|

The Film

Edgar Allan Poe’s Black Cats: Edgar Allan Poe’s Black Cats:

Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave/Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key/Gently Before She Dies (Sergio Martino, 1971) and Gatto nero/The Black Cat (Lucio Fulci, 1981)

The thrilling all’italiana is a slippery beast. Firstly, there’s the problem of definition and identification. English-speaking fans of Italian-style thrillers tend to use the label giallo to identify such films, whereas to Italian audiences a giallo is of course a thriller of any type, regardless of its country of origin – so a Hitchcock film is as much a giallo as a Mario Bava picture. Italian audiences tend to identify the distinctly Italian thrillers of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s as gialli all’italiana or examples of the thrilling all’italiana – specifically ‘Italian-style’ thrillers. Related to this issue of labeling is the debate, similar to that which exists in studies of American films noir, as to whether these films constitute a genre or may instead be considered a ‘style’. Attempts at structuralist analysis of the thrilling all’italiana may of course be made (and have been conducted in the past), but the Italian-style thriller is a wildly diverse subcategory of filmmaking, running the gamut from erotic melodramas and political thrillers to more outré supernatural thrillers. (The two films in Arrow’s Black Cats boxed set, Sergio Martino’s 1972 Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave/Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key and Lucio Fulci’s 1981 Gatto nero/The Black Cat, underscore this diversity.) Structuralist approaches to the Italian thriller are often undermined by a sense of confirmation bias – that the outliers, the films which don’t conform to the Bava-Argento ‘template’ (ie, the black gloved assassin, the whodunit structure), are either ignored or contorted to fit the hypothesis. Growing out of this, perhaps, is the suggestion that English-speaking fans arguably use the label giallo to denote a genre, whereas the Italian language designator (thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana) suggests a style (the ‘Italian-style’ of the name ascribed to this group of films).

Related to all of this are shifts in the dynamic of fandom surrounding the pictures themselves and their relative worth. In the 1980s, it seemed, Bava and Riccardo Freda (and to some extent Antonio Margheriti) were considered the forerunners of the Italian-style thriller. Argento’s reputation gradually caught up with these two more well-established filmmakers, perhaps owing to the arguably defining presence of his 1970s and 1980s films during the home video era. During the DVD boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, Freda’s films (which have largely been notably absent on digital home video formats owing to rights issues) fell out of favour with fans and Sergio Martino, whose films were given good service by companies like NoShame in the US during the mid-2000s, acquired a much bolder reputation – transferring from the ranks of metteurs-en-scene to be considered, within fan discourse at least, as an auteur in his own right. The DVD boom also allowed for a more balanced perspective on the films of Lucio Fulci, challenging the reductive association of Fulci’s style as a director with his zombie pictures and his 1980s horror films – and reminding audiences of just how good Fulci’s early thrilling all’italiana films are (for example, Non si sevizia un paperino/Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972). Related to all of this are shifts in the dynamic of fandom surrounding the pictures themselves and their relative worth. In the 1980s, it seemed, Bava and Riccardo Freda (and to some extent Antonio Margheriti) were considered the forerunners of the Italian-style thriller. Argento’s reputation gradually caught up with these two more well-established filmmakers, perhaps owing to the arguably defining presence of his 1970s and 1980s films during the home video era. During the DVD boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, Freda’s films (which have largely been notably absent on digital home video formats owing to rights issues) fell out of favour with fans and Sergio Martino, whose films were given good service by companies like NoShame in the US during the mid-2000s, acquired a much bolder reputation – transferring from the ranks of metteurs-en-scene to be considered, within fan discourse at least, as an auteur in his own right. The DVD boom also allowed for a more balanced perspective on the films of Lucio Fulci, challenging the reductive association of Fulci’s style as a director with his zombie pictures and his 1980s horror films – and reminding audiences of just how good Fulci’s early thrilling all’italiana films are (for example, Non si sevizia un paperino/Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972).

