|

|

Caliber 9 AKA Milano calibro 9 AKA The Contract (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th June 2015). |

|

The Film

'You Have to Accept It': Fate and Power in Fernando di Leo's Milano calibro 9 (1972) 'You Have to Accept It': Fate and Power in Fernando di Leo's Milano calibro 9 (1972)

In a world of tough guys and even tougher breaks, there is one overriding principle: fate. You can't escape it. You must play the hand you've been dealt. How effectively you play that hand... well, that depends on your skill. If there's a central theme that informs the work of Fernando di Leo, it's the struggle with fate. In exploring this theme, di Leo's movies tread the fine line between European cinema and American popular cinema. In terms of their aesthetic (and, more obviously, their setting), they are recognisably Italian, but at the same time they concern themselves with themes that obsessed Hollywood Renaissance filmmakers of the late 1960s and 1970s, like Sam Peckinpah and Arthur Penn: the battle of the sexes in an age of women's lib (and the interplay between traditional macho male heroes and their increasingly liberated 'molls'); do we really have control over our own lives; and what battles, if any, are worth fighting? Indeed, it would have been interesting to see how di Leo would have approached a script like The Cincinatti Kid (Norman Jewison, 1965), with its card-game-as-metaphor-for-life message. However, some of di Leo's movies are rebuttals of the messages to be found in the films of his Hollywood contemporaries: for example, Milano calibro 9 (released in America as Caliber 9) is in many ways a rejection of the ideas to be found in a picture such as Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971), and this rebuttal can be found in the dialogues between Frank Wolff and Luigi Pistilli’s characters in Milano calibro 9. This is an aspect of di Leo's work that I will return to later.  Born in 1932, during his youth di Leo achieved a degree of success with his contributions to Italian theatre, poetry and literature, publishing his first collection of poems (Le intenzione, ‘The Intention’) in 1960, and following this up with a collection of twenty inter-related short stories entitled I Racconti della Provincia (‘Stories of the Provinces’). Before becoming involved in filmmaking, he also published a semi-autobiographical novel entitled I Nostri Atti (‘Our Deeds’), and worked on adaptations of classic dramatic texts. Born in 1932, during his youth di Leo achieved a degree of success with his contributions to Italian theatre, poetry and literature, publishing his first collection of poems (Le intenzione, ‘The Intention’) in 1960, and following this up with a collection of twenty inter-related short stories entitled I Racconti della Provincia (‘Stories of the Provinces’). Before becoming involved in filmmaking, he also published a semi-autobiographical novel entitled I Nostri Atti (‘Our Deeds’), and worked on adaptations of classic dramatic texts.

