|

|

Robbery (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th September 2015). |

|

The Film

Robbery (Peter Yates, 1967) Robbery (Peter Yates, 1967)

Loosely based on the Great Train Robbery of 1963, Peter Yates’ Robbery (1967) opens with a gang staging the theft of diamonds. In an elaborately planned robbery, the gang – consisting of Dave (William Marlowe), Frank (Barry Foster) and Jack (Clinton Greyn) – stage a car accident involving the vehicle carrying the diamonds and, posing as ambulance drivers, collect the man to whom the briefcase in which the diamonds are held is attached. They transport him into the ambulance and detach the briefcase from the chain which binds it to his wrist, taking the diamonds from it. The thieves are pursued by the police but manage to lose them following a near-miss involving a class of schoolchildren crossing the road. The heist successful, the members of the gang retreat to their ‘normal’ lives: Dave runs a men’s clothing shop, and Jack owns a garage. They regroup with the mastermind of the operation, Paul Clifton (Stanley Baker), who persuades them to use the takings from the previous robbery in order to bankroll another, more ambitious heist: the theft of an estimated three or four million pounds from the night mail train from Glasgow to London, which Clifton reasons will be loaded with loot on the Tuesday following the Bank Holiday weekend. However, for this bigger heist to succeed, they seek the assistance of other ‘specialists’, including Ben (George Sewell) and Robinson (Frank Finlay). The latter, a prisoner who was previously Clifton’s cellmate, is a former employee of a bank who has insider knowledge that is invaluable to the operation; Clifton has a reluctant Robinson sprung from prison in order to railroad him into co-operating with the heist.  Meanwhile, the schoolteacher (Rachel Herbert) who was accompanying the children who witnessed the getaway following the diamond robbery identifies Jack in a line-up. This puts Clifton’s gang on the radar of Inspector George Langdon (James Booth), who deduces that the gang are planning another heist over the Bank Holiday weekend. In the build-up to the robbery of the night mail train, Langdon puts pressure on Jack and Dave, hoping that they will lead him to the diamonds and reveal the target of their next operation. Meanwhile, the schoolteacher (Rachel Herbert) who was accompanying the children who witnessed the getaway following the diamond robbery identifies Jack in a line-up. This puts Clifton’s gang on the radar of Inspector George Langdon (James Booth), who deduces that the gang are planning another heist over the Bank Holiday weekend. In the build-up to the robbery of the night mail train, Langdon puts pressure on Jack and Dave, hoping that they will lead him to the diamonds and reveal the target of their next operation.

