|

|

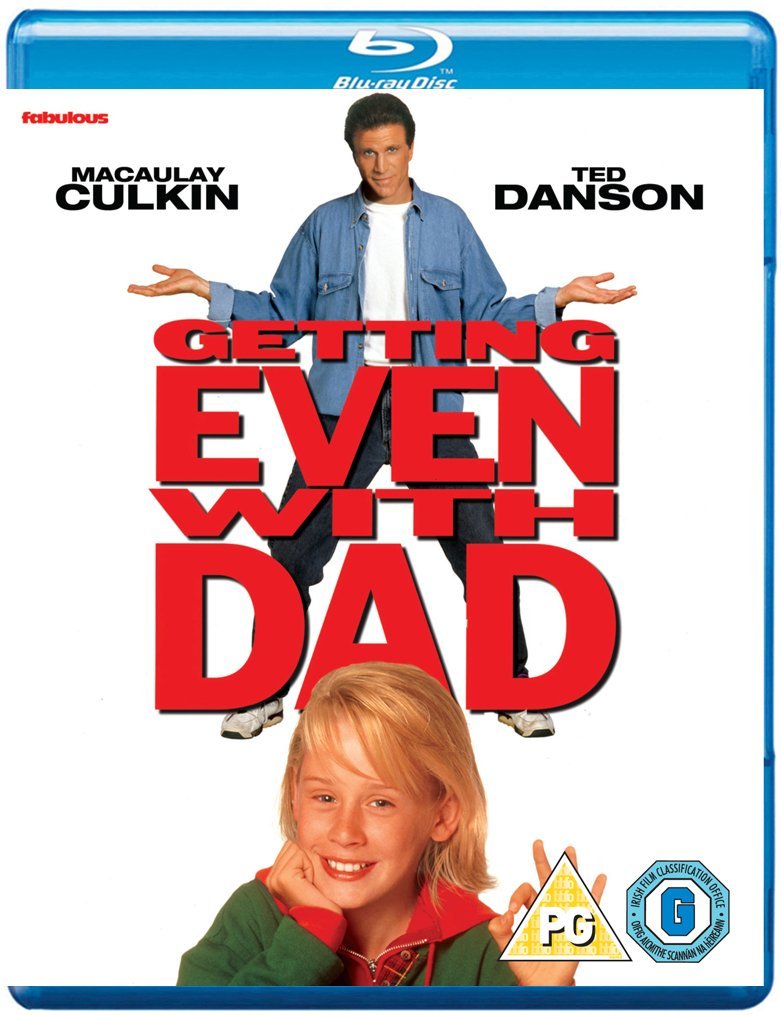

Getting Even with Dad (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Fabulous Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd August 2015). |

|

The Film

Getting Even with Dad (Howard Deutch, 1994) Getting Even with Dad (Howard Deutch, 1994)

