|

|

Retaliation AKA Shima wa moratta (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th May 2015). |

|

The Film

Retaliation AKA Territorial Dispute AKA Turf War (Hasebe Yasuharu, 1969) Retaliation AKA Territorial Dispute AKA Turf War (Hasebe Yasuharu, 1969)

Nikkatsu’s production of youth-oriented mokukuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures began in 1956 with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun. The films were considered ‘borderless’ in the sense that they drew from American and European cinema, taking something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixing it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. One of the closest corollaries to Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless action’ films is perhaps the work of Jean-Pierre Melville, the French filmmaker who with films such as Le samourai (1967) and Le cercle rouge (1970) married the independence and auteurist experimentation of the French nouvelle vague with the iconography (and narrative conventions) of the Hollywood gangster film. Nikkatsu’s mokukuseki akushon films featured individualistic heroes, often gangsters or policemen, who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes shot in film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting. This was in stark contrast to earlier yakuza films: the yakuza had featured in Japanese cinema since the silent era, but usually in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). In earlier yakuza films, the villains were often Westernised, and in contrast with these Westernised characters the moral code of the yakuza would usually be depicted in a positive light. Nikkatsu’s action films, with their contemporary urban settings and their morally-conflicted and Westernised heroes (rather than villains), were in stark contrast with these earlier yakuza pictures. In comparison with the earlier yakuza films with a period setting, the Nikkatsu films of the 1960s often featured an implicit critique of the code of the yakuza that was buried within an exploration of inter-generational conflict, with the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans frequently depictured as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mokukuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182).  As the 1960s progressed, Nikkatsu’s action films became increasingly moody, some of them evolving into what were labeled as mudo akushon (‘mood action’) films. As cinema audiences dwindled during the late-1960s, these gave way to a new subgenre of nyu akushon (‘new action’) films, which were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were morally-ambiguous. In the 1970s, these would be supplanted by the jitsuroku films. The jitsuroku pictures used documentary filmmaking techniques (handheld camerawork, abrupt editing rhythms) and depicted the yakuza as little more than street thugs motivated solely by self-interest. (Fukasaku Kinji’s 1973 film Battles Without Honour and Humanity is often cited as one of the earliest examples of the jitsuroku subgenre.) During the same era, as cinema audiences continued to decline, Nikkatsu turned its attention away from the gangster films and youth comedies that had been its forte since the mid-1950s and began to focus on the production of Roman Porno films – erotic pictures that subsequently came to define the Nikkatsu ‘brand’ for many years to come. As the 1960s progressed, Nikkatsu’s action films became increasingly moody, some of them evolving into what were labeled as mudo akushon (‘mood action’) films. As cinema audiences dwindled during the late-1960s, these gave way to a new subgenre of nyu akushon (‘new action’) films, which were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were morally-ambiguous. In the 1970s, these would be supplanted by the jitsuroku films. The jitsuroku pictures used documentary filmmaking techniques (handheld camerawork, abrupt editing rhythms) and depicted the yakuza as little more than street thugs motivated solely by self-interest. (Fukasaku Kinji’s 1973 film Battles Without Honour and Humanity is often cited as one of the earliest examples of the jitsuroku subgenre.) During the same era, as cinema audiences continued to decline, Nikkatsu turned its attention away from the gangster films and youth comedies that had been its forte since the mid-1950s and began to focus on the production of Roman Porno films – erotic pictures that subsequently came to define the Nikkatsu ‘brand’ for many years to come.

