|

|

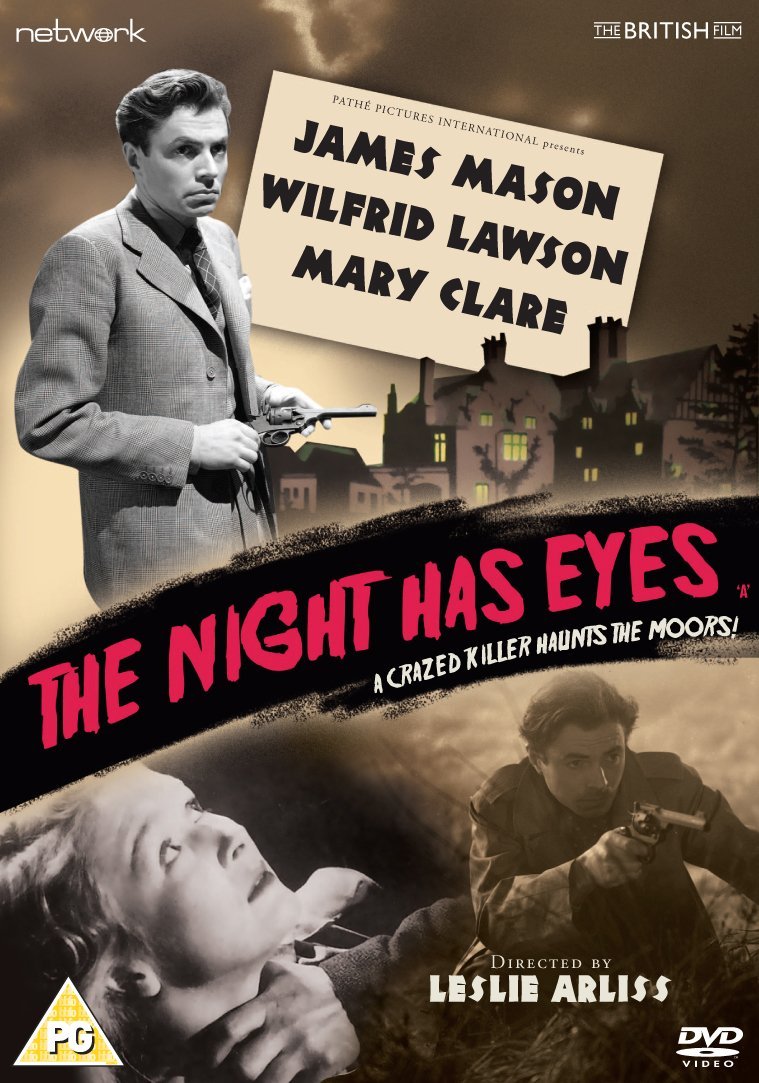

Night Has Eyes (The) AKA Moonlight Madness AKA Terror House

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (5th September 2015). |

|

The Film

The Night Has Eyes (Leslie Arliss, 1942) The Night Has Eyes (Leslie Arliss, 1942)

