|

|

3 Women

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th July 2015). |

|

The Film

3 Women (Robert Altman, 1977) 3 Women (Robert Altman, 1977)

After M*A*S*H (1970), Robert Altman’s star as a director seemed to be on the ascendence within Hollywood, and Altman was approached to direct a number of big budget pictures. However, he chose instead to make the low-key allegorical comedy Brewster McCloud (1970). Then in the early 1970s, he delivered a series of critically acclaimed films that nevertheless had limited commercial appeal, such as Images (1972) and McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971). Nashville (1975) reasserted Altman’s position as a director of note to the Hollywood establishment, but the films Altman made immediately after Nashville – including Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), 3 Women (1977) and A Wedding (1978) – were experimental pictures that again alienated Hollywood owing to their lack of commercial success. Altman’s output in the 1970s was topped off by the poorly-received, both critically and commercially, Popeye in 1980. Charles Warren has suggested that along with Buffalo Bill and the Indians and Quintet (1979), 3 Women ‘gave Altman the reputation of an art film director’ which led to ‘large budget productions [being] not viable [for Altman] for a time’ (Warren, 2013: 27). Like Altman’s subsequent four pictures (A Wedding; Quintet; A Perfect Couple; 1979; and H.E.A.L.T.H., 1979), 3 Women was financed by Alan Ladd Jr for Lion’s Gate Films. Altman reputedly approached Ladd by rushing into Ladd’s office after experiencing a vivid dream that would form the basis for the narrative of 3 Women: Altman had with him ‘a 30-page outline, a cast list and [his] willingness to work with the relatively low budget’ (Stabiner, 1977: 57). Ladd’s decision to finance the picture was intended to capitalise on the trend in the production of ‘women’s films’ that took place at the end of the 1970s, many of which examined issues of female independence – although sometimes within an arguably exploitative framework that saw female characters ‘punished’ for their transgressions (as in Richard Brooks’ 1977 adaptation of Judith Rossner’s novel Looking for Mr Goodbar). However, Altman was critical of Alan Ladd Jr’s perspective, saying that producing the film because of its potential to tap into the market for ‘women’s films’ was inherently exploitative and ‘no different from the thinking that produced black exploitation films like Superfly’ (Altman, quoted in Ferrari, 1990: 12). Nevertheless, owing to Altman’s ability to deliver a film cheaply, Ladd allowed Altman to work with little to no studio interference. When the completed picture was screened for Ladd, Altman later claimed, Ladd told Altman, ‘Well, I don’t know who you think you’re going to sell this picture to, but good luck’ (Ladd, quoted in Biskind, 1998: 341).  3 Women opens in the Desert Springs Rehabilitation and Geriatrics Centre, where new employee Pinky Rose (Sissy Spacek) is introduced to her colleagues, including Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall). Millie is eager to impress upon others her popularity with men but sadly this is almost wholly fantasy: when Millie speaks, others invariably ignore her. However, Pinky clearly idolises Millie; when Millie’s roommate Deirdre (Beverly Ross) moves out to live with her fiancé and Millie advertises for a new roommate, Pinky seizes her chance to get closer to Millie. Pinky spends her time absorbing Millie’s company and, when Millie goes out, reading Millie’s diary. Meanwhile, Millie treats Pinky patronisingly, criticising her and ordering her about. 3 Women opens in the Desert Springs Rehabilitation and Geriatrics Centre, where new employee Pinky Rose (Sissy Spacek) is introduced to her colleagues, including Millie Lammoreaux (Shelley Duvall). Millie is eager to impress upon others her popularity with men but sadly this is almost wholly fantasy: when Millie speaks, others invariably ignore her. However, Pinky clearly idolises Millie; when Millie’s roommate Deirdre (Beverly Ross) moves out to live with her fiancé and Millie advertises for a new roommate, Pinky seizes her chance to get closer to Millie. Pinky spends her time absorbing Millie’s company and, when Millie goes out, reading Millie’s diary. Meanwhile, Millie treats Pinky patronisingly, criticising her and ordering her about.

