|

|

Eaten Alive AKA Death Trap AKA Horror Hotel (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th September 2015). |

|

The Film

Eaten Alive AKA Death Trap (Tobe Hooper, 1976) Eaten Alive AKA Death Trap (Tobe Hooper, 1976)

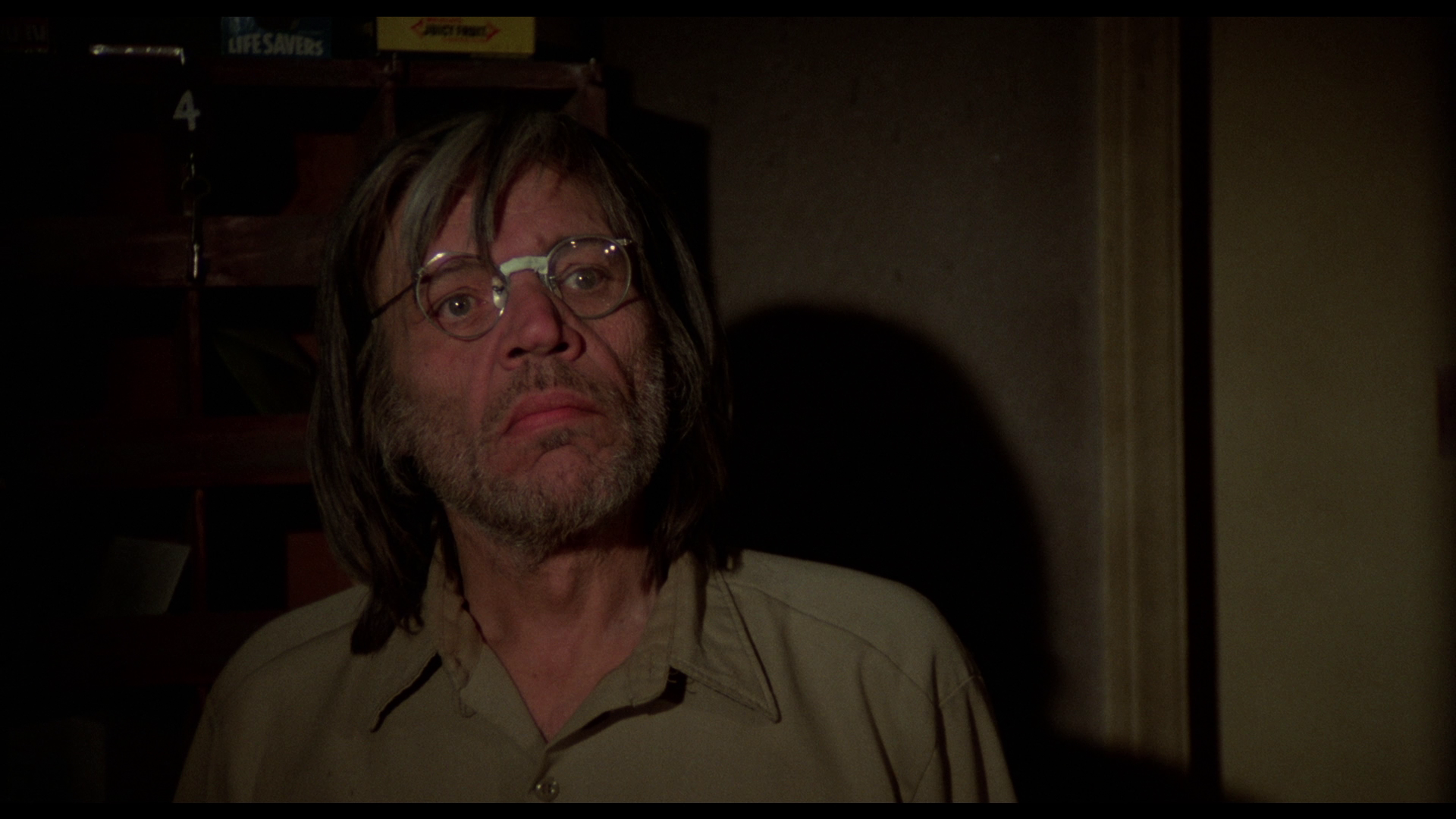

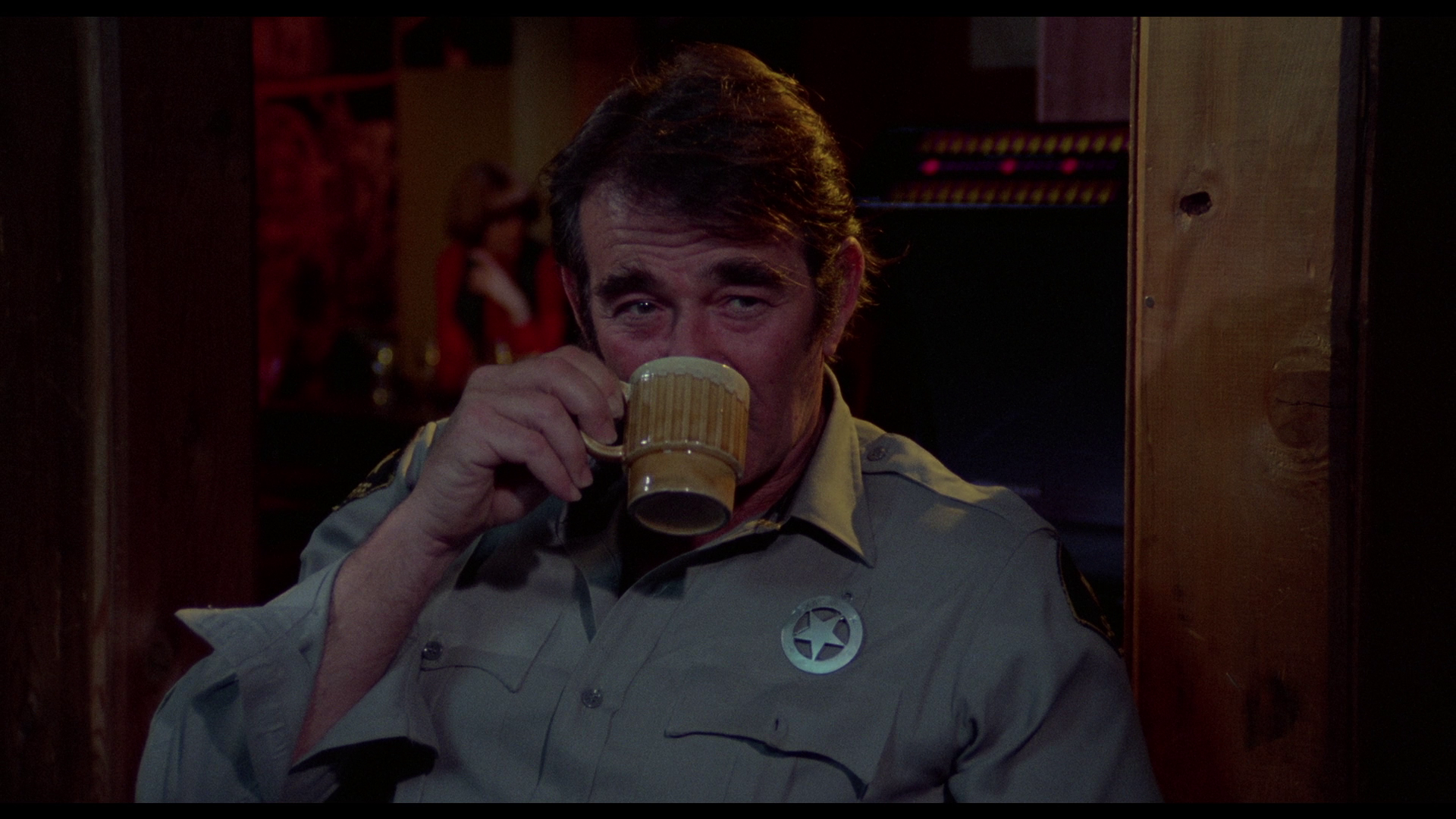

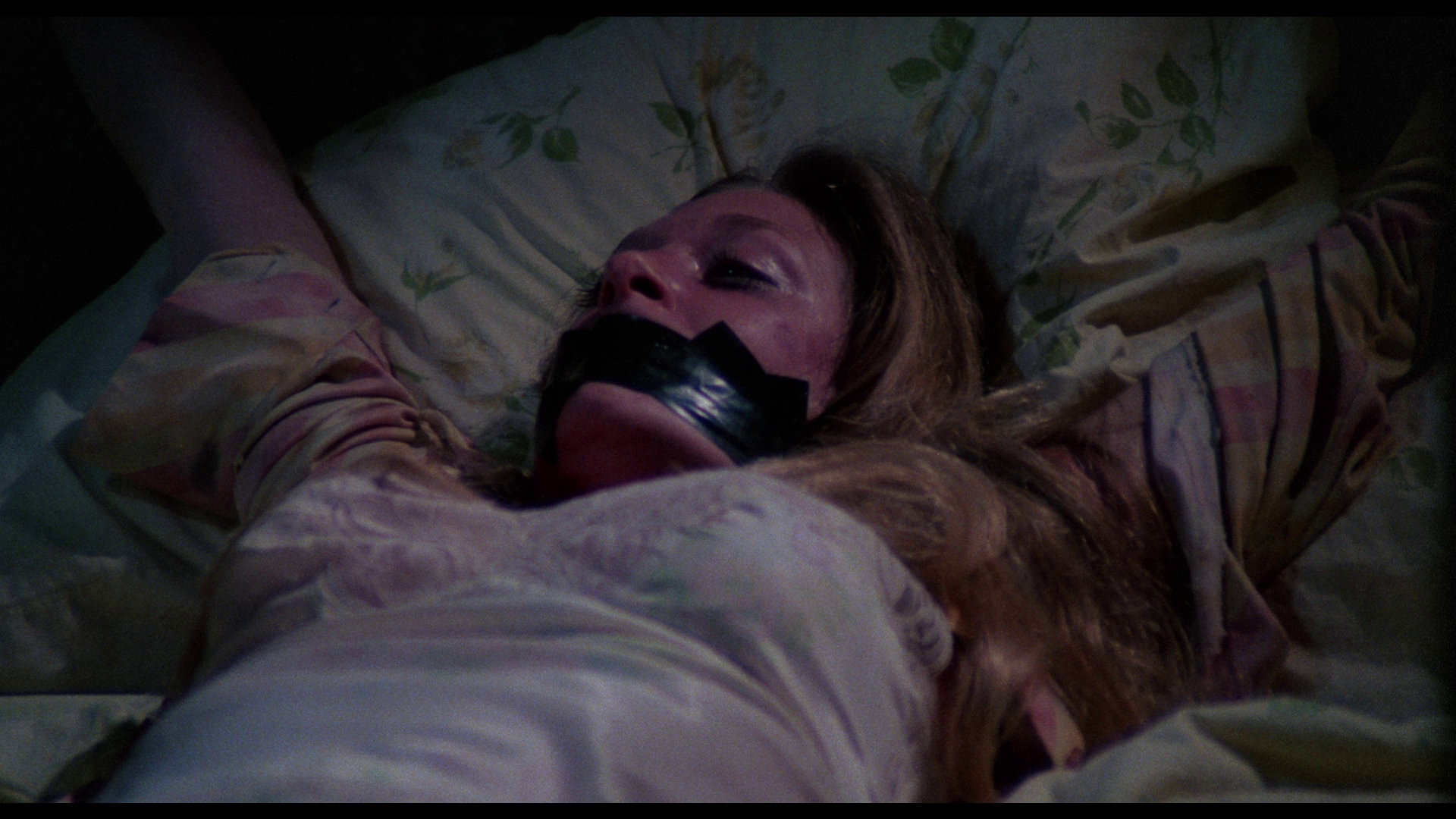

In Miss Hattie’s (Carolyn Jones) brothel, good ol’ boy Buck (Robert England) sexually assaults new prostitute Clara Wood (Roberta Collins). She flees to the isolated Starlight Hotel, which is presided over by the owner Judd (Neville Brand), an ageing war veteran with a tendency to mutter incoherently to himself and who keeps an ailing monkey and a hungry alligator – which Judd insists is instead a crocodile – as pets. (‘That old croc. Eat anything. Anything at all’, Judd tells Clara.) When Judd deduces that Clara is ‘one of Miss Hattie’s girls’, he flies into a rage and attacks her. They both tumble down the stairs, and Judd assaults Clara with a rake before feeding her to the alligator. Shortly afterwards, a family arrive at the Starlight Hotel: Roy (William Finley), his wife Faye (Marilyn Burns) and their young daughter Angie (Kyle Richards). The family appear outwardly normal, but when their pet dog Snoopy manages to enter the pen in which Judd’s alligator is kept and is eaten by the alligator in front of Angie, the family retreat to a room of the hotel in which they demonstrate some exceptionally strange behaviour. Roy rants angrily and impotently, whining like a toddler and evidencing no small amount of self-loathing (which verges on the delusional), whilst Faye acts coldly and cruelly towards both Roy and Angie. When Roy attempts to kill the alligator with his shotgun, things go awry and Judd kills Roy, feeding him to the alligator. Judd then takes Faye hostage, tying her to the bed in one of the hotel’s rooms, whilst Angie escapes into the crawlspace under the hotel. Meanwhile, Harvey Wood (Mel Ferrer) arrives at the Starlight with his daughter Libby (Crystin Sinclaire). They have travelled from Houston, Texas, and are looking for Libby’s sister Clara. They meet with Sheriff Martin (Stuart Whitman) who, once Harvey has discovered Clara was prostituting herself at Miss Hattie’s, Harvey accuses of running ‘a wide open town’. Working together, Harvey and Libby attempt to solve the mystery of Clara’s disappearance, a quest which leads them into danger.  