In the 1960s, however, di Leo became involved in the world of cinema. After attending the C.S.C. in Rome (the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Europe’s oldest film school, founded in 1935, and now known as the Scuola Nazionale del Cinema), he directed a segment within the portmanteau social comedy Gli eroi di ieri, oggi, domani (1963, with Enzo dell'Aquila, Sergio Tau and Frans Weisz) and began to make his mark as a screenwriter. In this capacity, di Leo contributed to Sergio Leone's classic westerns all'italiana (or, 'Spaghetti Westerns') Per un pugnio di dollari (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964) and Per qualche dollaro in più (For a Few Dollars More, 1965), as well as Duccio Tessari's Una pistola per Ringo (A Gun For Ringo, 1965) and Il ritorno di Ringo (The Return of Ringo, 1965). Following this, in 1967 di Leo directed his first solo feature length movie, Rose rosso per il Führer (Red Roses for the Führer/Code Name, Red Roses), a war drama about the Belgian resistance. However, it was in the 1970s that di Leo delivered the films for which he is most remembered: in 1969, inspired by the work of Kiev-born author Giorgio Scerbanenco, di Leo wrote and directed I ragazzi del massacro (The Boys Who Kill/Naked Violence), the first feature in which di Leo's singular form of Italian noir became fully apparent. After I ragazzi del massacro, di Leo delivered an unusual film in the form of the thrilling all’italiana picture La bestia uccide a sangue freddo (The Beast Kills in Cold Blood, most commonly known in English as Slaughter Hotel, but also released as Asylum Erotica, 1971). Then, in 1972, once again inspired by Scerbanenco's work, di Leo directed Milano calibro 9 (Calibre 9). The first of di Leo's 'milieu trilogy', Milano calibro 9 was followed by La mala ordina (Black Kingpin/Manhunt/The Italian Connection)—released the same year—and Il boss (The Boss/Murder Inferno), the final part of the trilogy, released in 1973. Di Leo continued to work throughout the 1970s, delivering films that mostly fell within the crime genre, until his final feature Killer contro Killers (Killer Vs Killers/Death Commando), which was released in 1985.  Di Leo’s crime films are often grouped with the poliziesco all’italiana films (Italian-style police pictures, sometimes referred to by the originally derogatory label ‘poliziotteschi’) that were popular with Italian audiences during the 1970s and whose violent themes reflected the social turmoil in Italy during the ‘Anni di piombo’ (‘Years of Lead’). Having some of its roots in film-inchiesta (semidocumentary-style investigation films), such as Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962), the poliziesco all’italiana appeared during in the late-1960s, its popularity gathering steam throughout the 1970s and tapping into the zeitgeist of panics surrounding organised crime and domestic terrorism that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing that took place at the National Agrarian Bank in Milan, 1969; this was an event which marked the beginning of a decade dominated by politically-motivated conflicts between the carabinieri and the so-called ‘Red Brigades’. Films within the poliziesco-all’italiana subgenre very often focused on themes of vigilantism or ‘Dirty Harry’-style cops: for example, La polizia ringrazia (Execution Squad; Steno, 1972), a film which is often labeled as helping to define the thematic focus of subsequent examples of the poliziesco all’italiana, focuses on a group of vigilantes which is executing criminals who can’t be brought to justice within the Italian legal system. Later films often encourage the audience to reflect on and identify with the efforts of solo vigilante cops, in a Dirty Harry mold, who take action where the law cannot: the actor Maurizio Merli (Umberto Lenzi’s Napoli violenta/Violent Naples, 1976; Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta/Violent Rome, 1975) became a key part of the iconography of this group of films. Di Leo’s crime films are often grouped with the poliziesco all’italiana films (Italian-style police pictures, sometimes referred to by the originally derogatory label ‘poliziotteschi’) that were popular with Italian audiences during the 1970s and whose violent themes reflected the social turmoil in Italy during the ‘Anni di piombo’ (‘Years of Lead’). Having some of its roots in film-inchiesta (semidocumentary-style investigation films), such as Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962), the poliziesco all’italiana appeared during in the late-1960s, its popularity gathering steam throughout the 1970s and tapping into the zeitgeist of panics surrounding organised crime and domestic terrorism that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing that took place at the National Agrarian Bank in Milan, 1969; this was an event which marked the beginning of a decade dominated by politically-motivated conflicts between the carabinieri and the so-called ‘Red Brigades’. Films within the poliziesco-all’italiana subgenre very often focused on themes of vigilantism or ‘Dirty Harry’-style cops: for example, La polizia ringrazia (Execution Squad; Steno, 1972), a film which is often labeled as helping to define the thematic focus of subsequent examples of the poliziesco all’italiana, focuses on a group of vigilantes which is executing criminals who can’t be brought to justice within the Italian legal system. Later films often encourage the audience to reflect on and identify with the efforts of solo vigilante cops, in a Dirty Harry mold, who take action where the law cannot: the actor Maurizio Merli (Umberto Lenzi’s Napoli violenta/Violent Naples, 1976; Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta/Violent Rome, 1975) became a key part of the iconography of this group of films.