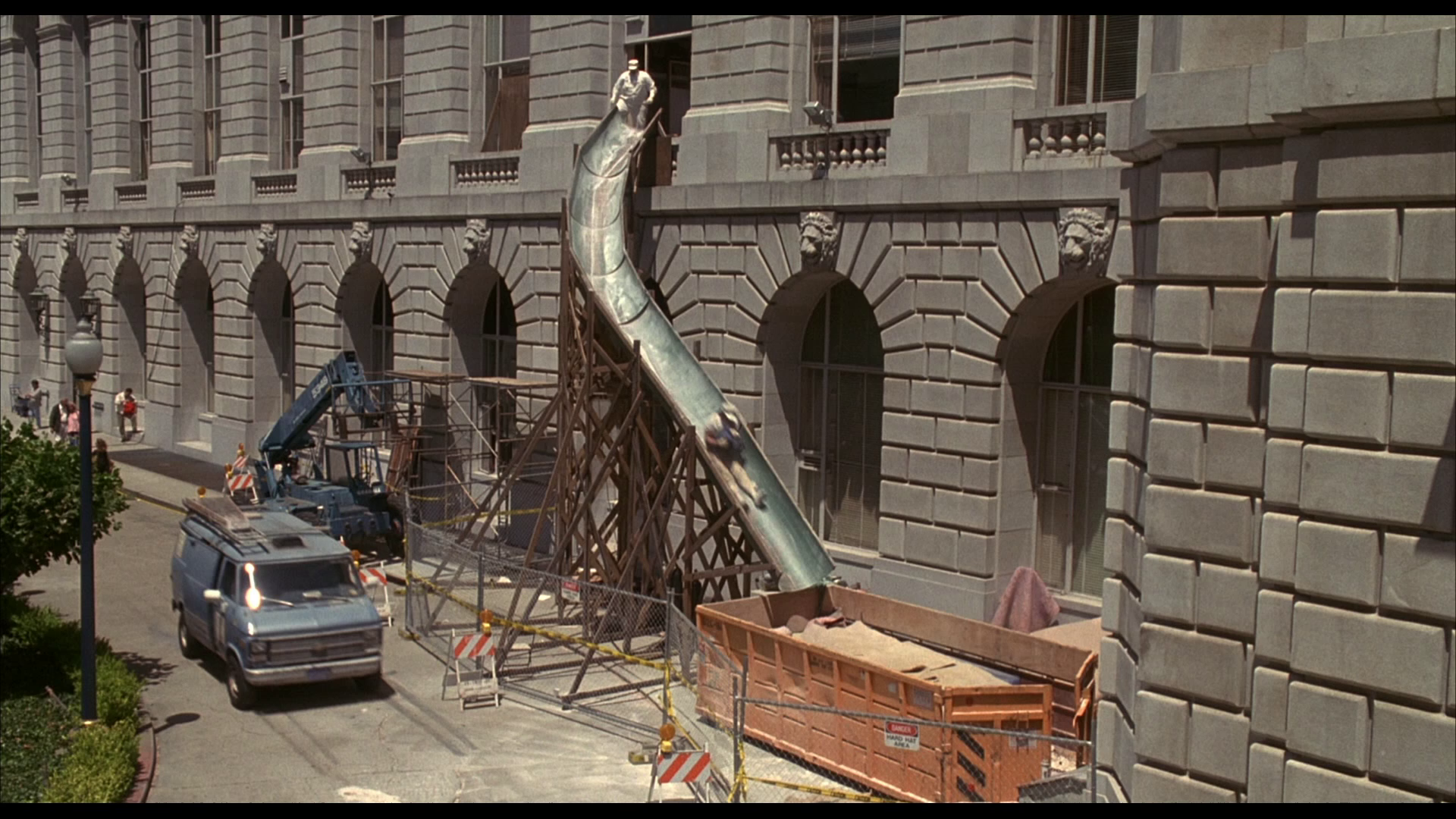

Essentially one of a number of films produced during the 1990s to capitalise on the phenomenal success of the John Hughes-scripted Home Alone (Chris Columbus, 1990) and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (Chris Columbus, 1992), Howard Deutch’s Getting Even with Dad (1994) features Macaulay Culkin in a similar ‘lost child’ role to that he played in Home Alone. The previous year’s The Good Son (Joseph Ruben, 1993), an adaptation of Ian McEwan’s novel The Child in Time, had starred Culkin in a disturbing narrative – featuring Culkin playing a child psychopath – which in many ways is the dark mirror image of the Home Alone pictures. However, Getting Even with Dad, produced the year after, is a bittersweet examination of the relationship between child and parent that for the most part emulates the ‘safe’ formula of slapstick and ‘angelic brattiness’ in Culkin’s performance that characterised the Home Alone films (Dubner, 1993: 56). At the time, the notoriety surrounding the release of The Good Son in the UK – where the film’s video release was delayed owing to the fallout from the murder of James Bulger – seemed to hang over Culkin’s subsequent films, including this one, making the characters he played seem somehow more sinister by their intertextual relationship with The Good Son – these characters’ conniving manipulations of their elders seeming more Machiavellian than cute or ‘angelically bratty’.  In Getting Even with Dad, Culkin plays Tim Gleason, a boy who is sent by his newlywed aunt Kitty (Kathleen Wilhoite) to live with his father (Kitty’s brother) Ray (Ted Danson). Ray is an ex-con who is working in a bakery as a decorator of cakes. Ray wants to go straight, but in order to do so he’s planning one last job with his long-term accomplices Bobby (Saul Rubinek) and Carl (Gailard Sartain). Ray, Bobby and Carl plan to steal some rare, valuable coins which have been transferred to San Francisco’s Professional Coin Grading Service for valuation following the death of their owner, an elderly lady whose possessions, in the absence of any close family, have become the property of the US government. Ray reasons that as the coins are now in the possession of the US government, the theft of them is a ‘victimless’ crime and, with his share of the score, he intends to buy the bakery in which he works – thus ensuring a future for himself within legitimate society. In Getting Even with Dad, Culkin plays Tim Gleason, a boy who is sent by his newlywed aunt Kitty (Kathleen Wilhoite) to live with his father (Kitty’s brother) Ray (Ted Danson). Ray is an ex-con who is working in a bakery as a decorator of cakes. Ray wants to go straight, but in order to do so he’s planning one last job with his long-term accomplices Bobby (Saul Rubinek) and Carl (Gailard Sartain). Ray, Bobby and Carl plan to steal some rare, valuable coins which have been transferred to San Francisco’s Professional Coin Grading Service for valuation following the death of their owner, an elderly lady whose possessions, in the absence of any close family, have become the property of the US government. Ray reasons that as the coins are now in the possession of the US government, the theft of them is a ‘victimless’ crime and, with his share of the score, he intends to buy the bakery in which he works – thus ensuring a future for himself within legitimate society.

