|

|

The Film

Nightmare City (Umberto Lenzi, 1980) Nightmare City (Umberto Lenzi, 1980)

Beginning his directing career with the 1958 comedy Mia Italida stin Ellada (An Italian in Greece), prolific filmmaker Umberto Lenzi worked in pretty much all of the major filoni (veins/streams) within Italian cinema between the 1960s and 1980s. Lenzi’s work encompasses films within the pepla/sword-and-sandal boom of the early 1960s (Zorro contro Maciste/Samson and the Slave Queen, 1963); adaptations of fumetti (adult comic books, such as Kriminal, 1966) and the James Bond-style ‘Euro-spy’ pictures (008: operazione Steminio/008: Operation Exterminate, 1965; Super 7 chiama Cairo, 1965) of the mid-1960s; thrilling all’italiana/Italian-style thriller (Orgasmo, 1968; Il coltello di ghiaccio/Knife of Ice, 1972) and western all’italiana/Spaghetti Western (Una pistola per cento bare/Pistol for a Hundred Coffins, 1968) pictures of the mid/late-1960s and 1970s; the poliziesco all’italiana/Italian-style police films of the 1970s (Milano odia/Almost Human, 1974; Roma a mano armata/Tough Ones, 1976); the trend for cannibal films (for which Lenzi’s Il paese del sesso salvaggio/The Man from Deep River, 1972, is often credited as initiating); and sword-and-sorcery (Ironmaster, 1983) and haunted house (La casa 3/Ghosthouse, 1988) movies of the 1980s.  In the midst of Lenzi’s work in this broad range of genres – genres that unarguably highlight the anxieties of Italy during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s whilst also occasionally aping Hollywood formulae – perhaps surprisingly, given the popularity of zombie films after the release of Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (Zombie Flesh Eaters, 1979), Lenzi only made two zombie pictures: the film under immediate discussion, Incubo sulla città contaminata (Nightmare City, 1980), and Demoni 3 (Black Demons, 1991). However, neither of these pictures is a zombie film at all – at least, not by the paradigms established in the zombie pictures of George A Romero or, closer to home, Fulci. In contrast with the bulk of Italian zombie films which mimicked the success of Fulci’s Zombi 2, Black Demons returns the zombie to its Vodoun roots, its zombies arguably having more in common with White Zombie (Victor Halperin, 1932) than Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) or its imitators. Likewise, Nightmare City, as Lenzi is fond of reminding his audience in interviews, isn’t really a zombie film: its ‘zombies’ are actually human subjects who have suffered exposure to extreme radiation following an accident at the state nuclear power plant. (Similarly, Lamberto Bava’s Demoni/Demons, 1985, is sometimes cited as a ‘zombie’ film but really it’s a demonic intercession picture, featuring human victims who are ‘possessed’ by a demonic entity. However, for the sake of clarity and ease of reference, throughout this review I’ll refer to the creatures within Nightmare City as ‘zombies’.) This radiation gives the afflicted humans superhuman strength (along with Demons, Nightmare City is usually credited as the first to feature running ‘zombies’ rather than the shambling corpses of earlier zombie pictures) but also depletes their red blood cells rapidly – leading to the creatures evidencing a vampiric tendency to attack the jugulars of their victims and drink their blood. The infected are also invincible, other than by destroying their brains (‘Aim to the brain’ is the advice given by the film’s General Murchison – which is rather like the ‘shoot ‘em in the head’ advice that the sheriff gives via a television interview in Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, which Lenzi asserts he has never viewed). In its action-packed approach to this material, Lenzi’s Nightmare City has much in common with more recent zombie films of the new millennium: the parallels with Danny Boyle’s later 28 Days Later (2001), for example, in which humans are turned into marauding zombie-type creatures after being infected with the Rage Virus, are clear. In the midst of Lenzi’s work in this broad range of genres – genres that unarguably highlight the anxieties of Italy during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s whilst also occasionally aping Hollywood formulae – perhaps surprisingly, given the popularity of zombie films after the release of Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 (Zombie Flesh Eaters, 1979), Lenzi only made two zombie pictures: the film under immediate discussion, Incubo sulla città contaminata (Nightmare City, 1980), and Demoni 3 (Black Demons, 1991). However, neither of these pictures is a zombie film at all – at least, not by the paradigms established in the zombie pictures of George A Romero or, closer to home, Fulci. In contrast with the bulk of Italian zombie films which mimicked the success of Fulci’s Zombi 2, Black Demons returns the zombie to its Vodoun roots, its zombies arguably having more in common with White Zombie (Victor Halperin, 1932) than Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) or its imitators. Likewise, Nightmare City, as Lenzi is fond of reminding his audience in interviews, isn’t really a zombie film: its ‘zombies’ are actually human subjects who have suffered exposure to extreme radiation following an accident at the state nuclear power plant. (Similarly, Lamberto Bava’s Demoni/Demons, 1985, is sometimes cited as a ‘zombie’ film but really it’s a demonic intercession picture, featuring human victims who are ‘possessed’ by a demonic entity. However, for the sake of clarity and ease of reference, throughout this review I’ll refer to the creatures within Nightmare City as ‘zombies’.) This radiation gives the afflicted humans superhuman strength (along with Demons, Nightmare City is usually credited as the first to feature running ‘zombies’ rather than the shambling corpses of earlier zombie pictures) but also depletes their red blood cells rapidly – leading to the creatures evidencing a vampiric tendency to attack the jugulars of their victims and drink their blood. The infected are also invincible, other than by destroying their brains (‘Aim to the brain’ is the advice given by the film’s General Murchison – which is rather like the ‘shoot ‘em in the head’ advice that the sheriff gives via a television interview in Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, which Lenzi asserts he has never viewed). In its action-packed approach to this material, Lenzi’s Nightmare City has much in common with more recent zombie films of the new millennium: the parallels with Danny Boyle’s later 28 Days Later (2001), for example, in which humans are turned into marauding zombie-type creatures after being infected with the Rage Virus, are clear.

