|

|

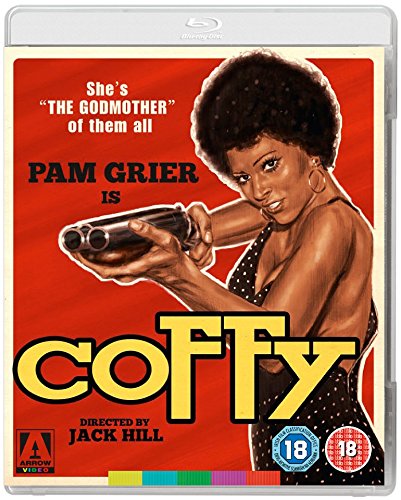

Coffy (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st April 2015). |

|

The Film

Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973) Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973)

The legend of how Pam Grier became one of the most iconic black women to ever grace American cinema reputedly begins with how Grier was ‘discovered’ during her tenure as a lowly switchboard operator at American International Pictures. Along with Tamara Dobson’s performance in Cleopatra Jones (Jack Starrett, 1973), Grier broke the mold for how African American women are represented on screen in her roles as the strong, confident protagonists of a group of ‘blaxploitation’ films made during the early/mid-1970s; the most famous of these are Jack Hill’s Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974, initially planned as a sequel to Coffy), Sheba, Baby! (William Girdler, 1973) and Friday Foster (Arthur Marks, 1975). Where African American women had traditionally been depicted as servants or deviants, Grier essayed a new representation of black women as strong, independent and utterly capable. Even in blaxploitation films more generally, black women were largely represented as sex objects, with the characters ‘emerg[ing] as sex toys for the films’ [male] protagonists’ (Lawrence, 2007: np). Films such as Coffy, in which African American women are depicted as ‘strong, three-dimensional characters’, therefore ‘work in direct opposition to the traditional portrayals of black women’ both in mainstream cinema and in the more specific context of blaxploitation films. The film begins violently, with Coffy (Grier) killing a street dealer and his boss with a shotgun, at point blank range, after allowing both men to believe she is simply what they refer to as ‘tail’. (‘I know what you want too… And you’re gonna get it’, Coffy tells them ironically as the two men drive her to a seedy apartment where they intend to seduce her.) Coffy is a vigilante, murdering drug pushers as revenge for the fate of her sister, who was turned onto dope at the age of eleven and forced to work as a prostitute. Coffy’s method is to use her sexuality to render her targets vulnerable before killing them.  Coffy is also a nurse at the local hospital. The next day, at work, she encounters her friend and former lover, Carter (William Elliott), a police officer. Carter tells Coffy of the murders of the drug dealers, not knowing that she committed them. Meanwhile, Coffy’s lover, Howard Brunswick (Booker Bradshaw), announces that he intends to run for Congress. However, unbeknownst to Coffy, Brunswick is corrupt and is involved with a mob boss, Arturo Vitroni (Allan Arbus). Coffy is also a nurse at the local hospital. The next day, at work, she encounters her friend and former lover, Carter (William Elliott), a police officer. Carter tells Coffy of the murders of the drug dealers, not knowing that she committed them. Meanwhile, Coffy’s lover, Howard Brunswick (Booker Bradshaw), announces that he intends to run for Congress. However, unbeknownst to Coffy, Brunswick is corrupt and is involved with a mob boss, Arturo Vitroni (Allan Arbus).

