|

|

Shopping (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Fabulous Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Shopping (Paul W S Anderson, 1994) Shopping (Paul W S Anderson, 1994)

The outcry and controversy surrounding Paul W S Anderson’s 1994 debut feature Shopping is hard to imagine now, only a little over 20 years after the film’s original release. Caught up in the debates surrounding violence in the cinema and on home video that also led to Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) having its home video release delayed for two years, Shopping was withheld a certificate for several months whilst the BBFC reflected on whether or not the film glamourised joyriding/‘TWOCing’ (‘Taking Without Owner’s Consent’) and ram-raiding. Vehicular theft was of course not a new phenomenon, but its rebranding as ‘joyriding’ (ie, the stealing of a car simply for the ‘joy’, or adrenaline thrill, of driving it fast and being pursued by the police, then often finishing the evening’s entertainment by torching said vehicle) seemed, in the eyes of the media at least, to increase its popularity amongst disenfranchised youth within the provincial towns and cities of quaint old England. Alongside this was a seemingly more modern crime, that of ram-raiding: driving a vehicle through the doors or windows of a shop in order to steal the stock. Shopping focused on both. In many ways, Shopping seems like a Litmus test of the times, with its focus on joyriding, ram-raiding, vague references to the Troubles, Star Wars toys, skateboarding, audio cassettes, rampant gangs who own the council estates on which they live, smooth-faced posh actor Jude Law playing a rough-around-the-edges youth from one of said council estates, underground nightclubs blaring out house music, posh actor Sadie Frost playing a rough-around-the-edges lass from Belfast who hangs out on said council estates, and the two Seans (Bean and Pertwee). The film takes place in the 1990s although seems to be set slightly in the future (which, of course, is now in the past).  Shopping focuses on Billy (Law), who is released from prison having served a short sentence for joyriding. Billy is an adrenaline junkie who steals cars for the thrill. He is met on his release by his friend Jo (Frost), who is originally from Belfast. Jo and Billy return to the estate on which they live, where Billy meets up with his other friends Be Bop (Fraser James) and Monkey (Danny Newman). However, Billy discovers that his position at the top of the food chain on the estate has been stolen during his absence by Tommy (Sean Pertwee). Where Billy steals cars for kicks, Tommy has turned this pastime into a business, organising ram-raids in order to acquire stock and then selling it on to Venning (Sean Bean). Naturally, Billy and Tommy come into conflict. Meanwhile, Jo seems to offer Billy the chance to escape from his life on the estate and settle down – but will Billy seize the opportunity that has been offered to him? Shopping focuses on Billy (Law), who is released from prison having served a short sentence for joyriding. Billy is an adrenaline junkie who steals cars for the thrill. He is met on his release by his friend Jo (Frost), who is originally from Belfast. Jo and Billy return to the estate on which they live, where Billy meets up with his other friends Be Bop (Fraser James) and Monkey (Danny Newman). However, Billy discovers that his position at the top of the food chain on the estate has been stolen during his absence by Tommy (Sean Pertwee). Where Billy steals cars for kicks, Tommy has turned this pastime into a business, organising ram-raids in order to acquire stock and then selling it on to Venning (Sean Bean). Naturally, Billy and Tommy come into conflict. Meanwhile, Jo seems to offer Billy the chance to escape from his life on the estate and settle down – but will Billy seize the opportunity that has been offered to him?

