|

|

Fuku-chan of FukuFuku Flats AKA Fukufukusou no Fukuchan

R0 - United Kingdom - Third Window Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats (Fujita Yosuke, 2014) Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats (Fujita Yosuke, 2014)

This film, the second of its director Fujita Yosuke, was financed by an international consortium. One of the production companies involved was Third Window Films, the excellent and well-loved UK distributor which is also responsible for this DVD release. The film follows Fujita’s first picture, Fine, Totally Fine (2008). In the six years between the production of Fine, Totally Fine and Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats, Fujita worked in theatre, wrote and directed a television film, Saba, and a segment of the portmanteau picture Quirky Guys and Gals (2011). The title of the latter film pretty much sums up Fujita’s main area of focus: the quirky lives of young men and women who, though either in their late twenties or early thirties, exhibit elements of childlike behaviour and struggle to face the challenges of adulthood or make connections with those around them. Parallels may be drawn between Fujita’s films and the Generation X ‘slacker comedies’ made in America during the 1990s (for example, Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, 1993; or Kevin Smith’s Clerks, 1994) – or perhaps the more recent films of the no-budget ‘mumblecore’ movement. ‘Slacker’-type films in Japan are often associated with pictures by directors such as Yamashita Nobuhiro (for example, Hazy Life, 1999, and Ramblers, 2003), whose films during the early 2000s dealt with the complex fallout from the recession in the 1990s (the ‘Lost Decade’) that ended the ‘bubble’ economy of the 1980s. In these pictures, young people are shown eking out an existence in which they are on the margins of society, working low-paid, part-time and temporary proletarian jobs – much as American ‘slacker’ pictures of the 1990s featured protagonists in similar professions (for example, Kevin Smith’s Clerks, 1994). In Japan, these types of people are often labeled freeters – the Japanese equivalent of a ‘slacker’. John Berra has said that the ‘ruptured economy of Japan has caused employment problems for those entering the employment market since the 1990s, leading to the widespread use of the term “freeter” to refer to part-time workers of [sic] job-hoppers who struggle to survive without a steady income or lack sufficient professional motivation due to the lack of some sense of career direction’ (Berra, 2012: 9). Freeters tend to be classified as between the ages of fifteen and thirty-five; Berra suggests that the term freeter can be seen as somewhat glamorous as it indicates ‘a young person who has the ability to […] earn a high-level income but shuns the salaryman lifestyle in favour of more personal pursuits and a rejection of capitalist ideology, thereby encouraging the image of a youthful alternative culture that is over-educated yet under-motivated’ (ibid.). Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats focuses on Fukuda (‘Fuku-Chan’, played by Ôshima Miyuki), a 32 year old who works with a team of painters and decorators that includes his friend Schimacchi (Arakawa Yoshiyoshi). Fukuda is an innocent soul, a born peacemaker who takes pleasure in designing and flying kites. Schimacchi and his girlfriend Yoshida (Kurokawa Mei) try to set the single Fukuda up with Yoshida’s friend Katsuko, but to no avail: whilst on a double date – a picnic – with Katsuko, Schimacchi and Yoshida, Fukuda would prefer to spend time flying his kites with his oddball freeter neighbours from Fukufuku Flats, the paranoid panty thief Nonoshita (Iida Asato), and the pet snake-owning Ivy League graduate Mabuchi (Tateto Serizawa).  Meanwhile, Chiho (Mizukawa Asami) wins a photography prize, awarded by the highly-respected and profoundly eccentric photographer Numakura, for one of her photographs. Chiho works for a large American firm but considers walking out of her lucrative job and following her dream of becoming a photographer. Numakura gives Chiho a gift of one of his specially-designed, rather phallic cameras, and promises to mentor her. However, during their first mentoring session Numakura submits Chiho to a deeply humiliating bout of sexual harassment. Following this, Chiho vows to abandon her dream of becoming a photographer. Without a job and downtrodden, she visits a restaurant where the owner, seeing that Chiho is in need of guidance, suggests that Chiho’s unhappiness is owing to her need to pay penance for a past sin. Meanwhile, Chiho (Mizukawa Asami) wins a photography prize, awarded by the highly-respected and profoundly eccentric photographer Numakura, for one of her photographs. Chiho works for a large American firm but considers walking out of her lucrative job and following her dream of becoming a photographer. Numakura gives Chiho a gift of one of his specially-designed, rather phallic cameras, and promises to mentor her. However, during their first mentoring session Numakura submits Chiho to a deeply humiliating bout of sexual harassment. Following this, Chiho vows to abandon her dream of becoming a photographer. Without a job and downtrodden, she visits a restaurant where the owner, seeing that Chiho is in need of guidance, suggests that Chiho’s unhappiness is owing to her need to pay penance for a past sin.

