|

|

Sabotage (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - 101 Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Sabotage (Tibor Takacs, 1996) Sabotage (Tibor Takacs, 1996)

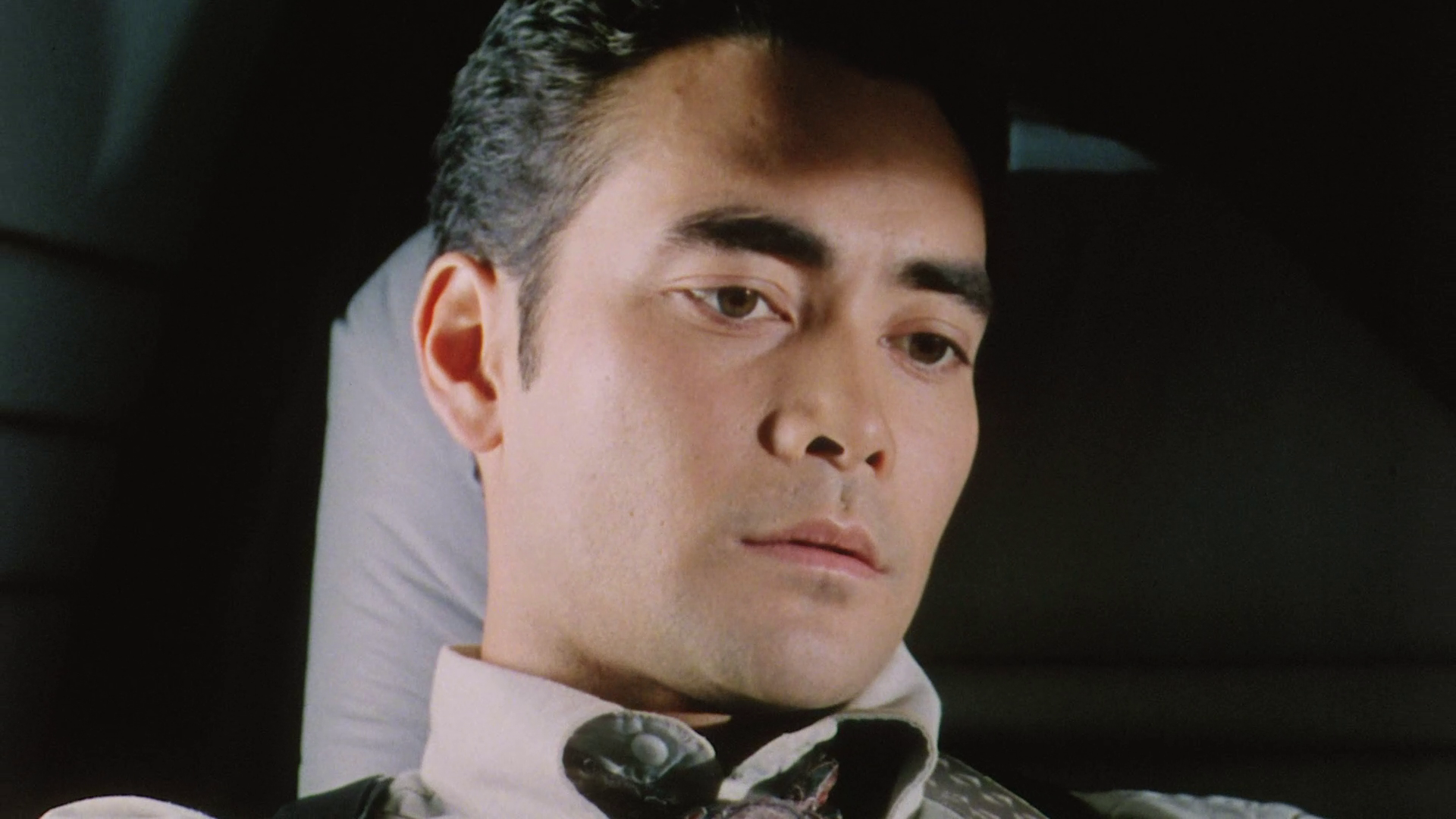

Mark Dacascos, a Hawaiian martial artist who seemed to be a rising star within action films of the mid-1990s, never quite acquired the fame of the martial artists-turned-actors who arrived slightly earlier on the scene, such as Wesley Snipes, Jean-Claude Van Damme, Dolph Lundgren and, of course, the likes of Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris. This was despite the fact that Dacascos was handsome, had screen charisma aplenty and was also a talented martial artist. Dacascos’ career as an action star began in the early/mid-1990s with pictures such as American Samurai (Sam Firstenberg, 1992) and Sheldon Lettich’s Only the Strong (1993), and was consolidated with starring roles in Steve Wang’s Drive (1997) and Christophe Gans’ Crying Freeman (1995). Some of these films made a fairly large impact amongst fans of action cinema, but by the end of the decade and the start of the next century Dacascos became associated predominantly with action movies made for the straight-to-video market or produced for distribution to American cable channels. Some of this may have been to do with the timing of Dacascos’ acting career: coming a few years after the big boom in the late 1980s/early 1990s of martial arts-themed action films, following the impact on American filmmakers of Hong Kong action pictures by directors such as John Woo and Ringo Lam, Dacascos’ career as an actor coincided with the push towards increasingly spectacular blockbusters such as Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) and The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999). Interestingly, upon the release of The Matrix, the Wachowskis’ film invited comparisons with the Dacascos-starring Drive, released only two years prior, owing to both films exhibiting a strong influence of Hong Kong action cinema in their fast-and-furious martial arts scenes and use of wirework – the latter a novelty within US cinema at the time. (As if to consolidate the film’s Hong Kong connection, Drive was even released on VHS and DVD in the UK by Hong Kong Legends.)  In the film under discussion, Sabotage (Tibor Takacs, 1996), Dacascos stars alongside Carrie-Ann Moss, who of course went on to play Trinity in The Matrix. In this film, Dacascos plays Michael Bishop, who in the opening sequence is shown working as part of a two-man sniper team in Bosnia in 1993. Bishop has been sent to rescue four Serbian officers from the mujahideen who have taken them hostage. However, the operation doesn’t go as planned: it is interrupted by a lone man who causes Bishop’s spotter to get shot by the mujahideen. The rogue operative kills the mujahideen and murders the hostages too, before revealing himself to be Jason Sherwood (Tony Todd), a member of Bishop’s combat unit. Sherwood then shoots Bishop, leaving