Considering, specifically, the two films in this boxed set, Il tuo vizio… received a rather snotty notice in The Aurum Film Encyclopedia: Horror (the bible of many a fan of European fantastique cinema during the videocassette era), which managed to confused the characters played in the film by Edwige Fenech and Anita Strindberg. However, after an early bootleg DVD release from Eurovista the critical fortunes of Il tuo vizio… turned in the film’s favour following the 2005 DVD release from NoShame. The film consolidates the relationship between the giallo all’italiana and the melodrama, upping the ante in terms of erotic content in comparison with similar films of its era. Fulci’s Gatto nero, on the other hand, suffered – as Stephen Thrower argues in the contextual material in this release – from panned-and-scanned (and often censored) home video presentations, at least until Redemption released the film letterboxed on VHS in the late 1990s. That release offered fans the opportunity to view cinematographer Sergio Salvati’s lush compositions in their full glory. Even with this, however, Gatto nero seemed overshadowed by the films Fulci made on either side of it (principally, his zombie pictures), Gatto nero’s mixture of the traditional thrilling all’italiana’s ‘whodunnit’ structure and elements of the supernatural seemingly alienating some viewers. (As Thrower argues in his interview on this disc, the film introduces some fascinating ideas – such as Patrick Magee’s character’s attempts to capture EVP recordings of the dead – but does nothing with them.)

