|

|

Wolcott: The Complete Series (TV)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th August 2015). |

|

The Show

Wolcott (ATV, 1981) Wolcott (ATV, 1981)

Made by ATV and broadcast in 1981, Wolcott seemed – along with the BBC’s contemporaneous series The Chinese Detective (1981-2) – to represent a newfound awareness of issues of ethnicity and cultural tensions within multicultural Britain. These were themes which previous crime dramas had tended to sweep under the proverbial carpet, or had represented these issues in a, perhaps it’s fair to say, less than enlightened manner. (A bizarre The Sweeney novel focusing on illegal immigration, The Human Pipeline – published in 1977 and written by the pseudonymous ‘Joe Balham’ – attempts to examine some of these issues in a balanced way but evidences the difficulties in applying such an approach within the formulaic structures of crime fiction.) Given that the first black police officer in the UK was for many years erroneously claimed to be Norwell Roberts, who joined the Metropolitan Police in 1966, the previous lack of interest in representing the lives of non-white police officers is perhaps not particularly surprising. (The claim about Roberts being the first black British police officer was erroneous because in 1837, a black policeman served as part of the police force in Carlisle.) It is perhaps even less surprising when one considers that British television crime dramas were, during this period, only beginning to terms with the presence of female police officers, in shows like The Gentle Touch (LWT, 1980-4) and Juliet Bravo (BBC, 1980-5). Wolcott focuses on uniformed police officer Winston Churchill Wolcott (George William Harris), who in the opening sequence of the first episode makes a spectacular bust, arresting two blaggers in the act. Owing to his bravery, Wolcott is given a citation and is promoted to detective constable (later, the case against the robbers is thrown out of court and Wolcott’s actions are questioned). However, Wolcott’s promotion causes friction with his childhood friend Dennis St George (Hugh Quarshie), a university graduate and now the organiser of a local youth club for young black men. Dennis is a firebrand, and sees Wolcott’s acceptance of the citation and promotion as a form of ‘selling out’, telling Wolcott sarcastically that ‘They should give you something for being the white man’s house nigger’.  One evening, an elderly woman is mugged by a young black man, who runs her through (and kills her) with a very specific type of wood chisel. Wolcott finds himself inserted into the investigation into this crime. The youth who committed the crime has ties with local black gangster, and owner of the disreputable Thousand Island nightclub, Reuben Warre (Raul Newney). Reuben has been treading on turf previously occupied by racist white gangster Terry Rowe (Warren Clarke), whose family have ‘owned’ the ‘manor’ for a number of years. Terry’s nose is put out of joint when Reuben begins to form an alliance with Nick, who bankrolls many of Terry’s illegal operations. One evening, an elderly woman is mugged by a young black man, who runs her through (and kills her) with a very specific type of wood chisel. Wolcott finds himself inserted into the investigation into this crime. The youth who committed the crime has ties with local black gangster, and owner of the disreputable Thousand Island nightclub, Reuben Warre (Raul Newney). Reuben has been treading on turf previously occupied by racist white gangster Terry Rowe (Warren Clarke), whose family have ‘owned’ the ‘manor’ for a number of years. Terry’s nose is put out of joint when Reuben begins to form an alliance with Nick, who bankrolls many of Terry’s illegal operations.