In interviews Lenzi’s discussion of his own work frequently asserts his status as a skilled metteur en scène rather than an auteur with a ‘message’ – though there often seems to be a clear worldview running throughout his films. Lenzi’s dismissal of any ‘seriousness’ within his approach to filmmaking tends to be taken at face value, and his pictures are often dismissed as simply exploiting existing trends. This is arguably a reductive approach to Lenzi’s filmography – but that’s the potential subject of an extended thesis. However, it’s fair to say that although he is avowedly not a political filmmaker, Lenzi used Nightmare City to criticise the reliance on nuclear power, once claiming in an interview that ‘If you ask me what is the biggest threat to society, it is contamination from radiation and chemicals that cause sickness and death. It’s not that I wanted a political message, I didn’t, but I did want to have an alarm go off’ (Lenzi, quoted in Shipka, 2011: 128). Specifically, Nightmare City seems to have been inspired by the incident at Seveso in 1976, in which a toxic chemical release accident led to an astoundingly high level of dioxin pollution, ultimately leading to the development of new European-wide industrial safety regulations (Directive 82/501/EC, known as the ‘Seveso Directive’). In this sense, Nightmare City arguably has as much in common with James Bridges’ disaster picture about nuclear power, The China Syndrome (1979), as with Fulci’s Zombi 2.  Nightmare City begins with a television news broadcast about ‘speculation over the facts behind the Department of Health announcement about a radioactive spill [….] at the state nuclear plant’. Television journalist Dean Miller (Hugo Stiglitz) is ordered by his boss, Mr Desmond (Ugo Bologna), to visit the airport and interview a scientist, Dr Haggenbach. Nightmare City begins with a television news broadcast about ‘speculation over the facts behind the Department of Health announcement about a radioactive spill [….] at the state nuclear plant’. Television journalist Dean Miller (Hugo Stiglitz) is ordered by his boss, Mr Desmond (Ugo Bologna), to visit the airport and interview a scientist, Dr Haggenbach.

