|

|

Snake of June (A) AKA Rokugatsu no hebi (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Third Window Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th September 2015). |

|

The Film

A Snake of June (Tsukamoto Shinya, 2002) A Snake of June (Tsukamoto Shinya, 2002)

Please also see our reviews of Third Window Films’ Blu-ray releases of Tsukamoto’s Bullet Ballet (1998, here) and Tokyo Fist (1995, here). Tsukamoto Shinya has been described by Mark Schilling as a ‘born filmmaker’, and from an early age Tsukamoto was making short films that were shown at festivals and on Japanese Television (Schilling, 2010: 53). Tsukamoto’s ‘breakout’ feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), was a cyberpunk fantasy which invited comparisons with the ‘body horror’ films of David Cronenberg – exploring themes of alienation, identity and the relationship between the human body and technology which would echo throughout many of Tsukamoto’s subsequent pictures. Lindsay Anne Hallam has compared Tsukamoto’s films with those of Cronenberg, arguing that both filmmakers explore a theme of ‘latent desires and feelings [that] are manifested physically on the bodies of the characters’ (Hallam, 2011: 104). Tetsuo and its sequel Tetsuo 2: Body Hammer (1992) feature characters whose ‘repressed sexual and violent desires are expressed through the fusion of flesh with metal and other technological materials’: their bodily metamorphoses are accompanied by liberation of their lustful and violent impulses (ibid.). Consequently, Hallam argues, ‘it is through the body that the cycle of transgression begins. Through the violation of the boundaries of the body, in the integration of flesh with metal, the characters are enabled to transgress against, and then destroy, all previous norms of body and society’ (ibid.). However, whereas Cronenberg’s characters in films like Shivers (1975) and Videodrome (1983) view their transformations with both ‘anxiety and disgust’, Tsukamoto’s characters experience ‘joy and delight’ (ibid.). Hallam argues that Tsukamoto’s characters can be compared with Sadean libertines: they ‘use their bodies to rebel against the prevailing culture, and rejoice in the resulting mayhem and the destruction of ordered society’ (ibid.: 105).  A Snake of June amplifies the erotic element which had always been present within Tsukamoto’s work but downplays the fetishistic depiction of the intersection between human and machine that anchors Tetsuo and its sequel. Nevertheless, the focus of A Snake of June is – as per Hallam’s analysis of Tsukamoto’s more overtly ‘cyberpunk’ pictures – on repression, its impact on the body, and the throwing off of the shackles of society. The film examines the theme of sexual repression overtly, leading at the climax of the picture to the protagonist Rinko’s (Kurosawa Asuka) exploration – not to mention public display – of her sexualty, offering a ‘rebel[lion] against the prevailing culture’ which is as potent as those found in Tsukamoto’s ‘cyberpunk’ pictures although it is presented in a less technology-driven context. Whilst A Snake of June maintains a thematic connection with Tsukamoto’s 1990s films, it moves away from the cyberpunk imagery of them and thus represents a development of Tsukamoto’s approach to these themes – which is comparable to Cronenberg’s abandonment of the more overt ‘body horror’ aspects of his earlier films during the late 1980s, with pictures such as Dead Ringers (1988), whilst retaining a focus on his abiding themes of repression and identity. A Snake of June amplifies the erotic element which had always been present within Tsukamoto’s work but downplays the fetishistic depiction of the intersection between human and machine that anchors Tetsuo and its sequel. Nevertheless, the focus of A Snake of June is – as per Hallam’s analysis of Tsukamoto’s more overtly ‘cyberpunk’ pictures – on repression, its impact on the body, and the throwing off of the shackles of society. The film examines the theme of sexual repression overtly, leading at the climax of the picture to the protagonist Rinko’s (Kurosawa Asuka) exploration – not to mention public display – of her sexualty, offering a ‘rebel[lion] against the prevailing culture’ which is as potent as those found in Tsukamoto’s ‘cyberpunk’ pictures although it is presented in a less technology-driven context. Whilst A Snake of June maintains a thematic connection with Tsukamoto’s 1990s films, it moves away from the cyberpunk imagery of them and thus represents a development of Tsukamoto’s approach to these themes – which is comparable to Cronenberg’s abandonment of the more overt ‘body horror’ aspects of his earlier films during the late 1980s, with pictures such as Dead Ringers (1988), whilst retaining a focus on his abiding themes of repression and identity.