At the end of the school term, two young teachers from a girls school –mousy Marian (Joyce Howard) and her flirty friend Doris (Tucker Maguire) – decide to spend their holiday hiking on the Yorkshire Moors. It was there, a year earlier, that their friend and colleague Evelyn disappeared mysteriously. The deputy headmistress of the school suggests Evelyn simply found a lover and eloped with him, but Doris and Marian believe something more sinister happened to their friend. Whilst traveling on the train, they encounter a young doctor, Barry Randall (John Fernald), with whom Doris flirts outrageously. Arriving at their destination, the girls are warned by a local policeman that the ‘weather might be a bit mucky’. Barry gives them a lift partway across the moor. That evening, whilst hiking across the moors, Doris and Marian encounter stormy weather and Doris finds herself temporarily stuck in a bog. They see a house in the distance and approach it. The house’s sullen owner, Stephen Deremid (James Mason) invites them in (‘You’d better come in: there’s nowhere else you can go’, he tells the girls). Stephen is a former composer who gave up music to fight on the side of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. After suffering an injury in that conflict, he returned to Britain with a curious malady: by the light of the full moon, he suffers blackouts and, when he comes to, finds himself next to the corpse of a dead animal. Stephen is cared for by his hired help, housekeeper Mrs Ranger (Mary Clare) and groundsman Jim Sturrock (Wilfrid Lawson) – the latter of whom has a pet capuchin monkey. Fascinated with Stephen, Marian remains at the house when Barry arrives to take Doris back to the train station. However, Marian soon discovers evidence that Evelyn was present in the house on the moors, and begins to suspect that Stephen may have played a part in Evelyn’s disappearance.  Giving Doris and Marian a lift partway across the moors, Barry comments on the loneliness of the landscape, quipping ‘On my left, we have the Yorkshire Moors. On my right, we have the Yorkshire Moors’. The film emphasises the isolation of Stephen from the rest of the world, represented metonymically by the isolation of his home: ‘We never get the papers here’, Stephen tells the girls in reference to his being out of touch with current events, ‘The house is almost cut off from the world’. Stephen’s self-imposed isolation is a result in his belief that he is afflicted with a malady which turns him into a feral killer by the light of the full moon, and by his disillusionment with his former idealism. ‘I gave up music for war’, he tells Marian, ‘I had the idiotic notion that civilization was worth fighting for [….] I fought in Spain with the Republicans [….] Civilisation watched from the sidelines to ensure there should be no fair play’. Stephen’s disillusionment pushes him into curious fetishism (dressing Marian in his grandmother’s clothes) and a spiteful manner: at one point, he asks Marian cruelly ‘What have you got? No beauty, no brains. Just a lot of half-digested ideas about life picked up in a teachers’ common room’. In the spiteful quality of his character, Mason plays a similar character here to the bitter, misanthropic and cruel men he played in Arliss’ The Man in Grey (1943) and Compton Bennett’s The Seventh Veil (1945). The sexually repressed Marian becomes fascinated with this aspect of Stephen, telling him that she has ‘met men whose characters I’ve liked, whose brains I’ve admired, but who meant nothing to me. I’ve met others, brainless and brutal, you know…’ To this, Stephen interrupts by declaring, ‘Yes, I know the queer fascination with cruelty’. Giving Doris and Marian a lift partway across the moors, Barry comments on the loneliness of the landscape, quipping ‘On my left, we have the Yorkshire Moors. On my right, we have the Yorkshire Moors’. The film emphasises the isolation of Stephen from the rest of the world, represented metonymically by the isolation of his home: ‘We never get the papers here’, Stephen tells the girls in reference to his being out of touch with current events, ‘The house is almost cut off from the world’. Stephen’s self-imposed isolation is a result in his belief that he is afflicted with a malady which turns him into a feral killer by the light of the full moon, and by his disillusionment with his former idealism. ‘I gave up music for war’, he tells Marian, ‘I had the idiotic notion that civilization was worth fighting for [….] I fought in Spain with the Republicans [….] Civilisation watched from the sidelines to ensure there should be no fair play’. Stephen’s disillusionment pushes him into curious fetishism (dressing Marian in his grandmother’s clothes) and a spiteful manner: at one point, he asks Marian cruelly ‘What have you got? No beauty, no brains. Just a lot of half-digested ideas about life picked up in a teachers’ common room’. In the spiteful quality of his character, Mason plays a similar character here to the bitter, misanthropic and cruel men he played in Arliss’ The Man in Grey (1943) and Compton Bennett’s The Seventh Veil (1945). The sexually repressed Marian becomes fascinated with this aspect of Stephen, telling him that she has ‘met men whose characters I’ve liked, whose brains I’ve admired, but who meant nothing to me. I’ve met others, brainless and brutal, you know…’ To this, Stephen interrupts by declaring, ‘Yes, I know the queer fascination with cruelty’.

