|

|

Man with the Golden Arm (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th June 2015). |

|

The Film

The Man with the Golden Arm (Otto Preminger, 1955) The Man with the Golden Arm (Otto Preminger, 1955)

Based on Nelson Algren’s 1949 novel of the same title, Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) offers a surprisingly stark depiction of heroin addiction. John Garfield had originally planned to adapt the novel to the screen with the co-operation of screenwriter Lewis Meltzer, Algren and an addict acquaintance of Algren’s named ‘Acker’, who was to function as the picture’s technical adviser. However, after Algren and Acker traveled to Los Angeles, Algren found the meetings with Garfield and Garfield’s producer Bob Roberts to be less than productive, with Garfield apparently evidencing disengagement from the project by interrupting the meetings to schedule games of tennis and Roberts serving Algren with a series of summonses (Simon, 1996: 113). Although an agreement was reached to continue the project, and once he returned to Chicago Algren continued to adapt his novel into a screenplay, the experience embittered Algren towards Hollywood (ibid.). For his part, Garfield was reputedly alienated from the project once he learnt that owing to its focus on drug addiction, it would inevitably cause problems with the Production Code Authority (Hirsch, 2011: np). Unfortunately, the McCarthy hearings led to well-documented trouble for Garfield, who refused to name names and eventually died in 1952 of a heart attack, aged only 39. Eventually, the project found its way into the hands of Otto Preminger, who bought the rights to Algren’s novel from Garfield’s estate and hired Algren to adapt his own novel into screenplay form to the tune of a thousand dollars per week. However, with little to no experience of writing screenplays, Algren struggled with the adaption and was eventually replaced with Robert Alan Aurthur, who was in turn replaced with Walter Newman, whose first feature film screenplay had been for Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951) (ibid.). Preminger directed the film adaptation of Algren’s novel in 1955, and upon the film’s release Algren vocalised his dissatisfaction with the experience and the changes made to his narrative, referring to the film as the product of ‘my war with the United States as represented by Kim Novak’ (Algren, quoted in ibid.: 114). (Algren was similarly dissatisfied with Edward Dmytryk’s 1962 adaptation of his novel Walk on the Wild Side.)  The film focuses on Frankie Majcinek, aka Frankie Machine (Frank Sinatra), who, after being released from prison where he has spent most of his time in a medical facility being treated for heroin addiction, returns to the Chicago streets. After paying a visit to his friends, including the simple-minded Sparrow (Arnold Stang), at the neighbourhood bar, he returns to the small bedsit in which he lives with his wife Sophia (Eleanor Parker), whom Frankie nicknames ‘Zosch’. Frankie feels responsible for Zosch, who he married after his drink driving caused an accident which (he believes) confined her to a wheelchair. However, unbeknownst to Frankie, Zosch is entirely able-bodied: she only pretends not to have the use of her legs in order to keep Frankie beholden to her. The film focuses on Frankie Majcinek, aka Frankie Machine (Frank Sinatra), who, after being released from prison where he has spent most of his time in a medical facility being treated for heroin addiction, returns to the Chicago streets. After paying a visit to his friends, including the simple-minded Sparrow (Arnold Stang), at the neighbourhood bar, he returns to the small bedsit in which he lives with his wife Sophia (Eleanor Parker), whom Frankie nicknames ‘Zosch’. Frankie feels responsible for Zosch, who he married after his drink driving caused an accident which (he believes) confined her to a wheelchair. However, unbeknownst to Frankie, Zosch is entirely able-bodied: she only pretends not to have the use of her legs in order to keep Frankie beholden to her.

