|

|

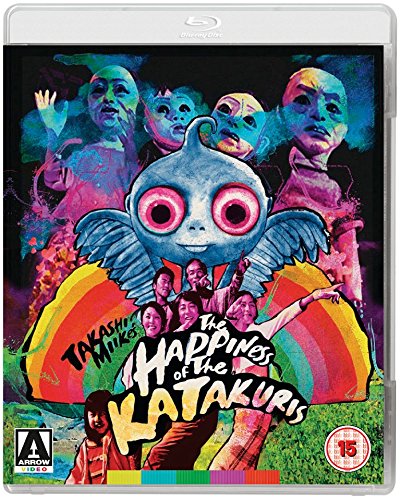

Happiness of the Katakuris (The) AKA Katakuri-ke no kôfuku (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st June 2015). |

|

The Film

The Happiness of the Katakuris (Miike Takashi, 2001) The Happiness of the Katakuris (Miike Takashi, 2001)

Emulating the paradigms of many genres whilst comfortably defying classification, The Happiness of the Katakuris (2001) is in many ways characteristic of its director Miike Takashi’s post-millennial films. Prior to the breakout international success of his nightmarish domestic horror film Audition (1999), which was the first of his films to have a cinema release outside Japan, Miike had been known largely for straight-to-video (‘V-Cinema’) yakuza pictures such as Bodyguard Kiba (1993) and a handful of theatrically-released films which covered similar thematic territory, such as the Black Society Trilogy (Shinjuku Triad Society, 1995; Rainy Dog, 1997; and Ley Lines, 1999). His work since Audition has been a mixture of examples of ‘V-Cinema’ and films intended for cinema release, (though for both Miike tends to favour shooting on high definition digital video), and displays a bewildering sense of diversity. Outside Japan, Miike’s post-Audition films also benefitted from the attention paid towards Japanese cinema by British and American DVD companies during the early-2000s, with Tartan’s Asia Extreme label in particular releasing a significant number of Miike’s films (including The Happiness of the Katakuris) on DVD in the UK and America, helping Miike to find a new and loyal audience. (That momentum has sadly stalled somewhat in recent years, with only a handful of his later films – such as 2012’s Lesson of the Evil – being released in the UK.) His career as a director beginning in 1991, Miike is an extraordinarily prolific filmmaker. (In the year in which he made The Happiness of the Katakuris, Miike directed seven other films.) His time directing examples of ‘V-Cinema’ apparently taught him how to shoot a picture quickly and cheaply, and with a career spanning over eighty pictures he has become a master of making use of whatever resources are available to him whilst also taking advantage of the relatively few restrictions (creatively, owing to the low budgets, and in terms of censorship) that exist within the ‘V-Cinema’ field. The result is a cinema that is often confrontational, unafraid of confronting the taboo, energetic and sometimes abrasive. Miike’s films have acquired an arguably undeserved reputation in the West for violence and sadism, but this is a reductive perspective on the pictures themselves, perhaps owing to the fact that a small handful of his films have, for English-language audiences, arguably overshadowed the remarkable diversity of his body of work as a whole. Whilst there certainly are pictures within his filmography (for example, Ichi the Killer, 2001; or Dead or Alive, 1999) that are outrageously violent, other films (such as Audition) display a sense of restraint that is occasionally punctured by outbursts of excess. Yet more pictures within Miike’s filmography (for example, The Bird People in China, 1998), are much more gentle in their approach. The films themselves encompass work within the crime genre (for example, his 2002 remake of Kinji Fukasaku’s jitsuroku film Graveyard of Honor and his 2003 picture Kikoku/Yakuza Demon), youth pictures (the Crows Zero manga adaptations), period films (Izo, 2004; his remake of Masaki Kobayashi’s Hara-Kiri, 2012), a Spaghetti Western pastiche (Sukiyaki Western Django, 2007), and even children’s films (The Great Yokai War, 2005). However, what links most of the films is a rigorous sense of formalism, an anti-authoritarian stance and a focus on rituals.  Steffen Hantke, discussing Miike’s Audition in detail, highlights the cross-cultural appeal of Miike’s films, suggesting that Audition demonstrated ‘success with a variety of different audiences’ and ‘an ability to cross social and national boundaries: from popular entertainment to arthouse cinema, and from Japan to the West’ (2005: 55). Meanwhile, Miike himself professes little interest in deliberately attempting to court non-Japanese audiences: ‘I have no idea what goes on in the minds of people in the West and I don’t pretend to know what their tastes are. And I don’t want to start deliberately thinking about that. It’s nice that they liked my movie, but I’m not going to start deliberately worrying about why or what I can do to make it happen again’ (Miike, quoted in ibid.). This nonchalance is a part of Miike’s aesthetic, an integral part of the films themselves: Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton note that Miike’s films have a ‘bold style: hard-hitting, flamboyant, nihilist, and above all, “cool”’ (2012: np). However, this nihilism arguably masks more profound concerns within the pictures: Mathijs and Sexton cite Aaron Gerow’s assertion that Miike’s films ‘offer a veil of superficiality that cloaks a visceral politics of diversity’ (ibid.). Steffen Hantke, discussing Miike’s Audition in detail, highlights the cross-cultural appeal of Miike’s films, suggesting that Audition demonstrated ‘success with a variety of different audiences’ and ‘an ability to cross social and national boundaries: from popular entertainment to arthouse cinema, and from Japan to the West’ (2005: 55). Meanwhile, Miike himself professes little interest in deliberately attempting to court non-Japanese audiences: ‘I have no idea what goes on in the minds of people in the West and I don’t pretend to know what their tastes are. And I don’t want to start deliberately thinking about that. It’s nice that they liked my movie, but I’m not going to start deliberately worrying about why or what I can do to make it happen again’ (Miike, quoted in ibid.). This nonchalance is a part of Miike’s aesthetic, an integral part of the films themselves: Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton note that Miike’s films have a ‘bold style: hard-hitting, flamboyant, nihilist, and above all, “cool”’ (2012: np). However, this nihilism arguably masks more profound concerns within the pictures: Mathijs and Sexton cite Aaron Gerow’s assertion that Miike’s films ‘offer a veil of superficiality that cloaks a visceral politics of diversity’ (ibid.).