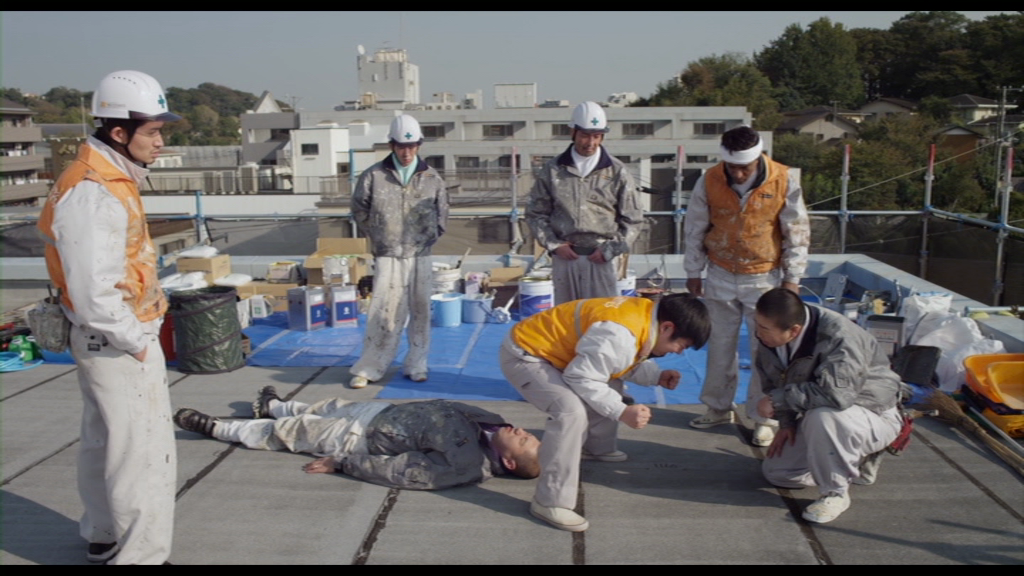

Chiho reflects on what she may have done in the past to deserve such unhappiness. She remembers humiliating Fukuda at school: she led Fukuda on, allowing him to believe that she was romantically interested him, and during one meeting made him close his eyes and prepare for their first kiss. However, unbeknownst to Fukuda, he was actually ‘kissed’ by a severed pig’s head, and the incident was recorded on video camera by the school bullies – with whom Chiho was in league. Fukuda, it seems, never recovered from this incident, and this is the reason behind his distrust in women. Chiho decides to track down Fukuda and apologise to him. However, when she knocks on Fukuda’s door she is inspired by his unconventional looks to take his portrait and begins to plan a book of portraits of Fukuda that is to be called ‘Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats’. However, Chiho must overcome the barriers that Fukuda has put in place towards other people, and especially women, owing to her participation in the targeting of Fukuda by the school bullies approximately twenty years prior.  The film begins with a ‘fart joke’ that establishes Fukuda’s skills as a natural born peacekeeper. Schimacchi has ridiculed Minoru, a new member of the painting and decorating team who has fallen asleep on the job, through awakening him by breaking wind over his face. Fukuda mediates the dispute between these two colleagues, proposing that they reverse the roles and allow Minoru to break wind over the face of Schimacchi. However, Minoru can’t break wind and Fukuda offers to do it in his stead. Following Fukuda’s intervention, Minoru and Schimacchi set aside their differences and dine together, with Fukuda, in a restaurant after work. The film begins with a ‘fart joke’ that establishes Fukuda’s skills as a natural born peacekeeper. Schimacchi has ridiculed Minoru, a new member of the painting and decorating team who has fallen asleep on the job, through awakening him by breaking wind over his face. Fukuda mediates the dispute between these two colleagues, proposing that they reverse the roles and allow Minoru to break wind over the face of Schimacchi. However, Minoru can’t break wind and Fukuda offers to do it in his stead. Following Fukuda’s intervention, Minoru and Schimacchi set aside their differences and dine together, with Fukuda, in a restaurant after work.