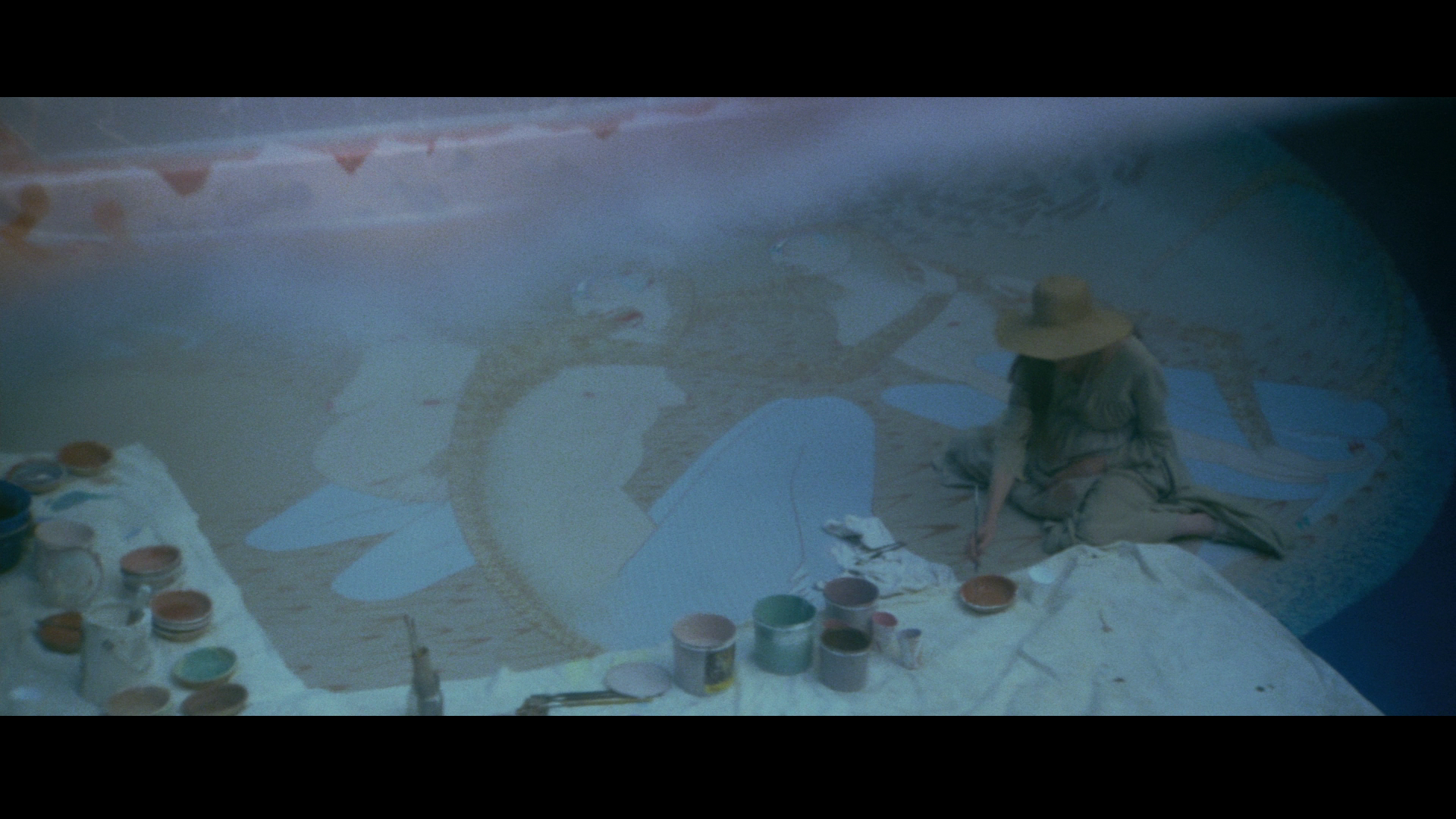

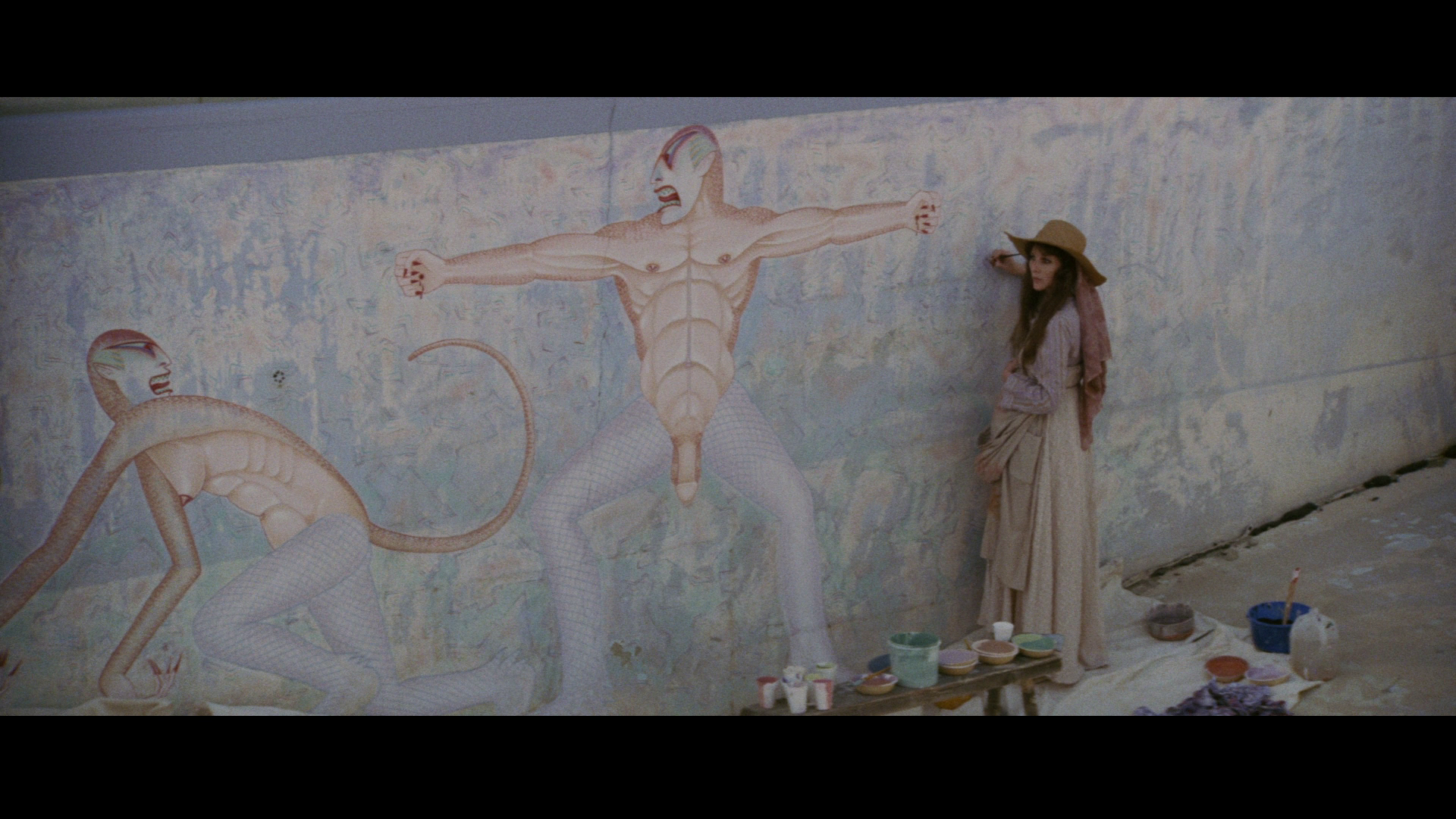

Millie takes Pinky to Dodge City, a Wild West-themed showground – with a bar and a gun range – that is owned by Edgar (Robert Fortier) and Willie (Janice Rule), the same couple who own the residential motel, Purple Sage Apartments, in which Pinky and Millie live. (Edgar is a has-been whose claim to fame is that, in the words of Millie, he ‘used to be on the Wyatt Earp TV show. He knows Hugh O’Brien’.) The silent Willie is pregnant and spends her time painting frescoes in the drained swimming pools at both Dodge City and the motel: these frescoes depict three grotesque serpent-like females tearing at each other’s throats, presided over by a well-endowed male figure. Seemingly desperate for male company, Millie returns home one evening, drunk and in the company of Edgar. Millie treats Pinky coldly, eventually screaming at her to leave. Upset by this treatment from her idol, Pinky throws herself into the motel’s swimming pool – seemingly in an attempt to commit suicide. She is rescued by some of the other inhabitants of the motel. Pinky is in a coma; ridden with guilty, Millie goes to great lengths to contact Pinky’s parents, who live in Texas, and get them to travel to see Pinky. However, when Pinky awakens from her coma, she claims that the people Millie believes to be her parents aren’t her parents after all.  Moving back in with Millie for her recuperation period, Pinky demonstrates some curious changes in her character: she has taken up smoking and drinking, and seems much more aggressive than before. She also seems to have begun an affair with Edgar. Millie confronts Pinky, but Pinky seems unsure of who she is: she questions why Millie keeps calling her Pinky, insisting that she is instead Millie Lammoreaux. One night, Willie goes into labour, with inevitably tragic results. Moving back in with Millie for her recuperation period, Pinky demonstrates some curious changes in her character: she has taken up smoking and drinking, and seems much more aggressive than before. She also seems to have begun an affair with Edgar. Millie confronts Pinky, but Pinky seems unsure of who she is: she questions why Millie keeps calling her Pinky, insisting that she is instead Millie Lammoreaux. One night, Willie goes into labour, with inevitably tragic results.