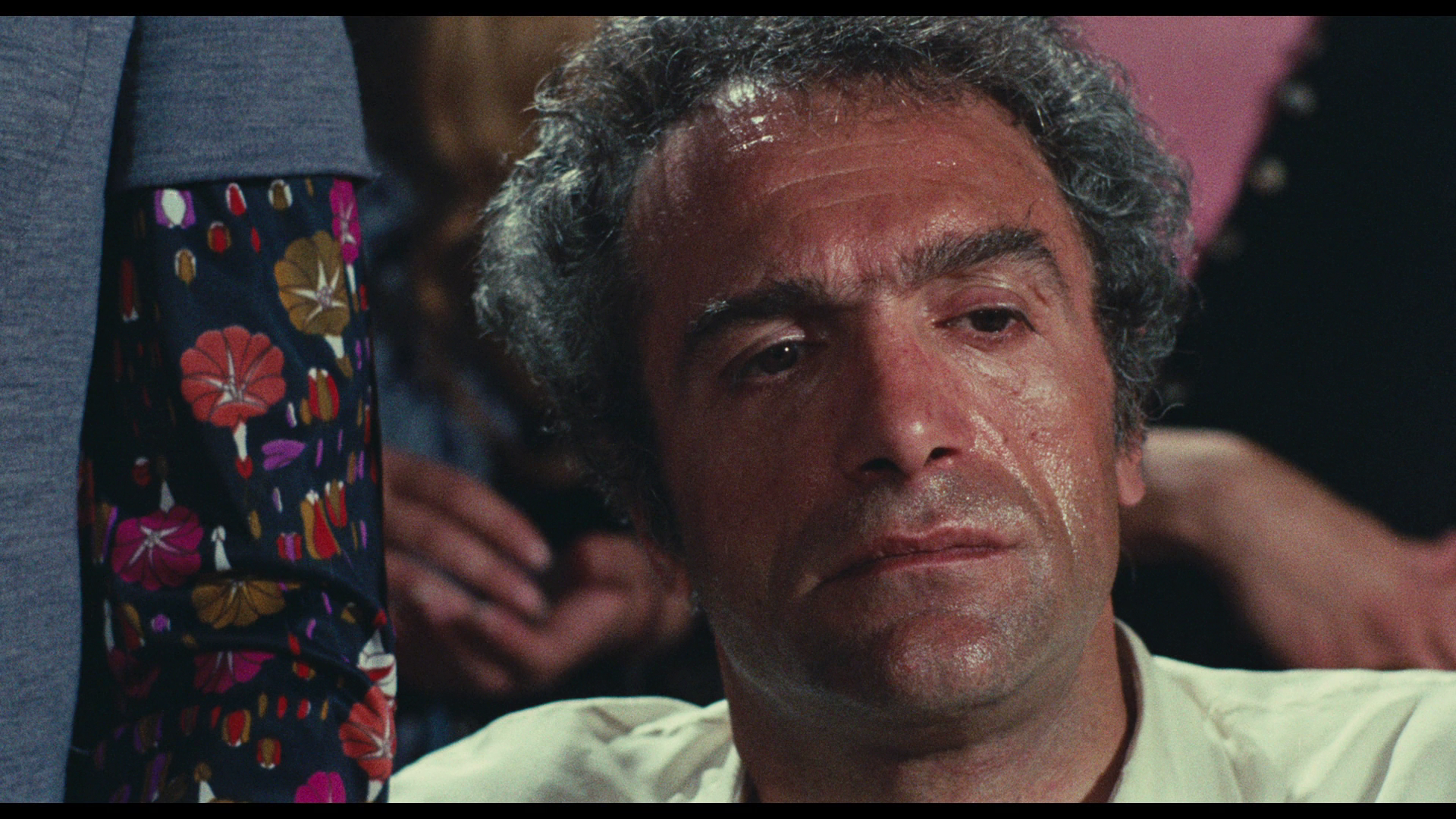

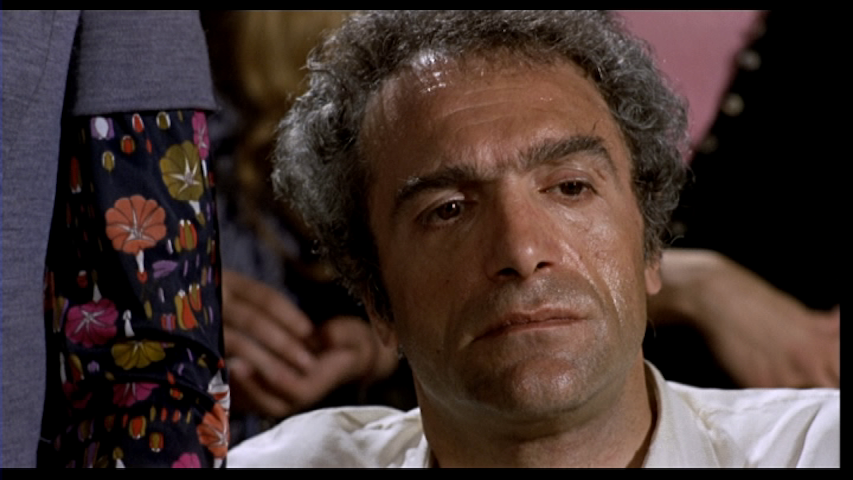

Il tuo vizio… focuses on alcoholic, washed-up writer and former teacher Oliviero Rouvigny (Luigi Pistilli) and his wife Irene (Anita Strindberg). The couple lead a decadent lifestyle, inviting young hippies from the nearby ‘Worldwide Campground’ to the Rouvigny villa for debauched parties filled with drinking and sex. At these parties, Oliviero seems to take great delight in humiliating his wife, taunting her thinly-veiled contempt for him (‘Maybe you’d prefer to drink from my empty skull’) and molesting their black maid Brenda (Angela La Vorgna) in front of the guests. Il tuo vizio… focuses on alcoholic, washed-up writer and former teacher Oliviero Rouvigny (Luigi Pistilli) and his wife Irene (Anita Strindberg). The couple lead a decadent lifestyle, inviting young hippies from the nearby ‘Worldwide Campground’ to the Rouvigny villa for debauched parties filled with drinking and sex. At these parties, Oliviero seems to take great delight in humiliating his wife, taunting her thinly-veiled contempt for him (‘Maybe you’d prefer to drink from my empty skull’) and molesting their black maid Brenda (Angela La Vorgna) in front of the guests.

One day, Oliviero arranges an illicit liaison with Fausta (Daniela Giordano), one of his former students, a young woman with whom Oliviero had an affair whilst he was her teacher. However, that evening Fausta is murdered brutally with a sickle. This results in the Rouvignys being visited by Inspector Farla, who is charged with investigating the murder of Fausta. Irene provides Oliviero with an alibi, though she appears to begin to suspect her husband of being involved in the murder of Fausta.

When Brenda is murdered with the same weapon and expires in front of Irene, Oliviero refuses to call the police (‘It’ll be like putting a noose around my neck. They’ll say I’m a maniac’) and asks for Irene’s help in hiding the corpse in the cellar of the villa.

Shortly after, the Rouvignys receive a telegram from Oliviero’s niece Floriana (Edwige Fenech) announcing her imminent arrival at the villa. From her arrival, Oliviero demonstrates an erotic fascination with Floriana. Soon, Irene too falls under Floriana’s spell: Floriana offers Irene a shoulder to cry on, and the two women are soon shown making love.

In town, the murderer claims yet another victim: a prostitute. Shortly after, Farla reveals that the owner of the bookshop in which Fausta worked, a man named Bartoli, escaped from a psychiatric institution eight years prior and ‘killed the two girls [Fausta and the prostitute] in a fit of madness’. However, this doesn’t explain the murder of Brenda, which Oliviero and Irene have apparently successfully covered up. In town, the murderer claims yet another victim: a prostitute. Shortly after, Farla reveals that the owner of the bookshop in which Fausta worked, a man named Bartoli, escaped from a psychiatric institution eight years prior and ‘killed the two girls [Fausta and the prostitute] in a fit of madness’. However, this doesn’t explain the murder of Brenda, which Oliviero and Irene have apparently successfully covered up.