In the late-1960s, some directors within the Nikkatsu ‘stable’ demonstrated a strong sense of invention: Suzuki Seijun is possibly the most famous example, given the outrageous experimentation within his anarchic 1967 picture Branded to Kill which led to him being fired by Nikkatsu. Suzuki was hired to direct the film at the last minute and turned in a picture that, to Nikkatsu’s bosses, was deliberately ‘incomprehensible’ (Sharp, op cit.: 182). Branded to Kill may be considered as a subversive self-parody of the mokukuseki akushon pictures, and when Suzuki struck back by suing Nikkatsu, leading to him being effectively blacklisted for the next ten years, he consolidated his position as somewhat of a countercultural figure. Although less outrageously subversive than Branded to Kill (and shot in vivid colour, in comparison with Branded to Kill’s high contrast monochrome photography), Hasebe Yasuharu’s directorial debut Black Tight Killers was no less playful, featuring a hero (Kobayashi Akira) who is hunted down by a troupe of go-go dancers-cum-assassins whose deadly arsenal includes LPs and bubblegum.  Arrow have recently released Hasebe’s third film, Massacre Gun (1967), on Blu-ray (read our review of that release here). The film under discussion, Retaliation (1969), was Hasebe’s fourth feature as a director. Shot quickly and cheaply, Hasebe’s films show a confidence of style – which is perhaps unsurprising, given that in his first six or seven years working as an assistant director for Nikkatsu, Hasebe worked on between fifty and sixty films (Hasebe, quoted in Desjardins, 2005: 131). Once he became a director, Hasebe was working on four or five films per year, with most of these films made ‘on a 30-day cycle’ (Hasebe, quoted in ibid.). Arrow have recently released Hasebe’s third film, Massacre Gun (1967), on Blu-ray (read our review of that release here). The film under discussion, Retaliation (1969), was Hasebe’s fourth feature as a director. Shot quickly and cheaply, Hasebe’s films show a confidence of style – which is perhaps unsurprising, given that in his first six or seven years working as an assistant director for Nikkatsu, Hasebe worked on between fifty and sixty films (Hasebe, quoted in Desjardins, 2005: 131). Once he became a director, Hasebe was working on four or five films per year, with most of these films made ‘on a 30-day cycle’ (Hasebe, quoted in ibid.).

Hasebe has cited John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Don Siegel’s The Killers (1963) as among his favourite films, and it’s easy to see the influence of the American hard-boiled style in Hasebe’s work (Hasebe, quoted in Desjardins, op cit.: 131). Alexander Jacoby has described Hasebe’s films as ‘high on camp and low in intelligence, a combination that has earned him a cult reputation in some quarters’ (Jacoby, 2008: 1965). However, it’s perhaps fairer to say that Hasebe’s career oscillated between the camp delights of films like Black Tight Killers and the gritty, almost nihilistic sensibility evidenced in Massacre Gun, Retaliation and Bloody Territories (1969); sometimes Hasebe would combine these two approaches within a single film, as is the case in his Roman Porno films Assault! Jack the Ripper (1976) and Rape! 13th Hour (1977). Chris Desjardins has described Hasebe’s late-1960s films, including Massacre Gun and Retaliation, as ‘contemporary yakuza films, all caught in that gradually more hard-edged swing towards realism as the decade ended’ (Desjardins, op cit.: 127). Like many of Nikkatsu’s gangster films of the era, Hasebe’s Massacre Gun and Retaliation ‘featured gangster anti-heroes but ones who were possessed of some redeemable quality such as honor and loyalty, and were, alas, distressingly outnumbered by legions of corporate yakuza’ (ibid.). Retaliation is such a tale, focusing on an honourable yakuza who finds himself set against far less scrupulous corporate gangsters who seek to rob a group of farmers of their land. The film begins as yakuza Shagae Jiro (Kobayashi Akira) is released from prison having served eight years for killing rival gangster Hino Katsuo. Awaiting Jiro is Hino’s brother (Sishido Jô), who plans to kill Jiro. (‘I’ve spent eight years in jail. That’s payment enough’, Jiro tells Hino, to which Hino replies, ‘I’ve waited eight years for this day… to kill you’.) However, the ensuant fight between Jiro and Hino is broken up by a young woman, Hino’s lover (‘If you kill him, what will happen to us?’, she asks Hino). As Jiro walks away, Hino’s promise of revenge frustrated, Hino threatens him: ‘You’re mine. Don’t forget it’.  Jiro visits the elderly head of his clan, the Ichimonji family, but finds that the boss of the clan is racked with guilt: ‘You gave up your freedom to save the Ichimonji family’, he tells Jiro, ‘but I’ve let it go to ruin. I’m ashamed of myself’. During Jiro’s time in prison, it seems, the Ichimonji family has lost much of its territory to the Hazama clan. Jiro visits the head of the Hazama family, who asks Jiro to work for him in taking over Takagawa City. Takagawa is set for redevelopment and investment from big business, but Jiro must persuade the ‘few minor gangs’ who control the territory within Takagawa ‘to consolidate’ their interests and buy the land from the farmers that own it, so that they mey sell it on to the factory owners at a considerable profit. Jiro asks why the Hazama clan should trust him with this responsibility. ‘I know you’re capable’, is the reply he receives. Jiro visits the elderly head of his clan, the Ichimonji family, but finds that the boss of the clan is racked with guilt: ‘You gave up your freedom to save the Ichimonji family’, he tells Jiro, ‘but I’ve let it go to ruin. I’m ashamed of myself’. During Jiro’s time in prison, it seems, the Ichimonji family has lost much of its territory to the Hazama clan. Jiro visits the head of the Hazama family, who asks Jiro to work for him in taking over Takagawa City. Takagawa is set for redevelopment and investment from big business, but Jiro must persuade the ‘few minor gangs’ who control the territory within Takagawa ‘to consolidate’ their interests and buy the land from the farmers that own it, so that they mey sell it on to the factory owners at a considerable profit. Jiro asks why the Hazama clan should trust him with this responsibility. ‘I know you’re capable’, is the reply he receives.