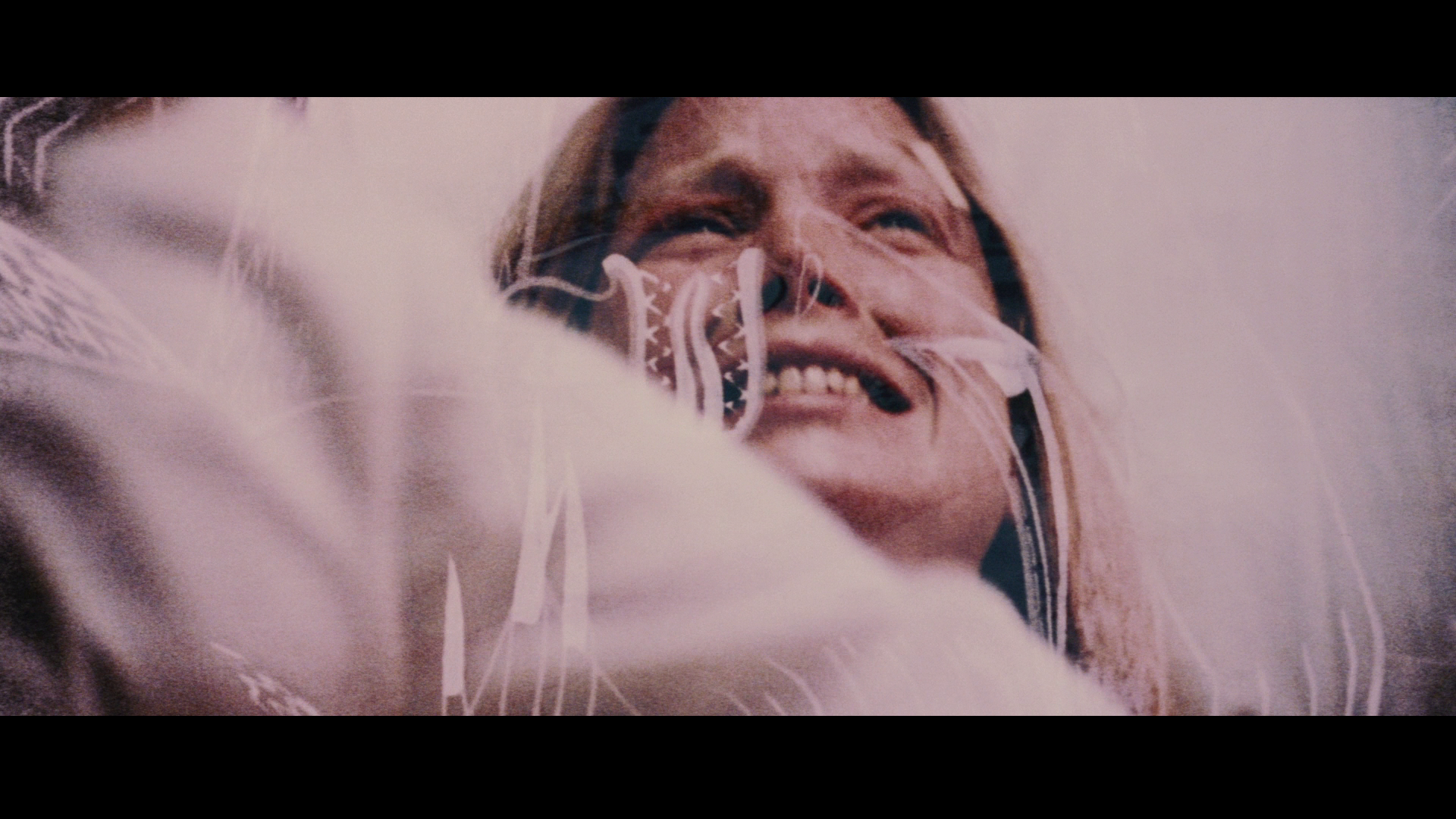

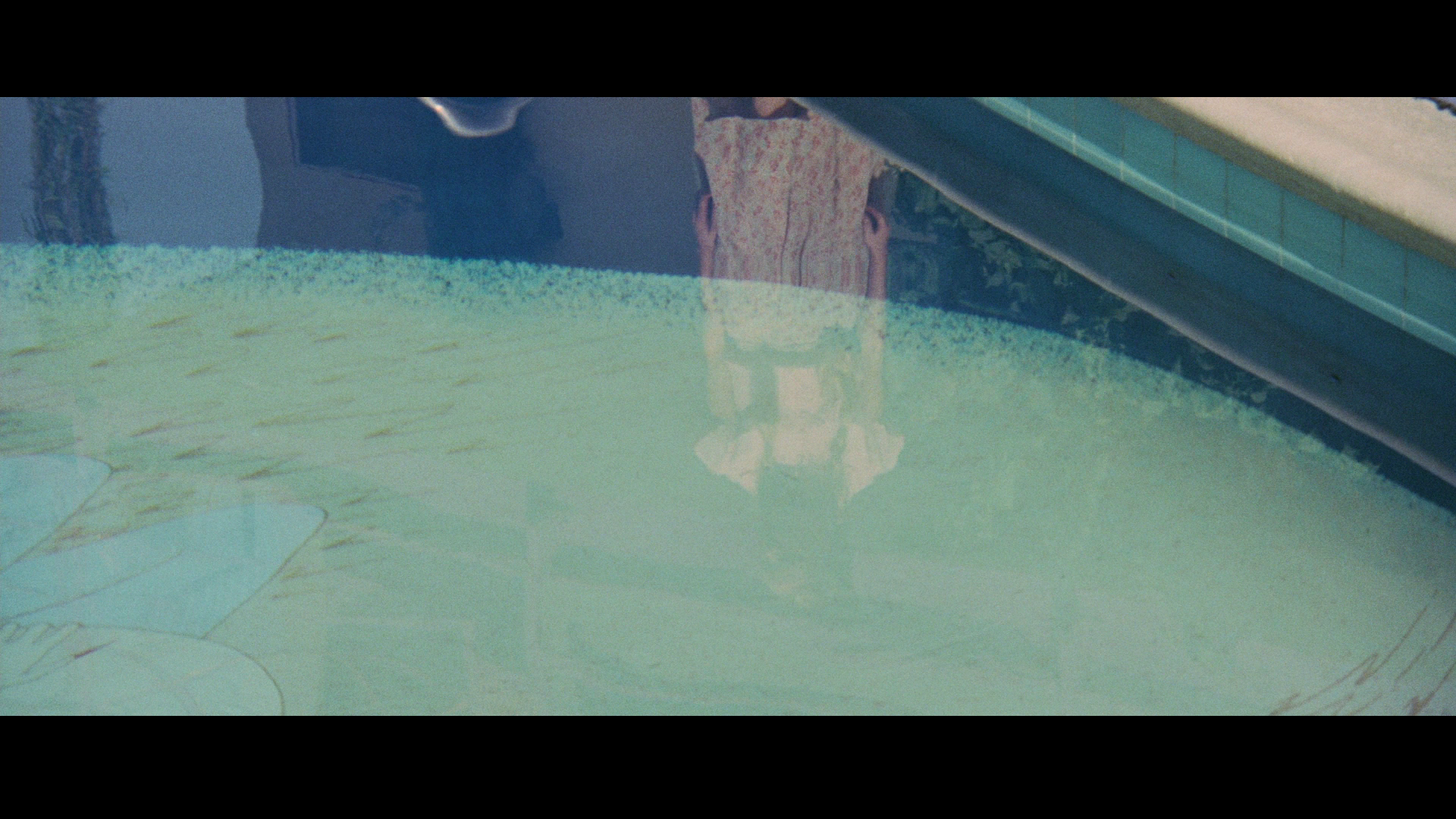

The film is filled with symbolism. The swimming pools are suggestive of birth and rebirth, and are connected to Willie’s pregnancy (she’s often seen in the bottom of the drained swimming pools, painting her frescoes or simply adding to them). Furthermore, the swimming pools are used for therapeutic purposes within the Desert Springs centre. Millie and Pinky first see one another across the swimming pool at Desert Springs; and Millie first encounters Willie in the bottom of the drained swimming pool at Dodge City, painting one of her frescoes. In one sequence, Pinky looks out the window of her and Millie’s home in the Purple Sage Apartments and sees Willie adding to the fresco she has painted on the bottom of the drained swimming pool there; the camera is positioned behind the fish tank that sits in front of the window, the water in the bowl obscuring our view of Willie – who takes up the same space within the composition as the ornamental Creature from the Black Lagoon statuette that is within the fish tank. The image foreshadows Pinky’s attempt to drown herself in the same swimming pool whilst also alluding symbolically to Willie’s pregnancy.  Though a number of Altman’s films (including Images, 3 Women and later films such as Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, 1982) focus on women and their relationship with the worlds around them, Robert Phillip Kolker reminds us that these pictures ‘must be understood as films about women from the point of view of a particular male’ (Kolker, 2011: 411). Reflecting this viewpoint, Robin Wood suggested in Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan that within 3 Women explores a relevant issue (‘that women conditioned by our culture, however seemingly independent, might not be able to escape entrapment in familial roles and structures’) but simplistically depicts the female characters ‘as victims, yes, but primarily of their own innate stupidity’ – that Altman’s conception of woman is ‘as victim’ and defined by ‘masochism and self-punishment’ – which makes them part of the same stream of ‘women’s pictures’ as films like Looking for Mr Goodbar (Wood, 2003: np).  