|

|

Second Fiddle

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st July 2015). |

|

The Film

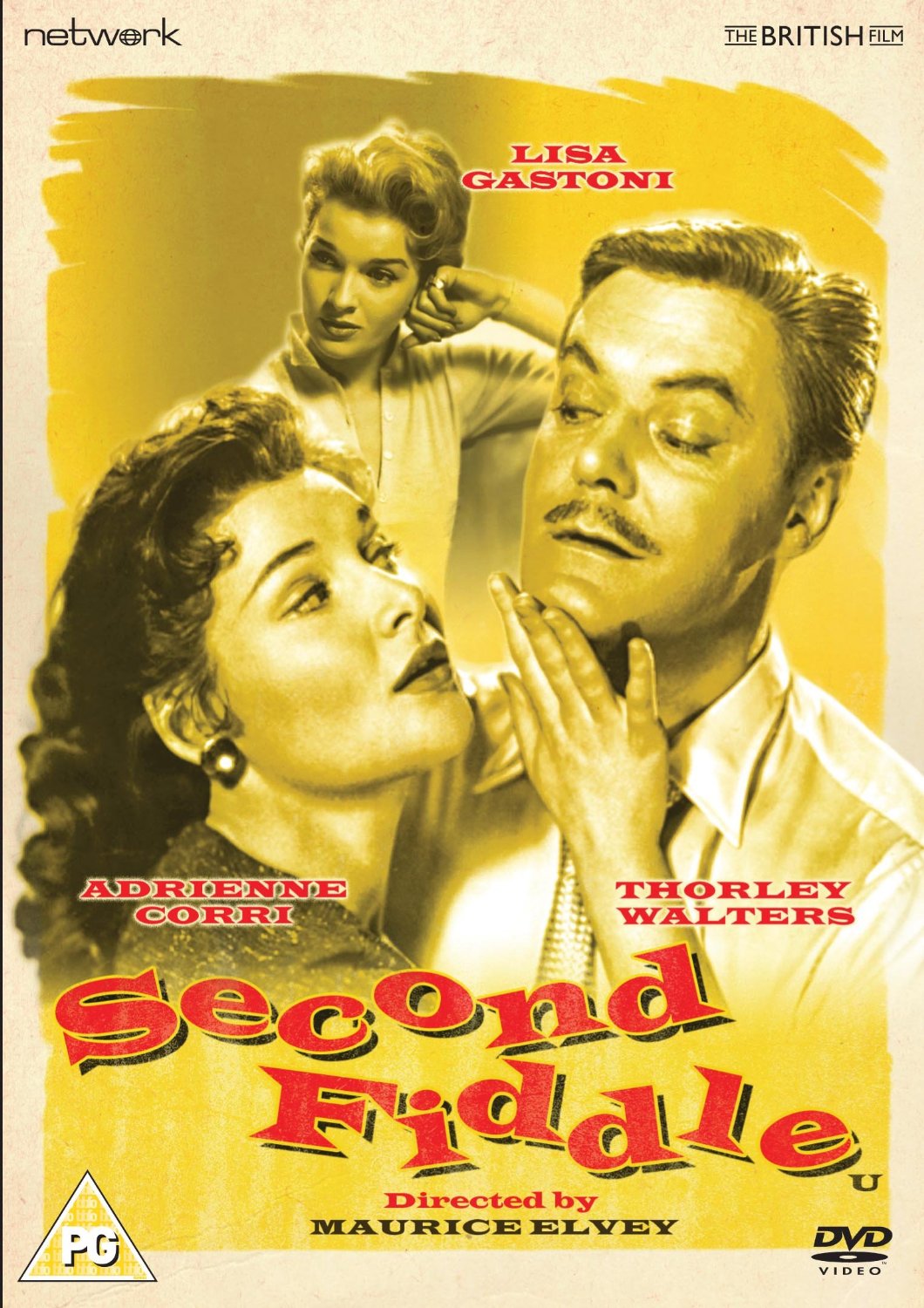

Second Fiddle (Maurice Elvey, 1957) Second Fiddle (Maurice Elvey, 1957)

