|

|

Videodrome AKA Zonekiller (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th August 2015). |

|

The Film

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1982) Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1982)

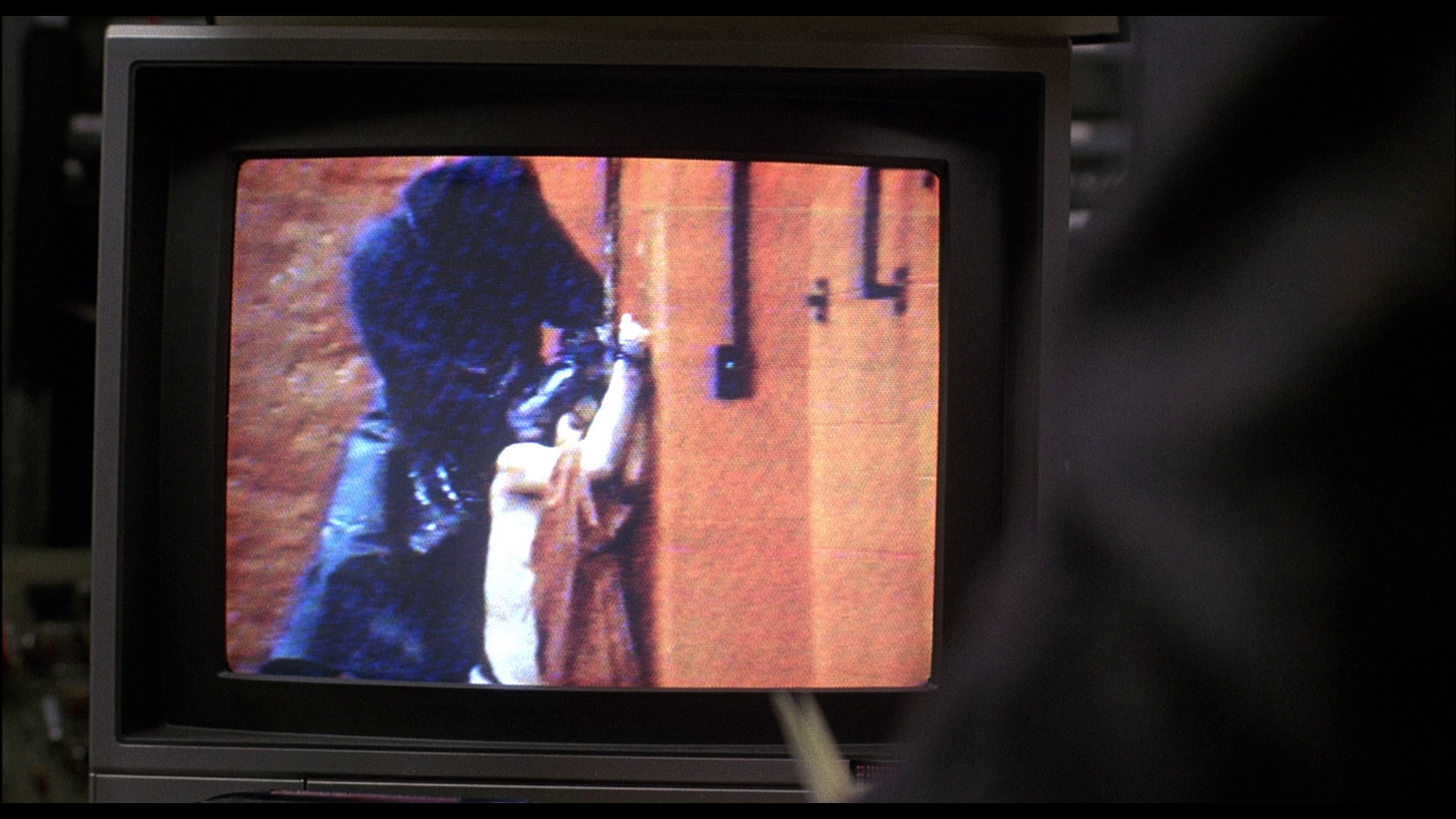

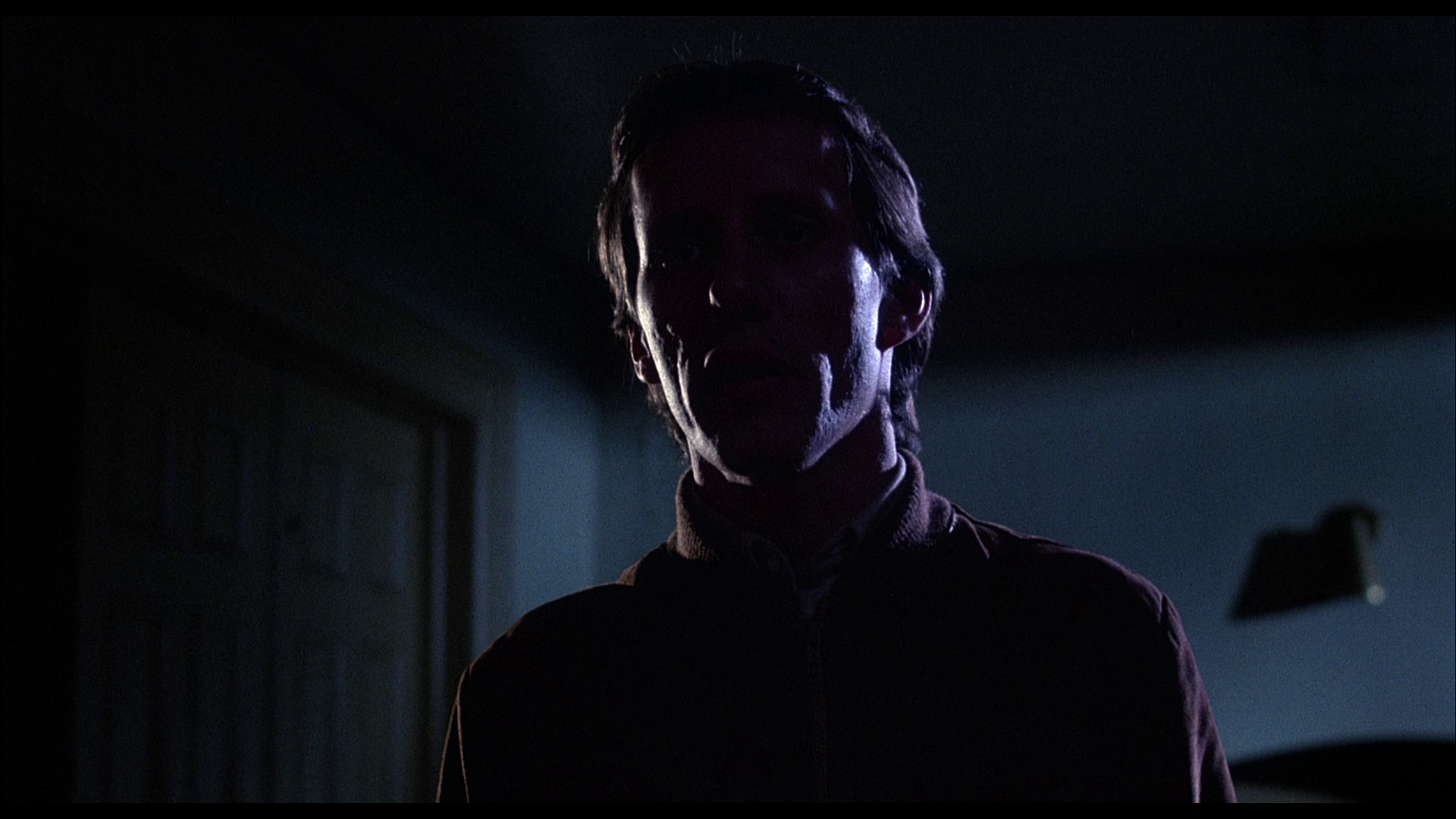

In his book about David Cronenberg, Ernest Mathijs suggests that during the 1980s, an era in which horror ‘franchises’ (for example, the Friday the 13th films) became de rigueur, many of the horror auteurs – such as George A Romero, Tobe Hooper and Larry Cohen – whose work made a splash in the 1970s struggled to maintain the quality of their output (Mathijs, 2008: 103). However, David Cronenberg’s work in that decade went from strength to strength, allying Cronenberg with John Carpenter and Wes Craven – both of whom delivered some of their best films in the 1980s – though the bulk of Carpenter and Craven’s output was ‘virtually ignored in favour of their programmatic involvements in the Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street franchises’ (ibid.). Videodrome (1983), Mathijs argues, may be considered the ultimate Cronenberg film. It is a picture which contains all of the major motifs within Cronenberg’s films: ‘science, technology (both shiny and fleshy), body horror, gore, isolation, hallucination, medicine, paranoia, family dysfunctions, physical sexuality, male and female sado-masochism’ (ibid.). The film opens with Max Renn (James Woods), president of Civic TV (Channel 83), receiving a video-recording of a wake-up call from one of the station’s employees, Bridey James (Julie Khaner). Max has a meeting with the representatives of Hiroshima Video, who want to sell Max their new thirteen-part erotic series set in feudal Japan, Samurai Dreams. However, Max seems unimpressed with this offering, finding it too ‘soft’: Max is ‘looking for something that’ll break through, you know. Something tough’.  ‘Something tough’ is presented to Max by the station’s technician Harlan (Peter Dvorsky). Harlan is the operator of the pirate satellite dish owned by the station; it’s a clandestine operation that involves Harlan unscrambling foreign broadcasts. Harlan shows Max a new signal, the Videodrome signal. The technology behind the Videodrome signal is impressive, Harlan tells Max, with the broadcasters going to great lengths to protect the signal from eavesdroppers like Harland (‘They’ve got an unscrambler scrambler, if you know what I mean’). The signal’s country of origin, Harlan says, appears to be Malaysia. The footage Harlan has managed to unscramble depicts a woman restrained by two men in overalls, in what appears to be a high-tech torture chamber. The woman is held against an electrified clay wall before being throttled by the men. ‘Grotesque, as promised’, Harlan says. Max is unfazed. ‘Something tough’ is presented to Max by the station’s technician Harlan (Peter Dvorsky). Harlan is the operator of the pirate satellite dish owned by the station; it’s a clandestine operation that involves Harlan unscrambling foreign broadcasts. Harlan shows Max a new signal, the Videodrome signal. The technology behind the Videodrome signal is impressive, Harlan tells Max, with the broadcasters going to great lengths to protect the signal from eavesdroppers like Harland (‘They’ve got an unscrambler scrambler, if you know what I mean’). The signal’s country of origin, Harlan says, appears to be Malaysia. The footage Harlan has managed to unscramble depicts a woman restrained by two men in overalls, in what appears to be a high-tech torture chamber. The woman is held against an electrified clay wall before being throttled by the men. ‘Grotesque, as promised’, Harlan says. Max is unfazed.