David Thomson once suggested that 3 Women ‘starts off like a breakthrough, but then succumbs to florid illusions of poetry, dream, and the mystical sisterhood of glum women’ (Thomson, 2010: np). Certainly, there’s tension (intentional) between the satirical first half of the film and its nebulous, nightmarish second half. Gerald Busby’s eerie, unsettling score for the picture (dominated by woodwind and string instruments, and which has the qualities of a horror film score) suggests a sense of impending doom that hangs over the film from its opening frames; it is complemented by Altman’s characteristic use of the longer end of a zoom lens, which through its flattening of perspective indicates that we are eavesdropping on the lives of the characters in the film, watching the events voyeuristically from a distance. However, though its humour is undercut by these two devices, the first half of the film is fairly light in tone, observing Pinky and Millie’s developing relationship. (Altman once joked that Pinky and Millie could be considered an almost vaudevillian double act, jokingly suggesting a title for a sequel to the film: ‘Pinky and Millie Move to the City’; Altman, quoted in Gabbard & Gabbard, 1999: 225.) From the outset, as she watches Millie at work and the Desert Springs establishment, Pinky has adoring eyes for her slightly more mature ‘double’. David Thomson once suggested that 3 Women ‘starts off like a breakthrough, but then succumbs to florid illusions of poetry, dream, and the mystical sisterhood of glum women’ (Thomson, 2010: np). Certainly, there’s tension (intentional) between the satirical first half of the film and its nebulous, nightmarish second half. Gerald Busby’s eerie, unsettling score for the picture (dominated by woodwind and string instruments, and which has the qualities of a horror film score) suggests a sense of impending doom that hangs over the film from its opening frames; it is complemented by Altman’s characteristic use of the longer end of a zoom lens, which through its flattening of perspective indicates that we are eavesdropping on the lives of the characters in the film, watching the events voyeuristically from a distance. However, though its humour is undercut by these two devices, the first half of the film is fairly light in tone, observing Pinky and Millie’s developing relationship. (Altman once joked that Pinky and Millie could be considered an almost vaudevillian double act, jokingly suggesting a title for a sequel to the film: ‘Pinky and Millie Move to the City’; Altman, quoted in Gabbard & Gabbard, 1999: 225.) From the outset, as she watches Millie at work and the Desert Springs establishment, Pinky has adoring eyes for her slightly more mature ‘double’.