There’s an undercurrent of kinkiness to the film, and the script has a fairly stark sexual frankness. When Stephen tells Doris and Marian to lock the door of the room he gives them for the night, in case his housekeeper should return to work early in the morning, Doris jokes, ‘He can’t trust himself. Must be that loose manner of mine’. On the train, Doris – who is traveling with Marian in a ‘Ladies Only’ compartment – feigns an illness to attract the attention of Barry. Barry sits with Marian, telling her in reference to his entry into the ‘Ladies Only’ compartment, ‘That’s one of the advantages of having an MD after one’s name: it can get you into almost anywhere’. Barry’s happy-go-lucky disposition is contrasted sharply with Stephen’s sullen demeanour: almost immediately, Stephen tells Doris and Marian that he values ‘being alone’. Behind Stephen’s back, Doris jokes, ‘Well, give me Boris Karloff’, adding ‘You know, he looks the kind of fellow that buries his wife under the fireplace’. Later, when Stephen tells Doris and Marian not to bother looking for secret rooms or priest holes in his house, Marian jokingly compares Stephen with Bluebeard. ‘The only flaw in that story’, Stephen declares, ‘is that the rescuers arrived too early’.  As Geoff Mayer and Brian McDonnell note in their Encyclopedia of Film Noir, The Night Has Eyes ‘is a rarity as the film was produced at a time (1942) when most British and American films were focused not on the destructive physical and emotional effects of war, but on the need for communal solidarity to defeat the Axis powers’ (Mayer & McDonnell, 2007: 304). Whilst some post-Second World War films – such as Mine Own Executioner (Anthony Kimmins, 1947), recently released on Blu-ray by Network (see our review here) – explored the harmful psychological impact of war on those who participate in it (what we might now call PTSD), The Night Has Eyes stands out as an oddity in its examination of this theme within the context of a film made whilst the Second World War was still ongoing. This group of films, Andrew Spicer has argued, offered a subversive interpretation of the effects of the war that countered the ‘Blitz Myth’ (the ‘heroic story of courage, endurance and pulling together which obliterated class divisions and political allegiances’) by focusing on ‘the maladjusted veteran, the “damaged man” psychologically and ideologically unfit for peacetime civilian life, depicting the war as a traumatizing experience’ (Spicer, 2004: 167). Likewise, Robert Murphy allies Mine Own Executioner with Powell and Pressburger’s The Small Back Room: both pictures, Murphy says, contain ‘obviously war-damaged protagonists’ and ‘qualify as morbid films in their lighting style and general atmosphere’ (Murphy, 1989: 150). Similar observations could be made of The Night Has Eyes, which begins with brightly-lit scenes set in the girls school in which Doris and Marian work, but swiftly moves to the oppressive house Stephen owns on the Yorkshire Moors and takes on some of the qualities of a Gothic horror picture. As Geoff Mayer and Brian McDonnell note in their Encyclopedia of Film Noir, The Night Has Eyes ‘is a rarity as the film was produced at a time (1942) when most British and American films were focused not on the destructive physical and emotional effects of war, but on the need for communal solidarity to defeat the Axis powers’ (Mayer & McDonnell, 2007: 304). Whilst some post-Second World War films – such as Mine Own Executioner (Anthony Kimmins, 1947), recently released on Blu-ray by Network (see our review here) – explored the harmful psychological impact of war on those who participate in it (what we might now call PTSD), The Night Has Eyes stands out as an oddity in its examination of this theme within the context of a film made whilst the Second World War was still ongoing. This group of films, Andrew Spicer has argued, offered a subversive interpretation of the effects of the war that countered the ‘Blitz Myth’ (the ‘heroic story of courage, endurance and pulling together which obliterated class divisions and political allegiances’) by focusing on ‘the maladjusted veteran, the “damaged man” psychologically and ideologically unfit for peacetime civilian life, depicting the war as a traumatizing experience’ (Spicer, 2004: 167). Likewise, Robert Murphy allies Mine Own Executioner with Powell and Pressburger’s The Small Back Room: both pictures, Murphy says, contain ‘obviously war-damaged protagonists’ and ‘qualify as morbid films in their lighting style and general atmosphere’ (Murphy, 1989: 150). Similar observations could be made of The Night Has Eyes, which begins with brightly-lit scenes set in the girls school in which Doris and Marian work, but swiftly moves to the oppressive house Stephen owns on the Yorkshire Moors and takes on some of the qualities of a Gothic horror picture.