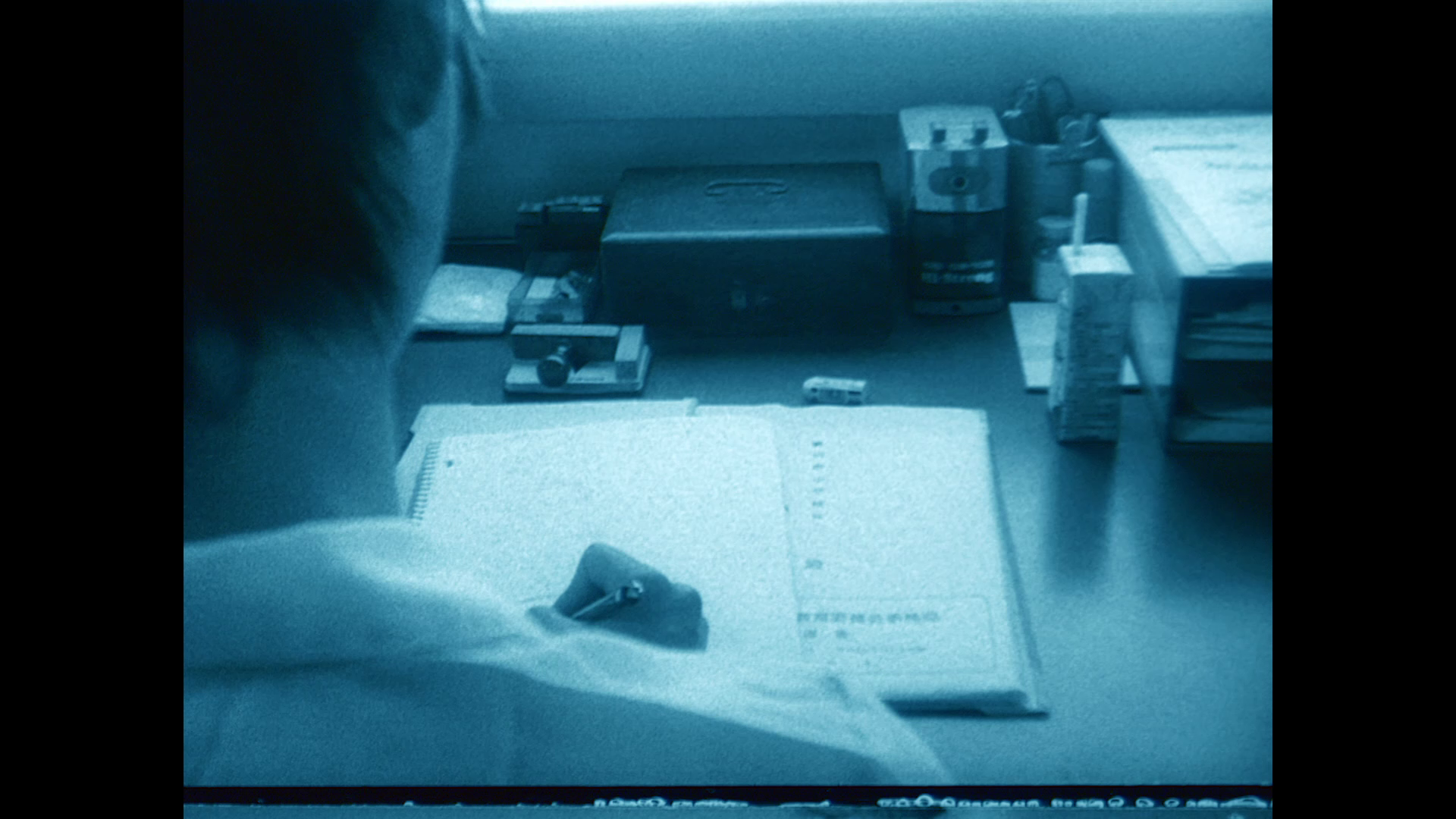

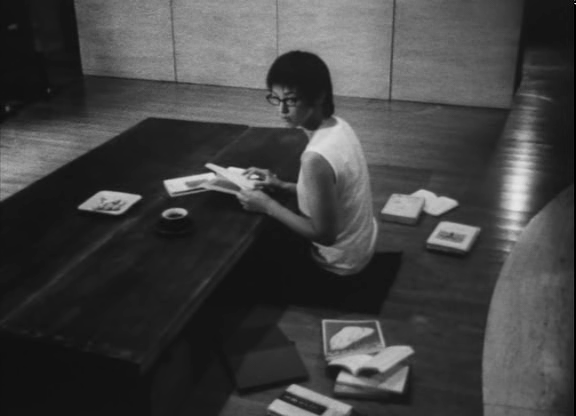

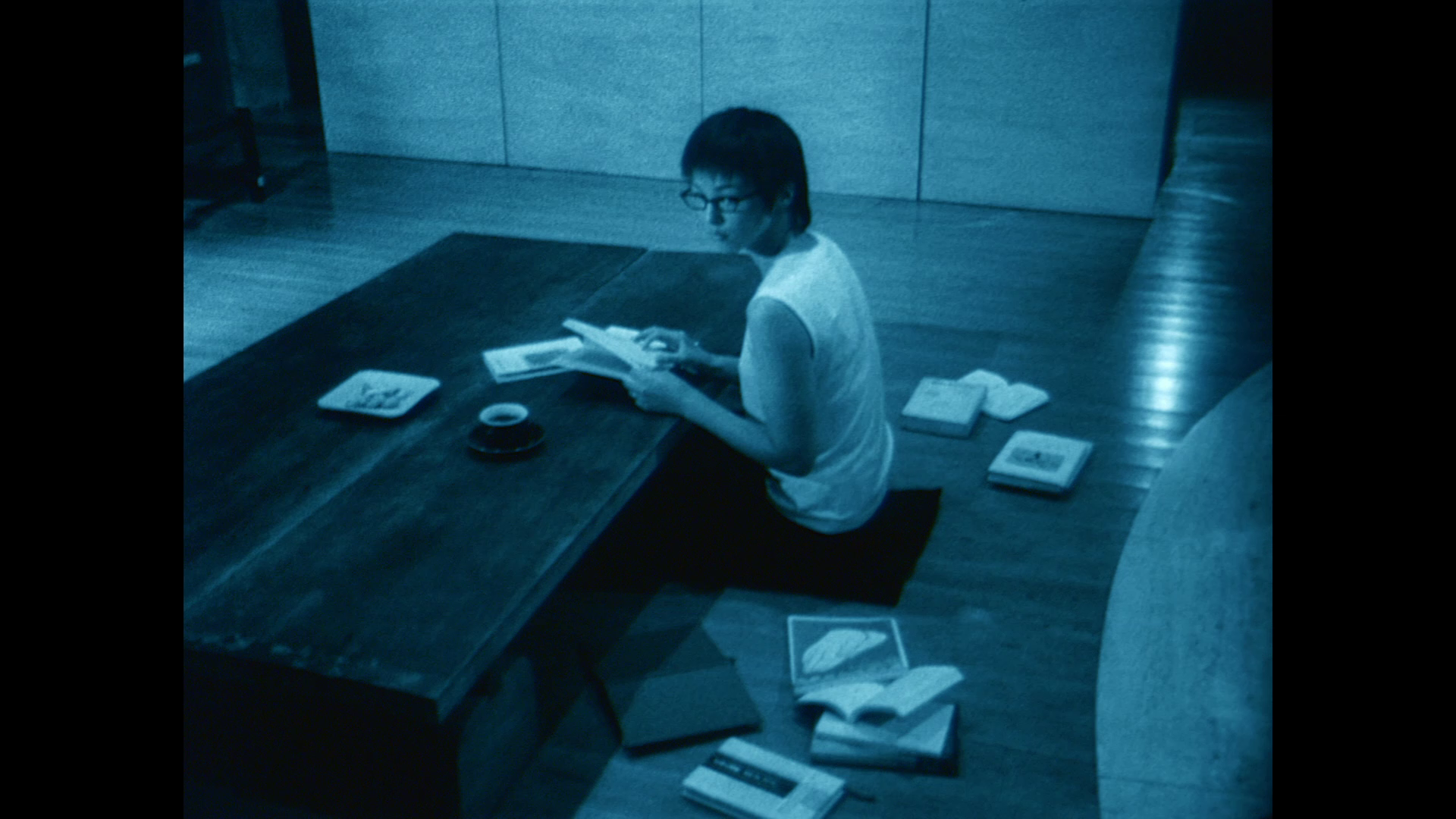

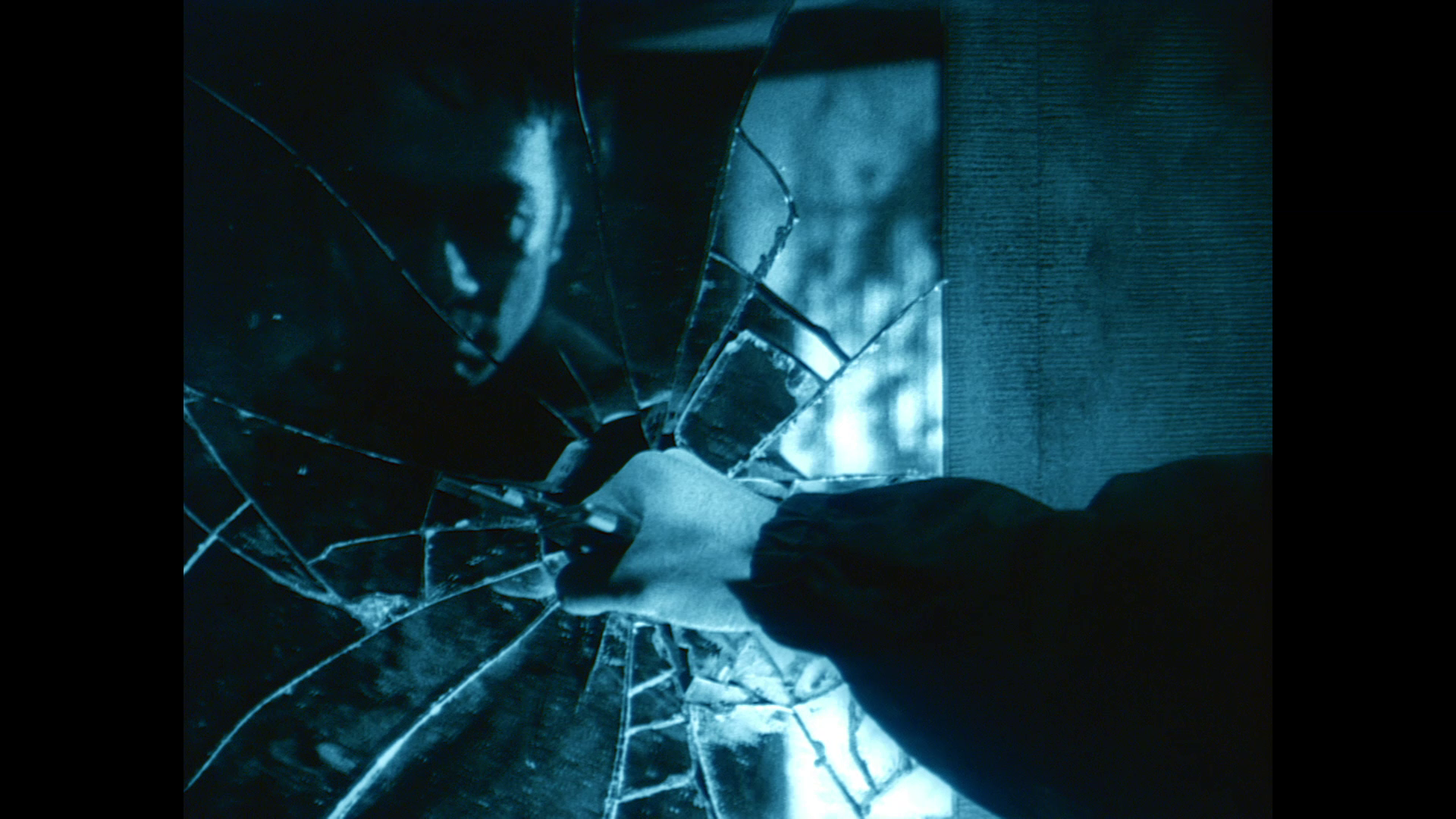

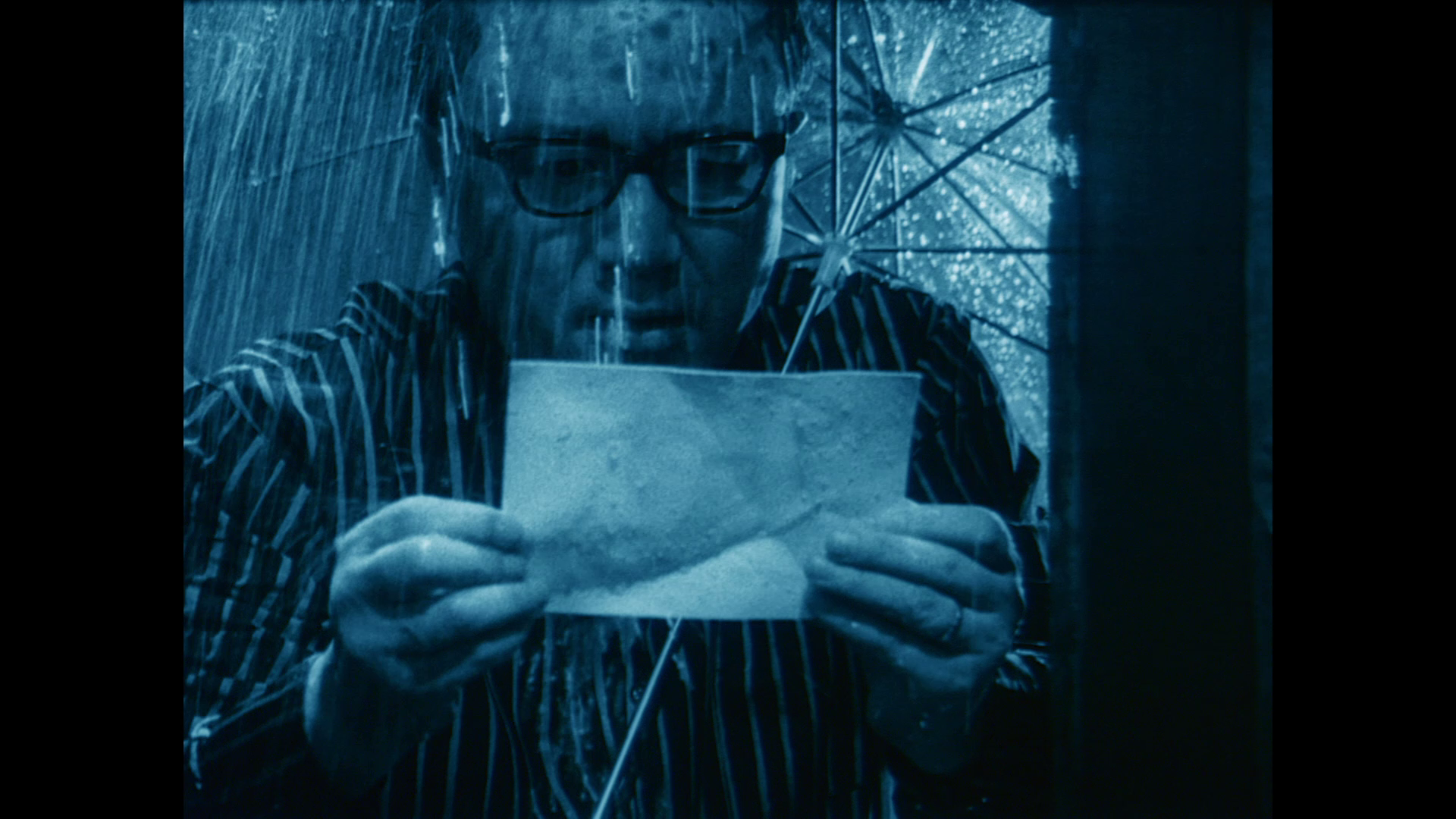

The film focuses on Rinko, a young woman who works as a counselor for a Samaritans-style suicide prevention call centre in Tokyo. Rinko is married to Shigehiko (Kotari Yuji), a middle-aged businessman who is obsessed with cleaning the family home. Rinko and Shigehiko live what seems to be a cold existence, disconnected from one another and from those around them. At work, Rinko is visited by a woman who wishes to thank Rinko for saving her son’s life; however, on their initial meeting Rinko tells her manager that she thought the woman was coming to complain about Rinko owing to the fact that Rinko had ‘been a bit tough on the boy’.  One day, Rinko receives a mysterious envelope in the mail. On the front of the envelope is written the phrase ‘Your Husband’s Secrets’, and inside the envelope are photographs of Rinko, shot with a telephoto lens, apparently masturbating. Shortly