With the date of the new, highly ambitious train robbery rapidly approaching, Paul finds his relationship with his wife Kate (Joanna Pettet) becoming increasingly fractious. He also struggles to win over the reluctant Robinson – who is insistent on contacting his family despite Paul telling him that the police will have them under surveillance – and confirm the assistance of Ben and his hangers-on, who want a much larger slice of the proverbial pie than Paul was willing to offer them. Steve Chibnall has suggested that during the 1960s, with some notable exceptions, British filmmakers had focused on capturing ‘the upbeat mood accompanying “Swinging London”’ and had therefore steered away from the production of serious crime films in favour of ‘lighter subjects with greater international appeal’ (Chibnall, 2008: 235). There was a focus on the ‘spectacular (James Bond) or comedic (Ealing)’: the crime pictures that were produced within Britain during that period tended to favour the conventions of ‘the caper film, a subgenre that seemed to capture the frivolousness and irreverence of the era’ (ibid.). Films such as The Italian Job (Peter Collinson, 1969) and Gambit (Ronald Neame, 1966) proliferated. On the other hand, following the arrest of the Krays in 1968 ‘the spotlight was suddenly illuminating the darker recesses of the criminal underworld’, leading to the production of a number of underworld-set pictures which treated their subject in a somber manner: for example, Performance (Donald Cammell & Nicholas Roeg, 1970), Get Carter (Mike Hodges, 1972) and Villain (Michael Tuchner, 1971).  However, Chibnall argues, Peter Yates’ Robbery (1967) is a notable exception to the trend in British crime films of the mid-1960s to focus on the ‘caper’ and ride on the chipper coattails of the ‘Swinging London’ phenomenon (ibid.). Robbery’s justly celebrated car chase sequence, a precursor to the similar era-defining car chase in Yates’ subsequent Bullitt (1968), makes for an interesting comparison with the spectacular chase involving the Minis in Peter Collinson’s The Italian Job, another heist film which (like Robbery) was delivered by Oakhurst Productions, the production company Stanley Baker established with Michael Deeley. (Interestingly, Deeley has said that though Oakhurst produced The Italian Job, Baker didn’t want anything to do with Collinson’s film as ‘[i]t [The Italian Job] wasn’t his sort of picture’; Deeley, quoted in Field, 2001: np.) Iain Borden has noted that unlike the Mini chase in The Italian Job, the opening car chase in Robbery ‘is shot in an extremely realistic and factual manner’, using ‘normal streets (not tunnels, weirs or arcades)’, with the camera offering the audience a view from the perspective of the drivers, and with ‘little dialogue to detract from what is essentially a neo-reportage piece of cinema, shot without official permission around London’s Ladbroke Grove and including at least one real-life near miss’ (Borden, 2012: 55). The chase in Robbery lacks the ‘expressive theatricalities’ of the similar chase in The Italian Job and is dominated by a ‘sense of frenzy’ which plays out ‘more like a high-speed game of chess against the clock than the playground-like antics of The Italian Job’ (ibid.). However, Chibnall argues, Peter Yates’ Robbery (1967) is a notable exception to the trend in British crime films of the mid-1960s to focus on the ‘caper’ and ride on the chipper coattails of the ‘Swinging London’ phenomenon (ibid.). Robbery’s justly celebrated car chase sequence, a precursor to the similar era-defining car chase in Yates’ subsequent Bullitt (1968), makes for an interesting comparison with the spectacular chase involving the Minis in Peter Collinson’s The Italian Job, another heist film which (like Robbery) was delivered by Oakhurst Productions, the production company Stanley Baker established with Michael Deeley. (Interestingly, Deeley has said that though Oakhurst produced The Italian Job, Baker didn’t want anything to do with Collinson’s film as ‘[i]t [The Italian Job] wasn’t his sort of picture’; Deeley, quoted in Field, 2001: np.) Iain Borden has noted that unlike the Mini chase in The Italian Job, the opening car chase in Robbery ‘is shot in an extremely realistic and factual manner’, using ‘normal streets (not tunnels, weirs or arcades)’, with the camera offering the audience a view from the perspective of the drivers, and with ‘little dialogue to detract from what is essentially a neo-reportage piece of cinema, shot without official permission around London’s Ladbroke Grove and including at least one real-life near miss’ (Borden, 2012: 55). The chase in Robbery lacks the ‘expressive theatricalities’ of the similar chase in The Italian Job and is dominated by a ‘sense of frenzy’ which plays out ‘more like a high-speed game of chess against the clock than the playground-like antics of The Italian Job’ (ibid.).