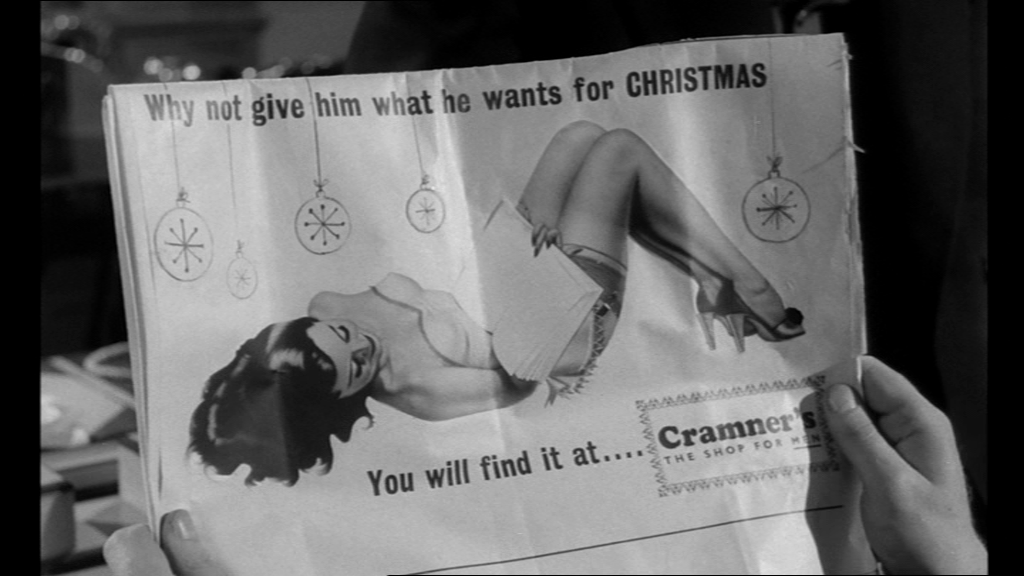

The final film of veteran director Maurice Elvey, Second Fiddle (1957) was until recently on the British Film Institute’s ’75 Most Wanted’ list: a list of seventy-five British films whose film elements were considered ‘lost’. Its director Maurice Elvey is considered the most prolific film director in the history of British cinema, having directed almost two hundred features and short films during his filmmaking career, which began in 1913 and was ended in 1957 by Elvey’s failing eyesight. Leo Enticknap has stated that Elvey’s reputation ‘as a prolific but minor talent’ is ‘well-established’, with Elvey’s work often falling in the shadow of the work of his contemporary, Alfred Hitchcock (Enticknap, 2013: 37). In his biography of David Lean, Gene Phillips suggests that Elvey, on whose film The Quinneys (1927) Lean worked as a camera assistant (Lean’s first job in cinema), was at the time considered ‘as a perfunctory filmmaker who directed any script that was handed to him. He was little more than an average hack’ (Phillips, 2006: 18). The actress Rosamund John ‘described him [Elvey] as a pompous little man with a pince-nez whose manner belied the fact that he was basically indecisive’ and sometimes ‘could not decide which take to print after a scene’ (ibid.). On the other hand, Elvey impressed Lean, who once stated that Elvey ‘was very effective and did some excellent pictures’ (Lean, quoted in ibid.). Although Elvey worked in a wide variety of genres, his earlier pictures were largely biopics or adaptations of Victorian novels, and towards the end of his time as a director Elvey tended to favour dramas and comedies. Elvey’s earlier films feature some strong location work and handling of crowd scenes, as evidenced in The Life Story of David Lloyd George (Elvey, 1918); this something which is sadly absent in his studio-bound final film, Second Fiddle.  Second Fiddle takes the form of a comedy about the workplace, in this case the Pontifex Advertising Agency, and the new marriage between two of its employees, Charles (Thorley Walters) and Deborah (Adrienne Corri). The film begins as a printing mix-up in one of the company’s ads has led to an image intended to advertise a new line of ladies’ tights – depicting a young woman in a reclining pose, her nylon-clad legs on display – being married to the text (‘Why not give him what he wants for Christmas?’) of an ad for a men’s clothes shop owned by the agency’s valued client Harold Cramer. Cramer threatens to withdraw his allegiance with the Pontifex Advertising Agency, and the responsibility for assuaging Cramer’s concerns falls on the shoulders of Charles. Attempting to pacify Cramer, Charles discovers that surprisingly, the advert has been incredibly successful, and Cramer is now profoundly pleased with it, promising to ‘spend an extra six thousand quid on a new campaign’ – as Charles boasts when he returns from his sit-down with Cramer. Second Fiddle takes the form of a comedy about the workplace, in this case the Pontifex Advertising Agency, and the new marriage between two of its employees, Charles (Thorley Walters) and Deborah (Adrienne Corri). The film begins as a printing mix-up in one of the company’s ads has led to an image intended to advertise a new line of ladies’ tights – depicting a young woman in a reclining pose, her nylon-clad legs on display – being married to the text (‘Why not give him what he wants for Christmas?’) of an ad for a men’s clothes shop owned by the agency’s valued client Harold Cramer. Cramer threatens to withdraw his allegiance with the Pontifex Advertising Agency, and the responsibility for assuaging Cramer’s concerns falls on the shoulders of Charles. Attempting to pacify Cramer, Charles discovers that surprisingly, the advert has been incredibly successful, and Cramer is now profoundly pleased with it, promising to ‘spend an extra six thousand quid on a new campaign’ – as Charles boasts when he returns from his sit-down with Cramer.