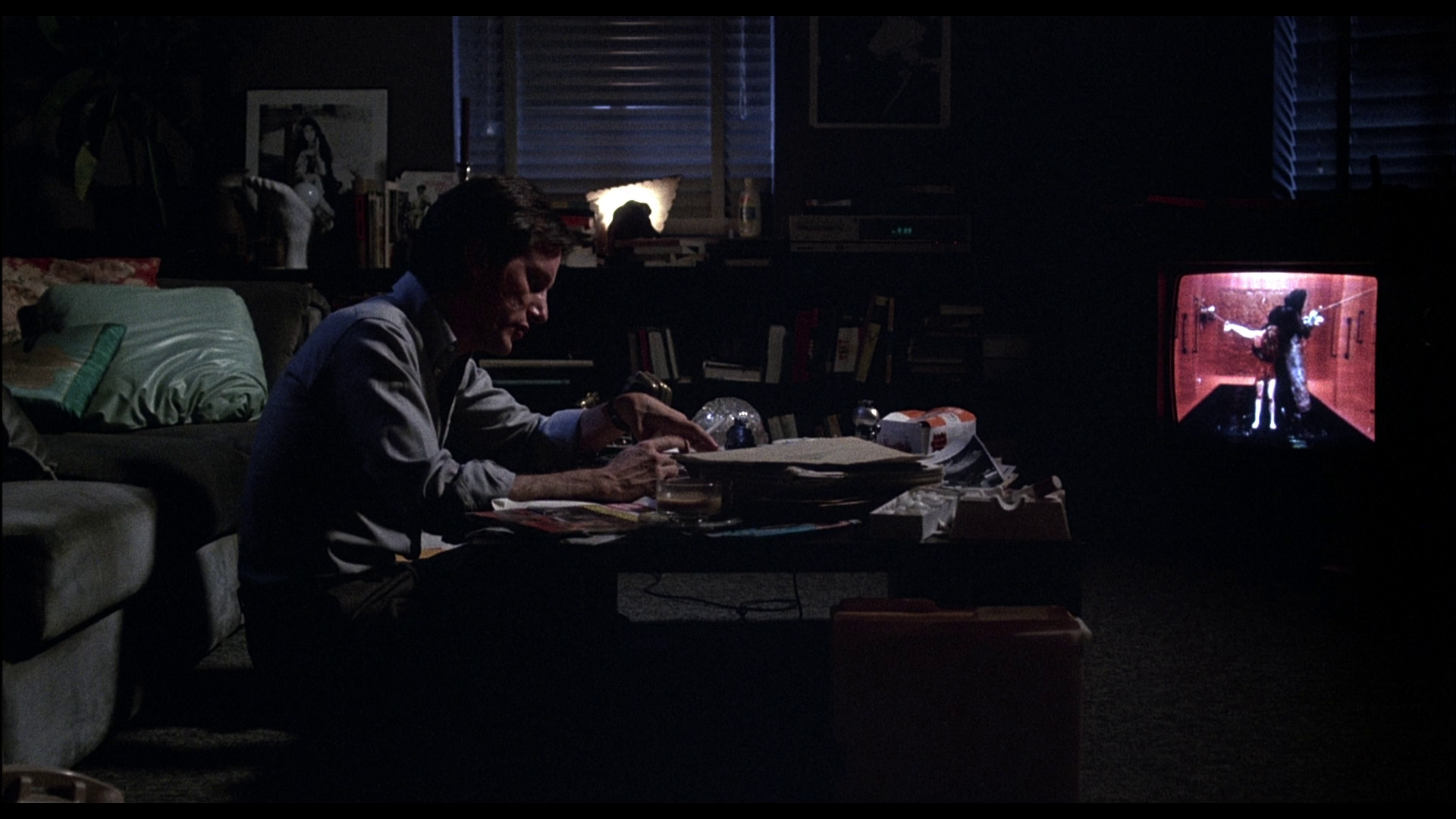

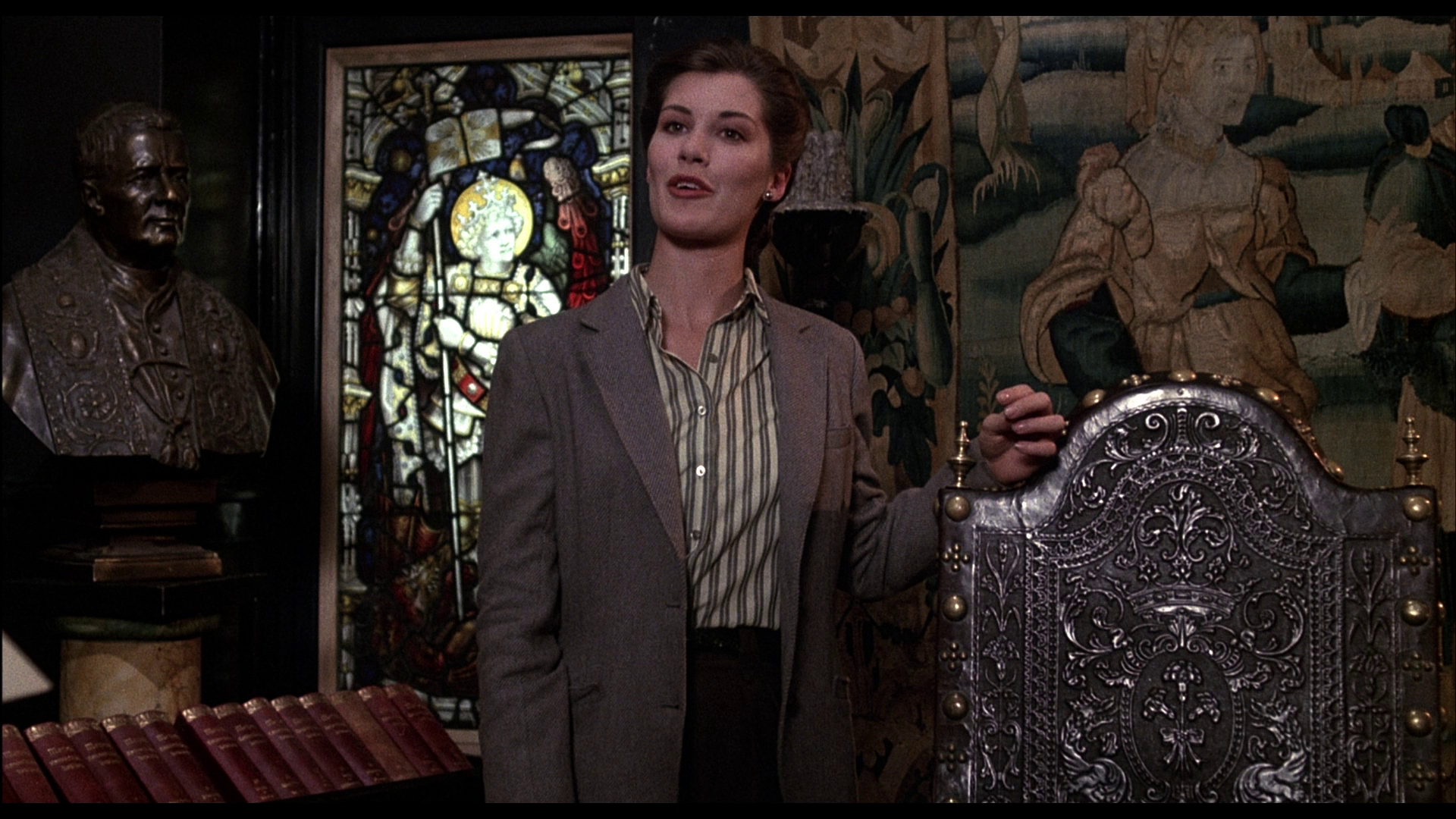

During a televised interview on The Rena King Show, Max meets local radio show host Nikki Brand (Deborah Harry) and ‘media prophet’ Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley) – the latter of whom will only ‘appear on television on television’, leading the host of the show (Lally Cadeau) to interview O’Blivion via a television monitor on the studio floor. Max interrupts the show to flirt with Nikki and ask her out to dinner. Max and Nikki begin a sexual relationship: Nikki reveals herself to be a masochist, asking a shocked Max to ‘Take out your Swiss army knife and cut me here [on her shoulder], just a little’. Nikki displays a strong interest in the Betamax recordings of the Videodrome broadcasts that are in the possession of Max. ‘I wonder how you get to be a contestant on this show?’, Nikki asks. ‘I don’t know. Nobody seems to come back next week’, Max tells her. Harlan reveals to Max that the Videodrome signal isn’t sourced from Malaysia but rather from Pittsburgh. Despite Max’s warnings, Nikki visits Pittsburgh on an assignment for her radio station and promises to track down the producers of Videodrome. Meanwhile, Max begins to experience disturbing hallucinations which seem to have some relationship to his exposure to the Videodrome broadcast. Acting on the advice of Masha (Lynne Gorman), one of the distributors with whom he negotiates, Max attempts to make contact with Brian O’Blivion at O’Blivion’s Cathode Ray Mission – a soup kitchen-type place in which the homeless can have free access to television. There, Max makes contact with Brian O’Blivion’s daughter Bianca O’Blivion (Sonja Smits). Bianca tells Max that ‘My father has not engaged in conversation for over twenty years. The monologue is his preferred mode of discourse’ and gives Max a videotaped message from her father.  Via the videotaped recording, O’Blivion reveals to Max that his ‘reality is already half video hallucination. If you’re not careful it will become total hallucination. You’ll have to learn to live in a very strange new world’. Max experiences yet another hallucination whilst watching the tape: Nikki appears on screen and throttles O’Blivion, and the television cabinet begins to sigh and swell as Nikki tells Max, ‘Come to me. Come to Nikki’. Max buries his head in the now deeply swollen television screen, which bears a close-up of Nikki’s red lips. Then he wakes up the next morning. Via the videotaped recording, O’Blivion reveals to Max that his ‘reality is already half video hallucination. If you’re not careful it will become total hallucination. You’ll have to learn to live in a very strange new world’. Max experiences yet another hallucination whilst watching the tape: Nikki appears on screen and throttles O’Blivion, and the television cabinet begins to sigh and swell as Nikki tells Max, ‘Come to me. Come to Nikki’. Max buries his head in the now deeply swollen television screen, which bears a close-up of Nikki’s red lips. Then he wakes up the next morning.

