|

|

Quatermass AKA The Quatermass Conclusion (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd July 2015). |

|

The Show

Quatermass (Piers Haggard, 1979) Quatermass (Piers Haggard, 1979)

With this series, John Mills joined the ranks of the number of actors who have played Nigel Kneale’s character of Professor Bernard Quatermass in television and cinema: on television the character had been played by Reginald Tate in the original 1953 BBC production of The Quatermass Experiment, John Robinson in its sequel series Quatermass II (BBC, 1955), and Andre Morell in Quatermass and the Pit (BBC, 1958-9). These actors were joined on the big screen by Brian Donlevy, whose performance as an American Quatermass featured in the film adaptations of the first two serials, The Quatermass Xperiment (Val Guest, 1955) and Quatermass 2 (Val Guest, 1957), and Andrew Keir in Quatermass and the Pit (Roy Ward Baker, 1967). (Since Quatermass, the character has also been played by Jason Flemyng in the BBC’s 2005 remake of The Quatermass Experiment.) John Mills was the first actor to play Quatermass on both the big and small screens – but in contrast with prior Quatermass film adaptations, which were separate productions from the television versions, this final Quatermass serial was broadcast in four parts on UK television and released to cinemas in America (as The Quatermass Conclusion) in a version edited to feature film length. Within its four episodes, Quatermass revisits and consolidates some of the themes of Kneale’s earlier Quatermass serials, including The Quatermass Experiment’s focus on the space race, and Quatermass and the Pit’s examination of the relationships between science and the occult.  Episode one, ‘Ringstone Round’, opens with Professor Bernard Quatermass being dumped unceremoniously by a London cab driver in the middle of the city. The cab driver refuses to venture closer to Quatermass’ destination, the studios of British Television (BTV), owing to fears of attacks by one or the other of the two youth gangs who terrorise the streets, the Badders and the Blue Brigade. Quatermass decides to walk the rest of the way. He is shocked to hear gunfire in the streets, and he is accosted by members of one of the street gangs but rescued by Joe Kapp (Simon MacCorkindale). Luckily, Kapp – a fellow scientist – is also heading to the television studio, to appear on the same programme as Quatermass. Episode one, ‘Ringstone Round’, opens with Professor Bernard Quatermass being dumped unceremoniously by a London cab driver in the middle of the city. The cab driver refuses to venture closer to Quatermass’ destination, the studios of British Television (BTV), owing to fears of attacks by one or the other of the two youth gangs who terrorise the streets, the Badders and the Blue Brigade. Quatermass decides to walk the rest of the way. He is shocked to hear gunfire in the streets, and he is accosted by members of one of the street gangs but rescued by Joe Kapp (Simon MacCorkindale). Luckily, Kapp – a fellow scientist – is also heading to the television studio, to appear on the same programme as Quatermass.