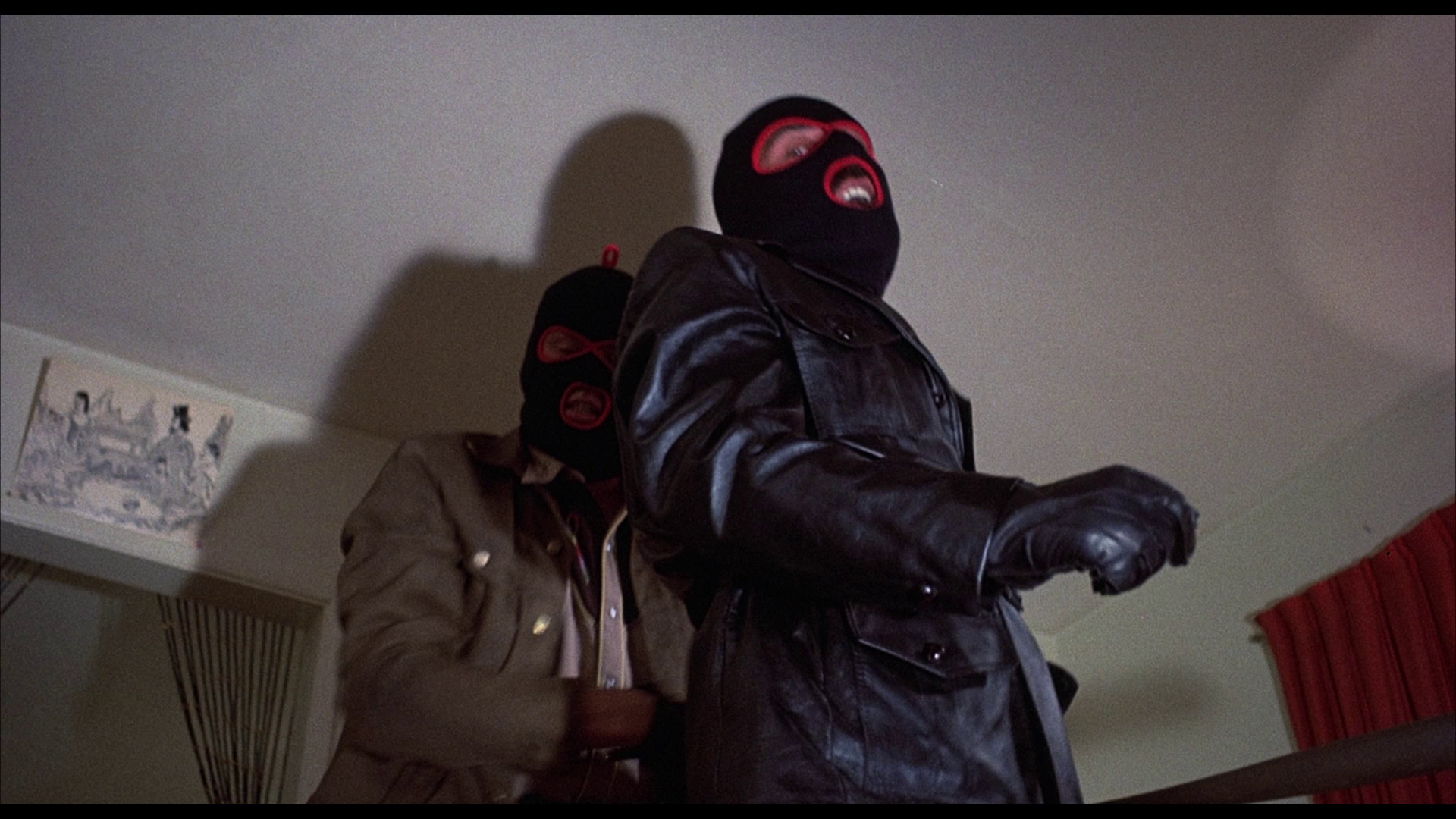

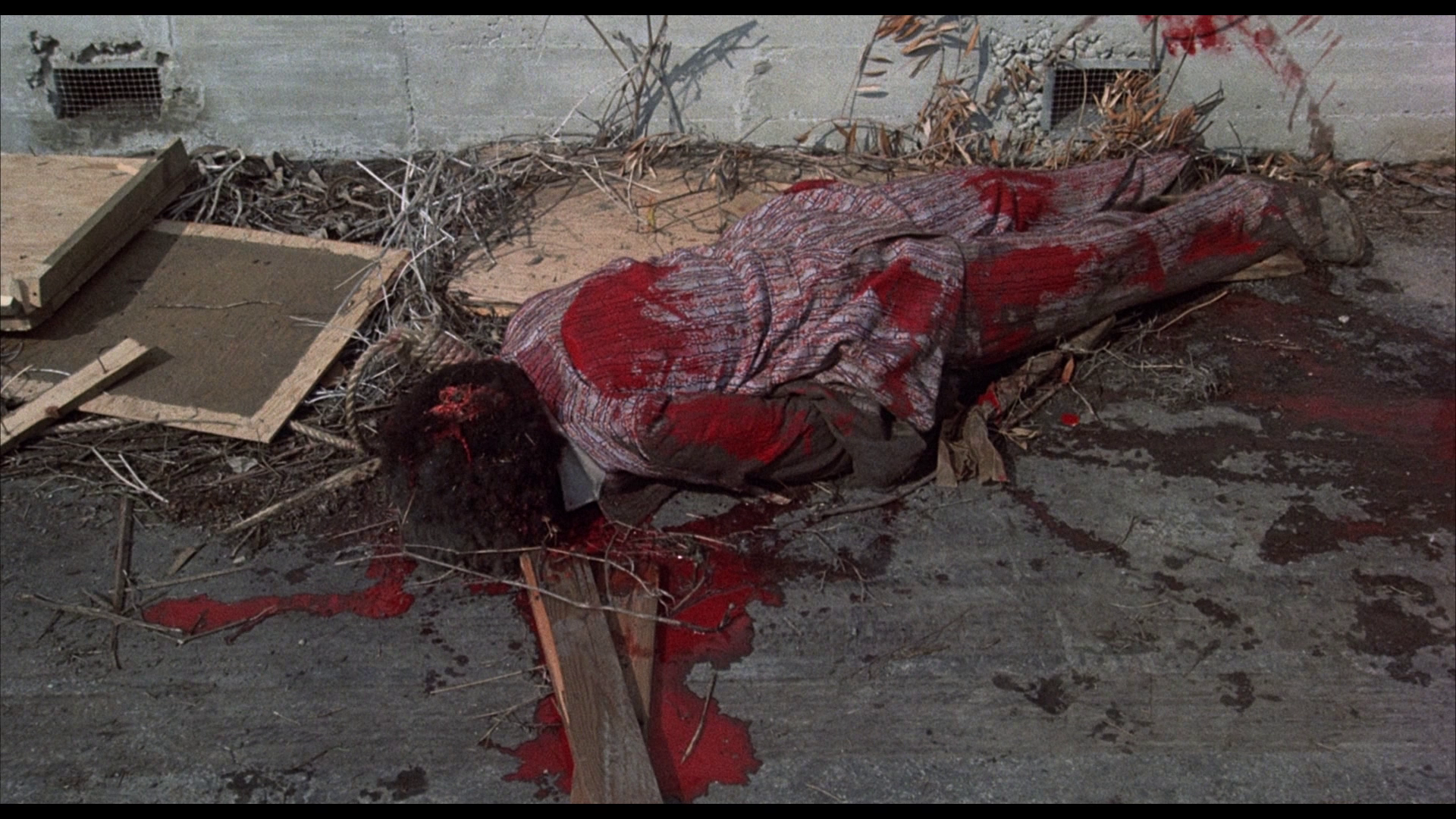

Carter’s corrupt partner arranges for Carter to suffer a beating for his refusal to go ‘on the take’. The beating, which puts Carter in the hospital, is administered by two of Vitroni’s hired thugs (one of whom is played by Sid Haig). Carter’s beating spurs Coffy on to further acts of revenge, and to achieve this she poses as an exotic prostitute to infiltrate the stable of pimp ‘King’ George (Robert DoQui). ‘King’ George sends Coffy to ‘servive’ Vitroni. When Coffy makes an attempt on Vitroni’s life, she is caught and, interrogated, frames ‘King’ George for the assassination attempt. In response, Vitroni sends his two hitmen to kill ‘King’ George: they tie a noose around his neck, Omar (Haig) declaring ‘This is how we lynch niggers’, before dragging ‘King’ George from their car. Meanwhile, Vitroni becomes aware of Coffy’s relationship with Brunswick. Vitroni holds Coffy captive. Arriving for a sit-down with Vitroni, Brunswick is made aware of the presence of Coffy and demonstrates his allegiance to Vitroni by demanding that Coffy be executed. Omar and his accomplice drive Coffy to a deserted location and prepare to kill her, making her death appear to be an overdose. However, pretending to offer herself to Omar Coffy manages to escape and returns to Vitroni’s house seeking vengeance.  Coffy is a ‘black’ film made by a predominantly white crew, and Hill has suggested that when the picture was made, American International Pictures ‘was very, very conscious of criticism in the media about not having black people behind the camera’ (Hill, quoted in Walker et al, 2009: 104). Hill claims that ‘we