him for dead. In the film under discussion, Sabotage (Tibor Takacs, 1996), Dacascos stars alongside Carrie-Ann Moss, who of course went on to play Trinity in The Matrix. In this film, Dacascos plays Michael Bishop, who in the opening sequence is shown working as part of a two-man sniper team in Bosnia in 1993. Bishop has been sent to rescue four Serbian officers from the mujahideen who have taken them hostage. However, the operation doesn’t go as planned: it is interrupted by a lone man who causes Bishop’s spotter to get shot by the mujahideen. The rogue operative kills the mujahideen and murders the hostages too, before revealing himself to be Jason Sherwood (Tony Todd), a member of Bishop’s combat unit. Sherwood then shoots Bishop, leaving him for dead.

A title card announces: ‘3 Years Later. Baltimore, Maryland’. Bishop, now a bodyguard, is on a private jet owned by millionaire arms dealer Jeffrey Trent (Richard Coulter). Trent’s jet is landing in Baltimore airport when, unbeknownst to them, on the roof of a nearby hotel Sherwood is fixing in place a high-powered sniper rifle – such a powerful weapon that it needs to be bolted to the floor via a tripod in order to be operated efficiently – on the rooftop of a nearby hotel. When the plane lands, Sherwood fires the rifle. The high-powered bullet passes through Trent’s other bodyguard, killing the arms dealer immediately – and blasting a hole in the fuselage of the jet itself. Bishop manages to protect Susan Trent (Heidi von Palleske) and deduces how far away the sniper is and the angle that the bullet has been fired from. With this information, he concludes that the assassin is on top of the hotel. He heads for the hotel but is too late: Sherwood has already fled, killing a security guard during his escape.  Meanwhile, FBI Special Agent Louise Castle (Moss), a single mother, is called away from her daughter’s fifth birthday to investigate the shooting of Trent. There is some debate about the jurisdiction of the case, but as Castle tells a police detective, because ‘the first bullet crossed the perimeter of the airport’ the case belongs to the FBI. Bishop is immediately suspected of having something to do with the assassination of Trent (‘Mr Bishop, in most successful assassinations the bodyguards are killed with their principles’, Castle informs him, ‘Of those who aren’t, over half are somehow involved with the murder’). Meanwhile, FBI Special Agent Louise Castle (Moss), a single mother, is called away from her daughter’s fifth birthday to investigate the shooting of Trent. There is some debate about the jurisdiction of the case, but as Castle tells a police detective, because ‘the first bullet crossed the perimeter of the airport’ the case belongs to the FBI. Bishop is immediately suspected of having something to do with the assassination of Trent (‘Mr Bishop, in most successful assassinations the bodyguards are killed with their principles’, Castle informs him, ‘Of those who aren’t, over half are somehow involved with the murder’).

