|

|

Happiest Days of Your Life (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Studio Canal Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th October 2015). |

|

The Film

The Happiest Days of Your Life (Frank Launder, 1950) The Happiest Days of Your Life (Frank Launder, 1950)

Adapted from John Dighton’s 1948 stage farce of the same title, Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat’s The Happiest Days of Your Life (1950) sits comfortably within a long line of British comedy films focusing on the educational system. This group of films includes the Will Hay picture Boys Will Be Boys (William Beaudine, 1935) and continued through The Happiest Days of Your Life to the film adaptations of Ronald Searle’s St Trinian’s cartoons (beginning with Frank Launder’s The Belles of St Trinian’s in 1954) and Carry on Teacher (Gerald Thomas, 1959). The Happiest Days of Your Life begins as Richard Tassell (John Bentley), the new English master, arrives at Nutbourne College – a boys’ school. ‘You’re going to loathe it here, you know’, Tassell is told by Billings, the maths teacher (Richard Wattis). Tassell is soon introduced to other members of the school’s staff: Ramsden (Arthur Howard), the science teacher; Victor Hyde-Brown (Guy Middleton), aka Whizzo, the sports master; Monsieur Joue (Percy Walsh), the French teacher; and Wetherby Pond (Alistair Sim), the headmaster. Pond, it seems, has been considered for a loftier position: the headmastership of Harlingham. (‘But that’s a decent school! One of the majors!’, Hyde-Brown protests when Pond reveals this to his colleagues.) Pond is desperate to impress the governors of Harlingham, who are due to visit Nutbourne in order to observe the school and assess Pond’s suitability for the headmastership at their prestigious institution.  Amidst this, Nutbourne’s staff discover that the luggage of a hundred more students than expected has been delivered to the school. At first, they believe an administrative mix-up is the cause of this, but soon they realise that another school is to share the premises. As if the stress on the amount of space within the school isn’t a big enough issue, Pond and his colleagues discover that the school that is scheduled to move into Nutbourne College is St Swithin’s – a girls’ school. The male teachers of Nutbourne College share their distrust of their female counterparts: ‘There are only two types of schoolmistress, chum’, Billings tells Tassell, ‘The battleaxe or the Amazon. And I bet you five bob they [the teachers of St Swithin’s] fall into one class or another’. Amidst this, Nutbourne’s staff discover that the luggage of a hundred more students than expected has been delivered to the school. At first, they believe an administrative mix-up is the cause of this, but soon they realise that another school is to share the premises. As if the stress on the amount of space within the school isn’t a big enough issue, Pond and his colleagues discover that the school that is scheduled to move into Nutbourne College is St Swithin’s – a girls’ school. The male teachers of Nutbourne College share their distrust of their female counterparts: ‘There are only two types of schoolmistress, chum’, Billings tells Tassell, ‘The battleaxe or the Amazon. And I bet you five bob they [the teachers of St Swithin’s] fall into one class or another’.