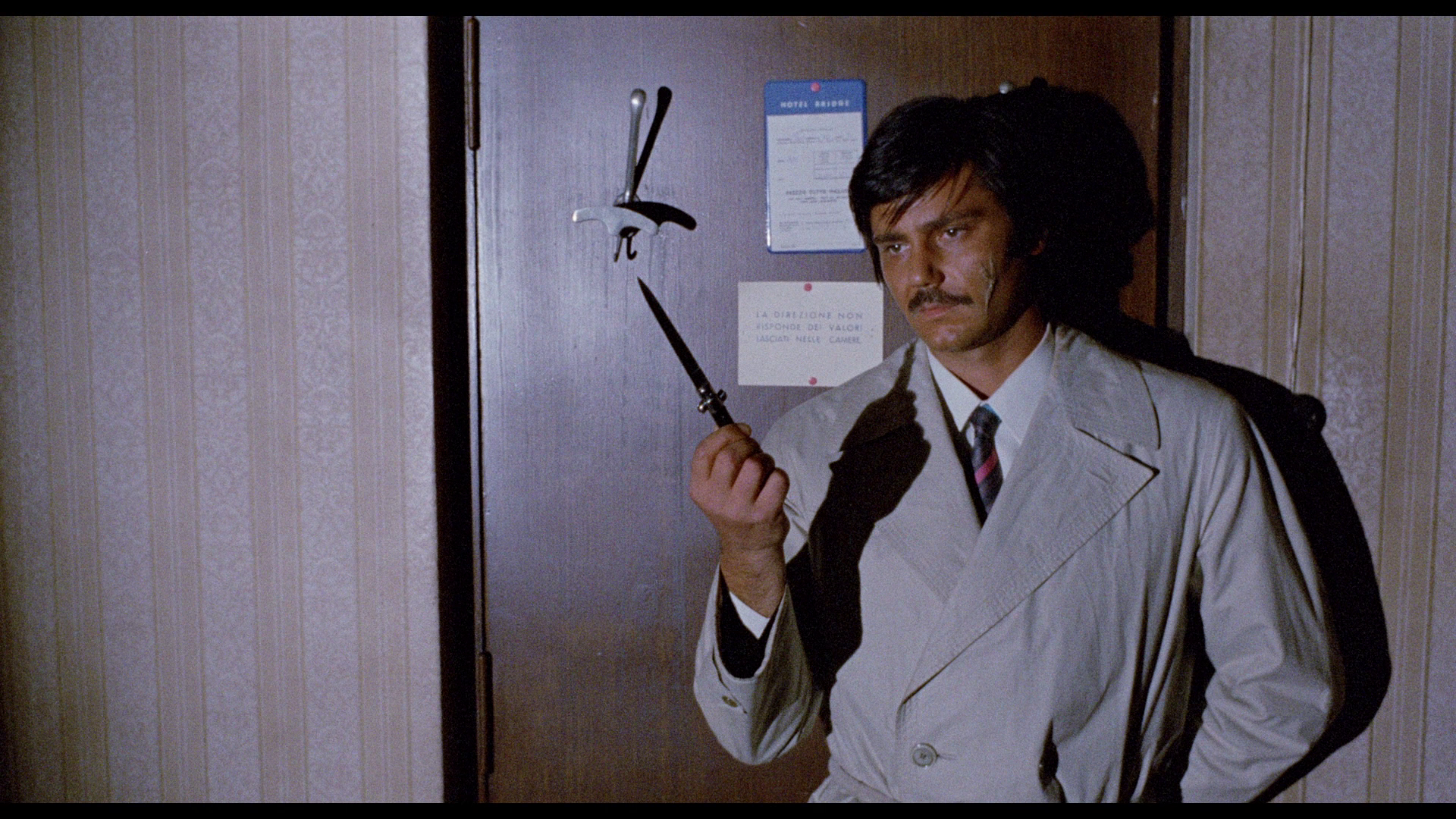

Although there is a specific subset of poliziesco pictures which focus on roving groups of banditti, di Leo’s films—with their focus on underground figures rather than the police themselves—do not fit easily into the paradigms of the poliziesco all’italiana. Rather than the ‘Dirty Harry’ template which many of the poliziesco pictures followed (the ideological underpinnings of which di Leo’s films often subtly, or not so subtly, criticise, as takes place in Milano calibro 9), the films within di Leo’s ‘milieu trilogy’ have more in common with the more socially-conscious American films noirs with an underworld setting rather than a focus on the mechanics of police investigation techniques, such as Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil (1948) or Sam Fuller’s Underworld USA (1961). Since his death in 2003, there has been a resurgence of interest in di Leo's output, and a corresponding growth of critical interest in his films, which appear to be assuming the status of classics within their respective genres. A significant number of his films have been released on home video formats, and in addition, in May 2005 a number of his films were screened at the ICA in London. There have also been rumours of a Quentin Tarantino-helmed rethinking of La mala ordina. However, for admirers of di Leo's work, the core of his career as a filmmaker is the 'milieu trilogy', consisting of Milano calibro 9, La mala ordina and Il boss.  Like I ragazzi del massacro, Milano calibro 9 originated with Giorgio Scerbanenco’s stories. The film’s narrative amalgamates three stories by Scerbanenco, originally published in the anthology Milano calibro 9 in 1969. The film focuses on Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin), an ex-con who, upon being released from prison, finds himself under pressure from both the police (who are convinced that he'll reoffend) and his former criminal confederates: Piazza's former associates believe that Piazza stole a significant amount of money ($300,000) from The Americano (Lionel Stander), a high ranking figure within the criminal underworld of Milan. Throughout the film, Piazza is placed in a position in which—although he appears to wish to 'go straight'—he has little choice but to become involved once again with the criminal fraternity with which he operated before going to jail. Like I ragazzi del massacro, Milano calibro 9 originated with Giorgio Scerbanenco’s stories. The film’s narrative amalgamates three stories by Scerbanenco, originally published in the anthology Milano calibro 9 in 1969. The film focuses on Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin), an ex-con who, upon being released from prison, finds himself under pressure from both the police (who are convinced that he'll reoffend) and his former criminal confederates: Piazza's former associates believe that Piazza stole a significant amount of money ($300,000) from The Americano (Lionel Stander), a high ranking figure within the criminal underworld of Milan. Throughout the film, Piazza is placed in a position in which—although he appears to wish to 'go straight'—he has little choice but to become involved once again with the criminal fraternity with which he operated before going to jail.