Irene, however, refuses to believe that Oliviero is innocent. When Oliviero’s mother’s black cat, Satan, attackes Irene’s doves, Irene stabs the cat with a pair of scissors, blinding it. Aware of the cat’s absence, Oliviero becomes concerned for its welfare; this makes his relationship with Irene even more fractious. Adding to this is the input of Floriana, who begins to suggest to Irene that she could get away with murdering her cruel husband.

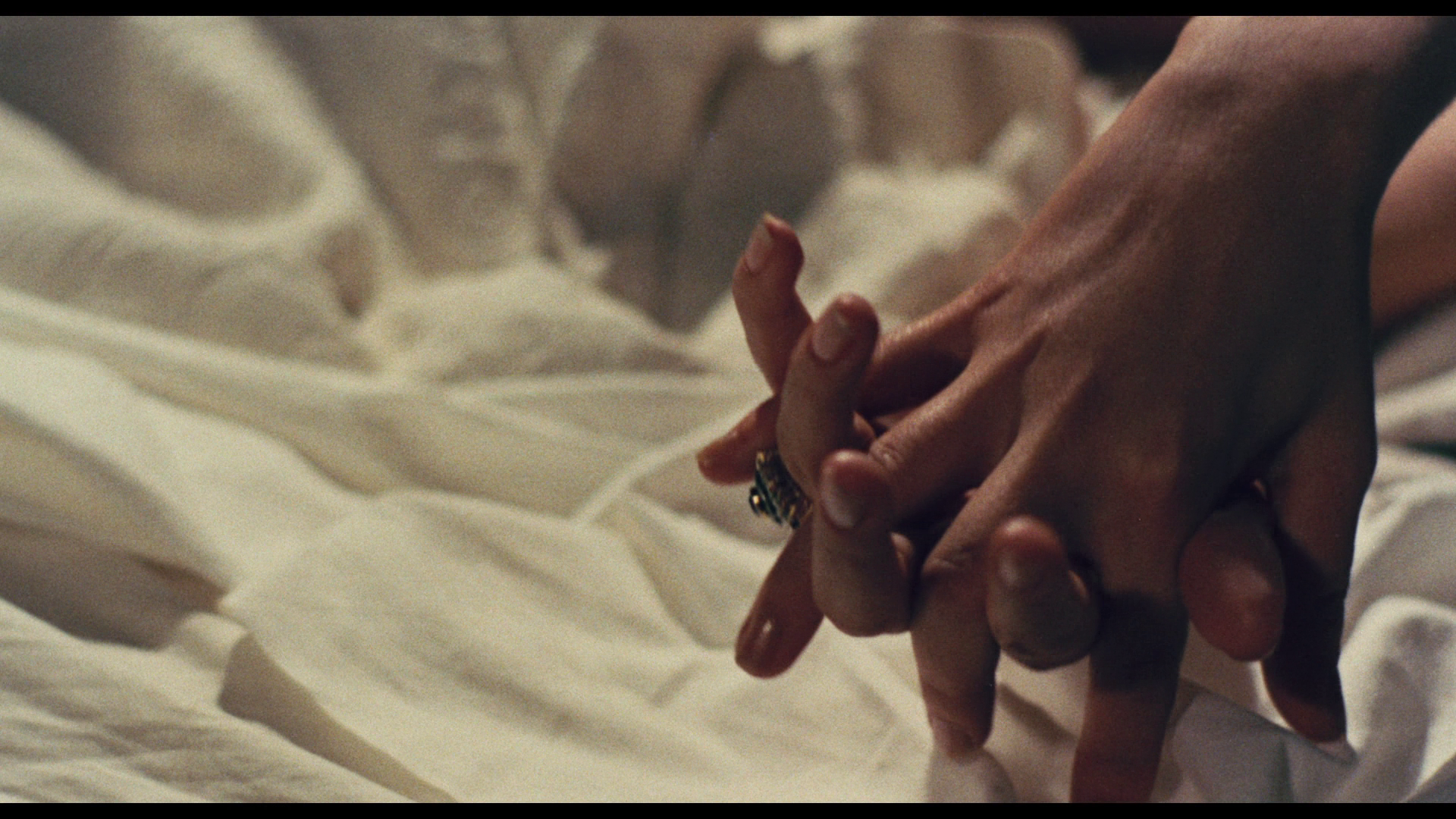

Underneath the opening credits of the film are soft-focus shots of two bodies making love on a bed: the metonymy of love-making recurs throughout the film. Later, it’s revealed that this moment is in fact a premonition of the love-making which takes place between Floriana and Irene, filmed in tight close-ups separated by dissolves. Martino uses many examples of metonymy within this (close-ups of hands clasping one another), foregrounding the importance of Floriana and Irene’s relationship within the narrative. It is Floriana that goads Irene into disposing of Oliviero, and she reminds Irene of the patriarchal assumptions that dominate society and which will result in her inevitable punishment: Floriana tells Irene that if Oliviero’s murder is discovered, Irene will get life as most judges are married ‘and it’s unlikely they’ll absolve a wife who’s…. understand? They defend their privileges’.