Despite their outward diversity, there are some key recurring themes within Miike’s work. One of these is the concept of liminality. Gerow highlights the extent to which Miike’s characters are almost always positioned within ‘liminal settings (in-between places such as rooftops, tracks, streets), [and] Miike’s characters also find themselves hovering in between hero and coward. Characters in Dead or Alive claim to be “like Japanese but not Japanese, like Chinese but not Chinese”; Ichi in Ichi the Killer is both super-hero and cry-baby’ (ibid.). In City of Lost Souls (2000), set in Japan, the politics of identity are foregrounded: the protagonist is a Japanese-Brazilian named Mario (Teah), and his girlfriend Kei is Chinese (Michelle Reis). The inn within The Happiness of the Katakuris is a similarly liminal space, something which I will explore later. Another key theme within Miike’s work is an exploration of ‘dove style violence’: ‘a form of violence in which “human beings coldly abuse one another with a detached cruelty reminiscent of ‘certain species of bird’ who, when a flock member is different or weaker… peck at the weakest bird dispassionately until it’s dead”’ (McRoy, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). A number of the films investigate, in its many forms, ‘ijime’ (or bullying) as a form of ‘dove-style violence’: ‘Ichi the Killer shows not just the impact of the bullying, but the fallout as well’ (ibid.). This results in ‘a representation of violence that is both painful and playful, and a reconsideration of the transgressive violence of desire’ (ibid.). The Happiness of the Katakuris is a loose remake of a South Korean black comedy, The Quiet Family (Jee-Woon Kim, 1998), about a family who move from the city to open a mountain inn. When their first guest commits suicide, the family attempt to avoid bad publicity by burying the body. This is only the beginning of the family’s bad luck, as subsequent guests also meet unfortunate demises, leading to the family having to bury even more bodies whilst continually facing the prospect that these bodies will be discovered. The Quiet Family was the directorial debut of Jee-Woon Kim, who has quietly acquired a reputation as a South Korean director-of-note, an auteur of the status of Miike himself, owing to films such as A Tale of Two Sisters (2003), A Bittersweet Life (2005) and I Saw the Devil (2010).  The Happiness of the Katakuris focuses on the Katakuri family who, headed by patriarch Masao (Sawada Kenji), have bought a guesthouse (the White Lovers’ Guesthouse) in the middle of nowhere, with the hope that a new major road being built through the area will result in an upturn in customers. Masao is a former shoe salesman who met his wife Terue (Matsuzaka Keiko) at his job. Masao and Terue are joined by Masao’s father (Tanba Tetsurô); their son Masayuki (Takeda Shinji), a former gangster and ex-con; and daughter Shizue (Nishida Naomi), who has one child, Yurie (Miyazaki Tamaki), from a failed marriage. Yurie’s perspective guides much of the film, and the adult voice of Yurie, speaking from an unspecified point in the future, functions as the film’s narrator, ‘bookending’ the narrative – suggesting perhaps that the excesses within the film may be considered as part and parcel of the child’s comprehension of events. The Happiness of the Katakuris focuses on the Katakuri family who, headed by patriarch Masao (Sawada Kenji), have bought a guesthouse (the White Lovers’ Guesthouse) in the middle of nowhere, with the hope that a new major road being built through the area will result in an upturn in customers. Masao is a former shoe salesman who met his wife Terue (Matsuzaka Keiko) at his job. Masao and Terue are joined by Masao’s father (Tanba Tetsurô); their son Masayuki (Takeda Shinji), a former gangster and ex-con; and daughter Shizue (Nishida Naomi), who has one child, Yurie (Miyazaki Tamaki), from a failed marriage. Yurie’s perspective guides much of the film, and the adult voice of Yurie, speaking from an unspecified point in the future, functions as the film’s narrator, ‘bookending’ the narrative – suggesting perhaps that the excesses within the film may be considered as part and parcel of the child’s comprehension of events.

