|

|

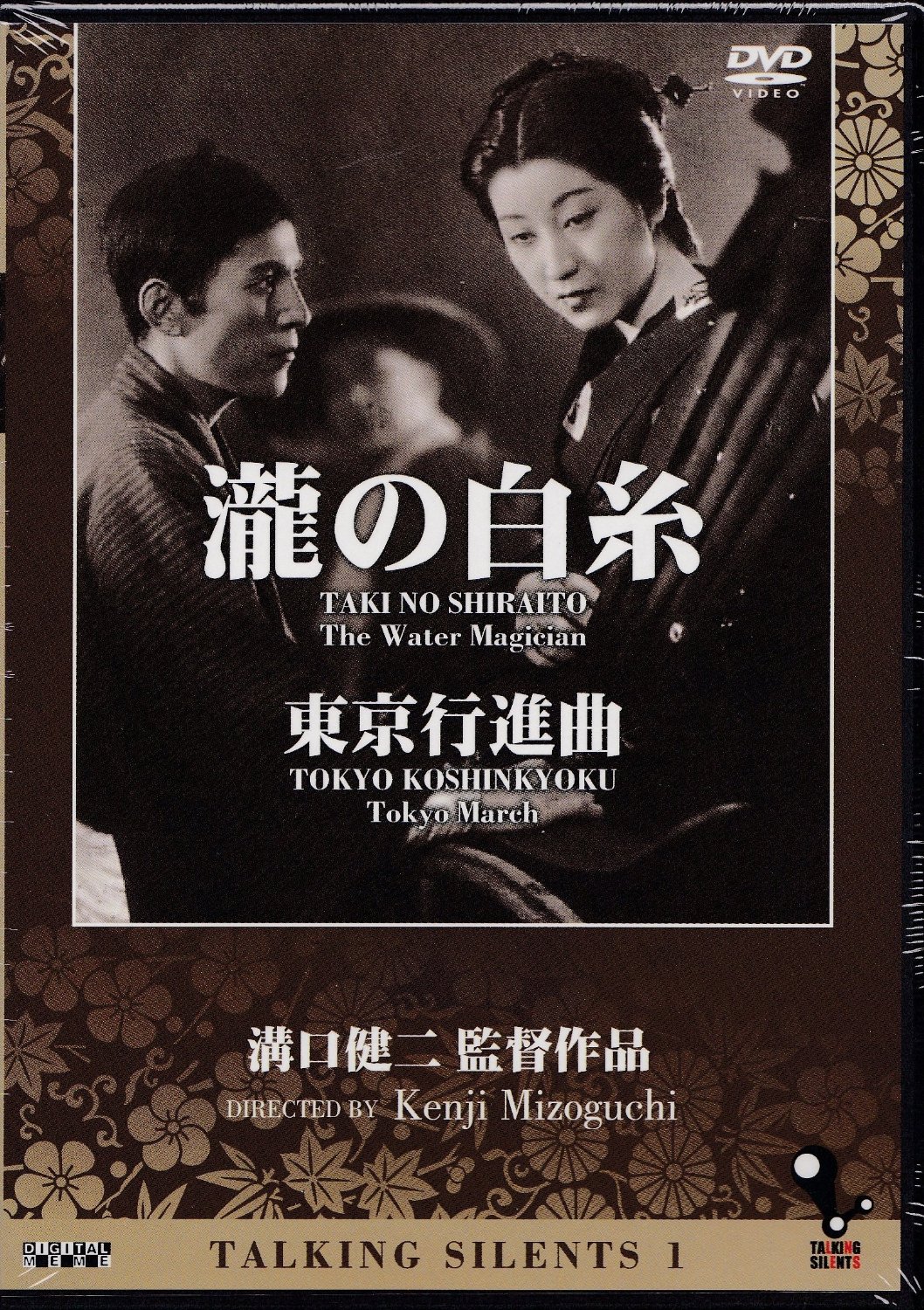

Tokyo March AKA Tôkyô kôshinkyoku

R0 - Japan - Digital Meme Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (18th August 2015). |