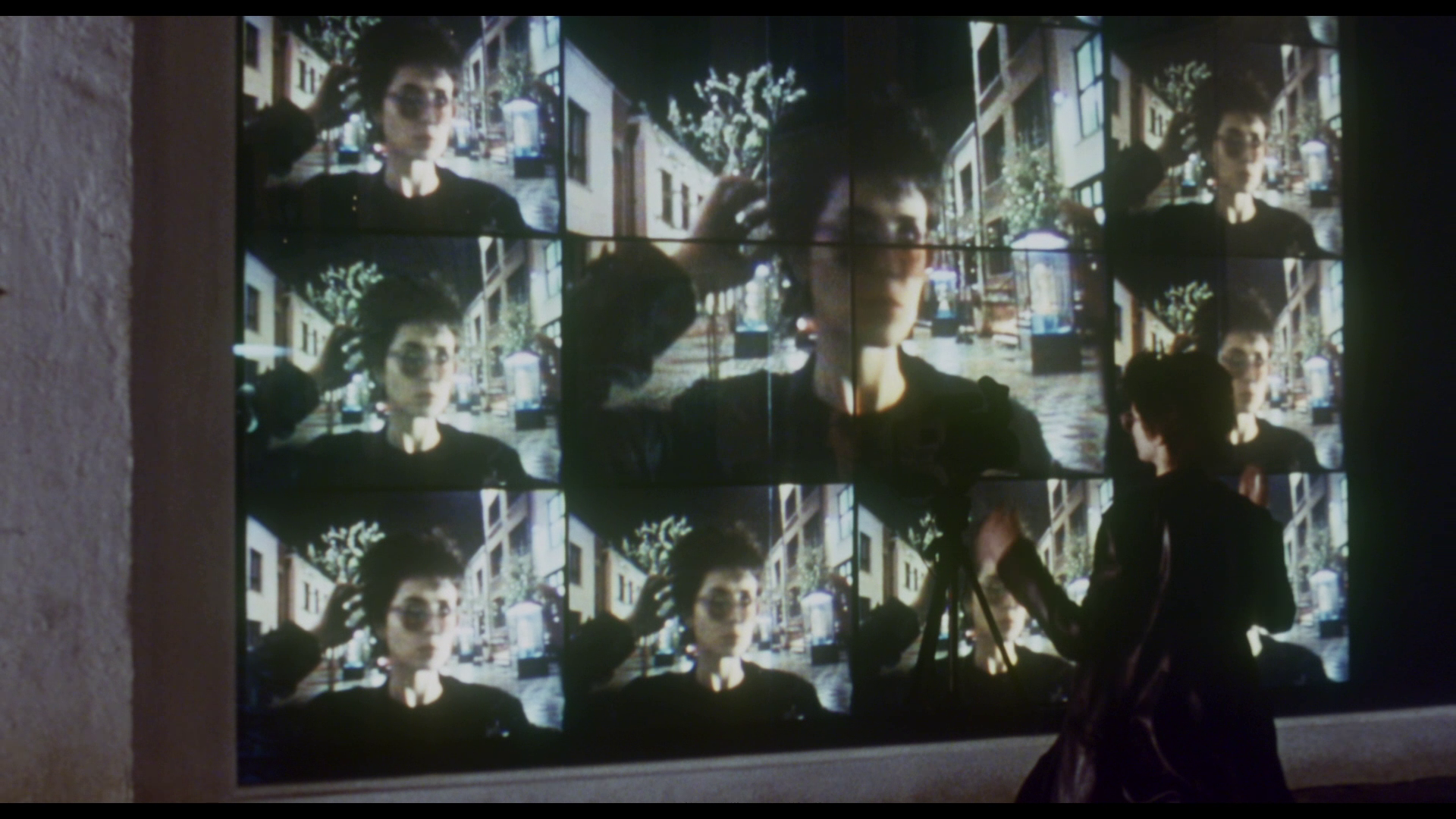

Like a number of British films of the early 1990s (eg, Danny Cannon’s The Young Americans, 1993), Shopping attempted to steer British cinema away from the staid Merchant-Ivory-style costume dramas with which it had become associated by looking towards American depictions of the urban space as one dominated by violence (for example, films like Walter Hill’s The Warriors, 1979). Two years later, it would be followed by Danny Boyle’s equally controversial adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting. In its depiction of amoral, utterly disaffected ‘yoof’, Shopping also looked towards Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1972), itself set slightly in the future (in relation to its production) and featuring unrepentant youth gangs rampaging through an English city. However, in Billy’s return to the estate only to find that his ‘crown’ has effectively been usurped by Tommy – who has transformed Billy’s ‘thrill’ into a lucrative business – the film also seems to allude (intentionally or not) to a more classical model: the relationship between Richard the Lionheart and King John.  Although clearly shot in London, Shopping seems to take place in a nameless provincial city. Tommy’s hideout is a seemingly derelict building, the Plaza, the rundown exterior hiding the slot machines and hive of activity inside (a sign outside the building declares, ‘If it’s Plaza, it’s pleasure’ – an index of the hedonistic lifestyles of the film’s characters, whose every action seems motivated by their own delight). CCTV cameras are everywhere: at one point, Jo stands in front of a bank of television monitors in the window of a department store, the monitors reflecting her own image – in multiple quantities. The streets are dominated by shrines to dead joyriders, killed getting their kicks, and the burnt-out shells of cars. In one scene, wandering through the streets with Jo, Monkey refers to the torched vehicles and asserts, ‘Oh, man. Look at this’. ‘Yeah, wonderful, Monkey. Just like home’, Jo responds without a trace of irony (Sadie Frost’s accent, best described as ‘wobbly’, is Belfast-by-way-of-Cardiff). Although clearly shot in London, Shopping seems to take place in a nameless provincial city. Tommy’s hideout is a seemingly derelict building, the Plaza, the rundown exterior hiding the slot machines and hive of activity inside (a sign outside the building declares, ‘If it’s Plaza, it’s pleasure’ – an index of the hedonistic lifestyles of the film’s characters, whose every action seems motivated by their own delight). CCTV cameras are everywhere: at one point, Jo stands in front of a bank of television monitors in the window of a department store, the monitors reflecting her own image – in multiple quantities. The streets are dominated by shrines to dead joyriders, killed getting their kicks, and the burnt-out shells of cars. In one scene, wandering through the streets with Jo, Monkey refers to the torched vehicles and asserts, ‘Oh, man. Look at this’. ‘Yeah, wonderful, Monkey. Just like home’, Jo responds without a trace of irony (Sadie Frost’s accent, best described as ‘wobbly’, is Belfast-by-way-of-Cardiff).