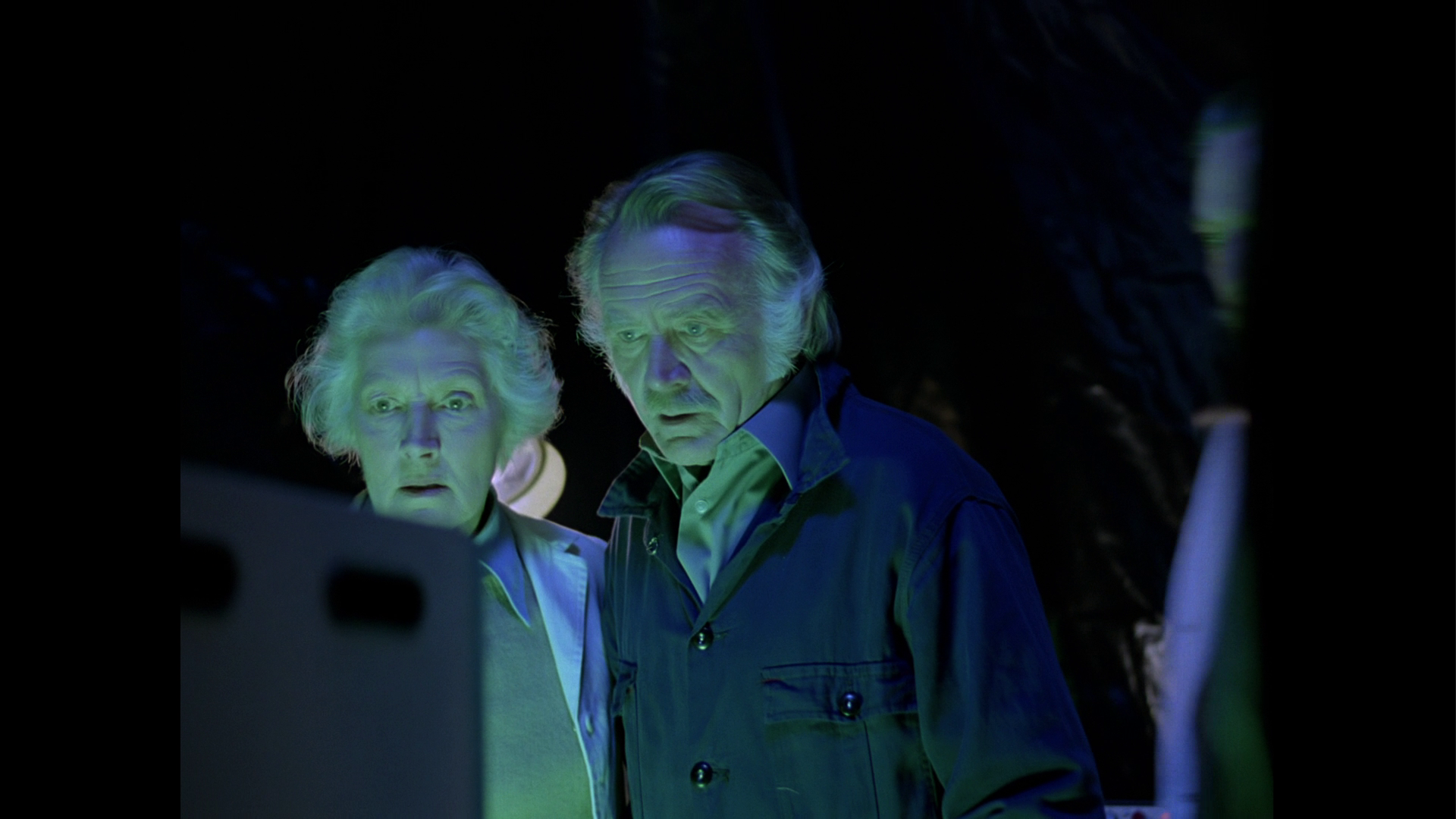

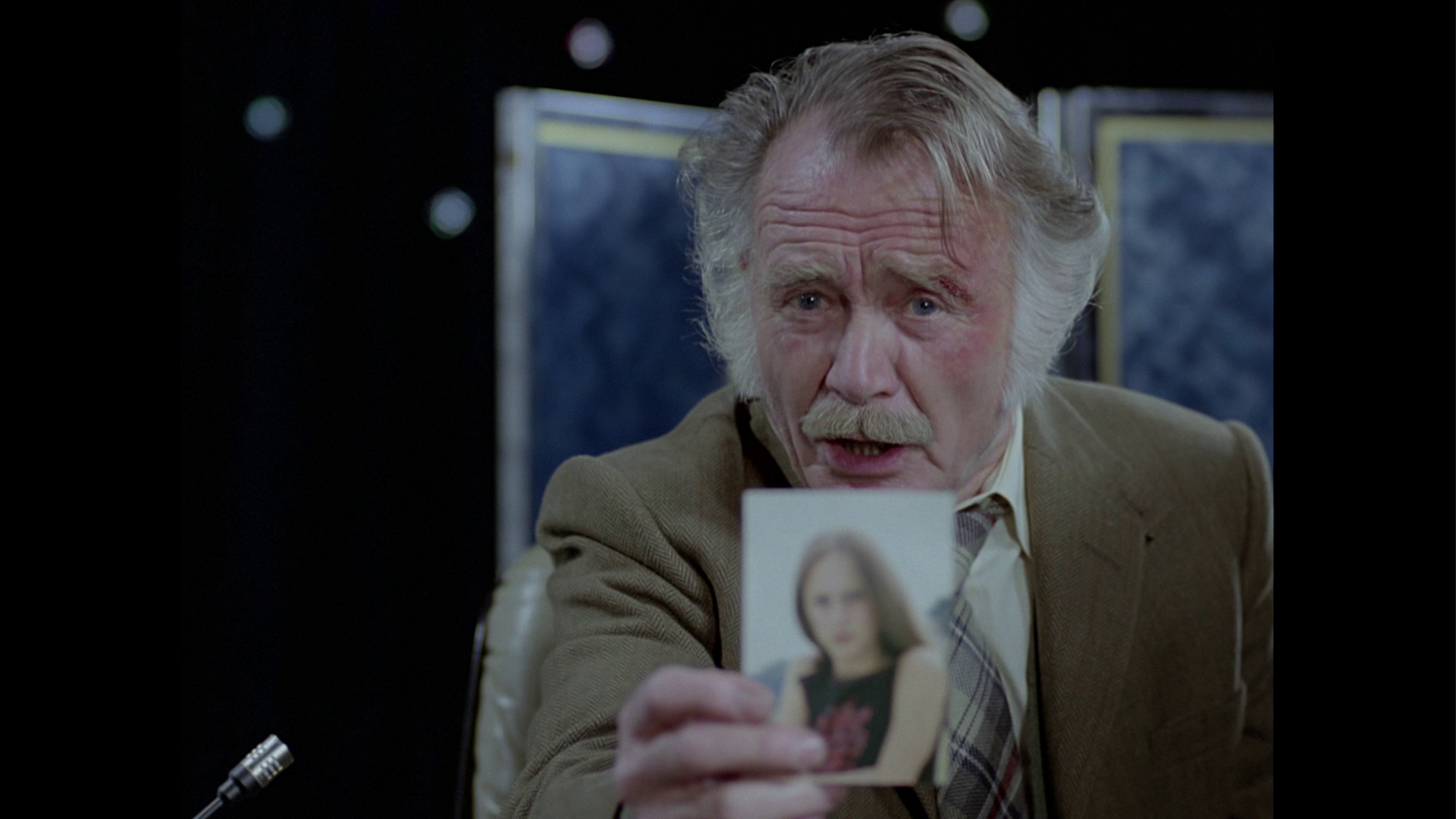

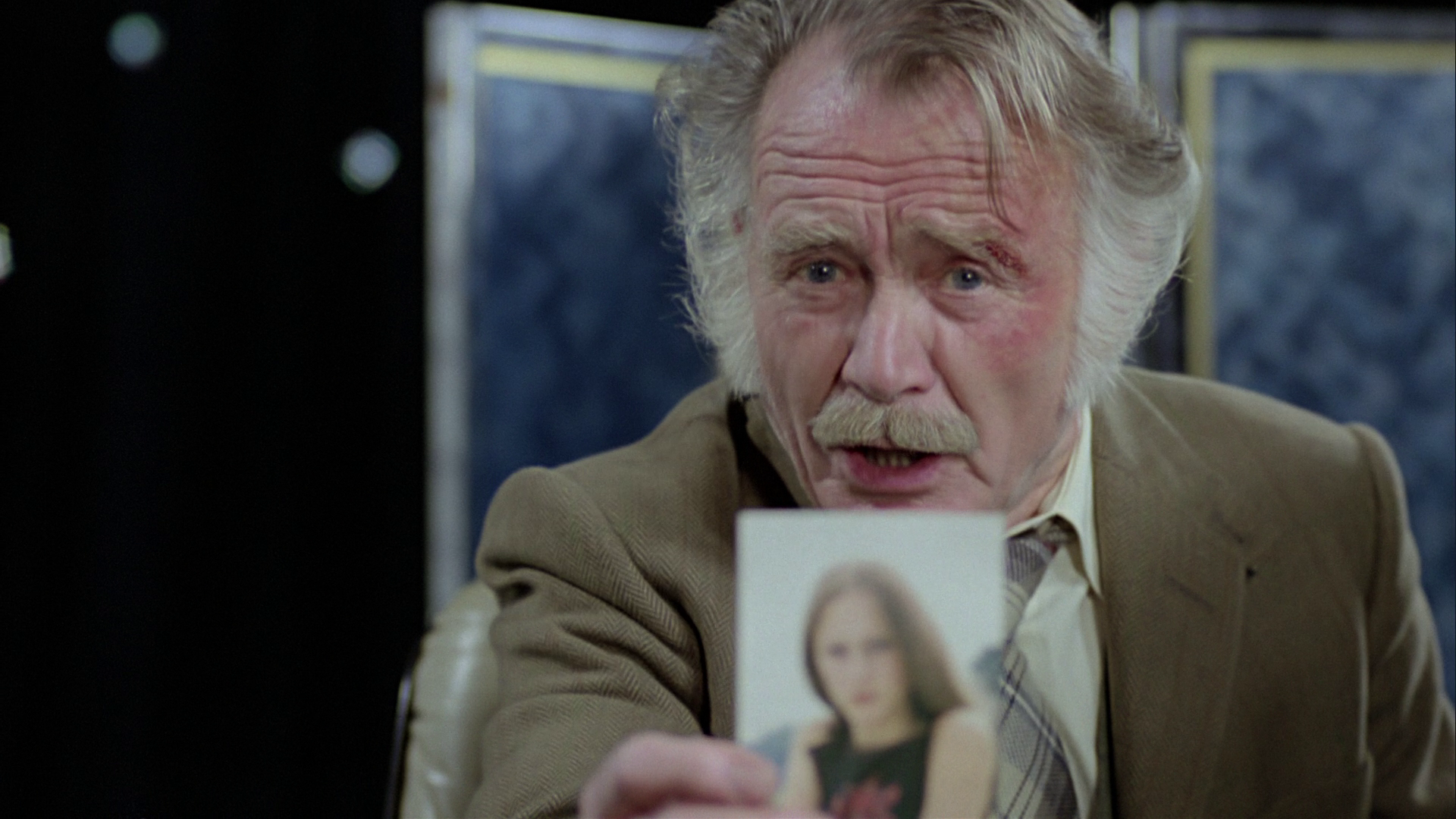

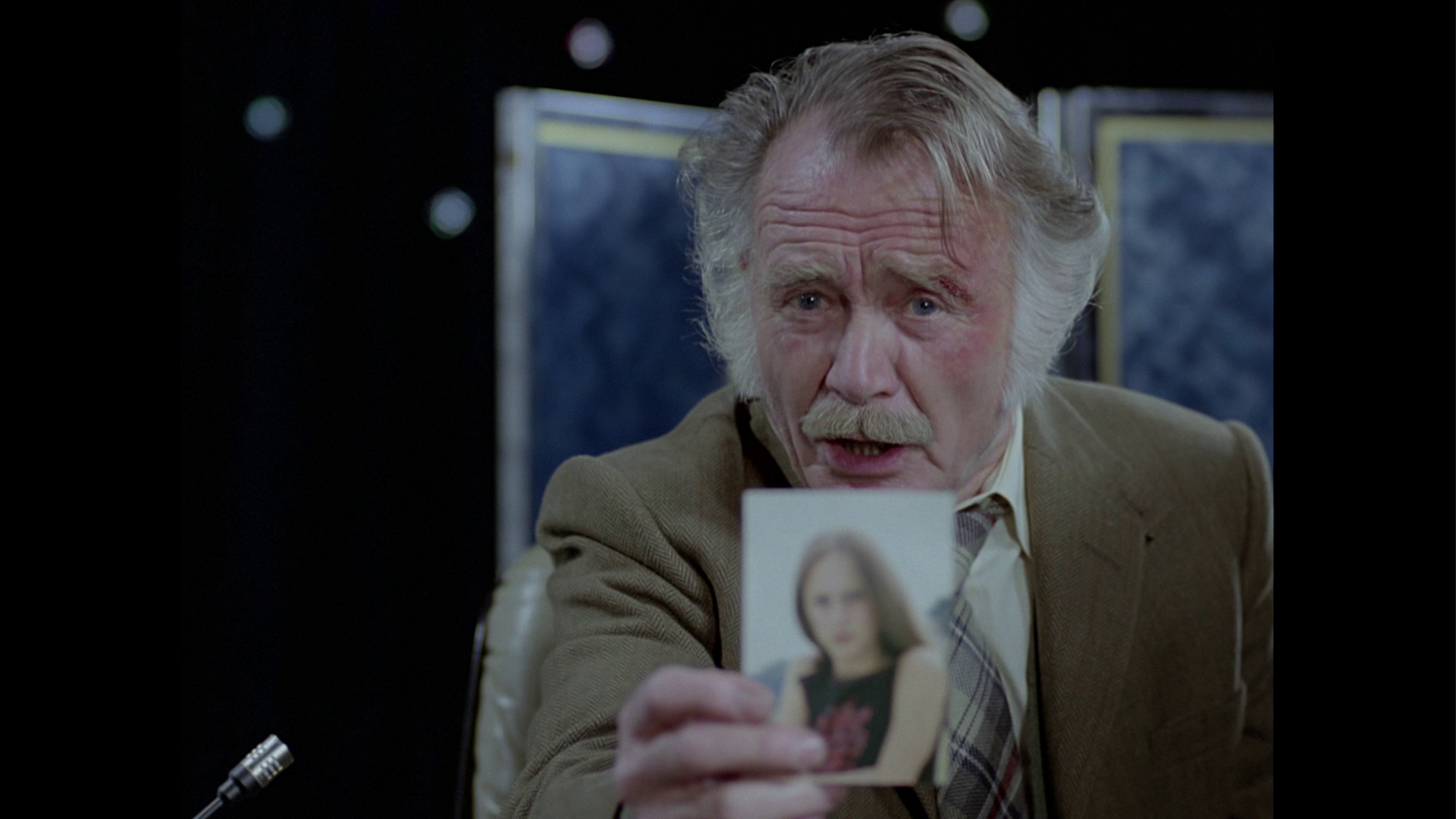

This programme is entitled ‘Hands in Space’. Kapp and Quatermass are to be interviewed during a live broadcast depicting the collaboration between Russian cosmonauts and American astronauts, who working together are building a new space station. (The interviewer, Toby Gough, played by Neil Stacy, is forbidden from mentioning the disastrous space mission that Quatermass himself was associated with – an allusion to the events of The Quatermass Experiment.) However, Quatermass expresses strong criticisms of the project and hijacks the programme to beg the audience for help finding his missing granddaughter, Hettie Carlson (Rebecca Saire). Shortly afterwards, disaster strikes and the people in the studio watch on as the video monitor shows the space shuttles and the partially-constructed station being crushed by an invisible force, the astronauts and cosmonauts killed.  The event is initially believed to be an act of sabotage, and owing to his angry criticisms of the project the Americans believe that Quatermass has some knowledge of who may be behind it. Kapp ushers Quatermass away, taking him to his home – which is near an observatory and radio telescope that Kapp works with several other scientists: Tommy Roach (Bruce Parchese), Frank Chen (David Yip) and Alison Thorpe (Brenda Ficker). There, Quatermass also meets Kapp’s family: his wife Clare (Barbara Kellerman) and his two young children, Debbie (Joanna Joseph) and Sarah (Sophie Kind). The event is initially believed to be an act of sabotage, and owing to his angry criticisms of the project the Americans believe that Quatermass has some knowledge of who may be behind it. Kapp ushers Quatermass away, taking him to his home – which is near an observatory and radio telescope that Kapp works with several other scientists: Tommy Roach (Bruce Parchese), Frank Chen (David Yip) and Alison Thorpe (Brenda Ficker). There, Quatermass also meets Kapp’s family: his wife Clare (Barbara Kellerman) and his two young children, Debbie (Joanna Joseph) and Sarah (Sophie Kind).