afterwards, she receives a telephone call from an unknown caller (who the audience is aware is Iguchi, played by Tsukamoto himself) who tells Rinko that he has now found a reason to live, presumably after she counseled him at her place of work. After Rinko receives another series of photographs of herself – showing her stripping in her bathroom – Iguchi calls Rinko on her private mobile telephone, asking her ‘Why don’t you do what you really want?’ Promising Rinko the negatives, Iguchi issues commands to Rinko via her mobile telephone and its connected earpiece. He tells Rinko to visit the local shopping district and, in one of the public lavatories, get changed into her miniskirt – but not to wear underwear. He orders Rinko to buy a vibrator from a sex shop and, in another public lavatory, insert it whilst leaving the device’s remote control at a public location. Using the remote control, Iguchi activates the device whilst Rinko is in public. One day, Rinko receives a mysterious envelope in the mail. On the front of the envelope is written the phrase ‘Your Husband’s Secrets’, and inside the envelope are photographs of Rinko, shot with a telephoto lens, apparently masturbating. Shortly afterwards, she receives a telephone call from an unknown caller (who the audience is aware is Iguchi, played by Tsukamoto himself) who tells Rinko that he has now found a reason to live, presumably after she counseled him at her place of work. After Rinko receives another series of photographs of herself – showing her stripping in her bathroom – Iguchi calls Rinko on her private mobile telephone, asking her ‘Why don’t you do what you really want?’ Promising Rinko the negatives, Iguchi issues commands to Rinko via her mobile telephone and its connected earpiece. He tells Rinko to visit the local shopping district and, in one of the public lavatories, get changed into her miniskirt – but not to wear underwear. He orders Rinko to buy a vibrator from a sex shop and, in another public lavatory, insert it whilst leaving the device’s remote control at a public location. Using the remote control, Iguchi activates the device whilst Rinko is in public.