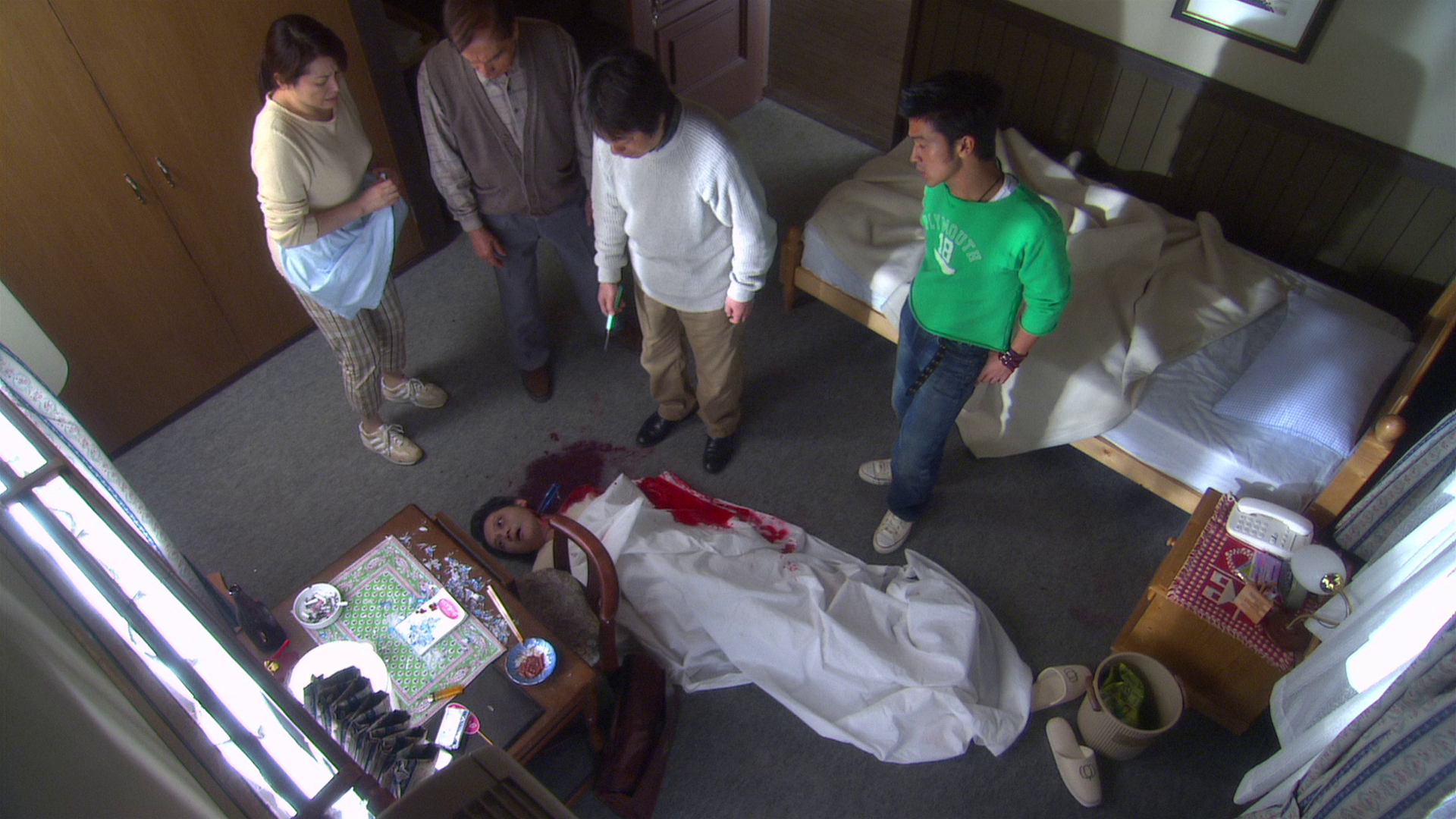

The guesthouse, however, is poorly situated and struggles to attract guests: in fact, as the film opens the guesthouse has had no guests at all. The strangeness of the location, which is near a volcano, is amplified when a passing group of people arrive ‘on a spiritualist training trip’ and evidence mania during an apparently unexpected solar eclipse before moving on. However, for Shizue this encounter, however bizarre, is a positive sign: ‘See, people do come this far’, Shizue notes. During a dark, stormy night, a lone man arrives at the White Lovers’ Guesthouse and books a room. However, whilst alone in his room the man sings a morbid song of farewells (‘And when I get here / It’s a dead end / Darkness creeps up / In whispy shadows’). In the morning, the Katakuris discover that their sole guest is dead, a glass shard through his neck. He has apparently committed suicide but has not left a note. Masao reasons that the revelation that their first guest committed suicide will ruin the business and may lead to members of the family being accused of murder: ‘Say the police let it out that our first guest committed suicide. No-one will ever come and stay here’, he declares. After some disagreement, they decide to dispose of the body, burying the corpse in a shallow grave next to the lake in the nearby forest.  Later, two more guests arrive at the guesthouse: a hugely obese minor celebrity and his very young-looking girlfriend. The couple seem intent on using the guesthouse to allow them to conduct their relationship in private; but during coitus the obese celebrity expires on top of his girlfriend, suffocating her. ‘How come we only get guests like this’, Masayuki asks, ‘What’s the deal with all these dead bodies?’ Once again, the family decided to dispose of the bodies, burying them by the lake alongside the corpse of their first guest. Later, two more guests arrive at the guesthouse: a hugely obese minor celebrity and his very young-looking girlfriend. The couple seem intent on using the guesthouse to allow them to conduct their relationship in private; but during coitus the obese celebrity expires on top of his girlfriend, suffocating her. ‘How come we only get guests like this’, Masayuki asks, ‘What’s the deal with all these dead bodies?’ Once again, the family decided to dispose of the bodies, burying them by the lake alongside the corpse of their first guest.