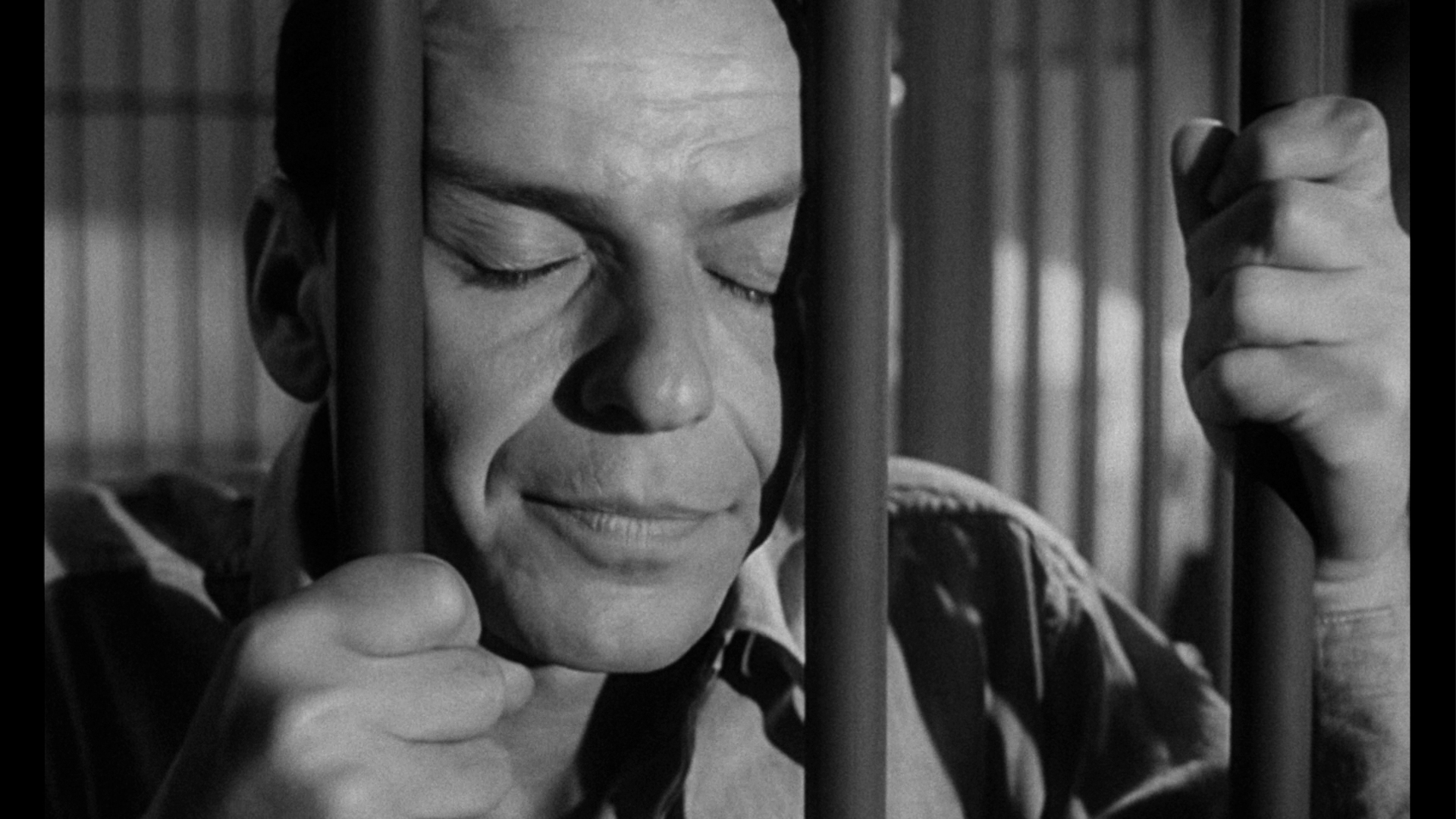

At the hospital, Frankie learnt to play the drums and was considered a natural talent. The doctor treating Frankie, Dr Lennox, gave Frankie the contact details for Harry Lane (Will Wright), with the intention that Frankie should telephone Lane upon his released and arrange an audition to exploit Frankie’s musical talents and help Frankie from returning to the same old lifestyle that facilitated his heroin addiction. However, Zosch has other ideas, pestering Frankie to return to his work as a ‘house’ dealer in illicit card games organised by local hoodlum Schwiefka (Robert Strauss), so that Frankie may pay for Zosch to be treated by a local ‘quack’, a private doctor specialising in alternative medicine, rather than visiting the free clinic for treatment. Frankie’s friendship with Sparrow reaps an unpleasant reward when Sparrow is hauled in by the police for shoplifting and an entirely innocent Frankie is arrested as Sparrow’s accomplice. The police are convinced that Frankie will return to his criminal ways. Whilst in jail, Frankie is approached by Schwiefka, who offers to enable Frankie’s release – if Frankie will deal for him in an upcoming card game. In a tight spot, unable to spend time in jail owing to his upcoming audition as a drummer, Frankie has no choice but to agree. Events conspire to send Frankie back to his former life as Schwiefka’s associate Louie (Darren McGavin), a drug peddler, pecks at Frankie and tries – eventually successfully – to get him to take a fix (‘Why fight it, Dealer? For who? For what?’). The first fix is for free, but after that Louie has his claws in Frankie, who despite his claims to the opposite rapidly becomes hooked once again on junk.  Meanwhile, Frankie reunites with his true love, Molly (Kim Novak), who lives in the rooms downstairs. Whilst out of her own self-interest Zosch nags Frankie to return to his work as a dealer for Schwiefka, Molly persuades Frankie to pursue his ambition of becoming a musician. Frankie manages to secure a big audition with a band but Schwiefka and Louie want Frankie to work his magic at a big card game they are holding. Frankie agrees and makes a big win for the house. Frankie retires from the game, but is jonesing for a fix: Louie offers to give it to Frankie if he continues to deal in the game. Frankie has no choice but to agree; the days turn into nights and back again. It’s almost a dead cert that Frankie will miss his big audition. Exhausted, Frankie loses a number of hands, and Schwiefka persuades him to cheat; Frankie is caught out and beaten by some of the other participants in the card game, whilst Shwiefka distances himself from his ‘golden’ dealer. Louie denies Frankie a fix, and Frankie arrives for his audition strung out, bruised and exhausted. Naturally, the audition isn’t a success, and Frankie walks out before it has ended. Meanwhile, Frankie reunites with his true love, Molly (Kim Novak), who lives in the rooms downstairs. Whilst out of her own self-interest Zosch nags Frankie to return to his work as a dealer for Schwiefka, Molly persuades Frankie to pursue his ambition of becoming a musician. Frankie manages to secure a big audition with a band but Schwiefka and Louie want Frankie to work his magic at a big card game they are holding. Frankie agrees and makes a big win for the house. Frankie retires from the game, but is jonesing for a fix: Louie offers to give it to Frankie if he continues to deal in the game. Frankie has no choice but to agree; the days turn into nights and back again. It’s almost a dead cert that Frankie will miss his big audition. Exhausted, Frankie loses a number of hands, and Schwiefka persuades him to cheat; Frankie is caught out and beaten by some of the other participants in the card game, whilst Shwiefka distances himself from his ‘golden’ dealer. Louie denies Frankie a fix, and Frankie arrives for his audition strung out, bruised and exhausted. Naturally, the audition isn’t a success, and Frankie walks out before it has ended.