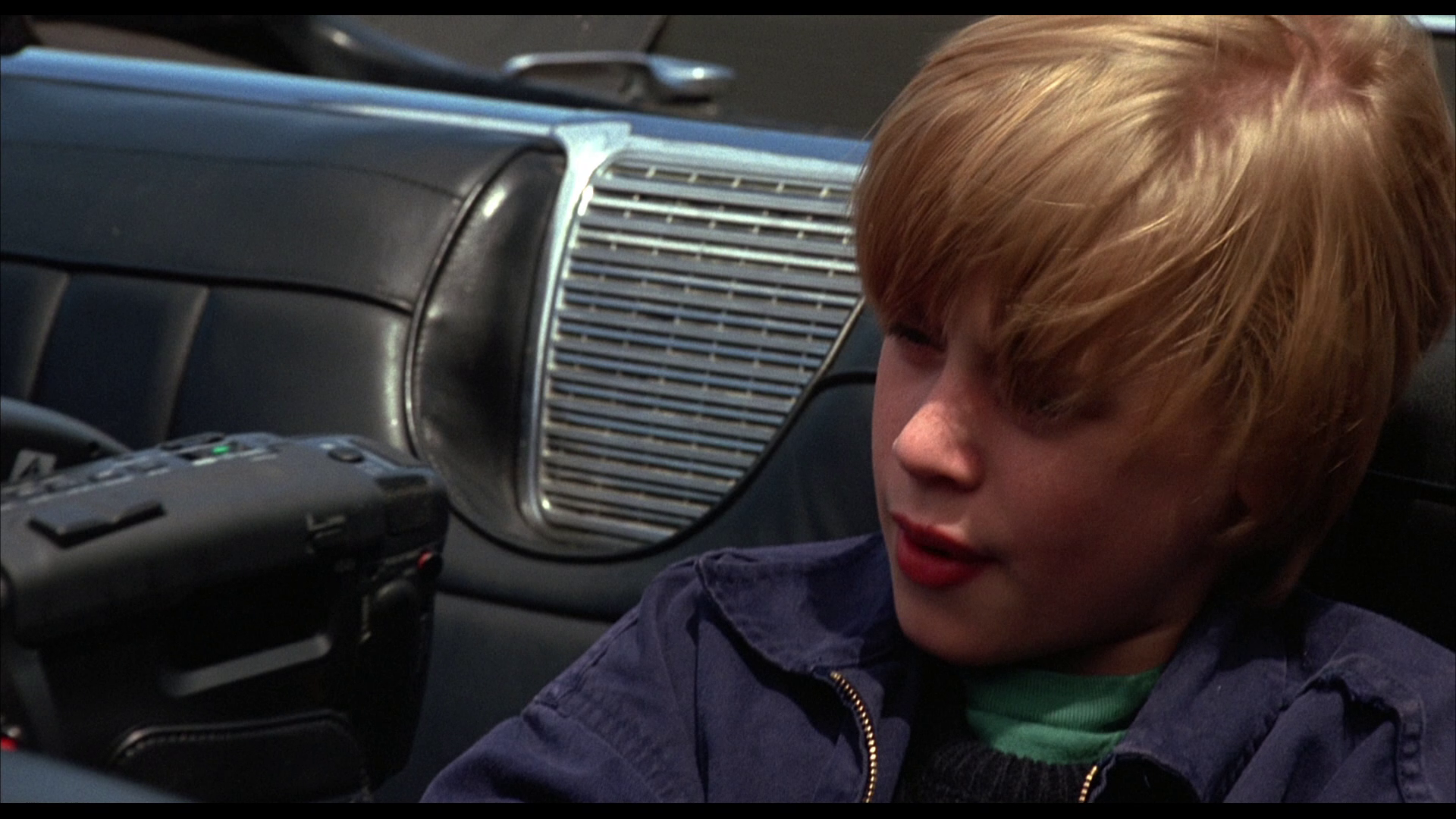

However, when Ray’s crew have stolen the coins, Tim becomes aware of their plan. He discovers the spot in which they have hidden their swag and, behind their backs, hides the coins in another location. With the promise that he will reveal the location in which he has hidden the coins, Tim blackmails Ray into acting like a ‘real’ father, taking him out to various locations (ice skating, a theme park, fishing) and bonding with him. Meanwhile, Bobby becomes increasingly resentful of Tim’s plan and threatens the child with violence, whilst unbeknownst to Ray and the others, the police – including Detective Theresa Walsh (Glenne Headly) – have already identified them as the thieves and are keeping them under surveillance. Things become increasingly complicated when Theresa begins to fall for Ray. Getting Even with Dad came at the point at which the Macaulay Culkin ‘bubble’ began to burst – with this film and the same year’s Ri¢hie Ri¢h (Donald Petrie) and The Pagemaster (Maurice Hunt & Joe Johnston) struggling to emulate the commercial success of Home Alone. Culkin would subsequently be absent from cinema screens for almost a decade, returning to feature films as an adult actor with roles (for example, as murderer Michael Alig in Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato’s Party Monster, 2003) that seemed intended to distance Culkin from the ‘cute’ persona that had been cultivated around most of his big screen roles in his youth.  The connections with Home Alone come thick and fast, from the use of retro hits on the soundtrack (‘Money (That’s What I Want)’), over the opening titles) to the technology savvy nature of Culkin’s character. Where in Home Alone and Home Alone 2, Culkin used videotape recordings