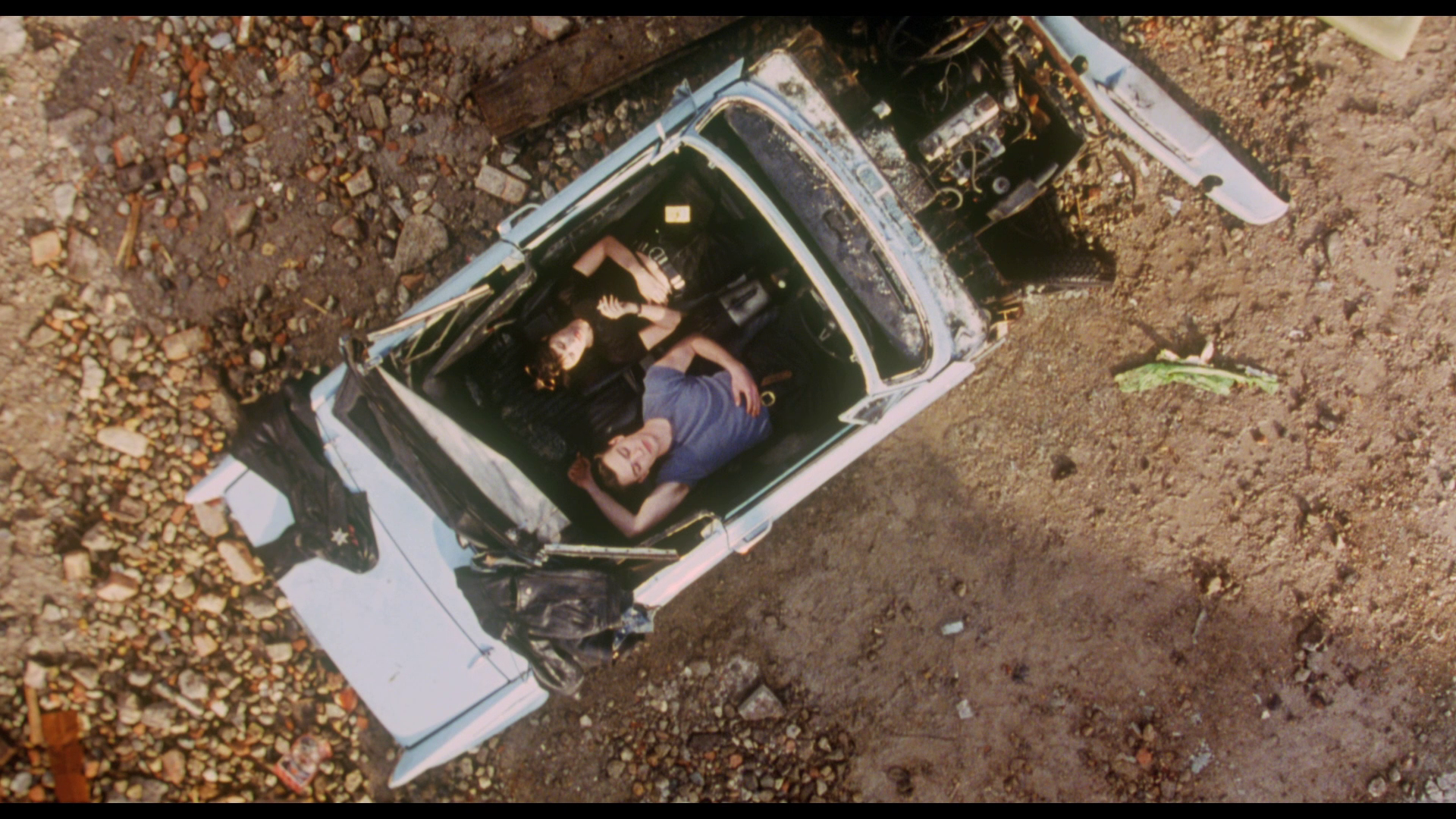

Jo’s past in Belfast is alluded to when she tells Billy of a friend of hers who, caught stealing cars, was kneecapped with a shotgun – a common technique used by the paramilitary forces in Belfast to punish transgressors. This punishment, alluded to verbally but not shown on screen, is juxtaposed with the impotence of the British police officers – mostly depicted as knuckleheads with potty mouths who are themselves the victims of the street gangs. Without shame, in one sequence Tommy’s gang roll up to the local police station and trash the vehicles there; in another sequence, Billy and Jo lead the police on a car chase which ends in the estate, where the police are ambushed by an enormous group of young people who firebomb the police cars. (The depiction of British police as foul-mouthed and essentially idiotic thugs was perhaps another reason for the BBFC’s delay in giving the film a certificate – and the refusal of a number of cinemas to show the picture.) The film opens with Jo meeting Billy after his release from the prison. Close-up shots of Billy in his cell, then a long shot of him being led down a long corridor, are followed by a brief scene in which Billy meets with high-ranking police officer Conway (Jonathan Pryce). Conway asks Billy, ‘What’s prison taught you, Billy?’ The unrepentant Billy answers, ‘Don’t get caught’. Outside, Billy is collected by Jo. This opening sequence seems to allude to the opening scenes of Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972), in which Steve McQueen’s Doc McCoy is released from prison after a parole hearing and collected by his wife Carol (Ali McGraw). In the car, Billy opens a packet of Loveheart sweets and gives Jo one which reads: ‘Be Mine’. ‘Romantic crap’, Jo says.  