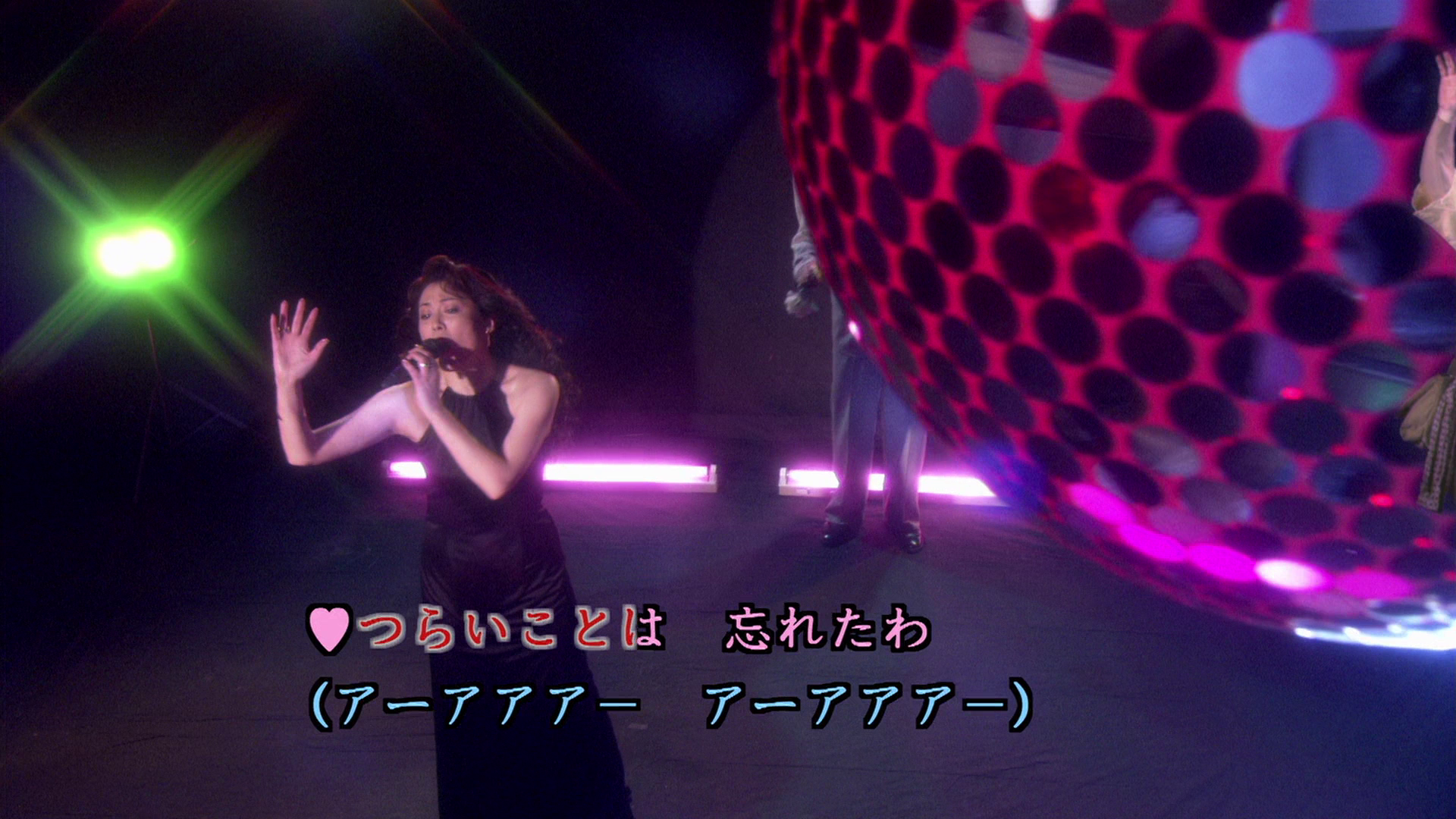

Meanwhile, Shizue meets Richard Sagawa (Imawano Kiyoshirô), who claims to be a British naval captain and a secret agent, and who also declares himself to be related to Queen Elizabeth II. (‘Are you a serviceman’, Shizue asks, referring to Richard’s uniform; ‘I’m with the US Navy’, he replies before correcting himself, ‘No, to be more precise, Britain’s Royal Navy’.) However, unbeknownst to Shizue, Richard is wanted by the police (later developments suggest he is at best a conman, at worst a Bluebeard-type villain). Richard arrives at the guesthouse, his lies becoming more outlandish (‘I remember being cuddled by Aunt Elizabeth’, he says, ‘Diana! If I’d only been there’.) He asks Shizue to lend him some money so that he can return to England, visit ‘Aunt Elizabeth’ and ‘come back rich’. However, Shizue’s grandfather, who is also a spinner of tall tales, recognises Richard for what he is, leading to a fight on top of a nearby landfill and yet another corpse for the family to bury. Masao and Terue are shocked to discover that the major road they have dreamed of will soon be built close to the guesthouse – but will run through the area of land occupied by the lake. The bodies they have buried there will inevitably be discovered. Consequently, the family must disinter the corpses and rebury them elsewhere. However, an escaped murderer arrives at the guesthouse and takes Terue hostage; he is followed closely by a group of policemen. After the situation with the escaped killer has been resolved, the nearby volcano erupts, threatening the guesthouse and the lives of the Katakuris.    Whilst the narratives of The Quiet Family and The Happiness of the Katakuris are very similar, both films approach this basic material in different ways. Steve Rawle has suggested that Miike’s film makes reference to seven key cinematic genres: the family comedy, the disaster movie, the horror film, the murder mystery, claymation, the karaoke video, and the musical (Rawle, 2014: 212). The narrative is punctuated by song-and-dance numbers. The Katakuris burst into song when they discover their first dead guest, and they sing as they bury the corpse. In Shizue’s first meeting with Richard, Miike presents us with an extended song and dance routine (in which both Shizue and Richard participate) with lyrics focusing on the magic of love before revealing that, in reality, Shizue is daydreaming whilst rolling around on the floor, childishly, at Richard’s feet. Here, the staging emulates the elaborate designs of song-and-dance numbers in Hollywood musicals. This sequence finds its ironic echo later in the film, when Richard, after having been revealed to the audience to be a conman, serenades Shizue atop a landfill. (They sit on a bench emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo, which seems like a not-so-subtle dig at American culture.) The staging is similar (with Richard floating into the air during the song’s climax) but the connotations of the environment are radically different. Elsewhere, a song about Masao and Terue’s relationship is presented in the form of a karaoke video (something emphasised by the shot-on-digital video nature of the film itself), with Masao and Terue on a stage and the lyrics presented for the audience at the bottom of the screen – as per the conventions of the karaoke video format. Whilst the narratives of The Quiet Family and The Happiness of the Katakuris are very similar, both films approach this basic material in different ways. Steve Rawle has suggested that Miike’s film makes reference to seven key cinematic genres: the family comedy, the disaster movie, the horror film, the murder mystery, claymation, the karaoke video, and the musical (Rawle, 2014: 212). The narrative is punctuated by song-and-dance numbers. The Katakuris burst into song when they discover their first dead guest, and they sing as they bury the corpse. In Shizue’s first meeting with Richard, Miike presents us with an extended song and dance routine (in which both Shizue and Richard participate) with lyrics focusing on the magic of love before revealing that, in reality, Shizue is daydreaming whilst rolling around on the floor, childishly, at Richard’s feet. Here, the staging emulates the elaborate designs of song-and-dance numbers in Hollywood musicals. This sequence finds its ironic echo later in the film, when Richard, after having been revealed to the audience to be a conman, serenades Shizue atop a landfill. (They sit on a bench emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo, which seems like a not-so-subtle dig at American culture.) The staging is similar (with Richard floating into the air during the song’s climax) but the connotations of the environment are radically different. Elsewhere, a song about Masao and Terue’s relationship is presented in the form of a karaoke video (something emphasised by the shot-on-digital video nature of the film itself), with Masao and Terue on a stage and the lyrics presented for the audience at the bottom of the screen – as per the conventions of the karaoke video format.