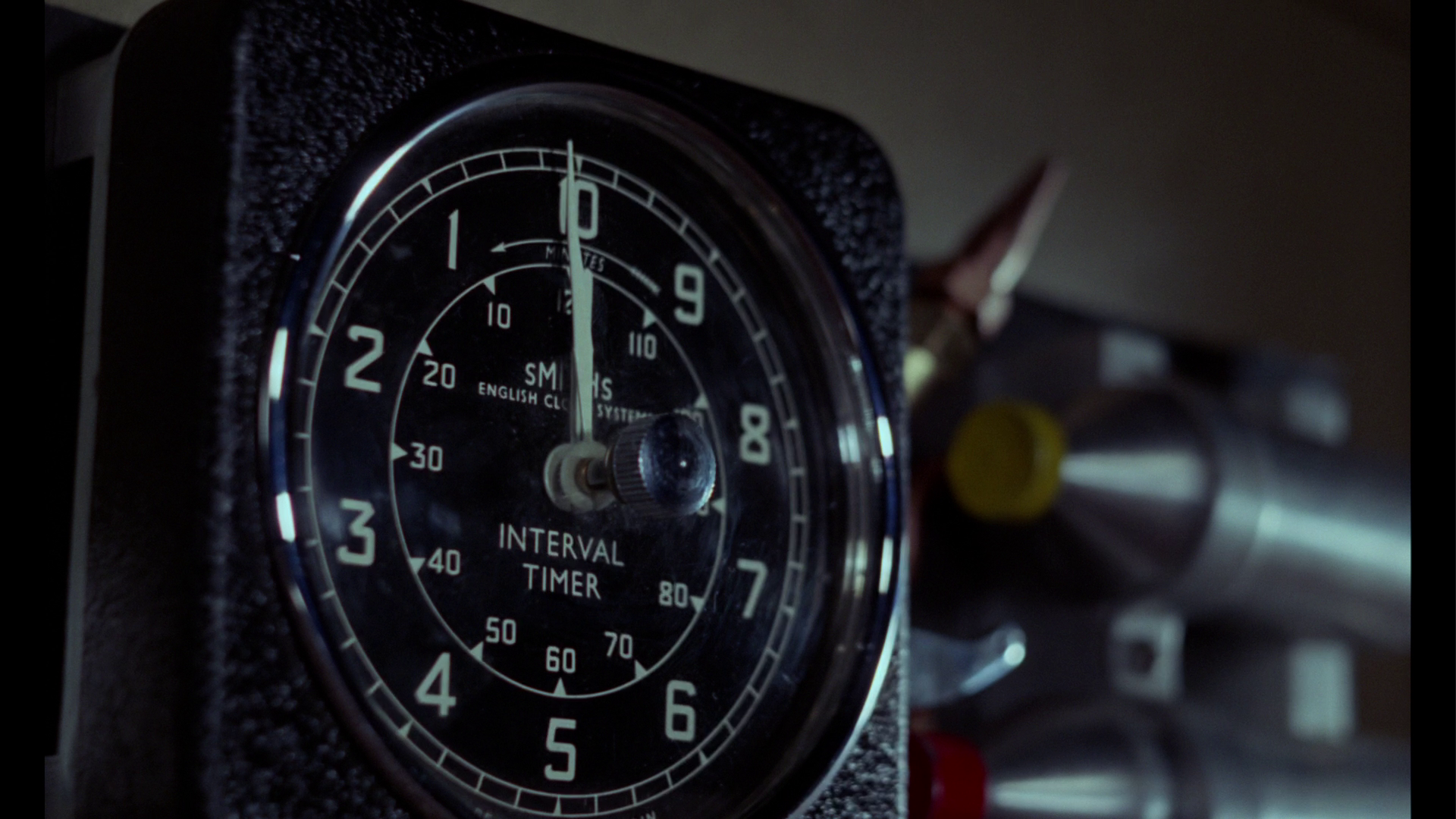

The immediacy of Yates’ staging of the car chase in Robbery was, it has been suggested, the reason why McQueen chose Yates to direct Bullitt – though the car chase in Bullitt was given a greater sense of urgency by the use of Arriflex cameras (legend has it that Bullitt was the first Hollywood film to use the Arriflex as its primary camera). Yates agreed to direct Bullitt only if he were allowed to make a couple of changes to the script and shoot on location – with the versatile and mobile Arriflex cameras used ‘to get the kind of street-level immediacy that he sought for the film’ (Pope, 2013: 92). This was especially true of the film’s central car chase, with the lightweight Arriflex cameras mounted both on and in the vehicles ‘as well as on tripods (and on the ground) adjacent to the streets’ (ibid.).  The pursuit that opens Robbery is two-pronged, with firstly the robbers lying in wait for and pursuing the car carrying the diamonds; and on the flip side, following the heist, the police spotting the fake ambulance and pursuing the thieves. In the build-up to the diamond robbery, Yates builds tension through cross-cutting between several vehicles – the target car, the fake ambulance, and the other car used by the thieves – and inserting cutaways to shots of timepieces (wristwatches, pocket watches) as in index of the importance of time to the plan, that it should run like clockwork. (The first lines of dialogue spoken in the film are between two of the thieves, Frank and Dave: ‘Any minute now’, one of them observes in relation to impending arrival of the target vehicle. ‘He could be late’, the other suggests. ‘But he isn’t’, is the reply.) The cross-cutting between the thieves in the build-up to the heist found its echo in the pivotal heist sequence in Michael Tuchner’s Villain: ‘Ram the fuckers’, snarls Richard Burton’s Vic Dakin in that film through a stocking mask. The subsequent police pursuit of the thieves in Robbery follows a similar structure, with shots from the interior of the police cars intercut with one another and shots from the radio room of the police station. The pursuit that opens Robbery is two-pronged, with firstly the robbers lying in wait for and pursuing the car carrying the diamonds; and on the flip side, following the heist, the police spotting the fake ambulance and pursuing the thieves. In the build-up to the diamond robbery, Yates builds tension through cross-cutting between several vehicles – the target car, the fake ambulance, and the other car used by the thieves – and inserting cutaways to shots of timepieces (wristwatches, pocket watches) as in index of the importance of time to the plan, that it should run like clockwork. (The first lines of dialogue spoken in the film are between two of the thieves, Frank and Dave: ‘Any minute now’, one of them observes in relation to impending arrival of the target vehicle. ‘He could be late’, the other suggests. ‘But he isn’t’, is the reply.) The cross-cutting between the thieves in the build-up to the heist found its echo in the pivotal heist sequence in Michael Tuchner’s Villain: ‘Ram the fuckers’, snarls Richard Burton’s Vic Dakin in that film through a stocking mask. The subsequent police pursuit of the thieves in Robbery follows a similar structure, with shots from the interior of the police cars intercut with one another and shots from the radio room of the police station.