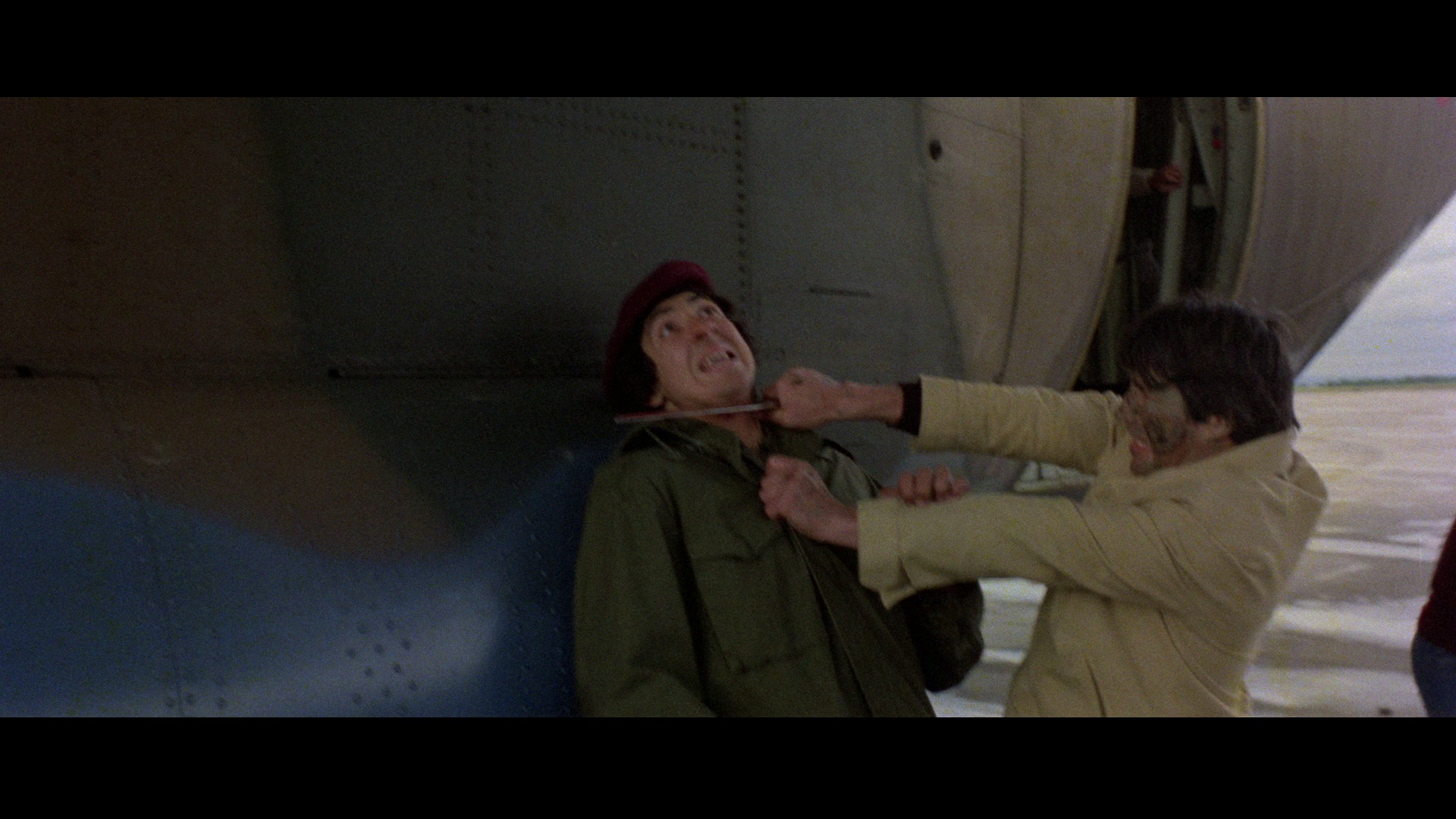

At the airport, a Hercules military transport plane makes an unscheduled landing. Out of the plane spill zombies – apparently normal citizens turned into homicidal maniacs – who attack the police and military forces that have gathered around it. Witnessing this horrific spectacle, Miller makes the decision to flee the scene, returning to the television studios with the intention of interrupting the broadcast of a music programme to warn the city’s population of the attack. However, Miller’s broadcast is cut off, and Miller is called into Mr Desmond’s office, where he is told by Desmond and General Murchison (Mel Ferrer) to remain quiet about what he witnessed at the airport. In response to this, Miller quits his job. In another part of the city, Major Warren Holmes (Francisco Rabal) says goodbye to his wife Sheila (Maria Rosaria Omaggio), a sculptor. Holmes is called to a military base, where he meets with Murchison and a number of other officers. The threat is explained to them in scientific terms: the creatures are humans who have been subjected to extraordinarily high levels of radiation, which have left them with superhuman strength and a profound craving for blood. The government has ordered a cover-up of the whole matter.  Meanwhile, Miller races to the hospital to ‘rescue’ his wife Anna (Laura Trotter), who is a doctor there. He is almost too late: the city’s power supply is cut off following an attack by the zombies on the power plant, and during the blackout the zombies swarm the hospital. However, Miller and Anna manage to escape with their lives. The pair take one of the ambulances, fleeing from the city, as the military try desperately to contain and eradicate the outbreak. Meanwhile, Miller races to the hospital to ‘rescue’ his wife Anna (Laura Trotter), who is a doctor there. He is almost too late: the city’s power supply is cut off following an attack by the zombies on the power plant, and during the blackout the zombies swarm the hospital. However, Miller and Anna manage to escape with their lives. The pair take one of the ambulances, fleeing from the city, as the military try desperately to contain and eradicate the outbreak.

The film’s closing sequence has often been the subject of criticism, with suggestions that is a non-sequitur that appears out of left-field. However, it’s carefully signposted earlier in the film, with the theme of premonition appearing in a number of sequences. When we first see Major Warren and Sheila, they are discussing one of Sheila’s sculptures. She asks Warren if he likes it. Warren tells her that the sculpture gives him a feeling of death, of impending doom, and Sheila touches on the theme of premonition, suggesting that whilst crafting it she had a premonition of something terrible. Shortly after, Anna is introduced working in the city’s hospital. She is tending to a young male patient, Jim, who tells Anna of a dreadful premonition he had during his previous night’s sleep: ‘Last night I had a nightmare’, he says, ‘It looked like war. There was this big explosion [….] And blood, lots of blood’. Anna tries to allay Jim’s anxiety towards the future by telling him, ‘Jim, you don’t have to think about war and death. You have to think about life, okay’. However, not long after, when the zombies begin to attack the hospital, Anna finds Jim’s blood-drained corpse – along with a number of other patients in the same ward. Within this context, Nightmare City’s oft-criticised ending has a clear, albeit underdeveloped, connection with the theme of premonition – and its connection with moments of trauma – established earlier in the picture, with the sense that humanity is doomed to relive these traumatic events (for example, the Seveso incident) until these ‘warnings from the future’ are acted upon and action is taken to prevent them.  Perhaps surprisingly, given that Lenzi is often credited with creating the Italian cannibal film with The Man from Deep River and directed one of the most notorious films within that particular filone (Cannibal Ferox, 1981), the zombies within Nightmare City don’t display the cannibalistic behaviour of the zombies in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) or Fulci’s Zombi 2. Instead, Lenzi’s zombies drink the blood of their victims – to replace their own rapidly depleting red blood cells, we are led to believe. The zombies in this film move quickly and, unlike the zombies in many other entries into the subgenre, attack their prey using weapons – including guns. When the first zombies arrive at the airport via the Hercules military transport plane which makes an unscheduled landing, as they disembark they move slowly – leading the viewer to perceive them as the more conventional shambling monsters. Then, all of a sudden, the creatures spill out of the plane – as Stelvo Cipriani’s pounding score swells on the soundtrack. The violence is swift and brutal, and has more in common with the violence of the urban nightmares depicted within Lenzi’s poliziesco pictures as with the type of violence we normally see within horror films: the zombies attack their victims (the police and military forces gathered around the plane) with whatever is at hand, slitting the throats of soldiers and drinking their blood – and even picking up the weapons of fallen soldiers and using them against their owners. Perhaps surprisingly, given that Lenzi is often credited with creating the Italian cannibal film with The Man from Deep River and directed one of the most notorious films within that particular filone (Cannibal Ferox, 1981), the zombies within Nightmare City don’t display the cannibalistic behaviour of the zombies in Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) or Fulci’s Zombi 2. Instead, Lenzi’s zombies drink the blood of their victims – to replace their own rapidly depleting red blood cells, we are led to believe. The zombies in this film move quickly and, unlike the zombies in many other entries into the subgenre, attack their prey using weapons – including guns. When the first zombies arrive at the airport via the Hercules military transport plane which makes an unscheduled landing, as they disembark they move slowly – leading the viewer to perceive them as the more conventional shambling monsters. Then, all of a sudden, the creatures spill out of the plane – as Stelvo Cipriani’s pounding score swells on the soundtrack. The violence is swift and brutal, and has more in common with the violence of the urban nightmares depicted within Lenzi’s poliziesco pictures as with the type of violence we normally see within horror films: the zombies attack their victims (the police and military forces gathered around the plane) with whatever is at hand, slitting the throats of soldiers and drinking their blood – and even picking up the weapons of fallen soldiers and using them against their owners.

