|

|

Contamination AKA Alien Contamination (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (6th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Contamination (Luigi Cozzi, 1980) Contamination (Luigi Cozzi, 1980)

Italian cinema’s dedication to the filone principle, especially since the mid-1960s, has been widely discussed and documented: for many English-language fans of Italian cinema, the most identifiable filoni (or artistic currents/‘veins’) within Italian cinema from that era include the western all’italiana (Italian-style Western, or Continental/Spaghetti Western), pepla (‘sword-and-sandal’ films), ‘mondo’ pictures, ‘nunsploitation’ films, the thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thrillers, or gialli all’italiana), the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films, or poliziotteschi) and, of course, the Italian zombie films – such as Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (1979) – that were released in the wake of the success of George A Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). However, there were of course lots of other, less high-profile (at least, for non-Italian audiences) filoni, including musicarelli (song-and-dance films), the fumetti neri (comic book-style films such as Mario Bava’s Diabolik, 1968; and Umberto Lenzi’s Kriminal, 1966), and the Carry On-style sex comedies (the commedia sexy all’italiana) ‘which deal with impotence, sterility, dominant women, insatiable women and sexual hang-ups’ (Nakahara, 2013: 99). (These filoni were arguably the ones which didn’t translate as well to non-domestic audiences, which perhaps explains why they’re less frequently discussed outside Italy.) The filone principle was dictated by Italian cinema’s need to increase its audience and promote itself as a viable alternative to Hollywood cinema. This led to a split between Italian films that were produced and consumed as examples of ‘art’ cinema (for example, the works of filmmakers like Fellini and Pasolini), and those which were intended to capitalise on, or exploit, popular trends. Sometimes these two tendencies in Italian cinema overlapped, as was the case with the spate of commedia sexy films with historical, often medieval, settings which followed the production of Pasolini’s ‘Trilogy of Life’ (Il Decameron/The Decameron, 1971; I racconti di Canterbury/The Canterbury Tales, 1972; and Il fiore delle mille e un notte/Arabian Nights, 1974) (see ibid.).  Although a filone could develop from a popular domestic ‘hit’, they also often developed from a Hollywood film which had achieved recognisable success within the Italian market. Luigi Cozzi once remarked that in ‘Italy, when you bring a script to a producer, the first question he asks is not “what is your film like?” but “what film is your film like?” That’s the way it is, we can only make Zombi 2, never Zombi 1’ (Cozzi, quoted in Baschiera & Di Chiara, 2010: 106). Towards the end of the ‘dream’ of Italian popular cinema – as New Hollywood cinema increased its stranglehold on production, distribution and exhibition with the ‘blockbuster’ ethos that followed the releases of films such as Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) – Italian filmmakers experimented with mimicking the aesthetic of these big budget Hollywood ‘blockbusters’. Previous filoni had flourished within the Italian film industry, the limited resources (in comparison with Hollywood) having little negative impact on the films’ narratives – in fact, in many cases, often offering an alternative to Hollywood cinema that had its own unique ‘flavour’ (for example, the now-iconic use of locations in Almeria in many westerns all’italiana, or the depiction of Italian cities – and, less frequently, rural spaces – in the thrilling all’italiana films of the 1960s and 1970s). However, as Hollywood cinema during the 1970s became increasingly focused on elaborate moments of spectacle, lacking the resources of their Hollywood brethren the Italian imitators of New Hollywood pictures such as Star Wars often look slightly cheap and tawdry by comparison (for example, Aldo Lado’s L’umanoide/The Humanoid, 1979). This was emphasised in the Italian films that aped Hollywood trends but tried to establish their difference from their Hollywood models by ‘upping the ante’ in terms of sexual content: for example, La bestia nello spazio (The Beast in Space, 1980), Alfonso Brescia’s curious, pornographic hybrid of Walerian Borowczyk’s La bête (The Beast, 1975) and Star Wars; or many of the Italian ‘demonic intercession’ films that mimicked the paradigms of American horror pictures such as The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) and The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) and married themes of demonic possession with explicit sexual content (for example, Mario Bianchi’s La bimba di Satana/Satan’s Baby Doll, 1982; Andrea Bianchi’s Malabimba, 1979; and Franco Lo Cascio & Angelo Pannacciò’s Un urlo dalle tenebre/Cries and Shadows, 1975). Sometimes this impression of ‘cheapness’ is mitigated by the films’ sense of humour, as is arguably the case with Luigi Cozzi’s Starcrash (1978) – which, in its use of stop-motion animation, looks as much to the work of Ray Harryhausen for inspiration as it does to Star Wars. Nevertheless, it’s probably fairly safe to say that by foregrounding moments of spectacle enabled by the resources available to it, Hollywood cinema of this period offered a model which local cinemas found difficult to emulate, something later Italian films modeled on Hollywood blockbusters foreground to an even greater degree (for example, Bruno Mattei’s Aliens/Terminator pastiche Terminator 2: Shocking Dark, 1989, and the Predator imitation Robowar, 1988). Although a filone could develop from a popular domestic ‘hit’, they also often developed from a Hollywood film which had achieved recognisable success within the Italian market. Luigi Cozzi once remarked that in ‘Italy, when you bring a script to a producer, the first question he asks is not “what is your film like?” but “what film is your film like?” That’s the way it is, we can only make Zombi 2, never Zombi 1’ (Cozzi, quoted in Baschiera & Di Chiara, 2010: 106). Towards the end of the ‘dream’ of Italian popular cinema – as New Hollywood cinema increased its stranglehold on production, distribution and exhibition with the ‘blockbuster’ ethos that followed the releases of films such as Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) and Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) – Italian filmmakers experimented with mimicking the aesthetic of these big budget Hollywood ‘blockbusters’. Previous filoni had flourished within the Italian film industry, the limited resources (in comparison with Hollywood) having little negative impact on the films’ narratives – in fact, in many cases, often offering an alternative to Hollywood cinema that had its own unique ‘flavour’ (for example, the now-iconic use of locations in Almeria in many westerns all’italiana, or the depiction of Italian cities – and, less frequently, rural spaces – in the thrilling all’italiana films of the 1960s and 1970s). However, as Hollywood cinema during the 1970s became increasingly focused on elaborate moments of spectacle, lacking the resources of their Hollywood brethren the Italian imitators of New Hollywood pictures such as Star Wars often look slightly cheap and tawdry by comparison (for example, Aldo Lado’s L’umanoide/The Humanoid, 1979). This was emphasised in the Italian films that aped Hollywood trends but tried to establish their difference from their Hollywood models by ‘upping the ante’ in terms of sexual content: for example, La bestia nello spazio (The Beast in Space, 1980), Alfonso Brescia’s curious, pornographic hybrid of Walerian Borowczyk’s La bête (The Beast, 1975) and Star Wars; or many of the Italian ‘demonic intercession’ films that mimicked the paradigms of American horror pictures such as The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) and The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) and married themes of demonic possession with explicit sexual content (for example, Mario Bianchi’s La bimba di Satana/Satan’s Baby Doll, 1982; Andrea Bianchi’s Malabimba, 1979; and Franco Lo Cascio & Angelo Pannacciò’s Un urlo dalle tenebre/Cries and Shadows, 1975). Sometimes this impression of ‘cheapness’ is mitigated by the films’ sense of humour, as is arguably the case with Luigi Cozzi’s Starcrash (1978) – which, in its use of stop-motion animation, looks as much to the work of Ray Harryhausen for inspiration as it does to Star Wars. Nevertheless, it’s probably fairly safe to say that by foregrounding moments of spectacle enabled by the resources available to it, Hollywood cinema of this period offered a model which local cinemas found difficult to emulate, something later Italian films modeled on Hollywood blockbusters foreground to an even greater degree (for example, Bruno Mattei’s Aliens/Terminator pastiche Terminator 2: Shocking Dark, 1989, and the Predator imitation Robowar, 1988).