Jiro accepts the job after discussing it with the head of the Ichimonji family, who sees it as a chance for the Ichimonji clan to redeem itself. Jiro is introduced by the Hazama family to his ‘gang’, whom Jiro describes as ‘A bunch of card cheats, warblers, and an actor’: Naruso, Iizuku, Nakatsu and Shinjo. Jiro is also told that he must work with Hino. An unhappy Hino must set aside his grudge against Jiro in order to achieve the Hazama family’s aim: control of the territories within Takagawa City. Takagawa City is controlled by two gangs: the Tono gang, who have controlled much of Takagawa for five generations, and who are sympathetic towards the farmers who own the land within the district; and the Aoba gang, led by the sadistic Kitakata (Hayama Ryôji). The Aoba gang aim to persuade the local farmers to sell their land cheaply to the Aoba group, who will then pass it on at a steep profit to the factory owners who want to build there. Arriving in Takagawa, Jiro and his gang witness the Aoba thugs abducting a young woman, Saeko (Kaji Meiko), before sexually assaulting her in the back of a car and dumping her by the roadside outside her family home. The Aoba gang threaten Saeko’s father, one of the farmers, with shame in an attempt to force him into selling his land to them. However, the Aobo gang members are confronted by members of the Tono family: ‘The Tono family don’t play dirty’, they assert, ‘We believe in the old law: “Protect those who work the land”’. Jiro uses his gang members to infiltrate the Tono and Aoba gangs, pushing the two rival groups into conflict as a means of weakening them. The plot works: after Shinjo provokes a fight at one of the Aoba gang’s gambling dens, the factory owners withdraw their support for the Aoba clan, telling them, ‘After a scandal like that, no farmer will sell to you. We can’t be getting involved with gangsters […..] [W]e wash our hands of you’. With the Aoba clan’s position weakened considerably, Jiro approaches the farmers and asks them to sell their land. However, the farmers ask him, ‘If we sell our land, how will we live?’ Jiro becomes increasingly sympathetic towards the farmers, realising how they are connected to the past and becoming cognisant of the importance of farming for the community. However, the Aoba gang soon retaliate by kidnapping Shinjo and torturing him, beating him and burning his face with lit cigarettes. When Shinjo’s corpse is found, Jiro strikes back by having the higher-ranking members of the Aoba clan attacked. Eventually, all-out war breaks out between the Tono and Aoba clans. Jiro’s defence of the farmers earns him the trust and respect of Hino, but Jiro and his group discover that the Hazama clan are equally as set on exploiting the farmers as the Aoba family – and as the narrative progresses, the Hazama gang join forces with the Aoba clan against the farmers and their ostensible protectors: Jiro, Hino and the others.  Reflecting a trend that would come to dominate both Nikkatsu’s later Roman Porno films and the jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s, Retaliation contains an emphasis on sexual violence as a badge of the deviance of the Aoba clan. When Jiro and his group first arrive in Takagawa City, they see members of the Aoba clan abducting Saeko and subjecting her to a sexual assault in the back of their car, threatening her with rape. In a later scene, a prostitute’s client is seen threatening her with sexual violence, in a brothel that seems to be managed by the Aoba clan. The prostitute cries out and resists; the client flees. However, Kitakata intervenes. ‘The man’s a sadist’, the prostitute weeps. ‘He pays you well, so you do whatever he wants’, Kitakata tells her unsympathetically, before binding her. ‘See, that’s what he likes’, Kitakata tells her, ‘Nothing to get upset about, eh? Do as you’re told. Next time I won’t be so gentle’. Reflecting a trend that would come to dominate both Nikkatsu’s later Roman Porno films and the jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s, Retaliation contains an emphasis on sexual violence as a badge of the deviance of the Aoba clan. When Jiro and his group first arrive in Takagawa City, they see members of the Aoba clan abducting Saeko and subjecting her to a sexual assault in the back of their car, threatening her with rape. In a later scene, a prostitute’s client is seen threatening her with sexual violence, in a brothel that seems to be managed by the Aoba clan. The prostitute cries out and resists; the client flees. However, Kitakata intervenes. ‘The man’s a sadist’, the prostitute weeps. ‘He pays you well, so you do whatever he wants’, Kitakata tells her unsympathetically, before binding her. ‘See, that’s what he likes’, Kitakata tells her, ‘Nothing to get upset about, eh? Do as you’re told. Next time I won’t be so gentle’.