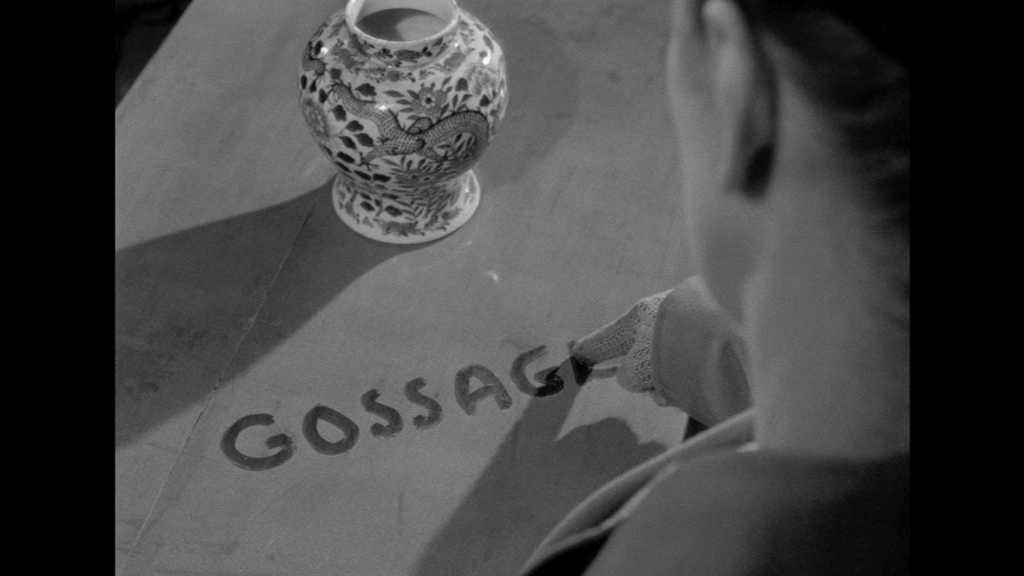

The headteacher of St Swithin’s, Miss Whitchurch (Margaret Rutherford), is as disturbed as Pond to discover that her students are to mix with the opposite sex. Amongst the staff of St Swithin’s are Miss Gossage (Joyce Grenfell), Miss Jezzard (Muriel Aked), Miss Chapel (Myrette Morven) and Miss Harper (Bernadette O’Farrell) – the latter of whom quickly becomes the object of goo-goo eyes made by the staff of Nutbourne College. The arrival of St Swithin’s girls soon results in the departure of the kitchen staff of Nutbourne College – who are alienated by the pressure that is placed on them to cater for the much larger group of students on the premises. In their place, the girls of St Swithin’s cook for the school, with less than pleasing results. Things become even more complicated when the parents of some of the girls arrive on the premises at the same time as the governors of Harlingham – and Whitchurch must escort the parents around the premises at the same time as Pond must escort the governors of Harlingham around the school, with both parties enacting a complicated charade to keep from the respective parties the revelation that boys and girls are sharing the same grounds.  In British Film, Jim Leach suggests that British films about school settings can be divided into ‘serious’ pictures that ‘descend from Tom Brown’s Schooldays’ and ‘comic treatments of school life’ which ‘have their roots in Jean Vigo’s Zéro de conduite (1933)’ (Leach, 2004: 188). Leach suggests that Vigo’s film may have been a particular influence on The Happiest Days of Your Life, which features an opening sequence that ‘visually recalls the opening of the French film’ and an ‘anarchic spirit’ which is close to that achieved in Zéro de conduite. In British Film, Jim Leach suggests that British films about school settings can be divided into ‘serious’ pictures that ‘descend from Tom Brown’s Schooldays’ and ‘comic treatments of school life’ which ‘have their roots in Jean Vigo’s Zéro de conduite (1933)’ (Leach, 2004: 188). Leach suggests that Vigo’s film may have been a particular influence on The Happiest Days of Your Life, which features an opening sequence that ‘visually recalls the opening of the French film’ and an ‘anarchic spirit’ which is close to that achieved in Zéro de conduite.