On their way to Kapp’s home, Quatermass and Kapp encounter the Planet People: a mass of hippie-like youths who are hostile to science and learning, and chant ‘Leh! Leh!’ whilst they take part in a bizarre pilgrimage of some kind. The observatory is near a small five thousand year old stone circle that the Kapp’s have named ‘The Stumpy Men’, and The Planet People pass by The Stumpy Men on their way to a larger stone circle, Ringstone Round (which, according to Clare Kapp, is ‘even older than Stonehenge’ and ‘could have been the prototype’). The Planet People arrive at Ringstone Round, and the (armed) police who are there fail to keep them away from the stone circle. Overreacting, the police open fire and shoot at the Planet People; the Planet People overcome the police, and a mysterious beam of light shoots from the sky, turning the Planet People (and the police officers) to dust. Episode two, ‘Lovely Lightning’, opens with the revelation that the Planet People have been essentially cremated by the blast. The surviving Planet People believe that their comrades have been beamed up to ‘the Planet, all of ‘em’. It seems the Planet People believe ‘the Planet’ to be some form of paradise. They refer to the ray as ‘lovely lightning’.  However, it seems that one of the Planet People, Isabel (Annabelle Lanyon), has survived – barely. Isabel, who was on the periphery of the blast, is badly burnt, blinded by the light and partially deafened by the explosion. Quatermass and Kapp battle with the Planet People, eventually rescuing Isabel and taking her back to the observatory. Meanwhile, one of the Planet People, Kickalong (Ralph Arliss), takes the position as their leader and picks up one of the police’s sten guns. Later, Kickalong’s influence turns the Planet People increasingly violent, and they murder an elderly farmer in order to get access to the food that he has stockpiled. However, it seems that one of the Planet People, Isabel (Annabelle Lanyon), has survived – barely. Isabel, who was on the periphery of the blast, is badly burnt, blinded by the light and partially deafened by the explosion. Quatermass and Kapp battle with the Planet People, eventually rescuing Isabel and taking her back to the observatory. Meanwhile, one of the Planet People, Kickalong (Ralph Arliss), takes the position as their leader and picks up one of the police’s sten guns. Later, Kickalong’s influence turns the Planet People increasingly violent, and they murder an elderly farmer in order to get access to the food that he has stockpiled.

The local District Commissioner, Annie Morgan (Margaret Tyzack), arrives at the observatory and asks Quatermass and Kapp what took place at Ringstone Round. They explain the events to her. They establish communication with Chuck Marshall (Tony Sibbald), an American and former colleague of Quatermass, who tells them that another blast killing ‘twelve or thirteen thousand kids’ has taken place in Brazil. Quatermass and Annie plan to take Isabel to London, where they will be able to stabilise her and also run some tests. It seems that a large number of similar ‘cullings’ of young people by the alien force have taken place all over the world, including in the cities. As they drive through London Annie inadvertently takes Quatermass and Isabel through an area that is torn apart by running battles between the Badders and the Blue Brigade. Annie’s vehicle is caught in the crossfire between these two gangs, and Quatermass is pulled from it. Annie, however, manages to escape to the nearby hospital. Meanwhile, Kapp returns home to find that the Planet People have congregated near The Stumpy Men for yet another of the blasts – and Clare and the children may have been caught in it.  Episode three, ‘What Lies Beneath’, sees a wounded Quatermass taken in by a community of elderly people who live in the tunnels between the cars that exist beneath the upper layers of a wrecker’s yard. There, he meets a former perfumier, Chisholm (Donald Eccles). The encounter gives Quatermass an idea: the alien beam that cremates the young people gathering at the ancient sites is attracted by their ‘scent’, using this to zero in on the sites where the incidents have taken place. Quatermass suggests that the current events are an echo of events that happened five millennia previously, and the ancient gathering sites where such incidents took place were marked with stone circles that functioned as ‘guidance beams set in the Earth for next time’. Episode three, ‘What Lies Beneath’, sees a wounded Quatermass taken in by a community of elderly people who live in the tunnels between the cars that exist beneath the upper layers of a wrecker’s yard. There, he meets a former perfumier, Chisholm (Donald Eccles). The encounter gives Quatermass an idea: the alien beam that cremates the young people gathering at the ancient sites is attracted by their ‘scent’, using this to zero in on the sites where the incidents have taken place. Quatermass suggests that the current events are an echo of events that happened five millennia previously, and the ancient gathering sites where such incidents took place were marked with stone circles that functioned as ‘guidance beams set in the Earth for next time’.

Arriving at the hospital, Annie struggles with bureaucratic red tape and the official denial of the incident that has taken place at Ringstone Round. However, she is eventually allowed to admit Isabel. Whilst Isabel is being monitored, Annie and the doctors watch in astonishment as Isabel levitates and then explodes. Meanwhile, Quatermass is ‘rescued’ from the makeshift community in the wrecker’s yard by the military, and he is ushered to the television studio where the popular ‘Tittupy Bumpity’ show is interrupted for an emergency broadcast, involving Quatermass, that deals with the events at Ringstone Round and the other ancient sites across the world. Meanwhile, the Russians and the Americans plan to launch a space mission to communicate with the alien intelligence. ‘Forget about trying to get through to it’, Quatermass tells them, ‘The ripe crop can’t appeal to the reaper [….] The human race is being harvested’. The Russian and American space mission fails catastrophically, the shuttle being blasted with the beam that is directed towards the Earth. Meanwhile, back in London, gladiatorial games have been scheduled to take place at Wembley Stadium, but Quatermass suggests that this too may be built on an ancient gathering site. Quatermass expresses belief that the beam will strike at Wembley Stadium during the ‘games’. In response to this, a government minister asks Quatermass, ‘Do you really suggests Wembley Stadium is an ancient site?’ ‘The “sacred turf”, they call it’, Quatermass responds, ‘I wonder what’s underneath’. Quatermass and Annie rush to Wembley Stadium but are ambushed as the beam strikes.  Episode four, ‘An Endangered Species’, opens with Quatermass stumbling out of Wembley Stadium’s car park, apparently the only survivor. The sky has turned a sickly green owing to the pollution from the ashes of the seventy thousand people who have been killed by the blast at Wembley Stadium. ‘The sun!’, one of the Pay Cops – the private police force – says, ‘The sun, it’s turned…’ ‘It’s like vomit’, Quatermass declares for him. Episode four, ‘An Endangered Species’, opens with Quatermass stumbling out of Wembley Stadium’s car park, apparently the only survivor. The sky has turned a sickly green owing to the pollution from the ashes of the seventy thousand people who have been killed by the blast at Wembley Stadium. ‘The sun!’, one of the Pay Cops – the private police force – says, ‘The sun, it’s turned…’ ‘It’s like vomit’, Quatermass declares for him.

