|

|

Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (The)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th July 2015). |

|

The Film

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (W D Richter, 1984) The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (W D Richter, 1984)

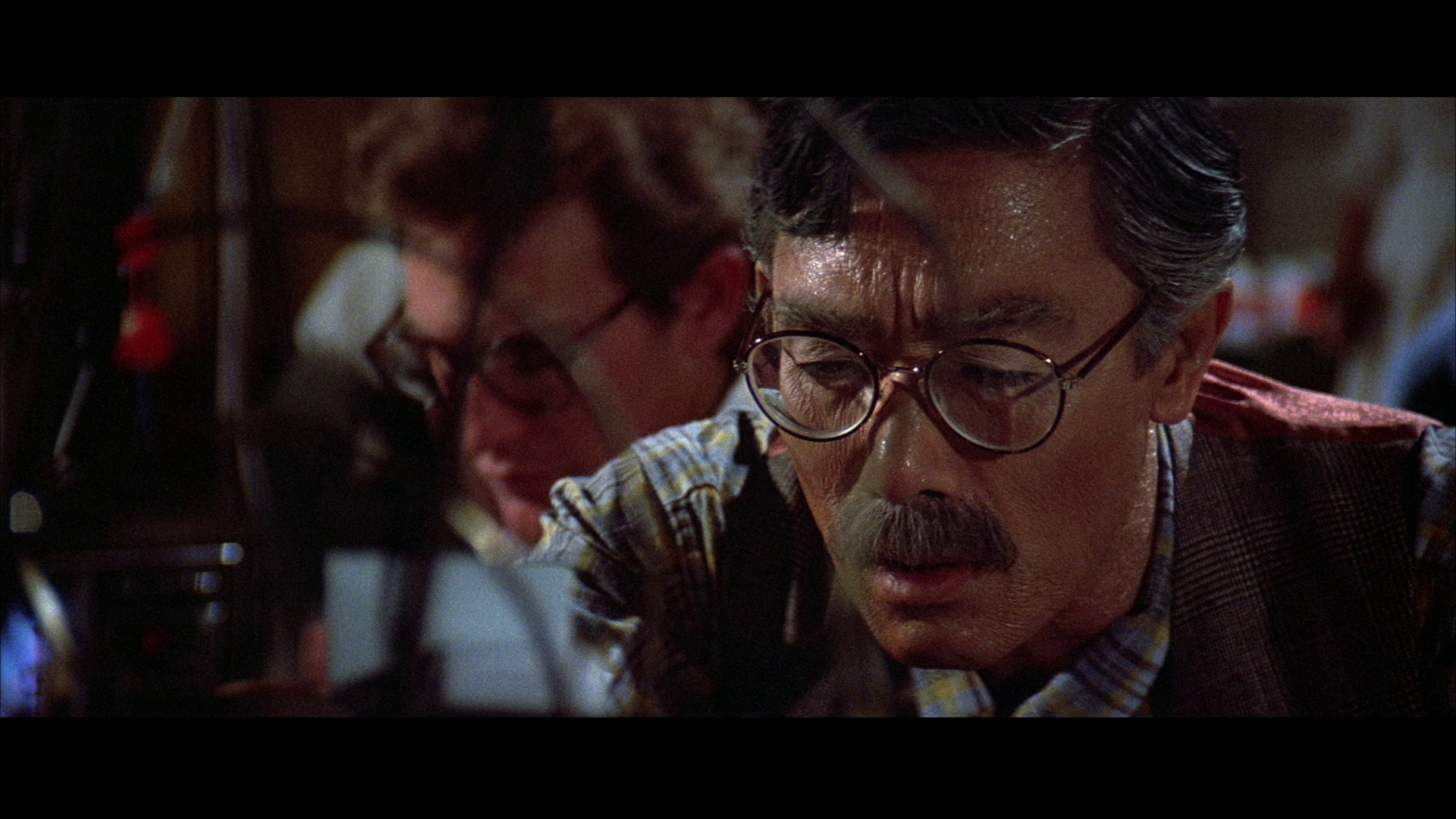

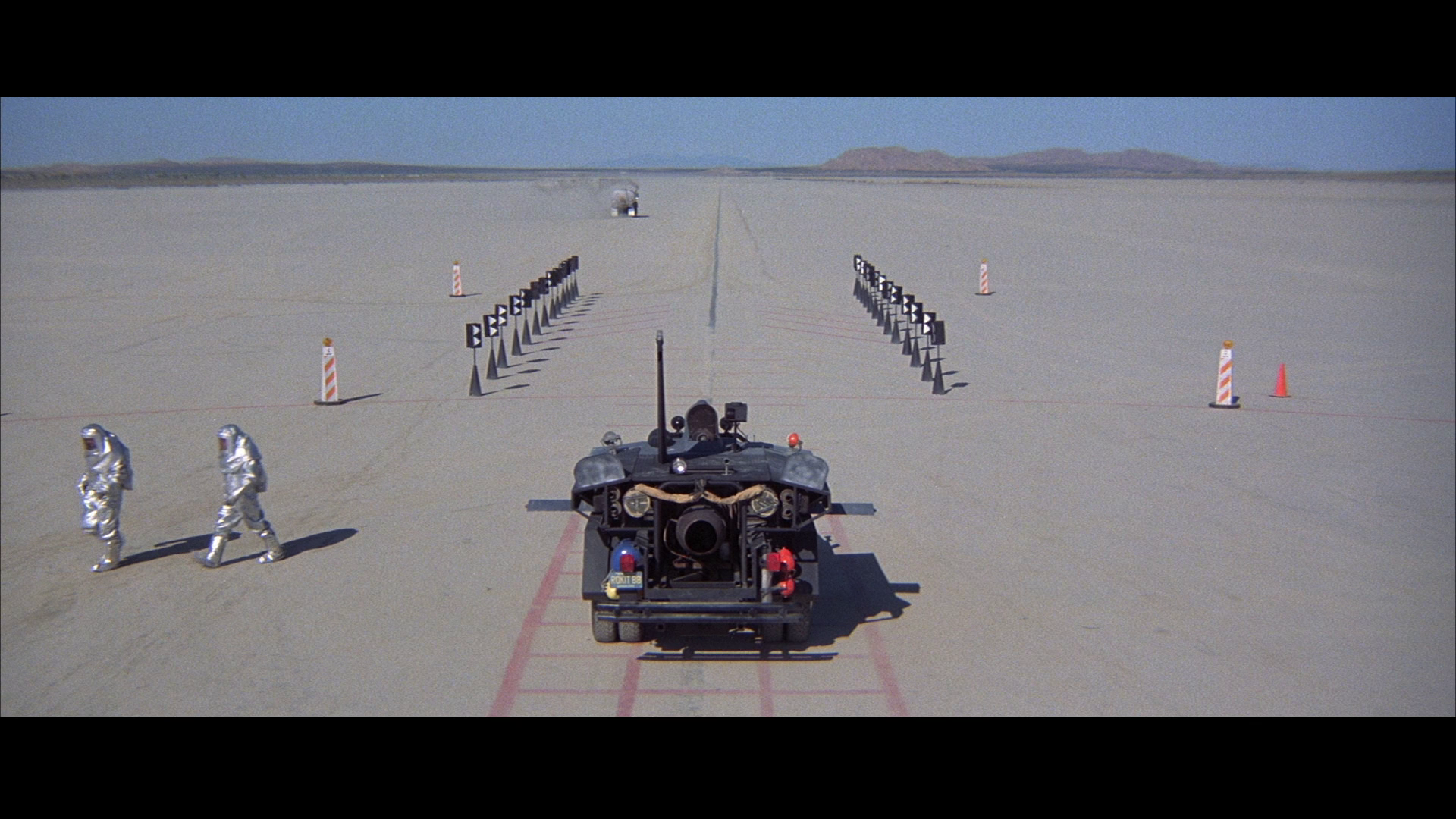

Films about true renaissance men are rare. (We can probably discount Penny Marshall’s Danny DeVito-starring 1994 picture Renaissance Man from the get-go.) W D Richter’s The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (1984), a film which struggled to find its audience in cinemas but became a cult favourite following its VHS release and innumerable television broadcasts, is an exception, focusing as it does on the titular Buckaroo Banzai (Peter Weller): ‘a brilliant neurosurgeon’, as the scrolling title that opens the film tells us, who became bored with his medical career and ‘roamed the planet studying martial arts and particle physics’, drawing to him ‘those hard-rocking scientists, The Hong Kong Cavaliers’. The Hong Kong Cavaliers consist of Professor Hikita (Robert Ito), whose research into trans-dimensional travel Banzai has expanded upon; Perfect Tommy (Lewis Smith); Rawhide (Clancy Brown); and Reno Nevada (Pepe Serna). They are joined by Dr Sidney Zwibel, soon to be christened ‘New Jersey’ (Jeff Goldblum), who Banzai hires after they have performed brain surgery together. The Hong Kong Cavaliers are scientists, working out of the Banzai Institute, who double as a touring rock group. Banzai also has assistance from the Blue Blazer Regulars: a Boy Scout-type group who worship Banzai.  Banzai and his group have developed a jet car that is powered by an ‘oscillating overthruster’. During testing of the jet car, Banzai pushes it to its limit, driving through a mountain and, in doing so, entering into another dimension (the eighth dimension of the film’s title). Whilst in this alternate dimension, Banzai witnesses bizarre creatures hurtling towards the jet car; and as evidence of this encounter, Banzai unwittingly brings back a part of one of these organisms, which has become attached to the chassis of the vehicle. Banzai and his group have developed a jet car that is powered by an ‘oscillating overthruster’. During testing of the jet car, Banzai pushes it to its limit, driving through a mountain and, in doing so, entering into another dimension (the eighth dimension of the film’s title). Whilst in this alternate dimension, Banzai witnesses bizarre creatures hurtling towards the jet car; and as evidence of this encounter, Banzai unwittingly brings back a part of one of these organisms, which has become attached to the chassis of the vehicle.