Throughout the film, the old traditions (symbolised by farming, with its connection to the past) are placed in conflict with new cutthroat business practices. (In some ways, the film is a reworking of the basic narrative within Kurosawa Akira’s acknowledged classic Seven Samurai, 1954, with Jiro and his gang fulfilling a similar narrative function to the seven ronin within Kurosawa’s film.) Retaliation offers what is almost a deliberate subversion of the traditional paradigms of period-set yakuza films (of the pre-mokukuseki akushon era), in which the yakuza were depicted as heroic protectors of farmers (the ‘old law’ to which the Tono gang refer: ‘Protect those who work on the land’). Early in the film, Jiro is told that ‘Old style gangsters can’t compete against modern methods’. ‘What methods?’, Jiro asks: ‘They buy re-zoned land cheap from the local farmers. Then they sell it at a profit to the factory owners’. Here, the modern-day yakuza are represented through the unscrupulous Aoba and Hazama gangs: dressed in suits and using the language of business, the latter are more outwardly ‘civilised’, whereas the members of the Aoba clan are more openly thug-like, threatening women with sexual violence and hiding out in gambling dens. However, both the Hazama and Aoba clans work together to essentially rob the famers of their land, and both yakuza families are like vultures circling the farming community, which seems doomed to die and its land be swallowed up for use by factories. The boss of the Hazama family tells Jiro, referring to Takagawa City, that change is inevitable: ‘It’s a boom town. A big factory will be built there. It’s new and it’s got promise’. To do this, the head of the Hazama clan says, Jiro must try to persuade the ‘few minor gangs there’ to ‘consolidate’ their interests.  At one point, before his change of heart towards the Hazama clan’s business practices, Jiro arranges a sit-down with the farmers and tries to persuade them to sell their land, telling them simply that, ‘You have to accept that’s how business works’. Shortly afterwards, Saeko asks him, ‘But what will happen to use all? Once a farmer sells his land, he has nothing’. ‘As times change, a new lifestyle will emerge’, Jiro says optimistically. ‘I hope so’, Saeko acknowledges, ‘But farmers hate change. The land payments are a one-time thing. But a farm produces for years, for centuries’. Saeko tells Jiro that the area ‘was once a peaceful village, but that’s all changed’. However, she asserts, ‘a farmer’s love of the land doesn’t disappear’. At one point, before his change of heart towards the Hazama clan’s business practices, Jiro arranges a sit-down with the farmers and tries to persuade them to sell their land, telling them simply that, ‘You have to accept that’s how business works’. Shortly afterwards, Saeko asks him, ‘But what will happen to use all? Once a farmer sells his land, he has nothing’. ‘As times change, a new lifestyle will emerge’, Jiro says optimistically. ‘I hope so’, Saeko acknowledges, ‘But farmers hate change. The land payments are a one-time thing. But a farm produces for years, for centuries’. Saeko tells Jiro that the area ‘was once a peaceful village, but that’s all changed’. However, she asserts, ‘a farmer’s love of the land doesn’t disappear’.