The film touches some interesting issues (the Spanish Civil War, a no-no topic in British cinema of the 1930s; the psychological cost of war) but ultimately, in its climax, retreats back into stereotypes and asserts the ‘natural’ hierarchy of the British class structure – not to mention regurgitating the usual stereotypes about rural Northerners, especially Northern members of the working classes, that were still so familiar in the 1990s/2000s to be lampooned in The League of Gentlemen (BBC, 1999-2002). The film’s attitude is sketched in the scene in which Doris and Marian disembark from their train and speak with a local policeman who warns them that the weather ‘might be a bit mucky’, and the two young women poke fun at the policeman’s accent.The film verges on camp, but it’s never less than enjoyable. The film was released in America as Terror House in 1943, and rereleased again, following Mason’s transition to Hollywood films, as Moonlight Madness in 1949. The film, as presented here, runs for 76:01 mins (PAL). The climax of the film, and the grisly comeuppance of the film's villain, are trimmed slightly in comparison with versions of the film released on DVD in the US.

Video

The Night Has Eyes was shot on small sound stages but manages to hide this well, thanks to the photography by seasoned German cinematographer Günther Krampf. The Night Has Eyes was shot on small sound stages but manages to hide this well, thanks to the photography by seasoned German cinematographer Günther Krampf.

Presented here in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio, The Night Has Eyes’ monochrome photography is presented adequately here. The source for the transfer is remarkably clean and free of damage, though there’s a softness to the image that doesn’t seem to be wholly the product of the lenses used in the shooting of the picture. Contrast is good but not great: there’s a noticeable flattening of the mid-tones in some scenes. In all, it’s a decent enough presentation, certainly watchable but pales in comparison with some of Network’s other releases of films of a similar vintage.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel Dolby Digital mono track. This is ‘clean’ throughout though sometimes dialogue is a little hard to make out (eg, in the scenes on the moors). No subtitles are included.

Extras

The sole ‘extra’ is an image gallery (1:30).

Overall

The Night Has Eyes is an interesting film, especially with regards its depiction of the effects of war on its participants. It descends into melodrama with its climax, which undoes a lot of the promise of the earlier scenes and reinforces the film’s emphasis on regional stereotypes, but on the whole it’s a well-played and very well-shot picture. This DVD release from Network offers a more than welcome chance to revisit the film, and the presentation of the picture – whilst not tip-top – is never less than watchable. Some more contextual material would have been welcome, but on the whole this is a pleasing release of a largely forgotten film, and Network are to be applauded for bringing another neglected picture to the DVD format. The Night Has Eyes is an interesting film, especially with regards its depiction of the effects of war on its participants. It descends into melodrama with its climax, which undoes a lot of the promise of the earlier scenes and reinforces the film’s emphasis on regional stereotypes, but on the whole it’s a well-played and very well-shot picture. This DVD release from Network offers a more than welcome chance to revisit the film, and the presentation of the picture – whilst not tip-top – is never less than watchable. Some more contextual material would have been welcome, but on the whole this is a pleasing release of a largely forgotten film, and Network are to be applauded for bringing another neglected picture to the DVD format.

References: Mayer, Geoff & McDonnell, Brian, 2007: Encyclopedia of Film Noir. Connecticut: Greenwood Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|