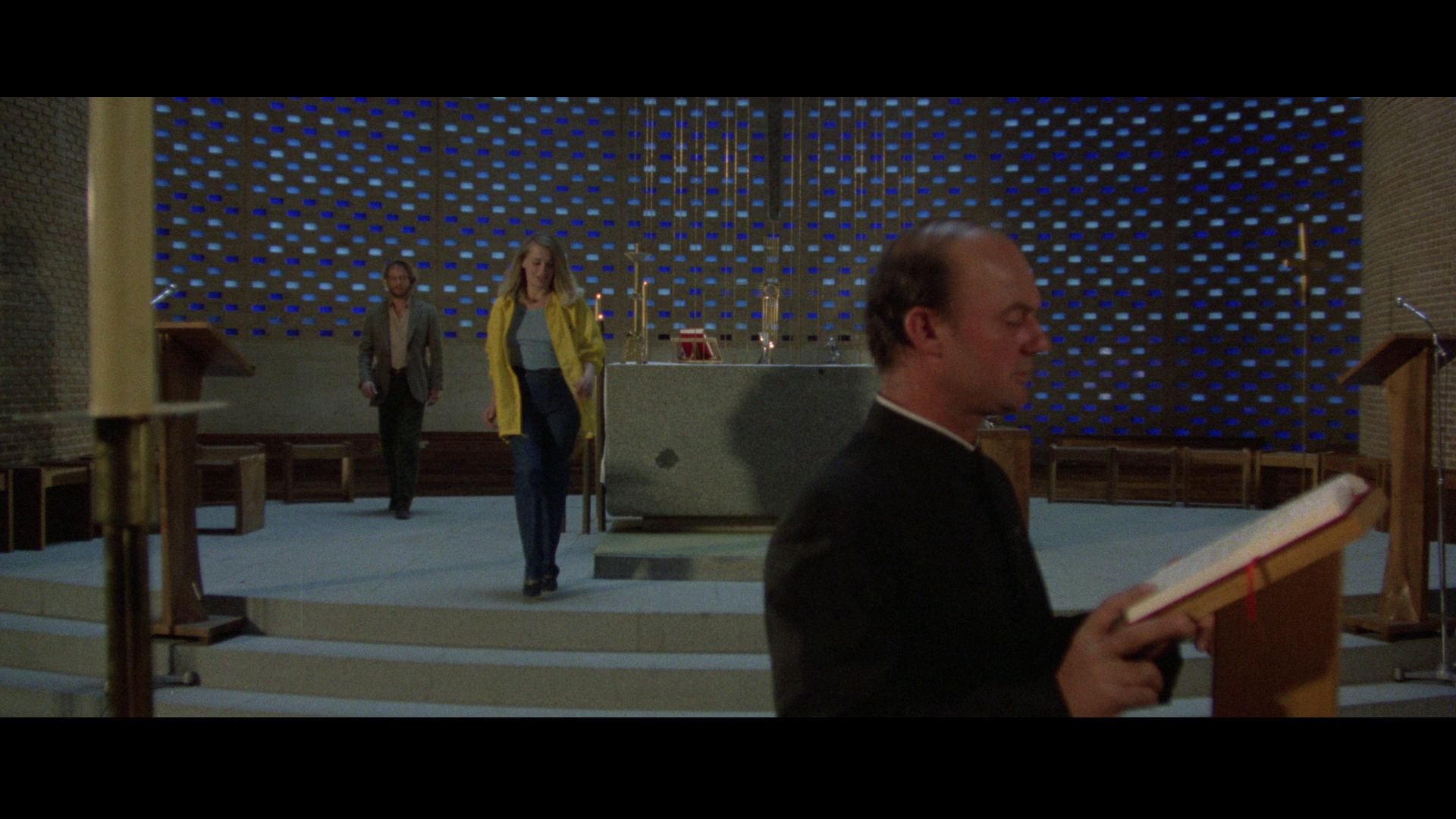

Aside from some heavy makeup on some of the zombies who are in a more advanced stage of decay and therefore in more dire need of sustenance through the ingestion of blood, the film erodes the distinction between human and zombie/infected: for the most part, the zombies appear as humans and, being able to wield weapons, even behave as such. They demonstrate a system of organisation and planning: for example, using subterfuge in an attempt to bypass a military checkpoint outside the city’s power station, before destroying the power supply – thus softening other targets within the city itself. Lenzi’s refusal in interviews to label the creatures as ‘zombies’ evidences this desire to stress the extent to which the humans and the creatures are part of the same species: commenting on an autopsy conducted on one of the first zombies, Murchison declares that the findings ‘categorically rule […] out an extra-terrestrial being. His molecular structure includes him in the human race. A paradox, when you consider what they’ve been doing’. The military within the film struggle to contain the explosion of violence owing to its disorganised and spontaneous nature. Shorn of this easy ability to distinguish between ‘human’ and ‘inhuman’, the rapidly escalating violence in Nightmare City is the urban mayhem of the era of terrorism, the anni di piombi (‘years of lead’) between the bombing of the Piazza Fontana in 1969 and the devastating bombing of the Central Station of Bologna in 1980 – during which the carabinieri were set in running battles against members of militant groups such as the Brigati Rossi/Red Brigades.  Infusing the narrative with depictions of urban violence and zombie attacks which feel more like acts of terrorism – expressing similarities the violence of the poliziesco films of the 1970s that Lenzi directed so well (such as Napoli violenta/Violent Naples, 1976, and Il cinico, l’infame, il violento/The Cynic, the Rat and the Fist, 1977) – Nightmare City emphasises its mundane urban setting over the exotic and Gothic locales used in many of the other zombies films of the era. In the film, attacks by the zombies take place in and against an airport, a television station, a power station, a hospital, a petrol station/roadside diner, a church, a number of large suburban houses, and a fairground. As the film progresses, the zombies are depicted in different stages of decay, with the growth in the number of infected being shown to us via a sequence in which Major Warren takes to the skies in a helicopter and he – and the audience, sharing his perspective – see a large number of zombies spreading across the fields on the outskirts of the city. The outbreak of zombies, set mostly during the day and in recognisable urban locales, to some extent recalls the infected in David Cronenberg’s Rabid (1977) and George A Romero’s The Crazies (1973), although Lenzi’s film stops short of the suggestion in Cronenberg and Romero’s films that the infected are ultimately the ‘victims’ of the military forces sent to stop them. Infusing the narrative with depictions of urban violence and zombie attacks which feel more like acts of terrorism – expressing similarities the violence of the poliziesco films of the 1970s that Lenzi directed so well (such as Napoli violenta/Violent Naples, 1976, and Il cinico, l’infame, il violento/The Cynic, the Rat and the Fist, 1977) – Nightmare City emphasises its mundane urban setting over the exotic and Gothic locales used in many of the other zombies films of the era. In the film, attacks by the zombies take place in and against an airport, a television station, a power station, a hospital, a petrol station/roadside diner, a church, a number of large suburban houses, and a fairground. As the film progresses, the zombies are depicted in different stages of decay, with the growth in the number of infected being shown to us via a sequence in which Major Warren takes to the skies in a helicopter and he – and the audience, sharing his perspective – see a large number of zombies spreading across the fields on the outskirts of the city. The outbreak of zombies, set mostly during the day and in recognisable urban locales, to some extent recalls the infected in David Cronenberg’s Rabid (1977) and George A Romero’s The Crazies (1973), although Lenzi’s film stops short of the suggestion in Cronenberg and Romero’s films that the infected are ultimately the ‘victims’ of the military forces sent to stop them.