Bishop pays a visit to his old friend and teacher Professor Follenfant (John Neville). Follenfant tells Bishop that under cover of enacting humanitarian missions in wartorn countries, Trent was running guns across the world – including in Bosnia. ‘Who’d want Trent dead?’, Bishop asks. ‘The short list?’, Follenfant offers, ‘The Libyans, the Iranians, the Iraqis, the Germans, any number of swindled businessmen, spurned lovers’. The assassination of Mrs Trent leaves Bishop, once again, a survivor but implicates him further in the plot to murder both of the Trents. One of the assassins, Elliot Holden (Anderson Dixon), is killed – but he’s been set up as a patsy by Sherwood, who has deliberately equipped Holden with a rifle whose sights are misaligned. Holden’s death allows Sherwood to escape from the scene of the crime. Bishop’s former commanding officer, Nicholas Tollander (Graham Greene), is now with the CIA; he insists that Bishop is in some way guilty of the murders, or at least involved in the conspiracy to commit them, and pushes Castle to arrest Bishop. ‘You’re not authorised to act domestically’, Castle reminds Tollander. ‘That’s the beauty of covert operations’, Tollander suggests. ‘It’s not covert when you tell someone’, Castle responds – making it clear that she does not wish to become involved in acting as the agent of Tollander’s will. Bishop must fight to clear his name whilst exposing the true villains, and in doing so he enlists the help of Castle.  In Terrorism in American Cinema: An Analytical Filmography, 1960-2008, Robert Cettl discusses Sabotage. Cettle suggests that Dacascos has been ‘fortunate in his choice of projects’ and Takacs is ‘a competent B-movie director’ (Cettl, 2009: 231). The film itself, Cettl argues, offers ‘a look at the dichotomy between chance and fate in the lives of people who can never be truly free from their pasts’ (ibid.). The opening confrontation with the Serbian terrorists, and Sherwood’s intrusion into this, establishes ‘an unfinished game’ between the protagonist and antagonist, with Sherwood acting throughout the film as ‘the force of fate’ (ibid.). The film uses terrorism as a ‘springboard for the drama’, exploring the impact of such events on ‘counterterrorists involved in lives long after the initial terrorist threat has been resolved’ (ibid.: 231-2). The film’s villain, initially a part of the counterterrorism unit in Bosnia, uses the techniques associated with terrorism back home on American soil, employing these tactics ‘as a hallmark of his profession, refusing to relinquish its expediency’ (ibid.: 232). Furthermore, the film underscores the role the CIA plays ‘as sponsors of terrorism’, with the ‘CIA operatives here work[ing] on the basis of immorality as an operating principle, staging an assassination to look like an anti-terror rescue mission’ (ibid.). Alongside this, Bishop’s role in the lives of Castle and her fatherless daughter narrativises ‘the restoration of both patriarchy and family’ (ibid.). In Terrorism in American Cinema: An Analytical Filmography, 1960-2008, Robert Cettl discusses Sabotage. Cettle suggests that Dacascos has been ‘fortunate in his choice of projects’ and Takacs is ‘a competent B-movie director’ (Cettl, 2009: 231). The film itself, Cettl argues, offers ‘a look at the dichotomy between chance and fate in the lives of people who can never be truly free from their pasts’ (ibid.). The opening confrontation with the Serbian terrorists, and Sherwood’s intrusion into this, establishes ‘an unfinished game’ between the protagonist and antagonist, with Sherwood acting throughout the film as ‘the force of fate’ (ibid.). The film uses terrorism as a ‘springboard for the drama’, exploring the impact of such events on ‘counterterrorists involved in lives long after the initial terrorist threat has been resolved’ (ibid.: 231-2). The film’s villain, initially a part of the counterterrorism unit in Bosnia, uses the techniques associated with terrorism back home on American soil, employing these tactics ‘as a hallmark of his profession, refusing to relinquish its expediency’ (ibid.: 232). Furthermore, the film underscores the role the CIA plays ‘as sponsors of terrorism’, with the ‘CIA operatives here work[ing] on the basis of immorality as an operating principle, staging an assassination to look like an anti-terror rescue mission’ (ibid.). Alongside this, Bishop’s role in the lives of Castle and her fatherless daughter narrativises ‘the restoration of both patriarchy and family’ (ibid.).

When Bishop meets with Follenfant to discuss his predicament, Follenfant refers to Bishop as ‘a samurai without his shogun’, and to some extent the film resembles Japanese samurai films about ronin (masterless samurai) seeking revenge. (The connection between former Black Ops operatives and masterless ronin of feudal Japan would be consolidated in John Frankenheimer's film Ronin, released two years later.) Together, Bishop and Follenfant engage in a lengthy (and slightly didactic) discussion of chess, which for Follenfant ‘gives me the luxury of seeing all the men, anticipating all the moves. Life isn’t so forgiving’, he reminds Bishop: Follenfant is wheelchair bound owing to a bullet which he is unsure whether it came from an enemy or under orders from a ‘friendly’ bureaucrat who thought the professor’s lifestyle (his weakness for young men) made him a ‘security risk’. Follenfant reminds Bishop that ‘Indifference to chance is a great vanity in any game’.  The ‘game’, such as it is, involves the CIA and private arms dealers such as Trent. Trent, we are told, has been selling arms under the cover of providing humanitarian relief to wartorn countries. In turn, Trent has been bankrolled by the CIA. (The assassination of Trent, it is suggested, is an attempt upon the part of the CIA, represented through Tollander, to avoid the ‘embarrassment’ of their relationship with Trent being exposed.) Through the character of Trent, Sabotage makes vague allusions to the Iran-Contra scandal of the mid-1980s: the US government’s breaking of the arms embargo prohibiting the sale of weapons to Iran, in order to (illegally) fund the anti-Sandinista rebels in Nicaragua. Sabotage is ultimately a film that is deeply cynical about power and authority. Given the paradigms of the genre, it’s arguably no ‘spoiler’ to reveal that the film’s resolution sees Bishop and Castle safe but seemingly still ‘on the run’. The ‘game’, such as it is, involves the CIA and private arms dealers such as Trent. Trent, we are told, has been selling arms under the cover of providing humanitarian relief to wartorn countries. In turn, Trent has been bankrolled by the CIA. (The assassination of Trent, it is suggested, is an attempt upon the part of the CIA, represented through Tollander, to avoid the ‘embarrassment’ of their relationship with Trent being exposed.) Through the character of Trent, Sabotage makes vague allusions to the Iran-Contra scandal of the mid-1980s: the US government’s breaking of the arms embargo prohibiting the sale of weapons to Iran, in order to (illegally) fund the anti-Sandinista rebels in Nicaragua. Sabotage is ultimately a film that is deeply cynical about power and authority. Given the paradigms of the genre, it’s arguably no ‘spoiler’ to reveal that the film’s resolution sees Bishop and Castle safe but seemingly still ‘on the run’.