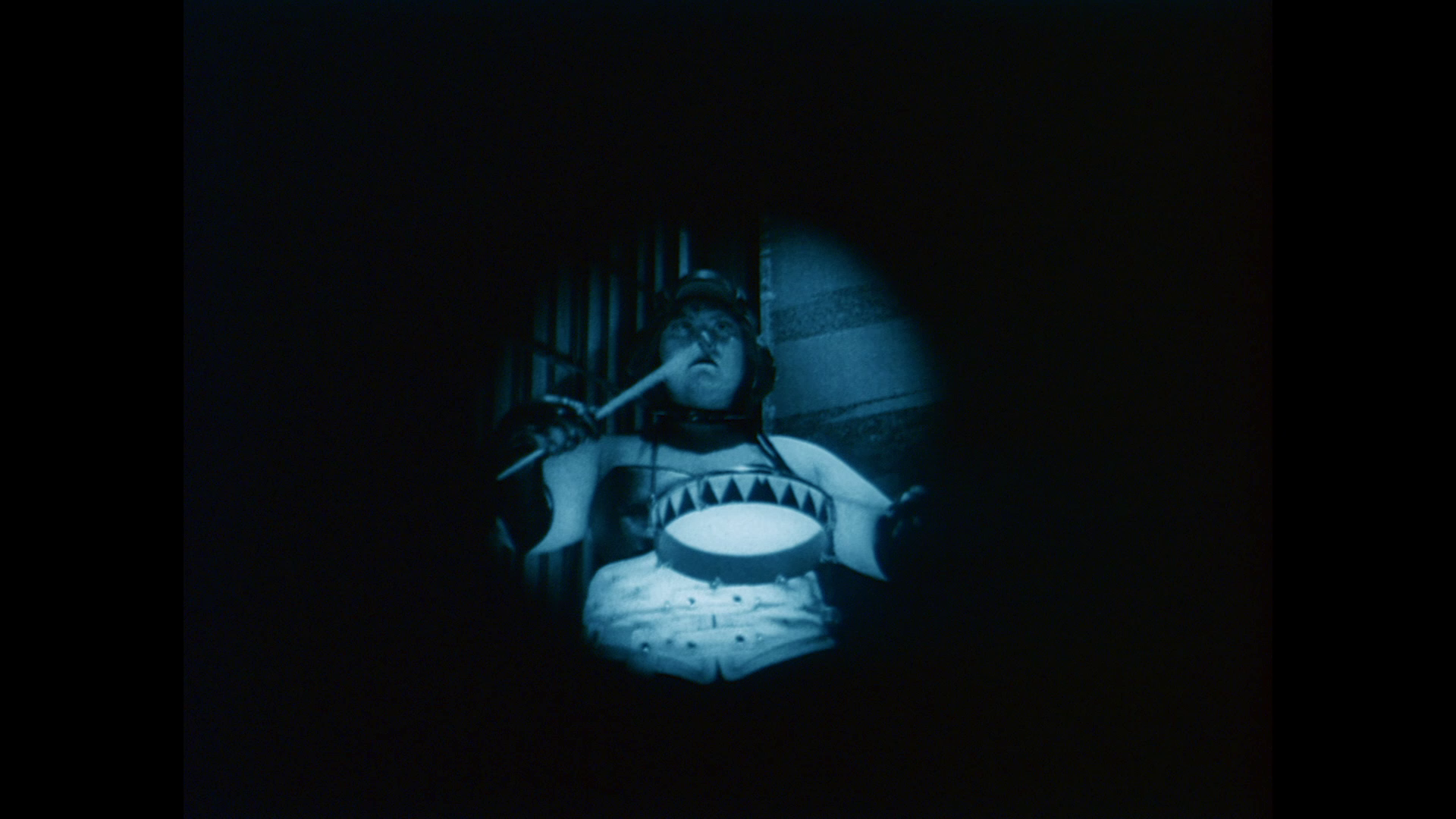

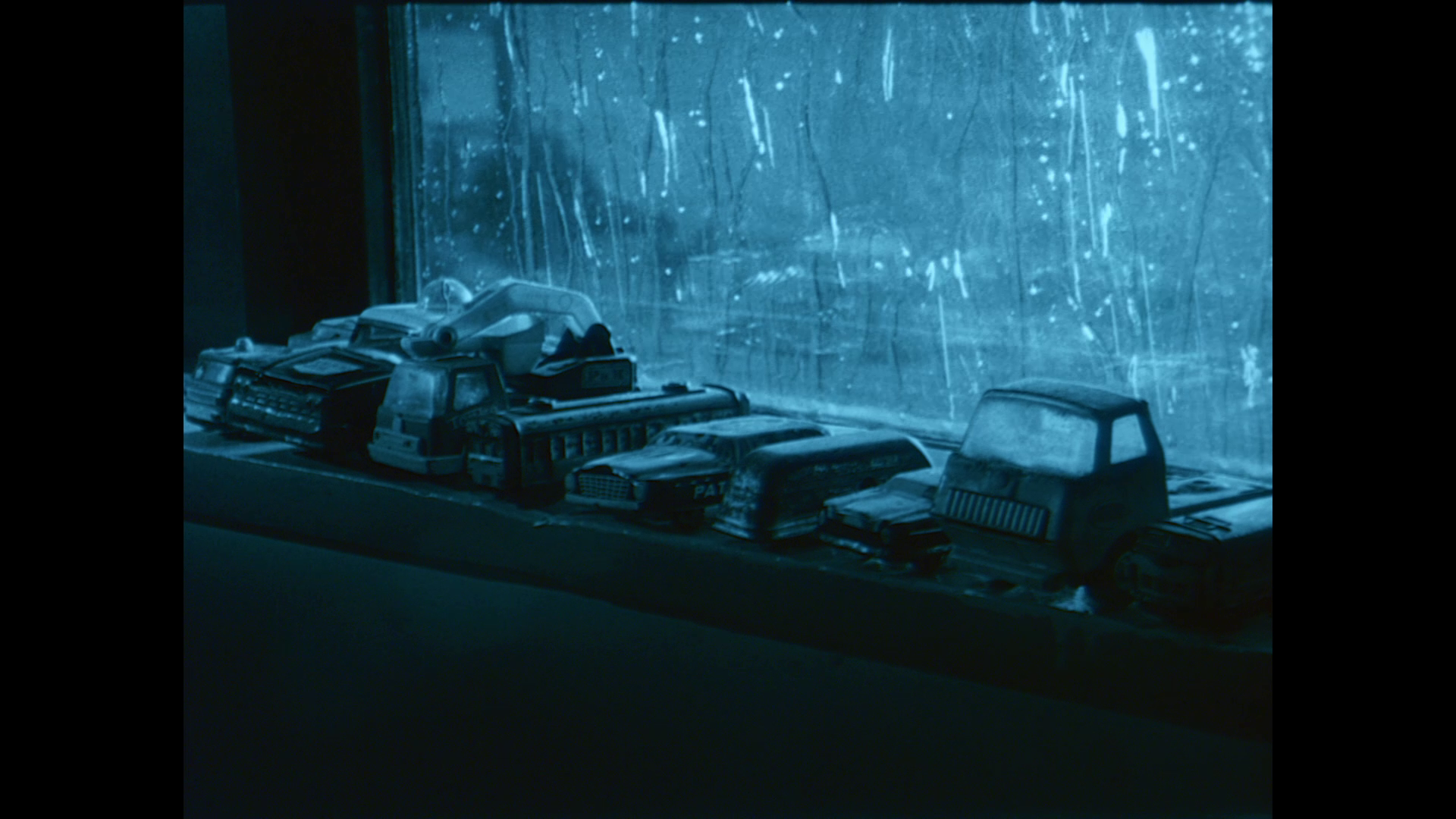

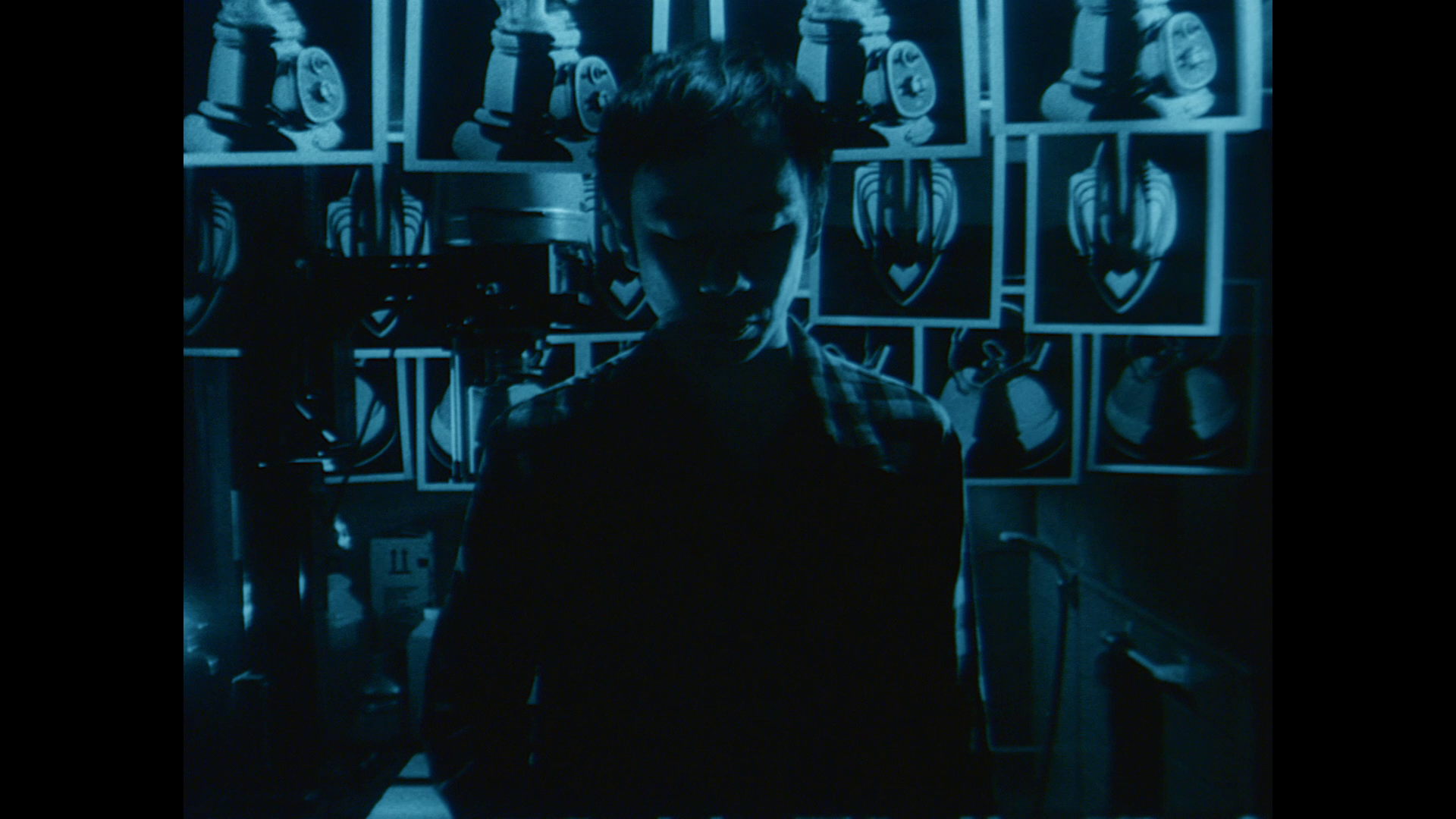

In the days following, Iguchi continues to taunt Rinko and suggests that in one of the photographs he took of her, he has seen evidence that Rinko may have breast cancer – and that she should seek to undergo a mastectomy. Iguchi soon begins to telephone Shigehiko and taunt him too. In a café, Iguchi slips a mickey into Shigehiko’s drinking water, and when he awakens Shigehiko experiences a strange vision which includes a funnel strapped to his face through which he views two women being sexually assaulted and drowned in a large water tank. One day, at the shopping district Shigehiko sees his wife dressed in her short miniskirt and follows her. Rinko is now transformed into a confident woman, unafraid of her sexuality and more than willing to exhibit it. Shigehiko follows Rinko to a deserted parking lot where Iguchi waits in a car with his camera. As Shigehiko strips naked in the rain-soaked parking lot, Iguchi photographs her. Shigehiko, now himself transformed into a voyeur, watches from a distance and masturbates. Later, Shigehiko makes contact with Iguchi and tries to buy the photographs and negatives from the impromptu photo shoot, and Iguchi lures Shigehiko to a seemingly derelict building where Iguchi assaults Shigehiko, attacking the salaryman with a bizarre, phallic metal appendage which grows out of Iguchi’s stomach.  Initially at least, the film seems like a deviation from the cyberpunk scenarios of Tsukamoto’s earlier films, including the Tetsuo pictures and Tokyo Fist. However, as the narrative of Snake of June develops, the picture’s similarities with Tsukamoto’s previous films becomes increasingly apparent. This is most obvious in the bizarre scenario in which Iguchi drugs Shigehiko and Shigehiko experiences a jarring fantasy-or-maybe-not sequence: he