Nevertheless, like Cronenberg’s Rabid and Romero’s The Crazies, Nightmare City offers a cynical depiction of authority. From early in the film, Miller is set against his employer, Mr Desmond. Upon being given the job of greeting and interviewing Dr Haggenbach at the airport, Miller realises that he is being asked to ‘spin’ the leak at the nuclear power plant. He questions his orders, telling Mr Desmond that as a journalist, he should maintain objectivity always and not be used as an engine of the state. ‘Forget the philosophy, Miller’, Desmond tells him, ‘Just do what you’re told’. ‘I’m not used to manipulating news, according to my professional ethics’, Miller responds.  After the outbreak has been identified, the media and the military collude in order to cover up the event, keeping it from the public. Following the attack at the airport, Miller returns to the television station where a bizarre dance show (referenced in the dialogue as ‘It’s All Music’) is being broadcast live. (The staging of this show looks for all the world like the oddball Tittupy Bumpity programme in Nigel Kneale’s final Quatermass serial, 1979.) The juxtaposition of this facile television programme and the terror that is unfolding outside brings to mind T S Eliot’s 1925 poem ‘The Hollow Men’ (‘This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but with a whimper’). These two worlds collide soon enough, when in a later sequence the zombies invade the television studio and slaughter the cast and crew. Miller plans to broadcast an emergency message warning the city’s population of the violence that is spreading outwards from the airport. However, he’s frustrated in doing this by Mr Desmond, who has Miller’s broadcast interrupted and calls Miller to his office – where Miller is also confronted by General Murchison. Murchison tells Miller, ‘It’s possible you weren’t aware of the trouble your broadcast could have caused, or the uproar that would have followed it’. ‘I’m a journalist’, Miller tells Murchison matter-of-factly, ‘and my job is to keep the public informed’. However, Murchison commands Miller that ‘nothing is to leak out’ about the events Miller has witnessed. ‘I don’t give a damn about the Defence Department’, Miller declares angrily, ‘In a democratic country nobody can interfere with the freedom of the press for any reason whatsoever’. Desmond is about to tell Miller that he is suspended, but Miller asserts ‘I quit!’ After the outbreak has been identified, the media and the military collude in order to cover up the event, keeping it from the public. Following the attack at the airport, Miller returns to the television station where a bizarre dance show (referenced in the dialogue as ‘It’s All Music’) is being broadcast live. (The staging of this show looks for all the world like the oddball Tittupy Bumpity programme in Nigel Kneale’s final Quatermass serial, 1979.) The juxtaposition of this facile television programme and the terror that is unfolding outside brings to mind T S Eliot’s 1925 poem ‘The Hollow Men’ (‘This is the way the world ends / Not with a bang but with a whimper’). These two worlds collide soon enough, when in a later sequence the zombies invade the television studio and slaughter the cast and crew. Miller plans to broadcast an emergency message warning the city’s population of the violence that is spreading outwards from the airport. However, he’s frustrated in doing this by Mr Desmond, who has Miller’s broadcast interrupted and calls Miller to his office – where Miller is also confronted by General Murchison. Murchison tells Miller, ‘It’s possible you weren’t aware of the trouble your broadcast could have caused, or the uproar that would have followed it’. ‘I’m a journalist’, Miller tells Murchison matter-of-factly, ‘and my job is to keep the public informed’. However, Murchison commands Miller that ‘nothing is to leak out’ about the events Miller has witnessed. ‘I don’t give a damn about the Defence Department’, Miller declares angrily, ‘In a democratic country nobody can interfere with the freedom of the press for any reason whatsoever’. Desmond is about to tell Miller that he is suspended, but Miller asserts ‘I quit!’

Miller’s comment about the freedom of the press feels a little didactic, as if it is a moment of intrusion for the authorial voice. Similar moments occur later in the film; many of these lines of dialogue are given to Anna. For example, after Miller and Anna have escaped from the hospital, they take an ambulance and flee from the city. ‘How can a thing like this happen?’, Miller asks. ‘It’s part of the vital cycle of the human race’, Anna declares cynically, ‘create and obliterate, until we destroy ourselves’. ‘Words! We’re up against a race of monsters’, Miller protests dramatically. ‘Yes, created by other monsters who only have one thing on their mind: the discovery of greater power’, Anna informs him, ‘At least this time there won’t be any historical justifications, even if any of us survive’. ‘Do you think it’s possible to stop them?’, Miller asks. ‘The infection is like an oil stain’, Anna suggests, ‘and who knows how far the contagion has spread now?’  Later, in yet another moment that feels like the intrusion of the author’s voice, Miller and his wife find a temporary refuge in an abandoned roadside diner. Miller takes the opportunity to make him and Anna a cup of instant coffee – a product which Anna describes sarcastically as a wonder of the modern age, ‘like Coca-Cola and nuclear energy. Believe me, we are living in an age of advantages’. ‘Do you think we should give up the advantages we have gained?’, Miller asks. ‘Maybe it would be better’, Anna suggests, ‘However, it’s not the fault of science and technology but of man. We pride ourselves on having invented computers, and we were not able to predict a mess like this [….] We’re partly to blame ourselves. Just think of the lives we’ve led up to today, shut in those ridiculous cities, in steel and concrete jungles, like machines’. ‘All this had to happen to realise the truth’, Miller suggests. ‘Let’s hope it isn’t too late’, Anna tells him. Moments like this, and those above, suggest that though Lenzi has disavowed the notion that Nightmare City (like the majority of his other films) is a ‘political’ film, the picture has a clear worldview that it wishes to get across: that the human desire for power is corruptive, and that we should take heed of the premonitions – or feelings of dread or anxiety – that we connect with such issues as the use of nuclear power. In this context, the theme of premonition (and its reinforcement through the film’s closing sequence) is pivotal. Later, in yet another moment that feels like the intrusion of the author’s voice, Miller and his wife find a temporary refuge in an abandoned roadside diner. Miller takes the opportunity to make him and Anna a cup of instant coffee – a product which Anna describes sarcastically as a wonder of the modern age, ‘like Coca-Cola and nuclear energy. Believe me, we are living in an age of advantages’. ‘Do you think we should give up the advantages we have gained?’, Miller asks. ‘Maybe it would be better’, Anna suggests, ‘However, it’s not the fault of science and technology but of man. We pride ourselves on having invented computers, and we were not able to predict a mess like this [….] We’re partly to blame ourselves. Just think of the lives we’ve led up to today, shut in those ridiculous cities, in steel and concrete jungles, like machines’. ‘All this had to happen to realise the truth’, Miller suggests. ‘Let’s hope it isn’t too late’, Anna tells him. Moments like this, and those above, suggest that though Lenzi has disavowed the notion that Nightmare City (like the majority of his other films) is a ‘political’ film, the picture has a clear worldview that it wishes to get across: that the human desire for power is corruptive, and that we should take heed of the premonitions – or feelings of dread or anxiety – that we connect with such issues as the use of nuclear power. In this context, the theme of premonition (and its reinforcement through the film’s closing sequence) is pivotal.