Meanwhile, Louie pays a visit to Zosch and, walking in unannounced, discovers that her disabled act is a sham. Frustrated by the knowledge that Louie will surely tell Frankie that Zosch has been stringing him along and playing on his sense of responsibility for her, Zosch pushes Louie down the stairwell. The fall kills Louie, and the police are convinced that Frankie killed the dope peddler. Frankie goes on the lam, hiding out in Molly’s rooms and going ‘cold turkey’, before attempting to clear his name. Upon his release from prison (or rather, the prison hospital in which he’s been treated for his narcotics addiction), Frankie is buoyed by positivity about his new-found talent for playing the drums and his ability to kick the habit of a lifetime. Returning to Chicago, he visits the neighbourhood bar and sees Louie – his flashy clothing in stark contrast to the dress of the other patrons – cruelly taunting a one-armed, one-legged drunk, making him dance for a shot of whiskey (‘Nothin’ like that first drink of the day’, Louie teases the man). Louie offers Frankie a hit, but Frankie turns him down. Frankie’s other acquaintances ask Frankie how he’s been. ‘Greatest place you’ve ever seen’, Frankie tells them joyously, ‘Ball games, great food. I even learned to play the drums’. Frankie’s talent for drumming is, it seems, prodigious: the man who taught him the drums ‘says I’m a natural. “Arms of pure gold”’. Frankie’s ‘arms of pure gold’ (the ‘golden arm’ of the film’s title) also alludes to Frankie’s ability as a card dealer, and the ease with which, in that role, he wins for the house. (‘Take care of that arm’, Schwiefka tells Frankie, stroking his left bicep, before the big card game.)  However, Frankie’s bubble is quickly burst by his wife Zosch, whose cynical manipulation of Frankie (her pretence at being disabled, her attempts at turning him back to working for Schwiefka) marks her as the film’s chief villain. Frankie tells Zosch, ‘I finished with Schwiefka. I don’t deal for him no more’. An anxious Zosch protests sharply, ‘But you always deal. You’re a dealer. You’re the best dealer in the business’. ‘No more. I’m a drummer now’, Frankie tells her matter-of-factly, before practising with his kit. Zosch is displeased with Frankie’s new ambition to become a musician (‘Forget this big job’, she insists), even going to the extent of apparently hiding Frankie’s drumsticks. She wants Frankie to deal for Schwiefka at his card games, as this represents an easy source of money with which she can pay the quack who comes to treat her with alternative therapies. Later, she asks Frankie desperately, ‘Why you gotta go around changing things? Why can’t it be like always?’ Frankie, meanwhile, demonstrates a dog-like devotion for Zosch, for whose apparent disabilities he feels responsible: ‘You can’t make a fool of someone who loves you, and they’re so helpless’, he tells Molly. However, Frankie’s bubble is quickly burst by his wife Zosch, whose cynical manipulation of Frankie (her pretence at being disabled, her attempts at turning him back to working for Schwiefka) marks her as the film’s chief villain. Frankie tells Zosch, ‘I finished with Schwiefka. I don’t deal for him no more’. An anxious Zosch protests sharply, ‘But you always deal. You’re a dealer. You’re the best dealer in the business’. ‘No more. I’m a drummer now’, Frankie tells her matter-of-factly, before practising with his kit. Zosch is displeased with Frankie’s new ambition to become a musician (‘Forget this big job’, she insists), even going to the extent of apparently hiding Frankie’s drumsticks. She wants Frankie to deal for Schwiefka at his card games, as this represents an easy source of money with which she can pay the quack who comes to treat her with alternative therapies. Later, she asks Frankie desperately, ‘Why you gotta go around changing things? Why can’t it be like always?’ Frankie, meanwhile, demonstrates a dog-like devotion for Zosch, for whose apparent disabilities he feels responsible: ‘You can’t make a fool of someone who loves you, and they’re so helpless’, he tells Molly.