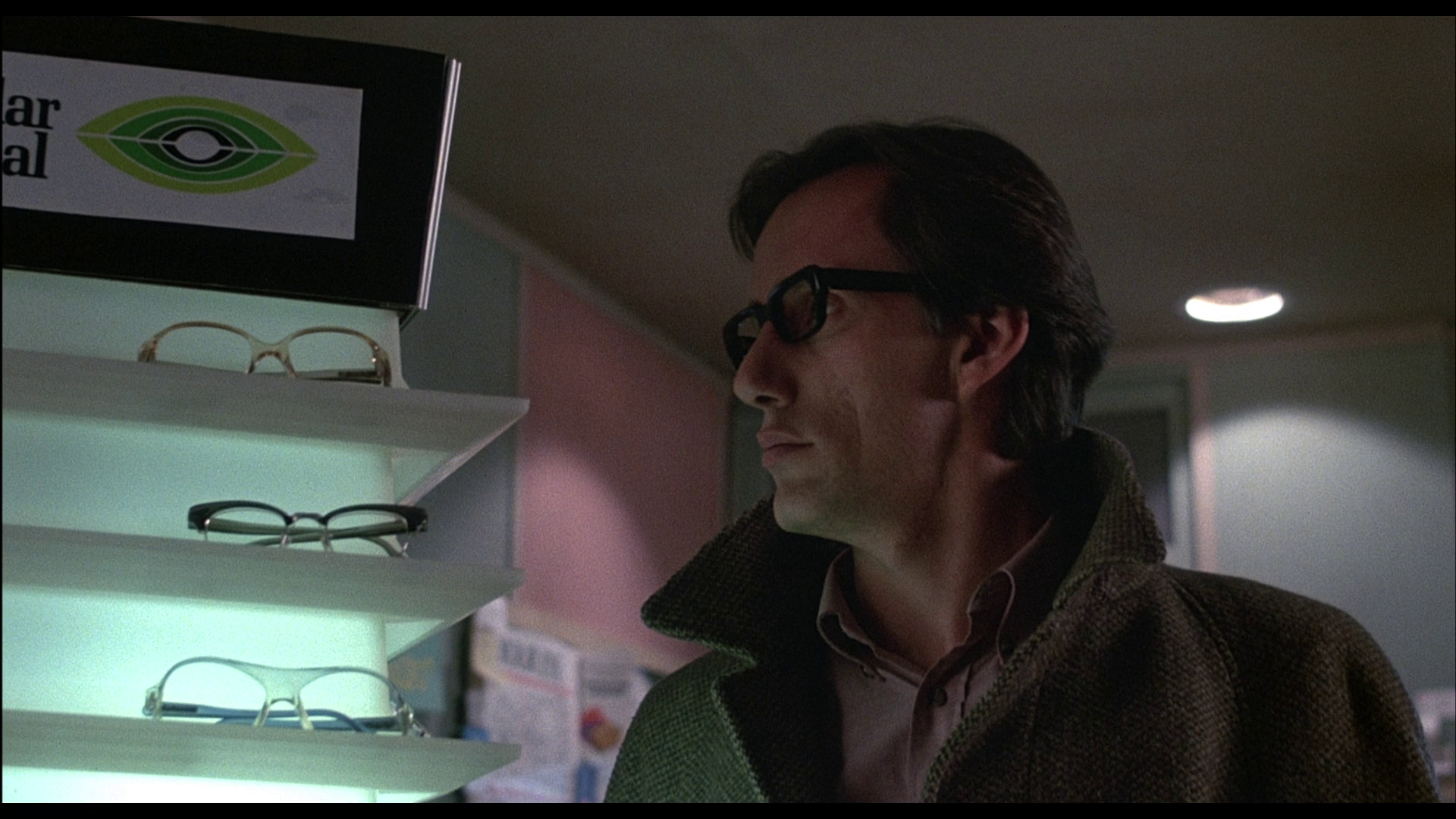

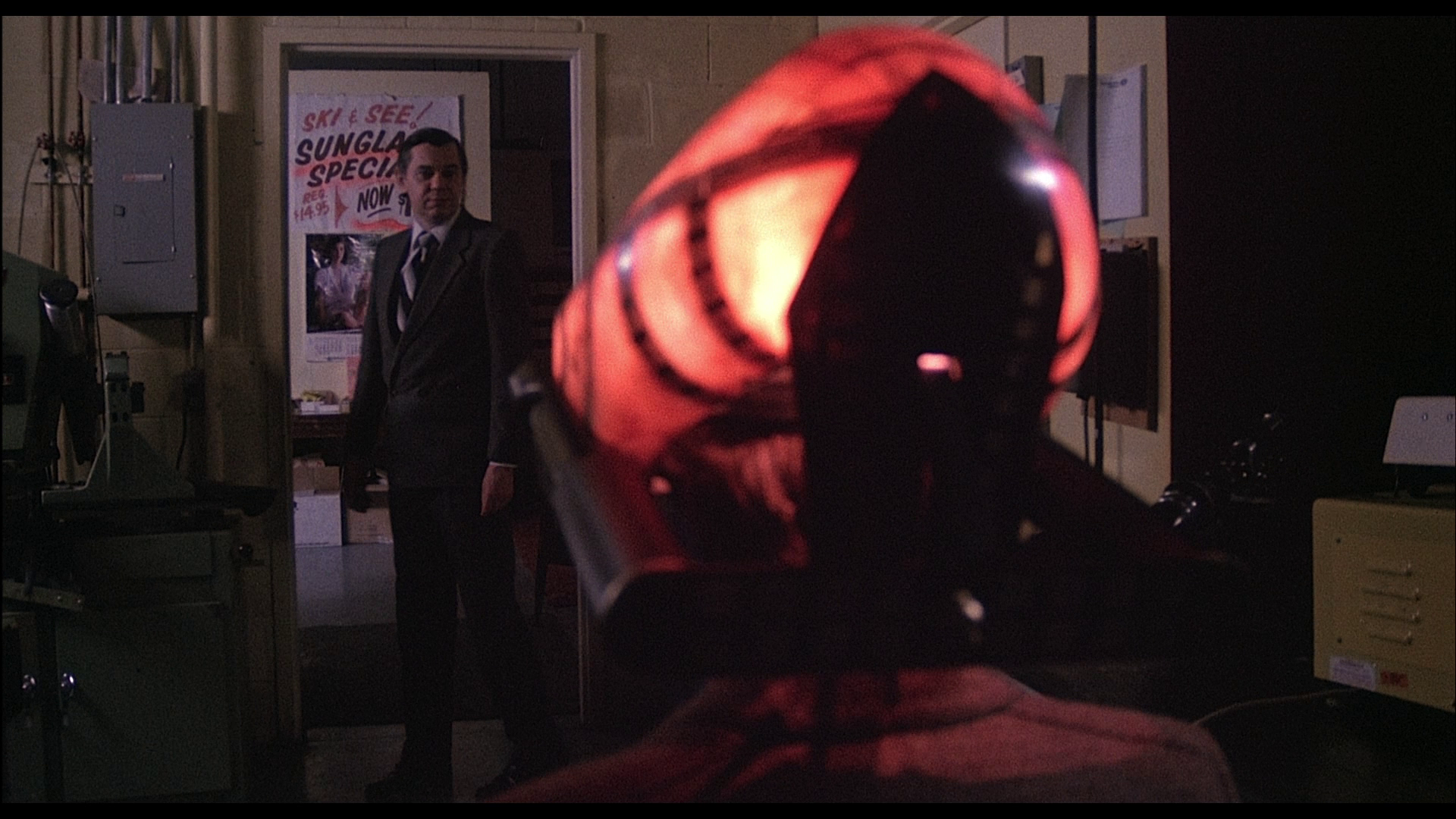

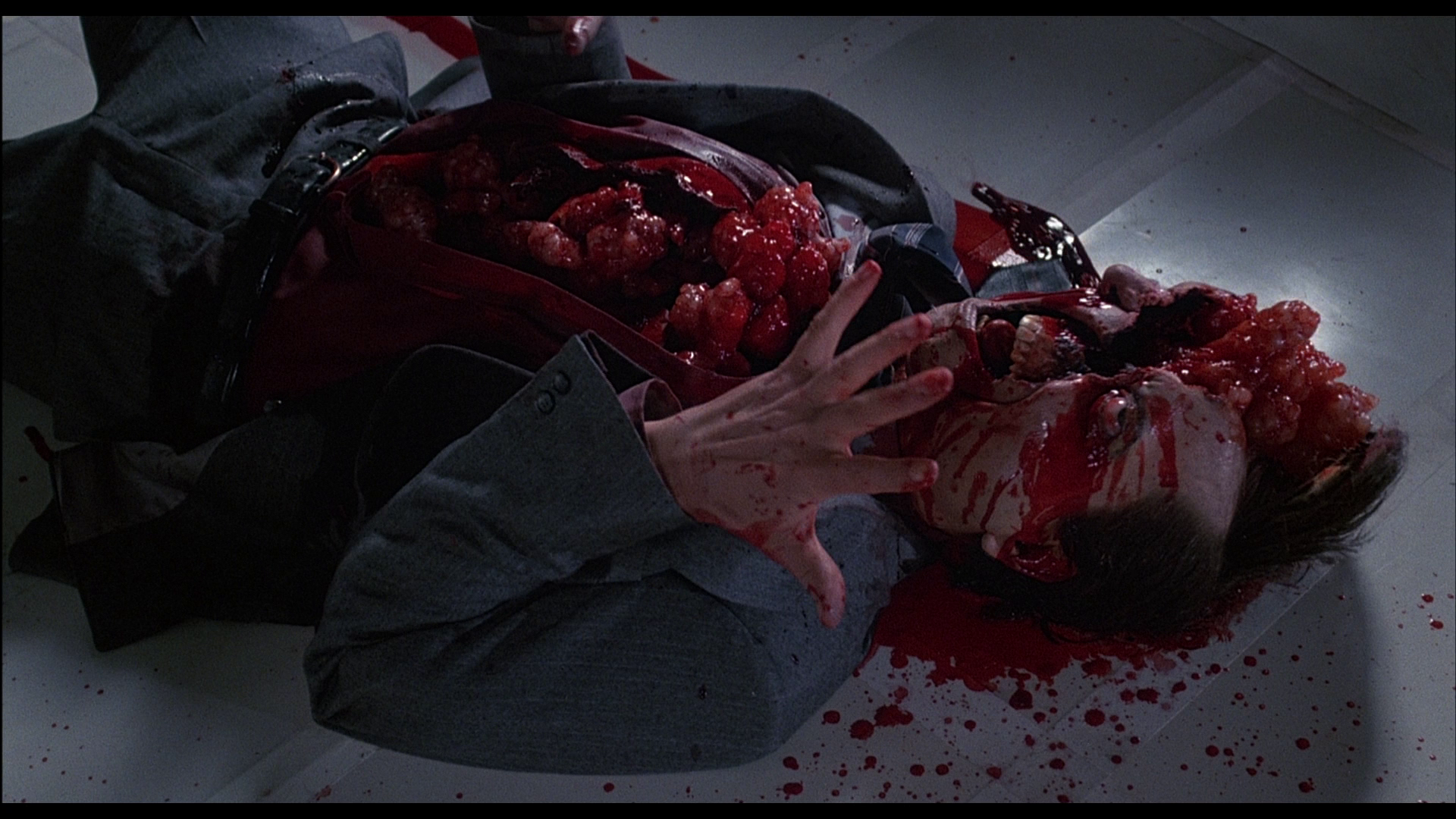

Disturbed by his experience, Max pays a visit to Bianca. Bianca tells Max that her father has been dead for almost a year, and has left behind a store of videotaped monologues which she uses to perpetuate the illusion that Brian O’Blivion is still alive. Brian O’Blivion, Bianca says, helped to develop the Videodrome signal in conjunction with Spectacular Optical, a chain of opticians and eyeglass manufacturers and retailers who also have a contract with the US government for the production of missile guidance systems. When O’Blivion realised that his work would be used for what seems to be a military purpose, he ‘tried to take it away from them, and so they killed him quetly’. A sideproduct of O’Blivion’s work on the Videodrome signal was the growth of a tumour in his brain and accompanying hallucinations: O’Blivion believed that the tumour was caused by the hallucinations rather than the other way around. The Videodrome signal itself is not tied to the ‘snuff’ television broadcast that Max was shown by Harlan: Bianca tells Max that ‘the Videodrome signal, the one that does the damage [ie, causes the hallucinations and tumours], can be delivered under a test signal, anything’. The hallucinations it causes, Bianca asserts, are determined by the tone of the broadcast that the signal is inserted into.  Max is called to a meeting with Barry Convex, the owner of Spectacular Optical. Convex reveals to Max that Harlan, who Convex ‘planted’ within Channel 83, has been exposing Max to ‘test transmissions’ of the Videodrome signal: Convex and his group plan to program Max to assassinate the other owners of Channel 83, thus allowing Spectacular Optical to seize control of the station and begin broadcasting the Videodrome signal from it, because, as Harlan says, ‘America is getting soft, patron, and the rest of the world is getting tough. Very, very tough. We’re entering savage new times, and we’re going to have to be pure, and erect, and strong, if we’re going to survive them’. Max is called to a meeting with Barry Convex, the owner of Spectacular Optical. Convex reveals to Max that Harlan, who Convex ‘planted’ within Channel 83, has been exposing Max to ‘test transmissions’ of the Videodrome signal: Convex and his group plan to program Max to assassinate the other owners of Channel 83, thus allowing Spectacular Optical to seize control of the station and begin broadcasting the Videodrome signal from it, because, as Harlan says, ‘America is getting soft, patron, and the rest of the world is getting tough. Very, very tough. We’re entering savage new times, and we’re going to have to be pure, and erect, and strong, if we’re going to survive them’.