awakens with an unusual funnel mask on his face (clearly intended to symbolise his transformation into Iguchi’s own brand of voyeurism) and the film’s audience is treated to point-of-view shots from Shigehiko’s perspective which, complete with an iris-type effect, depict the apparent rape of two women followed by their drowning in a specially-constructed tank. Following this, Iguchi attacks Shigehiko with the aid of steel toe-capped boots and a lengthy, phallic metal appendage which snakes out of Iguchi’s stomach to wrap itself around Shigehiko’s throat. Like Bullet Ballet and Tokyo Fist in particular, Snake of June also depicts the urban environment as utterly barren and characterised by isolation – even within the family home. Initially at least, the film seems like a deviation from the cyberpunk scenarios of Tsukamoto’s earlier films, including the Tetsuo pictures and Tokyo Fist. However, as the narrative of Snake of June develops, the picture’s similarities with Tsukamoto’s previous films becomes increasingly apparent. This is most obvious in the bizarre scenario in which Iguchi drugs Shigehiko and Shigehiko experiences a jarring fantasy-or-maybe-not sequence: he awakens with an unusual funnel mask on his face (clearly intended to symbolise his transformation into Iguchi’s own brand of voyeurism) and the film’s audience is treated to point-of-view shots from Shigehiko’s perspective which, complete with an iris-type effect, depict the apparent rape of two women followed by their drowning in a specially-constructed tank. Following this, Iguchi attacks Shigehiko with the aid of steel toe-capped boots and a lengthy, phallic metal appendage which snakes out of Iguchi’s stomach to wrap itself around Shigehiko’s throat. Like Bullet Ballet and Tokyo Fist in particular, Snake of June also depicts the urban environment as utterly barren and characterised by isolation – even within the family home.