The opening sequence seems to suggest that Billy and Jo are lovers, though this isn’t the case. The pair are close friends, arguably in love with one another, but without a physical relationship. In a nightclub, Be Bop comments on Billy and Jo’s relationship, asking Jo ‘What’s the matter with you two? You don’t like fucking?’ To this, Jo replies, ‘That’s none of your business. Besides, if you don’t get humped, you don’t get dumped’. The film’s depiction of sexuality is clearly informed by the post-AIDS panics about sex that took place in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Hiding from Tommy’s gang in an abandoned train graveyard, Jo finally makes a physical advance towards Billy, kissing him on the lips. For his part, Billy turns his head away. ‘This is the 90s’, Billy declares matter-of-factly, ‘Sex isn’t safe anymore’. The opening sequence seems to suggest that Billy and Jo are lovers, though this isn’t the case. The pair are close friends, arguably in love with one another, but without a physical relationship. In a nightclub, Be Bop comments on Billy and Jo’s relationship, asking Jo ‘What’s the matter with you two? You don’t like fucking?’ To this, Jo replies, ‘That’s none of your business. Besides, if you don’t get humped, you don’t get dumped’. The film’s depiction of sexuality is clearly informed by the post-AIDS panics about sex that took place in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Hiding from Tommy’s gang in an abandoned train graveyard, Jo finally makes a physical advance towards Billy, kissing him on the lips. For his part, Billy turns his head away. ‘This is the 90s’, Billy declares matter-of-factly, ‘Sex isn’t safe anymore’.