The violence within the picture is ugly, sordid and cruel. When Judd attacks Clara with a rake, low-angle shots of the deranged Judd are intercut with close-ups of Clara as the rake slams down on her repeatedly, puncturing her torso. Clara gasps for air and makes a sound like she is drowning in her own blood. Judd then gathers her up and throws her – still alive – into the pen with the alligator. When Judd kills Roy, he beds a scythe in Roy’s stomach and the alligator breaks through the balustrade separating its pen from the walkway outside the hotel, taking Roy’s head in its jaws and dragging him into the water. Judd’s assault on Faye is equally disturbing: he attacks her in the bathroom, wrapping her in a black shower curtain and beating her around the head whilst sitting astride her until she is subdued. The violence within the picture is ugly, sordid and cruel. When Judd attacks Clara with a rake, low-angle shots of the deranged Judd are intercut with close-ups of Clara as the rake slams down on her repeatedly, puncturing her torso. Clara gasps for air and makes a sound like she is drowning in her own blood. Judd then gathers her up and throws her – still alive – into the pen with the alligator. When Judd kills Roy, he beds a scythe in Roy’s stomach and the alligator breaks through the balustrade separating its pen from the walkway outside the hotel, taking Roy’s head in its jaws and dragging him into the water. Judd’s assault on Faye is equally disturbing: he attacks her in the bathroom, wrapping her in a black shower curtain and beating her around the head whilst sitting astride her until she is subdued.

After the impact made by his second film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), Tobe Hooper. He was offered the project which evolved into Eaten Alive by producer Mardi Rustam, who along with Alvin Fast came up with the film’s basic premise – which was then developed into a workable screenplay by Hooper and Kim Henkel, with whom Hooper had written The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Though shot as Death Trap, the completed film was released under a large number of variant titles in different territories: known in America as Eaten Alive, the picture has also been released as Starlight Slaughter, Horror Hotel Massacre, Murder in the Bayou and Legend of the Bayou. The film features some amazing set design: the Starlight Hotel itself, built on a soundstage, stands out: John Kenneth Muir describes it as ‘like Tennessee Williams by way of William Girdler’ (Muir, 2008: 393). The Starlight’s status as a hotel recalls Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and the terrors held within Bates Motel but also stands distinct from it; and as Muir notes in his book about Hooper, ‘Judd’s digs looked like a real dive, not Hollywood’s sanitized conception of what a dive should look like. Cracked wallpaper, dirty toilets, torn