Assisted by spiky American journalist Melinda (Christine Lahti), Wolcott’s investigations into this crime lead him into conflict with Dennis, who criticises Wolcott’s pursuit of black suspects for the crime – including local youth Melville Groves (Steven Woodcock), one of the regulars at Dennis’ youth club. Wolcott’s investigation also puts him into conflict with the station’s Community Relations Co-ordinator, Chief Inspector Berry (James Smith), and brings Wolcott into the orbit of corrupt Detective Inspector Charlie Bonham (Chris Ellison). Meanwhile, Wolcott becomes aware of the dominance of heroin amongst the youth of the area – heroin which is being shipped into the country by a Middle Eastern diplomat, Mr Aziz (Darien Angadi) and sold on by Terry. Where most British crime series on television – from Dixon of Dock Green (BBC, to The Sweeney (Euston Films, 1974-8) – had offered depictions of white, usually middle-aged and patriarchal policemen (and, less often, women), during the 1970s some crime-themed television series had become a little more interested in representing multicultural Britain. Particularly notable was David Rose’s series Gangsters (BBC, 1976-8), set within the British Asian community in Birmingham, which was highly self-reflexive in its depiction of ethnicity and cultural tensions within Britain. Laced with postmodern irony, Gangsters initially drew criticism (especially when the Play for Today episode which was the springboard for the series was broadcast in 1975) from those who suggested that the scripts traded in stereotypes: ‘portraying Indians as servile, black men as thugs and white males as culturally unaware’ (Collinson, 2003: np). However, as the series progressed ‘critics slowly began to adjust their perception of the play, accepting that racist characters did not make the programme inherently racist’ (ibid.).  The executive producer of Wolcott, Barry Hanson, had also produced Gangsters. Like Gangsters, Wolcott was criticised for its apparent reliance on stereotypes. In Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television, Stephen Bourne quotes the assertion of actor Elvis Payne (who performed in the series) that ‘It’s [Wolcott is] a terrible, terrible programme […] They say it’s not racist but it is. The black cop is the hero but the series shows lacks in the way the reactionary racist media puts them over—all those ideas about blacks being degenerate and animalistic [….] I’ve talked to a lot of black people on the set about it and we all say we wouldn’t have done it if we’d seen the script. It’s a bad programme and black people shouldn’t stand for it [….] It’s not as if black people have access to the media to produce a counter argument to it. It would be a good thing if it made blacks conscious of how the media ignores them most of the time and when it does deal with them it does so in such a way that is an insult to them’ (Payne, quoted in Bourne, 2005: 202). However, as with Gangsters it could also be argued that the presence of stereotypes within its narrative (driven by the conventions of the crime genre, after all) doesn’t make Wolcott inherently racist: the series has little time for anyone, black or white, other than Wolcott, who is the only truly upstanding character within the series – along with, perhaps, the anti-fascist Socialist Worker speaker in the street market depicted in the first episode, a cameo role played by Alexei Sayle, whose suggestions that the Tory government ‘are trying to set the British people against each other, to split the working class’ lead to him being heckled and threatened by a National Front supporter (Keith Allen). The executive producer of Wolcott, Barry Hanson, had also produced Gangsters. Like Gangsters, Wolcott was criticised for its apparent reliance on stereotypes. In Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television, Stephen Bourne quotes the assertion of actor Elvis Payne (who performed in the series) that ‘It’s [Wolcott is] a terrible, terrible programme […] They say it’s not racist but it is. The black cop is the hero but the series shows lacks in the way the reactionary racist media puts them over—all those ideas about blacks being degenerate and animalistic [….] I’ve talked to a lot of black people on the set about it and we all say we wouldn’t have done it if we’d seen the script. It’s a bad programme and black people shouldn’t stand for it [….] It’s not as if black people have access to the media to produce a counter argument to it. It would be a good thing if it made blacks conscious of how the media ignores them most of the time and when it does deal with them it does so in such a way that is an insult to them’ (Payne, quoted in Bourne, 2005: 202). However, as with Gangsters it could also be argued that the presence of stereotypes within its narrative (driven by the conventions of the crime genre, after all) doesn’t make Wolcott inherently racist: the series has little time for anyone, black or white, other than Wolcott, who is the only truly upstanding character within the series – along with, perhaps, the anti-fascist Socialist Worker speaker in the street market depicted in the first episode, a cameo role played by Alexei Sayle, whose suggestions that the Tory government ‘are trying to set the British people against each other, to split the working class’ lead to him being heckled and threatened by a National Front supporter (Keith Allen).