of imagined 1930s gangster film Angels with Filthy Souls and its sequel Angels with Even Filthier Souls to ward off the adults who threatened him, in Getting Even with Dad Tim uses a home video camera at several points in the film, and it is one of Tim’s video recordings that reveals to Ray that they are under surveillance by Theresa. (A number of sequences feature monochrome footage shot from the perspective of Tim's video camera.) Meanwhile, there’s much emphasis on outrageous slapstick and an extended musical sequence in which, visiting a theme park, Tim enters a ‘Make Your Own Music Video’ booth and mimes and dances to The Contours’ 1962 hit ‘Do You Love Me?’ – his performance so infectious that it encourages Ray’s associates to join in. The connections with Home Alone come thick and fast, from the use of retro hits on the soundtrack (‘Money (That’s What I Want)’), over the opening titles) to the technology savvy nature of Culkin’s character. Where in Home Alone and Home Alone 2, Culkin used videotape recordings of imagined 1930s gangster film Angels with Filthy Souls and its sequel Angels with Even Filthier Souls to ward off the adults who threatened him, in Getting Even with Dad Tim uses a home video camera at several points in the film, and it is one of Tim’s video recordings that reveals to Ray that they are under surveillance by Theresa. (A number of sequences feature monochrome footage shot from the perspective of Tim's video camera.) Meanwhile, there’s much emphasis on outrageous slapstick and an extended musical sequence in which, visiting a theme park, Tim enters a ‘Make Your Own Music Video’ booth and mimes and dances to The Contours’ 1962 hit ‘Do You Love Me?’ – his performance so infectious that it encourages Ray’s associates to join in.