In the course of trying to convince The Americano and his gang—including The Americano's 'muscles', Rocco Musco (Mario Adorf) and Pasquale (Mario Novelli)—that he did not steal the money, Piazza also becomes involved with his former moll, Nelly Bordon (Barbara Bouchet). Bordon appears to try to persuade Piazza to leave his criminal past behind. Meanwhile, Piazza enlists the help of his friend Chino (Philippe Leroy), an ally from the time Piazza spent in the service of old-school Mafia ‘godfather’ Don Vincenzo (Ivo Garrani), in his struggle against The Americano's thugs. But once again, things go wrong in The Americano's camp: during a trade-off at which Piazza is present, one of the bagmen is killed and The Americano's money is stolen. The Americano suspects Piazza, but Piazza suggests that it would be more correct for The Americano to suspect Musco. After a dispute, The Americano suggests that he knows who stole the money and enlists Piazza's help in a hit on the anonymous thief. During the hit, Piazza realises that he is being asked to kill Chino and his Don Vincenzo (Ivo Garrani), who in an earlier sequence criticised the 'new generation' of criminals ('They call it the Mafia, but they’re just gangs now. Gangs fighting each other. The real Mafia doesn't exist anymore'). Don Vincenzo is killed, but Chino survives.  Later, at a party held in The Americano's honour, Chino resurfaces and causes mayhem in retribution for Don Vincenzo’s death, killing The Americano's henchmen. After a period of passivity, Piazza joins in. During the battle, a mortally wounded Chino manages to kill The Americano. The Old Order has symbolically eliminated the new generation of criminals, but at the cost of its own extinction. Piazza leaves the site of the massacre and flees to an abandoned church where di Leo's cruel sense of irony becomes most apparent: although throughout the film, we've been led to see Piazza as a victim who cannot escape his life of crime, it is revealed that Piazza did in fact steal The Americano's money and has been concealing this fact from everybody, including his closest friends and allies. Returning with the money to Milan, Piazza encounters Rocco. Rocco discovers that Piazza has stolen the money and the two men develop a new-found respect for each other. Later, at a party held in The Americano's honour, Chino resurfaces and causes mayhem in retribution for Don Vincenzo’s death, killing The Americano's henchmen. After a period of passivity, Piazza joins in. During the battle, a mortally wounded Chino manages to kill The Americano. The Old Order has symbolically eliminated the new generation of criminals, but at the cost of its own extinction. Piazza leaves the site of the massacre and flees to an abandoned church where di Leo's cruel sense of irony becomes most apparent: although throughout the film, we've been led to see Piazza as a victim who cannot escape his life of crime, it is revealed that Piazza did in fact steal The Americano's money and has been concealing this fact from everybody, including his closest friends and allies. Returning with the money to Milan, Piazza encounters Rocco. Rocco discovers that Piazza has stolen the money and the two men develop a new-found respect for each other.

At Nelly's flat, Piazza discovers that he has been betrayed: with her young lover Luca (Salvatore Arico), Nelly conspired to steal The Americano's money, and now they have conspired to kill Piazza and steal his money too. Luca mortally wounds Piazza, who in a fit of rage kills Nelly. At this point, Rocco storms into the room and kills Luca, in respect of the man who was once his enemy, Piazza. One of the central themes of the picture is the issue of 'biding your time': in prison, Piazza has had to bide his time, waiting for his release. And on the outside, he finds that he has to wait in order to find the right time to claim the money he stole from The Americano. Life on the outside is little different from life in prison: when Frank Wolff asks Piazza what he plans to do now he has been released from jail, Piazza replies '[T]ake it easy'; Wolff responds with, 'Just like in jail'. Like life in prison, for Piazza life on the outside is characterised by 'taking it easy': doing your time quietly, with the minimum of trouble. Even Don Vincenzo and Chino are depicted as living an impoverished, prison-like existence in a barely-furnished flat, Vincenzo having fallen from favour (‘We’re not who we were ten years ago’, Ugo notes when meeting with Chino for the first time since his release from prison). The ‘old school’ mob figurehead Vincenzo has been replaced by a new breed of underworld ‘boss’ that is represented by The Americano—who presides over his underworld kingdom from a huge, vulgarly-decorated office within an uncompromising Brutalist-style building. (‘There’s no point in joining Don Vincenzo’, The Americano tells Ugo, ‘He’s a nobody now. He’s a beggar now. His days are numbered’.) The Americano has made his reputation through cruelty and has, as Chino puts it, the deadly combination of ‘influential friends up high and ruthless friends down low’.  Milano calibro 9 is to a large extent about ‘taking it easy’ and the experience of the passivity of waiting. This theme is reinforced in a number of key scenes in which Piazza's stone-faced passivity is put to the test. In one of these scenes, Piazza is by turns interrogated, provoked and threatened by Frank Wolff's police commissioner, who believes that Piazza will naturally return to his criminal roots; in the second scene which revolves around Piazza's passivity, the hotel room in which Piazza is staying is trashed by Rocco and his goons. Piazza remains on the bed, his passive demeanour only dropping when Rocco taunts him about his 'plan to fuck over The Americano'. (Ironically, at this point Rocco is unaware that Piazza has such a plan.) Later, when Piazza visits his friends Don Vincenzo and Chino and Chino loans Piazza some money to pay for the damage to the hotel room, thus getting him off the hook with the police, Rocco and Pasquale burst into the room and harass Chino. Again, Piazza watches on impassively; in close-up, the camera focuses on Piazza’s piercing blue eyes as he gazes at what is taking place off-screen and then averts his eyes, looking downwards to the floor, before returning his gaze to the argument that is taking place between Chino and Rocco. This ‘frozen awareness’, possibly an index of an institutionalised personality and a product of Piazza’s time in prison, returns in the climax, as Chino invades The Americano’s party and, with a handgun, demolishes The Americano’s gang. Piazza again waits on the sidelines, watching silently but intently, before seizing his chance to join in and execute Pasquale within a drained swimming pool. Milano calibro 9 is to a large extent about ‘taking it easy’ and the experience of the passivity of waiting. This theme is reinforced in a number of key scenes in which Piazza's stone-faced passivity is put to the test. In one of these scenes, Piazza is by turns interrogated, provoked and threatened by Frank Wolff's police commissioner, who believes that Piazza will naturally return to his criminal roots; in the second scene which revolves around Piazza's passivity, the hotel room in which Piazza is staying is trashed by Rocco and his goons. Piazza remains on the bed, his passive demeanour only dropping when Rocco taunts him about his 'plan to fuck over The Americano'. (Ironically, at this point Rocco is unaware that Piazza has such a plan.) Later, when Piazza visits his friends Don Vincenzo and Chino and Chino loans Piazza some money to pay for the damage to the hotel room, thus getting him off the hook with the police, Rocco and Pasquale burst into the room and harass Chino. Again, Piazza watches on impassively; in close-up, the camera focuses on Piazza’s piercing blue eyes as he gazes at what is taking place off-screen and then averts his eyes, looking downwards to the floor, before returning his gaze to the argument that is taking place between Chino and Rocco. This ‘frozen awareness’, possibly an index of an institutionalised personality and a product of Piazza’s time in prison, returns in the climax, as Chino invades The Americano’s party and, with a handgun, demolishes The Americano’s gang. Piazza again waits on the sidelines, watching silently but intently, before seizing his chance to join in and execute Pasquale within a drained swimming pool.