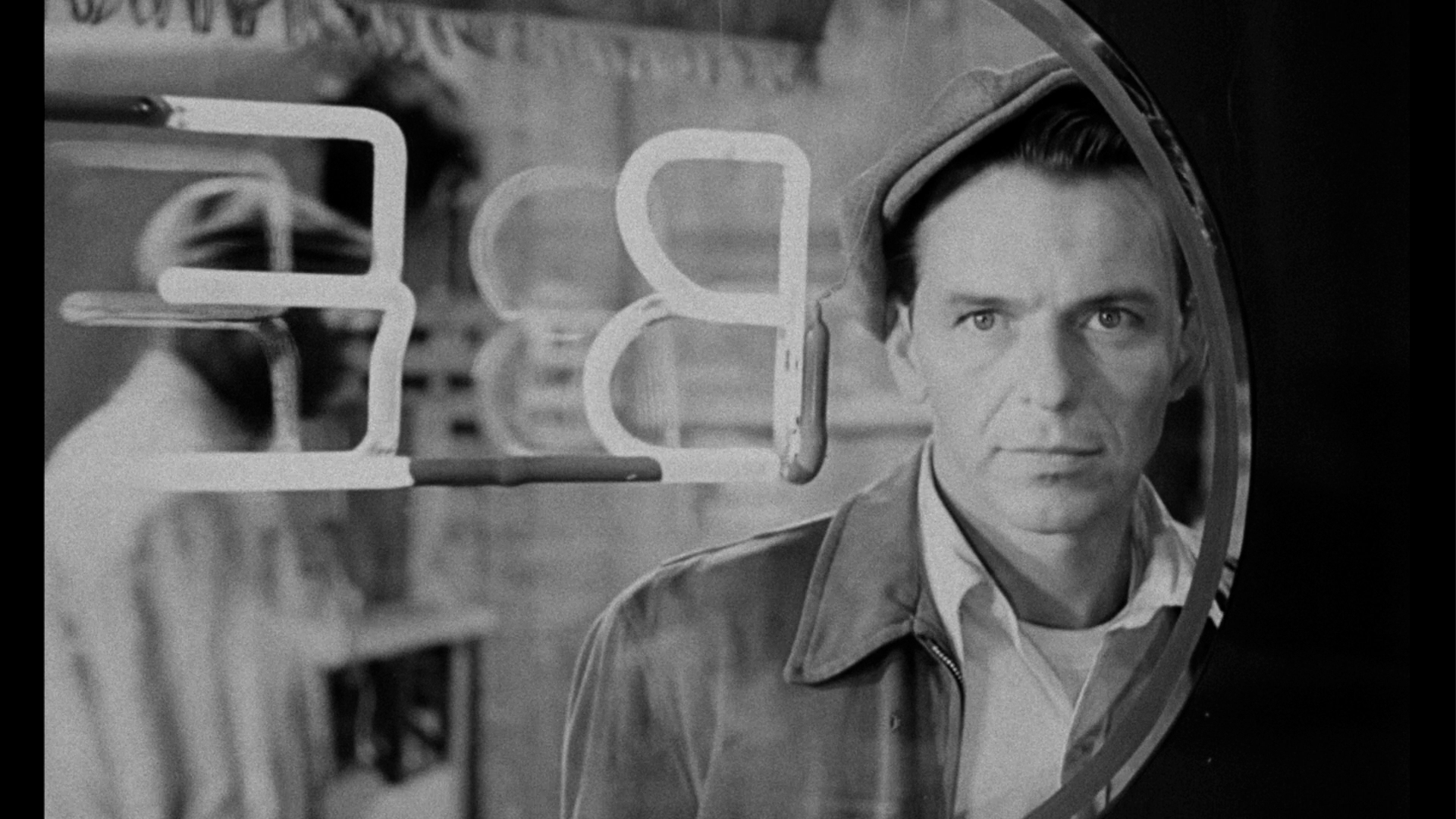

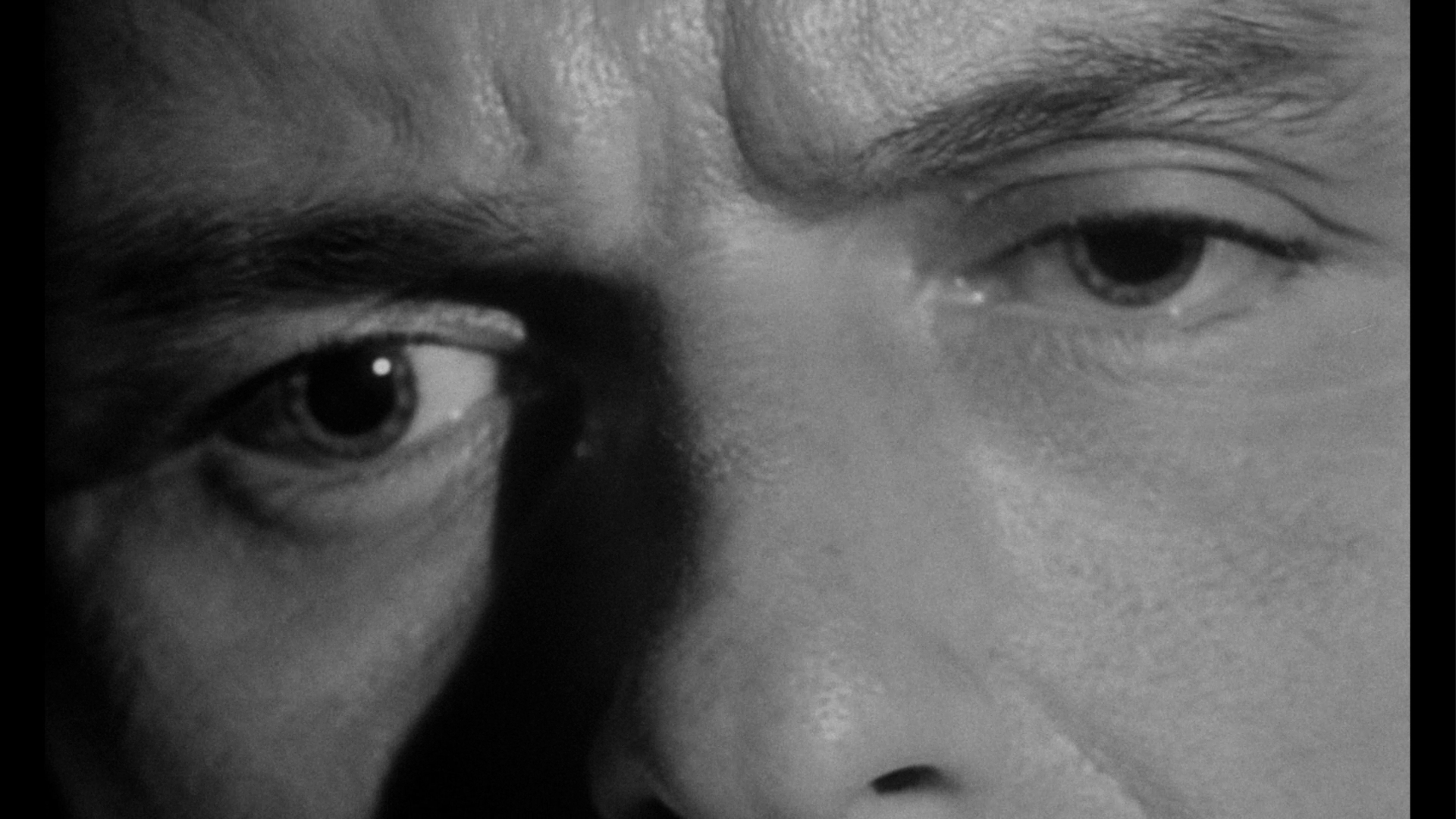

For his part, Schwiefka pecks at Frankie to work as his dealer once again, aided by Louie who tries to get Frankie to return to his heroin habit. ‘I ain’t dealin’ for nobody. I ain’t dealin’ for nobody no more’, Frankie tells tells Schwiefka insistently; but the odds are stacked against him, and given the pressures from Zosch, Schwiefka and Louie it isn’t long before Frankie is driven back to Schwiefka and his card games. Frankie is aware that returning to his old lifestyle will inevitably lead to him becoming hooked on junk again. He tells Zosch that Dr Lennox warned him, ‘If I lived when I got out, how I lived when I went in there, chances are I’d be hooked in no time’. Meeting with Sparrow for the first time after being released from prison, Frankie listens as Sparrow pleads with him: ‘Don’t start up with that peddler again’. ‘Me?’, Frankie quips, ‘I’d rather chop my arm off before I let him touch it’: given Frankie’s ‘golden’ arm and talent for both drumming and card dealing (and of course the fact that he mainlines the heroin into the vein in the crook of his arm), Frankie’s promise to ‘chop off my arm’ before he lets Louie touch it is rich with irony. Like all persistent peddlers, who are savvy to the laws of supply and demand that are the crux of any capitalist endeavour, Louie offers Frankie his first hit for free: ‘You broke? Now ain’t you being stupid: it’s for free’. Frankie protests that ‘I don’t need it, is all. I kicked it’. ‘Oh! Kicked it. One of “them”’, Louie observes. However, it isn’t long before Louie wears Frankie down; the first fix may be for free, but the price of subsequent hits goes up. ‘They keep raising the price on me’, Louie protests when Frankie asks why the cost of a fix has gone up from two dollars to five bucks. ‘They keep doing that, I’ll have to find something to take its place’, Frankie observes. ‘Monkey’s never dead, Dealer’, Louie tells him, ‘The monkey never dies. When ya kick him off, he just hides in a corner waitin’ his turn’. When Frankie’s need for a fix accelerates, Louie observes, ‘Beginning to wear off quick for you, ain’t it? You’re graduating, student. You need to step up’.  