Millie perceives herself as popular, with her colleagues at Desert Springs and with men, but Altman demonstrates considerable irony towards Millie’s sense of identity. Millie talks and talks but no-one listens. At work, she rambles to her work colleagues, but they ignore her. At lunchtime, she chooses to dine in the refectory of the local hospital, sitting at a table with the doctors; she is followed there by the adoring Pinky, who watches as Millie attempts to converse with the doctors, but like Millie’s work colleagues they ignore her. Returning to Purple Sage Apartments with Pinky, Millie attempts to flirt with one of her neighbours, Tom, but he too ignores her. Pinky asks Millie if Tom is her boyfriend, and Millie replies, ‘He’d like to be. He’s always asking me out and everything. But I ain’t going to go out with him until he gets rid of that cold’. Millie’s response is a difficult-to-digest excuse for the cold shoulder she has received from Tom – difficult to digest for everyone except the admiring Pinky, it seems. Millie tells Pinky that ‘I plan everything. I figure out what it is I want, and then I set to it’, but Millie seemingly never achieves anything and does very little.  David Thomson has suggested that Millie has a personality that is ‘as unstable and grating as a marble on a hard floor’ (Thomson, 2010: np). Out of her mouth spill clichés and the received wisdom of women’s magazines, suggesting the extent to which Millie’s consciousness has been colonised by romantic myths – when the reality of her existence is much more depressing, and the only relationship she has with a man is an illicit affair with the sleazy has-been Edgar. In interview, Altman suggested that Millie is ‘a victim of women’s magazines and movies and everyone around her. She just repeats things that she thinks will make people like her, but she’s totally alone’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2006: 40). When Deirdre returns to town with her fiancé and some friends in tow, they promise to come over to Millie’s apartment for dinner. Millie makes an effort to prepare what she thinks is a spectacular dinner party for Deirdre and her entourage, waxing lyrical to Pinky about how everybody thinks her dinner parties are the best they’ve ever attended. In reality, most of the food that Millie prepares is prepackaged and processed; but even more tragically, at the last minute Deirdre and her friends inform Millie, via Pinky, that they have decided instead to spend the night in Dodge City instead. David Thomson has suggested that Millie has a personality that is ‘as unstable and grating as a marble on a hard floor’ (Thomson, 2010: np). Out of her mouth spill clichés and the received wisdom of women’s magazines, suggesting the extent to which Millie’s consciousness has been colonised by romantic myths – when the reality of her existence is much more depressing, and the only relationship she has with a man is an illicit affair with the sleazy has-been Edgar. In interview, Altman suggested that Millie is ‘a victim of women’s magazines and movies and everyone around her. She just repeats things that she thinks will make people like her, but she’s totally alone’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2006: 40). When Deirdre returns to town with her fiancé and some friends in tow, they promise to come over to Millie’s apartment for dinner. Millie makes an effort to prepare what she thinks is a spectacular dinner party for Deirdre and her entourage, waxing lyrical to Pinky about how everybody thinks her dinner parties are the best they’ve ever attended. In reality, most of the food that Millie prepares is prepackaged and processed; but even more tragically, at the last minute Deirdre and her friends inform Millie, via Pinky, that they have decided instead to spend the night in Dodge City instead.

When Pinky is introduced, she is childlike and innocent, blowing bubbles in her cola during her break from work and playing with a wheelchair like a child. Discovering that Millie’s surname is Lammoreaux, Pinky naïvely asks, ‘Are you French?’ ‘No, American’, Millie responds in her utterly humourless manner. Blind to Millie’s delusions about her own popularity, Pinky worships Millie, telling another colleague, ‘She sure is nice, isn’t she? [….] Just seems like she always does everything right’. Later, after she has moved into Millie’s apartment, Pinky tells Millie directly, ‘You know what? [….] You’re the most perfect person I ever met’. However, frustrated by Deirdre’s snub over the dinner party, Millie vents her anger on Pinky, telling her, ‘Ever since you moved in here, you’ve been causing me grief. Nobody wants to hang around you. You don’t drink, you don’t smoke, you don’t do anything you’re supposed to’. Millie’s criticism of Pinky immediately precedes Pinky’s attempt on her own life. Following this, the satirical aspects of the first half of the film evolve into a nightmarish narrative about the loss of control over one’s own sense of self. When Pinky returns from the hospital after awakening from her coma, one of the earliest indicators that something is amiss – that her and Millie’s identities are in effect overlapping – is, apart from her snippy attitude, the fact that she begins to smoke cigarettes. From the beginning, Millie and Pinky’s relationship is defined by the enactment of various roles: as Millie offers Pinky some on-the-job training at Desert Springs, she suggests to Pinky that they should take part in some role playing: ‘You’re gonna play the patient and I’ll play the carer’, she says. Millie and Pinky share similar roots. As one of the doctors says, Millie and Pinky have something in common: they are both from Texas. They are also both called Mildred. When Pinky first meets Edgar, she tells him that Pinky is a nickname and ‘My real name’s Mildred, but I hate it’. In response to this, Millie rolls her eyes subtly. Later, Millie asks Pinky, ‘How come you didn’t tell me your name was Mildred?’ ‘Because I hate it’, Pinky responds. ‘Well, what do you think my name is?’, Millie asks. ‘Millie’, Pinky answers innocently. Millie cocks her head. ‘Oh’, Pinky declares, suddenly aware of her faux-pas. ‘“Oh”, yeah’, Millie asserts humourlessly.  Later, after Pinky awakens from her coma following her suicide attempt, the confusion of the two Mildreds becomes more severe. Millie goes to great lengths to contact Pinky’s parents, who travel from Texas to see their daughter. They stay in Millie and Pinky’s apartment whilst the comatose Pinky is in intensive care, and one evening Millie’s loneliness is reinforced when, looking through the bedroom door (Millie is sleeping on a makeshift bed in the living room), she sees the elderly couple engaged in what seems to be a sexual embrace. When Pinky awakens from her coma and sees Mr and Mrs Rose, she asserts, ‘They’re not my parents’. (Through the cold insistence of Pinky’s declaration and the mental confusion of Mr Rose, in particular, Altman seems to leave open the question as to whether or not this elderly couple are in fact Pinky’s parents.) Shortly after this, Pinky screams at Millie, ‘Don’t call me Pinky!’ Later, after Pinky awakens from her coma following her suicide attempt, the confusion of the two Mildreds becomes more severe. Millie goes to great lengths to contact Pinky’s parents, who travel from Texas to see their daughter. They stay in Millie and Pinky’s apartment whilst the comatose Pinky is in intensive care, and one evening Millie’s loneliness is reinforced when, looking through the bedroom door (Millie is sleeping on a makeshift bed in the living room), she sees the elderly couple engaged in what seems to be a sexual embrace. When Pinky awakens from her coma and sees Mr and Mrs Rose, she asserts, ‘They’re not my parents’. (Through the cold insistence of Pinky’s declaration and the mental confusion of Mr Rose, in particular, Altman seems to leave open the question as to whether or not this elderly couple are in fact Pinky’s parents.) Shortly after this, Pinky screams at Millie, ‘Don’t call me Pinky!’