The film begins with Bishop, in Bosnia, acting as an agent of the will of the government. Then, following the disastrous outcome of his mission to rescue the Serbian officers from the mujahideen who are holding them captive, he ‘snaps to’ on Trent’s private jet – as if awakening from a nightmare. His subservience is underscored in a brief exchange with his colleague, who is killed by the same bullet that kills Trent: the bullet fired from Sherwood’s high-powered rifle is followed, in a (clumsy) computer-generated tracking shot, as it travels from the hotel to the airport, then shown in a side-on mid-shot passing through Bishop’s colleague and the body of Trent, before we finally see it blowing a hole in the fuselage of the jet. In the conversation that precedes the assassination of Trent, Bishop’s colleague looks at Bishop’s military boots and tells Bishop, ‘This job demands that we look smart, not like hired beef’. ‘We are hired beef’, Bishop reminds him. After Trent has been killed, Castle asks Bishop if he knows what Trent did. Bishop’s answer is simple: ‘Paid my salary’, he tells her. In a later scene, Castle looks at Bishop’s file and questions him about the three years that are missing from it, asking him what he did during that time. ‘What did I do?’, Bishop asks, ‘Everything they told me’.  However, as the narrative progresses, Bishop (together with Castle) becomes increasingly aware of the nature of Trent’s business and the government’s involvement in it. Bishop becomes a fugitive, aided and abetted by Castle; he is, in effect, a fall-guy or patsy comparable to those of classic films noir or more contemporaneous neo-noir pictures such as John Dahl’s The Last Seduction (1994). Bishop’s story is one of education, and then redemption, as he takes on the agents of the will of the corrupt CIA officials who are, through the murder of Trent, essentially ‘cleaning house’ – in much the same way as, in Bosnia, Sherwood attempted to ‘clean house’ by killing (or believed himself to have killed) Bishop following Sherwood’s mission to eradicate the mujahideen and ‘silence’ the Serbian officers rather than free them. When Sherwood shoots Bishop during the film’s Bosnia-set opening sequence, Sherwood tells him, ‘Nothing personal, Bishop […] Just business’. However, as the narrative progresses the ongoing battle between the two becomes increasingly personal – until it involves both Castle and her young daughter Melissa, who Sherwood kidnaps and uses as bait to lure Bishop and Castle into a ‘killing box’. However, as the narrative progresses, Bishop (together with Castle) becomes increasingly aware of the nature of Trent’s business and the government’s involvement in it. Bishop becomes a fugitive, aided and abetted by Castle; he is, in effect, a fall-guy or patsy comparable to those of classic films noir or more contemporaneous neo-noir pictures such as John Dahl’s The Last Seduction (1994). Bishop’s story is one of education, and then redemption, as he takes on the agents of the will of the corrupt CIA officials who are, through the murder of Trent, essentially ‘cleaning house’ – in much the same way as, in Bosnia, Sherwood attempted to ‘clean house’ by killing (or believed himself to have killed) Bishop following Sherwood’s mission to eradicate the mujahideen and ‘silence’ the Serbian officers rather than free them. When Sherwood shoots Bishop during the film’s Bosnia-set opening sequence, Sherwood tells him, ‘Nothing personal, Bishop […] Just business’. However, as the narrative progresses the ongoing battle between the two becomes increasingly personal – until it involves both Castle and her young daughter Melissa, who Sherwood kidnaps and uses as bait to lure Bishop and Castle into a ‘killing box’.