Nightmare City was riginally released on home video in the UK, prior to the Video Recordings Act, by VTC in 1982. That tape was cut by approximately one minute. A VHS release from Stablecane Video followed in 1986; this release was missing just over three minutes of footage. The film was finally passed uncut for home video release in 2003. Nightmare City is presented here uncut, with a running time of 91:00.

Video

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Nightmare City contains two presentations of the film. Both of these presentations are in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and present the film in its intended 2.35:1 aspect ratio. A) The first presentation, and the one worth buying this disc for, is a new 2k restoration of the negative that has been conducted by Arrow Films themselves. This presentation takes up approximately 26Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.  Shot in Techniscope, the budget-saving 2-perf format introduced in the early 1960s and popular in Italy during the 1960s and 1970s, the photography in Nightmare City evidences the characteristics of a Techniscope production. (Halving the amount of film used, Techniscope saved money during production, though it’s said that by the end of the 1970s the lab costs for films shot in Techniscope were higher than those for films shot in conventional anamorphic widescreen processes.) One of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to use lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Shot in Techniscope, the budget-saving 2-perf format introduced in the early 1960s and popular in Italy during the 1960s and 1970s, the photography in Nightmare City evidences the characteristics of a Techniscope production. (Halving the amount of film used, Techniscope saved money during production, though it’s said that by the end of the 1970s the lab costs for films shot in Techniscope were higher than those for films shot in conventional anamorphic widescreen processes.) One of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to use lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)