Nevertheless, within this context Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) fired the imagination of a number of filmmakers, and saw imitators not only in Italy but also in American independent cinema (Bruce D Clark’s Galaxy of Terror, 1981; Peter Clark’s The Intruder Within, 1981; and William Malone’s Titan Find, 1985) and Britain (Norman J Warren’s Inseminoid, 1981; and Harry Bromley Davenport’s Xtro, 1982). Many of these films took from Scott’s picture the iconography of the alien egg, the premise of human beings being ‘impregnated’ by an alien species (and subsequently exploding or otherwise giving birth to an alien creature) and, of course, the xenomorph itself. Kim Newman has suggested that the ‘graphic vision of the monster tearing its way out of a human shell’ was the boldest element that Alien added to the iconography of 1980s fantasy films: this imagery found its way into films as diverse as The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982) and Amityville II: The Possession (Damiano Damiani, 1982). Prior to the production of Contamination (1980), writer-director Luigi Cozzi – a lifelong science-fiction fan – began with an idea for a film inspired by Alien and, specifically, ‘the monster and the egg’ (Cozzi, in the featurette ‘Luigi Cozzi on Contamination’, included on this Blu-ray release). In making Contamination, Cozzi attempted to meld the iconography of Alien with some of the ideas contained within some of his favourite science-fiction films from previous eras, such as both versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel’s 1956 original and Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake) and Quatermass 2 (Val Guest, 1957). From the former, Cozzi took the idea of mind-controlled humans growing and harvesting the eggs/‘pods’, and from the latter he took the imagery of the villains in gas masks (translated in Cozzi’s film into white haz-mat suits) and the depiction of the aliens being in control of people in authority. Kim Newman has suggested that Contamination is ‘the best of the Italian Alien pseudo-sequels’ and is also ‘unique in choosing to rip off Quatermass 2 (1958) with its unscrupulous capitalists from outer space’ (Newman, 2011: 237). In the interview included on the 2003 DVD release of Contamination by Blue Underground, Cozzi has also suggested that the producers encouraged him to build into the film a James Bond-style espionage plot (which sees the film’s heroes infiltrating a coffee plant in Colombia) and include some elements from James Bridges’ The China Syndrome (1979).  The commercial successes of Alien and Star Wars convinced the Italian producers to bankroll Contamination, though Cozzi suggests that science-fiction movies have traditionally been difficult to make in Italy ‘because producers, who are usually older, don’t like this genre’ and it isn’t a huge hit with Italian audiences either – though the films often do well in overseas markets (‘Luigi Cozzi on Contamination). Contamination reputedly entered preproduction under the working title ‘Alien arriva sulla Terra’ (‘Alien Arrives on the Earth’), a moniker which made the connections between the film and Ridley Scott’s Alien even more transparent – as if the aping of elements of the iconography of Scott’s film wasn’t enough to do so already. (In Spain, Contamination was actually released under a similar title, as Contaminación: Alien Invade la Tierra/Contamination: Alien Invades the Earth.) However, this working title was abandoned after another Italian Alien clone was released under a very similar name in 1980: Ciro Ippolito’s Alien 2 sulla Terra (Alien 2: On Earth) (see Fischer, 2000: 141). A proposed Italian riff on James Bridges’ The China Syndrome, which was to have been directed by Lucio Fulci, had recently fallen by the wayside; this film, for which preproduction artwork had already been drawn up, was to have been titled Contamination: Atomic Project. Cozzi has suggested that the producers of Contamination saw the preproduction artwork for the abandoned Fulci film and decided to use the ‘Contamination’ title for their own production (Cozzi, cited in ibid.). The commercial successes of Alien and Star Wars convinced the Italian producers to bankroll Contamination, though Cozzi suggests that science-fiction movies have traditionally been difficult to make in Italy ‘because producers, who are usually older, don’t like this genre’ and it isn’t a huge hit with Italian audiences either – though the films often do well in overseas markets (‘Luigi Cozzi on Contamination). Contamination reputedly entered preproduction under the working title ‘Alien arriva sulla Terra’ (‘Alien Arrives on the Earth’), a moniker which made the connections between the film and Ridley Scott’s Alien even more transparent – as if the aping of elements of the iconography of Scott’s film wasn’t enough to do so already. (In Spain, Contamination was actually released under a similar title, as Contaminación: Alien Invade la Tierra/Contamination: Alien Invades the Earth.) However, this working title was abandoned after another Italian Alien clone was released under a very similar name in 1980: Ciro Ippolito’s Alien 2 sulla Terra (Alien 2: On Earth) (see Fischer, 2000: 141). A proposed Italian riff on James Bridges’ The China Syndrome, which was to have been directed by Lucio Fulci, had recently fallen by the wayside; this film, for which preproduction artwork had already been drawn up, was to have been titled Contamination: Atomic Project. Cozzi has suggested that the producers of Contamination saw the preproduction artwork for the abandoned Fulci film and decided to use the ‘Contamination’ title for their own production (Cozzi, cited in ibid.).