Within the film’s post-credits opening shots, the major motifs of the film are established: (i) a shot of the Rouvigny house at night, the windows lit yellow; (ii) a close-up of the eyes of Satan, the Rouvigny’s cat, his yellow eyes connected metonymically to the windows of the Rouvigny house; and (iii) the portrait of Oliviero’s mother dressed as Queen Mary. Oliviero’s Oedipus complex, and his fixation on this portrait of his mother, is established early in the film. Many compositions feature characters separated by the portrait of Oliviero’s mother dressed as Queen Mary, and the presence of Oliviero’s mother (or rather, her absence) hangs over the narrative. Her association with Queen Mary is a symbol of her ambiguous role in Oliviero’s life: as Oliviero says in relation to Queen Mary, ‘No one else has been represented in so many ways, as an assassin or a martyr. But she was a woman, a great woman’. During the party sequence which opens the film, a couple of the guests – out of Oliviero’s earshot – gossip about Oliviero’s mother: ‘Seems his mother was a great actress’, one guest says, ‘She made her career by sleeping around’; yet another guest highlights Oliviero’s fascination with his mother, ending with the assertion, ‘You know how these Italians are’. The dress worn by Oliviero’s mother in the painted portrait is also worn by almost all of the film’s major female characters: following the opening party, Irene dons the dress in order to excite or provoke Oliviero, resulting in the pair sharing a bout of rough lovemaking under the table. (‘What was your mother to you?’, Irene asks her husband in this scene, ‘Maria the madwoman? Or bloodthirsty Maria?’) Later, Oliviero has the hippies turned away whilst he sits drinking and staring at his mother’s portrait (‘Tell them I already have two tarts living here’, he commands Brenda), and as night falls Brenda tries on the Queen Mary dress. Oliviero watches on, silently and from the shadows. Shortly after, Brenda is killed by the sickle-wielding maniac. Later, Floriana puts on the dress too, and seduces Oliviero. Within the film’s post-credits opening shots, the major motifs of the film are established: (i) a shot of the Rouvigny house at night, the windows lit yellow; (ii) a close-up of the eyes of Satan, the Rouvigny’s cat, his yellow eyes connected metonymically to the windows of the Rouvigny house; and (iii) the portrait of Oliviero’s mother dressed as Queen Mary. Oliviero’s Oedipus complex, and his fixation on this portrait of his mother, is established early in the film. Many compositions feature characters separated by the portrait of Oliviero’s mother dressed as Queen Mary, and the presence of Oliviero’s mother (or rather, her absence) hangs over the narrative. Her association with Queen Mary is a symbol of her ambiguous role in Oliviero’s life: as Oliviero says in relation to Queen Mary, ‘No one else has been represented in so many ways, as an assassin or a martyr. But she was a woman, a great woman’. During the party sequence which opens the film, a couple of the guests – out of Oliviero’s earshot – gossip about Oliviero’s mother: ‘Seems his mother was a great actress’, one guest says, ‘She made her career by sleeping around’; yet another guest highlights Oliviero’s fascination with his mother, ending with the assertion, ‘You know how these Italians are’. The dress worn by Oliviero’s mother in the painted portrait is also worn by almost all of the film’s major female characters: following the opening party, Irene dons the dress in order to excite or provoke Oliviero, resulting in the pair sharing a bout of rough lovemaking under the table. (‘What was your mother to you?’, Irene asks her husband in this scene, ‘Maria the madwoman? Or bloodthirsty Maria?’) Later, Oliviero has the hippies turned away whilst he sits drinking and staring at his mother’s portrait (‘Tell them I already have two tarts living here’, he commands Brenda), and as night falls Brenda tries on the Queen Mary dress. Oliviero watches on, silently and from the shadows. Shortly after, Brenda is killed by the sickle-wielding maniac. Later, Floriana puts on the dress too, and seduces Oliviero.