At the time, especially given the fact that the US release was timed to coincide with Father’s Day, the film seemed to consolidate Danson’s association in cinema as a reluctant father (which seemed an extension of his role as responsibility-avoiding lothario Sam Malone in Cheers, 1982-93): Danson had played a similar part, of course, in Three Men and a Baby (Leonard Nimoy, 1987) and its sequel Three Men and a Little Lady (Emile Ardolino, 1990), and in Dad (Gary David Goldberg, 1989). The film is essentially about the ‘education’ of the character of Ray, who as the narrative progresses matures from a position of the avoidance of responsibility to a profound love (and need) for his son. As the film begins, Ray is shown with Carl and Bobby, who question Ray about his relationship with his current paramour Nadine. Nadine has presented Ray with a houseplant. Carl notes Ray’s refusal to answer a telephone call that is presumed to come from Nadine. ‘I thought you liked Nadine’, Carl observes. ‘I did’, Ray says, ‘till she got me that stupid plant. Believe me, when a lady gives you a plant it’s her way of testing you, like if you can take care of it it’s a sign to her that she can move the relationship to the next level. Trust me, when a woman gives you something you gotta water, feed or walk, it’s time to dump her’. Ray’s attitude towards the plant expresses his resentment of commitment and responsibility, and to some extent the plant becomes a metaphor for his relationship with Tim. When Tim first arrives in Ray’s apartment, after having been dropped off by Kitty, Tim sees the plant and tells Ray, ‘You should water this: it’s dying’. Shortly after, Tim hatches his own plan to blackmail Ray into ‘watering’ his relationship with his estranged son.  Along with Ray’s extended stays in prison, the death of Tim’s mother is a key reason for the breakdown of Tim’s relationship with Ray: at the start of the film, Tim has spent three years with Kitty following the death of his mother to cancer. During his first meeting with Ray, Tim tells his father, ‘Brought you something, dad: a picture of mom and me’, presenting Ray with a photograph of Tim next to his mother’s headstone. Initially, in his conversations with Tim, Ray uses humour as a shield: when Tim observes that Ray learnt to make and decorate cakes in prison, Ray responds by joking, ‘Yeah, it was kind of a course I took. I wanted to get into counterfeiting class, but it was all full up’. However, this façade soon cracks, and there’s a growing sense of sadness and guilt in relation to Ray’s attitude towards his son: when Tim asks Ray if he got the letters he wrote to him in prison and questions why Ray didn’t write back, Ray asserts, ‘I guess I didn’t know what to say, Tim. I mean, what’d I put: “Having a wonderful time; wish you were here”?’ Along with Ray’s extended stays in prison, the death of Tim’s mother is a key reason for the breakdown of Tim’s relationship with Ray: at the start of the film, Tim has spent three years with Kitty following the death of his mother to cancer. During his first meeting with Ray, Tim tells his father, ‘Brought you something, dad: a picture of mom and me’, presenting Ray with a photograph of Tim next to his mother’s headstone. Initially, in his conversations with Tim, Ray uses humour as a shield: when Tim observes that Ray learnt to make and decorate cakes in prison, Ray responds by joking, ‘Yeah, it was kind of a course I took. I wanted to get into counterfeiting class, but it was all full up’. However, this façade soon cracks, and there’s a growing sense of sadness and guilt in relation to Ray’s attitude towards his son: when Tim asks Ray if he got the letters he wrote to him in prison and questions why Ray didn’t write back, Ray asserts, ‘I guess I didn’t know what to say, Tim. I mean, what’d I put: “Having a wonderful time; wish you were here”?’