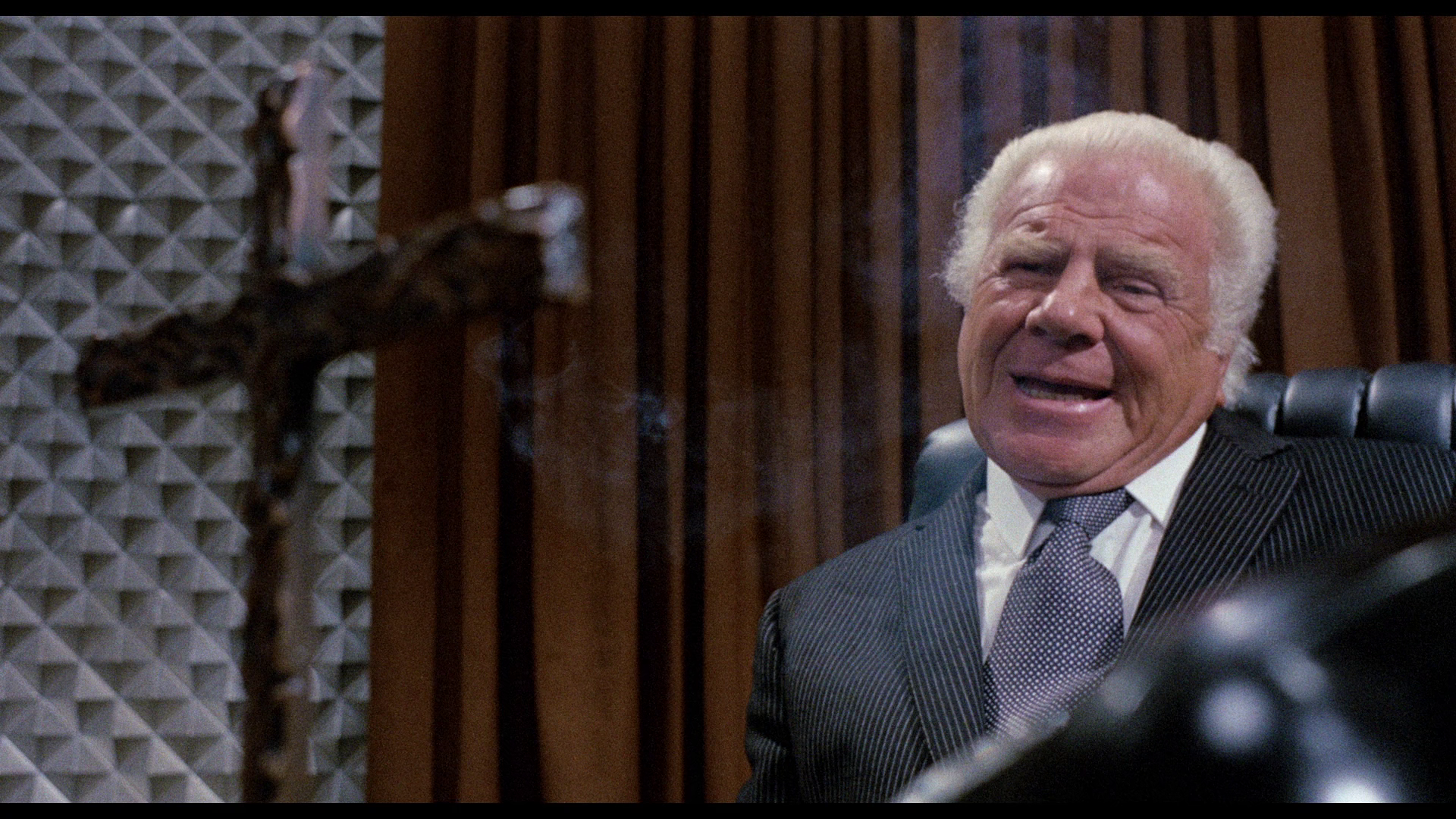

This sense of passivity also ties in with the sense of fatalism that informs the film: like many of di Leo's movies, there is a sense that the characters are doomed from the outset, and that events are only building towards their logical conclusion. All the characters can do is wait for that conclusion to arrive. A recurring theme in di Leo’s work is the idea that our futures are written for us by the powerful: by crooks like The Americano, and by cynical cops like Frank Wolff's character, the unnamed police commissioner.  Throughout much of the film, The Americano is an unseen presence, and in a number of scenes he is likened to a 'God' ('I bet you wish The Americano died while you were in jail', Rocco says to Piazza; 'but he's immortal’. Later, Rocco offers a moment of sententia that links The American’s rhetoric with that of the word of God: ‘You know what The Americano always says: “do unto others what they would do to you… before they do it”'). Religious iconography fills the mise-en-scène: di Leo’s writing credit is presented over an extreme low-angle shot of a church, looking up to it as if to reinforce its authority; in The Americano’s office, as The Americano talks he is shown in close-up, the composition framing his face alongside a crucifix on his desk; one of the few personal effects apparently present within Chino’s bedsit is a picture of the Madonna above his bed; and finally, it is revealed that Piazza has hidden The Americano’s money within a derelict church, and as Piazza wanders through the decaying building to retrieve the bag containing the cash, he is framed alongside a fallen crucifix. When Rocco picks up Piazza after his release from prison, Rocco taunts Piazza from within his car: ‘You, thief! Come sit at the right hand of God Almight’. (The moment when, in the Italian version of the film, this line is spoken is in the English dub silent: this is just one instance in which the English dub, whilst retaining the voices of some of the film’s American actors, loses some of the subtleties of the Italian dialogue.) In effect, The Americano is a 'godhead': something like the Wizard of Oz, he is a figure of respect hidden behind the scenes, a puppeteer who doesn't reveal his presence until it is