searched everywhere, and there were simply no black technicians available’, owing to the fact that the picture was a union film and ‘it was very difficult to get into the union and you had to have years and years of experience’ (ibid.: 104-5). This, of course, was something which black crew members struggled to gather owing to prejudice within the industry (and within society generally). However, Hill says that he hopes ‘the success of those films—with a general audience, not solely a black audience—contributed to the acceptance by audiences of black characters and black lifestyles in films’, gradually bringing ‘black characters and black lifestyles into mainstream films’ (ibid.: 105). Coffy is a ‘black’ film made by a predominantly white crew, and Hill has suggested that when the picture was made, American International Pictures ‘was very, very conscious of criticism in the media about not having black people behind the camera’ (Hill, quoted in Walker et al, 2009: 104). Hill claims that ‘we searched everywhere, and there were simply no black technicians available’, owing to the fact that the picture was a union film and ‘it was very difficult to get into the union and you had to have years and years of experience’ (ibid.: 104-5). This, of course, was something which black crew members struggled to gather owing to prejudice within the industry (and within society generally). However, Hill says that he hopes ‘the success of those films—with a general audience, not solely a black audience—contributed to the acceptance by audiences of black characters and black lifestyles in films’, gradually bringing ‘black characters and black lifestyles into mainstream films’ (ibid.: 105).