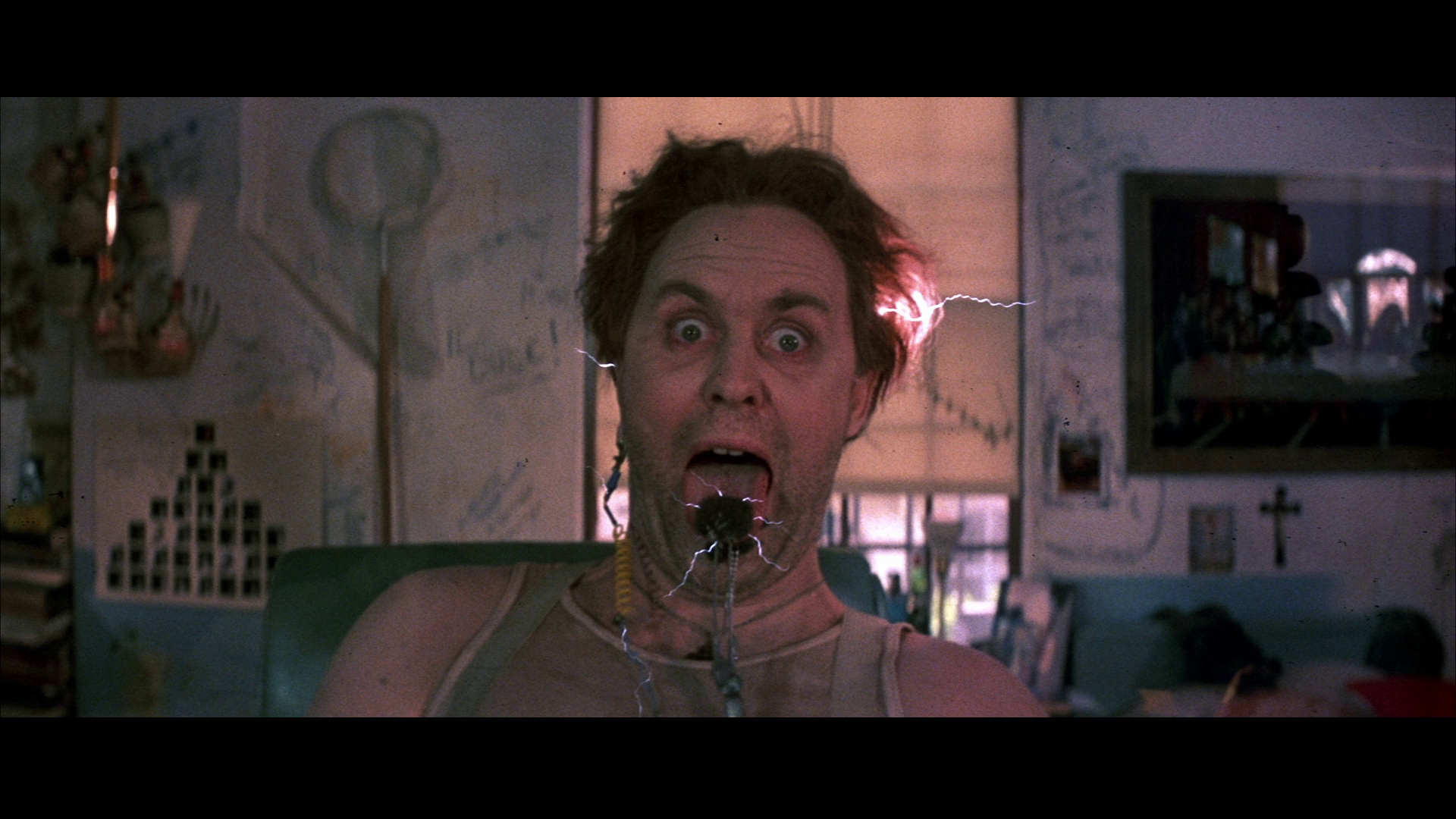

Later, whilst performing a gig (during which Banzai demonstrates his skill with a number of musical instruments) at Artie’s Artery, a nightclub in New Jersey, Banzai locks eyes with a female audience member, Penny Priddy (Ellen Barkin). Penny, it turns out, was orphaned at an early age, and Banzai deduces that she is the twin sister of his deceased wife. Like New Jersey, Penny is enlisted into Banzai’s group. Meanwhile, Dr Emilio Lizardo (John Lithgow) escapes from the Trenton Home for the Criminally Insane. In the 1930s, Lizardo – working with Hikita – experimented in the development of his own oscillating overthruster. Lizardo’s experiment was however a disaster, leaving Lizardo temporarily trapped between dimensions, penetrating a steel wall and becoming trapped in it – with the outcome being that Lizardo became diagnosed as utterly unstable, hence his incarceration in the mental institution from which he has escaped.  However, during that incident Lizardo became ‘possessed’ by an alien, belonging to the race of Red Lectroids, named Lord John Whorfin. The Red Lectroids, it seems, were imprisoned in the eighth dimension after being held responsible for an act of genocide committed on their home planet, Planet Ten. Placed in captivity by the Black Lectroids, the Red Lectroids escaped from the eighth dimension when Lizardo briefly broke into it, his experiment apparently offering a temporary portal for many of the Red Lectroids to pass through onto Earth. Since then, the Red Lectroids have lived in New Jersey, all of them taking the first name of ‘John’. Lizardo/Whorfin plans to steal Banzai’s oscillating overthruster to enable him, and his fellow Red Lectroids, to return to Planet Ten and seize control of it from the Black Lectroids who live peacefully there. The Black Lectroids have other ideas, and they contact Banzai, demanding that he eliminated Lord John Whorfin – or else they will fire a particle beam at the USSR, which would be perceived as a nuclear attack by the US, thus setting into motion the Cold War policy of ‘mutually assured destruction’. (‘That’s an action that the Kremlin will almost certainly misinterpret as an American first strike. They’re already a little trigger-happy as it us’, Perfect Tommy says when he finds out about this threat.) However, during that incident Lizardo became ‘possessed’ by an alien, belonging to the race of Red Lectroids, named Lord John Whorfin. The Red Lectroids, it seems, were imprisoned in the eighth dimension after being held responsible for an act of genocide committed on their home planet, Planet Ten. Placed in captivity by the Black Lectroids, the Red Lectroids escaped from the eighth dimension when Lizardo briefly broke into it, his experiment apparently offering a temporary portal for many of the Red Lectroids to pass through onto Earth. Since then, the Red Lectroids have lived in New Jersey, all of them taking the first name of ‘John’. Lizardo/Whorfin plans to steal Banzai’s oscillating overthruster to enable him, and his fellow Red Lectroids, to return to Planet Ten and seize control of it from the Black Lectroids who live peacefully there. The Black Lectroids have other ideas, and they contact Banzai, demanding that he eliminated Lord John Whorfin – or else they will fire a particle beam at the USSR, which would be perceived as a nuclear attack by the US, thus setting into motion the Cold War policy of ‘mutually assured destruction’. (‘That’s an action that the Kremlin will almost certainly misinterpret as an American first strike. They’re already a little trigger-happy as it us’, Perfect Tommy says when he finds out about this threat.)

At a press conference covering Banzai’s jet car and the trans-dimensional travel facilitated by the oscillating overthruster, Banzai is introduced by the Secretary of Defense (Matt Clark) as ‘a young man who yesterday took our notions of reality and turned them inside out’. Banzai explains to the audience the principle behind his oscillating overthruster, telling the listeners that the research was driven by ‘the possibility of contacting alien life. However, not on another planet, but here, maybe right inside this table, living on a simultaneous plane of existence with our own’. The experiment developed from Lizardo and Hikita’s work in the 1930s, which was based on the premise ‘that if solid matter is mostly just empty space, a person should be able to discover a way to travel inside things’. The oscillating overthruster does this by ‘systematically reorder[ing] matter by annihilating electrons, positrons…’  Banzai’s speech is interrupted by a soldier, who tells him ‘The President is calling’. ‘The president of what?’, Banzai queries. ‘The President of the United States’, is the reply he receives. ‘Oh’, Banzai declares, nonplussed. Banzai leaves the press conference to take the telephone call, which comes from the Black Lectroid ship that is orbiting Earth, and receives a shock to his ear. Returning to the room in which the press conference is being held, Banzai sees for the first time the Red Lectroids: the camera reveals two of them seated amongst the audience, the shock of the moment emphasised through the use of a reverse zoom dolly, as Banzai declares, ‘There they are! Don’t you see them? [….] Evil, pure and simple, from the eighth dimension’. Banzai later explains that he has been ‘ionised’ by the shock he received from the telephone call: the doors of perception have, for him, been cleansed and he is able to see the true form of the Red Lectroids who have been masquerading as humans – much as the sunglasses in John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) allow Nada (Roddy Piper) to identify the aliens that walk amongst the general population (‘You? you’re okay. This one? Real fucking ugly’, Nada declares in reference to a human standing next to an extraterrestrial). Banzai’s speech is interrupted by a soldier, who tells him ‘The President is calling’. ‘The president of what?’, Banzai queries. ‘The President of the United States’, is the reply he receives. ‘Oh’, Banzai declares, nonplussed. Banzai leaves the press conference to take the telephone call, which comes from the Black Lectroid ship that is orbiting Earth, and receives a shock to his ear. Returning to the room in which the press conference is being held, Banzai sees for the first time the Red Lectroids: the camera reveals two of them seated amongst the audience, the shock of the moment emphasised through the use of a reverse zoom dolly, as Banzai declares, ‘There they are! Don’t you see them? [….] Evil, pure and simple, from the eighth dimension’. Banzai later explains that he has been ‘ionised’ by the shock he received from the telephone call: the doors of perception have, for him, been cleansed and he is able to see the true form of the Red Lectroids who have been masquerading as humans – much as the sunglasses in John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) allow Nada (Roddy Piper) to identify the aliens that walk amongst the general population (‘You? you’re okay. This one? Real fucking ugly’, Nada declares in reference to a human standing next to an extraterrestrial).