absolutely necessary. He's the man who pulls the strings of most of the characters in the movie; but as the story of Don Vincenzo's fall from power suggests, The Americano's decline is inevitable. Don Vincenzo’s past reminds us that even the powerful are not immune to the forces of fate. Throughout much of the film, The Americano is an unseen presence, and in a number of scenes he is likened to a 'God' ('I bet you wish The Americano died while you were in jail', Rocco says to Piazza; 'but he's immortal’. Later, Rocco offers a moment of sententia that links The American’s rhetoric with that of the word of God: ‘You know what The Americano always says: “do unto others what they would do to you… before they do it”'). Religious iconography fills the mise-en-scène: di Leo’s writing credit is presented over an extreme low-angle shot of a church, looking up to it as if to reinforce its authority; in The Americano’s office, as The Americano talks he is shown in close-up, the composition framing his face alongside a crucifix on his desk; one of the few personal effects apparently present within Chino’s bedsit is a picture of the Madonna above his bed; and finally, it is revealed that Piazza has hidden The Americano’s money within a derelict church, and as Piazza wanders through the decaying building to retrieve the bag containing the cash, he is framed alongside a fallen crucifix. When Rocco picks up Piazza after his release from prison, Rocco taunts Piazza from within his car: ‘You, thief! Come sit at the right hand of God Almight’. (The moment when, in the Italian version of the film, this line is spoken is in the English dub silent: this is just one instance in which the English dub, whilst retaining the voices of some of the film’s American actors, loses some of the subtleties of the Italian dialogue.) In effect, The Americano is a 'godhead': something like the Wizard of Oz, he is a figure of respect hidden behind the scenes, a puppeteer who doesn't reveal his presence until it is absolutely necessary. He's the man who pulls the strings of most of the characters in the movie; but as the story of Don Vincenzo's fall from power suggests, The Americano's decline is inevitable. Don Vincenzo’s past reminds us that even the powerful are not immune to the forces of fate.