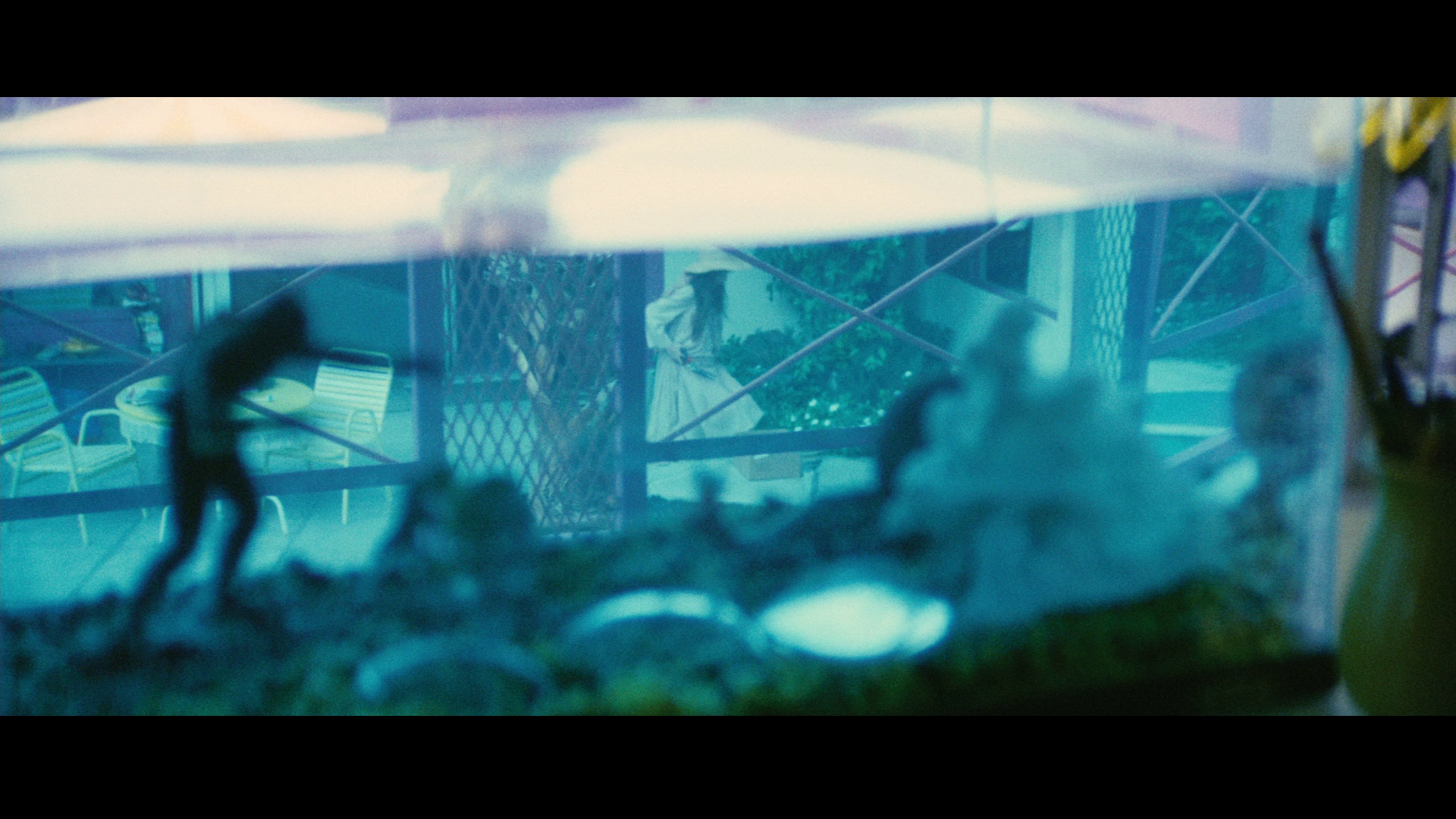

After being released from the hospital and, in the apparent absence of any relatives, put into the care of Millie, Pinky begins to exhibit more unusual changes in her behaviour. She takes up smoking and, whereas before she was sexually naïve, asserts to Millie, ‘God, I hope I’m not pregnant’, suggesting that in the hospital, Dr Norton may have taken advantage of her – but ‘How am I supposed to know? I was drugged all the time’. She also begins to arrange secret rendez-vous with Edgar, taking Millie’s car and driving it to Dodge City – much to the chagrin of Millie, who reports the theft of her car to the police and is embarrassed when the police reveal to her that her car was taken by Pinky. At the Purple Sage Apartments, Pinky begins to find the popularity with the male neighbours that Millie has always desired, leading Millie to become jealous of her friend. Finally, Pinky snaps when Millie addresses her as Pinky once more. ‘Will you stop calling me that?’, Pinky yells, ‘How many times do I have to tell you my name is Mildred? You got that? It’s Mildred!’ Pinky now claims herself to be Millie Lammoreaux, much to the confusion of Millie. 3 Women was heavily influenced by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), in terms of the focus on the shifting identities between Pinky, Millie and Willie – which mirrors the confusion of Elizabeth and Alma’s identities in Bergman’s film. Where, commenting on Persona, Susan Sontag suggested that Elizabeth and Alma may be perceived as ‘two mythical parts of a single “person”’, Pinky, Millie and Willie may also be interpreted as the same woman – or stages in an individual woman’s life (Sontag, 1967: np). Like Raphael’s painting ‘The Three Graces’ (1504/5), 3 Women may be seen as a depiction of the three stages of womanhood: Pinky is the naïve adolescent, eager to please; Millie is the vivacious and flirtatious twentysomething, struggling to find her way in the world and appearing pathetic because of it; and Willie is the mature woman, the mother, whose independence and personality have been subdued by patriarchy (represented through her philandering husband Edgar) and whose only form of self-expression seems to be the frescoes she paints. Willie’s enigmatic nature is also communicated by her silence: apparently, more dialogue was written for Willie but Altman decided to cut, in order to make the character more mysterious (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2006: 40).  As if to reinforce the suggestion that these three women are flipsides of the same coin, like Bergman in Persona Altman uses visual doubling throughout 3 Women, filling the frame with shots containing reflections of Pinky, Millie and Willie in mirrors or panes of glass. When Millie is first introduced to Pinky, we see Millie talking to her colleagues in the locker room of Desert Springs whilst Pinky watches on, her face reflected in a mirror; later, when Millie takes Pinky in as her co-tenant, Millie again talks whilst we see, reflected in the mirror on the dressing table, Pinky staring intently. (As Millie and Pinky begin to switch roles following Pinky’s suicide attempt, Altman repeats this framing but reverses the positioning of the two women.) As if to reinforce the suggestion that these three women are flipsides of the same coin, like Bergman in Persona Altman uses visual doubling throughout 3 Women, filling the frame with shots containing reflections of Pinky, Millie and Willie in mirrors or panes of glass. When Millie is first introduced to Pinky, we see Millie talking to her colleagues in the locker room of Desert Springs whilst Pinky watches on, her face reflected in a mirror; later, when Millie takes Pinky in as her co-tenant, Millie again talks whilst we see, reflected in the mirror on the dressing table, Pinky staring intently. (As Millie and Pinky begin to switch roles following Pinky’s suicide attempt, Altman repeats this framing but reverses the positioning of the two women.)