Quatermass suggests that the beam that is directed towards the Earth may simply be ‘a machine – of incredible sophistication, but a machine nonetheless’, and that the intelligence which built the machine may be long dead. The threat, Quatermass argues, is unknowable; the only hope is to stop it harvesting more humans. Working with his assumption that the beam is attracted by the ‘scent’ and hormonal secretions of humans gathered at these ancient spots, Quatermass works with a Russian scientist, Gurov (Brewster Mason). The pair attempt to devise a way to set a trap for the machine. Quatermass intends to use Kapp’s radio telescope to ‘put out the analogue of a human presence. The sound of them, the smell of them. Their secretions; hormones; pheromones’ and use this for bait to attract the attention of the beam. ‘And the poison?’, Kapp asks. ‘There’ll be poison’, Quatermass tells him: ‘thirty-five kilotons of thermonuclear blast, focused upwards’. Quatermass scoffs at Kapp’s suggestion that this might destroy whatever device is directing the beam, telling the younger scientist that ‘I can’t. There’s no question. Sting it. Send a shock through its ganglia. It’ll be like a man who stepped on a hornet. That’s all’. Peter Hutchings has suggested that the differences between the Quatermass stories and contemporaneous American science fiction television and cinema is in their approach to the individual’s relationship with society: Hutchings has argued that ‘the Quatermass stories have a tendency to view individuals as existing primarily within and in relation to groups, institutions and collectives’ (Hutchings, 2004: 341). So ‘the world of Quatermass’ is populated not by ‘lovers or families [… or very many] free-standing individuals’ but rather by ‘scientists, soldiers, policemen, politicians, journalists, workers’ (ibid.). For Hutchings, this view of society and the roles of people within it is dependent on ‘a notion of the people developed and circulated in Britain during the Second World War’: the idea, put forward in wartime propaganda as a means of unifying ‘a working class alienated from ideas of national unity after the experience of the Depression’, that ‘the people as a national collective absorbed and superseded the individual, where romance and desire were expendable, even frivolous, given Britain’s troubled circumstances, and where the nuclear family that had been disrupted by war was replaced by the group as the prime site of interaction and mutual support’ (ibid.).  As Hutchings suggests, in the early Quatermass serials there is very little dissent (ibid.). In fact, the voice of dissent in the early serials usually comes from Quatermass himself, who persuades those around him to look at issues from another perspective. Certainly, John Mills’ Quatermass, in this final Quatermass serial, performs a similar role: for example, he states his case against the Hands in Space programme quite directly during the live television broadcast. On the other hand, what’s different about the final Quatermass serial is the extent to which dissent and conflict is depicted as rife within society: Kapp’s instant distrust of the Planet People, whom he perceives as ‘drop outs’; the constant violence within the capital; the battles between the Badders and the Blue Brigade. In this serial, it is the alien force which unites people: in one sequence, the Planet People wade through a part of London in which the Badders and Blue Brigade are fighting one another. A few of the Planet People are shot, but within minutes both the Badders and Blue Brigade have put aside their guns to join the Planet People in their chant, and all of these young people are led to their deaths at Wembley Stadium: the alien force and the compulsion to migrate to the ancient gathering places acts as a Pied Piper of sorts. In the earlier Quatermass serials and films, the social order is disrupted part way through the narrative (for example, the riot that takes place towards the end of Quatermass and the Pit); on the other hand, Quatermass begins with the social order already ripped asunder, Quatermass stumbling into London completely unprepared, in search of Hettie, after leaving behind his quiet home in the West of Scotland. As Hutchings suggests, in the early Quatermass serials there is very little dissent (ibid.). In fact, the voice of dissent in the early serials usually comes from Quatermass himself, who persuades those around him to look at issues from another perspective. Certainly, John Mills’ Quatermass, in this final Quatermass serial, performs a similar role: for example, he states his case against the Hands in Space programme quite directly during the live television broadcast. On the other hand, what’s different about the final Quatermass serial is the extent to which dissent and conflict is depicted as rife within society: Kapp’s instant distrust of the Planet People, whom he perceives as ‘drop outs’; the constant violence within the capital; the battles between the Badders and the Blue Brigade. In this serial, it is the alien force which unites people: in one sequence, the Planet People wade through a part of London in which the Badders and Blue Brigade are fighting one another. A few of the Planet People are shot, but within minutes both the Badders and Blue Brigade have put aside their guns to join the Planet People in their chant, and all of these young people are led to their deaths at Wembley Stadium: the alien force and the compulsion to migrate to the ancient gathering places acts as a Pied Piper of sorts. In the earlier Quatermass serials and films, the social order is disrupted part way through the narrative (for example, the riot that takes place towards the end of Quatermass and the Pit); on the other hand, Quatermass begins with the social order already ripped asunder, Quatermass stumbling into London completely unprepared, in search of Hettie, after leaving behind his quiet home in the West of Scotland.