In discussing criminals like Piazza and The Americano, Frank Wolff's character's dialogues with Mercuri (Luigi Pistilli) reveal his distrust of a 'soft touch' to criminals and his belief that justice should concern itself with retribution rather than rehabilitation. As such, Frank Wolff's character is an example of hyperbole, an exaggeration of the 'supercops' that, during the 1970s, were becoming popular in US cinema, inspired by the success of Don Siegel's Dirty Harry (1971). Wolff's character's cynicism and narrow-mindedness are revealed in the somewhat didactic scenes in which he discusses (in something approaching Socratic dialogues) his ideas with Mercuri. Mercuri suggests that the police 'should act on a larger scale [...] Let's get the ones who evict people and who beat up students and workers', and Wolff's response is, 'Stop being a subversive [....] You read too much left-wing material'. As played by Luigi Pistilli, Mercuri is level-headed in the face of Frank Wolff's agitation, and it's hard not to see Mercuri as the 'voice' of di Leo, especially when he states that 'The Americano is an effect, not a cause. All criminals are an effect [....] [T]he mass of Southerners who come to live up North do the most menial jobs, that noone else will do. They are badly paid, live in poor housing and have no social benefits. No wonder they turn to crime'. Additionally, in their discussion of student protests (and the suggestion that a bomb detonated in one of the sequences was planted by a man with a 'clean record' who had only been arrested for his part in some unnamed 'student protests'), these dialogues also allude to the growth of the Red Brigades during the ‘Anni di piombo’: radical activist/terrorist groups who, in 1972, were beginning to hit the news, growing out of the student movements and spreading from Milan (where this film is set) to other parts of Italy.  But the grand irony of the movie (and the source of its incoherence/self-contradictory nature) is that Wolff is right in his judgement of Piazza: Piazza was set to return to his criminal roots, and he had stolen The Americano's money. Wolff's denouncement of Piazza mid-way through the film as 'a mooch' and 'a manipulator' is revealed at the end of the film to be accurate: Piazza has been just as guilty of manipulating people as his enemy, The Americano. In his last moments, even Piazza's friend Chino realises that Piazza has manipulated him into killing The Americano: in a moment of revelation, he declares 'You finally got me to kill The American'. Moschin’s features seem to register a subtle moment of shame before he leaves the site of the massacre to collect his money. The irony of the closing scene is that Piazza's apparent passivity has belied his status as a manipulator of people: in reality, he is anything but passive. But the grand irony of the movie (and the source of its incoherence/self-contradictory nature) is that Wolff is right in his judgement of Piazza: Piazza was set to return to his criminal roots, and he had stolen The Americano's money. Wolff's denouncement of Piazza mid-way through the film as 'a mooch' and 'a manipulator' is revealed at the end of the film to be accurate: Piazza has been just as guilty of manipulating people as his enemy, The Americano. In his last moments, even Piazza's friend Chino realises that Piazza has manipulated him into killing The Americano: in a moment of revelation, he declares 'You finally got me to kill The American'. Moschin’s features seem to register a subtle moment of shame before he leaves the site of the massacre to collect his money. The irony of the closing scene is that Piazza's apparent passivity has belied his status as a manipulator of people: in reality, he is anything but passive.

And what of the advice given to a man beaten by Piazza for hitting on Nelly? 'You have to accept it': you have to accept it because 'it' is all there is, and there isn’t an awful lot you can do to change ‘it’. This is perhaps the overriding theme of the movie, the ‘message’ that most of the audience are left with: bide your time, but be aware that fate and the powerful will conspire against you until all you can do is ‘accept it’. The film is uncut, with a running time of 101:43 mins. (In the interests of full disclosure, the main body of this review, focusing on the film itself, is an adaptation of an article I wrote about di Leo in 2005.)

Video

Arrow’s presentation of Milano calibro 9 takes up approximately 30Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1, which would seem to be its intended aspect ratio.  The film’s photography tends to use shorter focal lengths (50mm and below, seemingly), with most shots featuring a strong depth of field and staging in depth. (Though, having said that, there are a few shots which seem to feature the use of telephoto lenses to suggest surveillance: for example, as Ugo leaves the prison in the opening sequence and is followed, unknowingly, by Rocco and his gang.) The palette in many scenes is autumnal, dominated by browns and drab greens, suggestive of decay and decline; this is juxtaposed with the harsh, graphic décor of The Americano’s office and Nelly’s flat (where the tension between black and white surfaces dominates). The film’s photography tends to use shorter focal lengths (50mm and below, seemingly), with most shots featuring a strong depth of field and staging in depth. (Though, having said that, there are a few shots which seem to feature the use of telephoto lenses to suggest surveillance: for example, as Ugo leaves the prison in the opening sequence and is followed, unknowingly, by Rocco and his gang.) The palette in many scenes is autumnal, dominated by browns and drab greens, suggestive of decay and decline; this is juxtaposed with the harsh, graphic décor of The Americano’s office and Nelly’s flat (where the tension between black and white surfaces dominates).

Arrow’s presentation is a restoration based on a new 2k scan of the film’s negative. As such, it is noticeably different from the Blu-ray presentation of the film released in America by Raro Video. (Some large screengrabs comparing Arrow’s new release with Raro’s older Blu-ray are included at the bottom of this review.) Arrow’s release contains a sliver of extra information on all four sides of the frame, and the contrast levels are slightly more bold. Additionally, a much stronger encode on the Arrow release (the Raro Video presentation came in at a stingier file size of 14Gb) results in a presentation which is much more organic and film-like, especially in motion, retaining the grain structure of 35mm film and featuring a resultant ‘boost’ in detail because of it. Although this is more noticeable in motion, it is also evident from the still frames presented below. The image within this presentation is detailed, and colour consistency is striking (for example, the bold crimson walls of the nightclub in which Nelly dances; the deep blue nighttime sky against which Chino is offset when he makes the arrangements for Don Vincenzo’s funeral). All of this, and the film’s grain structure, is handled impeccably by the encode. It’s a superb presentation of the film, easily the best home video presentation of this picture to date.