At Desert Springs, there are two twins amongst the staff, whose appearance within the film underscores the theme of doubling. When Pinky sees them for the first time, a haunted expression crosses her face and Millie asks her, ‘What’s the matter? Ain’t you ever seen twins before?’ (Millie is told by another colleague, ‘We don’t like the twins. You’ll learn about them soon enough’ – though the reason for the ostracisation of the twins is never fully explained within the film.) Later in the film, prior to her transformation into Millie, Pinky questions the issue of identity by referencing the twins who work at Desert Springs; the dialogue foreshadows the confusion of Millie and Pinky’s identities that takes place later in the narrative. Driving in Millie’s car, Pinky says, ‘I wonder what it’s like to be twins’. ‘Bet it’d be weird’, Millie responds, clearly disengaged from the conversation and perplexed by Pinky’s imaginings. ‘Do you think they know which one they are?’, Millie asks. ‘Sure they do’, Millie responds, ‘They’d have to, wouldn’t they?’ ‘I don’t know’, Pinky offers, ‘Maybe they switch back and forth. You know, one day Peggy’s Polly, and another day Polly’s Peggy. Who knows?’ Altman himself once referred to 3 Women as a film about ‘personality theft’, and as the film’s narrative progresses, the identities of these three women/stages of womanhood overlap and become confused: Pinky ‘matures’ into Millie, and Millie develops into Willie (Altman, quoted in Horeck, 2000: 10).   Long unavailable on home video, apparently owing to issues surrounding music rights – an issue which also plagues Altman’s excellent California Suite (1974) and H.E.A.L.T.H. – 3 Women is here presented uncut, and with a running time of 123:37 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 33Gb of space on a dual-layered disc, the 1080p presentation of the film, in the film’s original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, on this Blu-ray release from Arrow (based on a new 4k restoration by Twentieth Century Fox) is noticeably different to the presentation of the film that has been released on Blu-ray in America by Criterion, with Arrow’s new release featuring a slightly different use of colour (dominated by yellows) and Criterion’s presentation offering a more naturalistic palette. Arrow’s presentation also features a little more information on the left and right-hand sides of the frame. Taking up approximately 33Gb of space on a dual-layered disc, the 1080p presentation of the film, in the film’s original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, on this Blu-ray release from Arrow (based on a new 4k restoration by Twentieth Century Fox) is noticeably different to the presentation of the film that has been released on Blu-ray in America by Criterion, with Arrow’s new release featuring a slightly different use of colour (dominated by yellows) and Criterion’s presentation offering a more naturalistic palette. Arrow’s presentation also features a little more information on the left and right-hand sides of the frame.

Altman’s films have notoriously had problems with their home video releases, owing to issues with music rights and problems in conveying Altman’s favouring of fairly radical photographic techniques. As with the experimental photography in some of Altman’s other films (eg, the flashing of the negatives used to shoot The Long Goodbye and McCabe and Mrs Miller, combined with the use of heavy fog filters), Chuck Rosher’s photography for 3 Women also used some radical techniques. The film was overexposed by ‘up to three stops, and then printed […] in the lab to give it a desaturated look’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2006: 41). Kodak’s advice for their motion picture films suggests that ‘pulling’ film (overexposing a negative) results in reduction in contrast, and ‘a slight color bias (yellow shadows and blue highlights)’ (Kodak, No Year: np). 3 Women was also shot in a sun-drenched context using Altman’s favoured combination of (predominantly) zoom lenses and multiple cameras with softer, more ambient lighting which allowed Altman to pick up shots without worrying too much about his actors hitting specific marks – giving a spontaneity and fluidity to their performances. Given this, and the ‘pulling’ of the film stock, in theory the film should have softer contrast and ‘thinner’ blacks, but blacks often look rather bold and slightly crushed in this presentation, and there’s little of the desaturated look that Altman mentioned in interviews about the film. The imagery seems a little too bold and stark, as if the contrast has been dialed up in the creation of this new master to compensate for the overexposed appearance of the film’s negative.  Given the film’s setting in the Californian sun, the slightly golden hue of this presentation seems to fit the material (the mise-en-scène is dominated by tones of yellow anyway, much as the mise-en-scène of Altman’s California Split had featured an abundance of yellows, gold and browns) but sometimes results in the actors looking slightly jaundiced. The experience is a little like watching the film with polarized sunglasses on, comparable to the differences between earlier home video presentations of John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) and the ‘Deluxe Edition’ that was released on DVD in 2007 – or between the remastered 2014 Blu-ray release of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and the previous DVD and Blu-ray releases of that film in Britain and America. Like those releases, this presentation of 3 Women is bound to have both its supporters and detractors. Given the film’s setting in the Californian sun, the slightly golden hue of this presentation seems to fit the material (the mise-en-scène is dominated by tones of yellow anyway, much as the mise-en-scène of Altman’s California Split had featured an abundance of yellows, gold and browns) but sometimes results in the actors looking slightly jaundiced. The experience is a little like watching the film with polarized sunglasses on, comparable to the differences between earlier home video presentations of John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972) and the ‘Deluxe Edition’ that was released on DVD in 2007 – or between the remastered 2014 Blu-ray release of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and the previous DVD and Blu-ray releases of that film in Britain and America. Like those releases, this presentation of 3 Women is bound to have both its supporters and detractors.