Eventually, Jiro comes to recognise the importance of the land for the farmers, both as a way of life and their only means of sustaining their independence, and in terms of its symbolic function as a through-line connecting the past and the future. However, although sympathetic towards the farmers, Jiro accepts the inevitability of change and tries to broker the best deal possible for the farmers. ‘Even if we don’t run it as before’, Jiro tells his don, referring to the Ichimonji family, ‘we’ll always be family. We yakuza have to change with the times: it’s inevitable’. Jiro’s attempts to help the farmers are ultimately sabotaged by the Hazama clan, who plan to ‘get rid of the farmers’ once the deal to sell their land has been brokered – an act for which they enlist the services of the Aoba gang. ‘That’s not what we agreed’, Jiro asserts angrily. Angry over the Hazama group’s betrayal of the farmers, Jiro confronts the head of the Hazama clan, telling him, ‘I won’t betray my men who died’. Commanded to apologise, Jiro refuses. His adherence to his principles earns him the respect of Hino, who puts aside his prior grievance with Jiro in order to aid him in his quest to protect the farmers from being exploited by the Hazama and Aoba gangs. (‘I’ve taken a liking to you. Who cares if I die?’, Hino tells Jiro.) The film is uncut and runs for 95:00 mins.

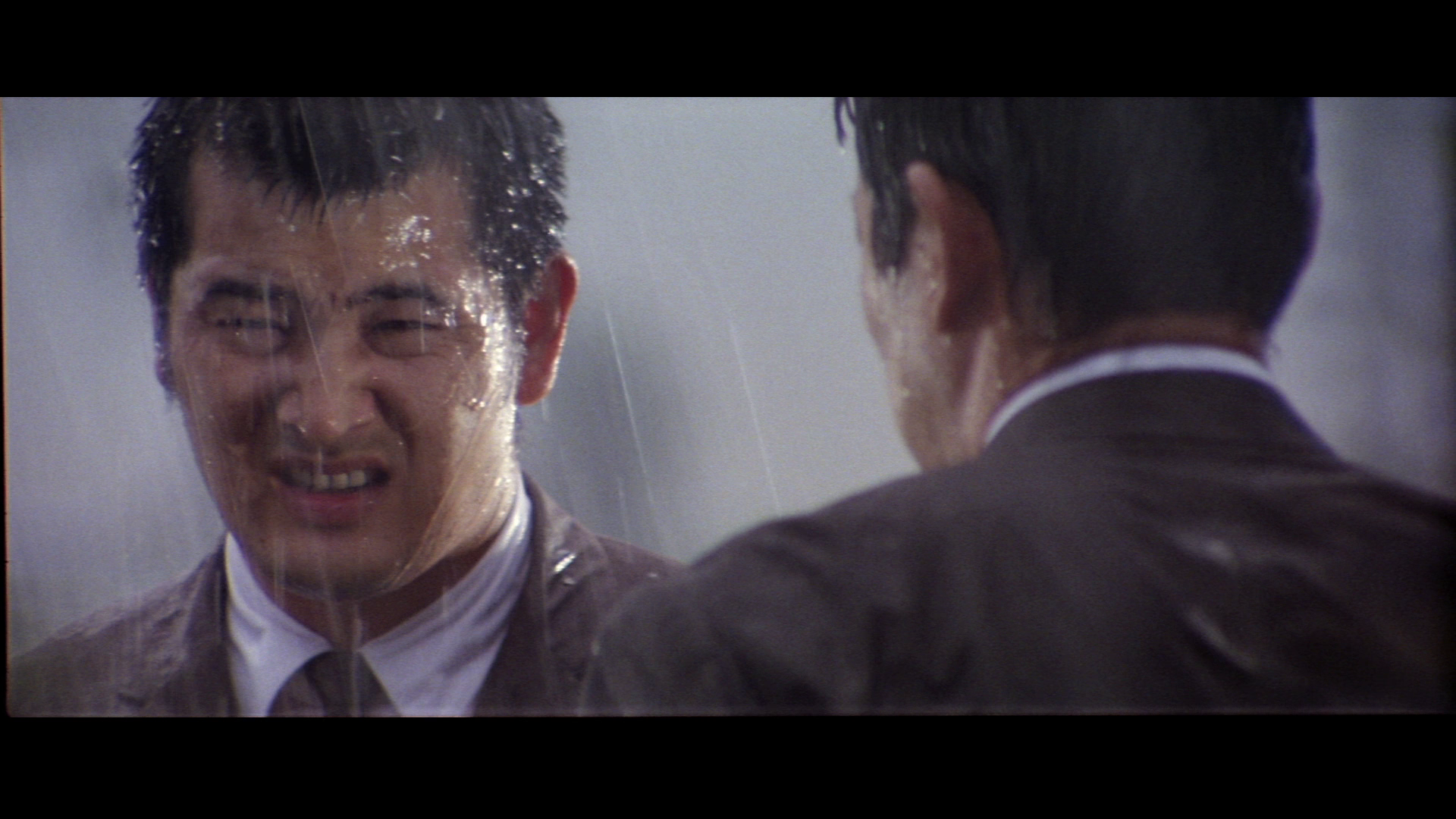

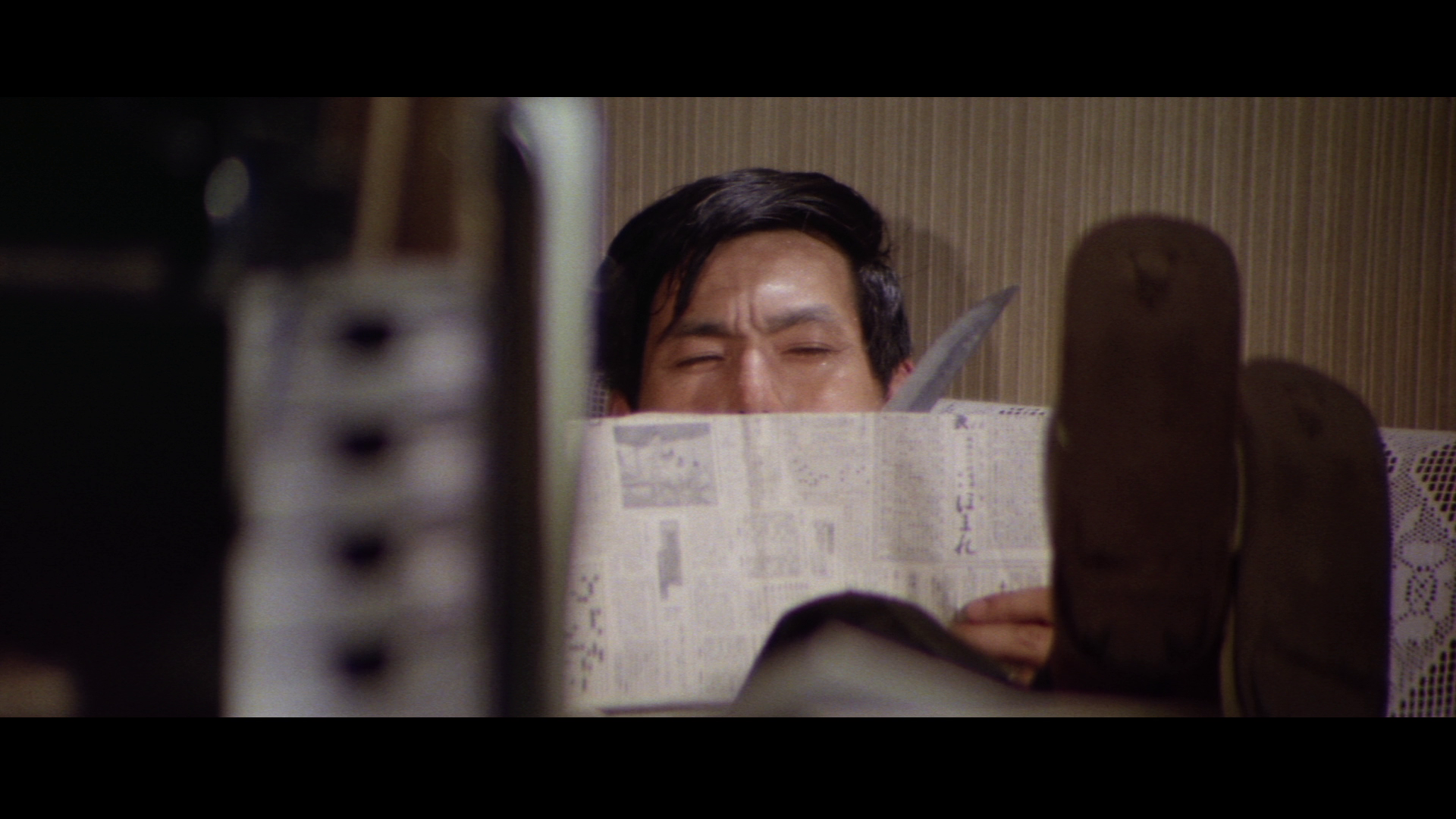

Video

The 1080p presentation of Retaliation takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, and the presentation uses the AVC codec.  With its almost documentary-like colour photography (which makes strong use of voyeuristic telephoto lenses) and its focus on backbiting within yakuza clans, Retaliation sits somewhere between the ‘borderless action’ films of the 1960s and the jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s. The film has a starkly different ‘look’ to Hasebe’s Massacre Gun; Chris Desjardins has said that Retaliation is shot by Hasebe ‘as if eavesdropping on many scenes’ (Desjardins, op cit.: 127). The photography contains some interesting compositions. From the opening sequence depicting Jiro’s release from prison, characters are often framed in long shot via telescopic lenses which flatten perspective, the foreground of the shot cluttered with objects (eg, blades of grass) that are out of focus, making the shots feel almost voyeuristic in nature. On top of this, in a number of sequences Hasebe uses zoom lenses, operating the zoom to track in on characters in the distance, again highlighting a theme of surveillance which seems to run throughout the film’s photography. With its almost documentary-like colour photography (which makes strong use of voyeuristic telephoto lenses) and its focus on backbiting within yakuza clans, Retaliation sits somewhere between the ‘borderless action’ films of the 1960s and the jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s. The film has a starkly different ‘look’ to Hasebe’s Massacre Gun; Chris Desjardins has said that Retaliation is shot by Hasebe ‘as if eavesdropping on many scenes’ (Desjardins, op cit.: 127). The photography contains some interesting compositions. From the opening sequence depicting Jiro’s release from prison, characters are often framed in long shot via telescopic lenses which flatten perspective, the foreground of the shot cluttered with objects (eg, blades of grass) that are out of focus, making the shots feel almost voyeuristic in nature. On top of this, in a number of sequences Hasebe uses zoom lenses, operating the zoom to track in on characters in the distance, again highlighting a theme of surveillance which seems to run throughout the film’s photography.