The sequences in which Frankie gets high still pack a punch: we see Frankie in Louie’s pad, tying a tie around his arm and using it as a tourniquet whilst Louie cooks the heroin in a spoon over a lit candle. Frankie takes the hit, a tight close-up of Sinatra’s eyes conveying the euphoria of the fix in a way that is far more effective than, say, a shot of the needle entering Frankie’s arm. ‘The monkey’ll die waitin’’, Frankie promises, ‘He ain’t climbin’ up on my back no more. Never again. I mean it’. ‘Sure, sure’, Louie responds with all the false sincerity of the dope peddler: he knows that Frankie will be back for another fix, and another, and another. Frankie promises himself that ‘I kicked it, and I’m not too far hooked to kick it again’, but the hollowness of his words resounds throughout the narrative. The sequences in which Frankie gets high still pack a punch: we see Frankie in Louie’s pad, tying a tie around his arm and using it as a tourniquet whilst Louie cooks the heroin in a spoon over a lit candle. Frankie takes the hit, a tight close-up of Sinatra’s eyes conveying the euphoria of the fix in a way that is far more effective than, say, a shot of the needle entering Frankie’s arm. ‘The monkey’ll die waitin’’, Frankie promises, ‘He ain’t climbin’ up on my back no more. Never again. I mean it’. ‘Sure, sure’, Louie responds with all the false sincerity of the dope peddler: he knows that Frankie will be back for another fix, and another, and another. Frankie promises himself that ‘I kicked it, and I’m not too far hooked to kick it again’, but the hollowness of his words resounds throughout the narrative.

Equally impactful is the prolonged sequence in which Frankie goes ‘cold turkey’ in Molly’s rooms. Molly mocks Frankie’s desperation for a fix, telling him sarcastically, ‘Why should you hurt like other people hurt? Yes, so you had a dog’s life with never a break. Why try to face it like other people do? No, just roll up all your pains into one big hurt, and then flatten it with a fix’. Making the decision to go cold turkey, Frankie makes Molly promise not to let him out of the room or to ‘try to help me with pills or dope or any stuff like that’. ‘Here we go, down and dirty’, Frankie asserts as Molly locks him in the room. We see Frankie, his helplessness communicated via high-angle shot of him as he writhes on the floor, clutching at his belly; Preminger even shows him using a sewing-needle to dry prick the vein in his arm. Brando was initially in the running to play Frankie but Sinatra took the role after Brando hesitated about it. Preminger initially wanted Barbara Bel Geddes to play Frankie’s wife Zosch, but gave the part to Eleanor Parker