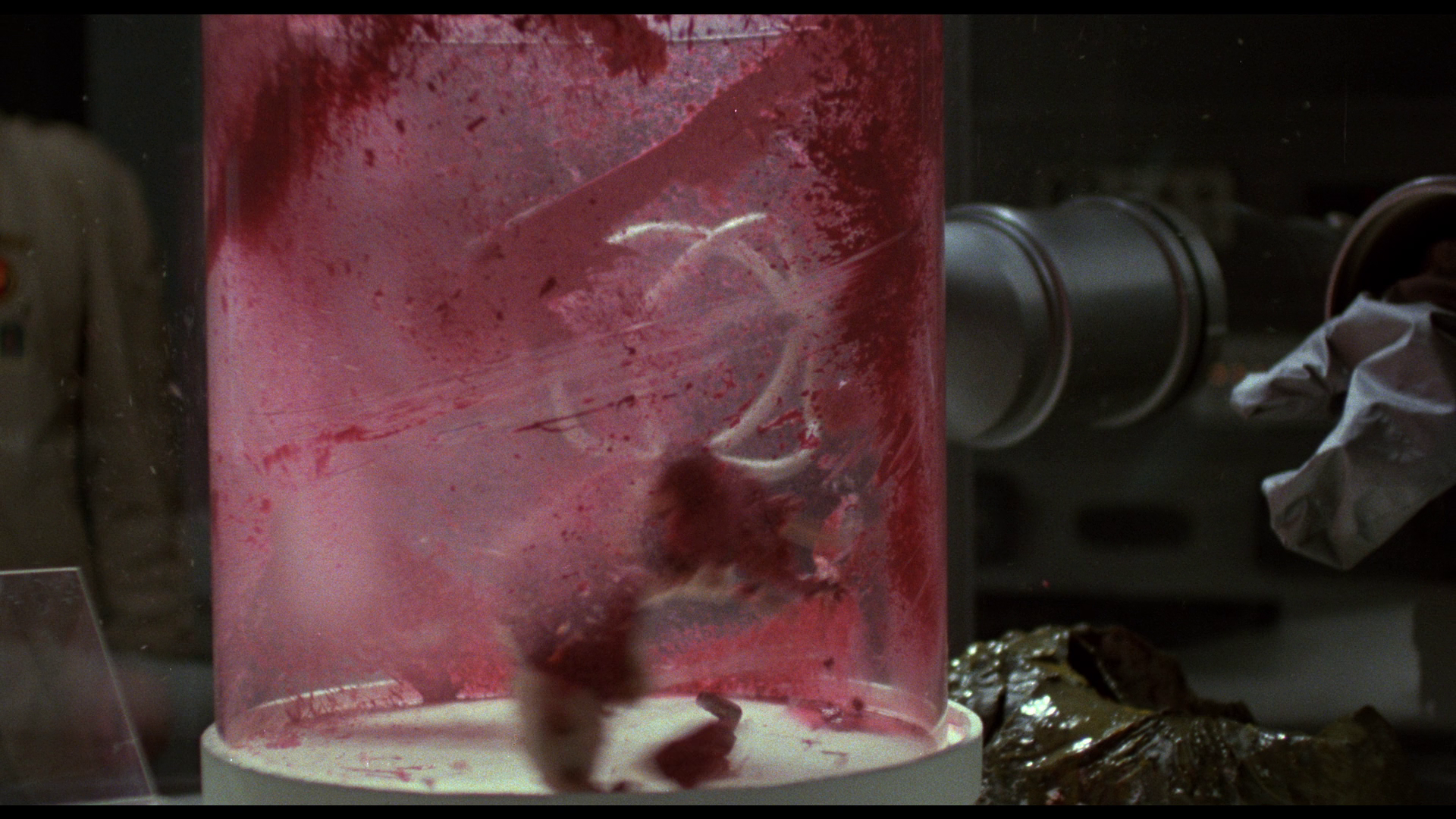

The film opens with an apparently abandoned large container ship, the Caribbean Lady, being towed into an empty dock in New York’s harbour. There, the Caribbean Lady is boarded by a team led by police lieutenant Tony Aris (Marino Masé) and scientific consultant Dr Turner (Carlo Monni), who discover the putrefying corpse of the ship’s captain stuffed into one of the cabins (‘It looks as if he’s been torn apart’, Turner observes helpfully) and, further into the ship, another corpse that is described in the dialogue as ‘literally in pieces’. In its hold, the ship is carrying containers marked with the brand ‘UniverX’; the containers apparently contain a strain of Colombian coffee. However, on closer inspection it seems that the boxes labeled as containing coffee are in fact filled with strange, green, rugby ball-sized eggs. ‘They look like giant pumpkins or some strange kind of fruit’, Turner suggests. One of the eggs, laying near some heating pipes, is pulsing and emitting a curious sighing sound. Eventually, it bursts, spewing a green substance on the faces of the men who are closest to it; this in turn causes the men to explode from within (in spectacular slow-motion).  Colonel Stella Holmes (Louise Marleau) is called in to investigate for the military. As the only survivor, Aris is quarantined and tested. Meanwhile, the contents of the Caribbean Lady’s cargo hold are frozen and examined, a scientist informing Stella that ‘This [one of the eggs] isn’t a plant. It’s an intensive culture of unknown bacteria. Maybe pathogenic, but definitely lethal [….] When the temperature rises, its cells mutate and it becomes lethal’. Stella deduces that the eggs, which the ship’s manifest suggests were headed for a warehouse in the Bronx, were intended to be used in a terrorist attack on New York City: the eggs, she claims, would have been planted in the city’s sewers until they ripened. Stella orders a raid on the warehouse in the Bronx and, inside, discovers hundreds more of the eggs – and men protecting them who seem to be under some form of mind-control. Rather than surrender, the men guarding the warehouse gather near the eggs and shoot one of them, causing the contents of the egg to spray over the men – resulting in their immediate deaths. Colonel Stella Holmes (Louise Marleau) is called in to investigate for the military. As the only survivor, Aris is quarantined and tested. Meanwhile, the contents of the Caribbean Lady’s cargo hold are frozen and examined, a scientist informing Stella that ‘This [one of the eggs] isn’t a plant. It’s an intensive culture of unknown bacteria. Maybe pathogenic, but definitely lethal [….] When the temperature rises, its cells mutate and it becomes lethal’. Stella deduces that the eggs, which the ship’s manifest suggests were headed for a warehouse in the Bronx, were intended to be used in a terrorist attack on New York City: the eggs, she claims, would have been planted in the city’s sewers until they ripened. Stella orders a raid on the warehouse in the Bronx and, inside, discovers hundreds more of the eggs – and men protecting them who seem to be under some form of mind-control. Rather than surrender, the men guarding the warehouse gather near the eggs and shoot one of them, causing the contents of the egg to spray over the men – resulting in their immediate deaths.

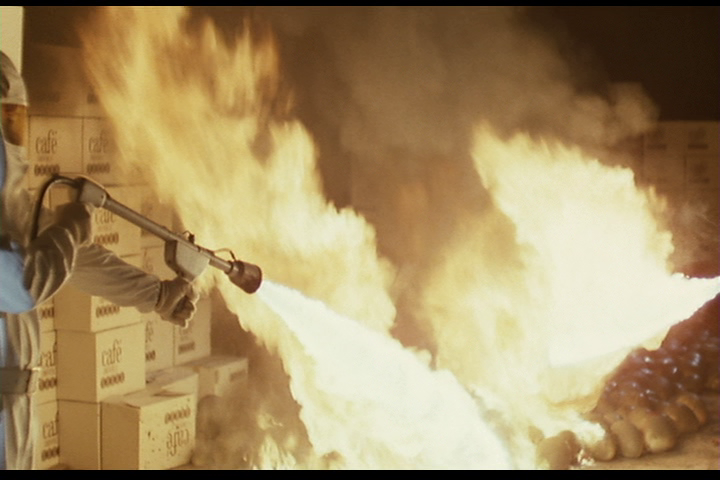

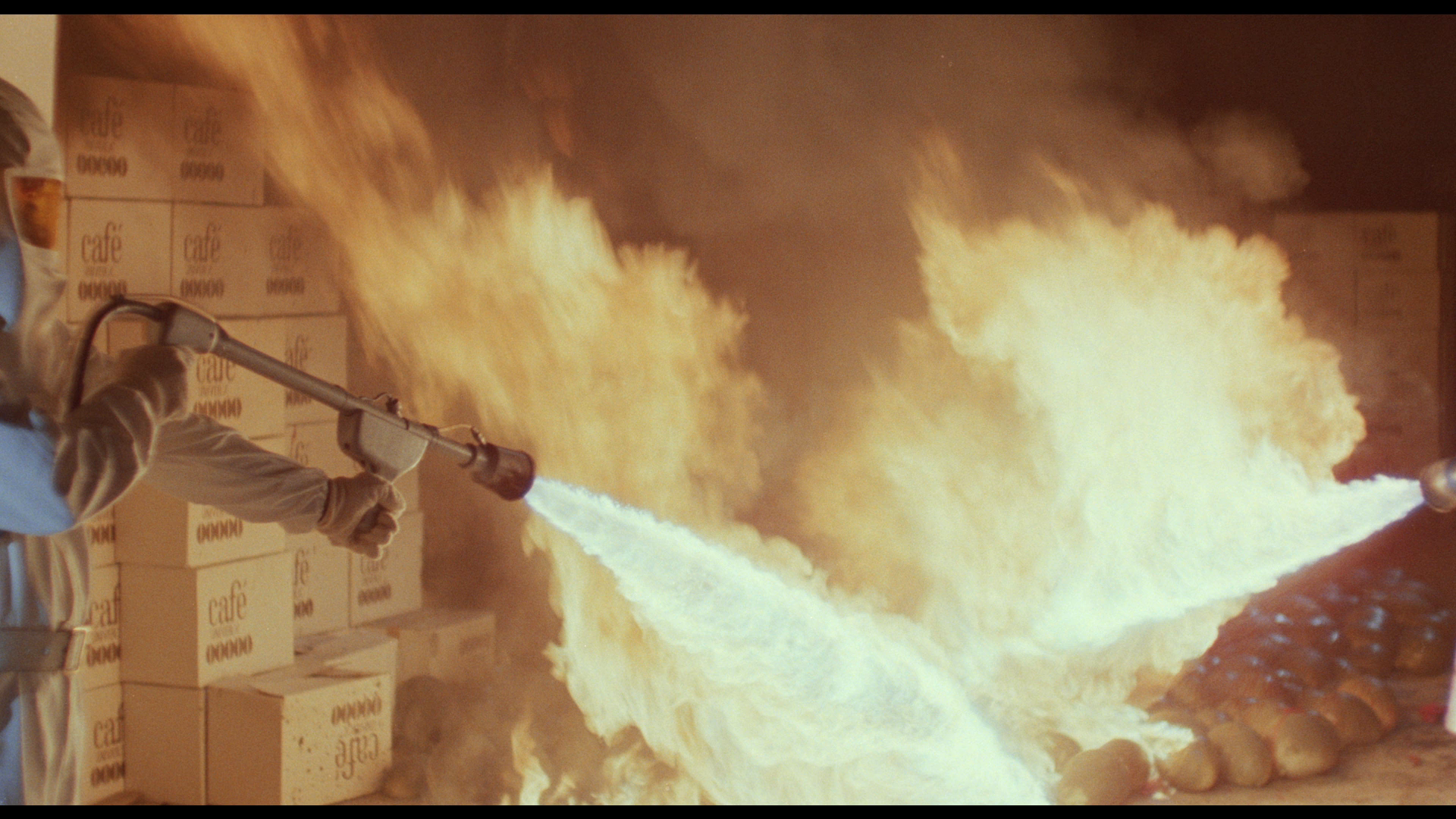

Stella orders the eggs in the warehouse to be destroyed with flamethrowers. (‘First you freeze all the ship’s cargo. Now you’re burning these. You don’t believe in half-measures’, Aris tells Stella.) Following the lead of a scientist, Dr Hilton (Mike Morris), who suggests that the eggs may have come from space, Stella reaches the conclusion that they were brought to Earth following a mission to Mars. The mission was manned by Commander Ian Hubbard (Ian McCulloch) and Hamilton (Siegfried Rauch). Upon returning to Earth, Hubbard told a fantastical story about landing on one of Mars’ polar ice caps and discovering a ‘damp and strangely humid’ cave filled with eggs and a terrifying creature. His story was, however, pooh-poohed by Hamilton, and Hubbard was forced out of his career. Stella, who was on the panel that dismissed Hubbard’s story as the product of an imbalanced mind, seeks out Hubbard, discovering that he is now a pitiful drunk.  Given seventy-two hours to solve the case, Stella enlists Aris and Hubbard as her helpers and travels to Colombia, to the headquarters of the UniverX coffee company. There, they discover that the head of the company is Hamilton, and his second in command is Perla de la Cruz (Gisela Hahn). Aware that Stella is a threat to his conspiracy, Hamilton plots to have her killed by, whilst Stella is in the shower, having one of the eggs planted in the bathroom of her hotel room and the door locked from the outside. However, she is saved by Aris and Hubbard. Given seventy-two hours to solve the case, Stella enlists Aris and Hubbard as her helpers and travels to Colombia, to the headquarters of the UniverX coffee company. There, they discover that the head of the company is Hamilton, and his second in command is Perla de la Cruz (Gisela Hahn). Aware that Stella is a threat to his conspiracy, Hamilton plots to have her killed by, whilst Stella is in the shower, having one of the eggs planted in the bathroom of her hotel room and the door locked from the outside. However, she is saved by Aris and Hubbard.