Gavin Schaffer has argued that Wolcott ‘portrayed a seedy side of multicultural Britain and was criticised by some viewers for presenting black minorities in a negative light’ (Schaffer, 2014: 255). On the series’ broadcast, the Independent Broadcasting Authority received complaints about Wolcott’s use of ‘black youths […] shown as murderers and muggers’ (anonymous complainant, quoted in ibid.). However, the IBA’s response was to suggest that Wolcott offered a ‘realistic’ depiction of inner-city life and ‘paint[ed] good and bad characters from all ethnicities’ – suggesting the ethos of Wolcott was shared with Gangsters, ‘that all ethnicities should be presented as morally equal’ (ibid: 255, 256). One member of the IBA declared that ‘such communities exist, not only in London but in a number of cities in Britain. Should we close our eyes to that fact’ (quoted in ibid.: 255). Lord Thomson, then the chairman of the IBA, offered a defence of the series, claiming that ‘It [Wolcott] was a grim piece. It upset some of our more “liberal” viewers because, in giving a picture of racial tensions in North London it did not pretend that those tensions are a simple matter of whites versus blacks, and it even had a coloured [sic] villain’ (Thomson, quoted in ibid.). Yet another representative of the IBA suggested that Wolcott should be celebrated for getting ‘away from the quite false idea that all the good is on one side or the other’ (quoted in ibid.: 256).  However, the series couldn’t escape the argument that, other than the black actors who appeared in it, the material had ‘no black technical input’ (Karen Ross, quoted in ibid.). As a consequence Wolcott features a protagonist ‘who conforms to white notions of blackness’ and ‘appears synthetic and one-dimensional, a desperate attempt to show that black people are just like whites really’ (Ross, quoted in ibid.). This criticism suggests the show is guilty of the kind of ‘tokenism’ that the Metropolitan Police exploited in their ‘use’ of Norwell Roberts. As if in direct reference to the Met’s use of photo opportunities with Norwell Roberts as a means of promoting ‘positive discrimination’, and the prejudice Roberts experienced from both his colleagues and members of the black community outside the police force (who considered him to be a Judas of sorts), Wolcott confronts many of these issues from the get-go. When Wolcott is promoted to CID, he meets with Chief Superintendent Cosgrove (Paul McDowell), who bluntly dismisses the notion of tokenism and tells Wolcott directly that ‘You are not being brought into the area because you are black. You are here because you have shown over the years that you are an excellent police officer. Of course, any improvement in the, er, community relations will be welcomed by the police. But you are here to prevent crime and catch criminals’. However, the series couldn’t escape the argument that, other than the black actors who appeared in it, the material had ‘no black technical input’ (Karen Ross, quoted in ibid.). As a consequence Wolcott features a protagonist ‘who conforms to white notions of blackness’ and ‘appears synthetic and one-dimensional, a desperate attempt to show that black people are just like whites really’ (Ross, quoted in ibid.). This criticism suggests the show is guilty of the kind of ‘tokenism’ that the Metropolitan Police exploited in their ‘use’ of Norwell Roberts. As if in direct reference to the Met’s use of photo opportunities with Norwell Roberts as a means of promoting ‘positive discrimination’, and the prejudice Roberts experienced from both his colleagues and members of the black community outside the police force (who considered him to be a Judas of sorts), Wolcott confronts many of these issues from the get-go. When Wolcott is promoted to CID, he meets with Chief Superintendent Cosgrove (Paul McDowell), who bluntly dismisses the notion of tokenism and tells Wolcott directly that ‘You are not being brought into the area because you are black. You are here because you have shown over the years that you are an excellent police officer. Of course, any improvement in the, er, community relations will be welcomed by the police. But you are here to prevent crime and catch criminals’.