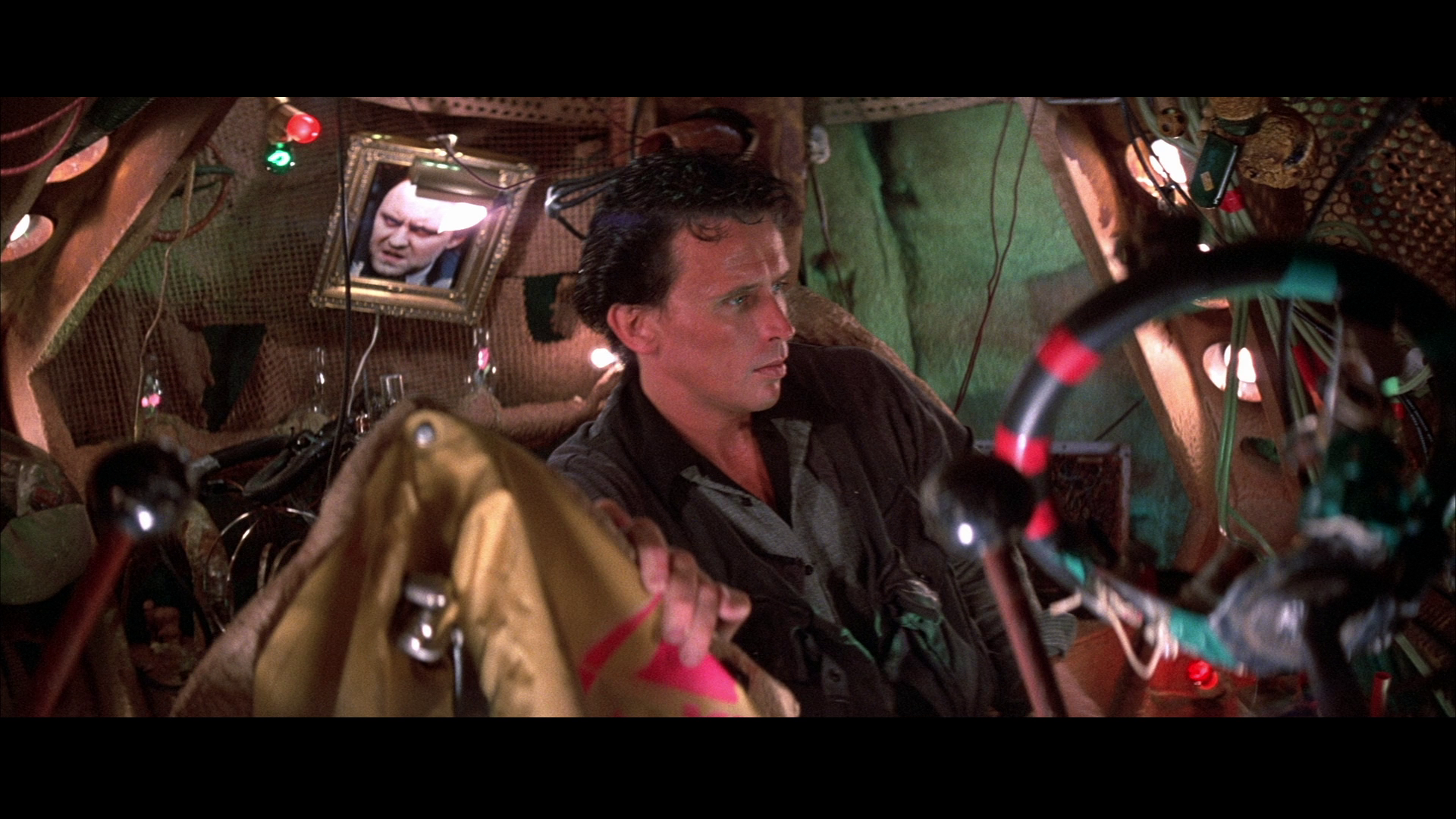

After Banzai has been ‘ionised’ and is able to see the reptilian lectroids for what they are, the film sources much humour from his assertions, delivered in typical deadpan form by Peter Weller, which become increasingly bizarre but are, given the nature and reputation of the Buckaroo Banzai character, taken deadly seriously by the other characters. Banzai’s assertions, delivered under the influence of whatever the aliens have administered to him (described by Banzai as ‘some electrochemical message that allows me to see what they really are’), sound increasingly like the paranoid ramblings of a conspiracy theorist but the other characters, who are unable to see through the human disguises of the Lectroids, place their trust in Banzai’s reputation. When Banzai talks via video call with President Widmark (Ronald Lacey) and the Secretary of Defense, McKinley (Matt Clark), McKinley declares, ‘Well, if it wasn’t Buckaroo Banzai, I’d say commit the man’. Banzai’s declarations begin with the shout of ‘Don’t you see them? [….] Evil, pure and simple, from the eighth dimension’, delivered when Banzai returns to the room in which the press conference is being held – which results in an initially bemused look from Rawhide and New Jersey, until the Red Lectroids flee from the room, an action which is taken as an index of their guilt. Shortly after, Banzai rescues Hikita, who has been taken captive by the Red Lectroids, telling his old friend that ‘I’ve been ionised [….] Aliens from the eighth dimension; I’m seeing them now’. Banzai then looks at the palm of his hand, claiming to ‘have a formula, an antidote of some kind’ that is written there invisibly: ‘Whoever it was with that phony call from the President gave me information and some electrochemical message that allows me to see what they really are’. ‘What are they?’, Hikita asks. ‘Lectroids from Planet Ten, by way of the eighth dimension’, Banzai replies with utter seriousness. The humour comes from the fact that these lunatic assertions, delivered in Weller’s characteristically deadpan way, are received with utter seriousness by the other characters.  When Banzai informs President Widmark and the Secretary of Defense of the Red Lectroid plot, the Secretary of Defense initially believes that Banzai is talking abut foreign nationals, thus interpreting Banzai’s words within his own xenophobic framework. The sequence begins with the Secretary of Defense suggesting to the President (comically strapped into a machine that’s intended to alleviate his back pain) that the US government should seize Banzai’s jet car, even if the Banzai Institute won’t sell it to them. ‘It’s not Buckaroo Banzai per se, Mr President’, the Secretary of Defense begins, ‘It’s his men. Foreigners, some of ‘em, or their names have been changed; their true backgrounds are shrouded in secrecy’. This discussion is interrupted, and Banzai connects with the President via a video call, telling him that ‘vicious aliens [are] walking among us’ and informing the President that the Red Lectroids are continuing their research under the umbrella of the New Jersey-based company Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems. Yoyodyne, it seems, has been given the contract for developing the US government’s new Truncheon Bomber. ‘In the hands of foreign nationals?’, the Secretary of Defense declares angrily, misinterpreting Banzai’s discussion of ‘aliens’. The President struggles to understand Banzai’s words too: when Banzai tells him of the conflict between the evil Red Lectroids and the more benign Black Lectroids, the President asks, ‘What are you saying, man? Some kind of race war in New Jersey’. To this, Banzai highlights the presence of John Parker, who is sitting beside him, telling the President that ‘This man, as you call him, is not a human being at all but is in face a Black Lectroid named John Parker from Planet Ten, and his spaceship is anchored above Yoyodyne’. When Banzai informs President Widmark and the Secretary of Defense of the Red Lectroid plot, the Secretary of Defense initially believes that Banzai is talking abut foreign nationals, thus interpreting Banzai’s words within his own xenophobic framework. The sequence begins with the Secretary of Defense suggesting to the President (comically strapped into a machine that’s intended to alleviate his back pain) that the US government should seize Banzai’s jet car, even if the Banzai Institute won’t sell it to them. ‘It’s not Buckaroo Banzai per se, Mr President’, the Secretary of Defense begins, ‘It’s his men. Foreigners, some of ‘em, or their names have been changed; their true backgrounds are shrouded in secrecy’. This discussion is interrupted, and Banzai connects with the President via a video call, telling him that ‘vicious aliens [are] walking among us’ and informing the President that the Red Lectroids are continuing their research under the umbrella of the New Jersey-based company Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems. Yoyodyne, it seems, has been given the contract for developing the US government’s new Truncheon Bomber. ‘In the hands of foreign nationals?’, the Secretary of Defense declares angrily, misinterpreting Banzai’s discussion of ‘aliens’. The President struggles to understand Banzai’s words too: when Banzai tells him of the conflict between the evil Red Lectroids and the more benign Black Lectroids, the President asks, ‘What are you saying, man? Some kind of race war in New Jersey’. To this, Banzai highlights the presence of John Parker, who is sitting beside him, telling the President that ‘This man, as you call him, is not a human being at all but is in face a Black Lectroid named John Parker from Planet Ten, and his spaceship is anchored above Yoyodyne’.