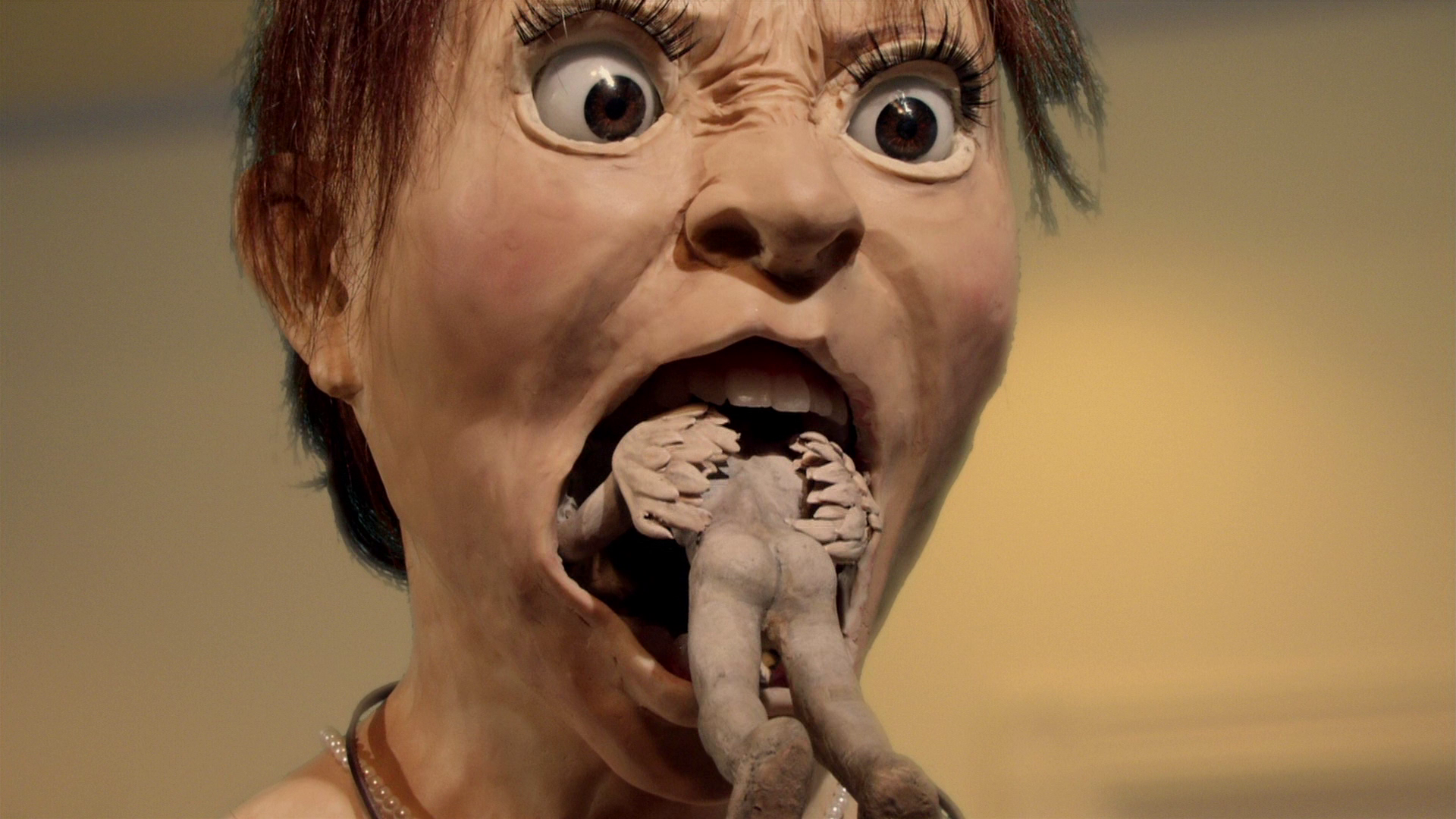

The film’s opening sequence sets its anarchic tone and its eclectic approach to genre conventions. A mixture of live action and stop-motion animation, this sequence depicts a young woman in a restaurant lifting a strange creature out of her soup; as the woman screams, the creature dives into her open mouth and rips out her uvula, making it into the shape of a heart in his hands. (‘My uvula’, the girl cries impossibly.) The uvula floats away like a balloon, and the creature flies out of the window after it. They both land; the creature eats the uvula and is in turn eaten by a crow. Then a teddy bear comes to life and eats the crow. The sequence suggests a circle of consumption and exploitation: the cycle of life rendered absurd by the claymation design of the uvula-loving creature and the combination of live action and stop-motion animation.  The Happiness of the Katakuris was something of a surprise at the time for some of Miike’s Western viewers who were familiar with the director’s work only from Audition and Ichi the Killer, and who knew nothing of Miike’s more ‘gentle’ pictures such as Bird People in China. After Audition’s success, Miike’s work had largely been promoted within Britain and America by being ‘situate[d] […] within a rhetoric of excess and violent, sometimes misogynistic content. The audience had been primed for a Miike whose work was shocking, disgusting, aggressive, agitational and, above all, very violent, often with a sexual overtone’ (Rawle, op cit.: 208). However, The Happiness of the Katakuris ‘does little of this: there is no overt violence, chastened sexuality, no shocking excess, and it’s not extreme’ (ibid.). This is perhaps the reason for the film’s slightly odd reputation as a ‘zombie musical’, given that the ‘zombies’ only appear very briefly in the film (for a single musical number) and during a ‘fantasy’ sequence at that, their presence within this sequence intended to act as a symbol of the family’s escalating sense of panic over the discovery of the corpses they have buried by the lake – whilst the staging provides an obvious parody of John Landis’ video for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’. Rhetoric about the film, seemingly desperate to situate it within the context of Miike’s other films which had found an audience in Britain and America, latched onto this brief sequence within the film and pushed it to the foreground, arguably misrepresenting the picture. The Happiness of the Katakuris was something of a surprise at the time for some of Miike’s Western viewers who were familiar with the director’s work only from Audition and Ichi the Killer, and who knew nothing of Miike’s more ‘gentle’ pictures such as Bird People in China. After Audition’s success, Miike’s work had largely been promoted within Britain and America by being ‘situate[d] […] within a rhetoric of excess and violent, sometimes misogynistic content. The audience had been primed for a Miike whose work was shocking, disgusting, aggressive, agitational and, above all, very violent, often with a sexual overtone’ (Rawle, op cit.: 208). However, The Happiness of the Katakuris ‘does little of this: there is no overt violence, chastened sexuality, no shocking excess, and it’s not extreme’ (ibid.). This is perhaps the reason for the film’s slightly odd reputation as a ‘zombie musical’, given that the ‘zombies’ only appear very briefly in the film (for a single musical number) and during a ‘fantasy’ sequence at that, their presence within this sequence intended to act as a symbol of the family’s escalating sense of panic over the discovery of the corpses they have buried by the lake – whilst the staging provides an obvious parody of John Landis’ video for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’. Rhetoric about the film, seemingly desperate to situate it within the context of Miike’s other films which had found an audience in Britain and America, latched onto this brief sequence within the film and pushed it to the foreground, arguably misrepresenting the picture.

As Steve Rawle has argued, like Visitor Q (which Miike also directed in 2001) The Happiness of the Katakuris alludes to ‘the damaging fallout from the 1990s’ complex recession [the ‘Lost Decade’] that put an end to the economic miracle and bubble economy of the 1980s’ (ibid.: 216). Masao, Rawle suggests, ‘fits the key demographic of many workers laid off between 1993 and 2000’, with many companies aiming to reduce their staff by between 15 and 30 per cent: ‘White-collar workers in particular were subject to this phenomenon, especially senior staff between 45 and 50, where redundancies were prioritised for workers near the top of the salary scales’ (ibid.). Masao ‘represents those senior figures made redundant in the period following 1993’: he is a senior shoe salesman who has fallen prey to the kanri shoku (‘senior staff shock’) (ibid.).   