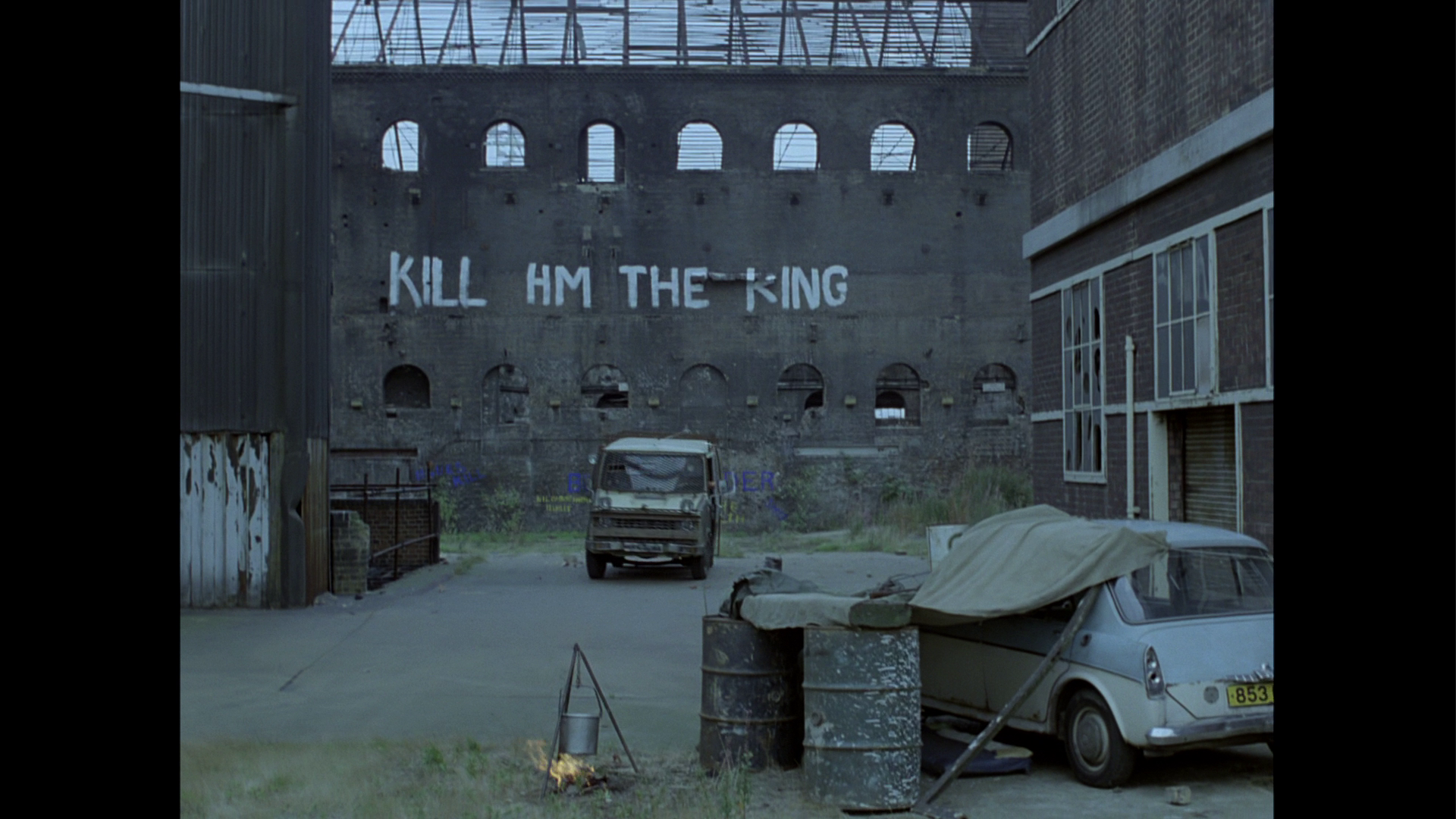

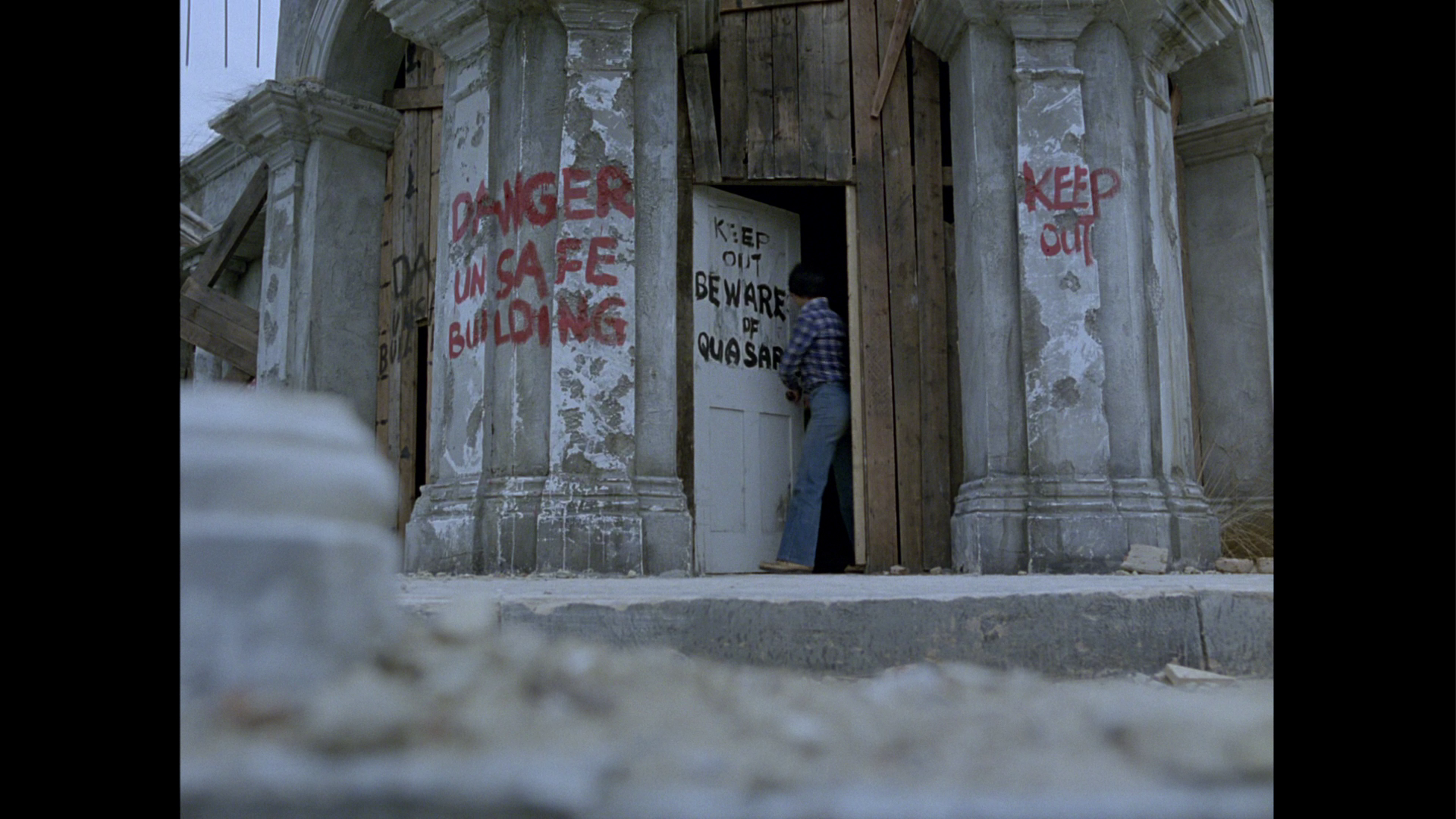

Quatermass foregrounds its themes of social breakdown and urban decay, depicted through the iconography graffiti (the slogan ‘Kill HM the King’ is a recurring motif here, and later shots of a framed picture of a young Prince Charles suggest he is the target of this hatred) and youth gangs like the Badders and the Blue Brigade. The series extrapolates from the unrest in Europe during the 1970s, with the actions of the street gangs recalling both the battles between mods and rockers during the 1960s and the attacks of groups like the Brigate Rosse in Italy during the 1970s: the Badders, we are told within the first episode, picked their name because they were inspired by the West German Baader-Meinhof Group (the Red Army Faction/Rote Armee Fraktion). However, the Badders’ violence (apparently) lacks the political motivation of the Baader-Meinhof Group, seemingly being inspired purely by a love of violence itself.  Within the series, people live in makeshift refugee camps, presenting corpses as latter-day saints and selling books as a fuel source (‘GUARANTEED TO BURN WELL’, reads a sign above a cart filled with books in one of the camps that Kapp and Quatermass drive past). The first episode begins with a brief moment of narration (later revealed to be by Gurov, a character who isn’t formally introduced to us until much later in the series) declaring that ‘In the last quarter of the Twentieth Century, the whole world seemed to sicken. Civilised institutions, whether old or new, fell, as if some primal disorder was reasserting itself. And men asked themselves, why should this be?’ All of this is set against an energy crisis and the privatisation of the police force: alongside the regular police, Pay Cops roam the streets. Wearing painted motorcycle helmets and bulky stab-proof vests, they negotiate the ongoing battles between the Badders and the Blue Brigade, and they are often seen in the countryside on horseback – like the knights of yore. The iconography of cities ripped apart with violence taps into the zeitgeist of post-apocalyptic science fiction of the late 1970s and 1980s: the opening television broadcast amidst chaos recalls the opening sequences of George A Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), and the depiction of roaming street gangs is reminiscent of those found in films like Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979) and later post-apocalyptic pictures such as Enzo Castellari’s The Bronx Warriors (1982) and John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1982). (The privatised police force, the ‘Pay Cops’, also look surprisingly like some of the authoritarian figures of The Bronx Warriors.) Within the series, people live in makeshift refugee camps, presenting corpses as latter-day saints and selling books as a fuel source (‘GUARANTEED TO BURN WELL’, reads a sign above a cart filled with books in one of the camps that Kapp and Quatermass drive past). The first episode begins with a brief moment of narration (later revealed to be by Gurov, a character who isn’t formally introduced to us until much later in the series) declaring that ‘In the last quarter of the Twentieth Century, the whole world seemed to sicken. Civilised institutions, whether old or new, fell, as if some primal disorder was reasserting itself. And men asked themselves, why should this be?’ All of this is set against an energy crisis and the privatisation of the police force: alongside the regular police, Pay Cops roam the streets. Wearing painted motorcycle helmets and bulky stab-proof vests, they negotiate the ongoing battles between the Badders and the Blue Brigade, and they are often seen in the countryside on horseback – like the knights of yore. The iconography of cities ripped apart with violence taps into the zeitgeist of post-apocalyptic science fiction of the late 1970s and 1980s: the opening television broadcast amidst chaos recalls the opening sequences of George A Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), and the depiction of roaming street gangs is reminiscent of those found in films like Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979) and later post-apocalyptic pictures such as Enzo Castellari’s The Bronx Warriors (1982) and John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1982). (The privatised police force, the ‘Pay Cops’, also look surprisingly like some of the authoritarian figures of The Bronx Warriors.)

In episode one, Quatermass’ visit to the city is a shock to him: he is surprised to hear automatic gunfire in the streets and even more surprised when a group of youths accost him and threaten him with violence (‘Take his teeth out’, the gang leader asserts). When Kapp rescues Quatermass, a visibly shaken Quatermass observes, ‘They were enjoying it’. ‘Yes, of course they were’, Kapp tells him. Arriving at the television studio, the interviewer Toby notices the bruises and abrasions on Quatermass’ face. Quatermass tells Toby that he has been mugged. ‘It happens all the time’, Toby replies nonchalantly. ‘You too?’, Quatermass asks. ‘Broken jaw last time’, Toby tells him. Shortly after, Quatermass questions Kapp about the violence he has witnessed in the city during his brief visit there. ‘They’re just bland about it’, Kapp tells Quatermass, ‘They call it “urban collapse” and it’s “nobody’s fault”’. ‘Yes, but the savagery…’, Quatermass begins, lost for words. ‘You should see Paris or Rotterdam’, Kapp informs him, suggesting the violence is not just endemic within Britain but has spread across the globe. ‘Little suburban streets with… with dead bodies’, a shocked Quatermass says, ‘I’d never have believed it till I came down here this week’. Shortly afterwards, he tells Kapp – during a discussion of Quatermass’ missing granddaughter Hettie – ‘Do you know they won’t even list them [missing people]? They’ve so many missing they’ve just given up’. In episode two, whilst on the way to deliver Isabel to London, Quatermass hears gunfire and Annie tells him, ‘When you hear it, just keep going. That’s the best rule. If they jump out in front of you, just drive at them’. Quatermass expresses shock at Annie’s declaration, and Annie asks him, ‘What went wrong? Was it the kids? Oh, Professor… Bernard… what went into them all? The blind rage, as if we had to have it’. In response to this, Quatermass offers a hypothesis: that ‘an immense power [that has been] approaching Earth for decades’ has somehow affected ‘the most vulnerable organisms’, the very young.  Quatermass perceives the superpowers to be directly responsible for the level of social breakdown he has witnessed, suggesting that smaller countries like Britain have been destroyed by their influence. When he is interviewed on the ‘Hands in Space’ programme, Quatermass shocks the interviewer and the producers of the show by declaring that he is ‘ashamed to think that I might have contributed in any way to this disgusting charade’. ‘What we’re looking at there is a wedding’, Quatermass says, in reference to the live feed showing the astronauts working on the space station and in a speech which seems to act as the voice of the series’ author Nigel Kneale, ‘A symbolic wedding between a corrupt democracy and a monstrous tyranny. Two superpowers, full of diseases [….] Political diseases, economic diseases, social diseases. And their infections are too strong for us, the small countries. When we catch them, we die. We’re dying now. And they mock us with that thing [the space project]’. Kneale’s work has sometimes been claimed to express a dislike of American culture generally, but in truth his perspective was usually more critical of the process of Americanisation and the coercion of British culture into adopting more ‘American’ values; this is something which is foregrounded in Quatermass’ denouncement of the ‘Hands in Space’ programme. Quatermass perceives the superpowers to be directly responsible for the level of social breakdown he has witnessed, suggesting that smaller countries like Britain have been destroyed by their influence. When he is interviewed on the ‘Hands in Space’ programme, Quatermass shocks the interviewer and the producers of the show by declaring that he is ‘ashamed to think that I might have contributed in any way to this disgusting charade’. ‘What we’re looking at there is a wedding’, Quatermass says, in reference to the live feed showing the astronauts working on the space station and in a speech which seems to act as the voice of the series’ author Nigel Kneale, ‘A symbolic wedding between a corrupt democracy and a monstrous tyranny. Two superpowers, full of diseases [….] Political diseases, economic diseases, social diseases. And their infections are too strong for us, the small countries. When we catch them, we die. We’re dying now. And they mock us with that thing [the space project]’. Kneale’s work has sometimes been claimed to express a dislike of American culture generally, but in truth his perspective was usually more critical of the process of Americanisation and the coercion of British culture into adopting more ‘American’ values; this is something which is foregrounded in Quatermass’ denouncement of the ‘Hands in Space’ programme.