|

The Film

“Talking Silents 1” features two films directed by Kenji Mizoguchi: “The Water Magician” (1933) and “Tokyo March” (1929) “The Water Magician”(1933) A traveling performance troupe comes to a local festival, including the beautiful and popular performer named “Taki no Shiraito” (played by Takako Irie), literally meaning “White Thread of the Waterfall” who is a water juggler: using paddles, water fountains, and a few tricks up the sleeve to show the townsfolk a grand performance. But she is smiling not because of the performance. She is smiling because she is reminiscing about a chance encounter 3 days prior: En route to the next town by horse and carriage, Shiraito and a few other passengers are outrun by a rickshaw. Not to be outdone, the carriage driver speeds up only to break an axle, stranding the carriage. Knowing that the female performer passenger must get to the next town as soon as possible, he takes a horse and the two ride together into town, comically stranding behind the male passengers of the carriage. Shiraito apparently fainted along the way, and when she awakens the driver is nowhere to be found, as he had already returned to the stranded carriage, but accidentally leaves behind his law textbook . Like a Cinderella story in reversed-gender roles, Shiraito becomes completely intrigued by the carriage driver, in which she only knows his nickname, “Kin-san” (played by Tokihiko Okada). 3 days pass by, and Shiraito dreams of meeting Kin-san again, to return his law textbook and to follow her heart’s calling. Shiraito notices a man sleeping on a bridge, which she thinks is one of her drunken troupe members, but it happens to be the carriage driver, Kin-san. Or former carriage-driver, as he states that he was fired for vehicle damage and negligence. Broke and out of work, his dream of studying to become a lawyer had faded away. Shiraito listens to his story and decides with her heart to help him achieve his dream. She gives Kinya 30 yen to travel to Tokyo to find a way towards his dream and also promises to send him money, a little from each of her paychecks to help him pay for the law school tuition. Kinya tells her that he is forever indebted, and promises to fulfill his dream, which is also now Shiraito’s dream. But all is not a Cinderella tale. With summer being an excellent time for the troupe having many festivals around the country, the winter season is the opposite, with the troupe struggling to find places they can perform. Shiraito struggles with money to send to Kinya, who even at one point says he understands the hardship and is willing to postpone his studies and work harder to earn money for school himself. Shiraito, desperate to not let her promise down, talks to rich men for help and even a locally infamous loan shark for money to borrow. But what happens to Shiraito in her attempts to get enough money turns dark, as she becomes a suspect for something unthinkable: murder. “The Water Magician” was directed by Kenji Mizoguchi, 10 years after he debuted as a director. With a pace of about 5 to 10 films per year during the silent era, Mizoguchi had quite a resume by the time he had made “The Water Magician” in 1933. The theme of the self-sacrificing woman is a key point to many of Mizoguchi’s films, as it is here. Mizoguchi’s older sister had to sacrifice much of her life to help her family and her younger brothers, and what she had to go through profoundly influenced the way he portrayed female characters in his films. As mentioned prior, the Cinderella parallels are evident: The horse carriage having to travel at a faster speed, the law textbook/glass shoe being left behind, the short time span between the man and the woman, the famous star/royal Prince falling in love and continuing the search for the mysterious person. “Cinderella” is a fantasy story filled with magic and a happy ending after a long sacrifice under tough conditions for the title character. The perils the character Shiraito goes through is harsh, as the quite innocent and good hearted woman gets swept into absolutely horrible situations, not because of her mistakes, but because circumstances were cruel. “The Water Magician” was originally written as a short story by novelist Kyoka Izumi with the title “Giketsu kyoketsu” in the Yomiuri Newspaper in 1894. The stage play and the movie adaptations were retitled as “Taki no Shiraito”. The Mizoguchi adaptation was not the first. It was first made into a film in 1915, then in 1933 by Mizoguchi, in 1937 (the first talkie version, directed by Masahiro Makino), 1946, 1952, and last in 1956, being a very popular story over the years. “The Water Magician” is arguably a fantasy story. The naïveté of the title character falling in love with a man instantly after a chance encounter and then deciding to send him money for school after every paycheck sounds like the ultimate naïve innocent preyed on by a scammer if this were the 21st century in Japan or anywhere else. But this is in 1930’s Japan. Marriages were almost always arranged. Marriage did not equate as “love” but rather as a necessity for societal reasons. There was social hierarchy with class structure. Men and women did not mingle or date. And a man and a woman definitely could not spend a night talking on a bridge under the moonlight, as featured in the film. In films such as “Speed” (1994) in which the characters of Annie and Jack fall in love under the extreme