In Philosophy, Black Film, Film Noir, Dan Flory groups Coffy with Gordon Parks’ Shaft (1971), Gordon Parks Jr’s Super Fly (1972) and Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar (1973). All of these films, Flory argues, ‘use the techniques and themes of noir to tap into audience sympathies for violent, “bad” black male and female characters’ (Flory, 2008: 37). Although the opening sequence establishes the brutal violence of Coffy’s quest for revenge (she kills both dealers with a shotgun at point blank range), Coffy is established as a sympathetic character through her paid work as a nurse and her volunteer work in a clinic for children who are hooked on drugs. (When Coffy encounters Carter at the hospital where she works as a nurse, he asks her for a date, and she tells him ‘You won’t want to do what I’m doing tomorrow’; the next sequence depicts Coffy showing Carter around the clinic and introducing him to the children.)  Coffy herself engages with the morality of her actions, asking Carter if it may be considered right to kill someone who has strung out a child on dope. ‘What, to kill some poor pusher who’s only selling to get money to buy for himself?’, Carter asks, ‘What good would that do, Coffy? He’s only part of a chain that reaches all the way back to some poor farmer in Turkey or Vietnam. What would you do, kill all of ‘em?’ To this, Coffy answers, ‘Well, why not? [….] The law doesn’t do anything, because the law is in for a piece of the action’. Carter reminds Coffy that though there may be many corrupt policemen, he’s not one of them, telling her, ‘Not all of us. Not yet’. Later, Carter tells Coffy that ‘There’s plenty of good cops left. What we need is more support from the people’. For Dan Flory, ‘the moral ambiguity and pervasiveness of evil in Coffy makes it at least plausible to think of this film as much more noir than most critics have realized’: the story of Coffy, the film’s female protagonist, is one of ‘overwhelming defeat by overwhelmed corruption and personal betrayal’, something which Flory suggests was ‘slowly drained’ from Grier’s later films, beginning with Foxy Brown (ibid.). Coffy herself engages with the morality of her actions, asking Carter if it may be considered right to kill someone who has strung out a child on dope. ‘What, to kill some poor pusher who’s only selling to get money to buy for himself?’, Carter asks, ‘What good would that do, Coffy? He’s only part of a chain that reaches all the way back to some poor farmer in Turkey or Vietnam. What would you do, kill all of ‘em?’ To this, Coffy answers, ‘Well, why not? [….] The law doesn’t do anything, because the law is in for a piece of the action’. Carter reminds Coffy that though there may be many corrupt policemen, he’s not one of them, telling her, ‘Not all of us. Not yet’. Later, Carter tells Coffy that ‘There’s plenty of good cops left. What we need is more support from the people’. For Dan Flory, ‘the moral ambiguity and pervasiveness of evil in Coffy makes it at least plausible to think of this film as much more noir than most critics have realized’: the story of Coffy, the film’s female protagonist, is one of ‘overwhelming defeat by overwhelmed corruption and personal betrayal’, something which Flory suggests was ‘slowly drained’ from Grier’s later films, beginning with Foxy Brown (ibid.).