The film is set in the years following the war, ‘when buildings were in short supply and therefore, conceivably, a civil servant could accidentally re-house two boarding schools onto the same premises’ (Simpson, 2008: 99). As Mark Simpson argues, the ‘fact that they [the two schools forced to share the same premises] were opposite sex schools was, in post war Britain, all the more epicurean, since it tapped into a sensitive vein within the British psyche’ (ibid.: 99-100). The site of this farce, Nutbourne College is a place of history: ‘Fine old staircase’, Billings tells Tassell with regards the flight of stairs in the school’s entrance hallway, ‘unless you have to climb it twenty times a day’. As the film begins, the institution seems to be in financial dire straits: ‘According to history, it [the school] goes back to Henry VIII’, Billings declares, ‘According to the bank, it goes back to them unless Pond keeps up with his payments’. Under Pond’s leadership, the school seems to place great emphasis on putting on a show for the parents: again during Tassell’s tour of the school, Billings tells him ‘This place hasn’t had a coat of paint since they took photographs for the prospectus’. When the teachers of Nutbourne discover that another school is to share Nutbourne College’s grounds, before they realise that this other school is a girls’ school, Billings suggests sleeping the children ‘two in a bed, end to end’. ‘We have the parents to consider, Billings’, Pond reminds him, ‘We must appear to give them value for money’. Upon seeing John Dighton’s stage play, Frank Launder reputedly immediately saw the farce as offering a chance to develop a comedy film that would rival those produced by Ealing Studios. The film makes explicit the ‘much-noted suppression of sexuality’ that was ‘an implicit’ feature of many of the Ealing comedies: in The Happiest Days of Your Life, this suppression of sexuality is ‘at the centre of the narrative, where two comic monsters, elderly celibates, not only attempt to perpetuate a system of education […] based on class and sex division into totally separate spears, but also to discourage any signs of sexuality in their charges’ (Babington, 2002: 153).  In his book about Launder and Gilliat, Bruce Babington discusses the ‘resolute oldfashionedness of Sim’s and Rutherford’s personae’ in The Happiest Days of Your Life (Babington, op cit.: 159). Both Pond and Whitchurch express extreme concerns about the mixing of the sexes. (Early in the film, Billings tells Tassell, ‘The day Pond exchanges a smile with a woman, I’ll dance the hornpipe naked in the village green’.) Within this context, the grand irony at the end of the picture is that the man from the Ministry of Education arrives and declares that the school is a ‘co-educational school’ before heralding the arrival of an even worse terror (at least within the paradigms presented by Pond and Whitchurch) than the idea of a mixed sex private school: a rabble of working class children from a co-ed state school. Where Pond and Whitchurch differ on the relative merit of the two sexes, they agree on the principle that ‘never the twain shall meet’ (ibid.: 162). Whitchurch’s ‘feminism’, Babington notes, ‘is of a particular late-nineteenth-century kind, predicated on the notion of the superiority of the female, introjecting the highest of patriarchal culture (her school is named for a male saint and all the houses after male poets […]) but with absolutely no interesting the merging of male and female worlds’ (ibid.). Ironically, though, the model of education that Whitchurch provides is about preparing girls to be ‘good’ wives (ibid.). When Nutbourne’s kitchen staff depart, Whitchurch enlists her girls in preparing meals for the two schools, resulting in a wonderful sequence that pokes fun at David Lean’s 1948 adaptation of Oliver Twist, in which one of the boys of Nutbourne declares, in the dining hall, ‘Please, sir. I don’t want any more. No, sir’. Shortly afterwards, Billings discovers a parcel sent home by one of the boys: it contains a fishcake made by the girls of St Swithin’s, addressed to the boy’s father, an analytical chemist, with the message, ‘Dear Dad. Our breakfast. Get weaving. Reg’. In his book about Launder and Gilliat, Bruce Babington discusses the ‘resolute oldfashionedness of Sim’s and Rutherford’s personae’ in The Happiest Days of Your Life (Babington, op cit.: 159). Both Pond and Whitchurch express extreme concerns about the mixing of the sexes. (Early in the film, Billings tells Tassell, ‘The day Pond exchanges a smile with a woman, I’ll dance the hornpipe naked in the village green’.) Within this context, the grand irony at the end of the picture is that the man from the Ministry of Education arrives and declares that the school is a ‘co-educational school’ before heralding the arrival of an even worse terror (at least within the paradigms presented by Pond and Whitchurch) than the idea of a mixed sex private school: a rabble of working class children from a co-ed state school. Where Pond and Whitchurch differ on the relative merit of the two sexes, they agree on the principle that ‘never the twain shall meet’ (ibid.: 162). Whitchurch’s ‘feminism’, Babington notes, ‘is of a particular late-nineteenth-century kind, predicated on the notion of the superiority of the female, introjecting the highest of patriarchal culture (her school is named for a male saint and all the houses after male poets […]) but with absolutely no interesting the merging of male and female worlds’ (ibid.). Ironically, though, the model of education that Whitchurch provides is about preparing girls to be ‘good’ wives (ibid.). When Nutbourne’s kitchen staff depart, Whitchurch enlists her girls in preparing meals for the two schools, resulting in a wonderful sequence that pokes fun at David Lean’s 1948 adaptation of Oliver Twist, in which one of the boys of Nutbourne declares, in the dining hall, ‘Please, sir. I don’t want any more. No, sir’. Shortly afterwards, Billings discovers a parcel sent home by one of the boys: it contains a fishcake made by the girls of St Swithin’s, addressed to the boy’s father, an analytical chemist, with the message, ‘Dear Dad. Our breakfast. Get weaving. Reg’.

