy of the film (which also contains all of the extra features that are on the Blu-ray), reversible cover art on the sleeve and a lavish booklet which contains a very good essay by Jasper Sharp.

Overall

Massacre Gun is a superb example of Nikkatsu’s borderless action ethos, and it’s a film that’s often overlooked in discussions of Nikkatsu’s yakuza pictures of the 1960s. It’s fairly little-seen, in relation to some of its contemporaries (for example, Suzuki’s Branded to Kill). This Blu-ray release from Arrow, limited to 3000 copies, contains an outstanding presentation of the film and some excellent contextual material. The piece by Tony Rayns is particularly interesting, both for existing fans of these films and newcomers. In sum, this is an excellent release of an oft-neglected film, which complements some of Arrow’s other releases (for example, the Stray Cat Rock set, which features films directed by Hasebe, and their upcoming release of Hasebe’s Retaliation, 1969). References: Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|