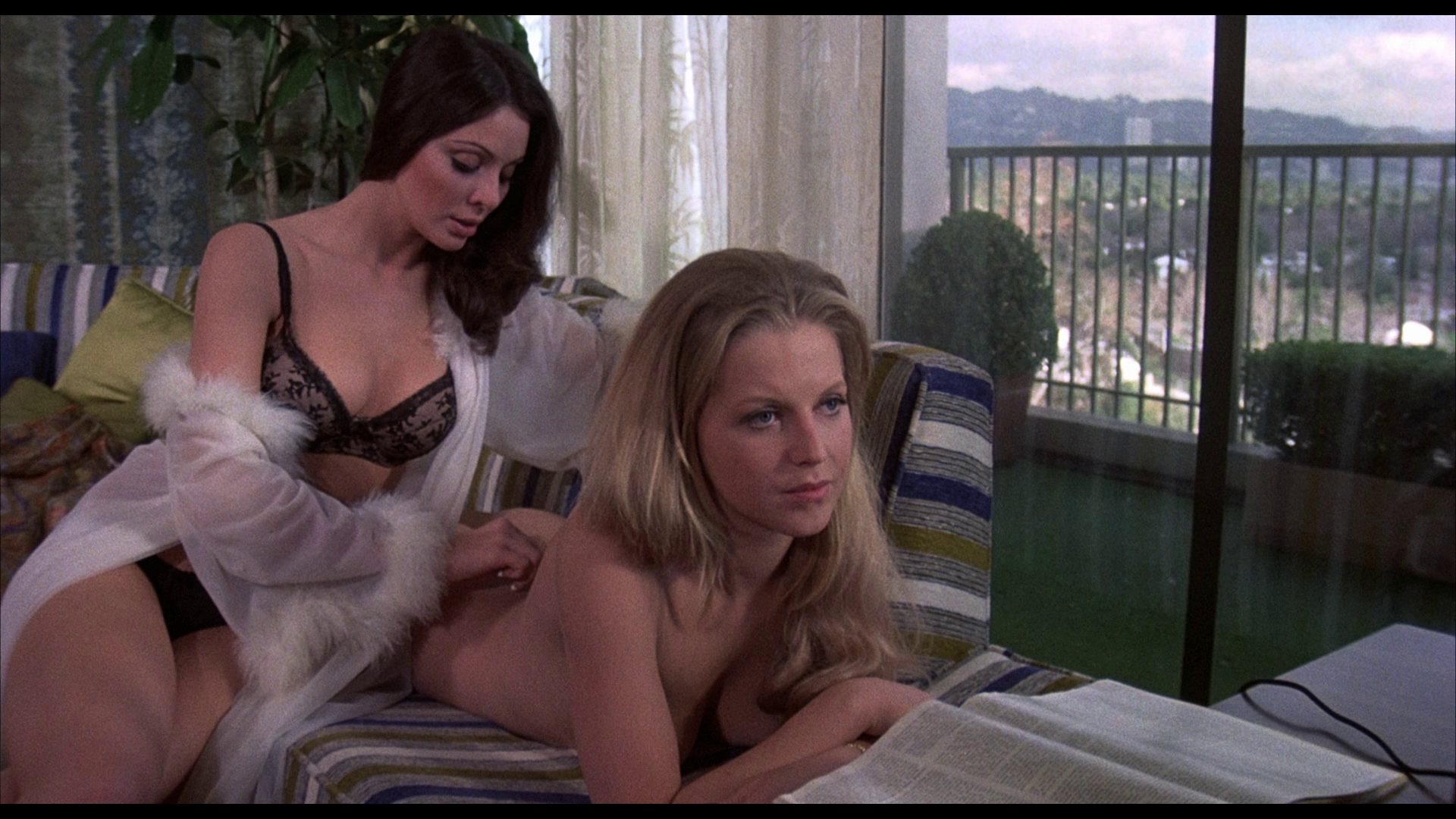

Sharing Coffy’s perspective for the bulk of its running time (with a small handful of scenes told from outside Coffy’s perspective), the film builds a convincing interior world for its protagonist through Hill’s use of non-linear editing, introducing very brief flashbacks whilst Coffy is driving, etc, to reinforce the importance of her need to seek revenge for her sister. The film’s revenge plot allows Hill to focus subtly on the impact of drugs on black subcultures and consider the extent to which this is legitimated by political corruption. In Hooked in Film: Substance Abuse on the Big Screen, John Markert suggests that Coffy’s focus on the ‘heroin thread is quite strong’ throughout the narrative, ‘so the viewer never loses sight of the harm it causes within the black community, and who’s at fault: corrupt (white) police, and even the aspiring black politician with whom Coffy is involved, who spouts the right words among black voters but is as corrupt as “the man”’ (Markert, 2013: 105). The film offsets extravagant action and kitsch 1970s fashions with a quite impactful grittiness. Coffy was produced as a response to Cleopatra Jones. The script that would form the basis for Cleopatra Jones was written by Max Julien and presented by producer William Tennant to Larry Gordon, then-head of production at AIP. However, Tennant backed out of his agreement with Gordon after being offered more money by Warner Brothers. Irritated at Tennant’s betrayal, Gordon ‘set out to scoop [Cleopatra] Jones by making his own action film featuring a black female protagonist’, but instead ‘of a law-abiding heroine’ Gordon decided that the film should focus on ‘a black female vigilante’ (Lawrence, op cit.: np). Given to Jack Hill to develop, Gordon’s project evolved into Coffy; the completed film was released three weeks before Warners’ Cleopatra Jones. Mia Mask argues that for Pam Grier, Coffy ‘served as the bridge from sexploitation to Blaxploitation’, offering Grier her first starring role (Mask, 2009: 89). Prior to Coffy, Grier’s screen roles had been limited to secondary roles