Obviously inspired by the 1963 Great Train Robbery, Robbery focuses on a ruthless, macho culture of crime and, in its somber and hardboiled representation of the Great Train Robbery (or rather, the legends surrounding it) differs substantially from ‘the much more sentimental’ approach to that crime presented in Buster (David M Green, 1988) (Elliott, 2014: 63). Although shot in a very different way, in its approach to crime Robbery has much in common with American film noir heist pictures such as Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956) and Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery (1950). Robbery is a film that ‘documents a working class masculinity that populates urban spaces like the football ground, the pub, the train station and the prison’ and features men who are ‘old lags who are good at their jobs’ and demonstrate a ‘thoroughness [that] is matched with a ruthlessness that avoids the sentimental mythologising of later depictions of the train robbers’ (ibid.). In pursuit of their goal, these criminals commit acts of violence that act as ‘a reminder that the crime was an act of a determined and well-rehearsed criminal gang rather than a band of Robin Hoods’ (ibid.).  David Thomson has rather cruelly (and unarguably reductively) suggested that as a director, Yates has ‘done little more profound than send hubcaps careering round corners, but nobody did that better’ (Thomson, 2014: np). In contradiction to this perspective on Yates’ films, it could be said that Yates’ crime films, both in Britain and America, document the criminal milieu with candour and explore the politics of criminality. In this sense, the defining film within Yates’ career is possibly The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), in which Yates’ examination of the politics of crime finds its equal in the similarly-themed writing of George V Higgins. Paving the way for filmmakers like Michael Mann, Yates’ films tend to depict criminals as cold and efficient professionals: one thinks of the emotionless stare of the hitmen Frank Bullitt (Steve McQueen) chases in his Ford Mustang in Bullitt. Likewise, the criminals in Robbery are essentially technicians, and they carry out their work in a cold and clinical manner: in Film: A Modern Art, Aaron Sultanik reminds us that ‘it is the single emotional response by one of the gang members [Robinson] who calls his wife that proves their undoing’ (Sultanik, 1986: 209). David Thomson has rather cruelly (and unarguably reductively) suggested that as a director, Yates has ‘done little more profound than send hubcaps careering round corners, but nobody did that better’ (Thomson, 2014: np). In contradiction to this perspective on Yates’ films, it could be said that Yates’ crime films, both in Britain and America, document the criminal milieu with candour and explore the politics of criminality. In this sense, the defining film within Yates’ career is possibly The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), in which Yates’ examination of the politics of crime finds its equal in the similarly-themed writing of George V Higgins. Paving the way for filmmakers like Michael Mann, Yates’ films tend to depict criminals as cold and efficient professionals: one thinks of the emotionless stare of the hitmen Frank Bullitt (Steve McQueen) chases in his Ford Mustang in Bullitt. Likewise, the criminals in Robbery are essentially technicians, and they carry out their work in a cold and clinical manner: in Film: A Modern Art, Aaron Sultanik reminds us that ‘it is the single emotional response by one of the gang members [Robinson] who calls his wife that proves their undoing’ (Sultanik, 1986: 209).