circumstance on a speeding bus, “Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro” (1979) in which Clarisse is rescued by Lupin during the car chase, or “Back to the Future Part III” (1990) in which Doc Brown rescues Clara Clayton from her runaway carriage, the films show that it doesn’t take weeks or years of courtship to fall in love. You just need a circumstance like a runaway vehicle and a person to rescue you, which does have some real-life plausibility. As for the sending of the money, the trust between people and the honor of promise and gratitude was very important in Japanese culture. Although it is still important culturally, in these modern times if a person were to send money monthly to someone they just met, there would be some suspicion around. But we must look at the story and the film in a historical point of view rather than to compare “then and now”. Mizoguchi directed the film absolutely brilliantly. The opening scenes of the festival with tracking shots move the audience directly into the story. The comedic moments are later balanced with intense heartbreak and suspense, pulling all stops for emotional appeal, which he was best known for doing in many of his later sound films such as “The Life of Oharu” (1952), “Sansho the Bailiff” (1954), and “Street of Shame” (1956) which was his final film released a few months before his death at the age of 58. With most of Mizoguchi’s silent films being considered lost, it is hard to pinpoint exactly when he solidified his style, but “The Water Magician” certainly shows many of his trademarks. Lead actress Takako Irie does an absolutely wonderful job as Shiraito. Irie was only 22 at the time of production but was already a powerful star in films, by starting her own “Irie Productions” company and “The Water Magician” being the first film produced by the company. She starred in about 10 films for Mizoguchi in her film career, including “Tokyo March”. She continued into sound films, featured in films such as “The Most Beautiful” (1944) and “Sanjuro” (1962) both directed by Akira Kurosawa, and some “kaidan” horror films in the 1950s. She mostly retired from acting, but appeared in a few cameo appearances late in her career. She died in 1995 at the age of 83 from pneumonia. Actor Tokihiko Okada was quite the handsome matinee star at the time, but did not live long enough to see it continue. Okada worked with both Mizoguchi and for Yasujiro Ozu for 5 films each, including Ozu’s films “That Night’s Wife” (1930) and “Tokyo Chorus” (1931). He was never able to transition to sound film, as he died in 1934 at the age of only 30 years old, from tuberculosis. “The Water Magician” presented here runs 99:35. Researching about the runtime and the cut status proved quite difficult, as most silent films in Japan from the time are considered lost, and records of their runtimes and cut status are sometimes lost as well. Certain sequences made me believe that this particular print was missing some sequences. For example, the scene in which Shiraito is suddenly unconscious for unspecified reasons, the sudden scene transition from the train jump to the inn, and also the abrupt ending. The National Film Center (NFC) in Tokyo, Japan has a 35mm theatrical print of “The Water Magician” in their archives running 105 minutes, a full 5 minutes longer than this DVD. IMDB states the runtime is 110 minutes, which the source is unknown. “Tokyo March”(1929) Taking place in Shinjuku, Tokyo, a rebellious young man named Yoshiki (played by Koji Shima) plays tennis with his friend. After their tennis ball bounces out of the court and lands below down a little hill, he sees a young woman, and is immediately smitten by her beauty. Yoshiki tries, but is not able to find the woman, in which he only knows her name, “Michiyo” (played by Shizue Natsukawa). Months later, Yoshiki starts working in a company. Michiyo becomes a Geisha in Shimbashi. Coincidentally Yoshiki’s father Mr. Fujimoto (played by Eiji Takagi) goes to Shimbashi to be entertained by Michiyo, now named Orie as her Geisha name. But is it more than just coincidence that Mr. Fujimoto is meeting her? “Tokyo March” marks the first time a song and a film were marketed together in Japanese entertainment. Sung by the popular singer Chiyako Sato, the record was released on May 1st 1929 and the film “Tokyo March” was released later that month on May 31st 1929. The record sold 250,000 copies and was a huge success toward getting people interested in the film, which was based on the novel by Kan Kikuchi. Unfortunately, the full 101 minute film is lost. The only version to survive is a condensed version of the story from a 16mm print, running 24:04. Luckily this is not a partial fragment, but it has a beginning, middle, and end to the story, like a digest version of the film. It is impossible to compare the original and shortened version, but it is interesting to compare this story with the other film in this set, “The Water Magician”. Love-at-first-sight and the difference in class for examples. Even if the film is incomplete, the story does have a fully conclusive story which surprisingly still works, and the final emotional pull is both heartbreaking but also uplifting as the truth is revealed. Hopefully one day a full version of the film can be found. But until then, we will have to enjoy the shorter version only. Note: The DVD is region 0 NTSC, playable in any DVD player worldwide.