Later, Fukuda returns to his home in Fukufuku Flats; the walls of his rooms are decorated with the kites he has designed. However, this sanctity is broken when Nonoshita arrives on Fukuda’s doorstep, asking for Fukuda’s help in dealing with another of their neighbours, Mabuchi, whose pet snake terrifies Nonoshita. Fukuda mediates in this dispute, again showing his skills as a peacekeeper. Mabuchi angrily accuses Nonoshita of being a panty stealer; this is a crime for which Nonoshita is paying his penance by completing the Shikoku Pilgrimage. Fukuda tells Mabuchi, ‘It’s not as if he killed someone. Stealing pants is of course wrong. Don’t be so hard on someone trying to be reborn’. Nonoshita, meanwhile, doesn’t understand why Mabuchi would wish to keep a pet snake: ‘My loneliness isn’t soothed by something cuddly’, Mabuchi asserts in response to Fukuda’s suggestion he should have a more ‘cute and cuddly’ pet to assuage his loneliness instead, ‘I’ve got to shock it numb’. Eventually, Fukuda manages to encourage Nonoshita and Mabuchi to forget their differences and become friends.  The film takes some time away from Fukuda to satirise the art world in which Chiho aspires to become involved. Collecting her award from ‘the great Numakura’, Chiho meets the eccentric photographer, who wears a bizarre self-made camera (one of many in different colours, it seems) around his neck: the device is strangely phallic. Following the sequences depicting Fukuda’s existence as a painter and decorator, the scenes focusing on the artworld seem to place in juxtaposition the eccentricity of Numakura and his type and the drabness of Fukuda’s existence. Later, Numakura offers to mentor Chiho, who has given up her job to follow her dream of becoming a photographer. ‘You’ve given up great money to walk a very hard road’, Numakura tells her, offering to ‘train you hard’ and adding, ‘People say I may have picked you with other intentions’. Numakura asks Chiho what she would do if she was ‘confronted with a drunk’s vomit’ in the street. Chiho tells him she would ‘turn away and walk by without looking’. To this, Numakura tells her, ‘An artist can’t do that. They get close and stare a hole in it. I did it for five hours once [….] At first all I saw was its foulness. As I stared at it though, that vomit transformed into an infinite cloud of stars. As I relished each detail, five hours passed instantly. This visual articulation is art. Someone who can find God in vomit is an artist’. The film takes some time away from Fukuda to satirise the art world in which Chiho aspires to become involved. Collecting her award from ‘the great Numakura’, Chiho meets the eccentric photographer, who wears a bizarre self-made camera (one of many in different colours, it seems) around his neck: the device is strangely phallic. Following the sequences depicting Fukuda’s existence as a painter and decorator, the scenes focusing on the artworld seem to place in juxtaposition the eccentricity of Numakura and his type and the drabness of Fukuda’s existence. Later, Numakura offers to mentor Chiho, who has given up her job to follow her dream of becoming a photographer. ‘You’ve given up great money to walk a very hard road’, Numakura tells her, offering to ‘train you hard’ and adding, ‘People say I may have picked you with other intentions’. Numakura asks Chiho what she would do if she was ‘confronted with a drunk’s vomit’ in the street. Chiho tells him she would ‘turn away and walk by without looking’. To this, Numakura tells her, ‘An artist can’t do that. They get close and stare a hole in it. I did it for five hours once [….] At first all I saw was its foulness. As I stared at it though, that vomit transformed into an infinite cloud of stars. As I relished each detail, five hours passed instantly. This visual articulation is art. Someone who can find God in vomit is an artist’.