Oliviero’s obsession with the image of his mother (‘Tell me, is it true you slept with your mother in her bed? I mean, when you’d grown up?’, Floriana taunts him at one point) is just one of his perversions. We learn that as a teacher, he apparently made a habit of sleeping with his students. (‘You started working on me over the desks at high school, sir, and now you’ll pay the price’, Fausta tells him.) Furthermore, from her arrival Oliviero demonstrates a sexual obsession with Floriana. As she steps off the train, Oliviero looks lustfully at her. ‘Be careful with shocks’, Floriana warns him, ‘At your age you might have a heart attack’. However, the free-spirited Floriana is a match for Oliviero. She has lived in a commune – ‘Where the women are everyone’s’, Oliviero suggests. ‘Where the men are everyone’s’, Floriana corrects him sharply. ‘He’s a bit retarded about sex’, Irene offers in relation to her husband, ‘and terrified of impotence. Literary impotence, of course’. To this, Oliviero responds: ‘Sex is an activity which only interests those who have imagination as well as the means. Irene has neither’. When Floriana retreats with her milkman-cum-motocross racer boyfriend to an abandoned hayloft to make love, she is aware of the presence of Oliviero – who watches from the shadows. Shortly afterwards, she throws herself at Oliviero. ‘You really are the little whore I thought you were’, he says. ‘And are you really the pig they say you are?’, she asks.

Oliviero’s status as a dried-up writer who has turned to drink and debauchery is arguably a cliché but works within the context of the film. When he and Irene discover that Fausta has been murdered, Oliviero suggests that he may be ‘A bad writer but a good sadistic murderer. Who knows if I’ll become one some day, and it’ll be your throat’s turn?’ Oliviero’s days as a successful author seem long gone: at one point, Irene declares that ‘Oliviero says the novel’s dead. In truth, it’s him who’s dead [….] The only thing he can sell these days is the furniture’. However, with the arrival of Floriana and the series of murders, Oliviero seems to get his writing ‘mojo’ back, locking himself in his study where, from the outside, Irene can hear the clatter of the keys on his typewriter. She enters the room and discovers that Oliviero has typed the phrase: ‘Kill her and hide her in the cellar wall’. In response, Irene stabs Oliviero with the scissors – and appears to kill him. However, shortly afterwards Floriana hears the clatter of the typewriter’s keys again, and entering the room discovers that someone – perhaps Oliviero – has typed repeatedly the word ‘Revenge’. (Here, and in its depiction of Oliviero’s domestic cruelty, Il tuo vizio… seems to anticipate Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of Stephen King’s novel The Shining.) Oliviero’s status as a dried-up writer who has turned to drink and debauchery is arguably a cliché but works within the context of the film. When he and Irene discover that Fausta has been murdered, Oliviero suggests that he may be ‘A bad writer but a good sadistic murderer. Who knows if I’ll become one some day, and it’ll be your throat’s turn?’ Oliviero’s days as a successful author seem long gone: at one point, Irene declares that ‘Oliviero says the novel’s dead. In truth, it’s him who’s dead [….] The only thing he can sell these days is the furniture’. However, with the arrival of Floriana and the series of murders, Oliviero seems to get his writing ‘mojo’ back, locking himself in his study where, from the outside, Irene can hear the clatter of the keys on his typewriter. She enters the room and discovers that Oliviero has typed the phrase: ‘Kill her and hide her in the cellar wall’. In response, Irene stabs Oliviero with the scissors – and appears to kill him. However, shortly afterwards Floriana hears the clatter of the typewriter’s keys again, and entering the room discovers that someone – perhaps Oliviero – has typed repeatedly the word ‘Revenge’. (Here, and in its depiction of Oliviero’s domestic cruelty, Il tuo vizio… seems to anticipate Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of Stephen King’s novel The Shining.)

The Rouvignys are the subject of gossip within the nearby town. As Farla declares, ‘the most popular entertainment in town is gossiping’ about the Rouvignys and their visitors from the Worldwide Campgrounds. The Rouvignys parties are debauched; as a drunken, lethargic Oliviero sits at the head of the table during the party which opens the film, one young woman climbs on the table and declares ‘It’s clothes that ruin the world. Naked, we’re all the same’ before taking off her clothes and dancing naked for the others. Mrs Molinar (Nerina Montagnani), a former servant of Oliviero’s mother, comments in one scene that Oliviero and his wife’s ‘friends’ are ‘from the campsite: lunatics, Krauts, and foreigners’. (Another local promises, ‘You can’t even imagine what goes on at Villa Rouvigny’.) Oliviero’s treatment of his wife is cruel. During the opening party sequence, he has the guests pour their drinks into a punchbowl and forces Irene to drink from it. However, Olivierio also has a profound contempt for those ‘hangers on’ from the Worldwide Campgrounds who attend is parties: ‘It’s easy for these youngsters to think they’re something’, he says, ‘when it’s obvious they are nothing’.