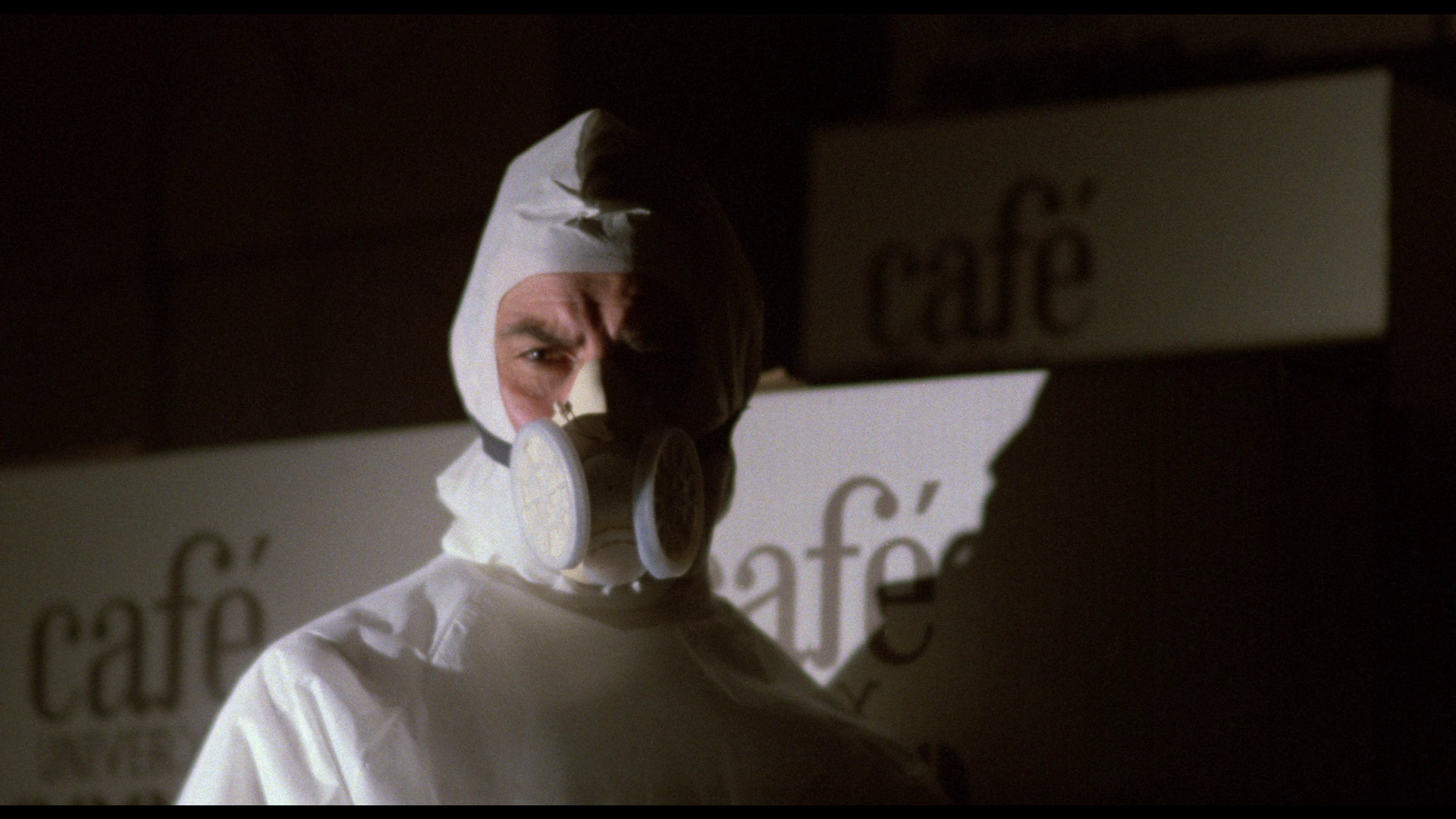

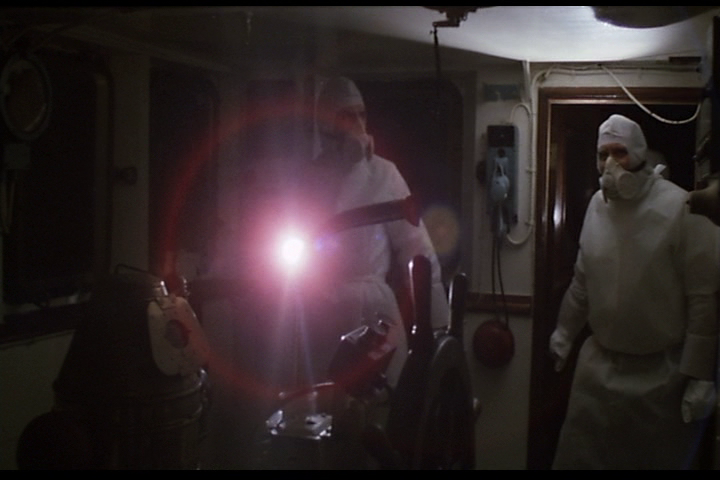

Deciding to ignore the attempt on Stella’s life, Stella and Aris arrive at the headquarters of UniverX, where they are greeted by Perla de la Cruz. De la Cruz offers to take them on a guided tour of the coffee factory. However, Stella and Aris are taken captive by armed men. Meanwhile, Hubbard has taken to the skies in a light aircraft. Unbeknownst to Hubbard, the plane has been sabotaged and crash lands in the brush. Hubbard explores the area and finds a location in which it appears that the eggs are ‘farmed’ and harvested by men in white haz-mat suits. Hubbard attacks one of these men and, disguising himself in his haz-mat suit, infiltrates UniverX’s headquarters. At the same time, Stella and Aris are taken by Hamilton to face a creature known only as ‘the Cyclops’: the alien queen and the source of the eggs.  The exact nature of the alien conspiracy is unclear, though when captured by Hamilton’s men and faced with the Cyclops, Stella questions, ’What’s the purpose of all this, Hamilton? It’s absolute madness’. ‘What’s the purpose of any living being?’, Hamilton asks in response, ‘To grow, multiply, survive. Eat so as not to be eaten; kill so as not to be killed. The strongest creature will crush the weakest’. Certainly, as Stella deduces at the start of the film, the plot to plant the eggs in New York’s sewer system is essentially a terrorist plot of sorts, committed by an army of ‘mind-controlled’ fanatics who, as the encounter in the Bronx warehouse suggests, are willing to sacrifice themselves in order to achieve their (or rather, their leader’s) goal. As such, it probably has its roots in the anxieties over terrorism that informed a large number of Italian films, especially many poliziesco pictures, during the anni di piombo (‘years of lead’) between 1968 and 1982 – over a decade of terrorist activity, committed by both the extreme left and the extreme right of the political spectrum, from the bombing of the Piazza Fontana in 1969 to the bombing of the Central Station of Bologna in 1980. Reflecting on the plot to plant the eggs in the sewers, Stella realises that the intention is that they detonate and cause havoc. ‘Sewers are damp, warm and snug’, she reasons, ‘just like a massive incubator. Imagine a hundred of these eggs scattered around New York’s sewers. They’d blow up the city in a few hours’. The damage that the eggs can cause is confirmed for the audience in the sequences depicting, in loving slow-motion, the evisceration of those who are near the eggs when they detonate – and reinforced in a sequence in which a scientist demonstrates for Stella the effect of the eggs by injecting fluid from one of them into a lab rat, causing the creature to explode from within. Stella’s prophecy comes true at the end of the film: we see the streets of New York City, the eggs concealed within the bags of rubbish that line the pavements. The eggs begin to pulsate and explode. This closing sequence recalls the closing sequence of Zombi 2, in which Peter West (Ian McCulloch) and Anne Bowles (Tisa Farrow) escape the zombie-infested Caribbean island of Matul and hope to return home to New York City, but Fulci cuts away to a high-angle shot of the Brooklyn Bridge that shows zombies shambling across it whilst, on the audio track, a desperate radio broadcast warns the station’s listeners of the presence of the undead. The exact nature of the alien conspiracy is unclear, though when captured by Hamilton’s men and faced with the Cyclops, Stella questions, ’What’s the purpose of all this, Hamilton? It’s absolute madness’. ‘What’s the purpose of any living being?’, Hamilton asks in response, ‘To grow, multiply, survive. Eat so as not to be eaten; kill so as not to be killed. The strongest creature will crush the weakest’. Certainly, as Stella deduces at the start of the film, the plot to plant the eggs in New York’s sewer system is essentially a terrorist plot of sorts, committed by an army of ‘mind-controlled’ fanatics who, as the encounter in the Bronx warehouse suggests, are willing to sacrifice themselves in order to achieve their (or rather, their leader’s) goal. As such, it probably has its roots in the anxieties over terrorism that informed a large number of Italian films, especially many poliziesco pictures, during the anni di piombo (‘years of lead’) between 1968 and 1982 – over a decade of terrorist activity, committed by both the extreme left and the extreme right of the political spectrum, from the bombing of the Piazza Fontana in 1969 to the bombing of the Central Station of Bologna in 1980. Reflecting on the plot to plant the eggs in the sewers, Stella realises that the intention is that they detonate and cause havoc. ‘Sewers are damp, warm and snug’, she reasons, ‘just like a massive incubator. Imagine a hundred of these eggs scattered around New York’s sewers. They’d blow up the city in a few hours’. The damage that the eggs can cause is confirmed for the audience in the sequences depicting, in loving slow-motion, the evisceration of those who are near the eggs when they detonate – and reinforced in a sequence in which a scientist demonstrates for Stella the effect of the eggs by injecting fluid from one of them into a lab rat, causing the creature to explode from within. Stella’s prophecy comes true at the end of the film: we see the streets of New York City, the eggs concealed within the bags of rubbish that line the pavements. The eggs begin to pulsate and explode. This closing sequence recalls the closing sequence of Zombi 2, in which Peter West (Ian McCulloch) and Anne Bowles (Tisa Farrow) escape the zombie-infested Caribbean island of Matul and hope to return home to New York City, but Fulci cuts away to a high-angle shot of the Brooklyn Bridge that shows zombies shambling across it whilst, on the audio track, a desperate radio broadcast warns the station’s listeners of the presence of the undead.