Against this context, and despite their differences, the Katakuris strive to work together as a family unit, to support one another and to achieve happiness and contentment together. As Rawle argues, ‘[r]ather than suggesting a nihilistic and abnegating loss of social cohesion and destruction, the film works to promote happiness, as, despite the challenges the family must overcome, the Katakuris are reunited, deliberately by Masao as a process of recovery’ (ibid.). The isolated guesthouse, seemingly separated from the west of the world, represents one of Miike’s liminal spaces – in which the family must work together and fend off various threats to their stability. Our first glimpse of the family sees Yurie carefully burying a goldfish (foreshadowing the family’s burying of their dead clients later in the narrative), and over this the adult voice of Yurie narrates: ‘Around then I started to wonder what makes a happy family’, she says, ‘We say “family” but we’re all individuals, with our own dreams and problems. It’s said that nature and nurture influence how we grow up. With my family, I know I’ll grow up to be really cool’.  The film narrativises the tension between the needs of the family and the desires of the individual. ‘Guesthouse, bullshit!’, Masayuki declares after the death of the obese celebrity forces the Katakuris to realise that they must once again dispose of their guests’ corpses, ‘This place has no future [….] You [Masao] keep saying “For everyone’s sake”, but your selfishness dragged us up here. Don’t you feel any responsibility?’, Masayuki asks his father. However, though the purchase of the guesthouse was Masao’s idea, it was only in the service of his dream that the family should stay together and work as a unit, supporting one another: ‘Under one roof and sky. My dream of living together’, he narrates, ‘If you want to go, just go; if you feel lonely, then come back’. Masao even has a musical number in which to explain this: during an extended flashback to the purchase of the guesthouse, Masao sings (and is eventually joined in his song by the other members of his family), ‘Let’s live together here / Start together here / On this road to happiness and health’. The deaths of their clients, Richard’s deceit and attempts to manipulate Shizue, the escaped murderer who takes Terue hostage, and finally the volcano, all threaten to destroy the guesthouse – which for the Katakuris represents their family unit and their dream (admittedly imposed by the patriarch, Masao) of achieving happiness together. However, when the volcano strikes, the Katakuris hold hands and, in doing so, form a protective barrier around the house; following this, they find themselves, and the guesthouse, magically relocated to a much more idyllic location where we may assume their business flourishes. Although the guesthouse represents the sense of liminality (or ‘inbetween-ness’) of many of Miike’s other films, The Happiness of the Katakuris shies away from the exploration of ijime (or ‘dove-style-violence’), instead underscoring the importance of working together to overcome such threats to the family unit. The film narrativises the tension between the needs of the family and the desires of the individual. ‘Guesthouse, bullshit!’, Masayuki declares after the death of the obese celebrity forces the Katakuris to realise that they must once again dispose of their guests’ corpses, ‘This place has no future [….] You [Masao] keep saying “For everyone’s sake”, but your selfishness dragged us up here. Don’t you feel any responsibility?’, Masayuki asks his father. However, though the purchase of the guesthouse was Masao’s idea, it was only in the service of his dream that the family should stay together and work as a unit, supporting one another: ‘Under one roof and sky. My dream of living together’, he narrates, ‘If you want to go, just go; if you feel lonely, then come back’. Masao even has a musical number in which to explain this: during an extended flashback to the purchase of the guesthouse, Masao sings (and is eventually joined in his song by the other members of his family), ‘Let’s live together here / Start together here / On this road to happiness and health’. The deaths of their clients, Richard’s deceit and attempts to manipulate Shizue, the escaped murderer who takes Terue hostage, and finally the volcano, all threaten to destroy the guesthouse – which for the Katakuris represents their family unit and their dream (admittedly imposed by the patriarch, Masao) of achieving happiness together. However, when the volcano strikes, the Katakuris hold hands and, in doing so, form a protective barrier around the house; following this, they find themselves, and the guesthouse, magically relocated to a much more idyllic location where we may assume their business flourishes. Although the guesthouse represents the sense of liminality (or ‘inbetween-ness’) of many of Miike’s other films, The Happiness of the Katakuris shies away from the exploration of ijime (or ‘dove-style-violence’), instead underscoring the importance of working together to overcome such threats to the family unit.