upholstered furniture, rotting molding lumber, bad plumbing and other nasty touches made the Starlight as “real” (and disturbing) a world as Chain Saw’s memorable farmhouse’ (Muir, 2002: 19). The mise-en-scène within Judd’s rooms speaks of his past: a US flag and a Nazi flag, combined with a carbine rifle on the wall, suggest that Judd – like the actor portraying him – is a scarred veteran of the Second World War. As Muir notes, in the design of this space, as in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, ‘Hooper was expressing the “inner” insanity of his villains with strange, outward trappings’ (ibid.)  Much as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had been loosely inspired by the crimes of Ed Gein, Eaten Alive also used a grisly true crime case as the springboard for a blacker-than-black comedy. In this instance, the nebulous crimes which inspired the film were those of Joe Ball, sometimes also known as ‘the Butcher of Elmendorf’ or ‘the Bluebeard of Texas’. Ball is often considered ‘one of the first modern serial killers […] mythic kin to Ed Gein’ (Hall, 2007: 134). A bootlegger in Elmendorf, near San Antonio, Ball ‘had his way with the waitresses at his bar, and when they got pregnant, he got rid of them’, sometimes by feeding them to alligators (ibid.). In 1938, his crimes were discovered, but the exact number of his victims is impossible to identify, and thus Ball’s crimes have been the subject of much speculation (not to mention myth): as Michael Hall says, Joe Ball’s ‘tale is proof […] that people see what they want to see. Especially when it involves flesh-eating alligators’ (ibid.: 135). Much as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had been loosely inspired by the crimes of Ed Gein, Eaten Alive also used a grisly true crime case as the springboard for a blacker-than-black comedy. In this instance, the nebulous crimes which inspired the film were those of Joe Ball, sometimes also known as ‘the Butcher of Elmendorf’ or ‘the Bluebeard of Texas’. Ball is often considered ‘one of the first modern serial killers […] mythic kin to Ed Gein’ (Hall, 2007: 134). A bootlegger in Elmendorf, near San Antonio, Ball ‘had his way with the waitresses at his bar, and when they got pregnant, he got rid of them’, sometimes by feeding them to alligators (ibid.). In 1938, his crimes were discovered, but the exact number of his victims is impossible to identify, and thus Ball’s crimes have been the subject of much speculation (not to mention myth): as Michael Hall says, Joe Ball’s ‘tale is proof […] that people see what they want to see. Especially when it involves flesh-eating alligators’ (ibid.: 135).