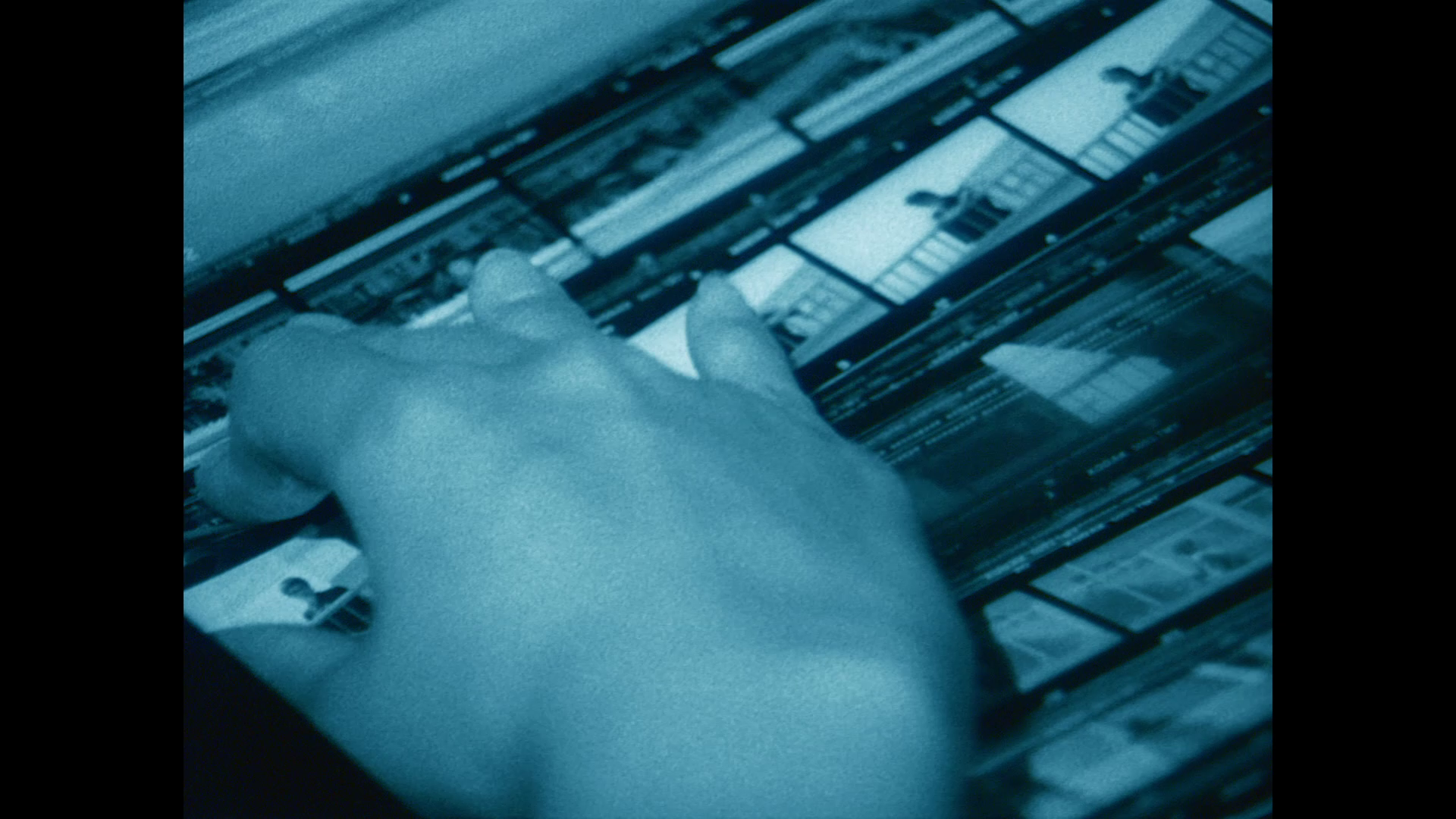

As in Tsukamoto’s earlier films, the characters in A Snake of June are isolated and alienated within the urban environment. Returning home on the train, Rinko is shown standing in a tightly-packed carriage, face to face with a man. She slaps the man suddenly – her gesture suggesting that Rinko has been made the victim of the well-documented Japanese problem of chikan (unwanted groping on crowded trains). Rinko and Shigehiko’s homelife is similarly characterised by isolation: the couple sleep separately and live separate lives, Shigehiko’s private time dominated by his obsessive need to scour the kitchen and bathroom sinks – the image of the water draining out of these via their circular plugholes offering yet another variation on the film’s central visual motif of water falling from the sky, running along man-made surfaces and across the bodies of the characters, and flowing into drains.  From its opening moments, A Snake of June foregrounds the practice of photography and connects it with voyeurism and sexual penetration. The film begins with fragmented close-ups of a Nikon 35mm SLR – the flash bulb, the front element of the camera’s lens – which fragments and fetishises the instrument of photography in much the same way that women’s bodies are usually fragmented and fetishised/commodified by the camera (see Rammurthy, 2015: 263). In this instance, for the first of several times in the film, Iguchi’s camera is itself turned upon the audience, returning the gaze of the viewer and thereby destabilising our point of view. From here, we are presented with shots of a woman, the photographer’s (Iguchi’s) subject. On the soundtrack, we hear a female voice (presumably that of Iguchi’s model) speaking, telling us that ‘A small camera won’t do. Has to be the big one with a flash’. As she says these words, her voice overlaps with a male voice (that of Iguchi) which repeats her words, adding the phrase: ‘Otherwise, you can’t make her come’. The connection between photography and sex is thus established, with the camera functioning (in Iguchi’s worldview at least) as a sexual tool – a substitute for the penis. With this, we are presented with shots depicting Iguchi’s model stripping, strobe cuts intended to indicate the firing of the flash attached to Iguchi’s SLR. Likewise, towards the end of the film Iguchi photographs the now-sexually confident Rinko in the deserted parking lot. Rinko strips for Iguchi’s camera, and he’s separated from her, the distance between photographer and subject underscored by the fact that Iguchi is pointing his camera at Rinko from the interior of a car; the distance between the pair is emphasised by the fact that they are not shown in the frame together. From its opening moments, A Snake of June foregrounds the practice of photography and connects it with voyeurism and sexual penetration. The film begins with fragmented close-ups of a Nikon 35mm SLR – the flash bulb, the front element of the camera’s lens – which fragments and fetishises the instrument of photography in much the same way that women’s bodies are usually fragmented and fetishised/commodified by the camera (see Rammurthy, 2015: 263). In this instance, for the first of several times in the film, Iguchi’s camera is itself turned upon the audience, returning the gaze of the viewer and thereby destabilising our point of view. From here, we are presented with shots of a woman, the photographer’s (Iguchi’s) subject. On the soundtrack, we hear a female voice (presumably that of Iguchi’s model) speaking, telling us that ‘A small camera won’t do. Has to be the big one with a flash’. As she says these words, her voice overlaps with a male voice (that of Iguchi) which repeats her words, adding the phrase: ‘Otherwise, you can’t make her come’. The connection between photography and sex is thus established, with the camera functioning (in Iguchi’s worldview at least) as a sexual tool – a substitute for the penis. With this, we are presented with shots depicting Iguchi’s model stripping, strobe cuts intended to indicate the firing of the flash attached to Iguchi’s SLR. Likewise, towards the end of the film Iguchi photographs the now-sexually confident Rinko in the deserted parking lot. Rinko strips for Iguchi’s camera, and he’s separated from her, the distance between photographer and subject underscored by the fact that Iguchi is pointing his camera at Rinko from the interior of a car; the distance between the pair is emphasised by the fact that they are not shown in the frame together.

Iguchi’s motives for goading Rinko into committing acts of exhibitionism and – at least initially – humiliating public displays of sexuality are mysterious, though Iguchi claims that as Rinko ‘made me want to live’ he wishes to push her towards throwing off the shackles of repression that have led to her seemingly barren existence. ‘I’m not asking you for sex’, Iguchi tells Rinko during one of their telephone conversations, ‘I’m telling you to do what you want’. Later, after Rinko has complied with Iguchi’s demands he asks her, ‘Tell me what made you become so daring at this rainy season of the year. Something has burst open in you [….] Don’t worry how people react. Show them who you are’. Shortly afterwards, Iguchi insists that Rinko ‘told me on the phone at the centre, “You have to do what you really want to”’, and it was this advice that saved his life – and which he is returning to Rinko. Iguchi believes that the cancer he perceives within Rinko has been caused directly by her sexual repression: ‘Nuns tend to suffer from breast cancer because they repress their bodily desires’, he suggests towards the end of the film. With Iguchi’s ‘coaching’, Rinko gradually undergoes a metamorphosis, from a repressed, mousy housewife into a vibrantly sexual being. When Iguchi first goads Rinko into visiting the shopping district and parading around in her miniskirt sans underwear, Rinko is embarrassed and anxious. Later in the film, when Shigehiko sees Rinko in her miniskirt in the same scenario her body language suggests she is confident, and we see her masturbating in the public lavatories, apparently thrilled at her escapades. Her transformation is completed by the mastectomy she undergoes, which within the film is framed almost as an example of body modification. Shigehiko initially resists Rinko’s desire to undergo the mastectomy, but at the end of the film, as their marital relationship has been re-established, Rinko returns to her husband and removes her clothing to reveal that one of her breasts has been removed surgically. Shigehiko kisses the flesh where her breast once was, suggesting an eroticisation of the transformed body – a transformation enabled by science and technology that connects A Snake of June overtly with the theme of bodily modification to be found in Tsukamoto’s earlier pictures.    The film is here presented uncut, with a running time of 76:54 mins.

Video

The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.33:1. (Tsukamoto reputedly experimented with shooting the film in the 1:1 ratio associated with medium format still cameras, presumably in response to the work of still photographers like Bruce Weber and Helmut Newton which inspired the aesthetic of the film. However, this plan was soon abandoned when it proved difficult to achieve.) The 1080p presentation takes up approximately 13Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.33:1. (Tsukamoto reputedly experimented with shooting the film in the 1:1 ratio associated with medium format still cameras, presumably in response to the work of still photographers like Bruce Weber and Helmut Newton which inspired the aesthetic of the film. However, this plan was soon abandoned when it proved difficult to achieve.) The 1080p presentation takes up approximately 13Gb of space on a single-layered Blu-ray disc.