Alongside this, there is a none-too-subtle homoeroticism to the film. Billy’s insistent denial of a sexual relationship with the tomboyish Jo (clad in androgynous short hair, trenchcoat and trousers), combined with Law’s slightly effeminate – and frequently shirtless – performance, suggests a concealed sexuality on the part of Billy. (Billy’s sexuality seems to be sublimated onto the thrill he associates with TWOCing.) ‘What side of the road are you on, Billy?’, Jo asks at one point. ‘Both’, is Billy’s answer. Later, Tommy and Venning face off against one another in a business deal, the two characters moving closer together in a scene in which they are invading one another’s personal space as a form of intimidation – but they almost seem ready to kiss (in fact, this appears to be on the minds of Sean Pertwee and Sean Bean, who at one point during this scene almost seem to partake in the popular theatrical pastime of ‘corpsing’). Later, tiring of Tommy and Billy’s obsession with one another, Jo declares, ‘I don’t know why you and Tommy don’t just get ‘em out, see who’s got the biggest dick and save us all the trouble’. Both Billy and Jo are young. However, where Jo seems to dream of settling down, Billy sees little future for himself. When asked by Bev (Marianne Faithful), ‘Why don’t you grow up?’, Billy responds with his own question: ‘And do what?’ Later, Jo suggests to Billy that she’s ready to settle down, telling him ‘I’m 22, I’m an old woman’. Jo’s childlike nature is emphasised by her obsession with a GameGear-type handheld games console that they find in the BMW the pair steal near the beginning of the film. For many subsequent sequences, Jo is shown playing the game – which in the film is named ‘Crazy Car’ but looks like the 1986 Sega game Outrun – during moments in which she and Billy are pursued by the police, her obsessive gaze at the screen of the handheld console suggesting nonchalance and solipsism. The game, we are told in the dialogue, requires the player to score points by ramming other vehicles off the road. Shopping rather suggests that this Carmageddon-type violence (three years before the release of Carmageddon and its brethren Grand Theft Auto) partly inspires, or at least legitimates the amorality of the film’s young joyriders and ram-raiders: it’s a curiously conservative argument from a film which itself has been claimed to glamourise such activity, suggesting the medium of cinema criticising the ‘new kid on the block’, the then-relatively new medium of video games. The film is uncut and runs for 106:36 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, this presentation of Shopping is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc, this presentation of Shopping is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec.

The film, presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, opens with the old Polygram logo and looks to be from an aged videotape-era master. The promotional material suggests that the release uses a ‘brand new fully restored hi definition master’, but as with the recent release of Killing Zoe this clearly isn’t the case. Perhaps there has been some kind of administrative mix-up, as this presentation displays the ‘clipped’, flattened contrast of VHS era masters, with highlights being blown out and detail lost in the shadows. (This has a concomitant effect on the skin tones, with many of the actors looking sickly throughout.) In fact, there's little to no difference between the Blu-ray release and Fabulous Films' accompanying DVD release of the title (see the comparison screengrabs below). Although much of the film was shot with diffused light generated by smoke used on the set, this presentation has an unnaturally soft, filtered look. Detail is lacking, and there’s an absence of film grain and smoothness to the textures that suggests heavy application of noise reduction. Some scenes fair better than others, but on the whole this has the clipped dynamic range and ‘flatness’ that characterised the film’s VHS release. There are also a handful of digital glitches, seemingly sourced from the master rather than the encode (for example, there’s one at 49:28 which completely obliterates Jude Law’s face for a fraction of a second).   NB. Some larger screengrabs are included below.