Within this framework, Pond’s quoting of John Knox (‘The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women’, in which Knox declares that ‘it is more than a monster in nature that a woman should reign and have empire above man’) at the opening of one of his classes – soon disrupted by the arrival of Whitchurch and St Swithin’s schoolgirls – invests Knox’s assertion with a double/stratified meaning. The quote, which in its original context (1558) referred to the reign of the Catholic monarch Mary Tudor and her persecution of Protestants, is here used to ‘evoke World War II and the “mobile women” of Launder and Gilliat’s home front trilogy, as well as films like The Gentle Sex, Perfect Strangers and Colonel Blimp where women are seen prominently in uniform’ (Babington, op cit.: 163).  The film obliquely references the pre-war period as an era of stability, suggesting that the root of the order that befalls both Nutbourne and St Swithin’s is the administrative and social fallout from the Second World War. There are some wonderful gags within the film about nationalisation and post-war reorganisation. When the luggage belonging to the schoolgirls of St Swithin’s arrives at Nutbourne College, Pond initially believes the arrival of over a hundred extra items of luggage to be the product of a mistake made by the railways. ‘This is what comes of nationalising the railways’, Pond declares, ‘The fellows don’t know their LMS from their Southern Region. I mean, instead of the ordinary muddle we’ve got complete chaos’. The film obliquely references the pre-war period as an era of stability, suggesting that the root of the order that befalls both Nutbourne and St Swithin’s is the administrative and social fallout from the Second World War. There are some wonderful gags within the film about nationalisation and post-war reorganisation. When the luggage belonging to the schoolgirls of St Swithin’s arrives at Nutbourne College, Pond initially believes the arrival of over a hundred extra items of luggage to be the product of a mistake made by the railways. ‘This is what comes of nationalising the railways’, Pond declares, ‘The fellows don’t know their LMS from their Southern Region. I mean, instead of the ordinary muddle we’ve got complete chaos’.

The film makes near-constant reference to the principle of ‘revacuation’, connecting the enforced movement of the children with the revacuation of children during the wartime years. Rainbow’s black market operations also allude to the rationing of the wartime and post-war eras: principally, Rainbow operates a scam in which he acquires and supplies black market petrol (petrol rationing ended in 1950, the year of the film’s release). Furthermore, the sequence in which Whitchurch suggests censoring the children’s outgoing mail so as not to let the pupils’ parents know that boys and girls are stationed at the school together echoes the postal censorship that took place during the war. The film is uncut, with a running time of 82:11 mins (PAL).

Video

Presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, the monochrome photography on this DVD release is handsomely recreated for this digital home video presentation. The source used for the transfer is clean and free of any issues that might impede one’s enjoyment of the film, and the contrast levels are good throughout – with strongly-defined mid-tones.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track. This is clean and clear, rich and rounded. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes a number of interviews: The disc includes a number of interviews:

- Andy Merriman (11:18). Merriman discusses Margaret Rutherford’s life and career, beginning with the extraordinary story of Rutherford’s childhood. He talks about Rutherford’s association with the play on which this film was based and her approach to the character. - Martin Rowson (8:19). Rowson’s interview focuses on Ronald Searle, who provided the cartoons used for the film’s opening titles. Rowson talks about Searle’s work as a cartoonist, his experiences in the war and his development of the St Trinian’s cartoons as a means of dealing with what he had seen and experienced in Burma. The St Trinian’s are funny ‘because they’re a hair’s breadth away from savage barbarity’, and Searle’s St Trinian’s cartoons draw on the iconography of his representations of the war. - Michael Brooke (12:29). Brooke discusses Dighton’s stage play and its origins, Launder’s decision to make the picture as a rival for the Ealing comedies of the period, and the longstanding partnership between Launder and Gilliat. The relationship between Happiest Days and the St Trinian’s films is also considered, with Brooke suggesting that the relationship between the this picture and the later The Belles of St Trinian’s isn’t as strong as is sometimes suggested – that the children in Happiest Days are quite well-behaved, in comparison with the rebellious girls of the St Trinian’s pictures.

Overall

Seemingly overshadowed in popular discourse by its thematic ‘sequel’, The Belles of St Trinian’s, The Happiest Days of Your Life is at the very least the equal of Launder’s subsequent school-set farce. It’s a very funny film, and although its immediate context has long since passed, the attitudes and stereotypes presented (and satirised) within the picture are still immediately recognisable, especially to those who work in education. Seemingly overshadowed in popular discourse by its thematic ‘sequel’, The Belles of St Trinian’s, The Happiest Days of Your Life is at the very least the equal of Launder’s subsequent school-set farce. It’s a very funny film, and although its immediate context has long since passed, the attitudes and stereotypes presented (and satirised) within the picture are still immediately recognisable, especially to those who work in education.

This DVD release contains a very pleasing presentation of the film, alongside some illuminating interviews. Fans of British comedy films should find this (or the concurrent Blu-ray release from the same distributor) to be an essential purchase. References: Babington, Bruce, 2002: British Film Makers: Launder & Gilliat. Manchester University Press Leach, Jim, 2004: British Film. Cambridge University Press Simpson, Mark, 2008: Alistair Sim: The Star of ‘Scrooge’ and ‘The Belles of St Trinian’s’. Gloucestershire: The History Press

|

|||||

|