Contamination’s opening sequence also obviously draws on the similar opening sequence of Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2. In Fulci’s film, a seemingly abandoned yacht drifts into New York’s harbour and is intercepted by the harbour patrol. Boarding the yacht, two harbour patrol officers find themselves attacked by a zombie. Contamination replays this sequence but on a larger scale: in this film, the boat that drifts into Manhattan harbour is a large container ship, the Caribbean Lady. The film opens on a police helicopter circling over Manhattan. The helicopter receives a radio call: the Caribbean Lady is on a collision course and cannot be reached by radio. The ship is intercepted and towed into an empty dock, where it is boarded by Lieutenant Aris, Dr Turner and several other policemen. Aris, who has already conducted a preliminary investigation of the ship, tells Turner that ‘There wasn’t a soul on board, just this weird smell, like something rotting’. Investigating the ship’s cabins, they find the eviscerated and putrefying body of the ship’s captain. ‘It’s almost as if… I don’t know, it’s almost as if he exploded’, Turner observes. ‘Exploded?’, Aris questions unbelievingly. ‘Yeah, but not because of a bomb. It’s more like he exploded from the inside [….] It’s as if some force inside him was unleashed’. The investigation of the Caribbean Lady clearly has parallels with the crew of the Nostromo’s fateful examination of the crashed alien spacecraft in Alien. However, in their depiction of abandoned ships that are found to be carrying ‘plagues’ of sorts (in Zombi 2, the zombies; in Contamination, the alien eggs), the opening sequences of both Zombi 2 and Contamination also draw on the Demeter in Bram Stoker’s Dracula: the Russian schooner which Dracula uses as transport to Whitby, feasting on the ship’s crew members during the journey, leaving the apparently abandoned ship to run aground in Whitby harbour. Like the ships in Zombi 2 and Contamination, the Demeter carries a supernatural ‘plague’, the vampire – something made more overt in both versions of Nosferatu (F W Murnau, 1922; Werner Herzog, 1979), in which the Demeter carries rats which are linked to the bubonic plague. Contamination’s opening sequence also obviously draws on the similar opening sequence of Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2. In Fulci’s film, a seemingly abandoned yacht drifts into New York’s harbour and is intercepted by the harbour patrol. Boarding the yacht, two harbour patrol officers find themselves attacked by a zombie. Contamination replays this sequence but on a larger scale: in this film, the boat that drifts into Manhattan harbour is a large container ship, the Caribbean Lady. The film opens on a police helicopter circling over Manhattan. The helicopter receives a radio call: the Caribbean Lady is on a collision course and cannot be reached by radio. The ship is intercepted and towed into an empty dock, where it is boarded by Lieutenant Aris, Dr Turner and several other policemen. Aris, who has already conducted a preliminary investigation of the ship, tells Turner that ‘There wasn’t a soul on board, just this weird smell, like something rotting’. Investigating the ship’s cabins, they find the eviscerated and putrefying body of the ship’s captain. ‘It’s almost as if… I don’t know, it’s almost as if he exploded’, Turner observes. ‘Exploded?’, Aris questions unbelievingly. ‘Yeah, but not because of a bomb. It’s more like he exploded from the inside [….] It’s as if some force inside him was unleashed’. The investigation of the Caribbean Lady clearly has parallels with the crew of the Nostromo’s fateful examination of the crashed alien spacecraft in Alien. However, in their depiction of abandoned ships that are found to be carrying ‘plagues’ of sorts (in Zombi 2, the zombies; in Contamination, the alien eggs), the opening sequences of both Zombi 2 and Contamination also draw on the Demeter in Bram Stoker’s Dracula: the Russian schooner which Dracula uses as transport to Whitby, feasting on the ship’s crew members during the journey, leaving the apparently abandoned ship to run aground in Whitby harbour. Like the ships in Zombi 2 and Contamination, the Demeter carries a supernatural ‘plague’, the vampire – something made more overt in both versions of Nosferatu (F W Murnau, 1922; Werner Herzog, 1979), in which the Demeter carries rats which are linked to the bubonic plague.