Meanwhile, Charles’ fiancée Deborah worries about her future with the company, which has a rule about not employing married women. Deb is concerned that when she and Charles marry, she will be out of a job. Charles appears to be conflicted about the company’s policy of not employing married women, wanting to support Deb but not wishing to be seen to have his masculinity undermined by the financial independence of his wife. However, the company eventually reverses its policy in relation to this matter, enabling a newly-wed Deb to continue working. When Deb is given the job of overseeing a lucrative campaign in New York City, and Charles seems to be overlooked for a promotion he believed would be his, Charles sees his masculinity as being placed in question. Whilst Deb is away in New York, Charles finds himself involved in a flirtatious relationship with another of the company’s female employees, his pretty secretary Pauline (Lisa Gastoni). The film’s comedic examination of Charles and Deb’s relationship is framed against an astute and interesting examination of gender politics within the workplace. In many ways, the ad agency setting and the focus on gender relations invite easy comparisons with the recent, lauded American television series Mad Men (AMC, 2007-15). Like that series, Elvey’s approach to these issues is objective and laced with irony. Within the fllm, jokes are made about the company’s policy of not hiring married women. ‘No-one in his right mind would employ a married woman’, one of the employees asserts. ‘Well, I think married women should be compulsory’, Bill Turner responds, ‘I’d bar single women; keep them out of the office altogether’. ‘Why?’, Turner is asked. ‘Keep the place safe for bachelors’, Turner responds. Later, a young male employee jokes, ‘Well, I hope they don’t change the rule [….] It’s better as it is for us bachelors: plenty of single girls to choose from’. Meanwhile, the idea of a man ‘allowing’ his wife to continue working is seen as a slight against his masculinity: just before Charles and Deb are shown, via montage, getting married and then having their honeymoon in France, we see some of the employees discussing the company’s about-face towards their policy of not hiring married women, making a joking toast ‘To wives who earn their husbands’ beer money’. The sentiment is echoed in the lyrics of the jaunty song that plays out over the film’s opening titles (‘No self-respecting fellow / Lets the lady take the wheel / So I won’t play second cello / Not for all your sex appeal’).  Deb and Charles find themselves at odds with regards the company’s policy of not hiring married women. Deb wishes to continue working as a copywriter; though outwardly criticising the company’s policy, Charles submits to the patriarchal notion that men should be breadwinners. ‘Well, of course we should employ married women’, Charles tells Deb during a conversation in their favourite haunt, the Tahiti coffee house, ‘but if Nixon gives me this rise, well, you won’t have to work after we’re married’. ‘Hmm’, Deb responds, ‘I’m beginning to think your views aren’t as advanced as you pretend’. Later in the film, when Deb is given the job of overseeing the big television advertising campaign with which Pontifex has become engaged in New York, Charles discovers (or at least believes) that he has not received the promotion for which he hoped. ‘I should never have got married until I was earning enough money to keep us both’, Charles grumbles, declaring that the situation ‘makes me a miserable sponger living here in your [Deb’s] home’. Deb and Charles find themselves at odds with regards the company’s policy of not hiring married women. Deb wishes to continue working as a copywriter; though outwardly criticising the company’s policy, Charles submits to the patriarchal notion that men should be breadwinners. ‘Well, of course we should employ married women’, Charles tells Deb during a conversation in their favourite haunt, the Tahiti coffee house, ‘but if Nixon gives me this rise, well, you won’t have to work after we’re married’. ‘Hmm’, Deb responds, ‘I’m beginning to think your views aren’t as advanced as you pretend’. Later in the film, when Deb is given the job of overseeing the big television advertising campaign with which Pontifex has become engaged in New York, Charles discovers (or at least believes) that he has not received the promotion for which he hoped. ‘I should never have got married until I was earning enough money to keep us both’, Charles grumbles, declaring that the situation ‘makes me a miserable sponger living here in your [Deb’s] home’.