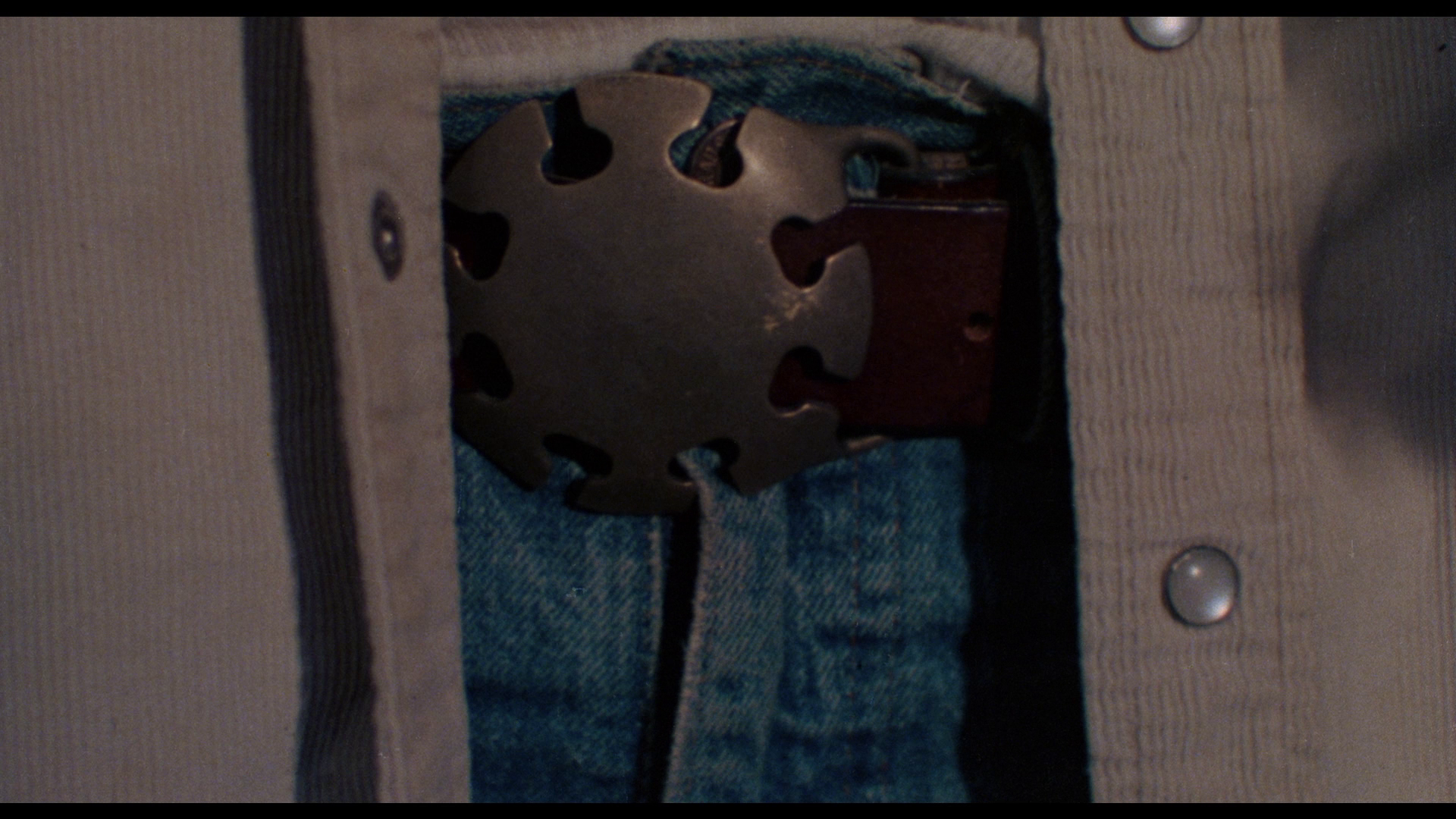

The alligator Judd keeps, which he insists is a crocodile, is balanced by the monkey which he also keeps in a cage. The monkey was, according to Hooper, a creature which had appeared in a number of films, and its slow death was captured during the shooting of Eaten Alive. The juxtaposition of the two creatures, very different in temperament, is done very deliberately: shots of the alligator, which we are reminded through the film’s dialogue is responsible for the loss of one of Judd’s legs, are contrasted through the film’s editing with shots of the caged monkey. This rhythm within the construction of the picture hints at something symbolic, perhaps two aspects of Judd’s character or, more widely, mankind’s relationship with nature: the caged beast in contrast with the alligator that cannot be controlled or contained; some animals can be tamed, but others can’t. Likewise, the swamp is a wilderness, an untamed landscape, and the Starlight Hotel is a small man-made oasis within it – but of course that too is eventually overrun by nature, when the alligator breaks free of its pen and devours the owner, Judd. As Judd rants to himself following the scene in which the alligator eats Snoopy, ‘Things happen. All according to instincts. There ain’t no… There ain’t no distinctions. Distinctions. None at all. You do what… What you gotta do’. Like Leatherface in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Eaten Alive’s Judd is a (at least partially) sympathetic villain – though unlike Leatherface, of course, Judd’s face isn’t hidden behind a mask. The parallels between the farmhouse in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and the Starlight Hotel in Eaten Alive (and, for that matter, the titular funhouse in Hooper’s 1981 picture The Funhouse) are clear enough: both represent recognisable archetypal buildings of the rural south, and hide within them an unexpected brutality and the use of human corpses as food (though in contrast with the cannibalism suggested within The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, in Eaten Alive the victims are of course food for Judd’s alligator). Both films also build to a crescendo: a prolonged, nerve-jangling sequence of screaming and agony. In The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, this takes place when the cannibalistic Sawyer family tie Sally (Marilyn Burns) to a chair with the intention of killing her slowly, and Sally screams persistently. In Eaten Alive, Hooper cross-cuts the prolonged peril experienced by Angie, the little girl trapped in the crawlspace under the hotel and threatened by Judd’s alligator; the sheer panic of Faye, who is tied to the bed in one of the rooms and, aware of the danger in which Angie finds herself, screams as persistently as Sally in Hooper’s previous film; the sexual encounter between Buck and Lynette (Janus Blythe) and Buck’s gradual realisation that he can hear Angie’s screams (resulting in Buck’s death); Libby’s return to the hotel and her discovery of Faye.  Reynold Humphries has suggested that a major theme within Eaten Alive is the issue of male sexuality, ‘a theme approached with care and subtlety by Hooper’ (Humphries, 2002: 126). This is established in the film’s opening sequence, which begins with a close-up of Buck’s belt buckle as he undoes it, and juxtaposes this with a close-up of Clara’s face. She watches impassively. Following this, the close-up of Buck’s belt buckle and the close-up of Clara are superimposed over one another as, offscreen, Buck speaks the film’s first line of dialogue: ‘Name’s Buck, and I’m rarin’ to fuck’. (Later, when Buck meets Faye, he introduces himself: ‘How’d you do, ma’am. Name’s Buck…’ The line is left hanging, Buck’s previous introduction and his perception of himself as a ‘stud’ going unstated, adding a perverse undercurrent to the scene. The line acts a dark reminder of Buck’s sexual sadism: his greeting of Faye may seem outwardly polite, but behind it is the man who sexually abused Clara a few scenes earlier.) In response, Clara simply states: ‘Just get it over with’. Buck then reduces Clara to the level of an animal, describing her as a ‘Nice lookin’ filly’ before assuring her that he wants his money’s worth. He puts her on all fours and attempts to fuck her anally, promising her that ‘I’m gonna ride you like you’ve never been rode before [….] There ain’t no such word as “no”, you understand?’ Luckily, Clara manages to make her escape – although Miss Hattie, when she enters the room wondering what the commotion is about, seems more interested in appeasing Buck, her paying customer, by offering him two more members of her ‘stable’ rather than consoling Clara. (Miss Hattie tells Clara unsympathetically, ‘You don’t want to work? You just pack your bags and get out of here’.) The economic imperative dominates – perhaps reminding a viewer of Hooper’s viciously satirical depiction of the yuppies in the opening sequence of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and his blackly comic deconstruction of the spirit of capitalist enterprise in that picture. Eaten Alive in this sense bridges the depiction of cannibalism in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (in which the consumption of human flesh is the result of the Sawyer family – unemployed slaughterhouse workers – responding to their poverty at the hands of capitalism) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (in which the consumption of human flesh is employed by the Sawyers as a business strategy). Reynold Humphries has suggested that a major theme within Eaten Alive is the issue of male sexuality, ‘a theme approached with care and subtlety by Hooper’ (Humphries, 2002: 126). This is established in the film’s opening sequence, which begins with a close-up of Buck’s belt buckle as he undoes it, and juxtaposes this with a close-up of Clara’s face. She watches impassively. Following this, the close-up of Buck’s belt buckle and the close-up of Clara are superimposed over one another as, offscreen, Buck speaks the film’s first line of dialogue: ‘Name’s Buck, and I’m rarin’ to fuck’. (Later, when Buck meets Faye, he introduces himself: ‘How’d you do, ma’am. Name’s Buck…’ The line is left hanging, Buck’s previous introduction and his perception of himself as a ‘stud’ going unstated, adding a perverse undercurrent to the scene. The line acts a dark reminder of Buck’s sexual sadism: his greeting of Faye may seem outwardly polite, but behind it is the man who sexually abused Clara a few scenes earlier.) In response, Clara simply states: ‘Just get it over with’. Buck then reduces Clara to the level of an animal, describing her as a ‘Nice lookin’ filly’ before assuring her that he wants his money’s worth. He puts her on all fours and attempts to fuck her anally, promising her that ‘I’m gonna ride you like you’ve never been rode before [….] There ain’t no such word as “no”, you understand?’ Luckily, Clara manages to make her escape – although Miss Hattie, when she enters the room wondering what the commotion is about, seems more interested in appeasing Buck, her paying customer, by offering him two more members of her ‘stable’ rather than consoling Clara. (Miss Hattie tells Clara unsympathetically, ‘You don’t want to work? You just pack your bags and get out of here’.) The economic imperative dominates – perhaps reminding a viewer of Hooper’s viciously satirical depiction of the yuppies in the opening sequence of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and his blackly comic deconstruction of the spirit of capitalist enterprise in that picture. Eaten Alive in this sense bridges the depiction of cannibalism in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (in which the consumption of human flesh is the result of the Sawyer family – unemployed slaughterhouse workers – responding to their poverty at the hands of capitalism) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (in which the consumption of human flesh is employed by the Sawyers as a business strategy).