Though the film offers an ultimately sentimental view of Tim and Ray’s relationship, the script seems to attempt to deflect accusations of sentimentality through referencing The Oprah Winfrey Show (1986-2011) as an index of an overly self-reflective approach to the world and our relationships with one another. In one sequence, Tim and Ray go fishing together. Tim struggles to cast his line. ‘Didn’t anyone ever teach you how to cast before?’, Ray asks him. ‘No, my father was usually in jail’, Tim says. Ray shows Tim how to cast. ‘Did you father teach you that?’, Tim asks. ‘No, Tim, he didn’t’, Ray tells his son. ‘Guess your family was dysfunctional too’, Tim says, ‘That’s what you and me are, we’re dysfunctional’. ‘You’ve been watching way too much Oprah’, Ray tells him in response. For Ray, the robbery represents what he believes is his last chance at going straight. He reasons that the coins that belonged to the elderly lady who passed away have now been seized by the US government ‘to buy limousines for fat cat politicians’. He aims to use his share to buy the bakery. ‘So what you’re saying is, you wanna go straight; but in order to do that, you steal?’, Tim asks. ‘Yeah’, Ray says. ‘I’m eleven, and that seems dumb even to me’, Tim asserts.  Danson’s natural onscreen warmth somewhat works against his character: there’s never really a suggestion that he and Tim will fail to bond, or that he will allow Tim to be imperiled by the threats of Bobby. For his part, Bobby alludes to another, more simple, brand of parental authority: when Tim reveals that he has hidden the coins that the gang have stolen, Bobby declares, ‘If that was my old man, he would take his belt to me, which is exactly what I’m gonna do’. He is, of course, restrained by both Ray and Carl. Bobby’s intention to harm Tim seems as unsettling today as Joe Pesci’s character’s desire to harm Kevin McAllister in Home Alone or the actions of the three crooks – played by Joe Mantegna, Joe Pantoliano and Brian Haley – who imperil the baby in Patrick Read Johnson’s Baby’s Day Out (1994, also scripted by John Hughes). Following Tim into the lavatory in a science museum, intending to beat Tim until he reveals the location of the coins, Bobby finds himself outwitted by Tim and bursts into the wrong stall where a small boy protests, ‘Daddy, he’s watching me pee!’ Jokes such as this, which proliferate throughout Culkin’s films of this era, are presented for slapstick value rather than as moments of black humour and offer uneasy moments of laughter for the audience that is mitigated by the genuine warmth of the father-son relationship that sits at the heart of the picture. Danson’s natural onscreen warmth somewhat works against his character: there’s never really a suggestion that he and Tim will fail to bond, or that he will allow Tim to be imperiled by the threats of Bobby. For his part, Bobby alludes to another, more simple, brand of parental authority: when Tim reveals that he has hidden the coins that the gang have stolen, Bobby declares, ‘If that was my old man, he would take his belt to me, which is exactly what I’m gonna do’. He is, of course, restrained by both Ray and Carl. Bobby’s intention to harm Tim seems as unsettling today as Joe Pesci’s character’s desire to harm Kevin McAllister in Home Alone or the actions of the three crooks – played by Joe Mantegna, Joe Pantoliano and Brian Haley – who imperil the baby in Patrick Read Johnson’s Baby’s Day Out (1994, also scripted by John Hughes). Following Tim into the lavatory in a science museum, intending to beat Tim until he reveals the location of the coins, Bobby finds himself outwitted by Tim and bursts into the wrong stall where a small boy protests, ‘Daddy, he’s watching me pee!’ Jokes such as this, which proliferate throughout Culkin’s films of this era, are presented for slapstick value rather than as moments of black humour and offer uneasy moments of laughter for the audience that is mitigated by the genuine warmth of the father-son relationship that sits at the heart of the picture.