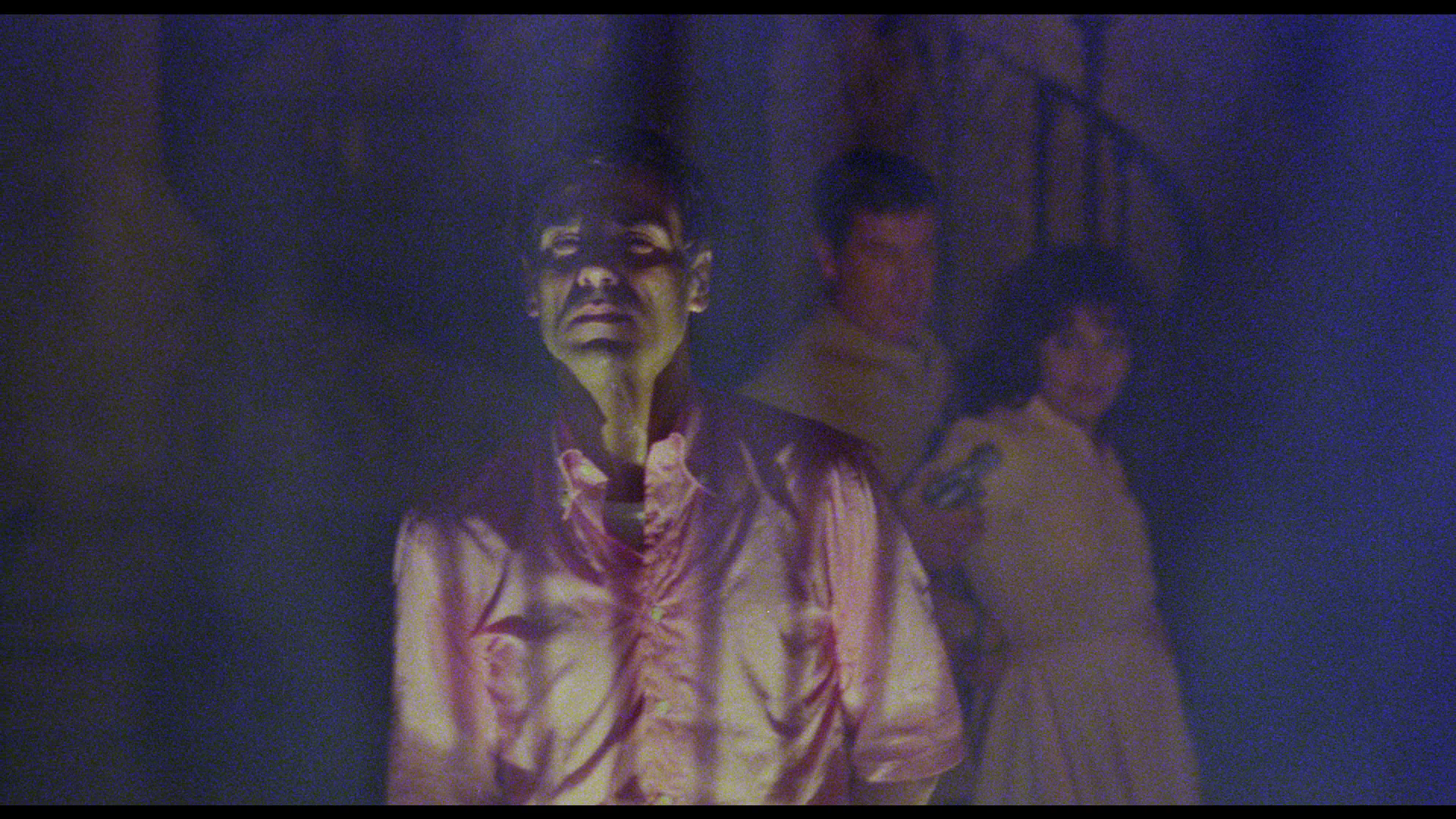

Earlier, I mentioned one of the filoni that didn’t necessarily translate so well to non-Italian audiences: the commedia sexy all’italiana. One of the key elements of the commedia sexy pictures of this period was the mocking of the masculinity of the films’ male characters (much as a major source of humour within the thematically similar, and roughly contemporaneous, Carry On films was a parodic depiction of masculinity). The films often contained depictions of the inetto: an ‘inept’ man out of step with changing society, often represented as a fool who is the subject of the mockery of others, his masculinity questioned. The inetto has his origins in the commedia dell’arte but was also often the subject of Fellini’s films (for example, Marcello Mastroianni’s characters, Marcello Rubini and Guido Anselmi, in La dolce vita, 1960, and 8½, 1963). Contamination obviously draws on Alien’s iconography, in terms of its use of ‘the monster and the egg’ and the chest-bursting imagery of Scott’s film; but it also borrows Alien’s focus on a strong female protagonist. In the case of Contamination, this character is Colonel Stella Holmes, played by the Canadian actress Louise Marleau. The film’s depiction of a mature, authoritative woman is complimented by Contamination’s two male leads, who are both to some extent versions of the inetto. On their first meeting, whilst being tested after his experiences on the Caribbean Lady, Aris churlishly addresses Stella as ‘sweetheart’. ‘Please don’t call me “sweetheart”, young man [….] I’m a colonel, Security Service, directly responsible to the Pentagon. Special Division Five’, Stella informs Aris.  Similarly, when we first see Hubbard, roughly half an hour into the film, he is a man who has been destroyed by the lack of belief in his story about the cave filled with strange eggs that he witnessed on Mars, his masculine agency undermined by his dismissal from the space programme (a dismissal in which Stella apparently played a strong role). Hubbard is now a drunk, disengaged from and out of step with the world around him: the first shot of him within the film sees the camera behind him as he slouches in an armchair in his apartment, gazing passively out of a window. He is surrounded by beer cans, one of the cans held in his right hand which is draped over the armrest of the chair on which he sits; and as he becomes aware of Stella’s presence on the other side of the door to his home, Hubbard allows the can to fall to the floor. Answering the door to Stella, a bitter Hubbard asserts, ‘I was kicked out [of the space programme] like some crazy visionary [….] Come on, colonel. What do you want to know? How many times a week I screw?’ ‘If you’re always like this’, Stella responds, referring to Hubbard’s drunken state and his association of his masculine agency with his sexual prowess, ‘you couldn’t get it up using a crane’. Similarly, when we first see Hubbard, roughly half an hour into the film, he is a man who has been destroyed by the lack of belief in his story about the cave filled with strange eggs that he witnessed on Mars, his masculine agency undermined by his dismissal from the space programme (a dismissal in which Stella apparently played a strong role). Hubbard is now a drunk, disengaged from and out of step with the world around him: the first shot of him within the film sees the camera behind him as he slouches in an armchair in his apartment, gazing passively out of a window. He is surrounded by beer cans, one of the cans held in his right hand which is draped over the armrest of the chair on which he sits; and as he becomes aware of Stella’s presence on the other side of the door to his home, Hubbard allows the can to fall to the floor. Answering the door to Stella, a bitter Hubbard asserts, ‘I was kicked out [of the space programme] like some crazy visionary [….] Come on, colonel. What do you want to know? How many times a week I screw?’ ‘If you’re always like this’, Stella responds, referring to Hubbard’s drunken state and his association of his masculine agency with his sexual prowess, ‘you couldn’t get it up using a crane’.

Having realised her previous mistake in believing Hamilton, Stella offers to try to make amends to Hubbard, promising that she can reinstate him at his previous grade. In response, Hubbard angrily reminds her of his pathetic, fallen state, ‘I don’t give a damn about your grades. What good will they do me? With all my diplomas and merits, I’m still a wreck’. ‘I thought that under that wreck there was still a man’, Stella suggests, ‘A man who had the guts to go to Mars; a man who fought to the end for what he believed was right; a man who could help us save this damn planet from a fate worse than death. But that man remained up there on the glaciers of Mars’. ‘If you were a man, I’d…’, Hubbard begins to threaten Stella. ‘What would you do?’, she asks before suggesting, ‘Nothing. You wouldn’t do anything. You’re no longer capable of doing anything. You’re a wimp: you’re only half a man’. In response to this taunting, Hubbard strikes Stella, telling her, ‘That’s just so you realise it’s best not to mess with me’. ‘Very well’, Stella smirks, her verbal challenge to Hubbard’s masculinity apparently calculated to result in shocking Hubbard out of his passivity and his inetto-like state, ‘That’s just how I like you, Hubbard’.  When the trio arrive in Colombia, Aris and Hubbard say good evening to Stella as she retires to her room for a shower. Away from her company, Aris reflects on his inability to seduce Stella: ‘What a shame. Such a beautiful woman’, he observes, ‘Is something wrong with her, or is she happily married?’ ‘Of course’, Hubbard tells him, ‘To a whip and a test tube. You know, I think the colonel would have been in her element in one of those ice caves on Mars’. ‘Deep down all women are the same’, Aris philosophises chauvinistically, ‘It’s just a question of knowing how to handle them’. A comical sequence (which could almost come from a commedia sexy film of the era) follows in which Aris clearly intends to return to Stella’s room and knock on her door in the hope of conversing with her privately (and possibly seducing her), but Hubbard insists on interrupting him, an embarrassed Aris retreating to his own room. Later in the film, after they have both been taken captive by Hamilton, Aris seduces Stella by telling her, ‘You’ve always made me feel like a caveman. You’re the first woman in my whole life I didn’t have the guts to try it on with’. Stella responds by kissing him, the bond between the authoritative woman and the inetto sealed – which makes what happens at the climax of the film, a shocking moment by the standards of popular cinema, all the more tragic. When the trio arrive in Colombia, Aris and Hubbard say good evening to Stella as she retires to her room for a shower. Away from her company, Aris reflects on his inability to seduce Stella: ‘What a shame. Such a beautiful woman’, he observes, ‘Is something wrong with her, or is she happily married?’ ‘Of course’, Hubbard tells him, ‘To a whip and a test tube. You know, I think the colonel would have been in her element in one of those ice caves on Mars’. ‘Deep down all women are the same’, Aris philosophises chauvinistically, ‘It’s just a question of knowing how to handle them’. A comical sequence (which could almost come from a commedia sexy film of the era) follows in which Aris clearly intends to return to Stella’s room and knock on her door in the hope of conversing with her privately (and possibly seducing her), but Hubbard insists on interrupting him, an embarrassed Aris retreating to his own room. Later in the film, after they have both been taken captive by Hamilton, Aris seduces Stella by telling her, ‘You’ve always made me feel like a caveman. You’re the first woman in my whole life I didn’t have the guts to try it on with’. Stella responds by kissing him, the bond between the authoritative woman and the inetto sealed – which makes what happens at the climax of the film, a shocking moment by the standards of popular cinema, all the more tragic.