The cool, clinical approach to crime – enacted by professionals – finds its corollary in the noir-tinged films polars of Jean-Pierre Melville, including the icy behaviour of hitman Jef Costello (Alain Delon) in Le samourai, released in the same year as Robbery. It’s also something which recurs throughout Yates’ later crime films. Colin McArthur has described Melville’s detailed explorations of specific criminal acts (often in sequences without dialogue, focusing on the actions of the characters rather than their words) in something which feels like ‘real time’ as a ‘cinema of process’ – ‘a cinema which went some way to honouring the integrity of actions by allowing them to happen in a way significantly closer to “real” time than was formerly the case in fictive, particularly Hollywood, cinema’ – and the term may arguably be used to describe Yates’ approach to both heists in this film (McArthur, 2000: 191). It’s an approach that McArthur suggests originated in Jacques Becker’s prison break picture Le trou (1960) and Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), and which worked its way into Hollywood via the films of Michael Mann (for example, Thief, 1981). Like Mann’s films, Robbery also features characters for whom ‘normal’ life seems intolerable, and as in pictures such as Thief (in which James Caan’s jewel thief has a car dealership as his ‘legitimate’ front – much like Dave’s clothes shop and Jack’s garage in this film) it seems that the lives of the characters outside their criminal endeavours are little more than a hollow performance: that the enactment of crime is what makes them ‘tick’. When Langdon questions Jack at the garage Jack owns, Jack tells him ‘It’s [crime is] a mug’s game, isn’t it? Well, there’s no point, now I’ve got the job and the business’. However, Jack takes little persuading to take part in the robbery of the night mail train.  Like the criminals in Mann’s films, the gang in Robbery are capitalists at heart and speak the rhetoric of capitalism. Following the diamond heist, Clifton persuades his associates to use the money they have ‘earned’ to bankroll the robbery of the night mail train. ‘That’s how it is, then’, Paul says, ‘We’ve got the capital now for investment. We all agree to go ahead’. Frank offers a weak challenge to Paul’s suggestion: ‘Why don’t we share out in the usual way?’, he asks, ‘I mean, we’re doing all right’. ‘I want us to do better, Frank’, Paul tells him before adding, ‘If there’s one thing I know: money breeds money’. (‘Mine must be on the pill’, Jack quips in response to this.) Paul is willing to give up everything for the big score: he abandons his wife Kate in a heartbeat, leaving her a note that simply says ‘Goodbye’. ‘Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner’, Robert De Niro’s Neil McAuley says in Michael Mann’s 1995 film Heat; in Robbery, Paul offers a similar piece of advice to Robinson. Robinson is pining for contact with his wife and daughter, but Paul tells him to avoid trying to reach out to them in any way as the police will have them under surveillance owing to Robinson’s status as an escaped prisoner. Paul tells Robinson that after the job, Robinson and his family will be sent to Switzerland with new passports. ‘We’d never be able to come home again’, Robinson grumbles. To this, Paul responds by declaring simply that ‘Home is a Swiss bank account’. Like the criminals in Mann’s films, the gang in Robbery are capitalists at heart and speak the rhetoric of capitalism. Following the diamond heist, Clifton persuades his associates to use the money they have ‘earned’ to bankroll the robbery of the night mail train. ‘That’s how it is, then’, Paul says, ‘We’ve got the capital now for investment. We all agree to go ahead’. Frank offers a weak challenge to Paul’s suggestion: ‘Why don’t we share out in the usual way?’, he asks, ‘I mean, we’re doing all right’. ‘I want us to do better, Frank’, Paul tells him before adding, ‘If there’s one thing I know: money breeds money’. (‘Mine must be on the pill’, Jack quips in response to this.) Paul is willing to give up everything for the big score: he abandons his wife Kate in a heartbeat, leaving her a note that simply says ‘Goodbye’. ‘Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner’, Robert De Niro’s Neil McAuley says in Michael Mann’s 1995 film Heat; in Robbery, Paul offers a similar piece of advice to Robinson. Robinson is pining for contact with his wife and daughter, but Paul tells him to avoid trying to reach out to them in any way as the police will have them under surveillance owing to Robinson’s status as an escaped prisoner. Paul tells Robinson that after the job, Robinson and his family will be sent to Switzerland with new passports. ‘We’d never be able to come home again’, Robinson grumbles. To this, Paul responds by declaring simply that ‘Home is a Swiss bank account’.