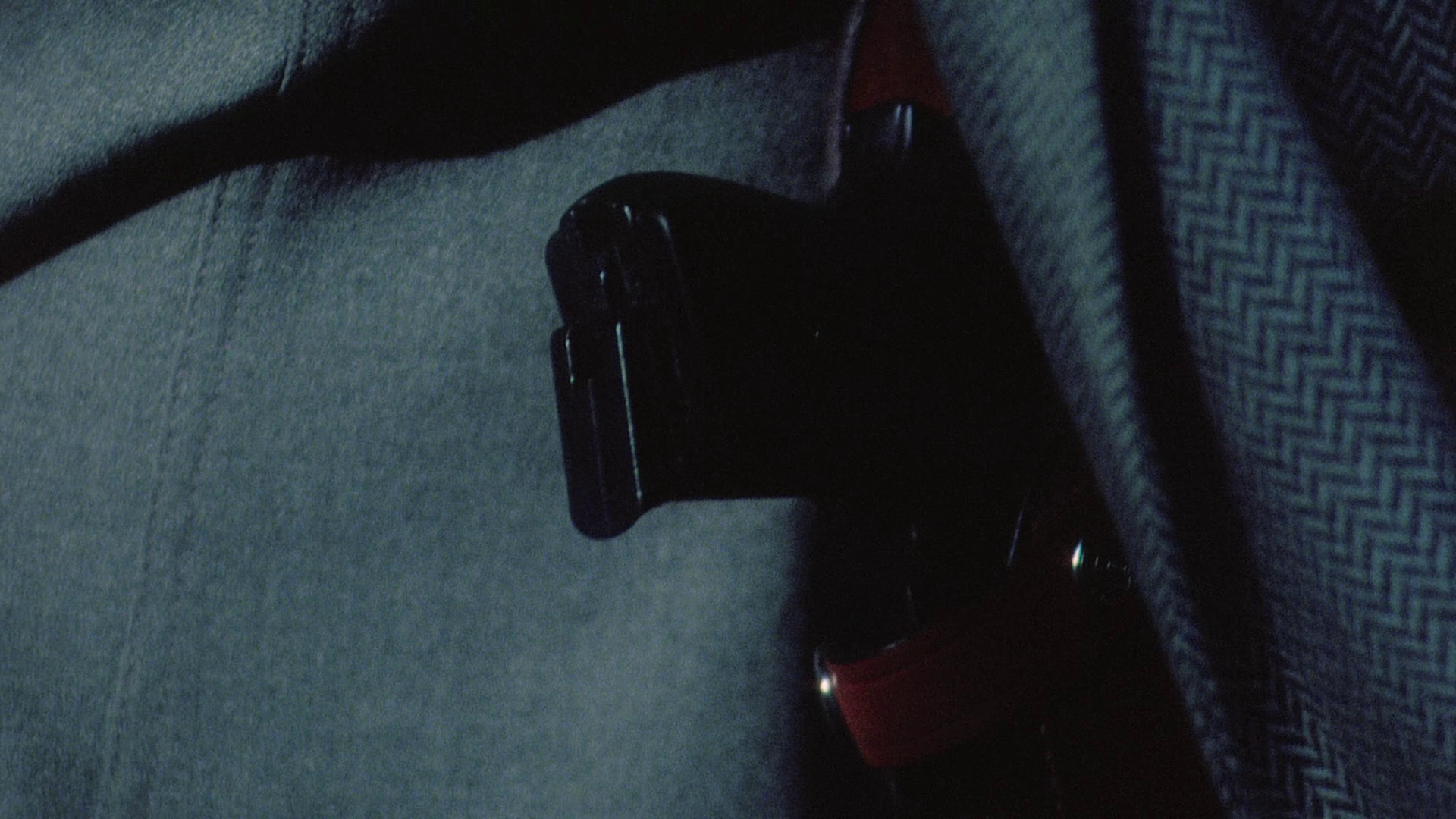

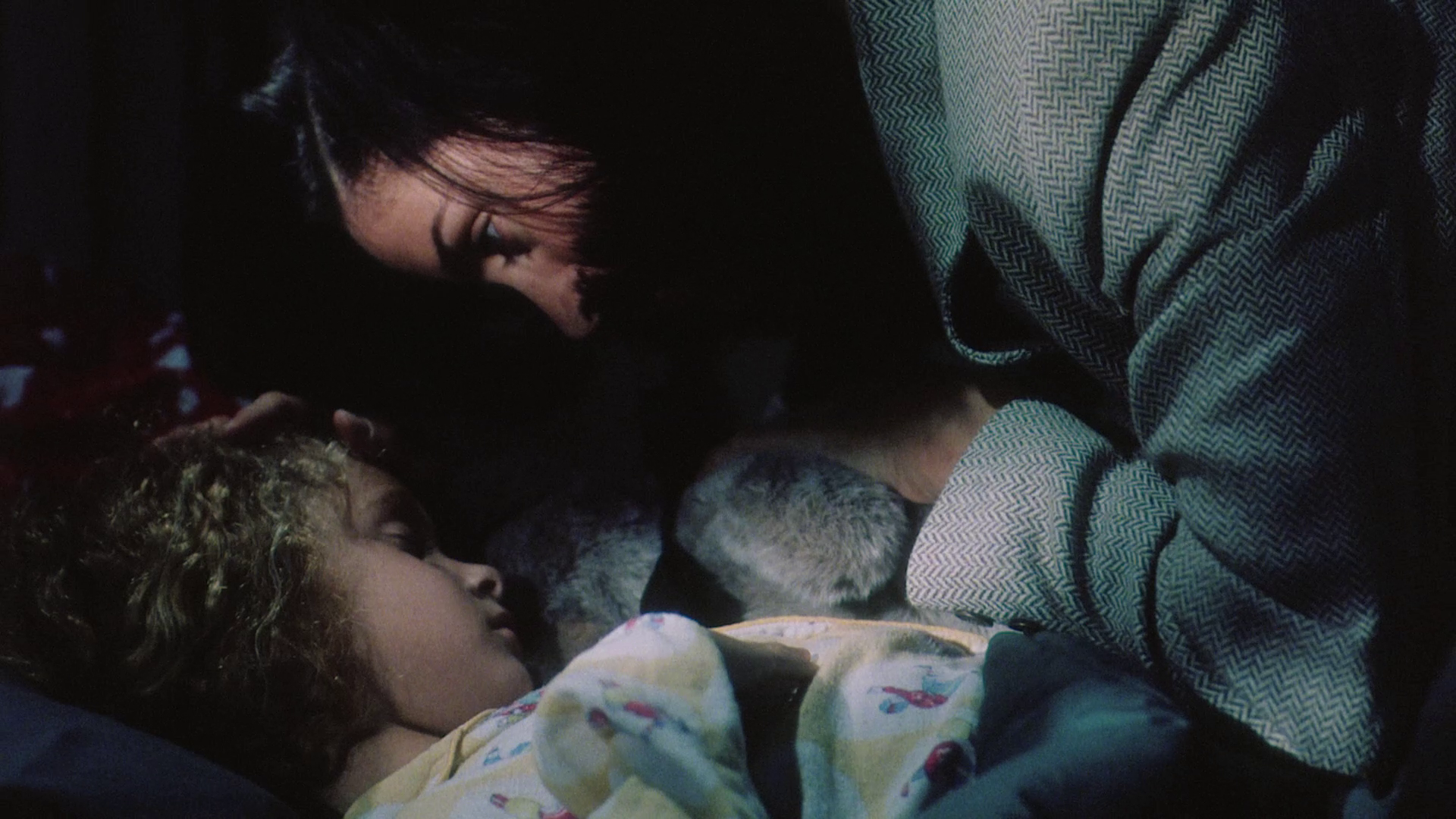

Castle’s relationship with her daughter offsets the drama and political intrigue of the main plot. In the first sequence in which she appears, Castle abandons her daughter to a babysitter – on the child’s fifth birthday, no less – in order to attend the scene of Trent’s assassination. When Castle finally returns home, it is at night. Her daughter, Melissa, is already in bed. Castle leans forwards and kisses the child on her forehead. Melissa opens her eyes very subtly, without alerting Castle, and a point-of-view shot from Melissa’s perspective shows Castle’s jacket hanging open and, close to her breast, a shoulder holster holding Castle’s handgun. Melissa closes her eyes and goes back to sleep, Takacs cutting to a side-on mid-shot of the pair. It’s a brief moment that underscores Castle’s commitment to her job whilst also symbolically suggesting the extent to which Castle’s maternal role is associated with violence and her ability to ‘protect’ Melissa.    There’s clever crosscutting of the scene in which Castle talks about the case with the coroner, and Bishop discusses Trent’s murder with Follenfant – and, as the conversations overlap and dovetail, the two protagonists learn the same facts about Trent, that he was an international arms dealer with a long list of enemies. The crosscutting of this material deepens the relationship between Bishop and Castle.  There are some witty exchanges between Castle and Bishop which are presented in a deadpan style by both Takacs and the actors. When Castle and Bishop first meet, Castle compliments Bishop on his gun. Bishop asks her if she knows the muzzle velocity of it. ‘350 metres per second’, she responds, ‘but I always think it’s much more impressive in feet, don’t you?’ ‘It’s my gun, not my penis’, Bishop says dryly. Towards the end of the film, Bishop turns Sherwood’s high-powered sniper rifle on its owner, as Sherwood drives away. Bishop bolts the gun to the roof of a car and fires it. ‘Got him!’, Bishop declares prematurely before watching Sherwood’s car escape in a dip in the road. ‘Fuck!’, Bishop exclaims. ‘Mommy, he just said a bad word’, Melissa says. To this, Castle responds: ‘He’s entitled to right now, sweetie’, then adds, ‘Bishop, nail the fucker!’ There are some witty exchanges between Castle and Bishop which are presented in a deadpan style by both Takacs and the actors. When Castle and Bishop first meet, Castle compliments Bishop on his gun. Bishop asks her if she knows the muzzle velocity of it. ‘350 metres per second’, she responds, ‘but I always think it’s much more impressive in feet, don’t you?’ ‘It’s my gun, not my penis’, Bishop says dryly. Towards the end of the film, Bishop turns Sherwood’s high-powered sniper rifle on its owner, as Sherwood drives away. Bishop bolts the gun to the roof of a car and fires it. ‘Got him!’, Bishop declares prematurely before watching Sherwood’s car escape in a dip in the road. ‘Fuck!’, Bishop exclaims. ‘Mommy, he just said a bad word’, Melissa says. To this, Castle responds: ‘He’s entitled to right now, sweetie’, then adds, ‘Bishop, nail the fucker!’

Where Dacascos and Moss evidence warmth in their portayals of Bishop and Castle, Tony Todd savours his role as the film’s chief heavy, mocking his victims (‘Ouch’, he smiles as the bullet from his rifle kills both Trent and Trent’s bodyguard) and delighting in muttering to himself as he works (‘So, you’re having a good day? Well, that’s about to change’, he says as he watches Trent’s jet land). The film contains some bone-crunching violence that it’s hard to imagine the BBFC passing uncut in 1997 (though apparently they did). The highlight in this regard is an extended action setpiece in which Castle arranges a SWAT team to descend on the suburban house in which Sherwood and his gang are hiding. The SWAT team begin their raid but are ambushed by Sherwood and his associates. A long gun battle ensues, the impact of bullets hitting bodies communicated through slow-motion and the use of squibs that betrays the influence of Sam Peckinpah (or perhaps Peckinpah via John Woo). Sherwood escapes through a tunnel under the house. Bishop and Castle follow. The tunnel leads to a stadium where a female ice hockey team are practising. Sherwood and an accomplice take a number of the players hostage; Bishop and Castle attempt to free them, Dacascos executing a slide across the ice whilst firing a handgun. It’s a spectacular sequence – exciting, well-shot and very tightly-edited – with the brand of mostly authentic violence, delivered in a very unpretentious manner, that characterised low budget action films of the era (and seems even more rare in modern cinema).    The film runs for 99:27 and would seem to be uncut. (The uncut UK VHS release from BMG had a very similar running time of 98:57 mins - but this was owing to the tape being a poor standards conversion from an NTSC source.)