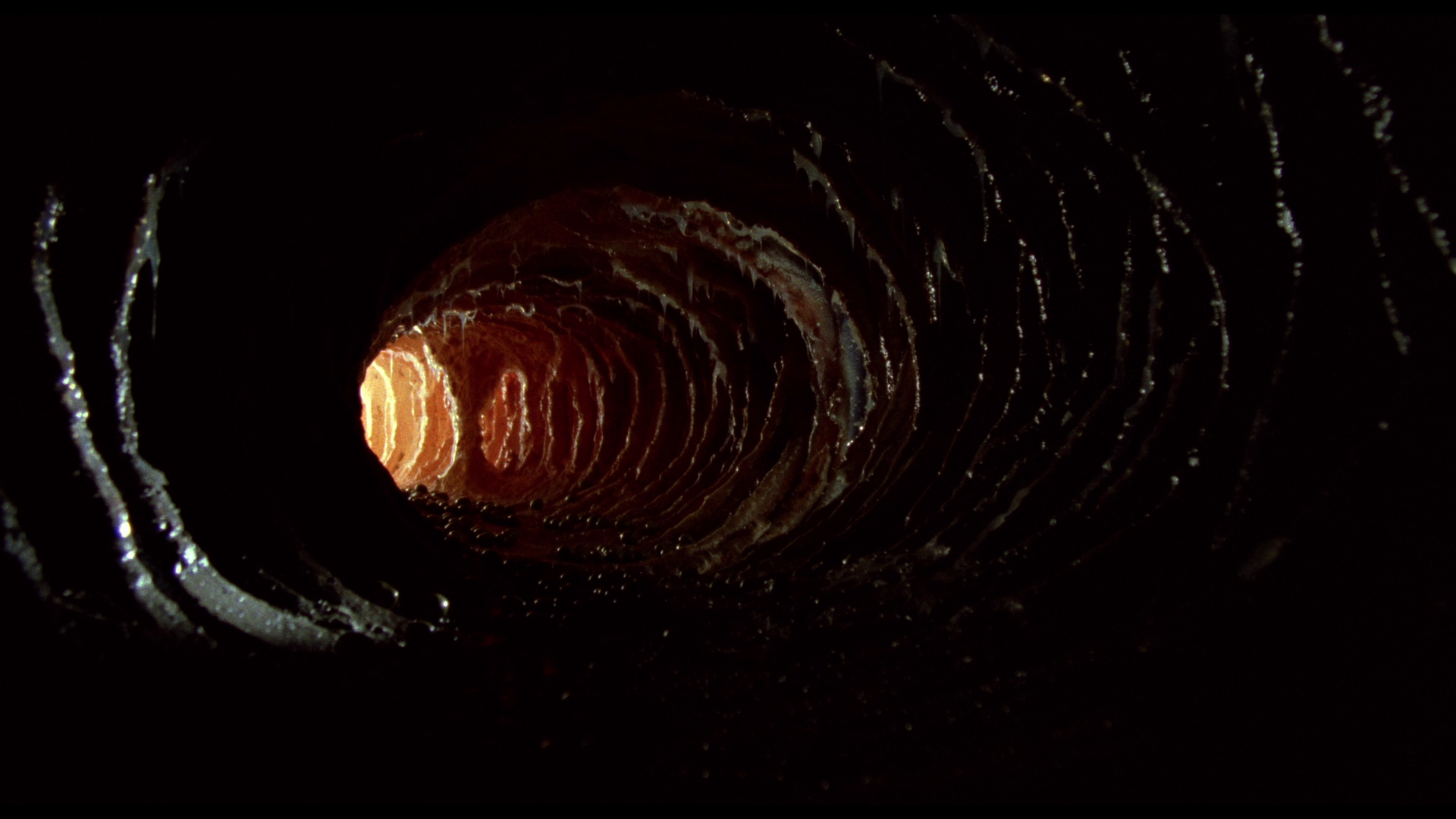

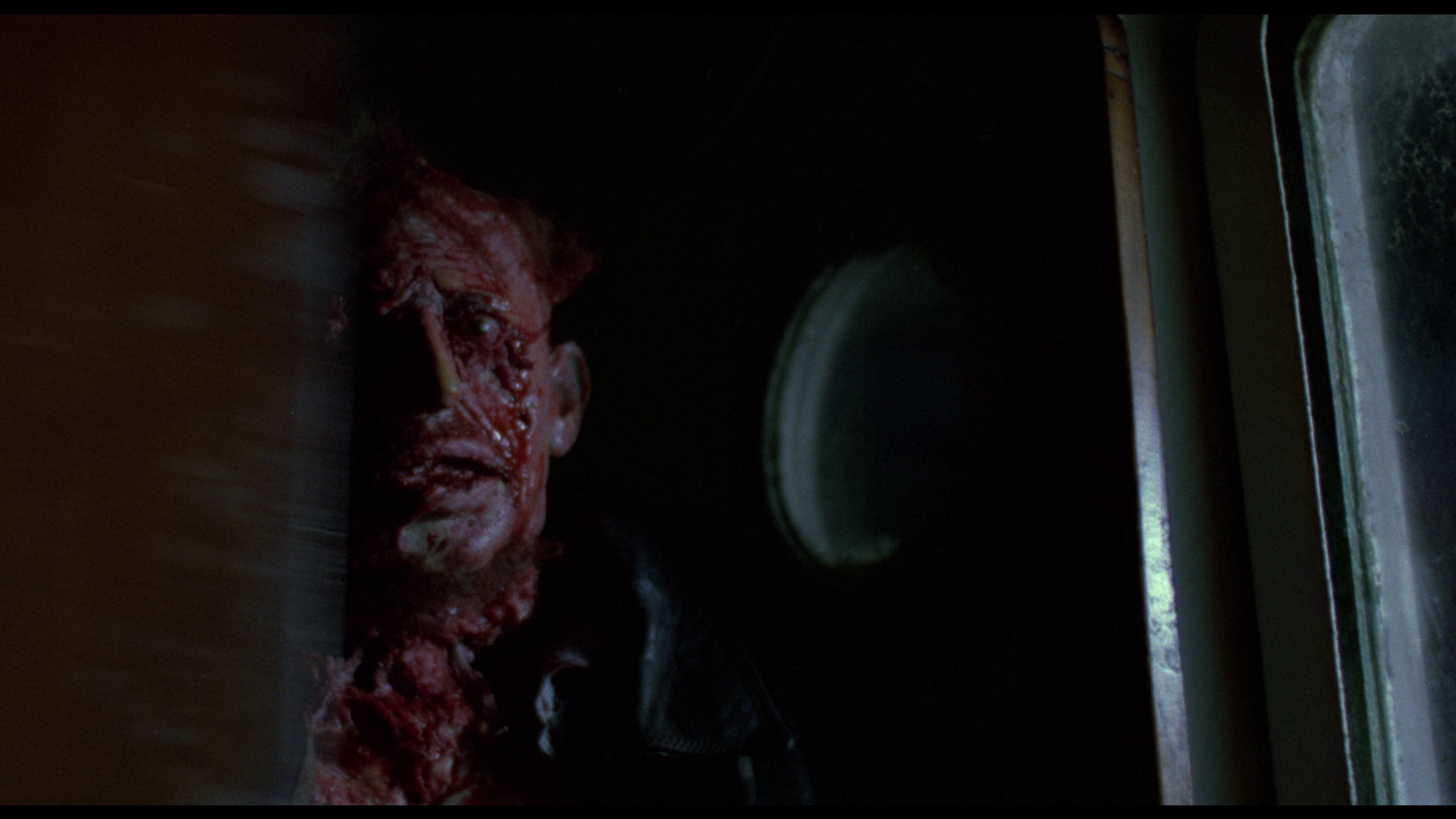

As if to underscore the film’s depiction of Stella as a mature, confident and authoritative woman (and, in terms of her dominance of the narrative, clearly the film’s protagonist, despite the competition in that regard from both Aris and Hubbard), the Cyclops at the end of the film is also coded as female: an alien queen complete with a chute for laying her eggs. Strangely, this aspect of the film, and the confrontation between the protagonists and the alien queen in her chamber, bears striking similarities with James Cameron’s sequel to Alien, Aliens (1986). Additional similarities with Cameron’s film include the use of a flamethrower to burn the alien eggs, and the sequence in which Hamilton has his goons lock Stella in her bathroom with an alien egg looks to Hitchcock’s Psycho for its inspiration but also finds its corollary in the later Aliens in the sequence in which ‘company man’ Carter Burke (Paul Reiser) locks Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and Newt (Carrie Henn) in a lab with a ‘facehugger’, intending them to be impregnated by the creature. Contamination was originally released in the UK on videotape by ViP prior to the Video Recordings Act. During the ‘Video Nasties’ moral panic, in 1983 the film ended up on the Director of Public Prosecution’s list of films that were likely to be found obscene, but it was removed from the list within a fairly short space of time. After the VRA, Contamination was released in a cut form by European Creative Films. Almost three minutes of cuts were made to the discovery of the eviscerated corpses aboard the Caribbean Lady, the ‘chest-bursting’ sequences, and the sequence in which the Cyclops eats a man’s head. The film was finally passed uncut for the Anchor Bay UK DVD release in 2004. This Blu-ray release from Arrow is completely uncut and runs for 95:20 mins.

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, Contamination takes up approximately 27Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.  As can be seen from the screengrabs below, Arrow’s Blu-ray offers a huge improvement over the Blue Underground DVD, the benchmark for DVD releases of Contamination. Arrow’s presentation opens up the compositions slightly, offering a little more information on both the left and right-hand sides of the frame. The new 2k restoration from the film’s negative offers detail that is a substantial improvement over the previous DVD releases, with an impressive level of fine detail on display (eg, the beads of sweat in the tight close-up of Aris’ eyes). Contrast levels look slightly ‘off’ during the optically-printed titles sequence (naturally) but quickly settle down after that and are uniformly good throughout the rest of the film, with rich, deep blacks during the nighttime sequences and some beautifully moody chiaroscuro lighting at the climax (something which wasn’t presented particularly well on the film’s previous DVD releases). The presentation is remarkably free of debris and any form of noticeable damage, and a characteristically strong encode handles the grain structure well, resulting in a presentation that has the look and texture of 35mm film – or as near as a current digital simulacrum will allow. As can be seen from the screengrabs below, Arrow’s Blu-ray offers a huge improvement over the Blue Underground DVD, the benchmark for DVD releases of Contamination. Arrow’s presentation opens up the compositions slightly, offering a little more information on both the left and right-hand sides of the frame. The new 2k restoration from the film’s negative offers detail that is a substantial improvement over the previous DVD releases, with an impressive level of fine detail on display (eg, the beads of sweat in the tight close-up of Aris’ eyes). Contrast levels look slightly ‘off’ during the optically-printed titles sequence (naturally) but quickly settle down after that and are uniformly good throughout the rest of the film, with rich, deep blacks during the nighttime sequences and some beautifully moody chiaroscuro lighting at the climax (something which wasn’t presented particularly well on the film’s previous DVD releases). The presentation is remarkably free of debris and any form of noticeable damage, and a characteristically strong encode handles the grain structure well, resulting in a presentation that has the look and texture of 35mm film – or as near as a current digital simulacrum will allow.