Numakura then suggests that both he and Chiho ‘shoot each other’ and get undressed to do so. As Numakura strips naked, Chiho remains embarrassed and unsure. ‘For an artist, not undressing is far more embarrassing than dressing’, Numakura tells her unconvincingly, ‘If you won’t show yourself, the universe won’t show itself to you’. He concludes by asking, ‘You don’t think this is sexual harassment, do you?’ ‘I sort of think it may be’, Chiho responds before hitting Numakura with his bizarre camera and fleeing from his studio.  There’s an odd suggestion that when Chiho encounters Fukuda again with the intention of apologising to him, she sees in his unconventional face her equivalent of the ‘drunk’s vomit’ that Numakura waxed lyrical about in his attempted seduction of Chiho. (Fukuda’s unusual features are communicated excellently through the very physical cross-gender performance of Ôshima Miyuki, a television comedienne usually known for her work with the comedy trio Morisanchu.) ‘There hasn’t been one second that I’ve liked my own face’, Fukuda confesses to Chiho. ‘Nobody knows their own beauty’, she says in response. Chiho wants Fukuda to laugh in his photographic portraits, but Chiho’s initial attempts to get Fukuda to do this result in an expression that seems to connote agony or fear more than joy. Early in their first sitting, Fukuda demonstrates doubts about Chiho’s aims, asking her, ‘When will you be satisfied? Is it that much fun to mock me?’ Chiho suggests that her failure to capture joy in Fukuda’s expression is ‘my fault. I’ve only shot landscapes and stuff’. Certainly, Fukuda is objectified by Chiho’s lens, potentially opening himself to ridicule, something which Schimacchi seems to recognise: as Fukuda begins to fall in love with Chiho, Schimacchi meets with Chiho and asks her to consider her intentions towards Fukuda: ‘You’re looking down on him like a weird bulldog you think is cute’, Schimacchi tells Chiho, ‘That man hasn’t had a woman in thirty years. What’ll happen when a women like you compliments him?’ Schimacchi concludes by telling Chiho that she ‘can’t keep leading him on. He can’t come back from it’. There’s an odd suggestion that when Chiho encounters Fukuda again with the intention of apologising to him, she sees in his unconventional face her equivalent of the ‘drunk’s vomit’ that Numakura waxed lyrical about in his attempted seduction of Chiho. (Fukuda’s unusual features are communicated excellently through the very physical cross-gender performance of Ôshima Miyuki, a television comedienne usually known for her work with the comedy trio Morisanchu.) ‘There hasn’t been one second that I’ve liked my own face’, Fukuda confesses to Chiho. ‘Nobody knows their own beauty’, she says in response. Chiho wants Fukuda to laugh in his photographic portraits, but Chiho’s initial attempts to get Fukuda to do this result in an expression that seems to connote agony or fear more than joy. Early in their first sitting, Fukuda demonstrates doubts about Chiho’s aims, asking her, ‘When will you be satisfied? Is it that much fun to mock me?’ Chiho suggests that her failure to capture joy in Fukuda’s expression is ‘my fault. I’ve only shot landscapes and stuff’. Certainly, Fukuda is objectified by Chiho’s lens, potentially opening himself to ridicule, something which Schimacchi seems to recognise: as Fukuda begins to fall in love with Chiho, Schimacchi meets with Chiho and asks her to consider her intentions towards Fukuda: ‘You’re looking down on him like a weird bulldog you think is cute’, Schimacchi tells Chiho, ‘That man hasn’t had a woman in thirty years. What’ll happen when a women like you compliments him?’ Schimacchi concludes by telling Chiho that she ‘can’t keep leading him on. He can’t come back from it’.