Robbery is presented here uncut, with a running time of 114:08 mins.

Video

Previously released on a disappointing DVD which presented the film full-frame (with noticeable cropping on the left and right hand edges of the frame), Robbery is presented on Network’s Blu-ray release in the 1.66:1 ratio. This would seem to be its intended aspect ratio, or as near as dammit (the film was most likely shown anywhere between 1.66:1 and 1.85:1, depending on the context of its exhibition). The wider ratio works to the film's benefit, making the compositions seem much more balanced. In this regard alone, Network's new Blu-ray is a massive improvement over the previously available DVD release of the film. The film itself takes up 19Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Previously released on a disappointing DVD which presented the film full-frame (with noticeable cropping on the left and right hand edges of the frame), Robbery is presented on Network’s Blu-ray release in the 1.66:1 ratio. This would seem to be its intended aspect ratio, or as near as dammit (the film was most likely shown anywhere between 1.66:1 and 1.85:1, depending on the context of its exhibition). The wider ratio works to the film's benefit, making the compositions seem much more balanced. In this regard alone, Network's new Blu-ray is a massive improvement over the previously available DVD release of the film. The film itself takes up 19Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

It’s a very pleasing presentation, with an impressive level of detail on display – a big step up from the DVD release. It’s a remarkably ‘clean’ presentation, with little to no damage present throughout the picture. There’s some slight softness that creeps into the image and suggests some noise reduction has been applied somewhere along the line, but it’s not a defining feature of the presentation; the large screengrabs below should give a better indication of this. Very good contrast levels are on display here, despite the ‘flat’ and naturalistic lighting of the film’s original photography, with strong mid-tones and rich, deep blacks. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clean and clear, with a strong sense of range that’s evident from the opening titles sequence’s use of Johnny Keating’s jazzy score – all horns and percussion (reminiscent of Don Ellis’ score for William Friedkin’s slightly later picture The French Connection, 1971). Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes:  - an interview with Michael Deeley (22:13). In this interview, Deeley talks about his role in the production of the film and reflects on his working relationship with Stanley Baker. Deeley also discusses in some detail the shooting of the opening car chase, and includes some amusing anecdotes in his reflections upon this. - an interview with Michael Deeley (22:13). In this interview, Deeley talks about his role in the production of the film and reflects on his working relationship with Stanley Baker. Deeley also discusses in some detail the shooting of the opening car chase, and includes some amusing anecdotes in his reflections upon this.