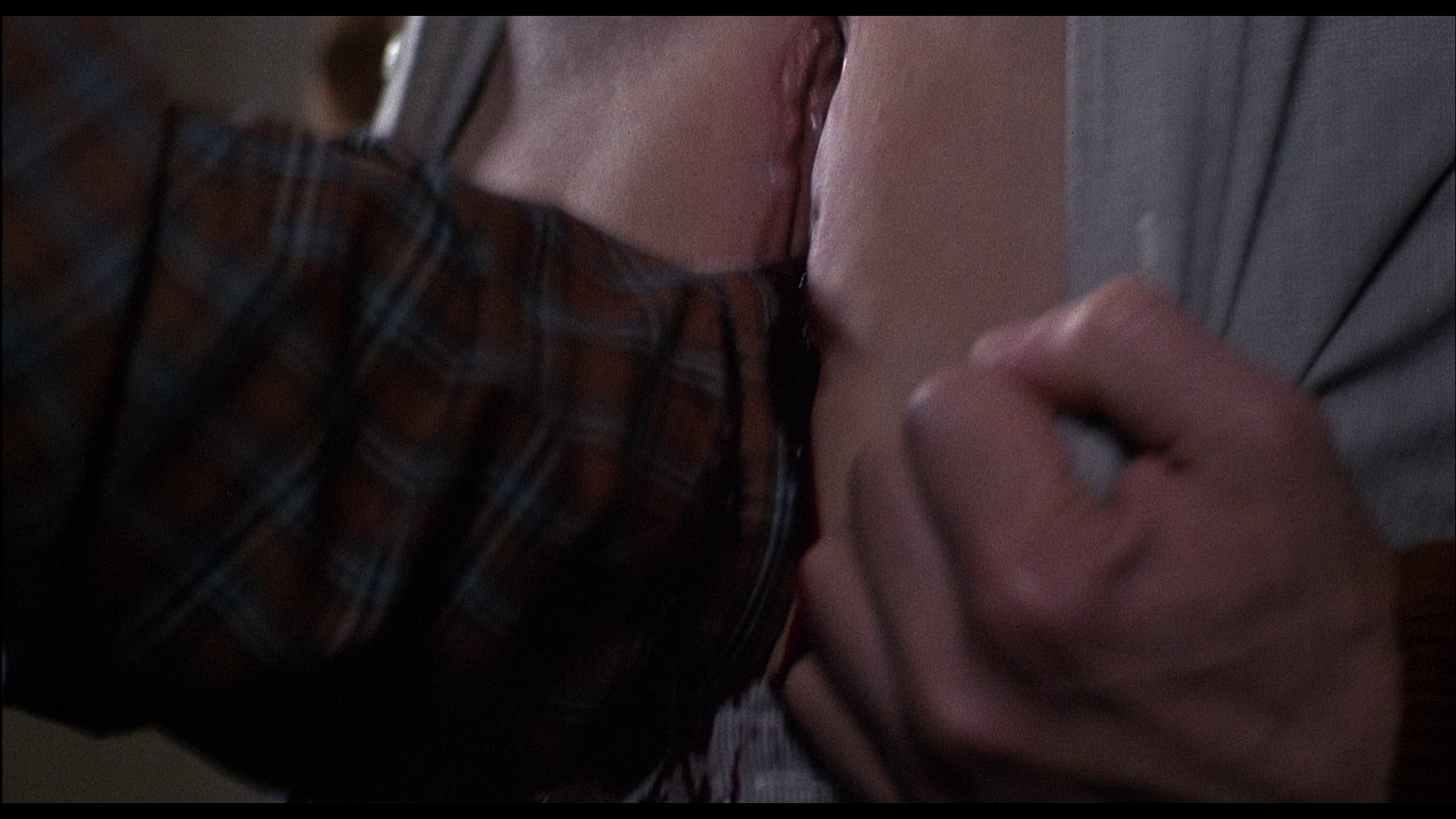

Rumour has it that David Cronenberg was inspired to make Videodrome after seeing the remarkably authentic-looking snuff movie sequences from Aristide Massaccesi’s notorious Emanuelle in America (1977) at an exhibition organised by the Ontario Censor Board to validate their work. Whether this is true or not is open to debate, but certainly Videodrome initially connects its depiction of filmed torture and murder to the same myths perpetrated in Massaccesi’s film: chiefly, that such material originates in exotic locales like Asia or South America (‘where life is cheap’, as the tagline on the posters for the Findlay’s Snuff declared in 1976). However, as Videodrome’s narrative progresses these myths are exploded: Harlan initially declares that the Videodrome signal is originating within Malaysia but later reveals that it appears to be coming from much closer to home, in Pittsburgh; and later on, it is revealed that the Videodrome footage is in fact not part of an underground broadcast at all but is instead on videotape, put together by Spectacular Optical, presumably as part of their military contract with the government, and used as a brainwashing tool (the footage is shown by Harlan, a ‘plant’ within Channel 83, to Max in order to ‘create’ an assassin out of him). So this profoundly subversive film begins with the usual association of ‘snuff movies’ with exotic locations before revealing that the source of this footage is within the US, and has in fact been put together by a company (Spectacular Optical) which has a contract with the United States Department of Defense.  There’s the hint of a conspiracy but its precise aims are never clarified: the audience is as much in the dark about its precise nature as Max Renn himself. The plan seems to be to seize Channel 83 and use it to broadcast the Videodrome signal as a means of preparing America for a new era of violence. The use of the Videodrome signal on Max, as a means of turning him into an assassin who can be programmed by his handlers, is facilitated by the violence and sadistic sexuality within the Videodrome broadcast. As Convex tells Max, ‘exposure to violence opens up the receptors in the brain and the spine, and that allows the signal to seep in’. Convex ‘programs’ Max into assassinating the other owners of Channel 83 by inserting a Betamax tape into the vaginal slit that appears in Max’s stomach: a very visual metaphor for the impact of the media on its audience. Speaking with Max after he has been programmed in such a way by Convex, Bianca tells Max that ‘You’re an assassin now, for Videodrome. They can program you. They can play you like a videotape recorder. They can make you do what they want’. There’s the hint of a conspiracy but its precise aims are never clarified: the audience is as much in the dark about its precise nature as Max Renn himself. The plan seems to be to seize Channel 83 and use it to broadcast the Videodrome signal as a means of preparing America for a new era of violence. The use of the Videodrome signal on Max, as a means of turning him into an assassin who can be programmed by his handlers, is facilitated by the violence and sadistic sexuality within the Videodrome broadcast. As Convex tells Max, ‘exposure to violence opens up the receptors in the brain and the spine, and that allows the signal to seep in’. Convex ‘programs’ Max into assassinating the other owners of Channel 83 by inserting a Betamax tape into the vaginal slit that appears in Max’s stomach: a very visual metaphor for the impact of the media on its audience. Speaking with Max after he has been programmed in such a way by Convex, Bianca tells Max that ‘You’re an assassin now, for Videodrome. They can program you. They can play you like a videotape recorder. They can make you do what they want’.