The film is uncut and runs for 108:47 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a single-layer Blu-ray disc, Getting Even with Dad is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and is in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on a single-layer Blu-ray disc, Getting Even with Dad is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and is in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

There’s a slight softness to the image here and there, and a slightly muted grain structure, that suggests some digital noise reduction has been applied somewhere along the line. The source is most likely an older off-the-shelf master. Nevertheless, the HD presentation on this Blu-ray has a sense of depth and detail to the image, combined with strong and nicely-balanced contrast levels, that elevates it well above the film’s previous DVD incarnations. The presentation is certainly a big improvement over the film’s DVD releases and is a pleasing experience overall. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo track. This is clear and clean with good range; it’s an unfussy track, but there’s some separation when it’s needed (eg, in the theme park sequence) and dialogue is audible throughout. Sadly there are no subtitles, however.

Extras

The disc includes the film’s trailer (2:30).

Overall

In many ways, Getting Even with Dad feels like a leaden retreading of the Home Alone formula, with Culkin playing a technology savvy, scheming youngster who gets the better of his elders in a number of scenarios that are rife with slapstick potential. However, there’s a warmth to the film that largely emanates from Danson’s performance as the estranged father, and revisiting this film (which I initially saw as a teenager) from a newer position as a father myself, the film could be said to have acquired a greater significance – articulating the feelings that seem to go along with parenthood, that one day your child will find you utterly redundant. (This is the same thematic territory that enriches family films such as Toy Story 2, 1999, for example.) The film as a whole has the feeling of a script that was rewritten to capitalise on the screen persona Culkin cultivated in the Home Alone films, accommodating (or some might say, crowbarring into the scenario) some of the aspects of the Kevin McAllister character that audiences responded to so well in the first and second pictures in that franchise. That said, Getting Even with Dad is not without its own merits, and for the most part (except for Bobby’s outbursts of cruelty towards Tim, which represent an undercurrent of violence that bubbles beneath the slapstick humour) the picture is an entertaining, often amusing film. At the time, it felt very much of its era, and revisiting the film today this seems even more true – owing to its web of connections with Culkin’s other films of the era and the casting of Danson as a lothario who avoids responsibility and commitment. In many ways, Getting Even with Dad feels like a leaden retreading of the Home Alone formula, with Culkin playing a technology savvy, scheming youngster who gets the better of his elders in a number of scenarios that are rife with slapstick potential. However, there’s a warmth to the film that largely emanates from Danson’s performance as the estranged father, and revisiting this film (which I initially saw as a teenager) from a newer position as a father myself, the film could be said to have acquired a greater significance – articulating the feelings that seem to go along with parenthood, that one day your child will find you utterly redundant. (This is the same thematic territory that enriches family films such as Toy Story 2, 1999, for example.) The film as a whole has the feeling of a script that was rewritten to capitalise on the screen persona Culkin cultivated in the Home Alone films, accommodating (or some might say, crowbarring into the scenario) some of the aspects of the Kevin McAllister character that audiences responded to so well in the first and second pictures in that franchise. That said, Getting Even with Dad is not without its own merits, and for the most part (except for Bobby’s outbursts of cruelty towards Tim, which represent an undercurrent of violence that bubbles beneath the slapstick humour) the picture is an entertaining, often amusing film. At the time, it felt very much of its era, and revisiting the film today this seems even more true – owing to its web of connections with Culkin’s other films of the era and the casting of Danson as a lothario who avoids responsibility and commitment.

The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is pleasing overall, though it’s light on contextual material. References: Dubner, Stephen J, 1993: ‘My Art Belongs to Daddy’. New York Magazine (29 November, 1993): 52-7

|

|||||

|