Chiho’s project seems validated by the publication of her book, which is accompanied by a warm party for Fukuda and his friends – and after which Fukuda seems to become something of a celebrity. There’s perhaps the suggestion that like Chiho, the film ‘looks down on’ Fukuda’s curious, unusual features ‘like a weird bulldog you think is cute’ – that Fukuda is to some extent objectified equally by the lenses of Chiho and Fujita, the film’s director. This, along with the film’s depiction of the lasting impact of a moment of childhood cruelty, raises questions that leave the viewer with food for thought once the laughter has subsided. However, like Chiho, Fujita ultimately finds in the lives of Fukuda and his friends a genuine sense of warmth and human companionship that seeps into every frame of the film. The film is uncut and runs for 106:05 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. Shot on digital video, the film has a crisp digital aesthetic which is communicated very nicely on this DVD release. It’s a brightly photographed film, and as with any shot-on-digital video material, the image lacks the dynamic range of material shot on film, but the presentation is true to the source material.   NB. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 5.1 track in Japanese. The track is clear throughout. It’s not a ‘showy’ track by any means, but there’s a richness to the soundscape when there needs to be (for example, the ambient dialogue in the restaurant scene near the beginning of the film). The optional English subtitles are grammatically correct and easy to read – though a couple of minor typographical errors slip in here and there (Numakura’s name is presented as Namakura on at least one occasion). Disc menus are also available in Italian and German, with optional subtitles for the main feature in those languages too.

Extras

The disc includes: - an introduction by the director Fujita Yosuke (0:54). In this introduction, Fujita foregrounds his intention to craft a ‘human comedy’ with a ‘serious side’. - an interview with Fujita Yosuke (16:36). This interview focuses on the reasons for the gap between the production of Fujita’s first film and this picture, the origins of the film’s narrative, the logistics of having the busy television performer Ôshima Miyuki star as Fukuda, Fujita’s feelings towards Ôshima’s performance in the film, and Fujita’s ongoing working relationship with Arakawa Yoshiyoshi. Fujita comments in Japanese, with accompanying English subtitles. - a discussion with actress Ôshima Miyuki, director Fujita Yosuke and producer Adam Torel (18:57). This panel discussion at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. The origins of the film are examined, as are the logistics of producing the film. This discussion takes place in a mixture of English and Japanese – with the Japanese language comments subtitled in English. - the film’s trailer (2:07).

Overall

Fujita’s approach to his material could be described as ‘bittersweet’ – though the balance arguably skews more towards the ‘sweet’ than the ‘bitter’, as with Fujita’s Fine, Totally Fine. Like Fujita’s directorial debut, Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats tells a warm, human story that is riddled with some genuinely funny moments. It’s an utterly endearing film, filled with good humour, that fits into the exploration of freeter lifestyles that Fujita, along with a number of other Japanese filmmakers of the era, has made his own. The presentation of the picture on this DVD is very good, true to the shot-on-digital video aesthetic of the film itself, and there’s some solid contextual material to boot. Fujita’s approach to his material could be described as ‘bittersweet’ – though the balance arguably skews more towards the ‘sweet’ than the ‘bitter’, as with Fujita’s Fine, Totally Fine. Like Fujita’s directorial debut, Fuku-Chan of Fukufuku Flats tells a warm, human story that is riddled with some genuinely funny moments. It’s an utterly endearing film, filled with good humour, that fits into the exploration of freeter lifestyles that Fujita, along with a number of other Japanese filmmakers of the era, has made his own. The presentation of the picture on this DVD is very good, true to the shot-on-digital video aesthetic of the film itself, and there’s some solid contextual material to boot.

References: Berra, John, 2012: ‘Introduction by the Editor’. In: Berra, John (ed), 2012: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books: 7-10

|

|||||

|