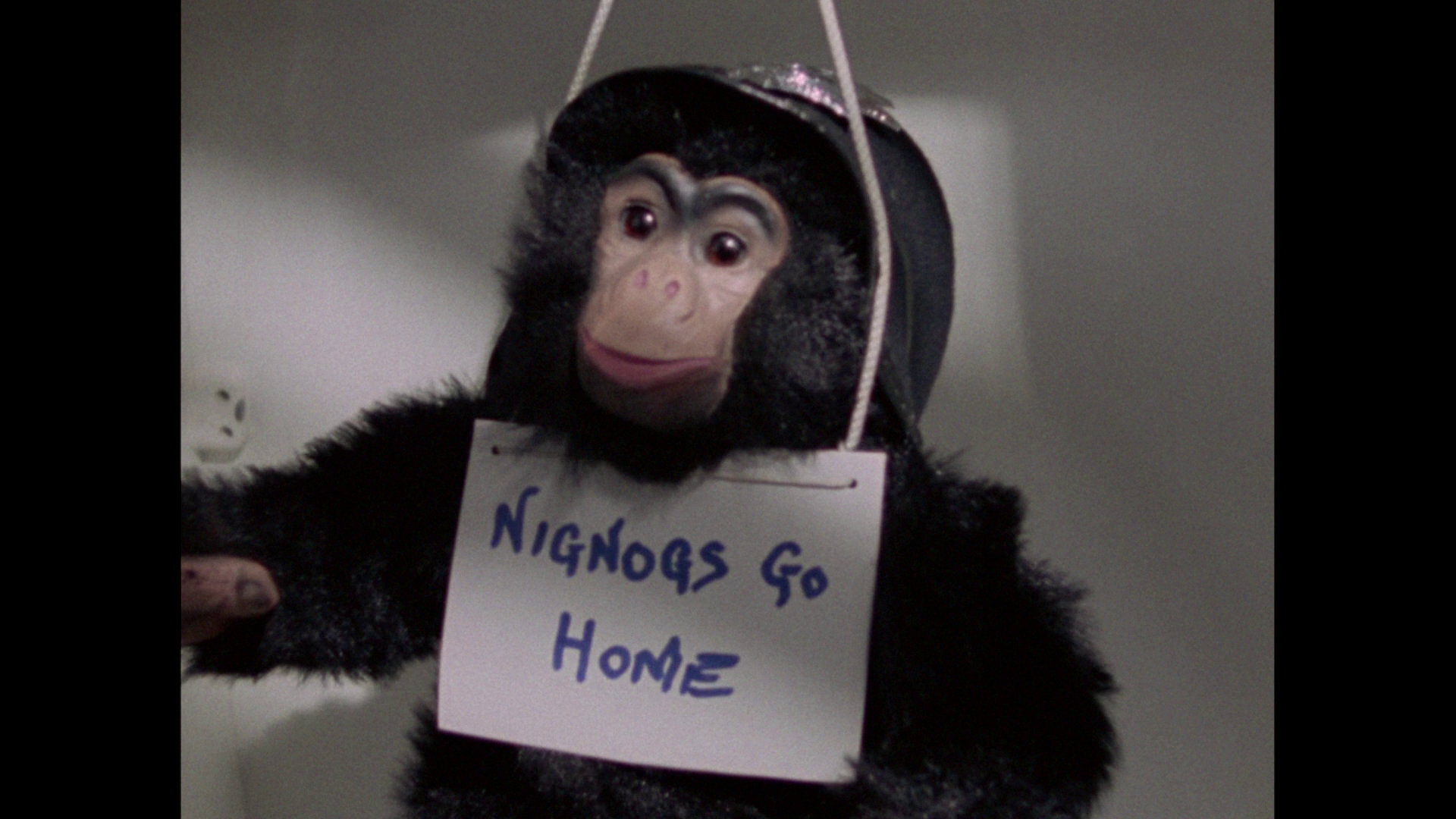

Wolcott himself resists suggestions of tokenism, arguing that he should be defined first and foremost a fighter of crime, rather than as a black police officer. When Melinda, who suggests that she herself has been the victim of a form of prejudice (being hired as a journalist on issues of race by the London newspaper for which she works owing to her origins as a New Yorker – ‘so they think I know all about that, right?’), questions Wolcott about his role as a police officer and asks him if he thinks that it’s ‘like being a Jewish SS officer’, Wolcott reacts angrily. In response, he tells Melinda ‘I’m so tired of this shit [….] Look, I don’t like people who mess over other people. Sometimes I catch them. It’s a simple as that. I mean, er, because I’m black, that shouldn’t keep me out of my natural line of work, should it?’ Wolcott also criticises the academic approach that Berry has towards ‘community relations’. When Wolcott receives two formal complaints after arresting Melville (one from Melville’s drunken stepfather, who claims Wolcott assaulted him; and another from Dennis, who dislikes approach to interviewing Melville), he is called into Berry’s office. Berry questions the way Wolcott handled the investigation, telling Wolcott that he expected him to show ‘a bit of sensitivity to your own community’. This patronising declaration provokes another angry response in Wolcott: ‘My sensitivity towards my community you don’t know a damn thing about, you understand. And you won’t find it in any of those bits of candyfloss on your bookshelf’.  Echoing the experiences of Norwell Roberts, who was faced with bullying and harassment by his fellow officers upon joining the Met whilst also being ostracised by the black community for being a ‘traitor in a white man’s job’, Wolcott finds his new post to be accompanied by cruelty from his colleagues (Roberts, quoted in Verkaik, 1997). He is told by Detective Inspector Gilligan (Martin Dempsey), with whom he later forms a fragile alliance, that ‘You’ve probably noticed that no-one in this building wants to know yer’. ‘Yes’, Wolcott replies before quipping, ‘It’s breaking my heart’. Later, he opens the cupboard in his new office to find a toy monkey, wearing a police helmet, hanging by a length of string and carrying a sign declaring ‘NIGNOGS GO HOME’. Later, Melville tells Wolcott, without a trace of irony, ‘Why don’t you go back to where you came from and leave English people alone?’ Echoing the experiences of Norwell Roberts, who was faced with bullying and harassment by his fellow officers upon joining the Met whilst also being ostracised by the black community for being a ‘traitor in a white man’s job’, Wolcott finds his new post to be accompanied by cruelty from his colleagues (Roberts, quoted in Verkaik, 1997). He is told by Detective Inspector Gilligan (Martin Dempsey), with whom he later forms a fragile alliance, that ‘You’ve probably noticed that no-one in this building wants to know yer’. ‘Yes’, Wolcott replies before quipping, ‘It’s breaking my heart’. Later, he opens the cupboard in his new office to find a toy monkey, wearing a police helmet, hanging by a length of string and carrying a sign declaring ‘NIGNOGS GO HOME’. Later, Melville tells Wolcott, without a trace of irony, ‘Why don’t you go back to where you came from and leave English people alone?’