Audio

Audio fares much better. The film is presented with a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track and a DTS-HD MA 2.0 stereo track. Both of these are clean and clear, though dialogue is sometimes lost in the mix in both of them – which seems to be true to the original sound design (I remember some of the dialogue being difficult to discern when I saw the film at the cinema). Both tracks have a good sense of range, with the 2.0 track displaying a particularly ‘punchy’ use of bass. The 5.1 track has added sound separation but the 2.0 track is altogether more impactful. No subtitles are provided.

Extras

The disc includes: - Cast and crew interviews (7:09). These interviews, conducted during the production of the film, feature Anderson and the principal cast talking about the film and their roles in its creation. - B-Roll (6:12). This is ‘B’ roll footage from the production of the picture, offering a behind-the-scenes glimpse of its production. - Trailer (1:40).

Overall

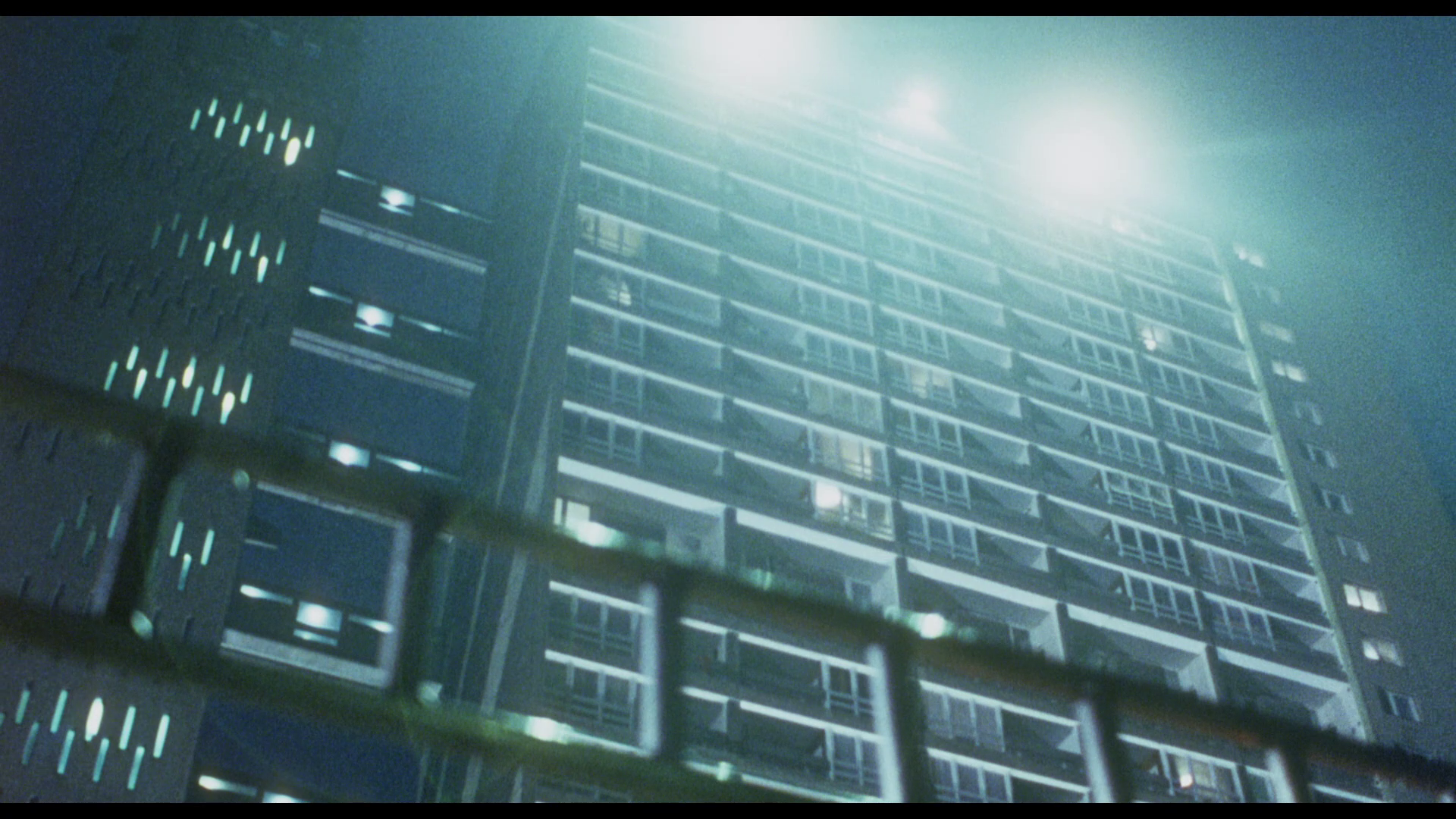

Watching Shopping is an odd experience, remembered by many as the film which brought Jude Law and Sadie Frost together. Jude Law has charisma but isn’t particularly convincing as Billy. It’s a brash, loud film (Sadie Frost’s incessant shouting was incredibly grating in the cinema and is arguably still as annoying on home video). What works well, however, are the film’s post-industrial landscapes: the shots of refineries which open the film, and the inhuman tower blocks that dot the urban landscape: in this sense, the film shares its vision of the near-future of Britain with Tony Maylam’s Split Second (1992). Watching Shopping is an odd experience, remembered by many as the film which brought Jude Law and Sadie Frost together. Jude Law has charisma but isn’t particularly convincing as Billy. It’s a brash, loud film (Sadie Frost’s incessant shouting was incredibly grating in the cinema and is arguably still as annoying on home video). What works well, however, are the film’s post-industrial landscapes: the shots of refineries which open the film, and the inhuman tower blocks that dot the urban landscape: in this sense, the film shares its vision of the near-future of Britain with Tony Maylam’s Split Second (1992).