In Takagawa City, exterior sequences are often slightly over-exposed, as if to emphasise the ideal nature of the lives of the farmers. Close-ups of Saeko, the locus of Jiro’s gang’s connection with the farmers, are shot with diffuse lighting, whilst the yakuza tend to be shot with a much harsher, far less forgiving lighting scheme. There’s an impressive level of detail on display in this HD presentation. Some sequences have a diffuse look which I suspect is owing to the characteristics of the zoom and telephoto lenses used to shoot the film (as compared with the crisp nature of the wide-angle lenses with which Hasebe’s Massacre Gun was shot, for example). Contrast levels are good but not excellent (which seems to be a characteristic of colour Japanese films of this era and is therefore most likely a product of the original photography rather than a fault of this presentation), and a strong encode ensures the film has a natural, organic and film-like look.  NB. Some larger screengrabs can be found at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is a strong, punchy track – showcased in sequences which feature the film’s percussive score. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes: - The film’s trailer (2:44). - An interview with Tony Rayns (31:25). Rayns offers some detailed, well-researched information about Retaliation, situating it within the context of Nikkatsu’s films generally and talking about the work of the film’s director, Hasebe. It’s a superb accompaniment to the interview with Rayns that is to be found on Arrow’s Massacre Gun disc. - An interview with Shishido Jô (13:33). Actor Shishido reflects on his career and, in particular, his work with director Hasebe. - A stills gallery (16 images). The film is housed in a clear plastic case with reversible art options (new artwork on the front, and an example of the film’s original artwork on the reverse). As to be expected from Arrow these days, a handsomely put together and nicely-illustrated booklet contains new writing on the film. The release is a ‘dual format’ release, and includes a DVD with the same contents as the Blu-ray disc.

Overall

In many ways, Retaliation seems like a transitional yakuza film, sitting on the cusp of the changeover from the mokukuseki akushon era and the more nihilistic jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s. Hasebe depicts the new breed of yakuza as backstabbers and manipulators who will renege on a deal and are solely motivated by profit, rather than the old principles of honour and respect. ‘I didn’t realise they were such deceitful bastards’, Jiro says at one point, in reference to the Hazama clan. ‘What did you expect?’, Hino asks him, ‘All yakuza are’. Photographically, the film is very interesting, owing to the use of telephoto lenses and zooms. In all, it’s an entertaining, action-packed yakuza picture, handled masterfully by Hasebe. Arrow’s Blu-ray contains a solid presentation of the film and some very good contextual material. Like Massacre Gun, Retaliation has had little exposure on English-friendly home video, and Arrow’s releases of both films are highly recommended. In many ways, Retaliation seems like a transitional yakuza film, sitting on the cusp of the changeover from the mokukuseki akushon era and the more nihilistic jitsuroku pictures of the 1970s. Hasebe depicts the new breed of yakuza as backstabbers and manipulators who will renege on a deal and are solely motivated by profit, rather than the old principles of honour and respect. ‘I didn’t realise they were such deceitful bastards’, Jiro says at one point, in reference to the Hazama clan. ‘What did you expect?’, Hino asks him, ‘All yakuza are’. Photographically, the film is very interesting, owing to the use of telephoto lenses and zooms. In all, it’s an entertaining, action-packed yakuza picture, handled masterfully by Hasebe. Arrow’s Blu-ray contains a solid presentation of the film and some very good contextual material. Like Massacre Gun, Retaliation has had little exposure on English-friendly home video, and Arrow’s releases of both films are highly recommended.

References: Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris Jacoby, Alexander, 2008: A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day. California: Stonebridge Press Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|