For his part, Wolcott’s friend Dennis finds himself torn between his militant ideals and his desire to help Wolcott find the murderer of the elderly woman. Dennis, whose distrust of the police takes on Eldridge Cleaver-like dimensions, criticises Wolcott for accepting the promotion to CID. However, Dennis has a strong moral compass; the influx of heroin, and its easy adoption by the young black men who attend his youth club, troubles Dennis. He tells Wolcott that he is unable to be seen to be helping Wolcott for fear of alienating the young men who attend his club, who Dennis says will, as an alternative, simply end up attending the Thousand Island nightclub where drugs and prostitution are an accepted way of life. ‘What are you doing for these kids, Dennis?’, Wolcott asks his friend, ‘You’re letting them get away with all kinds of shit’. ‘Whatever I’m doing, I can’t do if everyone thinks I’m your private play-back machine’, Dennis tells Wolcott. Dennis also has an alliance of sorts with Reuben but seems critical of Reuben’s association with criminal enterprise: at one point, Dennis tells Reuben, ‘Sometimes I wonder whether you want to be Malcolm X or Fagin’. To this, Reuben responds by suggesting Dennis is an idealist, out of touch with reality: ‘You look after youth club’, Reuben says, ‘I’ll handle the real world’. The series’ use of language is interesting, with Wolcott himself demonstrating an ability to codeswitch that enables him to connect with the young black men who are Dennis’ charges: Wolcott speaks received pronunciation when communicating with his colleagues but, when interviewing Melville, for example, Wolcott adopts a strong Jamaican accent. When Wolcott first enters the station to which he has been assigned as a member of the CID team, the uniformed policemen on the desk initially treat him as a suspect – until Wolcott reveals his true identity. Walking through the station, he encounters a black man – a drunk – being escorted out of the cells by a white police officer. ‘Hey, what they want you for, huh?’, the black man asks Wolcott. ‘Dem no want me for nothin’, bruv’, Wolcott responds. This draws the attention of the white police officer, who asks Wolcott sternly, ‘Can I help you?’ ‘I don’t think so’, Wolcott informs him, having already codeswitched back into received pronunciation.   The episode running times are as follows: Episode One (50:21) Episode Two (50:04) Episode Three (51:43) Episode Four (44:49)

Video

The 1080i (25fps) presentation is in the series’ original broadcast ratio of 1.33:1. Using the AVC codec, each episode takes up around 9Gb of space on the disc. The 1080i (25fps) presentation is in the series’ original broadcast ratio of 1.33:1. Using the AVC codec, each episode takes up around 9Gb of space on the disc.