The irony is that whilst Banzai’s assertions are taken at face value, Lizardo’s similarly bizarre ramblings are dismissed by the characters around him. Although both men are scientists, the difference between them (other than the fact that Lizardo is ‘possessed’ by the Red Lectroid John Whorfin), is that Lizardo has been committed to the Trenton Home for the Criminally Insane after attacking the other members of his research team during the 1930s. (Oddly, nobody within the film appears to have noticed that Lizardo seems not to have aged since that time.) When, as a preface to his escape, Lizardo tells the nurse who attends to him that ‘I’m going home with my overthruster’, his statement provokes laughter from the nurse who, sarcastically, tells Lizardo ‘I’ll make sure you get an early wakeup call’.  Banzai’s associates have to be as capable with an electric guitar as with an electron microscope. In the opening sequence, Banzai is shown to be late for the testing of his jet car, powered by the oscillating overthruster, because he is performing brain surgery. Banzai is using a laser to burn out a tumour in the pineal gland of a patient. Turning towards the male doctor who is assisting in this delicate operation, Banzai asks, ‘You ever thought about joining me full time? [….] Can you sing?’ The doctor is New Jersey; shortly after, Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers pick up New Jersey in their bus, the new recruit bizarrely dressed like John Wayne in The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), complete with bright red ‘bib’ shirt. Although New Jersey is given relatively little to do as part of Banzai’s team, he delivers one of the film’s most memorable speeches, spoken by Goldblum with the same deadpan sobriety as Weller’s declarations as Banzai. In this speech, New Jersey suggests to Perfect Tommy that Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds’ radio broadcast in 1938 may not have been a hoax but may instead have been a truthful reportage of the Red Lectroid’s escape from the eighth dimension and their appearance in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey: ‘There was a huge electrical dimensional accident, some giant explosion’, New Jersey suggests, ‘And they hypnotised Orson Welles into covering it up – so first he says there’s an invasion from Mars, but then he says “No, no, no; it’s just a radio show hoax”. Get it?’ Banzai’s associates have to be as capable with an electric guitar as with an electron microscope. In the opening sequence, Banzai is shown to be late for the testing of his jet car, powered by the oscillating overthruster, because he is performing brain surgery. Banzai is using a laser to burn out a tumour in the pineal gland of a patient. Turning towards the male doctor who is assisting in this delicate operation, Banzai asks, ‘You ever thought about joining me full time? [….] Can you sing?’ The doctor is New Jersey; shortly after, Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers pick up New Jersey in their bus, the new recruit bizarrely dressed like John Wayne in The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), complete with bright red ‘bib’ shirt. Although New Jersey is given relatively little to do as part of Banzai’s team, he delivers one of the film’s most memorable speeches, spoken by Goldblum with the same deadpan sobriety as Weller’s declarations as Banzai. In this speech, New Jersey suggests to Perfect Tommy that Orson Welles’ ‘War of the Worlds’ radio broadcast in 1938 may not have been a hoax but may instead have been a truthful reportage of the Red Lectroid’s escape from the eighth dimension and their appearance in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey: ‘There was a huge electrical dimensional accident, some giant explosion’, New Jersey suggests, ‘And they hypnotised Orson Welles into covering it up – so first he says there’s an invasion from Mars, but then he says “No, no, no; it’s just a radio show hoax”. Get it?’