Video

Sabotage went straight-to-video in the UK, being released on VHS by BMG Video in 1997. Since the advent of the DVD format, Sabotage has been a fairly difficult film to see, though it did get a DVD release in a number of countries outside the US and the UK. These DVD releases tended to present the film in a fullframe (open-matte) aspect ratio and were also barely improved over the film’s VHS presentations. Sabotage went straight-to-video in the UK, being released on VHS by BMG Video in 1997. Since the advent of the DVD format, Sabotage has been a fairly difficult film to see, though it did get a DVD release in a number of countries outside the US and the UK. These DVD releases tended to present the film in a fullframe (open-matte) aspect ratio and were also barely improved over the film’s VHS presentations.

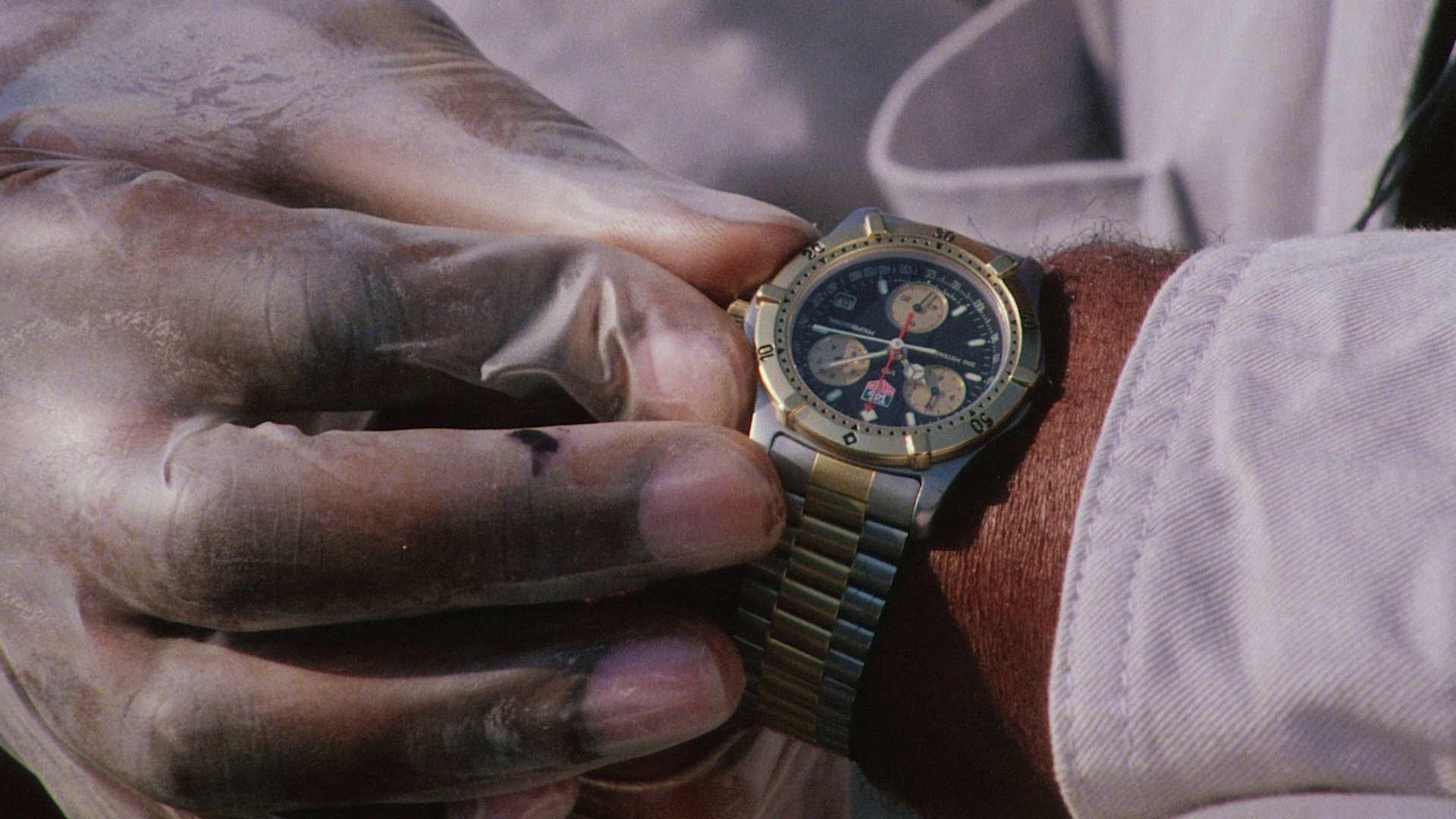

This Blu-ray release goes some way to correcting this, presenting Sabotage in the 1.78:1 ratio – which seems fine with the material, though there’s just enough headroom to suggest that the film was most likely shot with the slightly wider 1.85:1 ratio in mind. There’s a good level of detail present within the image, which is certainly above that which one would expect from a DVD, but there is also some evidence of noise reduction software having been applied to it – not too extensively, however, as to impact on one’s enjoyment of the film, as some fine detail can be deduced (eg, in facial close-ups – see some of the larger screengrabs below). The natural grain structure of 35mm film is present but seems a little muted. Shots drift in and out of focus at times, with the focus puller being a little slow on the uptake – which of course is a consequence of the production of the film, rather than this presentation. There’s also a brief moment of judder/gate weave at 21 minutes into the picture, but that’s a very minor issue. Colour consistency is strong. On the other hand, contrast is unnaturally boosted, with crushed blacks in a number of scenes (especially those shot in low-light) and the highlights sometimes seeming ‘clipped’ in a way that makes the film (shot on 35mm) seem to evidence the tighter dynamic range of something shot on digital video. (In this regard, the presentation has the characteristics of a presentation sourced from a high contrast 35mm print, and I wonder if that is indeed the case.) That said, there seems to be evidence that the film was shot with the flat lighting of many low budget action films of the mid/late-1990s that were made for video and/or cable distribution, and the boosted contrast may have been introduced to the master to mitigate this. The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film itself takes up approximately 15Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc. The encode handles the material fine, with no issues to speak of.    NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo track. This track evidences a powerful sense of range and is truly ‘punchy’ when it needs to be – from the opening warzone footage, with its explosions and helicopters flying overhead, to the shot of Trent’s jet passing over the camera. Sadly, no subtitles are included.

Extras

None.

Overall