By contrast with the Italian villa setting of Il tuo vizio…, Fulci’s Gatto nero takes place in an English village. The film begins with the death of a man in a road accident: whilst in his car, the man is attacked by a black cat, which causes him to crash the vehicle. In the same village, whilst documenting the local architectural ruins (with the aid of a very nice Hasselblad), American photographer Jill (Mimsy Farmer) discovers an underground cavern that seems to be an ancient torture chamber: within the cavern are skeletons which are strung from the ceiling by irons and tied to racks. Emerging from the underground cavern, Jill meets local policeman Wilson (Al Cliver), who warns her to leave the dead alone. By contrast with the Italian villa setting of Il tuo vizio…, Fulci’s Gatto nero takes place in an English village. The film begins with the death of a man in a road accident: whilst in his car, the man is attacked by a black cat, which causes him to crash the vehicle. In the same village, whilst documenting the local architectural ruins (with the aid of a very nice Hasselblad), American photographer Jill (Mimsy Farmer) discovers an underground cavern that seems to be an ancient torture chamber: within the cavern are skeletons which are strung from the ceiling by irons and tied to racks. Emerging from the underground cavern, Jill meets local policeman Wilson (Al Cliver), who warns her to leave the dead alone.

Meanwhile, Maureen Grayson (Daniela Doria) and her boyfriend Stan hide in a boathouse, the ‘Swan’s Haunt’, in order to engage in a spot of illicit lovemaking. However, they find themselves trapped in the boathouse when the key with which they have locked the door from the inside disappears, and the air conditioning unit – the only source of breathable air in the room – mysteriously ceases to work. The pair, it seems, are destined to suffocate. Maureen’s mother Lillian (Dagmar Lassander) soon notices her daughter’s disappearance. In discovering what has happened to Maureen, Lillian seeks the help of Professor Robert Miles (Patrick Magee), her former lover and a parapsychologist who uses a reel-to-reel tape recorder to try to capture the voices of the dead in the local cemetery. His work is the subject of local gossip, and has led him to be ostracised within the community.

His interest piqued by Maureen’s disappearance, Wilson seeks the help of Scotland Yard. That help takes the form of Inspector Gorley (David Warbeck), whose unconventional attitude is signposted by his arrival in the village on a speeding motorcycle. (‘An epidemic of accidents. Isn’t it curious?’, Gorley declares in relation to the spate of deaths within the village.) When another man – the town drunk who has previously been seen mocking Miles in the village pub – is killed by the cat, Gorley enlists Jill’s help in photographing the crime scene. Jill pays particular attention to the claw marks on the man’s hand, which mirror the scratches she saw made on Miles’ hand by the black cat with which he lives. She confronts Miles, who claims that the cat is demonic and is able to hypnotise its victims.

Miles uses a psychic parlour trick to lead the police to the Swan’s Haunt, the location of the bodies of Maureen and Stan. Gorley comes to believe Jill’s claims that Miles’ cat is somehow involved in the crimes. Meanwhile, Miles attempts to kill the cat by doping it and then hanging it from a tree in the garden. However, this just results in a burst of paranormal activity and seems to heighten the cat’s powers. The cat launches an attack on Gorley, and following this Jill becomes trapped in the home of Miles – who appears to be wholly under the influence of the infernal cat. Miles uses a psychic parlour trick to lead the police to the Swan’s Haunt, the location of the bodies of Maureen and Stan. Gorley comes to believe Jill’s claims that Miles’ cat is somehow involved in the crimes. Meanwhile, Miles attempts to kill the cat by doping it and then hanging it from a tree in the garden. However, this just results in a burst of paranormal activity and seems to heighten the cat’s powers. The cat launches an attack on Gorley, and following this Jill becomes trapped in the home of Miles – who appears to be wholly under the influence of the infernal cat.