after being impressed with her performance in MGM’s biopic of Marjorie Lawrence, Interrupted Melody (Curtis Bernhardt, 1955). The part of Molly, meanwhile, went to Kim Novak, who Preminger hired from Columbia for $100,000 for five weeks’ work, reputedly unaware of Novak’s lack of formal training or experience in the field of screen acting. Novak’s lack of confidence meant that some scenes needed thirty or forty takes, but Preminger and Sinatra – two men known for their hot tempers – were patient with her (Hirsch, op cit.: np). Preminger later observed that ‘What I didn’t know at the time was that her [Novak’s] earlier movies had been dubbed afterwards because she could never get the lines right. I didn’t want to dub [….] She just had no self-confidence, none at all. She’d been treated like a nincompoop, but she’s really quite shrewd’ (Preminger, quoted in ibid.). Preminger ‘knew she was right for the part’ because Novak ‘has a sadness inside, just the quality I wanted, and I knew it would come through if we made her feel comfortable’ (Preminger, quoted in ibid.).  Preminger and Sinatra had an amicable working relationship, but Preminger clashed with Darren McGavin, playing the role of Frankie’s ‘pusher’ Louie. ‘I felt he was fighting himself, getting in his own way, and I treated him pretty rough’, Preminger later admitted (Preminger, quoted in ibid.). Preminger and McGavin reputedly had a major argument on the set, which resulted in Preminger telling the actor, ‘you’re a bad actor on stage, a bad actor in front of the camera’ (ibid.). However, McGavin later reflected on this incident, suggesting that Preminger could be ‘cruel and sadistic’ but that McGavin had ‘a tremendous liking for him. Besides, look at the results’ (McGavin, quoted in ibid.). Preminger and Sinatra had an amicable working relationship, but Preminger clashed with Darren McGavin, playing the role of Frankie’s ‘pusher’ Louie. ‘I felt he was fighting himself, getting in his own way, and I treated him pretty rough’, Preminger later admitted (Preminger, quoted in ibid.). Preminger and McGavin reputedly had a major argument on the set, which resulted in Preminger telling the actor, ‘you’re a bad actor on stage, a bad actor in front of the camera’ (ibid.). However, McGavin later reflected on this incident, suggesting that Preminger could be ‘cruel and sadistic’ but that McGavin had ‘a tremendous liking for him. Besides, look at the results’ (McGavin, quoted in ibid.).