Like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and its sequel, Eaten Alive contains a sympathetic depiction of women under patriarchy. Buck’s sexual humiliation of Clara and his preference for the ‘deviant’ practice of anal penetration marks him as animalistic, and Buck’s abuse of Clara is mirrored, following her flight from Miss Hattie’s brothel to the Starlight Hotel, by her savage murder at the hands of Judd which is in turn followed by her use as alligator feed. As Humphries suggests, later in the film, when Buck and Lynette retreat to the Starlight Hotel and use one of the rooms for their tryst, ‘[t]he way Buck positions [Lynette’s] body on the bed recalls the position of the imprisoned wife [Faye]’: both Judd and Buck position women as objects and abuse them (ibid.). ‘Thus the female body as sexual object becomes an object for real consumption’, Humphries argues, ‘with an implicit parallel being drawn between the behaviour of the client [Buck] […] and [the murderer] Judd’ (ibid.) The film’s original title, Death Trap, thus becomes representative of both the alligator and ‘surely also to the destructive dimension of male desire when thwarted’ (ibid.).  Throughout the film, Hooper demonstrates a sympathy for his female characters. On the other hand, other than Sheriff Martin (who, it can be said, is mostly ineffectual despite being well-intentioned) the film’s male characters are depicted as deviant or at the very least deeply troubled. Buck is seemingly addicted to casual (or paid for) sexual encounters and prefers to humiliate women and to fuck them anally. Roy, played with an escalating sense of mania by William Finley, enters the film as what appears to be a good father but after the dog is eaten rapidly demonstrates a sense of self-loathing and retreats into delusions. ‘I don’t know what you want me to do’, Roy whines after Snoopy is eaten by the alligator. ‘Nothing’, Faye tells him coldly, ‘I don’t expect you to do nothing’. (The double negative seems intentional.) We are told that Roy has recently lost his job, and therefore his status as the family’s breadwinner – and his masculinity itself – is in doubt. Roy finally makes the decision to ‘prove’ himself and takes his shotgun out of the family’s car, promising to shoot the alligator. ‘Daddy’s off to slay the dragon’, Faye tells Angie. Judd himself is a quiet, peaceful man but, of course, within his personality is a madness, perhaps induced by his wartime experiences or perhaps predating them, that is brought on by the smallest hint of sexuality (represented through his denouncement of Miss Hattie’s brothel) which leads to murder. Finally, Harvey Wood, obsessed with finding his daughter Clara, is blind to reason and too quick to judge. Throughout the film, Hooper demonstrates a sympathy for his female characters. On the other hand, other than Sheriff Martin (who, it can be said, is mostly ineffectual despite being well-intentioned) the film’s male characters are depicted as deviant or at the very least deeply troubled. Buck is seemingly addicted to casual (or paid for) sexual encounters and prefers to humiliate women and to fuck them anally. Roy, played with an escalating sense of mania by William Finley, enters the film as what appears to be a good father but after the dog is eaten rapidly demonstrates a sense of self-loathing and retreats into delusions. ‘I don’t know what you want me to do’, Roy whines after Snoopy is eaten by the alligator. ‘Nothing’, Faye tells him coldly, ‘I don’t expect you to do nothing’. (The double negative seems intentional.) We are told that Roy has recently lost his job, and therefore his status as the family’s breadwinner – and his masculinity itself – is in doubt. Roy finally makes the decision to ‘prove’ himself and takes his shotgun out of the family’s car, promising to shoot the alligator. ‘Daddy’s off to slay the dragon’, Faye tells Angie. Judd himself is a quiet, peaceful man but, of course, within his personality is a madness, perhaps induced by his wartime experiences or perhaps predating them, that is brought on by the smallest hint of sexuality (represented through his denouncement of Miss Hattie’s brothel) which leads to murder. Finally, Harvey Wood, obsessed with finding his daughter Clara, is blind to reason and too quick to judge.