Shot on 35mm, the series has a remarkably polished look, largely thanks to the work of Wolcott’s director of photography, who was none other than the remarkable Roger Deakins. The series begins with fairly naturalistic photography but quickly begins to adopt a film noir¬-esque aesthetic, with strong use of chiaroscuro lighting in offices, etc, and characters appearing out of, and disappearing into, shadow like Harry Lime in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949). There’s also an interesting Peckinpah-esque use of slow-motion from time to time, to mark events that are traumatic for the characters within the narrative. (There’s one big, easily forgivable, gaff in the photography: the reflection of the cameraman – and camera – clearly visible on the side door of a van as it drives off in close-up.) The presentation of Wolcott on this Blu-ray release is excellent, demonstrating a strong level of detail throughout the series. Contrast levels are pleasing, leading to a nicely-balanced image – which works to the series’ benefit, considering the abundance of sequences set in low-light (eg, on the streets at night) and the aforementioned use of chiaroscuro lighting. Some light noise reduction seems to have been applied, but nothing too drastic. The series retains the natural grain structure of 35mm film. The original break bumpers are intact and present in each episode. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This has good range, and though the series is dialogue-based, the track comes alive when music appears on screen (eg, the calypso rhythm in the music over the opening titles, or the performance by Aswad in the Thousand Island club in episode two). Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes a image gallery (1:23).

Overall

>Whilst there’s some validity in some of the criticisms that have been leveled against Wolcott over the years (chiefly that the series trades on stereotypes), dramatically it’s a very strong, gritty series. The only aspect of the show that feels deeply out of place is the presence of Christine Lahti as the American reporter – which feels like a sop to attempts to sell the show overseas. Racist tirades come thick and fast – Terry is particularly guilty of this, using the epithets ‘coon’ and ‘sambo’ with alarming frequency – but, given the nature of the material and its setting in time and place, grow organically out of the narrative. >Whilst there’s some validity in some of the criticisms that have been leveled against Wolcott over the years (chiefly that the series trades on stereotypes), dramatically it’s a very strong, gritty series. The only aspect of the show that feels deeply out of place is the presence of Christine Lahti as the American reporter – which feels like a sop to attempts to sell the show overseas. Racist tirades come thick and fast – Terry is particularly guilty of this, using the epithets ‘coon’ and ‘sambo’ with alarming frequency – but, given the nature of the material and its setting in time and place, grow organically out of the narrative.

Wolcott is set against a climate of dissent. As the mayor notes in the ceremony in which Wolcott receives his citation, ‘It is the temper of the times to question authority’. The police struggle to maintain positive relationships with the community, and even struggle to maintain good relationships amongst themselves. Amongst this disarray, the strong sense of morality represented by Wolcott and Dennis – who are united by similar aims but set against one another because of their methods – emerges as the only truly heroic set of values within the series. Wolcott has some wonderful dialogue: engaged in an altercation in the station’s shower room with the racist PC Fell (played by yet another comedy actor in a cameo role – Rik Mayall), Wolcott tells Fell ‘What I care about what you think is point nought nought one per cent of fuck all, understand?’ On top of this, the photography within the series is truly superb: each episode is shot through with a film noir-esque approach to lighting, staging and photography. The presentation of the series on this Blu-ray release is very impressive, though sadly lacking in contextual material. It’s a deeply pleasing release, coming hot on the heels of Network’s recent and equally impressive Blu-ray release of Quatermass (1979). Both are pretty much essential purchases for fans of British television of that era. References: Bourne, Stephen, 2005: Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television. London: Continuum Collinson, Gavin, 2003: ‘Gangsters (1976-78)’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/534642/ Schaffer, Gavin, 2014: The Vision of a Nation: Making Multiculturalism on British Television, 1960-80. London: Palgrave Macmillan Verkaik, Robert, 1997: ‘DS Roberts calls it a day’. The Independent (25 March, 1997)

|

|||||

|