Amidst the chaos and social unrest, the authorities have tried to mitigate this explosion of brutality with a return to gladiatorial combat. Wembley Stadium, Quatermas is informed by Kipp, has been renamed ‘The Killing Ground’ and is the site of a vaguely-defined form of violent combat. ‘They actually encourage it?’, Quatermass asks Kapp upon hearing about this for the first time. ‘Well, contain it’, Kapp offers, ‘At least, that was the notion’. ‘Like the Roman arenas’, Quatermass observes. ‘Right. Gladiators [….] Oh, well, as long as it keeps them happy’, Kapp says. Ironically, the new name of Wembley Stadium takes on added meaning when Quatermass discovers that it was built on the site of one of the ancient gathering places and is one of the likely targets for the ‘harvesting’ of the humans gathered there.  Into this, Kneale works elements of media satire and explores the role of television, and a fascination with its processes, in the way that he had in The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972) and The Year of the Sex Olympics (Michael Elliott, 1968). The ‘bread and circuses’ attitude alluded to in the rebranding of Wembley Stadium as ‘The Killing Ground’, a site in which violent entertainment is presented for the masses in the hope that this will somehow curb the violence that is endemic within society, is also suggested through the use of the medium of television within the series. The ‘Hands in Space’ programme is a fairly recognisable talk show, though one that has an obvious propagandistic function in terms of promoting the ongoing space project, a collaboration between Russia and America; Quatermass’ expression of a dissenting opinion about this project leads to the programme being rapidly taken off air. However, in episode three Quatermass, after he has been evacuated from the hideout of the elderly folk living in the wrecker’s yard, is taken once again to the TV studio. This time, it is being used for a bizarre cabaret-style programme in which dancers deliver a highly sexualised routine in front of a giant banana and a huge figure of a reclining nude woman, both made out of foam. The dancers unashamedly thrust their derrieres into the camera, as Quatermass watches on in disbelief. The show is taken off air for an emergency broadcast dealing with the events that have been taking place at the stone circles and other ancient gathering grounds. The director of the show complains: ‘But “Tittupy Bumpity” is the only show anyone watches anymore’. The title suggests a children’s show, but the programme is anything but. It seems an easy conclusion to reach that ‘Tittupy Bumpity’ was Kneale’s thinly-veiled critique of the BBC’s use of the sexualised dance routines of Pan’s People – but as with The Year of the Sex Olympics, Kneale’s criticism of popular forms of entertainment that chase the easy audience through ‘lowest common denominator’ programming and increased sexualisation of their content seems more prophetic with each passing year. Into this, Kneale works elements of media satire and explores the role of television, and a fascination with its processes, in the way that he had in The Stone Tape (Peter Sasdy, 1972) and The Year of the Sex Olympics (Michael Elliott, 1968). The ‘bread and circuses’ attitude alluded to in the rebranding of Wembley Stadium as ‘The Killing Ground’, a site in which violent entertainment is presented for the masses in the hope that this will somehow curb the violence that is endemic within society, is also suggested through the use of the medium of television within the series. The ‘Hands in Space’ programme is a fairly recognisable talk show, though one that has an obvious propagandistic function in terms of promoting the ongoing space project, a collaboration between Russia and America; Quatermass’ expression of a dissenting opinion about this project leads to the programme being rapidly taken off air. However, in episode three Quatermass, after he has been evacuated from the hideout of the elderly folk living in the wrecker’s yard, is taken once again to the TV studio. This time, it is being used for a bizarre cabaret-style programme in which dancers deliver a highly sexualised routine in front of a giant banana and a huge figure of a reclining nude woman, both made out of foam. The dancers unashamedly thrust their derrieres into the camera, as Quatermass watches on in disbelief. The show is taken off air for an emergency broadcast dealing with the events that have been taking place at the stone circles and other ancient gathering grounds. The director of the show complains: ‘But “Tittupy Bumpity” is the only show anyone watches anymore’. The title suggests a children’s show, but the programme is anything but. It seems an easy conclusion to reach that ‘Tittupy Bumpity’ was Kneale’s thinly-veiled critique of the BBC’s use of the sexualised dance routines of Pan’s People – but as with The Year of the Sex Olympics, Kneale’s criticism of popular forms of entertainment that chase the easy audience through ‘lowest common denominator’ programming and increased sexualisation of their content seems more prophetic with each passing year.

The series offers quite a direct criticism of New Age beliefs, through the representation of the Planet People and their belief that they will be rewarded by being transported to ‘the Planet’. Through their examination of the Planet People, the Badders and the Blue Brigade, Kneale’s scripts offer a strong critique of the herd mentality and the tendency of young to gather in crowds and gangs and express anti-intellectual sentiments. Kneale’s fiction often displays a criticism of mindlessness and the ‘sheep mentality’. Here, this criticism is expressed directly by Quatermass, who reflects on ‘These great gatherings. They’re another freak of our times. Huge assemblies. Mindless, enormous. Supposedly to listen to some leader or pop star, but really just to crowd together’. ‘Or to fight’, Annie adds. ‘Yes, more and more’, Quatermass concedes.  The Planet People are essentially a death cult, asserting that ‘Rockets make holes in the skin of the world. They tear it open’ and believing that they will be transported to live on a new planet, their version of paradise. They gather at the ancient meeting grounds, where they are turned to ash by the alien ray. (At the time of the series’ broadcast, the Planet People’s bizarre beliefs, their manipulation by Kickalong and their mass suicides seemed to echo both Charles Manson’s ‘family’ and the then-recent events in Jonestown, Guyana; in the years since its first broadcast, these scenes have gained added resonance following similar events such as the siege at Waco in 1993 and the mass suicide of the Heaven’s Gate cult in 1997.) ‘They infest the land’, Kapp tells Quatermass in reference to the Planet People, ‘like lemmings in search of the sea’. Kapp is equally cynical about the Planet People, going on to tell Quatermass, ‘I want a generation gap between me and them. I hate them because they’ve given up’. ‘It’s not a world to be young in anymore’, Quatermass observes. ‘Was it ever?’, Kapp asks. ‘Not like this’, Quatermass tells him. (Ironically though, when asked at the television studio ‘What have you been doing all these years?’, Quatermass replies, ‘Well, I think I’ve been what they call a “drop out”’: he’s opted out of society, choosing to live in isolation in his cottage in the West of Scotland.) The Planet People are essentially a death cult, asserting that ‘Rockets make holes in the skin of the world. They tear it open’ and believing that they will be transported to live on a new planet, their version of paradise. They gather at the ancient meeting grounds, where they are turned to ash by the alien ray. (At the time of the series’ broadcast, the Planet People’s bizarre beliefs, their manipulation by Kickalong and their mass suicides seemed to echo both Charles Manson’s ‘family’ and the then-recent events in Jonestown, Guyana; in the years since its first broadcast, these scenes have gained added resonance following similar events such as the siege at Waco in 1993 and the mass suicide of the Heaven’s Gate cult in 1997.) ‘They infest the land’, Kapp tells Quatermass in reference to the Planet People, ‘like lemmings in search of the sea’. Kapp is equally cynical about the Planet People, going on to tell Quatermass, ‘I want a generation gap between me and them. I hate them because they’ve given up’. ‘It’s not a world to be young in anymore’, Quatermass observes. ‘Was it ever?’, Kapp asks. ‘Not like this’, Quatermass tells him. (Ironically though, when asked at the television studio ‘What have you been doing all these years?’, Quatermass replies, ‘Well, I think I’ve been what they call a “drop out”’: he’s opted out of society, choosing to live in isolation in his cottage in the West of Scotland.)

When Quatermass first sees the Planet People, he asks Kapp about them, observing that they ‘don’t seem violent’. Kapp informs Quatermass that the Planet People ‘are violent in a different way: to human thought’. They demonstrate a virulent brand of anti-intellectualism, with a particular sense of hostility directed towards the field of science. After the incident at Ringstone Round in which a large number of the Planet People are cremated by the blast from the sky, the remaining Planet People express their belief that their friends have gone to ‘the Planet’, a paradise of some kind. Clare declares, ‘I don’t understand. I don’t want to understand’. One of the surviving Planet People tells Clare, ‘Stop trying to know things’. Later, in episode four, Kickalong, who has elected himself as the leader of the Planet People, suggests to Kapp that some people killed in the blasts may not be taken up to ‘the Planet’ owing to being ‘spoiled’ by learning, ‘too much think and talk’: instead of being transported to the paradise that the Planet People imagine, these ‘spoiled’ people ‘just get spilled away’ – and it is this ‘spillage’ that has polluted the skies, turning them green. ‘If you want to come with us’, Kickalong tells Kapp, ‘you’ve got to get it all out of your brain [….] All the muck you learned, every bit’. ‘But you can’t unlearn’, Kapp protests. In response, Kickalong simply declares that Kapp is held back by ‘All them words in there’ – and taps his head.  Ultimately, The series is ultimately profoundly fatalistic: there is no hope of destroying the enemy or understanding it completely – only frightening it away. Quatermass suggests that the beam could be directed by a machine, the creators of which may no longer survive. There is no hope of communicating with them, or it, and therefore no means of understanding the reason for the ‘attacks’ – though Quatermass suggests that ‘Something was taken’ in each event, ‘some trace [….] Perhaps a flavour, to enrich the lifestyles of inconceivable beings [….] To amuse them’. Ultimately, The series is ultimately profoundly fatalistic: there is no hope of destroying the enemy or understanding it completely – only frightening it away. Quatermass suggests that the beam could be directed by a machine, the creators of which may no longer survive. There is no hope of communicating with them, or it, and therefore no means of understanding the reason for the ‘attacks’ – though Quatermass suggests that ‘Something was taken’ in each event, ‘some trace [….] Perhaps a flavour, to enrich the lifestyles of inconceivable beings [….] To amuse them’.