Shopping comments on a Britain which is populated by disaffected, disenfranchised youth who see no future for themselves and function solely for their own pleasure. But on the other hand, they’re curiously sexless – and in fact seem afraid of sexuality, sublimating it onto TWOCing and gorilla-like chest beating. The true villain of the piece is Venning, the capitalist, and the lure of the shrines to consumerism that, given the hopelessness of the lives of the film’s young people, seem out of reach for many. It’s also a society that seems to be thoroughly Americanised. In the nightclubs, the young people drink American beer. ‘King of beers’, Billy declares. ‘Prince of piss’, Jo responds (displaying infinite wisdom and good taste), ‘Now Guinness, there’s a drink’. Later, Conway confronts Billy in his home. ‘I know my rights’, Billy tells Conway, ‘I watch L A Law’. ‘Is that supposed to be funny?’, Conway asks. ‘No’, Billy says, ‘More comedy-drama, you know what I mean?’ As a whole, the film offers a curious snapshot of the anxieties of Britain in the early 1990s – and in many ways (eg, its association of the videogame Jo plays with the aggression of Billy and his kind) seems deeply conservative. This conflicted approach to the material is something which has dogged many of Paul W S Anderson’s subsequent films. Ironically, a number of which, Mortal Kombat (1995) and the Resident Evil films, are videogame adaptations; and another of which, the 2008 remake of Death Race, is a Carmageddon-style romp. There’s a strong case to be made for Soldier (1998) and Event Horizon (1997) as the best films of Anderson’s career, by a long shot, but Shopping certainly started that career with a bang of controversy. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray release is sadly lacking – which is a shame, as I’ve sampled some of Fabulous Films’ other upcoming Blu-ray releases and they’re a distinct improvement on this. One can only assume that the company have been saddled with a poor, aged master and an impending deadline. The master itself displays the characteristics of VHS era masters, including ‘clipped’ contrast and plentiful noise reduction resulting in a very ‘flat’, smooth image. However, the sound is much better, with both the lossless 5.1 and 2.0 tracks being clear throughout. Fabulous Films' DVD:

Fabulous Films' Blu-ray:

Fabulous Films' DVD:

Fabulous Films' Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|