Perhaps surprisingly (at least, for some viewers), Sabotage is a very good little film: Tony Todd’s performance as the villain is delivered with gusto, and Dacascos and Moss are pleasant, charismatic leads. The film is graced with an intelligent script, and embodies the best qualities of lower-budget action films of the era: a modest sense of scale, an intimate narrative (in this instance, graced with a strong sense of paranoia and distrust of authority) and some solid, efficiently handled action set-pieces – without the overwrought, overstylised approach of the bigger budget Hollywood action films. There’s a touch of Peckinpah (or perhaps John Woo) in the editing of these moments of action too, with slow-motion footage edited together across different planes of action. Just two things stand out of place: the use of ridiculous and completely unrealistic video enhancement software (that was an equally ridiculous and unrealistic addition to the bag of tricks used in the CBS television show CSI, 2000-15, a few years later) to reveal the identity of Sherwood in footage culled from an ATM’s security machine; and the apparently computer-generated slow-motion shots following the trajectory of the bullets fired out of Sherwood’s high-powered sniper rifle. The latter is a technique that in all likelihood was ‘borrowed’ from Ringo Lam’s 1992 Hong Kong action film Full Contact, where considering the other excesses of Lam’s style it didn’t seem as out of place as it does here. (However, even this seemingly 'gimmicky' technique has a decent pay-off at the climax of Sabotage.) Perhaps surprisingly (at least, for some viewers), Sabotage is a very good little film: Tony Todd’s performance as the villain is delivered with gusto, and Dacascos and Moss are pleasant, charismatic leads. The film is graced with an intelligent script, and embodies the best qualities of lower-budget action films of the era: a modest sense of scale, an intimate narrative (in this instance, graced with a strong sense of paranoia and distrust of authority) and some solid, efficiently handled action set-pieces – without the overwrought, overstylised approach of the bigger budget Hollywood action films. There’s a touch of Peckinpah (or perhaps John Woo) in the editing of these moments of action too, with slow-motion footage edited together across different planes of action. Just two things stand out of place: the use of ridiculous and completely unrealistic video enhancement software (that was an equally ridiculous and unrealistic addition to the bag of tricks used in the CBS television show CSI, 2000-15, a few years later) to reveal the identity of Sherwood in footage culled from an ATM’s security machine; and the apparently computer-generated slow-motion shots following the trajectory of the bullets fired out of Sherwood’s high-powered sniper rifle. The latter is a technique that in all likelihood was ‘borrowed’ from Ringo Lam’s 1992 Hong Kong action film Full Contact, where considering the other excesses of Lam’s style it didn’t seem as out of place as it does here. (However, even this seemingly 'gimmicky' technique has a decent pay-off at the climax of Sabotage.)

Contrast is boosted in this presentation, resulting in some noticeably ‘crushed’ blacks. That said, it’s still head and shoulders (and probably a really big gun) above the film’s previous home video incarnations, and at the price point that 101 Films’ releases usually go for, is pretty much an essential purchase for fans of mid-1990s DTV action pictures. As with many of the lower budget action films of the era, there’s a slightly film noir-ish vibe to the picture, and on the whole the film itself is a delight, with an unpretentious script that has something to say and plenty of charisma with which to say it. It’s certainly one of the best action films Dacascos appeared in during this stage of his career, and deserves to be more widely seen than it has been. References: Cettl, Robert, 2009: Terrorism in American Cinema: An Analytical Filmography, 1960-2008. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc Lott, M Ray, 2004: The American Martial Arts Film. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc

|

|||||

|