Audio

The viewer is provided with the option of watching the film in Italian with optional English subtitles, or via the English dub (which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing). Although the English dub contains the real voices of some of the English-speaking actors, it’s a much more clunky, less subtle track. The Italian track contains a much more nuanced use of dialogue, with some lines going untranslated in the English dub (eg, Rocco’s declaration to Ugo that he should ‘sit at the right hand of God Almighty’, as noted above). Both tracks are clean and clear, though there’s some slight fluctuation in the Italian track towards the end of the film (as Piazza assembles his gun in Nelly’s flat). On the whole, the Italian track is slightly cleaner, with a stronger sense of range; this is evident from the opening sequence’s use of Luis Bacalov’s score (percussive piano offset by shrill violins) that is punctuated with ‘prog rock’ stylings by the Naples-based group Osanna.

Extras

The disc contains a strong range of contextual material, including a number of featurettes produced for the film’s release on DVD by Raro Italia in 2004, alongside a new featurette that features the comedian, actor and writer Matthew Holness reflecting on the position of Milano calibro 9 within the poliziesco all’italiana. The disc contains a strong range of contextual material, including a number of featurettes produced for the film’s release on DVD by Raro Italia in 2004, alongside a new featurette that features the comedian, actor and writer Matthew Holness reflecting on the position of Milano calibro 9 within the poliziesco all’italiana.

'The Making of Milano Calibro 9' (29:42) reflects on the genesis and production of the film. This was included in the Italian DVD release from Raro Video in 2004 and features contributions from di Leo, Philippe Leroy, Barbara Bouchet, Luis Bacalov, the film’s editor Amedeo Giomoni, assistant director Franco Lo Cascio and producer Armando Novelli. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. 'Di Leo: The Genesis of the Genre' (39:13). Again, this was produced for Raro Video’s DVD release and is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. Here, di Leo’s career is explored in some detail, illustrated with clips from his films, and featuring a number of people with whom di Leo worked (including Bouchet, Luc Merenda and Gianni Garko, among many others). It’s an excellent introduction to di Leo’s work and the case for his status as an auteur. 'Scerbanenco Noir' (26:11). This is another featurette sourced from Raro Video’s 2004 DVD release. It focuses on the work of Giorgio Scerbanenco, whose fiction inspired the milieu trilogy. 'Italia Violenta' (17:37). This new featurette features Matthew Holness, the creator of Garth Marenghi, waxing lyrical on di Leo’s work and the poliziesco all’italiana generally. Holness engages with the argument that, in their focus on the underworld, di Leo’s films ‘are much more “noir” than straight action thrillers’ and therefore don’t fit the defining paradigms of the poliziesco films. Holness also suggests there are similarities between Milano calibro 9 and Mike Hodges’ Get Carter (1971) in terms of the ways in which both films are firmly grounded in very clearly-defined cities (Milan and Newcastle, respectively), suggesting the violence that simmers beneath the surface of the hub-bub within these locations. Holness also argues that ‘one of di Leo’s strength is that he’s able to surprise us with conventions we’re already familiar with’. Audio interview with Gaston Moschin (3:25). In this interview, conducted over the telephone, Moschin reflects on his work on the film. His comments are accompanied by still images. Two trailers complete the package: the US trailer (3:15) and the Italian trailer (3:16). The packaging contains reversible artwork, with the film’s original poster design on the reverse, and included within the case is one of Arrow’s characteristically lavishly-produced booklets, containing new writing about the film by Roberto Curti.

Overall

Milano calibro 9 is an impressive film, arguably essential viewing. It’s a shining example of di Leo’s hardboiled style: gritty and exciting, but engaged with issues within its cultural context. Arrow’s release has been a long time coming, having apparently been delayed in order to accommodate a new scan and restoration of the film, but the wait has been worth it: the presentation of the film itself is a noticeable improvement over the previously-available Blu-ray release from Raro Video in the US. The disc contains a good wealth of contextual material, with the pre-existing (and excellent) featurettes produced by Raro for their 2004 DVD release of the film in Italy accompanied by a new featurette featuring Matthew Holness, whose enthusiasm for di Leo's work shines through. It’s a superb release of a great, long-neglected film. Milano calibro 9 is an impressive film, arguably essential viewing. It’s a shining example of di Leo’s hardboiled style: gritty and exciting, but engaged with issues within its cultural context. Arrow’s release has been a long time coming, having apparently been delayed in order to accommodate a new scan and restoration of the film, but the wait has been worth it: the presentation of the film itself is a noticeable improvement over the previously-available Blu-ray release from Raro Video in the US. The disc contains a good wealth of contextual material, with the pre-existing (and excellent) featurettes produced by Raro for their 2004 DVD release of the film in Italy accompanied by a new featurette featuring Matthew Holness, whose enthusiasm for di Leo's work shines through. It’s a superb release of a great, long-neglected film.

Visual comparison with Raro Video’s Blu-ray release. Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

Raro:

Arrow:

More grabs from the Arrow disc:

|

|||||

|