Preminger once stated that ‘When a producer buys the rights to a book or a play he owns it […] The property rights are transferred, as in any sale. The writer gives up his control […] When I prepare a story for filming it is being filtered through my brain, my emotions, my talent such as I have … I have no obligation, nor do I try, to be “faithful” to the book’ (Preminger, quoted in Hirsch, op cit.: np). Preminger’s philosophy towards the process of adaptation is evident in The Man with the Golden Arm. Much to the chagrin of Algren, who felt that Preminger had ‘done violence’ to his story, Preminger made the protagonist of the story, Frankie Machine, more sympathetic than in Algren’s novel by depicting his wife as shrewd and exploitative of Frankie’s sense of responsibility towards her (Algren, quoted in ibid.). Preminger and his screenwriters also pushed Frankie’s addiction further to the forefront of the drama and concocted a far more ‘Hollywood’ ending to the narrative. In the novel, Frankie Machine is a war veteran who first became hooked on morphine after suffering an injury during his military service. However, Preminger’s film dispensed with the novel’s examination of Frankie’s military background, which within Algren’s narrative established a context for his addiction, and changed Frankie’s drug of choice from morphine to heroin (although the drug itself isn’t actually named within the film’s dialogue). By removing the novel’s discussion of Frankie’s war injury, Preminger’s film doesn’t provide a ‘reason’ for Frankie’s addiction to heroin other than Frankie’s frustration with his life and the slimy approach of the dope peddler Louie.  Though set in Chicago, and Preminger apparently initially wanted much of the film to be shot on location, the picture is clearly shot on a sound studio – with the exteriors shot on RKO’s backlot. The fact that the film was shot on a sound stage is noticeable, with the exterior sequences feeling unconvincing, strangely lacking in passing pedestrians and narrow in their field of view, but the decision not to shoot on location helped Preminger complete the film without going over budget and very slightly ahead of schedule (Hirsch, op cit.: np). Though set in Chicago, and Preminger apparently initially wanted much of the film to be shot on location, the picture is clearly shot on a sound studio – with the exteriors shot on RKO’s backlot. The fact that the film was shot on a sound stage is noticeable, with the exterior sequences feeling unconvincing, strangely lacking in passing pedestrians and narrow in their field of view, but the decision not to shoot on location helped Preminger complete the film without going over budget and very slightly ahead of schedule (Hirsch, op cit.: np).

Aubrey Malone has suggested that ‘The Man with the Golden Arm did for drug addiction what The Lost Weekend (1945) had done for alcoholism. It gave it a window, bringing it out into the open as a topic for discussion’ (Malone, 2011: 93). Although Preminger cut from the film a scene depicting Frankie Machine ‘cooking’ his heroin in a spoon, the film’s frank exploration of heroin addiction and direct challenge to the paradigms set in place by the Production Code led to controversy, with the Production Code Authority describing the picture as ‘fundamentally in violation of the code clause which prohibits pictures dealing with drug addiction’ (quoted in Lewis, 2000: 113). Facilitated by the 1948 anti-trust laws which enabled independent cinemas to show films (often foreign pictures) without Production Code Authority seals of approval, United Artists eventually distributed the picture minus the seal of approval of the PCA, resulting in a $25,000 fine. The decision to deny the film a seal of approval was reputedly made under pressure from Harry Ainslinger, the US narcotics commissioner; a seal from the PCA wouldn’t be granted to the film until 1962 (ibid.). (It was the second film Preminger made for United Artists to be released without a seal of approval from the PCA: the first was The Moon is Blue, released in 1953.) After the release of The Man with the Golden Arm, the Production Code would be altered to allow films to include references to drug addiction. The commercial successes of both The Moon is Blue and The Man with the Golden Arm ‘showed everyone that both the PCA and the Legion of Decency could be defied successfully if the film was good enough, and played to audiences’ sensitivities’ (Malone, op cit.: 92). The film is uncut and runs for 119:05 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 21Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The presentation is in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio. Though some shots are very tightly composed, it seems the film was intended to be seen 'wide'. (The film has also been released on Blu-ray in Germany, with a 2007 restoration by TLE Films, in the 1.37:1 ratio.) Taking up approximately 21Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The presentation is in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio. Though some shots are very tightly composed, it seems the film was intended to be seen 'wide'. (The film has also been released on Blu-ray in Germany, with a 2007 restoration by TLE Films, in the 1.37:1 ratio.)