Following The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Hooper had a turbulent relationship with his producers, being fired from both Venom (eventually directed by Piers Haggard, 1981) and The Dark (John ‘Bud’ Carlos, 1979) and experiencing conflict during the production of The Funhouse. Eaten Alive was no exception: Hooper reputedly left the picture before shooting had finished, and in his absence it was completed by Carolyn Jones and Michael Brown, the film’s editor. Hooper’s departure was said to have been a response to conflict with Mardi Rustam, who apparently saw the picture as a comedy (whereas Hooper wanted to make something much more unsettling) and demanded that more nudity be included in it (Muir, 2002: 19). After Hooper’s departure, the nude scenes were filmed. Robert Englund once suggested that the producers ‘pestered’ Hooper ‘and violated his sense of rhythm’, leading to Hooper leaving ‘the movie under rather unpleasant circumstances’ (Englund, quoted in ibid.).  When released in the UK as Death Trap, Eaten Alive was cut by the BBFC and released with a running time of just over 87 minutes. The film had both cut (from VCL) and uncut (from Vipco) VHS releases in the pre-VRA era, the latter of which appeared on the DPP’s list of ‘video nasties’ – titles which were considered likely to be found obscene if prosecuted. However, Death Trap was never successfully prosecuted and was eventually dropped from the ‘video nasties’ list in 1985. Subsequently, Vipco released the film again on VHS in 1992, in a version that suffered BBFC cuts of 25 seconds to Judd’s attempted sexual assault on Clara and some of the more outrageous moments of violence (notably the scene of one character with a scythe embedded through their neck, and Judd’s use of a rake in the protracted murder of Clara). The film was finally passed uncut by the BBFC in 2000 for yet another VHS release from Vipco – who later released Death Trap on DVD (in 2003) in the same uncut form. This new Blu-ray release from Arrow is, of course, totally uncut and has a running time of 90:53 mins. When released in the UK as Death Trap, Eaten Alive was cut by the BBFC and released with a running time of just over 87 minutes. The film had both cut (from VCL) and uncut (from Vipco) VHS releases in the pre-VRA era, the latter of which appeared on the DPP’s list of ‘video nasties’ – titles which were considered likely to be found obscene if prosecuted. However, Death Trap was never successfully prosecuted and was eventually dropped from the ‘video nasties’ list in 1985. Subsequently, Vipco released the film again on VHS in 1992, in a version that suffered BBFC cuts of 25 seconds to Judd’s attempted sexual assault on Clara and some of the more outrageous moments of violence (notably the scene of one character with a scythe embedded through their neck, and Judd’s use of a rake in the protracted murder of Clara). The film was finally passed uncut by the BBFC in 2000 for yet another VHS release from Vipco – who later released Death Trap on DVD (in 2003) in the same uncut form. This new Blu-ray release from Arrow is, of course, totally uncut and has a running time of 90:53 mins.

Video

Based on a new 2k scan of the film’s negative, this 1080p presentation of the film, using the AVC codec, is in the picture’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and fills approximately 23Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The saturated colour palette of the picture is communicated excellently via this HD presentation of the film, a significant improvement over Dark Sky’s US DVD release – which was to this point the film’s most pleasing home video release of Eaten Alive. The presentation on Arrow’s Blu-ray evidences a remarkable colour consistency throughout and a superb level of detail. The image suffers from a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment of very slight density fluctuation at the 44 minute mark (look at the blue wallpaper behind Brand), which is most likely owing to the state of the materials used as the basis for the transfer, but it’s barely noticeable and won’t distract from anyone’s enjoyment of the film. Excellent contrast levels result in a very pleasingly-balanced image, handling the film’s many nighttime sequences superbly. The improvement in contrast levels on this release, compared with the film’s previous home video releases, shows how much of the film’s photography is dependent on the expressionistic use of shadows for effect. A strong encode ensures the film has the texture of 35mm film. Based on a new 2k scan of the film’s negative, this 1080p presentation of the film, using the AVC codec, is in the picture’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and fills approximately 23Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The saturated colour palette of the picture is communicated excellently via this HD presentation of the film, a significant improvement over Dark Sky’s US DVD release – which was to this point the film’s most pleasing home video release of Eaten Alive. The presentation on Arrow’s Blu-ray evidences a remarkable colour consistency throughout and a superb level of detail. The image suffers from a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment of very slight density fluctuation at the 44 minute mark (look at the blue wallpaper behind Brand), which is most likely owing to the state of the materials used as the basis for the transfer, but it’s barely noticeable and won’t distract from anyone’s enjoyment of the film. Excellent contrast levels result in a very pleasingly-balanced image, handling the film’s many nighttime sequences superbly. The improvement in contrast levels on this release, compared with the film’s previous home video releases, shows how much of the film’s photography is dependent on the expressionistic use of shadows for effect. A strong encode ensures the film has the texture of 35mm film.

In all, it’s an utterly superb presentation of the film. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review, including some comparing this release with Dark Sky’s DVD release of the picture. As you'll note, aside from the bump in detail and improved contrast levels, the Arrow presentation also opens up the framing slightly in comparison with the Dark Sky DVD release - especially on the right hand side of the frame.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 1.0 mono track, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The LPCM track is clean and clear, the nerve-shredding screams and atonal electronic music (composed by Hooper and Wayne Bell) almost enough to cause a migraine in the viewer. It’s a soundscape which, like that of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, may be best described as ‘combative’. The opening shot of the moon, accompanied by the electronic doodlings of the film’s soundtrack, sets the viewers nerves on edge from the start – much like the discordant music with which The Texas Chain Saw Massacre opens. Even the soft country ballads which play persistently on the radio in Judd’s room (and in the redneck bar in which Buck struts his stuff) wear the viewer down by their utter insistence – and offer a blackly comic counterpoint to the onscreen action. (One of the songs Judd listens to is entitled ‘A Cowboy is True to His Word’.) Brad Stevens has suggested that the insistent use of country and western music in Eaten Alive, through its association of Judd ‘with the heroes of Western mythology’ (cowboys), connects the picture with the family in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre who are ‘the true inheritors of America’s pioneer tradition’ and the use of cowboy iconography in the abandoned amusement park that the Sawyers make their home in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Stevens, 2003: 12-3).