in films such as the ‘women in prison’ pictures The Big Doll House (Jack Hill, 1971), Women in Cages (Gerardo de Leon, 1971) and The Big Bird Cage (Jack Hill, 1972). In these films, Grier (along with the rest of the female cast) had been utterly objectified, with the focus being on her characters’ sexual exploitation. In Coffy, by contrast, Grier’s character is fully aware of her own sexuality and uses it to entrap the men she wishes to punish for her sister’s predicament. Dominique Mainon and James Ursini note that Grier’s Coffy ‘uses her sexual allure, as well as her physical strength and acute intelligence, to defeat her enemies’ (Mainon & Ursini, 2006: 222). The character ‘gains the trust of the male characters […] by using the sexual stereotypes they project on her, and then reverses the stereotype, to the consternation of the unwitting character’ (ibid.).  Coffy’s sexuality is also on display in her relationship with Howard Brunswick. During an early sequence, they make love; as they do so, Hill uses quick cutaways to the murder Coffy commits in the film’s opening sequence, suggesting that Coffy is flashing back to this during her intimate moments with Howard. This perhaps foreshadows the later revelation that Brunswick, who is planning on running for Congress and during media appearances makes all the right noises about wanting to stop the destruction of black communities by the influx of illegal narcotics, is corrupt and in league with the mob boss and drug peddler Vitroni. Coffy’s sexuality is also on display in her relationship with Howard Brunswick. During an early sequence, they make love; as they do so, Hill uses quick cutaways to the murder Coffy commits in the film’s opening sequence, suggesting that Coffy is flashing back to this during her intimate moments with Howard. This perhaps foreshadows the later revelation that Brunswick, who is planning on running for Congress and during media appearances makes all the right noises about wanting to stop the destruction of black communities by the influx of illegal narcotics, is corrupt and in league with the mob boss and drug peddler Vitroni.