That said, despite the slightly ‘crushed’ appearance that seems to be created by boosted contrast within the master, Arrow’s handling of the master itself is characteristically exceptional. A thoroughly robust encode ensures the presentation resolves the grain and detail superbly, resulting in an organic film-like image. Some vignetting is evident throughout the film, most likely a characteristic of the zoom lenses used to shoot the picture; this probably seems a little more noticeable on the Arrow release owing to the fact that Arrow’s presentation offers a little more information on the left and right-hand sides of the frame in comparison with Criterion’s Blu-ray presentation. I’m not sure that one can state definitively in relation to Arrow and Criterion’s discs that one presentation is more ‘accurate’ than the other, without making prejudicial judgements based upon supposition and conjecture. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. However, Fox’s new 4k master of the film doesn’t look an awful lot like a film that has been overexposed by three stops or shot with saturated ambient light to facilitate Altman’s characteristically improvisational use of the zoom lenses he favoured: the contrast looks a little too bold for that. On the other hand, the dominance of yellow within the photography has a precedent within Altman’s filmography (in terms of the photography of California Split) and may very well be closer to Altman’s intentions in this regard than the Criterion disc. Whilst Fox’s master may be flawed, Arrow’s handling of it certainly isn’t; and whilst I’m not going to be brazen enough to suggest that one presentation or the other is ‘definitive’ (this seems to be a case of swings and roundabouts), the differences are substantial enough that Altman’s more rabid fans will probably want to own both presentations. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track (in English, naturally). It’s a rich, deep track with excellent range that is clear throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The film is accompanied on the disc by: - an interview with Shelley Duvall (5:45). This interview with the reclusive Duvall, conducted at Cannes in 1977, features Duvall reflecting on her work with Altman and his methods in directing actors. - ‘David Thompson on 3 Women’ (37:06). This new extended interview with Thompson, the editor of Altman on Altman, features Thompson discussing Altman’s work, with a specific focus on 3 Women. - three image galleries: -- ‘Behind the Scenes’ (1:02). This gallery contains images from the production of the film. -- ‘Cannes Film Festival’ (0:03). This is a very brief gallery of images from the film’s appearance at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival. -- ‘Promotional Images’ (0:16). This gallery includes some of the artwork used to promote the film. - Trailer (1:27).

Packaging

The disc is packaged in an Amaray case that includes reversible artwork and a booklet. As with Arrow’s other booklets, the booklet in this release is lovingly-constructed, illustrated with stills from the film, and features new writing about the film by David Jenkins along with excerpts from David Thompson’s excellent book Altman on Altman.

Overall

As a big fan of Altman’s 1970s films (his California Split is one of my favourite films of all time), I’m delighted to see this Blu-ray release of the far too little-seen 3 Women. Altman’s films often explore the relationships between outsiders and society, and that’s certainly the case here. However, the film itself can best be understood within the framework of the ‘women’s pictures’ of the 1970s, pictures that explored changing roles for women and often featured female protagonists negotiating their newfound independence. Nevertheless, as noted above it’s a story about women that is most definitely filtered through a male (Altman’s) perspective. In the film, women are associated with mysticism and myth (the frescoes painted by Willie), suggesting their unknowability – both to others and to themselves. As a big fan of Altman’s 1970s films (his California Split is one of my favourite films of all time), I’m delighted to see this Blu-ray release of the far too little-seen 3 Women. Altman’s films often explore the relationships between outsiders and society, and that’s certainly the case here. However, the film itself can best be understood within the framework of the ‘women’s pictures’ of the 1970s, pictures that explored changing roles for women and often featured female protagonists negotiating their newfound independence. Nevertheless, as noted above it’s a story about women that is most definitely filtered through a male (Altman’s) perspective. In the film, women are associated with mysticism and myth (the frescoes painted by Willie), suggesting their unknowability – both to others and to themselves.

Whilst there’s much humour in the first half of the film, the general impression that the film as a whole leaves is deeply unsettling – more like a horror film than anything else. Altman himself stated that his aim with the film was to generate in the audience ‘an element of inner fear’ but deliberately trying to prevent the actors from ‘portraying that weird quality. Trying to keep them very mundane and ordinary and let the audience feel that undercurrent from inanimate objects’ (Altman, quoted in Stabiner, 1977: 59). It’s a troubling film that some may find frustratingly ambiguous – but which rewards the patient viewer. The presentation of the film on this disc is very good, though the contrast on the master provided to Arrow by Fox seems a little unnatural for a film that was supposedly shot on stock that was overexposed by three stops and which featured much use of ambient lighting on the set. Nevertheless, Arrow’s handling of the master is characteristically strong. It’s certainly an interesting presentation of the film, different to that released by Criterion in the US; the slight yellow ‘push’ may or may not be closer to Altman’s original intentions. However, to assert that one presentation is more ‘accurate’ than the other in the absence of any hard evidence would be churlish. Certainly, the Arrow release provides a presentation of the film which evidences a level of detail and depth well above that offered by the film’s various DVD releases, and includes a more than satisfying array of contextual material. (Finally, please, Arrow, work your magic on California Split! Pretty please with sugar on top!) References: Biskind, Peter, 1998: Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-and-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. New York: Simon & Schuster Ferrari, Lilie, 1990: ‘ALTMAN, Robert’. In: Kuhn, Annette (ed), 1990: The Women’s International Companion to Film. London: Virago Press: 12 Gabbard, Glen O & Gabbard, Krin, 1999: Psychiatry and the Cinema. Washington: American Psychiatric Press (Second Edition) Horeck, Tanya, 2000: ‘Robert ALTMAN’. In: Allon, Yoram et al (eds), 2000: Contemporary North American Film Directors. London: Wallflower Press: 8-11 Kodak, No Year: ‘Push/Pull Processing’. [Online.] http://motion.kodak.com/motion/support/technical_information/processing_information/push.htm Kolker, Robert Phillip, 2011: A Cinema of Loneliness. Oxford University Press (Revised Edition) Sontag, Susan, 1967: ‘Persona’. Sight and Sound 36(4): 186-92 Stabiner, Karen, 1977: ‘Altman has a dream and films it’. Mother Jones Magazine (February-March, 1977): 57-60 Thompson, David, 2006: Altman on Altman. London: Faber & Faber Thomson, David, 2010: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. London: Hachette (Fifth Edition) Warren, Charles, 2013: ‘ALTMAN, Robert’. In: Justin, Wintle (ed), 2013: New Makers of American Culture, Volume 1. London: Routledge: 26-8 Wood, Robin, 2003: Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan… and Beyond. Columbia University Press (Revised Edition)

|

|||||

|