- an episode of Cinema focusing on the career of Stanley Baker (31:09). Originally broadcast in 1972, as part of Granada Television’s Cinema strand. Interviewed by Clive James, Baker reflects on his career in cinema to that point – both as an actor and as a producer. It’s an excellent interview, with Baker providing some fascinating comments on his own work and some of the work of those with whom he had collaborated (eg, Joseph Losey). - Behind the Scenes Footage (2:11). This is a very brief clip of Yates and his crew working on Robbery. - ‘Waiting for the Signal: The Making of Robbery’ (48:07). A documentary about the production of Robbery, this features new interviews with writer Gerald Wilson, art director Michael Seymour, production manager Gavrik Losey, and actors Michael McStay, Glynn Edwards and Barry Stanton. The interviews are candid and packed with anecdotes about the film’s production, many of which focus on Baker and his relationships with the people around him. Although there’s much praise for Yates’ work as the film’s director, Gerald Wilson expresses some dissatisfaction with the way in which his script was visualised. - The Great Train Robbery (96:20). This is the feature film edit of the 1966 German television mini-series about the Great Train Robbery (Die Gentlemen bitten zur Kasse). The original, full-length mini-series has been released on DVD in Germany. It’s a fascinating, naturalistic account of the event, rooted in the facts of the case but with some fictionalised elements. Its iconography (London landmarks, trench coats, etc) says a lot about how British culture was viewed by the mini-series’ German producers. Where the mini-series runs for approximately four hours (and is, naturally, in German), this feature film edit runs for just over ninety minutes and is dubbed (quite clumsily, it has to be said) into English. It’s slightly shorter than the running time (111 minutes) listed on the BBFC’s website for its classification before its UK cinema release in 1969, and it seems that the film may have been trimmed by its then-distributors post-classification. The film is presented in HD and takes up approximately 13Gb of space on the disc. The presentation of the film’s monochrome photography (presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio) has issues with contrast and there’s occasionally some evidence of profound decay and damage to the emulsions, but it is mostly quite stable and is certainly watchable. The English dub (presented in LPCM 2.0 mono) suffers from some instability and damage throughout, with a background crackle and hiss that makes it uncomfortable to listen to through an amplifier. - Gallery. This is a gallery of promotional imagery.

Overall

Robbery is an excellent film and gets an impressive presentation on this Blu-ray release from Network. The 1080p presentation of the main feature easily trumps the film’s previous DVD release, and is supported with some superb contextual material. It’s a great release and comes with a very strong recommendation. The inclusion of the feature film edit of Die Gentlemen bitten zur Kasse, despite the damage that’s evident within the presentation, is a marvelous ‘extra’ and ensures that this disc should be an essential purchase. Robbery is an excellent film and gets an impressive presentation on this Blu-ray release from Network. The 1080p presentation of the main feature easily trumps the film’s previous DVD release, and is supported with some superb contextual material. It’s a great release and comes with a very strong recommendation. The inclusion of the feature film edit of Die Gentlemen bitten zur Kasse, despite the damage that’s evident within the presentation, is a marvelous ‘extra’ and ensures that this disc should be an essential purchase.

References: Borden, Iain, 2012: Drive: Journeys Through Film, Cities and Landscapes. London: Reaktion Books Chibnall, Steve, 2008: ‘Carter in Context’. In: Mathijs, Ernest & Mendik, Xavier (eds), 2008: The Cult Film Reader. Open University Press: 226-40 Elliott, Paul, 2014: Studying the British Crime Film. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur Field, Matthew, 2001: Making of ‘The Italian Job’. London: Batsford McArthur, Colin, 2000: ‘Mise-en-scène degree zero: Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967)’. In: Hayward, Susan & Vincendeau, Ginette (eds), 2000: French Film: Texts and Contexts. London: Routledge: 189-201 Pope, Norris, 2013: Chronicle of a Camera: The Arriflex 35 in North America, 1945-1972. University Press of Mississippi Sultanik, Aaron, 1986: Film: A Modern Art. London: Cornwall Books Thomson, David, 2014: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. London: Abacus (Sixth Edition)  x x

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|