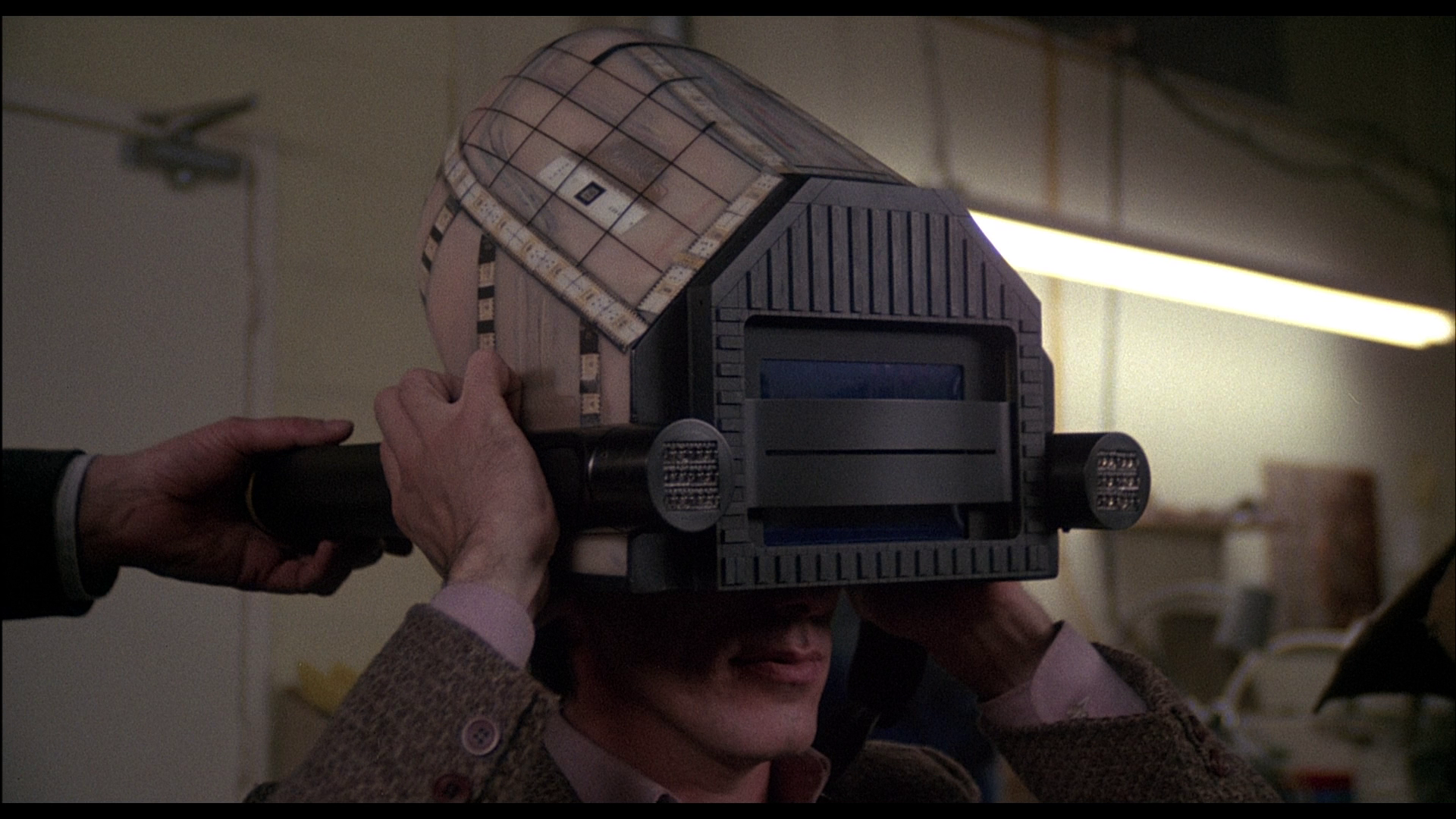

The use of experimental science to create an assassin, and the second half of the film’s focus on conspiracy theories, seems to allude to the legends surrounding the CIA’s mind control experiment Project MKULtra, which reputedly involved the use of mind-altering drugs – including hallucinogens – in order to modify the behaviour of the test subjects or exact ‘mind control’ (as a means of what’s often popularly termed ‘brainwashing’). In particular, Videodrome draws on the popular conspiracy theory which suggests that commercial cinema and television (and other forms of entertainment) are an extension of the Project MKUltra program and demonstrate an attempt to use the media to manipulate the behaviour of citizens on a large scale.  Cultural critic Scott Bukatman has referred to Videodrome as ‘the most estranging portrayal of image addiction and viral invasion since [William S] Burroughs’ (Bukatman, 2007: 232). The world within Videodrome is saturated with media messages: Max Renn’s alarm clock is a wake-up call, recorded on videocassette and presented to him the night before, by one of Channel 83’s employees, Bridey James (‘Max, it’s that time again’, her breathy voice declares via one of these tapes at the start of the film, ‘Time to slowly, painfully ease yourself back into consciousness’); Civic TV’s slogan is ‘The one you take to bed with you’, suggestive of how dominant television is within the culture depicted within the film; Brian O’Blivion has established a Cathode Ray Mission, managed by his daughter Bianca, in which the homeless are allowed access to television in the belief that, in the words of Bianca O’Blivion, ‘Watching TV will help patch them back into the world’s mixing bowl’. This seems frighteningly prescient in the digital age, given the current attempts to tackle ‘digital exclusion’ by establishing ‘UK Online Centres’ where participants can access the Internet for free. The rhetoric surrounding this often echoes Brian O’Blivion’s gnomic prophecies: for example, the declaration on Economic and Social Research Council’s Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK site that ‘[t]here’s a story that we tell ourselves about poverty and digital exclusion: the poorest people are digitally excluded; digital exclusion perpetuates poverty: therefore, getting people online will help lift them out of poverty’ (Burton, 2013: np). Alongside this, when Max visits Spectacular Optical to converse with Convex, Convex places a curious headset on Max which, Convex explains, is a prototype that will record Max’s hallucinations. With a view inside that resembles that of Fisher Price’s Pixelvision camera (developed a few years later, in 1987), the headset seems to anticipate the fad for Virtual Reality headsets in the 1990s (which has been reawakened more recently by the interest in the Oculus Rift technology and Google Glass). Cultural critic Scott Bukatman has referred to Videodrome as ‘the most estranging portrayal of image addiction and viral invasion since [William S] Burroughs’ (Bukatman, 2007: 232). The world within Videodrome is saturated with media messages: Max Renn’s alarm clock is a wake-up call, recorded on videocassette and presented to him the night before, by one of Channel 83’s employees, Bridey James (‘Max, it’s that time again’, her breathy voice declares via one of these tapes at the start of the film, ‘Time to slowly, painfully ease yourself back into consciousness’); Civic TV’s slogan is ‘The one you take to bed with you’, suggestive of how dominant television is within the culture depicted within the film; Brian O’Blivion has established a Cathode Ray Mission, managed by his daughter Bianca, in which the homeless are allowed access to television in the belief that, in the words of Bianca O’Blivion, ‘Watching TV will help patch them back into the world’s mixing bowl’. This seems frighteningly prescient in the digital age, given the current attempts to tackle ‘digital exclusion’ by establishing ‘UK Online Centres’ where participants can access the Internet for free. The rhetoric surrounding this often echoes Brian O’Blivion’s gnomic prophecies: for example, the declaration on Economic and Social Research Council’s Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK site that ‘[t]here’s a story that we tell ourselves about poverty and digital exclusion: the poorest people are digitally excluded; digital exclusion perpetuates poverty: therefore, getting people online will help lift them out of poverty’ (Burton, 2013: np). Alongside this, when Max visits Spectacular Optical to converse with Convex, Convex places a curious headset on Max which, Convex explains, is a prototype that will record Max’s hallucinations. With a view inside that resembles that of Fisher Price’s Pixelvision camera (developed a few years later, in 1987), the headset seems to anticipate the fad for Virtual Reality headsets in the 1990s (which has been reawakened more recently by the interest in the Oculus Rift technology and Google Glass).

Videodrome was made in an era in which home video was still a fairly new medium (the special features tell us that Betamax tapes were used in the film, over VHS cassettes, owing to their size and the practicalities of the effects in the sequence in which Convex inserts a videotape into Renn’s stomach). The technology within the film may seem slightly antiquated though the ideas are arguably more relevant than ever: some of Brian O’Blivion’s statements (for example, his declaration that we will all live by assumed ‘screen’ names) seem incredibly prophetic in the age of social media; and Harlan’s (apparent) discovery of the encrypted Videodrome transmission still has all sorts of resonance in an era in which urban legends proliferate about ‘red rooms’ on the Internet in which torture and murder are enacted for paying spectators who get their kicks from such footage. Videodrome was made in an era in which home video was still a fairly new medium (the special features tell us that Betamax tapes were used in the film, over VHS cassettes, owing to their size and the practicalities of the effects in the sequence in which Convex inserts a videotape into Renn’s stomach). The technology within the film may seem slightly antiquated though the ideas are arguably more relevant than ever: some of Brian O’Blivion’s statements (for example, his declaration that we will all live by assumed ‘screen’ names) seem incredibly prophetic in the age of social media; and Harlan’s (apparent) discovery of the encrypted Videodrome transmission still has all sorts of resonance in an era in which urban legends proliferate about ‘red rooms’ on the Internet in which torture and murder are enacted for paying spectators who get their kicks from such footage.

From the outset, Max is depicted as a man who is desperate to push the proverbial envelope in search of a larger audience for Channel 83 – and also, it is suggested, owing to his own fascination with violence and sexual sadism. (When Max tells Convex that he only watched the Videodrome broadcast for ‘business reasons’, Convex suggests that Max got his ‘kicks watching torture and murder’.) After watching the final episode of Samurai Dreams, in which a wooden dildo disguised as a geisha doll is used graphically onscreen, Max asks his colleagues at Channel 83, ‘What do you think? Can we get away with it? Do we wanna get away with it?’ Max ultimately dismisses Samurai Dreams as ‘soft. Something… soft about it’. Likewise, when Masha (Lynne Gorman) offers Max her new show, Apollo and Dionysus, an erotic programme set in the time of Ancient Greece, Max dismisses it and tells Masha ‘I’m looking for something a bit more… contemporary’. He tells Masha of his interest in Videodrome: ‘like “Video Circus”, “Video Arena”. Do you know it? [….] It’s just torture and murder, no plot, no characters – very realistic. I think it’s what’s next’.  Masha offers the first hint that the Videodrome phenomenon has an explicit political dimension. She tells Max to leave Videodrome alone: ‘it is definitely not for public consumption’, she declares, ‘I think it’s dangerous, Max’. Max initially believes that Masha means the Videodrome signal is connected to organised crime: ‘The Mafia?’, he queries, ‘They do business’. ‘It’s more, how can I say, more political than that’, Masha tells him. Masha offers the first hint that the Videodrome phenomenon has an explicit political dimension. She tells Max to leave Videodrome alone: ‘it is definitely not for public consumption’, she declares, ‘I think it’s dangerous, Max’. Max initially believes that Masha means the Videodrome signal is connected to organised crime: ‘The Mafia?’, he queries, ‘They do business’. ‘It’s more, how can I say, more political than that’, Masha tells him.

Max’s first exposure to the Videodrome signal in Harlan’s office leaves him intrigued but visibly unfazed by the extreme content. Videodrome offers programming that is cheap, sensational and addictive: a winning formula for Max. ‘We never leave that room?’, Renn asks when Harlan first shows him the broadcast. ‘No. It’s for real sickos [….] for pervert’s only’, Harlan continues. ‘Absolutely brilliant’, Renn asserts, ‘I mean, there’s no production costs. You can’t take your eyes off it: it’s incredible realistic. Where do they get actors who can do this?’ ‘Oh, help me. I think he wants it’, Harlan says. (Renn might as well be talking about any of the ‘reality’ television shows that have become popular during the new millennium.) On The Rena King Show, Rena King asserts that Channel 83 ‘offers everything from softcore pornography to hardcore violence’ and asks Max why. Max begins by telling King and the show’s viewers that ‘it’s a matter of economics, Rena. We’re small: in order to survive, we have to give people something they can’t get anywhere else’. Having outlined the economic imperative behind the extreme content of Channel 83, for the first of several times in the film, Max also justifies the content of Channel 83 through referring to the principle of catharsis, arguing that his channel offers viewers a ‘harmless outlet for their fantasies, their sexual frustrations’. Later in the film, when Max describes the Videodrome broadcast to Masha and tells her ‘I think it’s what’s next’, she replies by asserting ‘Then God help us’. Max once again refers to the concept of catharsis to justify his interest in Videodrome: ‘Better on the TV than on the streets’, he says.  The Rena King Show also offers us the first chance to hear Brian O’Blivion’s philosophy. ‘The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye’, O’Blivion declares via the television monitor in the studio. ‘That’s why I refuse to appear on television except on television. Of course, O’Blivion is not the name I was born with: that’s my television name. Soon all of us will have special names, names designed to cause the cathode ray tube to resonate’. Like the narration of Cronenberg’s early short Stereo (1969) and the writings of post-structuralist thinker Jean Baudrillard, Brian O’Blivion’s rhetoric ‘is hyper-technologised but anti-rational; moebius-like in its evocation of a dissolute, spectacular reality’ (ibid.). The Rena King Show also offers us the first chance to hear Brian O’Blivion’s philosophy. ‘The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye’, O’Blivion declares via the television monitor in the studio. ‘That’s why I refuse to appear on television except on television. Of course, O’Blivion is not the name I was born with: that’s my television name. Soon all of us will have special names, names designed to cause the cathode ray tube to resonate’. Like the narration of Cronenberg’s early short Stereo (1969) and the writings of post-structuralist thinker Jean Baudrillard, Brian O’Blivion’s rhetoric ‘is hyper-technologised but anti-rational; moebius-like in its evocation of a dissolute, spectacular reality’ (ibid.).

For his part, initially Max believes the torture and murder in the Videodrome broadcast to be simulated, part of a broader narrative. ‘When does the plot start to unravel here?’, Max asks Harlan, ‘I mean, who is this black guy? Is he a prisoner?’ ‘There’s no plot’, Harlan tells Max Renn with slight exasperation, ‘It just goes on like that for an hour or more [….] Torture, murder, mutilation’. Later, Masha tells Max that ‘What you see on that show [Videodrome], it’s for real. It’s not acting. It’s “snuff” TV’. ‘Why do it for real?’, Max asks, ‘It’s easier and safer to fake it’. ‘Because it has something you don’t have, Max’, Masha responds, ‘It has a philosophy, and that is what makes it dangerous’. Masha appears to have some inside knowledge of Videodrome, so her assertion that the broadcast is ‘“snuff” TV’ may be taken at face value, but the revelation that Videodrome originates within Spectacular Optical and the broadcast is simply a device used to carry the signal which generates the hallucinations (and tumours) within its viewers also carries with it the suggestion that the ‘snuff’ footage is faked. Whether it is or not is unimportant, however: what is important is the suggestion that Max’s (and our) perception as to whether or not Videodrome is simulated (ie, whether or not it is ‘real’ or ‘faked’) continually destabilises Max’s (and, again, our) perception of the broadcast.  Cronenberg’s film defies the conventions of Hollywood narrative forms: Cronenberg gives us a protagonist, Max Renn, whose point of view guides the film, but who quickly finds himself to be in a state of cognitive confusion. Renn is the victim of hallucinations brought on by the Videodrome signal: we share his experience of these hallucinations. As such, the film’s point of view, driven by Renn’s, is unreliable; this forces the viewer to be increasingly active in their interpretation of the film as the narrative progresses. As Renn’s perception of the world around him is destabilised, so is ours: like Renn, we are unsure which events are ‘real’ and which events are a product of his hallucinations. However, the Baudrillardian ‘point’ seems to be that the simulation is indistinguishable from, and has in fact superseded the ‘reality’ it represents. In the tape that Bianca O’Blivion gives Max, Brian O’Blivion declares that ‘The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore television is reality, and reality is less than television’. From that perspective, whether or not the Videodrome footage is taken, within the film’s diegesis, as ‘real’ or ‘faked’ is a non-issue: what matters is the audience’s perception of it and the impact it has on its viewers (ie, the tumours and hallucinations). As Bianca O’Blivion declares, ‘After all, there is nothing real outside our perception of reality. You can see that, can’t you?’ Cronenberg’s film defies the conventions of Hollywood narrative forms: Cronenberg gives us a protagonist, Max Renn, whose point of view guides the film, but who quickly finds himself to be in a state of cognitive confusion. Renn is the victim of hallucinations brought on by the Videodrome signal: we share his experience of these hallucinations. As such, the film’s point of view, driven by Renn’s, is unreliable; this forces the viewer to be increasingly active in their interpretation of the film as the narrative progresses. As Renn’s perception of the world around him is destabilised, so is ours: like Renn, we are unsure which events are ‘real’ and which events are a product of his hallucinations. However, the Baudrillardian ‘point’ seems to be that the simulation is indistinguishable from, and has in fact superseded the ‘reality’ it represents. In the tape that Bianca O’Blivion gives Max, Brian O’Blivion declares that ‘The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore television is reality, and reality is less than television’. From that perspective, whether or not the Videodrome footage is taken, within the film’s diegesis, as ‘real’ or ‘faked’ is a non-issue: what matters is the audience’s perception of it and the impact it has on its viewers (ie, the tumours and hallucinations). As Bianca O’Blivion declares, ‘After all, there is nothing real outside our perception of reality. You can see that, can’t you?’