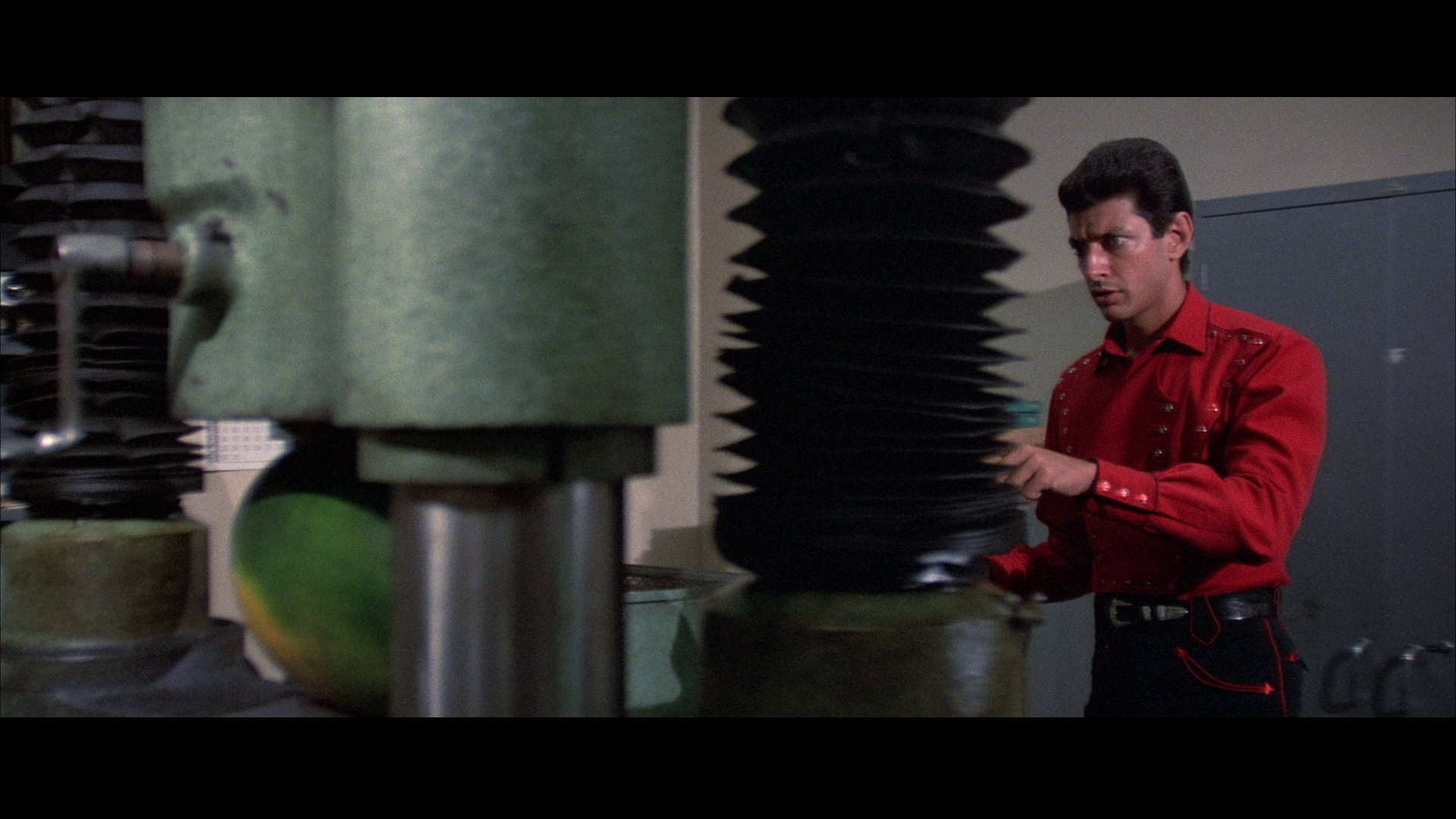

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai was one of a number of highly postmodern science-fiction films made during the 1980s: the tension within American science-fiction cinema of that era seemed to be between SF pictures that offered a knowing pastiche of films noir (for example, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, 1982; and Charles Band’s Trancers, 1984) in order to make the ‘alien’ (eg, the future) seem familiar, and the more anarchic SF films driven by a punk ethos (for example, Alex Cox’s Repo Man, 1984) which sought to make the familiar (eg, the reality of contemporary existence) seem ‘alien’. Amongst the latter group of films, arguably, are those which attempt to create a sense of cognitive dissonance in the viewer by suggesting that aliens walk among us, in human disguise. This idea can, of course, be traced back to examples of SF literature such as John W Campbell’s 1938 novella Who Goes There?, Robert Heinlein’s 1951 novel The Puppetmasters and Jack Finney’s 1954 book The Body Snatchers. However, during the 1980s, a number of films focusing on aliens who masquerade as humans seemed to be produced alongside films, such as Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), which focused on the human body being ‘contaminated’ or ‘polluted’ by aliens from within. John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing, based on Who Goes There?, arguably highlights the relationships between both of these groups of films, with its focus on alien contamination of humans by alien cells which absorb and then replicate human cells. Other films, such as Jach Sholder’s The Hidden (1987) feature alien species which in effect ‘possess’ their hosts along the lines of the parasites in David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975). (The Hidden’s approach to this theme is similar to that of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, as the film suggests that John Whorfin has somehow inhabited the body of Emilio Lizardo – though the other Red Lectroids seem simply to be disguised as humans.) However, a number of other films depict aliens living amongst humans ‘in disguise’, the films’ human protagonists discovering ways to overcome these disguises and reveal the true nature of these alien visitors: Kenneth Johnson’s miniseries V (NBC, 1983) – with its sequels V: The Final Battle (NBC, 1984) and the series V (NBC, 1984-5) – and John Carpenter’s They Live, along with The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, are key examples of this trend. All of these represent the visiting extraterrestrials as reptilian creatures, prefiguring David Icke’s ‘lizard people’ conspiracy theories of the 1990s – though that itself can be traced to the work of Robert E Howard and H P Lovecraft in the early 20th Century.  Prior to The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, W D Richter had of course written Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which in some ways covers similar thematic territory (in terms of humans being ‘replaced’ by extraterrestrials), and had also contributed to the screenplay for Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China (1982). The Carpenter film shares its dry sense of humour with Buckaroo Banzai. One of Buckaroo Banzai’s most memorable gags is the moment in which, during the Red Lectroids’ assault on the Banzai Institute, Reno leads New Jersey through a laboratory filled with complicated-looking scientific equipment. ‘Why is there a watermelon there?’, a bemused New Jersey asks, drawing the viewers’ attention to the bizarre sight of a watermelon trapped in a pressure testing machine. ‘I’ll tell you later’, Reno says, and both of them get back to the business of routing out the attacking Lectroids. Defining Buckaroo Banzai’s off-kilter approach to comedy, it’s a moment that catches the viewer off-guard – taking place during quite a tense sequence in which the humans face off against their Red Lectroid enemies – and which is all the more amusing (and memorable) for the fact that there is no ‘punchline’: the watermelon is never discussed again. (W D Richter has since said, in the commentary for the film, that the incongruous moment with the watermelon was inserted into the film to test whether or not the studio executives were watching the rushes carefully.) Another equally humourous moment takes place when friendly Black Lectroid John Parker (Carl Lumbly), wearing a silver jacket and carrying a big pink parcel, rides on a bicycle up to the front gate of the Banzai Institute, and an offscreen voice shouts, ‘Hey, man, nice jacket! … What’s in the big pink box?’ Prior to The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, W D Richter had of course written Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which in some ways covers similar thematic territory (in terms of humans being ‘replaced’ by extraterrestrials), and had also contributed to the screenplay for Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China (1982). The Carpenter film shares its dry sense of humour with Buckaroo Banzai. One of Buckaroo Banzai’s most memorable gags is the moment in which, during the Red Lectroids’ assault on the Banzai Institute, Reno leads New Jersey through a laboratory filled with complicated-looking scientific equipment. ‘Why is there a watermelon there?’, a bemused New Jersey asks, drawing the viewers’ attention to the bizarre sight of a watermelon trapped in a pressure testing machine. ‘I’ll tell you later’, Reno says, and both of them get back to the business of routing out the attacking Lectroids. Defining Buckaroo Banzai’s off-kilter approach to comedy, it’s a moment that catches the viewer off-guard – taking place during quite a tense sequence in which the humans face off against their Red Lectroid enemies – and which is all the more amusing (and memorable) for the fact that there is no ‘punchline’: the watermelon is never discussed again. (W D Richter has since said, in the commentary for the film, that the incongruous moment with the watermelon was inserted into the film to test whether or not the studio executives were watching the rushes carefully.) Another equally humourous moment takes place when friendly Black Lectroid John Parker (Carl Lumbly), wearing a silver jacket and carrying a big pink parcel, rides on a bicycle up to the front gate of the Banzai Institute, and an offscreen voice shouts, ‘Hey, man, nice jacket! … What’s in the big pink box?’

In his introduction to John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981), when it was broadcast as part of the BBC’s Moviedrome series, Alex Cox asserted that although he believes Carpenter’s They Live to be ‘highly underrated’, it ‘falls down at the end, stumbling as do many modern science-fiction films into a dull welter of chases down corridors and high-tech gunfire – similar malaises afflict Total Recall and Terminator 2’ (Cox & Jones, 1993: 12). Like those other SF films of the era, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai climaxes with a series of chases, punctuated with gunfire and scattershot jokes, through narrow spaces in environments that speak of the corporate-industrial landscape of the period: the corridors of the Banzai Institute, and the various rooms within the Armco Steel Plant in Torrance, California (which was used as the location for the Red Lectroid’s base of operations). (Armco sadly closed in 1985, the year after the release of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai; the closing of the Armco plant marked the end of heavy manufacturing in the area.) In his introduction to John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981), when it was broadcast as part of the BBC’s Moviedrome series, Alex Cox asserted that although he believes Carpenter’s They Live to be ‘highly underrated’, it ‘falls down at the end, stumbling as do many modern science-fiction films into a dull welter of chases down corridors and high-tech gunfire – similar malaises afflict Total Recall and Terminator 2’ (Cox & Jones, 1993: 12). Like those other SF films of the era, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai climaxes with a series of chases, punctuated with gunfire and scattershot jokes, through narrow spaces in environments that speak of the corporate-industrial landscape of the period: the corridors of the Banzai Institute, and the various rooms within the Armco Steel Plant in Torrance, California (which was used as the location for the Red Lectroid’s base of operations). (Armco sadly closed in 1985, the year after the release of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai; the closing of the Armco plant marked the end of heavy manufacturing in the area.)