Meanwhile, the policy of not hiring married women is debated at the meetings of the company’s directors. When the blame for the mix-up over the Cramer account first surfaces, before the company’s directors have been informed of Cramer’s about-face on the event, the blame is leveled at one of the company’s older female employees, Fenny (Madoline Thomas). An ageing spinster, Fenny has recently been pushed into a role of additional responsibility for which, the directors believe, she is ill-prepared. ‘You can’t fire Fenny, but you can retire her’, Mr Pontifex (Laurence Maraschal) declares during the meeting – a sentiment that is probably deeply shocking to modern sensibilities. Pontifex even suggests that ‘It seems to me that Fenny could have switched these ads as a protest, as a suffragette demonstration. In that case, the woman should be fired’. When the clause about the company not hiring married women is mentioned, Pontifex asserts, ‘Nonsense! You’ll not get me to talk on that again. I refuse to waste my time on married women’. However, as he is reminded, the hiring of married women makes sense economically: ‘Two out of three women on this staff get married after eighteen months’, Pontifex is told, ‘and then are forced to leave; forced to leave by us, gentlemen’. Many of these, mostly young, women are trained by Pontifex and fired when they get married – eventually going on to work for one of the firm’s competitors.  The film contains a comical depiction of workplace politics, attitudes that will be recognisable to many of the film’s viewers. When the mix-up involving the ad for Harold Cramer’s clothes shop is discovered, the buck is passed from one employee to the next, until it lands squarely on the shoulders of Charles. Mr Nathan asks his underling Bill Turner (Richard Wattis) to pacify Cramer, telling him that ‘You’ve got to convince Cramer that the whole thing’s good, harmless fun’; in turn, Turner, delegates this responsibility to Carter (Brian Nissen), one of the ‘ideas men’, repeating the words Nathan spoke to him (‘Tell him [Cramer] it was all good, clean fun’, Turner tells Carter); finally, Carter, approaches Charles and suggests that it is Charles’ responsibility to pacify Cramer. The picture’s subtle and ironic examination of workplace politics makes it a joy to watch. The film contains a comical depiction of workplace politics, attitudes that will be recognisable to many of the film’s viewers. When the mix-up involving the ad for Harold Cramer’s clothes shop is discovered, the buck is passed from one employee to the next, until it lands squarely on the shoulders of Charles. Mr Nathan asks his underling Bill Turner (Richard Wattis) to pacify Cramer, telling him that ‘You’ve got to convince Cramer that the whole thing’s good, harmless fun’; in turn, Turner, delegates this responsibility to Carter (Brian Nissen), one of the ‘ideas men’, repeating the words Nathan spoke to him (‘Tell him [Cramer] it was all good, clean fun’, Turner tells Carter); finally, Carter, approaches Charles and suggests that it is Charles’ responsibility to pacify Cramer. The picture’s subtle and ironic examination of workplace politics makes it a joy to watch.

The film runs for 70:37 mins (PAL) and appears to be intact, though it’s worth noting that BBFC’s website cites the film’s running time when submitted to the BBFC in 1957 as just over 77 mins – which is about three minutes longer than the version presented here (when PAL speedup has been taken into account). The reason for this discrepancy is at this juncture unclear.

Video

The film is presented in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement – which would seem to be the intended aspect ratio, or as near-as-dammit. The film’s monochrome photography is served well by the presentation: the image is clear, with a good level of detail and strong contrast levels, with good definition in the mid-tones. There is some minor damage here and there – but remarkably little of this, given the film’s rarity.

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track (in English, naturally). Dialogue is clear throughout, although the track contains some very slight distortion here and there. Sadly, no subtitles are provided.

Extras

The disc’s sole extra is a stills gallery (0:31) containing promotional imagery.

Overall

As noted above, comparisons may easily be drawn between Second Fiddle and the recent US television series Mad Men, in terms of the film’s exploration of the relationships between gender politics in the workplace and at home, its advertising agency setting and the script’s ironic approach to this material. It’s a film that is photographed in a very static way, in a studio setting (Shepperton Studios) and with much use of long takes and theatrical ‘side-on’ blocking of actors – but this fits the material like a glove. It’s a funny, enjoyable film which also slyly comments on issues of gender at work and at home. Whilst, given the its ‘lost’ status, the film could perhaps have benefited from some contextual material, this DVD release from Network contains a tip-top presentation of the film. As noted above, comparisons may easily be drawn between Second Fiddle and the recent US television series Mad Men, in terms of the film’s exploration of the relationships between gender politics in the workplace and at home, its advertising agency setting and the script’s ironic approach to this material. It’s a film that is photographed in a very static way, in a studio setting (Shepperton Studios) and with much use of long takes and theatrical ‘side-on’ blocking of actors – but this fits the material like a glove. It’s a funny, enjoyable film which also slyly comments on issues of gender at work and at home. Whilst, given the its ‘lost’ status, the film could perhaps have benefited from some contextual material, this DVD release from Network contains a tip-top presentation of the film.

References: Phillips, Gene D, 2006: Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. The University Press of Kentucky Enticknap, Leo, 2013: Film Restoration: The Culture and Science of Audiovisual Heritage. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|