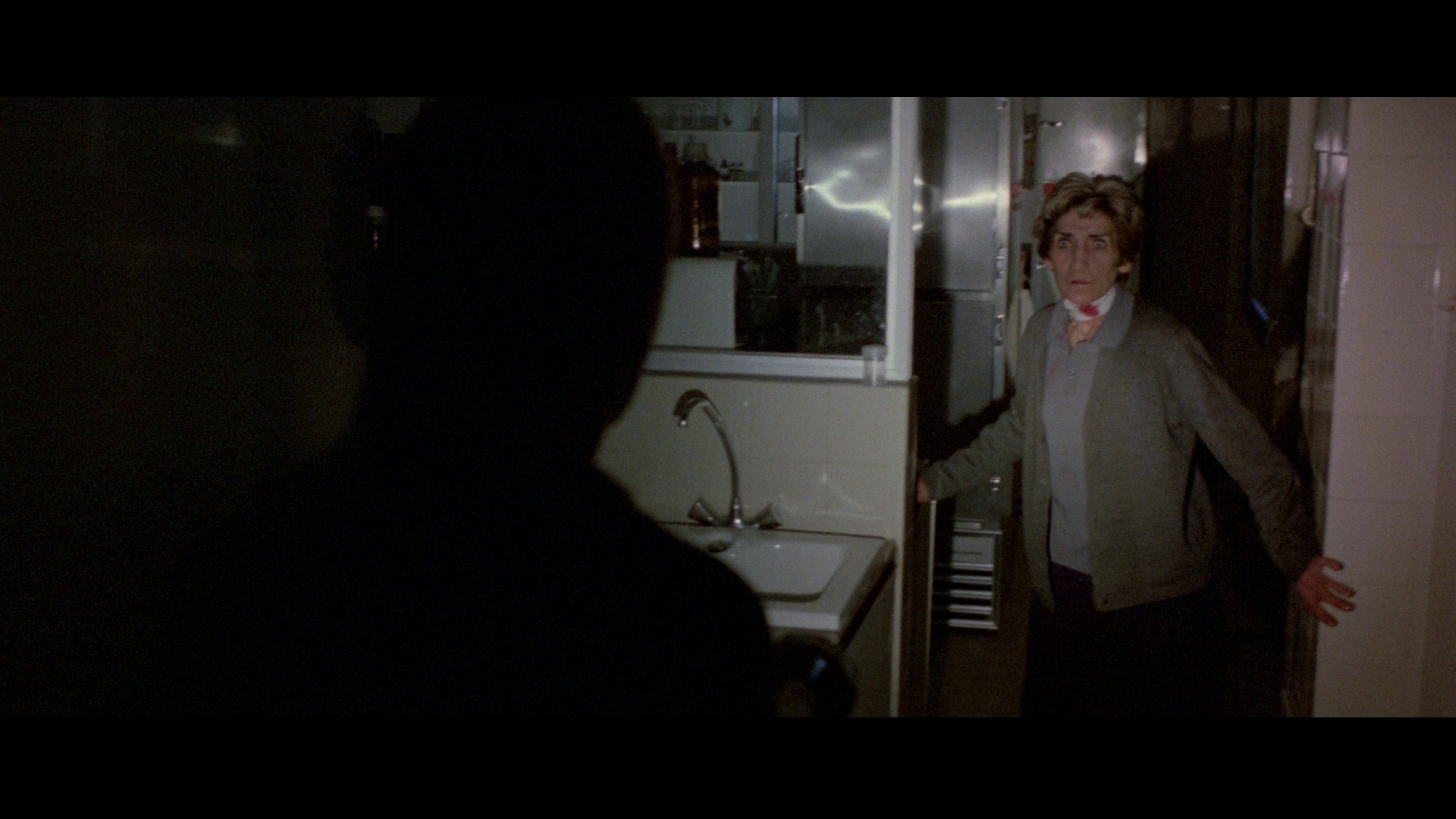

As a film shot in Techniscope, the photography within Nightmare City evidences the depth of field associated with the format – even within low light sequences (for example, in the hospital after the zombies have caused the blackout). This primary presentation of the film has a pleasing sense of depth throughout, communicating this aspect of the Techniscope photography very well, with a strong level of detail present within the image. Contrast is very good too, and is nicely-balanced throughout most of the film. However, damage to the picture can be seen throughout much of Nightmare City, and Arrow’s promotional material suggests that this may have been owing to a careless approach to cleaning the material – with the solvents essentially rotting the emulsion whilst the negative was stored in its canisters. As a consequence, though the image is very good for much of the film’s running time, there are a number of sequences that evidence instability – principally density fluctuations, chemical staining and colour shifting – with a concomitant ‘flicker’ effect that some viewers may find distracting. Attempts have apparently been made to mitigate the damage, but it’s still present. The damage itself is intermittent: it’s particularly noticeable in the first reel, but much less so in some later sequences.  That said, the damage is wholly photochemical and therefore (for my money) entirely acceptable. (As a photographer who still works with film and experiments with it, I find this natural, organic damage has something of a unique appeal, connecting the film to its origins as a film - - and appreciate Arrow’s decision to present it ‘as is’.) This new transfer is in many ways a revelation, evidencing a level of detail – not to mention much improved contrast levels – that is above and beyond any previous home video release of the film. It also contains a richness of colour that isn’t present in the secondary presentation. That said, the damage is wholly photochemical and therefore (for my money) entirely acceptable. (As a photographer who still works with film and experiments with it, I find this natural, organic damage has something of a unique appeal, connecting the film to its origins as a film - - and appreciate Arrow’s decision to present it ‘as is’.) This new transfer is in many ways a revelation, evidencing a level of detail – not to mention much improved contrast levels – that is above and beyond any previous home video release of the film. It also contains a richness of colour that isn’t present in the secondary presentation.

A characteristically excellent encode ensures that this presentation of Nightmare City, despite the damage evident within it, has the appearance of 35mm film – or as near as a digital simulacrum of 35mm film will allow. B) The secondary presentation, taking up approximately 17Gb of space on the disc, is an older scan of a 4-perf dupe negative sourced from Minerva Films, and previously released on Blu-ray in the US by Raro. During the 1960s, when Techniscope films were blown-up using dye transfer processes in use by Technicolor Italia, it was possible to skip the dupe negative step and ‘save’ a generation, thus resulting in an image with a finer grain structure and deeper blacks (characteristics of films produced using dye transfer processes generally, not just those shot in Techniscope). In the 1970s, for economic reasons dye transfer printing for films shot in Techniscope was replaced with the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative (and an additional ‘generation’ for the material). This resulted in weaker contrast and a more coarse grain structure to Techniscope films released in the 1970s and beyond. In line with this, the secondary presentation of Nightmare City on this disc, sourced from such a 4-perf dupe negative, evidences a noticeable softness to the image and much weaker contrast than the primary presentation, and also seems to have undergone some digital noise reduction. It’s much less satisfying than the primary presentation, though obviously doesn’t suffer from the damage that has afflicted the film’s negative. Some viewers may find the stability of this presentation preferable to Arrow’s new transfer – and it’s fair to say that both presentations offer an improvement over the film’s various DVD releases.   NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review, including some comparing the two presentations of the film.

Audio

With both presentations, the viewer has the option of watching the film in English or Italian; both are presented in LPCM 1.0 mono. As, like many Italian productions, Nightmare City was shot with an international cast and post-synched sound, neither track is really more (or less) ‘legitimate’ than the other. That said, some of the dubbing in the English track is a little distracting (eg, the thick ‘New Yoik’ accents of some of the dancers in the television studio), and for that reason the Italian dub arguable offers a richer experience – though in terms of content, there’s really very little difference between the two. Both tracks are in great shape with strong range – but the Italian track sounds a little cleaner and is slightly less ‘muddy’ than the English dub. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included for the English track, and optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue are included for the Italian track. (The latter aren’t available for selection via the disc menu, and are selected automatically when one chooses to watch the film via the Italian track.) These subs are easily readable but contain a few easily forgivable typographical and grammatical errors (‘people cares’, repeated twice at approximately twenty-five minutes into the film; the phrase ‘we proud ourselves’).

Extras

The disc includes a very nice booklet which contains information about the restoration of the film and a new piece by John Martin, the author of Seduction of the Gullible, entitled ‘Fade Away and Radiate: Umberto Lenzi’s Nightmare City’. Martin’s piece situates Nightmare City within the context of the Italian zombie film and reflects on Lenzi’s career as a whole. It’s written in Martin’s usual informal style (and contains a particularly good description of It’s All Music as ‘a disco-dancing wet dream of Berlusconi-esque proportions). The booklet is illustrated with images from the film.  On the disc, the film is accompanied by: On the disc, the film is accompanied by:

- An audio commentary by Chris Alexander. The editor of Fangoria offers a fan’s view of the film. It’s a chatty commentary. Alexander sometimes resorts to simply describing the onscreen action, but on the whole it’s a lively piece. - ‘The Limits of Restoration’ featurette (4:34) is a nicely-edited piece that focuses on the problems faced by Arrow in restoring the film, with onscreen text offering a brief discussion of the Techniscope process and an overview of the issues with the film’s negative balanced by side-by-side comparisons of the two presentations of the film. - A new interview with Umberto Lenzi (28:40) sees Lenzi reflecting on his work on the picture. The anecdotes here are the ones that fans of Lenzi will no doubt have heard before, but as ever Lenzi delivers them with a strong amount of enthusiasm. Lenzi discusses his approach to the script and his attempts to steer it away from the zombie film phenomenon. Lenzi insists again that the creatures in the film aren’t zombies at all – but ‘Quentin [Tarantino] and everyone else keeps thinking they’re zombies. It’s okay with me because the movie has been amazingly successful’. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - A new interview with Maria Rosaria Omaggio (7:41), in which the actress who played Sheila in the film reads from a ‘letter’ she has prepared ‘to the horror movie fans’. She talks about her career and her dislike of horror films generally. She reflects on her work with Mel Ferrer and Francisco Rabal, who Omaggio claims struggled to perform their onscreen kiss owing to the fact that Omaggio was at the time younger than Rabal’s daughter. Omaggio speaks in thickly accented English, but her comments are accompanied by optional English subtitles. - A new interview with Eli Roth (10:33). Roth praises Lenzi’s ‘no bullshit’ approach to filmmaking and the fact that Lenzi’s films are ‘fucking non-stop right to the end’. Using his Umberto Lenzi DVDs as a prop, Roth discusses Lenzi’s work and talks about his enthusiasm for Lenzi’s films – though it’s noticeable that Roth only focuses on Lenzi’s post-1970 films (the cannibal films and the poliziesco pictures). Roth’s enthusiasm for Nightmare City, in particular, feels genuine. - The film’s original trailer (3:45). - Alternate opening titles (2:10). These are simply the English opening titles for the retitling of the film as ‘Attack of the Zombies’.