Like a number of other SF films of the era, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai returns the conflict between the human and its ‘other’ to the spaces associated with corrupt corporations and then-dying heavy industries. The climax of James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) takes place in the manufacturing plant of Cyberdyne, the company which, in the film’s sequels, will use the technology that is left from the destroyed Terminator to develop the Skynet system that will in the future invent them; the climax of Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) sees the human characters battling the newer T1000 in a similar industrial setting (a steelworks) after waging a war against Cyberdyne at its headquarters; similarly, Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987) sees the ‘rebuilt’ Murphy (played again by Peter Weller) battling Clarence Boddicker’s (Kurtwood Smith) criminal gang, bankrolled by the vice-president of Omni-Consumer Products Dick Jones (Ronny Cox), in a deserted steel mill (the Duquesne Steel Works) before returning to OCP’s boardroom to eliminate Jones. Like these films, in its climax The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai places corporate spaces in juxtaposition with landscapes that symbolise the death of tradition heavy industries, the film’s heroes pursuing the inhuman villains through these environments – foregrounding some of the economic changes (deindustrialisation) that were taking place during the era. The alien-owned and controlled Yoyodyne, with its private contract to build military hardware for the US government, is thus yet another corrupt corporation, like OCP in RoboCop, Cyberdyne in The Terminator, the Tyrell Corporation in Blade Runner and Weylan(d)-Yutani in Alien and its sequels. The film’s naming of this sinister corporation as Yoyodyne is an allusion to the defense contractor and aeronautics manufacturer, modeled on Boeing, that features in Thomas Pynchon’s novels V. (1964) and The Crying of Lot 49 (1966); subsequent to the release of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, Yoyodyne would appear as a fictional company in television series such as Star Trek: The Next Generation (CBS, 1987-94), where Yoyodyne was cited as the builder of starships and warp drive engines, and Angel (Fox, 1999-2004).  The studio struggled to market the completed The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, finding the film difficult to pigeon-hole. Richter’s original cut was shorn of its opening sequence (presented as home movie footage, this introduced us to Banzai’s parents and explained their deaths as a result of their experiments in trans-dimensional travel), replacing this with the Star Wars-style scrolling title mentioned above, and a handful of other brief moments. (This Blu-ray release presents these deleted scenes as ‘extras’, and also offers the option of viewing the film with the original ‘home movie’ opening sequence.) The film is presented here in the final studio cut of 102:35 mins. The studio struggled to market the completed The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, finding the film difficult to pigeon-hole. Richter’s original cut was shorn of its opening sequence (presented as home movie footage, this introduced us to Banzai’s parents and explained their deaths as a result of their experiments in trans-dimensional travel), replacing this with the Star Wars-style scrolling title mentioned above, and a handful of other brief moments. (This Blu-ray release presents these deleted scenes as ‘extras’, and also offers the option of viewing the film with the original ‘home movie’ opening sequence.) The film is presented here in the final studio cut of 102:35 mins.

Video

Presented here in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, this 1080p presentation of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Presented here in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, this 1080p presentation of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 28Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

The film has an excellent presentation here. The strong colour consistency is a notable difference between this HD presentation and earlier DVD releases. Excellent contrast levels handle the juxtaposition of the opening jet car launch in the bright sun of the desert and the dark interiors of the control rooms very well. There’s a very strong level of fine detail on display (eg, in facial close-ups), and a characteristically robust encode ensures that the film has the appearance of 35mm film, with a natural and organic level of film grain present throughout the picture. It’s a marvelous presentation of the film, a huge improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases.   NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

There are two audio options: a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 remix and a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. Both tracks evidence strong range. Purists will probably wish to stick with the two-channel LPCM track, which is rich and a little more forceful than the 5.1 remix: the 5.1 track demonstrates added separation but packs a little less ‘punch’. Nevertheless, both tracks are very good, and are accompanied by optional English HoH subtitles.

Extras

An extraordinary range of contextual material is present on the disc, including:  - an audio commentary with director W D Richter and writer Earl Mac Rauch. This commentary is lively, entertaining and informative. It has a jokey tone, with Richter and Rauch discussing the film as if it were a docudrama, Richter suggesting that they have been hired to talk about the film by the Banzai Institute and Rauch performing throughout as Reno, a member of the Banzai Institute. It’s the same commentary that has been included on previous DVD releases of the picture. - an audio commentary with director W D Richter and writer Earl Mac Rauch. This commentary is lively, entertaining and informative. It has a jokey tone, with Richter and Rauch discussing the film as if it were a docudrama, Richter suggesting that they have been hired to talk about the film by the Banzai Institute and Rauch performing throughout as Reno, a member of the Banzai Institute. It’s the same commentary that has been included on previous DVD releases of the picture.