Extras

The disc includes an impressive array of contextual material.  - Commentary with Mardi Rustam, Roberta Collins, William Finley, Kyle Richards and Craig Reardon. This commentary, featuring the film’s producer (Rustam), three of its actors (Collins, Finley and Richards) and the makeup effects artist on the production (Reardon) is fascinating. It’s the same commentary that was included on Dark Sky’s DVD release of the picture in the States. The commentators are interviewed separately, and their comments are presented over the pertinent scenes – much like the Criterion Collection’s commentary tracks from the LaserDisc era. Of the interviewees, Rustam and Reardon provide the most information, with Rustam offering a mostly technical account of the film’s production, whilst Reardon delivers some highly amusing anecdotes. - Commentary with Mardi Rustam, Roberta Collins, William Finley, Kyle Richards and Craig Reardon. This commentary, featuring the film’s producer (Rustam), three of its actors (Collins, Finley and Richards) and the makeup effects artist on the production (Reardon) is fascinating. It’s the same commentary that was included on Dark Sky’s DVD release of the picture in the States. The commentators are interviewed separately, and their comments are presented over the pertinent scenes – much like the Criterion Collection’s commentary tracks from the LaserDisc era. Of the interviewees, Rustam and Reardon provide the most information, with Rustam offering a mostly technical account of the film’s production, whilst Reardon delivers some highly amusing anecdotes.

- An optional introduction by Tobe Hooper (0:20). This new introduction by Hooper features the director hoping the film’s viewers ‘enjoy the colours’. Newly-Filmed Interviews: - Tobe Hooper (14:02). Hooper references the fairy tales of Grimm as an inspiration on his films, and suggests that Eaten Alive particularly ‘takes place in a surrealistic twilight world’ – aided by the film’s use of a sound stage for the exteriors of the Starlight Hotel as a means of ‘creat[ing] an unreal world’. Prior to Eaten Alive, Hooper had completed a screenplay based on a real-life murder case and struggled to get financing for it. He was approached with the project that evolved into Eaten Alive, which offered him his first experience of being invited to read someone else’s script. The original script, he says, focused on a hotel which offered people the chance to pay to watch the feeding of a crocodile – unaware that the feed being offered to the creature was ‘cannibal stew meat’. Some of the elements within the film he drew from his own experience, such as Miss Hattie’s brothel – which was loosely based on a real brothel that was ‘protected’ (presumably by the mob) and situated outside Austin, Texas. Hooper talks about the shooting of the film, and how different the production was to his earlier films (Eggshells and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre) – because on those films he had become accustomed to lightweight cameras such as Arriflexes ‘which you could pick them up and move them’. Eaten Alive was shot instead on ‘an old “blimped” Mitchell’ which was ‘the size of a car’, ‘and I couldn’t make things move as fast as I’d been used to’.  The film was ‘scripted pretty completely’ and had a central character who snorted ‘BC headache powder’. The performances were balanced between the ‘theatrical’ (Englund, Finley) and the ‘straight on’ (Brand, Whitman, Ferrer). ‘There was something about that croc and that monkey’, Hooper says, and ‘the monkey knew it was time for it to die. There was some kind of strange energy’. The monkey had ‘been used in too many other films’ and consequently ‘didn’t quite pass outright’, and Hooper suggests that its expiration most likely couldn’t be included in a picture today owing to the laws surrounding animal cruelty on film. The film was ‘scripted pretty completely’ and had a central character who snorted ‘BC headache powder’. The performances were balanced between the ‘theatrical’ (Englund, Finley) and the ‘straight on’ (Brand, Whitman, Ferrer). ‘There was something about that croc and that monkey’, Hooper says, and ‘the monkey knew it was time for it to die. There was some kind of strange energy’. The monkey had ‘been used in too many other films’ and consequently ‘didn’t quite pass outright’, and Hooper suggests that its expiration most likely couldn’t be included in a picture today owing to the laws surrounding animal cruelty on film.

The script contained much more content not included in the finished film: for example, Buck was to have a gang whose conflict with Judd led to a major climax. However, ‘Almost half of the way through the film’, Hooper began to feel a strong sense of interference, of ‘having suggestions imposed on me that didn’t jive with my true line’. This led to a lot of arguments between Hooper and Rustam which led to Hooper leaving the set a number of times. Hooper reflects on his career, and says that he didn’t consider each individual film more important than a sense of having a ‘career’: he’s ‘sort of myopic’, he says, ‘in that I’m only thinking about that [the film he’s working on at the moment]’. He also says that he learnt a lot about filmmaking from seeing films regularly at the drive-ins of Austin, Texas, and suggests that there’s much to be learnt from seeing ‘bad films’. - Janus Blythe (11:37). Blythe discusses her role in the film and talks a little about the changes that were made to the picture following Hooper’s departure: Blythe’s scenes were shot after Hooper left, apparently, which was a great disappointment to her owing to the fact that she was excited at the prospect of working with Hooper. She also discusses some of her other film performances, including The Hills Have Eyes (Wes Craven, 1977) and The Incredible Melting Man (William Sachs, 1977). She also discusses her talk show, The Janus Blythe Show. - Craig Reardon (11:25). Reardon says his cinephilia is owed to being exposed to horror films on television and was influenced by the work of classic makeup artists such as Jack Pierce. He was approached to work on Eaten Alive after the original makeup artist was expelled owing to dissatisfaction with his work. He discusses the history of the studio on which the film was made, which was ‘old and it was ramshackle’ but had been used by John Ford on The Informer and had also been used to shoot some of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe pictures. Reardon says that the period had ‘a kind of like a seasick quality’, and the paradigms of many of the genres (and the industry) were undergoing ‘seismic shift[s]’. He discusses the success of the AIP pictures as ‘starting to sort of sputter out’ during the era, alongside the production of ‘these big Hollywood films such as Love Story’; ‘there was also the ascendancy of the “downer” ending, which began to permeate movies entirely’. This period led to the success of Star Wars in 1977, because ‘it was the return of the triumphant good guy over the bad guy’ after a period of ‘“here’s more reality… shitty, isn’t it”’ films. There was ‘a sense of despair, and a sense of almost nihilism’ that was reflected in some Hollywood films and is particularly evident in Hooper’s pictures of the period. The film is so bleak, and its setting so gritty ‘that it almost becomes a kind of metaphor for something’. Horror films survive on a ‘sense of dread’ and an ‘intimation of something else’. There was a sense that ‘we’re losing everything America wanted’ and there was also much tension within American society – plus the impact of the Manson murders – led to the horror pictures of the era ‘represent[ing] a kind of tearing apart of the cosmos’.  Reardon also discusses Brand’s persona: his status as a war veteran who took up acting as ‘a part of the therapy’ following his wartime experiences, his well-documented problems with alcohol, and his tough guy attitude. By the time he appeared in Eaten Alive ‘he was sort of sand-blasted’ and was utterly believable as the killer Judd, giving him ‘the perfect vehicle to be socially acceptable but to manage […] rage’. Where Hooper was ‘quiet’, Brand was ‘expansive’ but both ‘arrive[d] at their art through interior means’: Hooper doesn’t talk extensively about ‘motivation’ but usually uses ‘simple short-hand’ on the set, but there was an ‘awful lot of rational thinking going on’ about the symbolism of colours and set decoration, etc. Brand, on the other hand, had a gregarious personality but also evidenced much interiority in his craft. Reardon also discusses Brand’s persona: his status as a war veteran who took up acting as ‘a part of the therapy’ following his wartime experiences, his well-documented problems with alcohol, and his tough guy attitude. By the time he appeared in Eaten Alive ‘he was sort of sand-blasted’ and was utterly believable as the killer Judd, giving him ‘the perfect vehicle to be socially acceptable but to manage […] rage’. Where Hooper was ‘quiet’, Brand was ‘expansive’ but both ‘arrive[d] at their art through interior means’: Hooper doesn’t talk extensively about ‘motivation’ but usually uses ‘simple short-hand’ on the set, but there was an ‘awful lot of rational thinking going on’ about the symbolism of colours and set decoration, etc. Brand, on the other hand, had a gregarious personality but also evidenced much interiority in his craft.