Packaging

Housed in an Amaray case, the release comes with reversible artwork: new artwork on one side, and the more familiar artwork (with the title City of the Walking Dead) on the other.

Overall

Despite the claims that are often made that Lenzi is a journeyman director, his work is much more interesting than it’s often given credit for being, and this is true of Nightmare City. Stiglitz’s performance as the film’s protagonist is a little flat, and the picture could have benefited from a performance by Franco Nero or Fabio Testi (both of whom Lenzi has suggested he wanted for the part) to anchor it. Nevertheless, Nightmare City offers something substantially different to the majority of Italian zombie films of the era, and it’s a particularly interesting film when its depiction of violence is framed against the poliziesco all’italiana – with its focus on urban violence and terrorism – than the horror films of the period. Certainly, it’s probably fair to say that the film – with its urban, rather than exotic or Gothic setting – has more in common with Lenzi’s poliziesco pictures than with the other Italian zombie films. The horrors of this film take place almost entirely in daylight, the attacks by the zombies coming thick and fast in locations that are iconic of modern life (airports, hospitals, fairgrounds, roadside diners, thoroughly modern homes). It’s also true that there’s a certain element of misogyny within Nightmare City (and that’s a claim that can be levelled against a number of Lenzi’s films) – with the structure of the narrative establishing three men who fight to save their womenfolk (Murchison’s daughter Jessica – played by Zombi 2’s Stefania D’Amario – Holmes’ wife Sheila, and Miller’s wife Anna) and numerous sequences in which women are stripped and murdered brutally by the zombies in scenes that look more like sex crimes than anything else. The violence throughout the film is particularly strong whilst also avoiding the offal-based ‘delights’ of the other Italian zombie films: throats are cut, an eyeball is gouged out with a blade, and zombies are shot in their heads (‘Aim to the brain!’), and surprisingly a child victim of the violence is shown in the fairground at the climax of the picture. Certainly, Nightmare is a more frequently violent film than, say, Zombi 2 – and the mostly starkly realistic urban violence of Lenzi’s picture is arguably more impactful than the excessive setpieces of films such as Andrea Bianchi’s La notti del terrore (Nights of Terror, 1981). Despite the claims that are often made that Lenzi is a journeyman director, his work is much more interesting than it’s often given credit for being, and this is true of Nightmare City. Stiglitz’s performance as the film’s protagonist is a little flat, and the picture could have benefited from a performance by Franco Nero or Fabio Testi (both of whom Lenzi has suggested he wanted for the part) to anchor it. Nevertheless, Nightmare City offers something substantially different to the majority of Italian zombie films of the era, and it’s a particularly interesting film when its depiction of violence is framed against the poliziesco all’italiana – with its focus on urban violence and terrorism – than the horror films of the period. Certainly, it’s probably fair to say that the film – with its urban, rather than exotic or Gothic setting – has more in common with Lenzi’s poliziesco pictures than with the other Italian zombie films. The horrors of this film take place almost entirely in daylight, the attacks by the zombies coming thick and fast in locations that are iconic of modern life (airports, hospitals, fairgrounds, roadside diners, thoroughly modern homes). It’s also true that there’s a certain element of misogyny within Nightmare City (and that’s a claim that can be levelled against a number of Lenzi’s films) – with the structure of the narrative establishing three men who fight to save their womenfolk (Murchison’s daughter Jessica – played by Zombi 2’s Stefania D’Amario – Holmes’ wife Sheila, and Miller’s wife Anna) and numerous sequences in which women are stripped and murdered brutally by the zombies in scenes that look more like sex crimes than anything else. The violence throughout the film is particularly strong whilst also avoiding the offal-based ‘delights’ of the other Italian zombie films: throats are cut, an eyeball is gouged out with a blade, and zombies are shot in their heads (‘Aim to the brain!’), and surprisingly a child victim of the violence is shown in the fairground at the climax of the picture. Certainly, Nightmare is a more frequently violent film than, say, Zombi 2 – and the mostly starkly realistic urban violence of Lenzi’s picture is arguably more impactful than the excessive setpieces of films such as Andrea Bianchi’s La notti del terrore (Nights of Terror, 1981).

In terms of its ecological subtext, Nightmare City belongs alongside Bruno Mattei’s more absurd Virus – L’inferno dei morti viventi (Zombie Creeping Flesh, 1981). Lenzi’s criticism of nuclear power remains strong throughout the picture. The film also demonstrates a distrust of authority, and despite Lenzi’s claim that he’s not a ‘political’ or message-oriented filmmaker, some of the dialogue (for example, that criticising the collusion between the military and the media, and some of Anna’s lines questioning our application of science and our refusal to listen to warnings about it) feels a little didactic.  The Italian language version of the picture arguably works better than the more familiar English dub, owing to the absence of some of the more outrageous ‘New Yoik’ accents that are present in the English language version. The Italian language version of the picture arguably works better than the more familiar English dub, owing to the absence of some of the more outrageous ‘New Yoik’ accents that are present in the English language version.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Nightmare City contains some excellent new contextual material, and the new transfer from the film’s negative is a revelation – though it contains some intermittent damage that some viewers may find easier to adjust to than others. In all other areas, the new presentation is a huge improvement over previous home video presentations of the film: comparing the new transfer with the older presentation sourced from the 4-perf dupe negative evidences the extent to which the new presentation taken from the film’s negative displays a much greater level of detail and better contrast levels. It’s to Arrow’s credit that they’ve included both transfers, allowing the viewer to choose for her/himself. In sum, Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation of Nightmare City is, for the film’s fans, a dream come true. (See what I did there?) References: Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Presentation A: new 2k scan of negative

Presentation B: older scan of 4-perf dupe negative

Additional grabs from new 2k scan of the negative:

|

|||||

|