The film is uncut and runs for 112:37 mins.

Video

Throughout his 1990s ‘V-Cinema’ films, Miike demonstrated a comfortable approach to shooting his pictures on video. Although he has shot a number of films on 35mm film, many of Miike’s films are shot on video. The Happiness of the Katakuris was shot on HD digital video, and is here presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Throughout his 1990s ‘V-Cinema’ films, Miike demonstrated a comfortable approach to shooting his pictures on video. Although he has shot a number of films on 35mm film, many of Miike’s films are shot on video. The Happiness of the Katakuris was shot on HD digital video, and is here presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

The disc is a clone of the digital master for the film. As such, it’s true to source. As one might expect for a film shot digitally, it has a very crisp and ‘clean’ aesthetic with a clear digital video ‘look’ – which of course, is wholly intentional. In comparison with 35mm film, and as is to be expected from material shot on HD digital video in 2001, contrast is noticeably different to what one would expect from 35mm film, but of course entirely true to the shot-on-DV source material. As digital video (especially from the early 2000s) has noticeably less dynamic range than film, highlights (for example, in a number of scenes, Richard’s very white naval jacket) are often burnt-out and blacks sometimes ‘crushed’ – but once again, this is true to the source material and a characteristic of the shot-on-video nature of the picture. The presentation is a huge improvement upon the DVD releases of the film that have been previously available, with a much stronger level of detail and a greater sense of depth to the photography that is carried by a superb encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track (in Japanese) with optional English subtitles. The track has a pleasing sense of depth to it, swelling when it needs to (for example, with the music that comes with the solar eclipse early in the film), and musical numbers fill the soundscape in a pleasing manner.

Extras

The disc includes two commentaries (one of which is presented in two forms). The first of these is a commentary by Miike Takashi and critic/actor Tokitoshi Shiota, which is presented in Japanese with English subtitles, and in an alternate form via a spoken translation into English. This commentary has appeared on a number of the film’s previous DVD releases, and features Miike discussing the film’s production and some of the ideas contained within the picture. Alongside this, the disc also includes and a new commentary with Tom Mes, the author of Agitator, the excellent volume on Miike’s cinema. Mes’ commentary is excellent and situates The Happiness of the Katakuris within Miike’s body of work as a whole, considering how the film relates to other pictures within Miike’s oeuvre and exploring its themes in detail. Mes also reflects on the film’s institutional context, discussing some of the ways in which the Japanese film industry have changed since the 1990s. Mes talks about his own visit to the film’s set and explores the picture’s relationship with The Quiet Family. The disc includes two commentaries (one of which is presented in two forms). The first of these is a commentary by Miike Takashi and critic/actor Tokitoshi Shiota, which is presented in Japanese with English subtitles, and in an alternate form via a spoken translation into English. This commentary has appeared on a number of the film’s previous DVD releases, and features Miike discussing the film’s production and some of the ideas contained within the picture. Alongside this, the disc also includes and a new commentary with Tom Mes, the author of Agitator, the excellent volume on Miike’s cinema. Mes’ commentary is excellent and situates The Happiness of the Katakuris within Miike’s body of work as a whole, considering how the film relates to other pictures within Miike’s oeuvre and exploring its themes in detail. Mes also reflects on the film’s institutional context, discussing some of the ways in which the Japanese film industry have changed since the 1990s. Mes talks about his own visit to the film’s set and explores the picture’s relationship with The Quiet Family.

The disc also includes a number of interviews, all of which are presented with the interviewees speaking in Japanese with optional English subtitles for the viewer: - a new interview with Miike Takashi (38:59). In this extensive interview recording in 2015, Miike reflects on the film’s production and reception. Miike talks about the relationship between The Happiness of the Katakuris and The Quiet Family and discusses some of the ways in which he attempted to make his own mark on the material. He also reflects on his decision to make a picture that was different to those for which he had become famous in the eyes of non-Japanese audiences, and he talks about the differences between Japanese audiences and those outside Japan. The rest of the interviews are archival interviews and have been seen before: - Miike Takashi (5:03), and cast members Sawada Kenji (5:00), Matsuzaka Keiko (2:48), Imawano Kiyoshiro and Takeda Shinji (4:28), Nishida Naomi (2:19), Tanba Tetsuro (4:04). These interviews were recorded around the time of the film’s production and are essentially promotional pieces. An archival ‘making of’ documentary (30:42), which has also been seen on the film’s previous DVD releases, is included. Again, this is presented in Japanese with optional English subtitles. ‘Animating the Katakuris (5:40), a short featurette, is included. This archival featurette, featuring interviews with Miike and the film’s animation director Kimura Hideki, focuses on the animation techniques used within the film. ‘Dogs, Pimps and Agitators’ (23:51). This superbly written and edited ‘visual essay’ features Tom Mes providing an overview of Miike’s work. Mes’ comments are illuminating for both newcomers and those familiar with Miike’s pictures. Finally, the disc includes the film’s trailer (1:44) and a short TV spot (0:20).