Videodrome was cut for an ‘R’ rating in the US, and this ‘R’ rated version of the film was the one that was shown in UK cinemas. (The ‘R’ rated cut trimmed the Samurai Dreams footage and toned down some of the Videodrome broadcast footage, as well as trimming much of the violence and shortening the sequence in which Max pierces Nikki’s ears during their love-making.) Released on videocassette by CIC in 1987, the film was further cut by the distributors before being submitted to the BBFC for video classification: another three minutes of material was excised, and much of this footage was from the scenes in which Nikki’s masochism is foregrounded (for example, when she asks Max to cut her with his knife). The unrated cut was broadcast on Sky during the early 1990s and was also issued on LaserDisc during that period (though this doesn’t appear to have been submitted to the BBFC). However, the subsequent UK DVD and Blu-ray releases from Universal (in 2002 and 2011, respectively) contained the ‘R’ rated cut (though reinstated the material pre-cut by the distributor for the 1987 videocassette).    Arrow’s new Blu-ray release thankfully contains the complete unrated cut, and runs for 88:39 mins.

Video

The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Videodrome is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.  For all intents and purposes, the presentation is identical to the presentation of the film that has been released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in the States. Both are based on the same source: a scan of a 35mm interpositive that was supervised by the film’s director of photography, Mark Irwin, and approved by Cronenberg. (Naturally both the Criterion and Arrow discs have a different encode, but the experience of viewing both presentations is identical.) The previous European Blu-ray releases by Universal (of the ‘R’ rated cut) were in the same aspect ratio but opened up the framing slightly in a way never intended by either Cronenberg nor the Irwin. The slightly tighter compositions seen in the Arrow and Criterion Blu-ray presentations are in line with the intentions of both. For all intents and purposes, the presentation is identical to the presentation of the film that has been released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in the States. Both are based on the same source: a scan of a 35mm interpositive that was supervised by the film’s director of photography, Mark Irwin, and approved by Cronenberg. (Naturally both the Criterion and Arrow discs have a different encode, but the experience of viewing both presentations is identical.) The previous European Blu-ray releases by Universal (of the ‘R’ rated cut) were in the same aspect ratio but opened up the framing slightly in a way never intended by either Cronenberg nor the Irwin. The slightly tighter compositions seen in the Arrow and Criterion Blu-ray presentations are in line with the intentions of both.

The presentation has the texture of 35mm film, with a lovely organic appearance throughout the film. The rich colour reproduction is evident from the opening titles (deep orange text on a black screen) and particularly in the red light-bathed scenes depicting Max and Nikki watching Videodrome in Max’s apartment. The presentation handles the mixed media footage (for example, the Videodrome broadcast and the footage of the Samurai Dreams programme, shot on one-inch tape) very well too. Some edge enhancement and haloing artifacts seem to be present from time to time, but it’s not too distracting. The focal lengths used in the shoot appear to be naturalistic (35mm or 50mm, seemingly), giving strong depth of field within the original photography (for example, the deep focus staging of Max in his apartment) that is communicated nicely in this home video presentation. Plenty of fine detail is on display too. Excellent contrast levels result in a pleasing, very nicely balanced image.    NB. Some large screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track (in English, naturally). This is deep, resonant and rich: Howard Shore’s pulsing, strange and haunting electronic score resonates like a church organ. The track, though not a ‘showy’ one by any means, evidences excellent range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The release is a two-disc set including two Blu-ray discs. Retail copies also come with a lavish hardback book, running to a hundred pages, which includes some new writing about the film (by Justin Humphreys; Brad Stevens – who explores the different cuts of the picture; Caelum Vatnsdal – focusing on Cronenberg’s early films) alongside pre-existing extracts from the book Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Tim Lucas also offers a tribute to recently deceased special effects man Michael Lennick; and the whole shebang is rounded out by the inclusion of some beautiful stills and details about the transfer. DISC ONE (Blu-ray):  This disc includes the film, with an optional audio commentary by Tim Lucas. Lucas, who was on the set of Videodrome, offers a thorough and carefully-prepared commentary (as with Lucas’ other commentaries, this one seems thoroughly scripted), delivering a discussion of the film that is rooted in first-person experiences. This disc includes the film, with an optional audio commentary by Tim Lucas. Lucas, who was on the set of Videodrome, offers a thorough and carefully-prepared commentary (as with Lucas’ other commentaries, this one seems thoroughly scripted), delivering a discussion of the film that is rooted in first-person experiences.

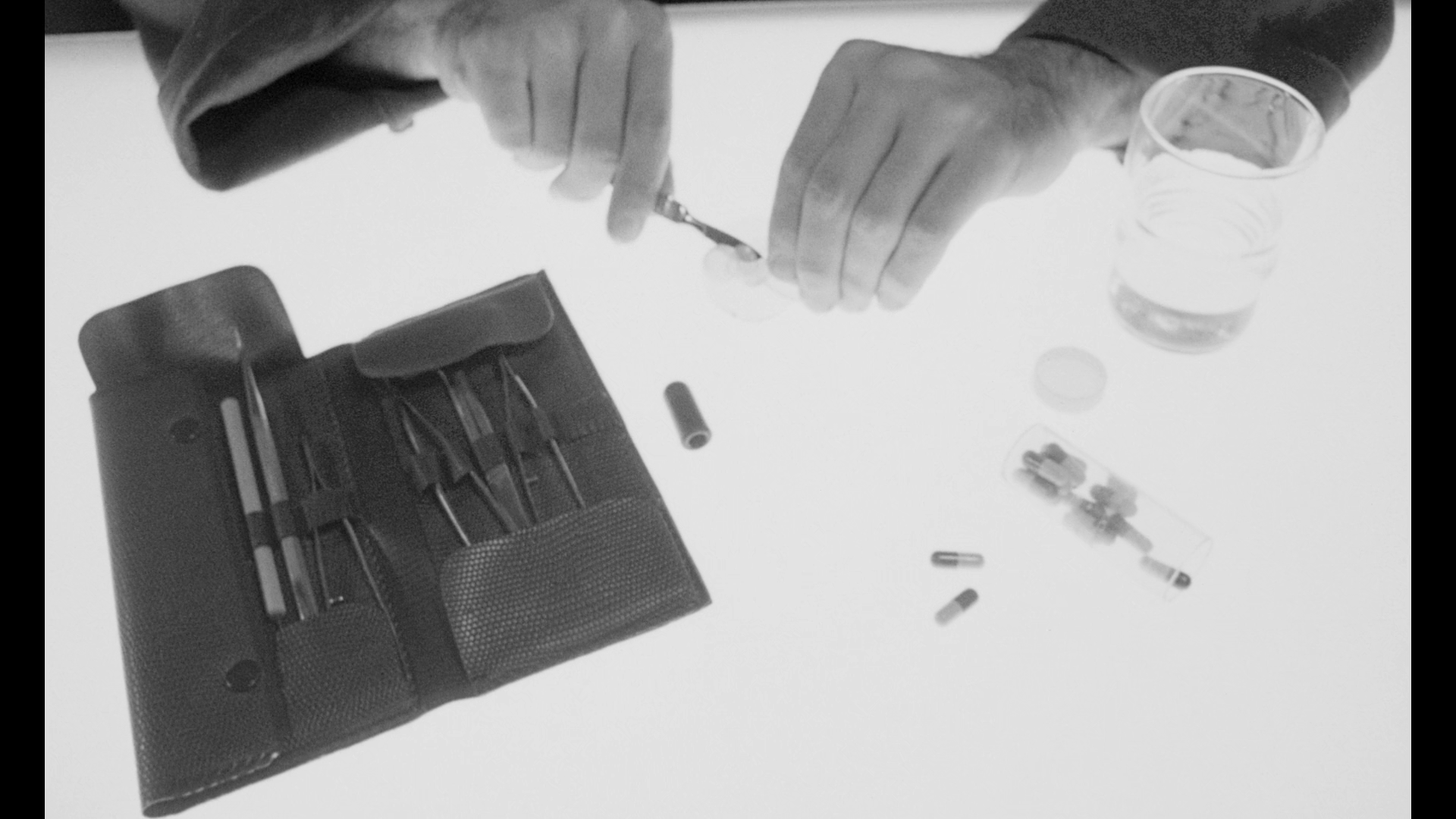

Alongside this, the disc includes: ‘David Cronenberg and the Cinema of the Extreme’ (21:04). This featurette, originally broadcast on BBC2 in 1997 prior to a screening of Videodrome, features Cronenberg interviewed about his films alongside George A Romero and Alex Cox. It’s an excellent little piece that is illustrated with some clips from the films under discussion. ‘Forging the New Flesh’ (27:44). Presented (and directed) by Videodrome’s special effects supervisor Michael Lennick, and originally made for inclusion on the Criterion Collection’s DVD release of the film, this featurette focuses on the production of the film from the perspective of the makeup effects team. It includes interviews with Rick Baker, Bill Sturgeon, Frank C Carere and location manager David Coatsworth, interspersed with archival interviews from the film’s production and behind-the-scenes footage. ‘Fear on Film’ (25:40). Made in 1982, this round table discussion about the horror film generally is hosted by Mick Garris and features input from Cronenberg, John Carpenter and John Landis. The participants talk about their work in some detail, especially the battles they have had with censorship bodies. Carpenter and Cronenberg also discuss the two films that at the time of the interview, they were still making: Videodrome and Carpenter’s remake of The Thing. ‘Samurai Dreams’ with commentary by Michael Lennick (4:47). Presented here is all of the footage shot for Hiroshima Video’s Samurai Dreams series within Videodrome, filmed on one-inch tape. Lennick provides commentary over this, talking about the production of the footage.  Helmet Camera Test with commentary by Michael Lennick (4:45). Here, we can view the various tests produced for use in the sequence in which Convex places on Max the helmet which, Convex claims, can record Max’s hallucinations. Lennick once again provides commentary over this footage, discussing how the effects were achieved. Helmet Camera Test with commentary by Michael Lennick (4:45). Here, we can view the various tests produced for use in the sequence in which Convex places on Max the helmet which, Convex claims, can record Max’s hallucinations. Lennick once again provides commentary over this footage, discussing how the effects were achieved.