All of these interviews are illustrated with some great on-set stills. Archive Interviews (these are carried over from Dark Sky’s DVD release of the film): - Tobe Hooper (19:38). Hooper reflects on how he became involved in the project after the creative drought which seemed to follow the success of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. He also talks at length about the shooting of the picture, including the fake alligator used on the set, and his relationships with the film’s cast members. - Robert Englund (15:05). Englund speaks generally about his career and how he became involved in Eaten Alive – which was his first role in a horror picture, the genre with which he would become closely associated throughout the rest of his career owing to his performance as Freddy Krueger in Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). - Marilyn Burns (5:18). This is a breezy interview with the now-late Burns, who talks enthusiastically about the film’s other cast members and her pleasure at working with some great veterans of film acting. The Butcher of Elmendorf (23:05) is an interesting account of the crimes of Joe Ball, the killer who inspired Eaten Alive. Trailers (these are a series of trailers for the film under some of its different titles): - Green Band (‘Death Trap’) (1:06) - Red Band (‘Death Trap’) (2:10) - Green Band (‘Eaten Alive’) (1:12) - Red Band (‘Eaten Alive’) (2:14) - ‘Starlight Slaughter’ (2:43) - ‘Horror Hotel’ (1:42) - Japanese trailer (‘Death Trap’) (2:28) TV and Radio Spots: - ‘Starlight Slaughter’ TV spot 1 (0:36) - ‘Starlight Slaughter’ TV spot 2 (0:36) - ‘Eaten Alive’ radio spot 1 (0:36) - ‘Eaten Alive’ radio spot 2 (1:04) Alternate Credits (1:04). These credits are for the film’s release under the Death Trap title. Galleries: - Behind the Scenes (8:09): images from the production of the film. - Stills and Promo (1:01): a collection of posters and lobby cards. - Comment Cards (0:32): digital reproductions of some of the comments made by the audience during a preview screening of the picture. The disc also includes one of Arrow’s lavish and oh-so-pretty booklets which is illustrated with stills from the film and includes a typically insightful essay about the picture by Brad Stevens.

Overall

I don’t think there’s any shame in saying that Tobe Hooper is one of my favourite American horror film directors: he’s made some stinkers, but his strongest work stands amongst the best of US horror filmmaking. Eaten Alive is also my favourite Hooper film, which is perhaps a more controversial stance to take – especially considering, the seemingly unassailable status of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre aside, that it’s not completely the work of Hooper. Nevertheless, despite the film’s fairytale-like aspects (the trapping of Angie in the crawlspace beneath the hotel, the garish EC Comics-like colour scheme) there’s a brutal reality to the picture which is encapsulated in its depiction of violence as sudden yet protracted, the cruelty feeling very ‘real’ despite the trappings of the fantastical that surround it. Additionally, there’s a naturalism to the depiction of the Starlight Hotel which perhaps, as has been suggested in the past, comes from Hooper’s own youth (his parents were hotel managers). Overwhelmingly, the film has an oppressive atmosphere, and it’s a bitter, nihilistic picture that is shot through with a blackly comic sensibility. In many ways, as suggested above, it bridges the two Texas Chain Saw Massacre pictures that Hooper made and reminds us that the first Texas Chain Saw Massacre is as much a black comedy as a horror picture – something which is often overlooked in discussions of the film itself, and which is foregrounded in the sequel. Like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Eaten Alive has a brutal, fast climax that ends abruptly and emphasises the cruelty of nature (both in the broader sense, and in the sense that it applies to the human animal). I don’t think there’s any shame in saying that Tobe Hooper is one of my favourite American horror film directors: he’s made some stinkers, but his strongest work stands amongst the best of US horror filmmaking. Eaten Alive is also my favourite Hooper film, which is perhaps a more controversial stance to take – especially considering, the seemingly unassailable status of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre aside, that it’s not completely the work of Hooper. Nevertheless, despite the film’s fairytale-like aspects (the trapping of Angie in the crawlspace beneath the hotel, the garish EC Comics-like colour scheme) there’s a brutal reality to the picture which is encapsulated in its depiction of violence as sudden yet protracted, the cruelty feeling very ‘real’ despite the trappings of the fantastical that surround it. Additionally, there’s a naturalism to the depiction of the Starlight Hotel which perhaps, as has been suggested in the past, comes from Hooper’s own youth (his parents were hotel managers). Overwhelmingly, the film has an oppressive atmosphere, and it’s a bitter, nihilistic picture that is shot through with a blackly comic sensibility. In many ways, as suggested above, it bridges the two Texas Chain Saw Massacre pictures that Hooper made and reminds us that the first Texas Chain Saw Massacre is as much a black comedy as a horror picture – something which is often overlooked in discussions of the film itself, and which is foregrounded in the sequel. Like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Eaten Alive has a brutal, fast climax that ends abruptly and emphasises the cruelty of nature (both in the broader sense, and in the sense that it applies to the human animal).

This presentation of Eaten Alive easily eclipses the film’s previous home video incarnations. It’s a superb, vivid transfer of the film which is accompanied by some excellent contextual material – both old and new. Arrow’s release of Eaten Alive, it would seem, is an essential purchase for fans of Hooper and, arguably, for fans of the American horror film more generally. References: Hall, Michael, 2007: ‘Two Barmaids, Five Alligators, and the Butcher of Elmendorf’. In: Smith, Evan (ed), 2007: Texas Monthly on… Texas True Crime. University of Texas Press:133-46 Humphries, Reynold, 2002: The American Horror Film: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press Muir, John Kenneth, 2002: Eaten Alive at a Chainsaw Massacre: The Films of Tobe Hooper. North Carolina: McFarland and Company Muir, John Kenneth, 2008: Horror Films of the 1970s. North Carolina: McFarland and Company Stevens, Brad, 2003: Monte Hellman: His Life and Films. North Carolina: McFarland and Company Dark Sky DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

Dark Sky DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|