Some of the motifs from Quatermass (Stonehenge, the ‘harvesting’ of young people) worked their way into the script for Halloween III: Season of the Witch (Tommy Lee Wallace, 1982), for which Kneale contributed an early draft that was subsequently revised considerably. Legend has it that Kneale walked away from the project after producer Dino De Laurentiis demanded a greater emphasis on violence. However, Kneale’s recurring focus on the ritual, and the conflict between science and superstition is evident throughout the film; and the film’s premise of a television broadcast which causes the deaths of young people can be traced back to an unproduced script that Kneale wrote in the 1960s, The Big Big Giggle. (That said, the references to Stonehenge were added after Kneale abandoned Halloween III, with Kneale’s drafts referencing the dolmens instead.) Reflecting on this script, John Carpenter later said that ‘it was great, but it was odd, and there was this … anti-Irish bitterness throughout the story’ (Carpenter, quoted in Cumbow, 2000: 69; ellipsis in original). Carpenter and Kneale disagreed when Carpenter suggested to Kneale that the film’s audience ‘comes to these movies to have fun and to be scared’, and in response Kneale asserted, ‘I don’t care about the audience’ (Carpenter, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). Kneale’s Halloween III was ‘three-fourths of a great script’ but was hampered, for Carpenter, by the fact that ‘there was this kind of disillusioned old man behind it’ (Carpenter, quoted in ibid.). Carpenter suggested that ‘I could never figure it out until I read his novelization of The Quatermass Conclusion. I think if anybody has any doubts about the changes that have gone on in his [Kneale’s] life since his early work, you should read that. He’s an angry man who doesn’t understand what the world has become, and he really doesn’t like people very much’ (Carpenter, quoted in ibid.).  This sense of Kneale being ‘out of touch’ with the modern world was a criticism that has, over the years (and especially at the time of its original broadcast), been often leveled against Quatermass, with its curious depiction of the hippie-like Planet People – who seemed positively quaint when set against the punk youth subculture that prevailed when the serial was first broadcast. Some of this has to do with the fact that the script for Quatermass had been drafted much earlier, in the late-1960s: an earlier, abandoned, production of Quatermass IV (as it was then titled) had been set in motion by the BBC in 1973, but the BBC abandoned shooting after completing some model shots for the space sequences and being denied permission to film at Stonehenge. (This issue was neatly sidestepped in the final production by Kneale rewriting the script for episode three to relocate the climax from Stonehenge to Wembley Stadium.) The project’s forecast budgets of £200,000 was considered too expensive, and it was shelved. As a consequence, when the script was revised and reworked for production by Euston Films in 1978, a number of the ideas seemed slightly outdated. However, time has been kind to the series, thanks in large part to the cannibalistic trend for youth cultures to return to, and feed off, earlier youth trends: where the Planet People may have seemed comically quaint when placed in contrast with the punks and skinheads of 1979, the resurgence of New Age beliefs in the 21st Century makes them seem suddenly a little more contemporary and ‘relevant’. This sense of Kneale being ‘out of touch’ with the modern world was a criticism that has, over the years (and especially at the time of its original broadcast), been often leveled against Quatermass, with its curious depiction of the hippie-like Planet People – who seemed positively quaint when set against the punk youth subculture that prevailed when the serial was first broadcast. Some of this has to do with the fact that the script for Quatermass had been drafted much earlier, in the late-1960s: an earlier, abandoned, production of Quatermass IV (as it was then titled) had been set in motion by the BBC in 1973, but the BBC abandoned shooting after completing some model shots for the space sequences and being denied permission to film at Stonehenge. (This issue was neatly sidestepped in the final production by Kneale rewriting the script for episode three to relocate the climax from Stonehenge to Wembley Stadium.) The project’s forecast budgets of £200,000 was considered too expensive, and it was shelved. As a consequence, when the script was revised and reworked for production by Euston Films in 1978, a number of the ideas seemed slightly outdated. However, time has been kind to the series, thanks in large part to the cannibalistic trend for youth cultures to return to, and feed off, earlier youth trends: where the Planet People may have seemed comically quaint when placed in contrast with the punks and skinheads of 1979, the resurgence of New Age beliefs in the 21st Century makes them seem suddenly a little more contemporary and ‘relevant’.

Euston Films shot the production on 35mm, at a time when much British television was still shot predominantly in studios on videotape (with 16mm inserts often used for location work). Founded in 1971, Euston Films had abandoned the use of videotape, delivering gritty shows shot on location with 16mm film – such as the final two series of Special Branch (1973-4) and The Sweeney (1974-8). (One of Euston Film’s biggest successes was Minder, which began broadcasting in 1979, the same year as Quatermass.) Filmed entirely on 35mm, one of the factors allowing the series to be edited down to feature length for theatrical release in America (as The Quatermass Conclusion), Quatermass was an expensive production for Euston Films, costing around £1.2 million. Verity Lambert, the chief executive of Euston Films at the time of Quatermass’s production, once said ‘I think it was the most expensive thing we attempted at Euston Films at that point. And we felt that the only way we could justify the expense was to make sure we could re-edit it into a film which could possibly have theatrical release as well as have a four-parter’ (Lambert, quoted in Chapman, 2006: 41).   Apart from featuring a to-be-expected abbreviated version of the narrative (the narrative events of episode one are condensed into the first hour of the film, for example), The Quatermass Conclusion omits the whole of episode three’s reference to the elderly people who live in the wrecker’s yard, with new footage filmed for the subsequent hospital sequences: in the film, Quatermass doesn’t get separated from Annie and is present as a witness when Isabel explodes in the hospital. Otherwise, the film retains the narrative structure of the series – but the series, which expands upon and clarifies many of the plot points within the story, is a far more rewarding experience. Kneale also adapted the scripts into a novel, also published in 1979, which expands upon some of the events in the story and develops the relationship between Quatermass and Annie. The series’ success with audiences was impacted by the ITV technicians strike of August 1979, which led to the broadcast of the heavily-advertised first episode – originally intended to be in September – to be delayed until October.   The contents of the discs are as follows: DISC ONE (Blu-ray): Episode 1: ‘Ringstone Round’ (54:26) Episode 2: ‘Lovely Lightning’ (54:25) Episode 3: ‘What Lies Beneath’ (52:47) Episode 4: ‘An Endangered Species’ (53:31) Textless Film Titles (1:59) Episode Recaps (4:25) DISC TWO (Blu-ray) The Quatermass Conclusion (106:41) Textless End Titles (2:53) Trailer (mute) (4:32) Gallery (2:51)