Grier’s Coffy is our figure of identification within the film, the only person apparently capable of achieving the aims Brunswick claims to desire (ie, putting a stop to the influx of drugs on the city’s streets) within a context in which the police and politicians are either corrupt or incapable of doing anything. Her actions drive the narrative. However, much as she constructs herself as an object of desire for her ‘targets’, she is also objectified by Hill’s camera, frequently placed in scenes which depict Coffy in various stages of undress. Novotny Lawrence suggests that though the film gives audiences a black woman who is strong and independent, ‘it is important to note that the film is an AIP production’ and therefore ‘contains many of the titillating elements of the company’s previous exploitation fare’ (Lawrence, op cit.: np). As a consequence, Coffy’s status ‘as an action heroine is complicated by her construction as a sex object’ (ibid.). During the scene in which she makes love to Howard, given that we have seen Howard conversing with Vitroni (in a scene from outside Coffy’s perspective) and we are aware that Coffy has already used her sexuality to create a ‘honey trap’ for the drug dealers in the opening sequence, we initially might question whether or not Coffy is enacting a ‘performance’ and staging a similar trap for Howard. (This is compounded by the fact that Coffy’s former paramour Carter seems like a better match for her romantically.) However, it gradually becomes clear that Coffy cares for Howard deeply, which makes his offhand dismissal of her towards the end of the film (in which, after Coffy has been captured by Vitroni, Howard tries to save his skin by giving the order for Coffy to be killed) all the more powerful.  Vitroni’s thugs are brutal and Omar in particular is not averse to hurling racial epithets at his victims. The murder of ‘King’ George is a grotesque parody of a lynching, with Omar and his accomplice tying a noose around George’s neck and dragging him from their car. After they have killed ‘King’ George, Omar approaches the visibly shaken Studs, George’s chauffeur, and tells him matter-of-factly, ‘You’re going to need a job soon. You come to us. You find out we’re not bad people’. Still, despite their viciousness, these men aren’t really the film’s ‘real’ villain, and neither is Vitroni. Howard is the true villain of the piece, a man who, running for Congress, betrays the principles for which he claims to fight; his betrayal of Coffy is a metaphor for Howard’s betrayal of the people for whom he claims to stand. During a media interview, Howard rails against the drug trade and asserts, ‘It’s this vicious combination of big business and government which has kept our sisters prostitute [sic] and our brothers dope peddlers’, adding that ‘This whole thing [the drug trade] becomes a vicious attempt on part of the white power structure to exploit our black men and women in this society’. However, behind closed doors Howard is a part of this corruption, meeting with mob bosses like Vitroni and corrupt policemen. Vitroni’s thugs are brutal and Omar in particular is not averse to hurling racial epithets at his victims. The murder of ‘King’ George is a grotesque parody of a lynching, with Omar and his accomplice tying a noose around George’s neck and dragging him from their car. After they have killed ‘King’ George, Omar approaches the visibly shaken Studs, George’s chauffeur, and tells him matter-of-factly, ‘You’re going to need a job soon. You come to us. You find out we’re not bad people’. Still, despite their viciousness, these men aren’t really the film’s ‘real’ villain, and neither is Vitroni. Howard is the true villain of the piece, a man who, running for Congress, betrays the principles for which he claims to fight; his betrayal of Coffy is a metaphor for Howard’s betrayal of the people for whom he claims to stand. During a media interview, Howard rails against the drug trade and asserts, ‘It’s this vicious combination of big business and government which has kept our sisters prostitute [sic] and our brothers dope peddlers’, adding that ‘This whole thing [the drug trade] becomes a vicious attempt on part of the white power structure to exploit our black men and women in this society’. However, behind closed doors Howard is a part of this corruption, meeting with mob bosses like Vitroni and corrupt policemen.

Howard is motivated solely by self-interest and will sacrifice his community and rhetoric on the altar of money. ‘Black, brown or yellow, I’m in it for the green’, Howard asserts before giving the order to have Coffy executed. When Coffy, having dispatched Vitroni’s henchmen, returns to confront Howard, he attempts to use his politician’s rhetoric to escape his punishment: ‘You think if I weren’t mixed up in the rackets, there wouldn’t be any rackets’, he reasons, ‘Wherever there’s a need somebody comes along to fill it. Black people want dope; and brown people want dope. And as long as people are deprived of a decent life, they’re gonna want something to just feel plain good with. And nothing’s gonna change that, except money and power’. ‘You’re just sellin’ out to the white gangsters and businessmen’, Coffy says, ‘You’re worse than they are’. ‘Maybe I have done a few bad things’, Howard concedes, ‘But that’s the way the world is today. Sometimes you have to do a few little wrong things to do one big right thing’. Ultimately, though commercially successful, Coffy proved to be a controversial film, with some commentators suggesting that the picture’s depiction of a strong black woman should be celebrated as empowering, especially ‘alongside roles that extolled the mammy, jezebel, and tragic mulatto’, and others arguing that the film’s focus on Coffy’s sexuality (and Grier’s body) was problematic (Banks, 2008: 79). Ingrid Banks suggests that some of the more vociferous critics of Grier’s films perhaps ‘overlooked Coffy and Foxy Brown as protectors of black communities […] because portrayals of black women as superwomen in film reinforced the belief that “strong” black women were actually the black community’s downfall, because such women laid the foundation for the emasculation of black men’ (ibid.: 80). Thus Coffy is both an ‘empowering and intimidating’ figure (ibid.).