Video

Digital Meme presents both films in their original non-anamorphic 1.33:1 theatrical ratio, slightly windowboxed with thin black bars on around the image. Both prints were sourced from theatrical film prints stored at the Matsuda Film Productions archive, the largest private film archive preserving silent films in Japan. Both films are preceded by the Matsuda Film Productions logo and text information about Matsuda and their commitment to preserving silent films for postwar audiences. Considering the age of the films and the source, the films look pretty good. Some of the dust and specs have been removed digitally, but there are still a lot of the expected scratches, flickering, and tramlines here and there. Black and white levels look fine and stability is very good. Silent film fans should be quite pleased with the image. The opening scenes in both movies look quite scratchy, but by the second reel the quality starts to pick up.

Audio

There are 2 soundtracks available for “The Water Magician”: Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono (Narration by Shunsui Matsuda) Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono (Narration by Midori Sawato) There is one soundtrack available for “Tokyo March”: Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono (Narration by Midori Sawato) During the silent film era in the west it was common for theaters to have music accompaniment via organ or piano. In Japan it was common to have narrators next to the movie screen to do the voices, narrate the story, and read the intertitles out loud. These people were called “Benshi”. Music accompaniment was also used, making a unique way of viewing movies unusual to the west. People would not only flock to the theater to see their favorite movie stars on screen, but to hear their favorite benshi do the storytelling. The Shunsui Matsuda benshi narration track is a vintage recording, while the Midori Sawato recordings are newly created for the DVDs. Both films have Japanese intertitles with multiple subtitle tracks for the films: Optional English and Japanese subtitles for the narration by Shunsui Matsuda. Optional Chinese, English, Japanese, Korean subtitles for the narration by Midori Sawato. The white colored subtitles caption the narration and the intertitles. Although it is “authentic” to show the film with Japanese benshi narration to recreate the feel of a movie theater in the silent era, there isn’t an option for “silent” or “music only”. Technically, you could just turn off the sound and watch the film, but if subtitles are necessary, there isn’t a subtitle track to translate only the intertitles.

Extras

"Kenji Mizoguchi Revealed: Commentary by film historian Tadao Sato" featurette (14:02) Film critic Tadao Sato talks about the two films in this set, talking about Mizoguchi’s life and the mirroring of his life and art, Mizoguchi’s style, the modernization of Japan at the time, the original stories, the performers, and the importance of silent films. 1.33:1, in Japanese with optional Chinese, English, and Korean subtitles. "A Word From the Benshi - Midori Sawato" featurette (2:28) Narrator Midori Sawato gives a short introduction to Benshi narration and short comments about the two films, including the song for "Tokyo March". 1.33:1, in Japanese with optional English subtitles. The extras are informative, but both feel very short. Less than 3 minutes for Sawato to talk about 2 films is way too short, and since the packaging says "commentary by Tadao Sato", I expected an audio commentary track for the duration of the film, but this is not the case. His comments in the 14 minute featurette have quite a lot of information, but I felt there was a lot more Sato could have elaborated on further.

Packaging

Packaged in a single-disc Amaray keep case, the packaging is bilingual in English and Japanese. Inside is a leaflet with cast & crew listings and biographies on Mizoguchi and the benshi narrators.

Overall

It’s unfortunate that many of Mizoguchi’s silent works are lost. We should be very glad that a few still survive and that Digital Meme has put together 2 sets of Mizoguchi silent films, “Talking Silents 1” and “Talking Silents 2”. (“Talking Silents 2” includes “The Downfall of Osen” and “Tojin Okichi”). Fans of classic Japanese film and fans of silent film should not hesitate to add this to their collection. The DVD can be purchased on Amazon Japan or through Digital Meme’s website directly. This DVD is a 2007 release. Digital Meme has not had any new DVD releases recently, as the company has stated that the difficult DVD market has prevented them from releasing more sets in the home video marketplace. But they have also stated that they have new plans for 2016, which is very exciting news for silent Japanese film fans.

|

|||||

|