Why Betamax (1:11). Lennick explains the reasons why Betamax was used, rather than VHS, as the videocassette format within the film: principally owing to the size of the cassettes, which made it easier to achieve the effect in which a tape is inserted into Max’s stomach. Promotional Featurette (7:51). This is an EPK made when Videodrome was in production. Made by Mick Garris, the featurette includes interviews with Cronenberg, James Woods, Deborah Harry and Rick Baker, interspersed with footage from the production of the film. In this regard, there is some overlap with the footage in the ‘Forging the New Flesh’ featurette. Interviews: - Mark Irwin (26:27). In this new interview, Irwin reflects on his career as a director of photography and talks specifically about his work with Cronenberg, which began with Fast Company in 1979. Irwin talks in detail about the photography within Videodrome. This is an utterly superb interview that offers substantial insight into the film’s aesthetic. - Pierre David (10:16). David, who produced a number of Cronenberg’s films, offers comments in this newly-produced interview which largely focus on the relationship between this film and Scanners (and the contrast between both the experience of work on the two pictures and their reception). - Dennis Etchison (16:45). This fascinating interview is with the author of the novelisation of Videodrome, which differs quite substantially from the film in some places. Etchison talks about the difficulties in adapting such an unusual script. ‘Camera’ (2000) (6:42). This short film, directed by Cronenberg for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Toronto Film Festival, is shot on a mixture of digital video and 35mm film. It features Leslie Carlson playing a has-been actor who, in a monologue, reflects sadly on the state of cinema. It’s a short film that is very much about our relationship with technology. ‘Pirated Signals: The Lost Broadcast’ (25:48). Here we are presented with the footage included in the American television cut of the film, which trimmed back some of the more explicit material within Videodrome but includes some narrative material (and new opening and closing titles) that was eliminated from the final theatrical cut of the feature. This material clarifies some of the narrative events in a way that, if one watches the American television cut in its entirety, undermines the film’s ambiguous nature – and the picture’s enigmatic quality is arguably its greatest strength. Some of the material included here is simply extensions of scenes already included in the theatrical cut of Videodrome, but there are some alternate scenes too. For example, the scene in which Max is taken to Spectacular Optical by limousine: in the theatrical cut of the film, he rides alone and watches a video by Barry Convex; in the footage from the television cut of the picture presented in this extra, Max enters the limousine to find Nikki Brand seated inside. The footage has been sourced from a tape. Trailers (4:35). DISC TWO (Blu-ray): David Cronenberg’s Early Works:  - ‘Transfer’ (6:27). This 1966 short introduced Cronenberg’s focus on psychoanalysis, a topic that flows throughout a number of his films – most obviously The Brood (1979) and the more recent A Dangerous Method (2011). It’s a comic piece which features a psychoanalyst (Mart Ritts) in self-imposed exile (the film opens with the psychoanalyst brushing his teeth on a snow-covered field), who is surprised by one of his patients, Ralph (Rafe McPherson). Ralph wishes to continue his therapy sessions – against the desire of the psychoanalyst, who is trying to escape from the ‘trap’ of psychoanalysis (and, more generally, communication of any kind). (‘Communication was the original sin’, the psychoanalyst says, ‘Psychoanalysis could be a miracle if it weren’t for the sick mind. I had to get away’.) - ‘Transfer’ (6:27). This 1966 short introduced Cronenberg’s focus on psychoanalysis, a topic that flows throughout a number of his films – most obviously The Brood (1979) and the more recent A Dangerous Method (2011). It’s a comic piece which features a psychoanalyst (Mart Ritts) in self-imposed exile (the film opens with the psychoanalyst brushing his teeth on a snow-covered field), who is surprised by one of his patients, Ralph (Rafe McPherson). Ralph wishes to continue his therapy sessions – against the desire of the psychoanalyst, who is trying to escape from the ‘trap’ of psychoanalysis (and, more generally, communication of any kind). (‘Communication was the original sin’, the psychoanalyst says, ‘Psychoanalysis could be a miracle if it weren’t for the sick mind. I had to get away’.)

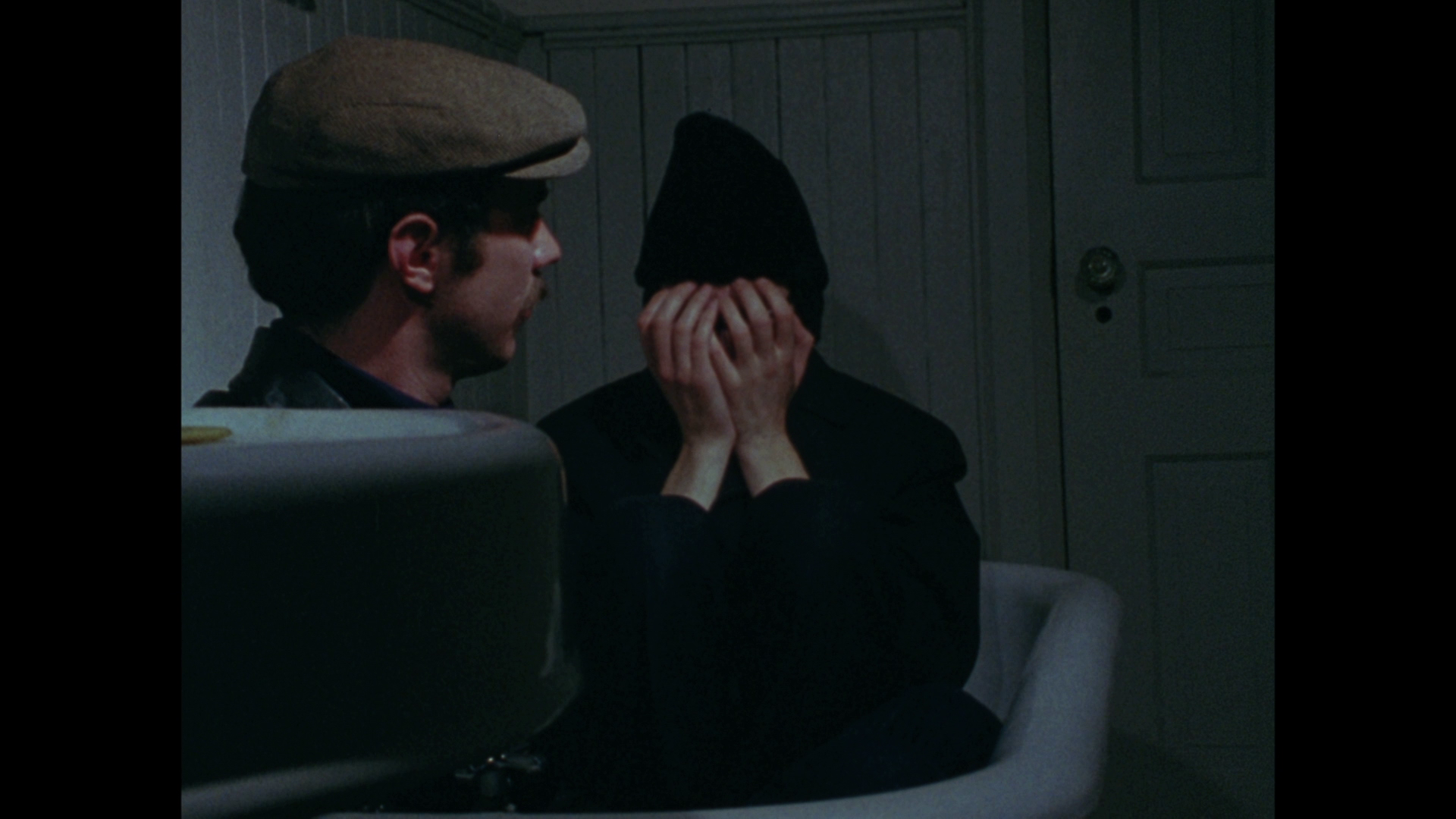

The film, shot on 16mm and in colour, was produced in a rudimentary manner. The image here is in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio. It’s a fine presentation. Softness in some shots suggests damage to the materials, but on the whole the image is clean and clear, with balanced contrast and the natural grain one would expect from material shot on 16mm. Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. The sound was recorded ‘live’ and is distorted by the wind – and so some lines of dialogue are difficult to hear. Optional English subtitles are included.  - ‘From the Drain’ (12:48). Made by Cronenberg in 1967, this short film focuses on two men who are seated in a bathtub in what the dialogue suggests is a ‘disabled war veterans’ treatment centre’. Vague references to ‘the war’ suggest that the two men are veterans of a conflict, who return to the centre to meet with others of their kind. One of the two men insists that he fears the ‘Tendrils [….] From the drain’. It’s an enigmatic, comic piece, structured along the lines of Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot; the concept of tendrils which appear from the drain initially sounds absurd, the product of the rantings of a lunatic, but the tendrils inevitably appear towards the end of the film, killing one of the men. The dialogue is farcical, but there’s an unsettling undercurrent that bubbles beneath the text; classical music, played on a harp, acts as a counterpoint to what we see on the screen (and underscores how potent, but how subtle, the use of music in Cronenberg’s films often is). - ‘From the Drain’ (12:48). Made by Cronenberg in 1967, this short film focuses on two men who are seated in a bathtub in what the dialogue suggests is a ‘disabled war veterans’ treatment centre’. Vague references to ‘the war’ suggest that the two men are veterans of a conflict, who return to the centre to meet with others of their kind. One of the two men insists that he fears the ‘Tendrils [….] From the drain’. It’s an enigmatic, comic piece, structured along the lines of Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot; the concept of tendrils which appear from the drain initially sounds absurd, the product of the rantings of a lunatic, but the tendrils inevitably appear towards the end of the film, killing one of the men. The dialogue is farcical, but there’s an unsettling undercurrent that bubbles beneath the text; classical music, played on a harp, acts as a counterpoint to what we see on the screen (and underscores how potent, but how subtle, the use of music in Cronenberg’s films often is).