Video

Taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered BD, Coffy is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered BD, Coffy is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The presentation seems to be based on an older master, probably that used for the earlier DVD releases. However, it’s a fine, perfectly acceptable presentation. A natural level of film grain is present, ensuring the image has an organic, film-like appearance. The opening club scene (with its vivid use of primary colours) and the night-time drive that follow it evidence the good colour consistency and contrast that is exhibited throughout the rest of the film. (Though it has to be said that some of the blacks are ‘crushed’.) There’s a pleasing level of detail within the image and a sense of depth to it but there’s a ‘flatness’ to the original photography (with action taking place on a mostly very ‘flat’ plane) and restricted compositions, probably owing to a rushed schedule and the low-budget nature of the production, that means Coffy, for most of its running time, has the look of a 1970s television show. NB. Larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The disc contains a lossless LPCM 1.0 mono track. The dynamic range of this track is evidenced from the get-go in the burst of funky music which accompanies the opening nightclub sequence. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes a good range of contextual material, including: - a commentary with director Jack Hill. In this commentary, the same commentary included on the R1 DVD release of Coffy, Hill talks about the genesis and production of the film and its lasting legacy. - an interview with Jack Hill entitled ‘A Taste of Coffy’ (18:49). This new interview with Hill focuses on some of the same issues covered in the commentary but Hill’s points here are more concise. Hill talks about the film’s financing and his relationship with the blaxploitation cycle. He also discusses some of the techniques used in the production of the film and the picture’s ongoing cult following. - an interview with Pam Grier, ‘The Baddest Chick in Town!’ (17:38). This fascinating interview with Grier examines the film in relation to its social context. Grier is an amiable, insightful interviewee. Grier also talks about her working relationship with Jack Hill. - a video essay by Mikel J Koven, ‘Blaxploitation!’ (28:56). Koven’s video essay offers a discussion of the blaxploitation cycle of films and the ways in which it developed in response to the fallout of the Civil Rights era. Koven offers some sometimes provocative interpretations of specific films - the film’s original trailer (2:01). - a stills gallery.

Overall

Unlike the bulk of blaxploitation films with their New York settings (‘Harlem is the capital of every ghetto town’, sings Bobby Womack in the title song for Barry Shear’s searing 1972 picture Across 110th Street), Coffy (along with Foxy Brown) foregrounds its West Coast setting. It’s a much darker film than Foxy Brown and is altogether closer in spirit to a film noir than some of the more action-oriented examples of the blaxploitation cycle. (In that sense, although ostensibly very different, it has much in common with Barry Shear’s aforementioned Across 110th Street.) Coffy is an important film in many respects, not least of which is its representation of a strong black woman as the film’s protagonist. Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of the film, though based on an older master, is very good and contains some excellent contextual material, especially the new interview with Grier. Unlike the bulk of blaxploitation films with their New York settings (‘Harlem is the capital of every ghetto town’, sings Bobby Womack in the title song for Barry Shear’s searing 1972 picture Across 110th Street), Coffy (along with Foxy Brown) foregrounds its West Coast setting. It’s a much darker film than Foxy Brown and is altogether closer in spirit to a film noir than some of the more action-oriented examples of the blaxploitation cycle. (In that sense, although ostensibly very different, it has much in common with Barry Shear’s aforementioned Across 110th Street.) Coffy is an important film in many respects, not least of which is its representation of a strong black woman as the film’s protagonist. Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of the film, though based on an older master, is very good and contains some excellent contextual material, especially the new interview with Grier.

References Banks, Ingrid, 2008: ‘Women in Film’. In: Boyd, Todd (ed), 2008: African Americans and Popular Culture. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers: 67-88 Flory, Dan, 2008: Philosophy, Black Film, Film Noir. Pennsylvania State University Press Lawrence, Novotny, 2007: Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s: Blackness and Genre. London: Routledge Mainon, Dominique & Ursini, James, 2006: The Modern Amazons: Warrior Women On-Screen. New Jersey: Limelight Editions Markert, John, 2013: Hooked in Film: Substance Abuse on the Big Screen. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Mask, Mia, 2009: Divas on Screen: Black Women in American Film. University of Illinois press Walker, David et al, 2009: Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|