Packaging

Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork. Also included is a lavishly-illustrated booklet, which we have previewed via a PDF version. This booklet contains a new piece of writing about the film by Johnny Mains. Titled 'Katakuris and Corpses', this piece examines The Happiness of the Katakuris within the context of the other films Miike made in 2001, especially Visitor Q, and compares the claymation episodes within the film with the work of Jan Svankmajer. I'd take slight issue with Mains' suggestion that Miike has 'lost his way of late' - that's up for debate and a matter of opinion - but Mains' piece provides a good introduction to the film's context. Also included in the booklet is an archival interview with Miike, conducted by Sean Axmaker. Titled 'I'm Going to Put Something New In It', this interview was conducted in 2002 and explores the origins of Miike's filmmaking career and finds Miike reflecting on the processes involved in the production of his films. Two more pieces round out the booklet: 'The Rock-and-Roll Horror Picture Show' by Stuart Galbraith IV, and 'The Unhappiness of the Quiet Family' by Grady Hendrix. 'The Rock-and-Roll Horror Picture Show' provides discussion of the casting of Sawada and Imawano in the film and discusses the work of these two musicians; 'The Unhappiness of the Quiet Family' focuses on Jee-Woon's The Quiet Family and its relationship with Miike's remake.

Overall

The Happiness of the Katakuris is a delicious black comedy that refuses to be pigeon-holed. At the time of its initial release, its ultimately uplifting message and focus on music and comedy seemed like an intentional challenge to the non-Japanese audience for Miike’s films who had come (incorrectly) to perceive his films as ‘extreme’ and predicated on violence and sadism. Certainly, those elements are present within some of Miike’s films; but Miike’s talents are much more diverse than that. With this film, Miike, ever the agitator, seemed deliberately to refuse to play to the gallery: comparisons may perhaps be drawn with Tom Courtenay’s character in Tony Richardson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) who, once he has proved he can win the race, ‘throws’ it in defiance of authority and allows those behind him to win instead. The Happiness of the Katakuris is a delicious black comedy that refuses to be pigeon-holed. At the time of its initial release, its ultimately uplifting message and focus on music and comedy seemed like an intentional challenge to the non-Japanese audience for Miike’s films who had come (incorrectly) to perceive his films as ‘extreme’ and predicated on violence and sadism. Certainly, those elements are present within some of Miike’s films; but Miike’s talents are much more diverse than that. With this film, Miike, ever the agitator, seemed deliberately to refuse to play to the gallery: comparisons may perhaps be drawn with Tom Courtenay’s character in Tony Richardson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) who, once he has proved he can win the race, ‘throws’ it in defiance of authority and allows those behind him to win instead.

The film’s gallows humour is what shines through the most. Trying to lower the corpse of the obese celebrity out of the window of his room in the guesthouse, the Katakuris struggle at first; they lower the body gently, until Terue reminds them, ‘It’s not like he’s breakable’. This results in the family dropping the corpse abruptly to the ground. Later, when some ‘normal’ guests (a family with two young children) arrive and take a room at the guesthouse, the mother asks the Katakuris if they have a length of cord that she may use. ‘Cord?’, the Katakuris ask in unison, collectively miming the act of tying the cord around their throats. However, the woman only wants to use the cord as an improvised belt for her young son’s trousers. The film explores the theme of liminality that is a characteristic of Miike’s films, and also touches on the issue of ‘dove-style violence’. Like many of Miike’s films (and a large number of other Japanese films) this is framed against the fallout from the ‘Lost Decade’ (the Ushinawareta Jūnen) and the recession that hit Japan in the 1990s. However, The Happiness of the Katakuris represents these issues in a way that reinforces the importance of negating individual desire and working together to overcome the troubles that beset the guesthouse, symbolic of the family’s (Japan’s?) future prosperity. It’s a challenging, hugely entertaining film that rewards viewers who approach it with an open mind. Arrow’s release is exemplary, containing an excellent presentation of the film: it’s worth bearing in mind that The Happiness of the Katakuris was shot on digital video, and therefore has a very ‘digital’ look (a very ‘clean’ image; a lower dynamic range resulting in blown-out highlights; noticeably different contrast levels than 35mm film) that is, of course, entirely true to the source material. In terms of the film’s presentation, given the release’s status as a clone of a digital master, the encode is what matters here, and it’s a superb one. The main presentation is supported by some excellent contextual material. Some of this has been seen before and will be familiar to Miike’s fans, but the new content (the new interview with Miike, Tom Mes’ audio commentary, and the ‘visual essay’ by Mes) is superb and helps provide a strong context for the picture, both for Miike’s fans and for new viewers of the film. In sum, this is an excellent, very pleasing release of The Happiness of the Katakuris, with a superb presentation of the film that is supported with some very impressive contextual material. For Miike’s fans, the decision as to whether or not to upgrade to this new Blu-ray release should be, as they say, a ‘no-brainer’. References: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo, 2009: ‘Introduction’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo, 2009: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 1-12 Hantke, Steffen, 2005: ‘Japanese Horror Under Western Eyes: Social Class and Global Culture in Miike Takashi’s Audition’. In: McRoy, Jay (ed), 2005: Japanese Horror Cinema. Edinburgh University Press: 54-65 Mathijs, Ernest & Sexton, Jamie, 2012: Cult Cinema. London: Wiley-Blackwell Rawle, Steve, 2014: ‘The Ultimate Super-Happy-Zombie-Romance-Murder-Mystery-Family-Comedy-Karaoke-Disaster-Movie-Part-Animated-Remake-All-Singing-All-Dancing-Musical-Spectacular-Extravaganze: Miike Takashi’s The Happiness of the Katakuris as “Cult” Hybrid’. In Hunt, Leon et al (eds), 2014: Screening the Undead: Vampires and Zombies in Film and Television. London: I B Tauris: 208-32 Shin, Chi-Yun, 2009: ‘The Art of Branding: Tartan “Asia Extreme” Films’. In: Choi, Jinhee & Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo, 2009: Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema. Hong Kong University Press: 85-100

|

|||||

|