Some screen grabs offering a comparison of this new HD presentation with the DVD released by Blue Underground in 2003 are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The viewer may choose between the film’s English audio or the Italian audio – both presented in LPCM 1.0 mono. Though the English track features the voices of many of the film’s principal actors (including McCulloch and Marleau), both audio tracks were post-synched and so neither is more ‘legitimate’ than the other. Optional English HoH subtitles are provided for the English track, and optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue are provided for the Italian track. There are some subtle differences between the two: the Italian track seems a little more ‘busy’, with some moments of silence filled with radio chatter, etc, in comparison with the English track. Although no doubt many viewers will default to the English track, owing to it containing McCulloch’s own voice, Arrow’s inclusion of the Italian track (with accompanying English subtitles) is something to be thankful for: it’s a viable alternative, and arguably owing to the less clumsy dubbing of the ancillary characters (in relation to the English track), is a more convincingly atmospheric track overall. Both audio tracks are clean and clear with good range. The English track seems to have a little more ‘punch’ in the bass, as can be heard in sequences featuring Goblin’s score for the film, but there’s little difference between the two.

Extras

The disc includes a very good array of contextual material:  - an audio commentary by Chris Alexander. Here, the editor of Fangoria enthusiastically reflects on his relationship with the film and his love of Italian genre cinema of this period more generally. It’s a lively, informal track. - an audio commentary by Chris Alexander. Here, the editor of Fangoria enthusiastically reflects on his relationship with the film and his love of Italian genre cinema of this period more generally. It’s a lively, informal track.

- ‘Luigi Cozzi on Contamination’ (22:55). This archival featurette (in Italian, with optional English subtitles), entitled ‘Notes on Science-Fiction Cinema’, opens with Luigi Cozzi, in a gas mask and monster glove, working at a typewriter – before removing the get-up and referring to it as ‘inspirational ambience’. In a relaxed setting (his office), Cozzi discusses the position of science-fiction films within Italian cinema generally, before moving on to discussing Contamination, asserting that though the film was influenced by Alien ‘I didn’t want to copy Alien, and it’s not my style to copy other movies, but I was determined to have these two elements [the alien egg and the monster]’. We are presented with behind-the-scenes footage of the production of Contamination, showing Cozzi and his cast and crew at work (and with intermittent narration by Cozzi), before returning to Cozzi’s office, where he discusses the effect of the pulsating alien egg and demonstrates how it was achieved. - ‘Contamination Q&A’ (41:05). Cozzi and one of the film’s stars, Ian McCulloch, field questions from the audience at a 2014 screening of Contamination. - ‘Sound of the Cyclops (11:30). In this newly-produced featurette, Maurizio Guarini discusses (in English) his work as a keyboardist with the prog rock band Goblin, who provided the score for Contamination. Guarini talks about Goblin and the group’s association with horror films, and he suggests that his memories of Contamination specifically aren’t very ‘focused’ – that the score developed alongside the scores Goblin produced for Patrick (Richard Franklin, 1978) and Joe D’Amato’s Buio Omega (Blue Holocaust/Beyond the Darkness, 1979). - ‘Luigi Cozzi vs Lewis Coates’ (42:52). This lengthy interview with Cozzi features the writer-director talking directly to the camera (in Italian, with optional English subtitles) whilst images from his films are superimposed in the background. Cozzi reflects on his love for science-fiction, his early years making films at home with a Kodak 8mm camera, and his work during the late 1960s writing for science-fiction magazines. He talks about his relationship with Argento and his admiration for L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1969); Cozzi asserts that when he saw Argento’s directorial debut he ‘felt it was the start of a new era of filmmaking’. The piece ends with a preview of Cozzi’s no-budget picture Blood on Méliès’ Moon. - ‘Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery’ (17:25). Here, in this newly-produced featurette, Maitland McDonagh and Chris Poggiali – interviewed separately – discuss the filone principle and explore the ways in which Italian cinema was shaped by the successes of Jaws, Star Wars and Mad Max 2 (George Miller, 1981). McDonagh and Poggiali reflect on some of the films inspired by these American models, and Poggiali discusses some of the legal problems surrounding the US release of Enzo Castellari’s L’ultimo squalo (The Last Shark/Great White, 1981), which Universal felt too closely imitated Jaws. McDonagh suggests that there were ‘a lot of Star Wars knock-offs which had none of what Star Wars had which made people like Star Wars’, and the pair talk at length about the Italian post-nuclear films which followed in the wake of Miller’s Mad Max 2 and John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981). (Interestingly, neither McDonagh or Poggiali seem to mention the impact that Walter Hill’s The Warriors, 1979, had on some of these films, in terms of its depiction of gangs and gang culture.) McDonagh suggests that the use of rundown locations in the South Bronx in films such as Castellari’s I guerrieri di Bronx (The Bronx Warriors, 1982) and Fuga dal Bronx (Escape from the Bronx/Bronx Warriors 2, 1983) have the films ‘the best special effects and set design that no money had to buy’. McDonagh also asserts that these films essentially play out like Westerns, as ‘they’re all ultimately about the war between civilization and the wilderness’. They also had two audiences: ‘they played to people in the States, who recognised echoes of urban unrest [….] and then they played to people who thought that cities were all Sodom and Gomorrah on the nearest river’. - Graphic Novel (0:54). This is the same adaptation of Contamination into graphic novel form that appeared on the 2003 DVD release by Anchor Bay. - The film's trailer (3:14).

Packaging

The film is presented in an Amaray case with reversible artwork. Included within retail copies will be a booklet with an enthusiastic new piece of writing about Contamination by Chris Alexander and illustrated with stills and promotional artwork from the film itself.

Overall

I will quite happily admit to being a big fan of Contamination, first encountering it via the European Creative Films VHS release from the mid-1980s. Like many Italian exploitation films, it’s something of an acquired taste, but it has a sense of energy and almost Nigel Kneale-esque paranoia that weaves its own unique spell – despite the ostensibly derivative plot. There’s a subtle willingness within the film to buck trends (Cozzi is unafraid to present the rather shocking death of a main character at the film’s climax) and some odd similarities with James Cameron’s official sequel to Alien. (My young son also has an alien Cyclops toy which seems bizarrely similar to the alien queen in this film, so perhaps the film has more fans than one might imagine.) Despite its roots in American films, Contamination also displays a uniquely Italian flavour: its depiction of violence and its focus on the alien eggs-as-terrorist plot connects it with many of the other Italian films made during the anni di piombo, and the film’s co-option of the strong female protagonist of Ridley Scott’s Alien results in a picture that offers a representation of gender politics that has some similarities with the commedia sexy all’italiana films of the era – especially the focus on the inetto, or ‘inept man’. I will quite happily admit to being a big fan of Contamination, first encountering it via the European Creative Films VHS release from the mid-1980s. Like many Italian exploitation films, it’s something of an acquired taste, but it has a sense of energy and almost Nigel Kneale-esque paranoia that weaves its own unique spell – despite the ostensibly derivative plot. There’s a subtle willingness within the film to buck trends (Cozzi is unafraid to present the rather shocking death of a main character at the film’s climax) and some odd similarities with James Cameron’s official sequel to Alien. (My young son also has an alien Cyclops toy which seems bizarrely similar to the alien queen in this film, so perhaps the film has more fans than one might imagine.) Despite its roots in American films, Contamination also displays a uniquely Italian flavour: its depiction of violence and its focus on the alien eggs-as-terrorist plot connects it with many of the other Italian films made during the anni di piombo, and the film’s co-option of the strong female protagonist of Ridley Scott’s Alien results in a picture that offers a representation of gender politics that has some similarities with the commedia sexy all’italiana films of the era – especially the focus on the inetto, or ‘inept man’.

For fans of Italian exploitation cinema, Contamination is a hugely entertaining film which weaves a web of similarities with other Italian films (such as Fulci’s Zombi 2) as well as the American and British science-fiction films that it more obviously mimicks. The presentation of the film on Arrow’s Blu-ray is incredibly impressive, an enormous improvement over the DVDs that have been available, and contains a superb range of contextual material. References: Baschiera, Stefano & Di Chiara, Francesco, 2010: ‘A Postcard from the Grindhouse: Exotic Landscapes and Italian Holidays in Lucio Fulci’s Zombie and Sergio Martino’s Torso’. In: Weiner, Robert G & Cline, John (eds), 2010: Cinema Inferno: Celluloid Explosions from the Cultural Margins. Maryland: Scarecrow Press: 101-123 Fischer, Dennis, 2000: Science Fiction Film Directors, 1895-1998. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Nakahara, Tamao, 2013: ‘Moving Masculinity: Incest Narratives in Italian Sex Comedies’. In: Bayman, Louis & Rigoletto, Sergio (eds), 2013: Popular Italian Cinema. London: Palgrave-Macmillan: 98-116 Newman, Kim, 2011: Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. London: Bloomsbury Publishing (Revised Edition) Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

Blue Underground DVD:

Arrow BD:

More grabs from the Arrow BD:

|

|||||

|