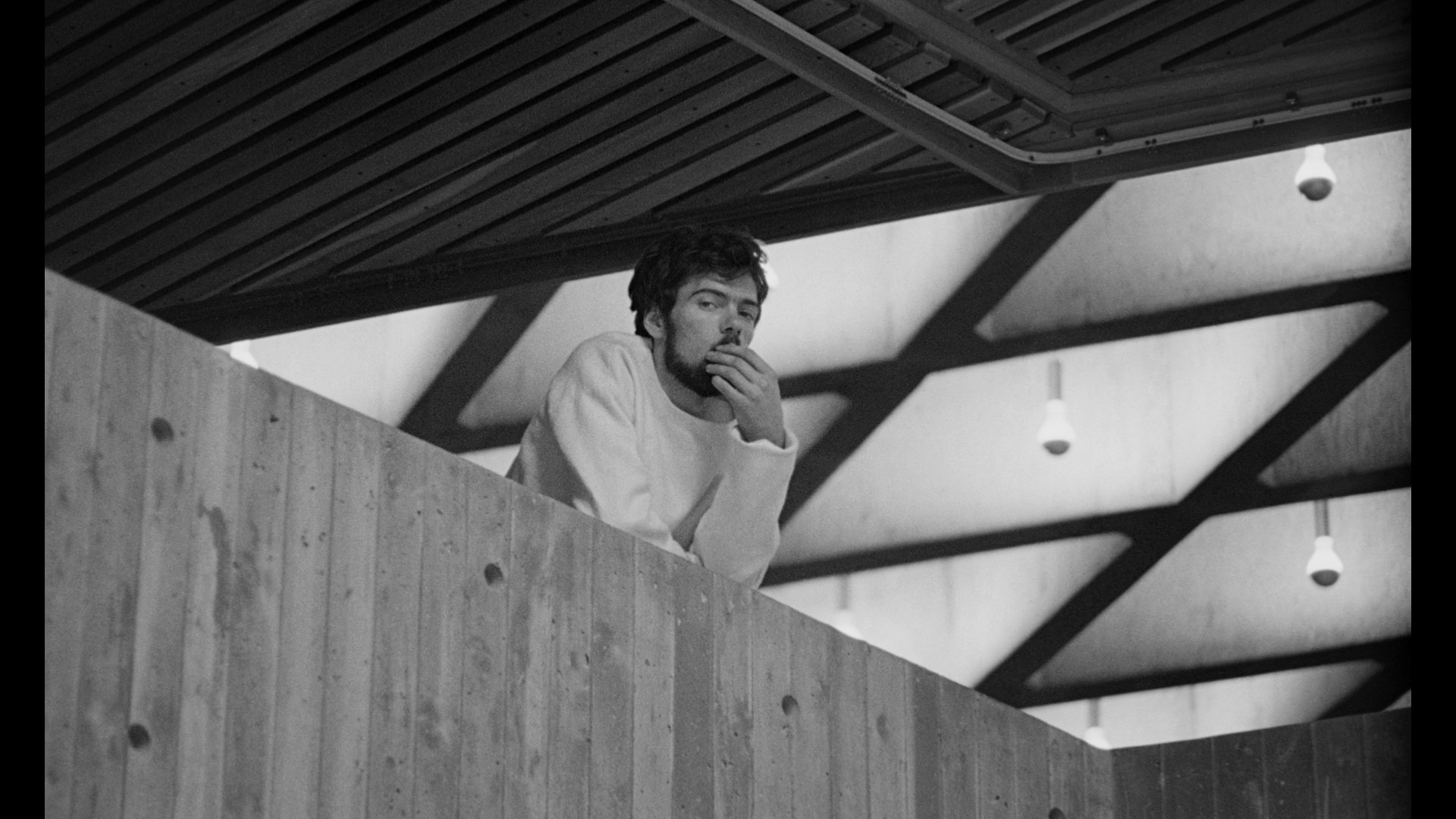

The film, again shot on 16mm, is presented here in the 1.33:1 ratio. It’s a fine, balanced image with good contrast and strong detail evident. It also has the organic appearance of film. The sound, again recorded live, is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is more polished and ‘clean’ than its predecessor, but this is largely owing to shooting under more controlled circumstances (ie, in a bathroom rather than in a field). Again, optional English subtitles are provided.  - ‘Stereo’ (62:43). In Stereo, the themes of Cronenberg’s later films begin to take a more defined shape. The film is framed as a documentary, including fake credits that identify it as such. Shot on 35mm film, the film is silent except for the voices of a number of narrators, all of whom speak in a cold, clinical language to explain to the viewer what is taking place onscreen. What they describe is an experiment in ‘induced telepathy’ involving eight subjects at the Canadian Institute for Erotic Inquiry, initiated by Dr Luther Stringfellow, a mysterious scientific outlaw whose presence, though he never appears on screen or guides the narration, is felt throughout. The eight subjects have had surgery conducted upon them in order to provide them with ‘telepathic abilities’. ‘Omnisexual’ sexual encounters have been engineered between the subjects as a means of facilitating the further development of their telepathic skills. - ‘Stereo’ (62:43). In Stereo, the themes of Cronenberg’s later films begin to take a more defined shape. The film is framed as a documentary, including fake credits that identify it as such. Shot on 35mm film, the film is silent except for the voices of a number of narrators, all of whom speak in a cold, clinical language to explain to the viewer what is taking place onscreen. What they describe is an experiment in ‘induced telepathy’ involving eight subjects at the Canadian Institute for Erotic Inquiry, initiated by Dr Luther Stringfellow, a mysterious scientific outlaw whose presence, though he never appears on screen or guides the narration, is felt throughout. The eight subjects have had surgery conducted upon them in order to provide them with ‘telepathic abilities’. ‘Omnisexual’ sexual encounters have been engineered between the subjects as a means of facilitating the further development of their telepathic skills.

As the film begins, one of the subjects (Ron Mlodzik) arrives at the institute via helicopter and explores its grounds. An unsettling series of shots juxtapose the figure of the subject with the Brutalist architecture of the institute itself (actually the Scarborough College campus at the University of Toronto). We are told that some of the subjects are mute owing to ‘large potions of the speech centres in [their] brains [being] obliterated’ by the surgery. Like O’Blivion’s comments in Videodrome (discussed above), the narration in Stereo uses the cold, clinical discourse of science to talk about a subject that is utterly unscientific: to reference the quote from Scott Bukatman used above, like the work of Baudrillard (or the ramblings of Brian O’Blivion) the narration within Stereo is ‘hyper-technologised but anti-rational’ – giving the sense of the lunatics having taken over the asylum. There is juxtaposition of the cold, clinical guiding voice of the film’s various narrators, using the heavy rhetoric of science (but also incorporating ‘unscientific’ topics such as telepathy and ESP) with the cold alienation of the subjects – set against the equally cold and alienating modernist architecture of the institute. The subjects flirt and play, and homosexual and heterosexual relationships are asserted, but ultimately they all feel like prisoners.  The focus on ESP and telepathy induced by medicine has clear parallels with some of Cronenberg’s later work (for example, Scanners), and the use of alienating modernist architecture is something that also crops up in many of Cronenberg’s later films – in the use of Starliner Towers as the setting for Shivers, for example. Discussion in the narration of one of the test subjects who used a hand drill to ‘wound himself in the forehead’ also has resonance with Scanners, in terms of Darryl Revok’s (Michael Ironside) injury – sustained as a result of a form of self-trepanation. The concept of behaviour modification through the ‘appliance of science’ is something which recurs throughout Cronenberg’s work (for example, in the radical skin graft technique in Rabid, the development of the parasite in Shivers, the ‘psychoplasmics’ of the Somafree Institute in The Brood, and Spectacular Optical’s activities in Videodrome). The focus on ESP and telepathy induced by medicine has clear parallels with some of Cronenberg’s later work (for example, Scanners), and the use of alienating modernist architecture is something that also crops up in many of Cronenberg’s later films – in the use of Starliner Towers as the setting for Shivers, for example. Discussion in the narration of one of the test subjects who used a hand drill to ‘wound himself in the forehead’ also has resonance with Scanners, in terms of Darryl Revok’s (Michael Ironside) injury – sustained as a result of a form of self-trepanation. The concept of behaviour modification through the ‘appliance of science’ is something which recurs throughout Cronenberg’s work (for example, in the radical skin graft technique in Rabid, the development of the parasite in Shivers, the ‘psychoplasmics’ of the Somafree Institute in The Brood, and Spectacular Optical’s activities in Videodrome).

Compared with Cronenberg’s earlier shorts, Stereo is shot beautifully, in crisp monochrome; the space inside the institute is often distorted through the use of wide-angle lenses, and Cronenberg makes strong use of tracking shots to suggest the alienating relationship/s between the characters and their environment. The photography enhances the prison-like qualities of the locaton. This presentation of the film is based on a restoration by the Criterion Collection from a 35mm fine grain element. The 1080p presentation takes up approximately 17Gb of space. The film, shot in monochrome on 35mm stock, is presented in the 1.66:1 screen ratio. Contrast is nicely-balanced throughout, with strong mid-tones on display; and there is plenty of detail evident in the image. There is some damage here and there (what appear to be density fluctuations in the emulsions), but on the whole this is a beautiful presentation. In terms of audio, the film is presented with a LPCM 1.0 mono track; depth and range is evident, and it is clean and clear throughout. Optional English subtitles are included.     - ‘Crimes of the Future’ (62:37). The film is very much a companion piece to Stereo and stars Ron Mlodzik as Adrian Tripod, the current director of the House of Skin. Tripod narrates the film, telling us of the origins of the House of Skin as a place where ‘wealthy patients’ were treated for ‘severe pathological skin conditions induced by contemporary cosmetics’. However, as the film begins ‘the house is undeniably in decline’, abandoned by its founder Anton Rouge – another absent outlaw scientist, like Luther Stringfellow in Stereo. - ‘Crimes of the Future’ (62:37). The film is very much a companion piece to Stereo and stars Ron Mlodzik as Adrian Tripod, the current director of the House of Skin. Tripod narrates the film, telling us of the origins of the House of Skin as a place where ‘wealthy patients’ were treated for ‘severe pathological skin conditions induced by contemporary cosmetics’. However, as the film begins ‘the house is undeniably in decline’, abandoned by its founder Anton Rouge – another absent outlaw scientist, like Luther Stringfellow in Stereo.

Tripod, clad in black with unusual spectacles, is a striking figure who prowls through the House of Skin – once again an alienating modernist building (or rather, series of buildings). In the absence of Rouge, the seemingly enormous House of Skin has only one patient, a young man who secretes a mysterious substance ‘which we call “Rouge’s Foam”’. Tripod’s authority has been undermined: he is as much a prisoner as the patient the House of Skin is treating. ‘Somehow, without my comprehension of it’, Tripod narrates, ‘it [the House of Skin] has fallen into the hands of my two sullen interns. Their purposes are entirely opaque to me, as are the purposes of so many others’. When the institute’s sole patient expires, Tripod transfers his work to the Institute for Neo-Venereal Disease. The presentation of Crimes of the Future, which like Stereo occupies approximately 17Gb of space on the disc, is based on a new 4k scan of the negative by Arrow. Shot on 35mm and in colour, Crimes of the Future is presented in the 1.66:1 screen ratio. Contrast and colour reproduction are good. (There’s some flattening of contrast in some scenes, but this is a product of inconsistent light conditions in the shooting of the film – with outdoor scenes shot on brightly-lit days, bearing harsh shadows and bold exposures, set against footage shot with more muted light.) Again, as with Stereo the photography tends to favour short focal lengths with strong depth of field – and this is communicated very nicely in this presentation. Plenty of detail is on display throughout. Audio is once again presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track which is clear throughout, and is again accompanied by optional English subtitles.    NB. Some large screen grabs from all four short films are included at the bottom of this review, below the screen grabs taken from the main feature. Interview with Kim Newman (16:51). In this interview, Kim Newman discusses Cronenberg’s early short films and talks about the differences between the horror auteurs of the 1970s and emerging horror filmmakers today, situating the work of Cronenberg and his contemporaries within the context of the rise in independent filmmaking during the 1960s and 1970s. In particular, Newman compares Cronenberg’s early work with Tobe Hooper’s avant garde first feature Eggshells (1969) (which is included in Arrow’s superb Blu-ray release of Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2, 1986).

Overall

David Cronenberg’s Videodrome is an extraordinary picture, undoubtedly one of the best genre films of the 1980s. The film offers a strong criticism of our media-driven society. Tapped deeply into the zeitgeist of the era in which it was made, the film feels remarkably prescient today – and it’s easy to apply the ideas within the film to the digital era. David Cronenberg’s Videodrome is an extraordinary picture, undoubtedly one of the best genre films of the 1980s. The film offers a strong criticism of our media-driven society. Tapped deeply into the zeitgeist of the era in which it was made, the film feels remarkably prescient today – and it’s easy to apply the ideas within the film to the digital era.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release is exemplary. Cronenberg fans will most likely wish to hang onto the Criterion Collection Blu-ray release as well as purchasing this new Blu-ray release from Arrow, owing to the inclusion of some unique contextual material on both releases (the Criterion disc includes two fascinating audio commentaries by Cronenberg and Mark Irwin, and James Woods and Deborah Harry). However, taken on its own terms Arrow’s release contains the best array of contextual material – thanks in large part to the inclusion of Cronenberg’s early films, including the marvelous pairing of Stereo and Crimes of the Future in HD. This is an absolutely superb release and comes with the highest recommendation. References: Bukatman, Scott, 2007: ‘Who Programs You? The Science Fiction of the Spectacle’. In: Redmond, Sean (ed), 2007: Liquid Metal: The Science Fiction Reader. London: Wallflower Press: 228-38 Burton, Lyndsey, 2013: ‘Low income and digital exclusion’. [Online.] http://www.poverty.ac.uk/editorial/low-income-and-digital-exclusion Date accessed: 12 August, 2015

Transfer:

From the Drain:

Stereo:

Crimes of the Future:

|

|||||

|