- Deleted scenes. There are 14 deleted scenes in total, and the viewer may watch these individually or via a ‘Play All’ option (14:17). 1. ‘Back Stage’ (0:52). This scene features the Hong Kong Cavaliers analysing the organism that Banzai brought back with him from the eighth dimension. 2. ‘Penny’s Troubles’ (1:20). This is an extension of the scene set in Artie’s Artery in which a weeping Penny tells Banzai about the reasons for her upset. 3. ‘Conference’ (1:15). This is an extension of the press conference sequence. 4. ‘“Dr Lizardo?”’ (0:43). In this further extension of the press conference sequence, Banzai references, and dismisses, Lizardo’s work. 5. ‘“Give Me a Fix!”’ (0:37). In this scene, the Red Lectroids suck on a car battery, further developing a brief moment shown earlier in the film in which Whorfin plugs himself in to a television set – suggesting the Lectroids somehow thrive on electricity. 6. ‘A Little Down’ (0:33). The Hong Kong Cavaliers wait in the press conference for the return of Banzai, who has fled the room to rescue Hikita from the Red Lectroids. 7. ‘“Therma-What?”’ (0:23). The Red Lectroids discuss the Black Lectroid spacecraft that crashes on Earth. 8. ‘New Jersey’ (1:20). New Jersey is introduced to several members of the Banzai Institute. 9. ‘John Emdall’ (1:02). In this addition to the scene in which the leader of the Black Lectroids (Rosalind Cash) communicates with the Hong Kong Cavaliers, it is revealed that the communication is ‘live’ rather than a recording – as the Cavaliers initially believe. 10. ‘“Hanoi Xan?”’ (0:47). Banzai tells Penny about the death of his wife, Penny’s twin sister. 11. ‘Penny Confronts Lizardo’ (0:45). Penny confronts Lizardo, mistakenly believing him to be Hanoi Xan, the man responsible for the death of her twin sister (as revealed to Penny by Banzai in the previous deleted scene). 12. ‘“Solve These Equations!”’ (2:45). Lizardo interrogates Banzai further. 13. ‘A Piece of Cake’ (0:42). This is an extension of the action-oriented sequence in which the Hong Kong Cavaliers rescue Penny. 14. ‘Illegal Aliens’ (1:07). Reno suggests to Banzai that the remaining Red Lectroids should be imprisoned as illegal immigrants. - ‘The Tao of Buckaroo’ (16:35). In this new interview with Peter Weller, the actor – always a fascinating interviewee – discusses his transition from his musical background to the world of acting. Weller talks about working with Jeff Goldblum, with whom Weller apparently had a sextet for a while after making the film. He reflects on some of the people whose personality helped to shape his performance as Buckaroo Banzai: Elia Kazan, Adam Ant and Jacques Cousteau. For Weller, the film is a satire in which ‘the bad guys are redneck aliens; the good guys are Rasta aliens’. He claims that the film is ‘definitely an allegory’, and the last sentence ‘is the most self-effacing and Zen-like’ closing line ‘that I’ve ever seen in a movie: “So what? Big deal?”’ Weller also discusses the conflict that led to Jordan Cronenweth leaving the picture, owing to ‘the time that Jordan takes’, and being replaced with Fred J Koenekamp – whose photography was more ‘journeyman’, Weller suggests. Weller also talks about his work as a lecturer, suggesting that in his classes about film, ‘just like art, some of it will be laughed away, and – thank God – certain smart dudes will think, “Nah, we gotta look at Buckaroo Banzai again, you know? Why? Because nobody understands what the hell it is? If for nothing else we gotta look at Buckaroo, because we don’t understand what this movie’s about”’. - ‘Lord John’ (13:39). This is another new interview, this time with John Lithgow. Lithgow discusses his approach to playing ‘bad guys’ – and the difficulties he faced in playing a character with a dual identity (Lizardo/Whorfin). Lithgow suggests that for his final speech to the Red Lectroids, he ‘looked at footage of Mussolini himself’ for inspiration. ‘We knew that the more seriously we took it, the more funny it was’, Lithgow says; and he suggests that shooting the film was the most fun he had on set other than making Third Rock from the Sun. (Lithgow also points to a brief moment from the film in which he demonstrates the phenomenon of ‘corpsing’.) - ‘Buckaroo Banzai Declassified’ (22:51). This featurette, which has appeared on the film’s previous DVD releases, focuses on the production of the film and contains vintage interviews with Weller, Richter, Lithgow, Barkin, and several other actors who featured in the film. In a new – at the time of the production of the featurette – interview with Richter, the fllm’s director discusses Banzai as if he were a real person, producing ‘evidence’ of Banzai’s adventures in the form of props, etc. - Lincoln Center Q&A (43:27). Recorded in 2011, this is a Q&A session with Weller and Lithgow, hosted by Kevin Smith, that took place after a screening of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai during the 48th New York Film Festival. - Visual essay by Matt Zoller Seitz (18:08). In this new, snazzily-edited video essay, film/television critic and filmmaker Seitz discusses his ideas about The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, exploring the film’s relationship with its cultural context and its association with other films, such as the 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers remake. Seitz also talks about the film’s cast and explores elements of their performances within the film. - Alternate opening (7:14). This alternate opening for the film is presented as a home movie and explores Banzai’s childhood and the deaths of his parents. The viewer is presented with the option of watching the film with this alternate opening in place. - Textless closing sequence (4:03). This presents the viewer with the option of watching the iconic closing titles sequence sans the titles that accompany it in the film. - Teaser trailer (1:17). - ‘Jet Car Concept’ (2:26). This is the short computer-generated promo piece, made in 1998, for the proposed Buckaroo Banzai television series Ancient Secrets and New Mysteries – which never came to fruition. - Gallery (2:46). - ‘Banzai Radio’ (10:02). Here, a former unit publicist for Fox, Terry Erdmann, is interviewed about the film’s marketing campaign and how audiences responded to it. This interview has appeared on previous DVD releases of the picture.

Packaging

Retail copies include reversible artwork and a lavishly illustrated booklet that includes new writing about the film by critic James Oliver.

Overall

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai opens with a long title scrawl that, like that of Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), scrolls upwards. This scrawl tells us that ‘Buckaroo Banzai, born to an American mother and a Japanese father, thus began life as he was destined to live it… going in several directions at once’. The same is true of the film, which mixes Hollywood genres at a rate of knots – thus seemingly proving the conclusion reached by W D Richter’s insertion of the gag about the watermelon, that the studio executives weren’t paying close attention to the rushes, to be correct. The film’s scattershot approach to the material is one of its charms, underpinned by Weller’s deadpan delivery of some utterly bizarre lines relating to Banzai’s newfound awareness of the presence of the Black and Red Lectroids on Earth. Banzai’s wisdom is wrapped up in his quoting of Confucius (‘Remember, no matter where you go, there you are’). Allusions to popular culture come thick and fast within the script, and the humour oscillates from the middlebrow to the obvious (John Whorfin continually mispronouncing John Bigbooté’s surname as ‘big booty’). In terms of its depiction of corporate villains and the juxtaposition of the spaces associated with corporations with locations symbolic of the dying heavy industries, the film taps into the zeitgeist of 1980s science-fiction; this is also evident in the jerry-rigged jet car that is capable of trans-dimensional travel, which seems to come from the same vein of thought that devised the timetraveling DeLorean – with all that it symbolises about the American motor industry – that features in the next year’s Back to the Future (Robert Zemeckis, 1985). The oft-repeated suggestion that the narrative is too complicated is fallacious: the film’s storyline makes perfect sense… mostly. However, Some viewers may find the film ‘too cool for school’; but if you’re on its wavelength, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai is an utter delight. The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai opens with a long title scrawl that, like that of Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), scrolls upwards. This scrawl tells us that ‘Buckaroo Banzai, born to an American mother and a Japanese father, thus began life as he was destined to live it… going in several directions at once’. The same is true of the film, which mixes Hollywood genres at a rate of knots – thus seemingly proving the conclusion reached by W D Richter’s insertion of the gag about the watermelon, that the studio executives weren’t paying close attention to the rushes, to be correct. The film’s scattershot approach to the material is one of its charms, underpinned by Weller’s deadpan delivery of some utterly bizarre lines relating to Banzai’s newfound awareness of the presence of the Black and Red Lectroids on Earth. Banzai’s wisdom is wrapped up in his quoting of Confucius (‘Remember, no matter where you go, there you are’). Allusions to popular culture come thick and fast within the script, and the humour oscillates from the middlebrow to the obvious (John Whorfin continually mispronouncing John Bigbooté’s surname as ‘big booty’). In terms of its depiction of corporate villains and the juxtaposition of the spaces associated with corporations with locations symbolic of the dying heavy industries, the film taps into the zeitgeist of 1980s science-fiction; this is also evident in the jerry-rigged jet car that is capable of trans-dimensional travel, which seems to come from the same vein of thought that devised the timetraveling DeLorean – with all that it symbolises about the American motor industry – that features in the next year’s Back to the Future (Robert Zemeckis, 1985). The oft-repeated suggestion that the narrative is too complicated is fallacious: the film’s storyline makes perfect sense… mostly. However, Some viewers may find the film ‘too cool for school’; but if you’re on its wavelength, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai is an utter delight.

This Blu-ray release contains a highly impressive presentation of the film and an exhaustive array of contextual material; as such, it should prove to be an essential purchase to viewers who are on the film’s wavelength… Now, what’s that watermelon doing here? References: Cox, Alex & Jones, Nick, 1993: Moviedrome: The Guide 2. London: BBC

|

|||||

|