No details about the source for this release were available to us, but the film’s negative apparently no longer exists. The film is in the public domain in America and has seen many sub-par DVD releases in that territory. This new Blu-ray from Network is a drastic improvement over those presentations, with a fairly good sense of depth to the monochrome image and the level of detail a clear step above what is offered by those grey market DVDs. However, contrast levels seem a little ‘hot’ in places, with the details in Sinatra’s white shirts often burnt-out and, curiously, mid-tones being oddly ‘flat’ in some shots (eg, when Frankie first steps off the bus in Chicago, the tones of Sinatra’s face and those of the bus’ paintwork behind him are virtually indistinguishable). Organic film grain is present but sometimes seems ‘crushed’ by the encode, with the effect that fine detail sometimes seems 'smoothed out'. (Thought it's also possible that some form of noise reduction has been applied to the image, resulting in this appearance.) It’s a decent enough presentation, definitely ahead of the DVDs that are available, but there’s room for further improvement. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track (in English, naturally) which has optional English subtitles to accompany it. Though dialogue is clear throughout, the audio track doesn’t have much range and is very bassy and slightly ‘muddy’ or distorted because of it: sometimes the film sounds as if it’s playing underwater.

Extras

The film is accompanied by an image gallery (2:28) containing posters, colourised lobby cards and press stills.

Overall

Despite Algren’s dissatisfaction with Preminger’s film adaptation of his novel, The Man with the Golden Arm is an eminently watchable picture, largely thanks to Sinatra’s performance, which Gary Giddins has described as ‘alternately jumpy and smooth, perversely innocent, whistling past the graveyard of his ambition, yet ready at the hint of an obstacle to get mislaid in drugs. His skin tingles and he is racked with guilt, and he lets us see the desperation with naked clarity’ (Giddins, 2010: 175). (However, as a fan of McGavin, I have to say that he’s a delight in the role of the slimy, manipulative Louie.) Novak is much better in her role than is often claimed; but though Eleanor Parker is an excellent actress, Zosch comes across as little more than a cardboard cutout from a misogynist’s nightmare: a shrill, manipulative harridan whose self-interest is arguably the ultimate engine behind Frankie’s return to addiction. Despite Algren’s dissatisfaction with Preminger’s film adaptation of his novel, The Man with the Golden Arm is an eminently watchable picture, largely thanks to Sinatra’s performance, which Gary Giddins has described as ‘alternately jumpy and smooth, perversely innocent, whistling past the graveyard of his ambition, yet ready at the hint of an obstacle to get mislaid in drugs. His skin tingles and he is racked with guilt, and he lets us see the desperation with naked clarity’ (Giddins, 2010: 175). (However, as a fan of McGavin, I have to say that he’s a delight in the role of the slimy, manipulative Louie.) Novak is much better in her role than is often claimed; but though Eleanor Parker is an excellent actress, Zosch comes across as little more than a cardboard cutout from a misogynist’s nightmare: a shrill, manipulative harridan whose self-interest is arguably the ultimate engine behind Frankie’s return to addiction.

There’s a wonderful sense of irony within the film’s approach to its material: the ‘golden arm’ reference within the title has a plurality of meanings – referring to Frankie’s apparently innate skill at drumming, his ‘golden’ talent as a dealer for the house in Schwiefka’s card games, and his habit of mainlining heroin (‘gold’, or the ‘golden girl’) into his arm (with the lethal shooting of pure heroin often being referred to as a ‘golden shot’). The profound irony of Frankie’s attitudes towards his own addiction and his criticism of Molly’s new lover Johnny as ‘a habitual drunk’ is underscored when Molly reminds Frankie that ‘Everybody’s an habitual something’. Preminger claimed the film offered ‘a very moral lesson’ and was ‘a warning against the consequences of taking narcotics’ (Preminger, quoted in Malone, 2011: 92). The anti-drugs stance of the film is very clear, despite its slightly ‘Hollywood’ approach to Algren’s gritty novel. This disc contains a reasonably good presentation of the film which, whilst not perfect, is clearly an improvement on the various DVD releases. References: Giddins, Gary, 2010: Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. New York: W W Norton & Company Hirsch, Foster, 2011: Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King. Knopf Doubleday Lewis, Jon, 2000: Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry. New York University Malone, Aubrey, 2011: Censoring Hollywood: Sex and Violence in Film and on the Cutting Room Floor. London: McFarland Simon, Daniel M, 1996: ‘Appendix [Foreword]’. In: Algren, Nelson, 1996: Nonconformity: Writing on Writing. Seven Stories Press: 113-4 This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|