Video

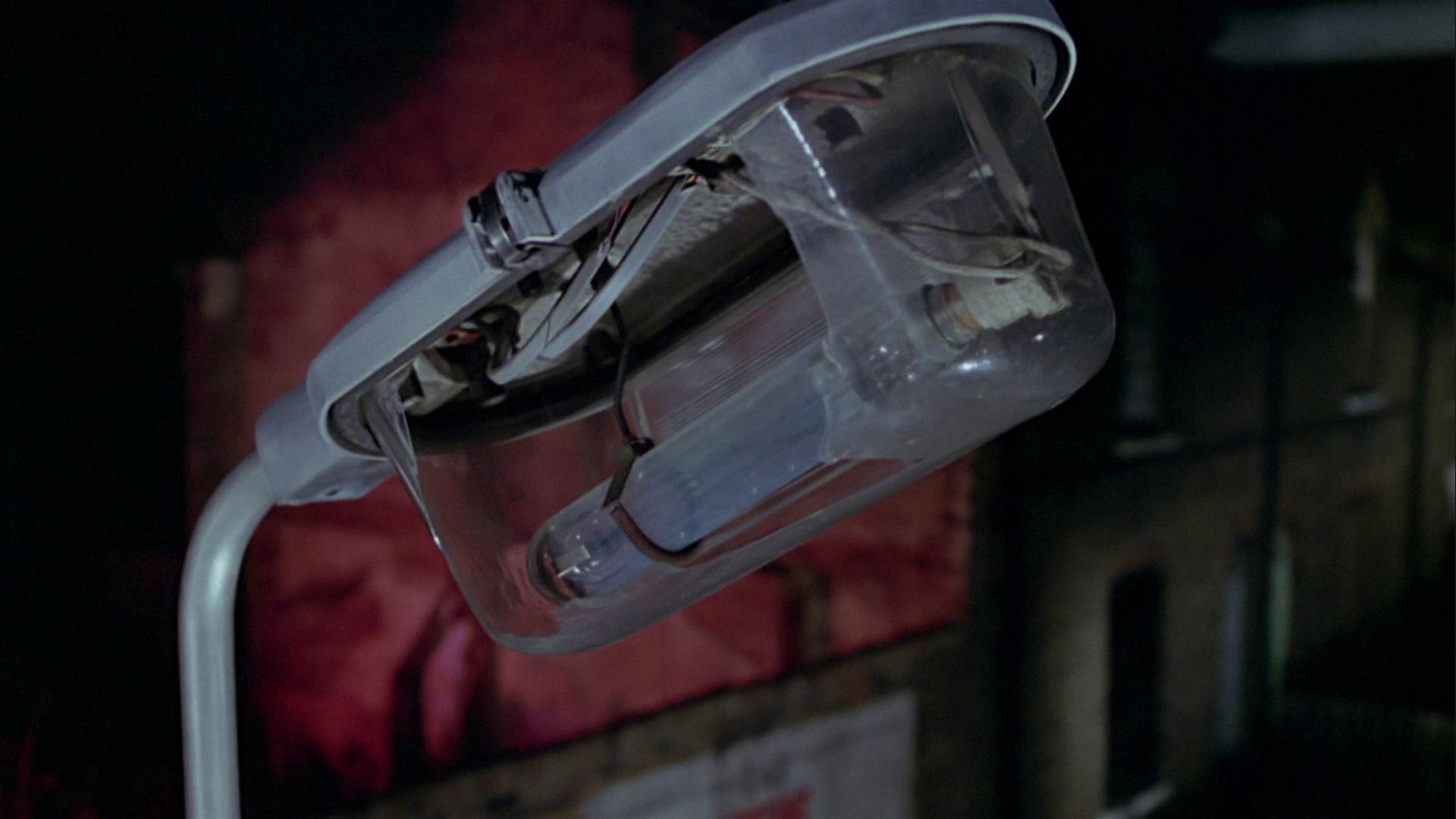

Disc one presents all four episodes of Quatermass, each episode taking up approximately 10Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) of the series is in its original broadcast ratio of 1.33:1. Remastered from the original 35mm negative, the presentation of the series on this disc is simply beautiful, displaying excellent, well-balanced contrast levels and a sparkling level of detail. Colour consistency is vastly improved over previous home video releases too. Fine detail is evident in close-ups, although there’s a very, very slight ‘smoothness’ to some of this detail which suggests an element of digital noise reduction has been applied – though, it has to be said, nothing too detrimental. All of the strengths of this presentation, and their impact on one’s enjoyment of the series, is evident from the opening shot of episode one: a close-up of a smashed street lamp at night, a red billboard behind it. It’s a striking, symbolic shot, made all the more potent in this Blu-ray presentation which gives depth and vibrancy to an image that has, in previous home video versions, always had a ‘flatness’ to it. Disc one presents all four episodes of Quatermass, each episode taking up approximately 10Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation (using the AVC codec) of the series is in its original broadcast ratio of 1.33:1. Remastered from the original 35mm negative, the presentation of the series on this disc is simply beautiful, displaying excellent, well-balanced contrast levels and a sparkling level of detail. Colour consistency is vastly improved over previous home video releases too. Fine detail is evident in close-ups, although there’s a very, very slight ‘smoothness’ to some of this detail which suggests an element of digital noise reduction has been applied – though, it has to be said, nothing too detrimental. All of the strengths of this presentation, and their impact on one’s enjoyment of the series, is evident from the opening shot of episode one: a close-up of a smashed street lamp at night, a red billboard behind it. It’s a striking, symbolic shot, made all the more potent in this Blu-ray presentation which gives depth and vibrancy to an image that has, in previous home video versions, always had a ‘flatness’ to it.

The biggest differences between this HD presentation and the previous DVD release of the series from Clearvision, aside from the level of detail present here, are in the contrast levels and the colour. Where both the contrast and the reds seemed boosted in the series’ previous DVD incarnation, here the contrast is more balanced and the skin tones look much more natural (except, of course, for when the sky turns sickly green in episodes three and four). For the record, the break bumpers are intact on the episodes, and the Thames logo is present at the start (though the latter, oddly, seems to be a digital recreation of the original Thames logo, with slightly different placing of the letters).  On disc two, The Quatermass Conclusion is presented in a 1080p presentation (also using the AVC codec) in the 1.78:1 ratio, which would seem to be roughly commensurate with the ratio of its cinema release. With this presentation, the compositions are opened up slightly on the left and right-hand sides of the frame but (obviously) cropped at the top and bottom of the image (some screen grabs comparing the framing of the film and television versions are included below). Also remastered from the original film elements, this presentation of the film displays the same strengths as the presentation of the series on disc one. In sum, both the series and the film get a very pleasing presentation on this release, with a strong encode on both discs that carries this material through to the viewer without any distracting digital artifacts or anything of that sort. On disc two, The Quatermass Conclusion is presented in a 1080p presentation (also using the AVC codec) in the 1.78:1 ratio, which would seem to be roughly commensurate with the ratio of its cinema release. With this presentation, the compositions are opened up slightly on the left and right-hand sides of the frame but (obviously) cropped at the top and bottom of the image (some screen grabs comparing the framing of the film and television versions are included below). Also remastered from the original film elements, this presentation of the film displays the same strengths as the presentation of the series on disc one. In sum, both the series and the film get a very pleasing presentation on this release, with a strong encode on both discs that carries this material through to the viewer without any distracting digital artifacts or anything of that sort.

NB. Some larger screen grabs from each episode and the feature film are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

With the series, the viewer is presented with the option of the original sound mix, presented in LPCM 2.0 stereo, or a newly-created DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix. Both are very clean and clear, with good range. There’s a brief moment in episode three (between the 16 and 18 minute markers) where the sound on both tracks becomes a little ‘muddy’ and indistinct – like listening to it underwater. It’s a little more noticeable on the LPCM 2.0 stereo track but is present on the 5.1 track also, and so is probably a feature of the original film materials. With the series, the viewer is presented with the option of the original sound mix, presented in LPCM 2.0 stereo, or a newly-created DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix. Both are very clean and clear, with good range. There’s a brief moment in episode three (between the 16 and 18 minute markers) where the sound on both tracks becomes a little ‘muddy’ and indistinct – like listening to it underwater. It’s a little more noticeable on the LPCM 2.0 stereo track but is present on the 5.1 track also, and so is probably a feature of the original film materials.

The new 5.1 mix demonstrates some effective, but subtle, separation effects that distinguish it (naturally) from the original two-channel sound mix and give it added ‘oomph’ (for example, in the organ chords used in the opening theme). However, the original materials are handled with respect in this 5.1 presentation and even the most devout of audio purists will find it satisfying, though many will probably default to the original audio mix. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included on the disc.

Extras

Disc one includes:  - Textless film titles (1:59). This is the opening titles sequence of The Quatermass Conclusion, presented mute and without text. - Textless film titles (1:59). This is the opening titles sequence of The Quatermass Conclusion, presented mute and without text.

- Episode Recaps (4:25). These are the episode recaps with which the second, third and fourth episodes were accompanied. The first recap is presented without sound. Disc two includes: - Textless End Titles (2:53). The clue is in the descriptive title, but this is the closing sequence of The Quatermass Conclusion, once again presented sans text and sound. - Trailer (mute) (4:32). This trailer prepared for the release of The Quatermass Conclusion is presented without sound. - Gallery (2:51). A stills gallery containing on-set photographs.

Overall

The series is a somewhat didactic distillation of many of the preoccupations of Kneale’s fiction: Quatermass offers a none-too-subtle criticism of mindless anti-intellectualism, mealy-mouthed politicians, the herd mentality (expressed through the slavish fashions and attitudes of youth cultures – not just hippies but all forms of youth cultures), the ‘cult of personality’, violence-as-spectacle, and the Americanisation of British culture. Ridiculed at the time for its ‘quaint’ depiction of youth culture, in Quatermass now seems increasingly prophetic. The material is handled confidently by veteran director Piers Haggard. Though Kneale was apparently displeased with Mills’ performance as Quatermass, feeling that the actor lacked the gravitas needed for the part, Mills’ Quatermass is a much more human figure: his search for his granddaughter gives him a connection to the world that was lacking in the character’s previous incarnations and renders him frail. The threats to Quatermass within this series are very real, as is evident from the opening sequence of the first episode in which he is attacked by members of one of the street gangs on his way to the television studio. It’s an ultimately rather bleak series, depicting Britain as a passive little country which has been pulled into the gravitational orbit of the big superpowers where it is slowly disintegrating – sort of an exploration of the Roche limit translated into cultural terms. The threat from space can’t be communicated with or understood: all we can do, Quatermass argues, is frighten it away – perhaps only temporarily. The series is a somewhat didactic distillation of many of the preoccupations of Kneale’s fiction: Quatermass offers a none-too-subtle criticism of mindless anti-intellectualism, mealy-mouthed politicians, the herd mentality (expressed through the slavish fashions and attitudes of youth cultures – not just hippies but all forms of youth cultures), the ‘cult of personality’, violence-as-spectacle, and the Americanisation of British culture. Ridiculed at the time for its ‘quaint’ depiction of youth culture, in Quatermass now seems increasingly prophetic. The material is handled confidently by veteran director Piers Haggard. Though Kneale was apparently displeased with Mills’ performance as Quatermass, feeling that the actor lacked the gravitas needed for the part, Mills’ Quatermass is a much more human figure: his search for his granddaughter gives him a connection to the world that was lacking in the character’s previous incarnations and renders him frail. The threats to Quatermass within this series are very real, as is evident from the opening sequence of the first episode in which he is attacked by members of one of the street gangs on his way to the television studio. It’s an ultimately rather bleak series, depicting Britain as a passive little country which has been pulled into the gravitational orbit of the big superpowers where it is slowly disintegrating – sort of an exploration of the Roche limit translated into cultural terms. The threat from space can’t be communicated with or understood: all we can do, Quatermass argues, is frighten it away – perhaps only temporarily.

This Blu-ray release of the series is excellent, a huge leap forwards from the previously available DVD release. The inclusion of the feature film edit, The Quatermass Conclusion, is incredibly welcome, and the presentation of both that and the series itself is first class. This is a must-buy release which for fans of British television, and especially fans of Nigel Kneale, will arguably be one of the most significant home video releases of the year. References: Chapman, James, 2006: ‘Quatermass and the origins of British television sf’. In: Cook, John R & Wright, Peter (eds), 2006: British Science Fiction Television: A Hitchhiker’s Guide. London: I B Tauris: 21-51 Cumbow, Robert, 2000: Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Hutchings, Peter, 2004: ‘We’re the Martians Now: British SF Invasion Fantasies of the 1950s and 1960s’. In: Redmond, Sean (ed), 2004: Liquid Metal: The Science Fiction Film Reader. Columbia University Press: 337-46 Screen grabs comparing the television version with The Quatermass Conclusion Quatermass:

The Quatermass Conclusion:

Quatermass:

The Quatermass Conclusion:

Quatermass:

The Quatermass Conclusion:

Episode 1:

Episode 2:

Episode 3:

Episode 4:

|

|||||

|