The film has a very distinctive aesthetic: A Snake of June was shot on 16mm monochrome film and then printed on 35mm colour stock both to give it the steely blue tint that Tsukamoto wanted, and also to retain the sharpness of the image whilst minimising the more aggressive grain structure that, associate producer Kawahara Shinichi argues in the extras on this disc, would have resulted from printing the film on 35mm monochrome stock. (As a point of contrast, Tsukamoto’s Bullet Ballet had been shot on 16mm monochrome stock but then blown up and printed on 35mm monochrome stock, resulting in that film having a more grain-heavy appearance.) This new digital restoration of the film offers a very strong presentation of the picture, with an impressive level of detail which is particularly evident in close-ups and good contrast levels throughout. The mid-tones are strong and there are deep, rich blacks which can sometimes appear slightly ‘crushed’ – but this is a characteristic of the original photography, which is dominated by low-light sequences. The photography within the film, stressing the isolation and misery of the characters visually, is dark and dingy throughout, and this new restoration captures that perfectly. It’s a lovely, balanced image. Strangely, at each edit point within the film there’s something that looks like analogue tape damage (warp lines) at the top and bottom of the frame. These only appear for a fraction of a second, but they’re present at every edit point and, to the best of my recollection, weren’t evident in any of the other presentations of the film that I’ve seen (one of the US DVDs, sans the blue tint, and the DVD released by Tartan in the UK). Below are a couple of large images to demonstrate their appearance. I have no detailed explanation for them at present, but though they appear throughout the film they’re not too distracting and certainly don’t detract from the self-evident strengths of this presentation. (EDIT: Thanks to Per-Olof Strandberg, who confirmed my suspicion that these were simply evidence of the editing process through which the shot-on-16mm film passed by contacting us to say that 'These are the glue marks from 16mm negative, that is usually edited in A + B stripes. Every second scene is in A, and every second in B. The empty space in A and B are black film. 16 mm negative is so thin that the glue is visible. Projected in cinemas at 1:1.37, the top and bottom are not seen as in the Blu-ray. The same marks are also in the UK DVD. Usually the glue also causes the image to jump in the cut. It's similar in other 16mm films, like Leaving Las Vegas, etc'.)

NB. At the bottom of this review are some larger screen grabs, including some comparison grabs with one of the black-and-white DVD presentations released in the US.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. This is rich in range and far from ‘showy’ but comes alive with the use of ambient sounds (eg, the persistent rain) which fill the soundscape. This is accompanied by optional English subtitles which are clear, easy to read and grammatically correct.

Extras

Extras include:  - an audio commentary with critic Tom Mes. Mes discusses the film in detail, examining its meanings and its relationship with Tsukamoto’s other pictures. He suggests that the picture is an ‘erotic film’ but is ‘not in any sense an exploitative film’ and may be regarded as ‘a feminist film, in a way’. It’s a detailed, thoughtful track that evidences Mes’ familiarity with Tsukamoto’s films and demonstrates a rich, critical approach to the film. - an audio commentary with critic Tom Mes. Mes discusses the film in detail, examining its meanings and its relationship with Tsukamoto’s other pictures. He suggests that the picture is an ‘erotic film’ but is ‘not in any sense an exploitative film’ and may be regarded as ‘a feminist film, in a way’. It’s a detailed, thoughtful track that evidences Mes’ familiarity with Tsukamoto’s films and demonstrates a rich, critical approach to the film.

- Interview with Director Shinya Tsukamoto (25:41). In this new interview, Tsukamoto discusses the origins of the film and his intentions in making it, the ‘meaning’ of the film’s title, and the film’s fusion of aspects of the erotic film and the thriller. Tsukamoto also discusses his appearance in the film as Iguchi, and reflects on the ways in which the reception of the film in the West differed from its reception in Japan. He discusses the photography within the picture, talking at some length about the technique used to achieve the blue tint – and reminds the viewer that monochrome photography is colour photography, and that black and white are both colours. (It’s nice to hear Tsukamoto discuss this, as it’s something that’s often forgotten in discourse about both photography and film – with monochrome photography often being placed in a reductive dualism with ‘colour’ photography). Tsukamoto says the use of monochrome in the film was influenced by the nude photography of Bruce Weber and Helmut Newton. Tsukamoto is also asked about his choice to use 16mm film and present the picture in the old Academy ratio. - ‘Shooting A Snake of June’ (19:48). In this featurette, which has been included on some of the film’s previous DVD releases, Tsukamoto discusses his long-standing desire to make this picture and suggests that the overriding theme of his work is the relationship between the city and its human inhabitants. Snake of June ‘is sort of the ultimate extension of that theme’. Tsukamoto had a distinctive visual style, ‘acidic black and white’, in mind because ‘black and white photography has its own kind of sensuality or eroticism’. The film was shot on 16mm monochrome film and then blown up to 35mm colour stock in an attempt to, in the works of associate producer Kawahara Shinichi, retain the ‘sharp image quality’ whilst reducing the ‘grainy look’ of Bullet Ballet (which was shot in monochrome on 16mm stock and blown up to 35mm monochrome stock). The production ‘took advantage’ of printing on colour film to ‘give the film a blue tinge suggesting water’. The finished product, Tsukamoto says, ‘looked like a black and white picture stained blue, and that look gave the impression of a concrete-covered city’. Tsukamoto also talks about his initial desire to shoot the film in a 1:1 format. Experiements were made by the film’s chief photography assistant Shida Takayuki to modify the Canon Scoopic camera used to shoot the picture, but these resulted in the camera being unable to focus properly. So with only a week to go before shooting began, Tsukamoto instead chose to shoot the film in 1.37:1. He reflects that the initial desire to shoot the picture in 1:1 was perhaps ‘too showy’. The film’s heavy use of rain effects is also discussed, with the problem of backlighting the rain in order to make it visible on screen. The significance of careful production design on Tsukamoto’s films is examined too – as is circles and their association with ‘natural, organic things’. The featurette features input from Tsukamoto alongside associate producer Kawahara Shinichi, colour timing technician Oomi Masaharu, chief photography assistant Shida Takayuki, special effects technician Nakamura Hajime and sound designer Kitada Masaya. A series of trailers are also included: - The UK trailer for the film (2:24). - The trailer for Tetsuo 1 and Tetsuo 2 (1:58). - The trailer for Tokyo Fist (2:29). - The trailer for Bullet Ballet (2:23). - The trailer for Kotoko (1:59).

Overall

A Snake of June is a fascinating film that lingers in the memory. It’s a picture which on its surface and at the time of its initial release seemed to break away from some of the preoccupations of Tsukamoto’s earlier films, but on reflection it simply consolidates some of the themes of those films but presents them in a slightly different – arguably less didactic – manner. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is very good and sure to please the film’s fans, and the film itself is accompanied by some excellent contextual material – including the new interview with Tsukamoto and Tom Mes’ commentary. References: Hallam, Lindsay Anne, 2011: Screening the Marquis the Sade: Pleasure, Pain and the Transgressive Body in Film. London: McFarland Rammurthy, Anandi, 2015: ‘Spectacles and illusions: photography and commodity culture’. In: Wells, Liz (ed), 2015: Photography: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge: 231-88 Schilling, Mark, 2010: ‘Tokyo Fist (capsule review)’. In: Berra, John (ed), 2010: Directory of World Cinema: Japan. London: Intellect Books: 53-4 Comparison with one of the US DVD releases, which presented the film sans the blue tint: US DVD:

Third Window Films’ Blu-ray:

US DVD:

Third Window Films’ Blu-ray:

US DVD:

Third Window Films’ Blu-ray:

US DVD:

Third Window Films’ Blu-ray:

More grabs from Third Window Films’ Blu-ray presentation:

|

|||||

|