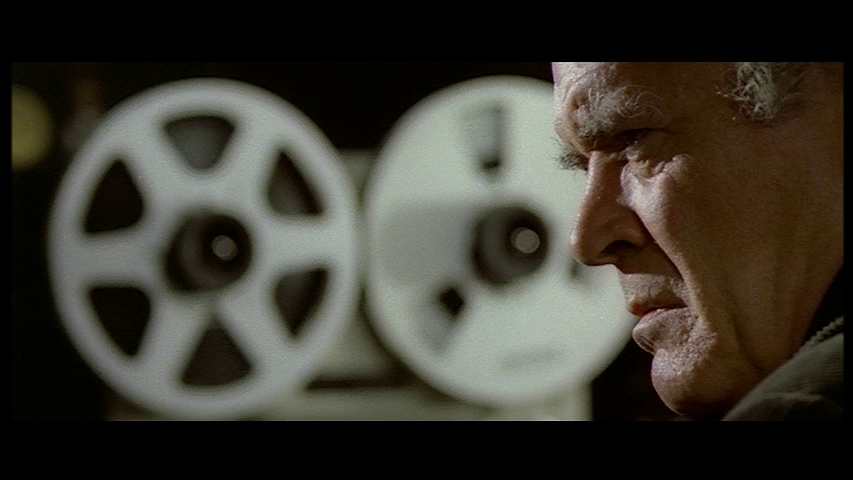

As the above synopsis might suggest, Gatto nero’s narrative is essentially a patchwork quilt of ideas. As Stephen Thrower suggests in the contextual material on this disc, Gatto nero introduces a number of narrative strands which are frustratingly underdeveloped. Chief among these are Miles’ attempts to record EVP via his reel-to-reel tape recorder in the village cemetery. (‘We used to be friends. Tell me where you are’, he begs whilst placing his recorder on a grave.) Miles’ nocturnal activities make him the subject of local gossip: ‘Professor Miles is crazy’, a man in the village pub tells Jill, ‘You’d better stay away from him’. When we first see Miles, he is listening to his recordings in the comfort of his large home. We hear a series of sounds: a woman screaming; a low voice whispering ‘You’re a spy’; a child singing; laughter; another voice declaring ‘We can’t…’. ‘I record their [the dead’s] voices, and I decipher them with my machines’, Miles tells Jill when they first meet, informing her that he does this at nighttime and in secret because he fears people’s ‘stupidity and meanness. These idiots think I desecrate graves. But some men have supernatural powers that go beyond the imagination. Abilities we cannot control’. ‘Or that we choose to ignore because we’re scared of them’, Jill offers. ‘I have those powers’, Miles says, ‘and it’s my duty to use them. Death is not the end of everything. It’s the beginning of a new existence’. Although it connects to the warning Wilson issues Jill early in the film (that she should leave the dead alone because ‘they’re grumpy’), this narrative strand sadly goes nowhere: little is done with it. However, it taps into the interest in parapsychology and EVP during the 1970s – the latter popularised by Konstantin Raudive in his 1968 book Breakthrough: An Amazing Experiment in Electronic Communication, and at the end of the 1970s by William O’Neil’s Spiricom device. Another strand which is frustratingly underdeveloped is the bizarre torture chamber that Jill finds underground in one of the film’s early scenes. Whilst photographing the village’s ruins, she discovers the entrance to an underground cavern filled with skeletons attached to various torture devices. However, Jill emerges from this nightmare to encounter Wilson, who tells her to leave the dead alone because ‘They’re grumpy’ – and the cavern is never mentioned again.

To some extent, the film is anchored by Patrick Magee’s performance as Miles: he is the character around which the mystery revolves. The character of Robert Miles was, apparently, originally intended to have been played by Peter Cushing; but Cushing backed out of the project, with speculation suggesting that Cushing’s departure from the film was owing to a lack of assurance from the makers that the cats involved in the production would not be harmed (see Gullo, 2004: 318). Wheeler Winston Dixon has argued that Magee ‘brings to the role an aura of genuine menace and authority, and serves as a suitable counterbalance to the rest of the film, which, in typical Fulci style, eschews narrative structure for a series of violent deaths’ (Dixon, 2010: 141). Miles, Dixon suggests, ‘has entombed himself in the manner of many of Poe’s protagonists’, locking himself within ‘a country house that no one visits’ where he is ‘already one of the living dead’ (ibid.). To some extent, the film is anchored by Patrick Magee’s performance as Miles: he is the character around which the mystery revolves. The character of Robert Miles was, apparently, originally intended to have been played by Peter Cushing; but Cushing backed out of the project, with speculation suggesting that Cushing’s departure from the film was owing to a lack of assurance from the makers that the cats involved in the production would not be harmed (see Gullo, 2004: 318). Wheeler Winston Dixon has argued that Magee ‘brings to the role an aura of genuine menace and authority, and serves as a suitable counterbalance to the rest of the film, which, in typical Fulci style, eschews narrative structure for a series of violent deaths’ (Dixon, 2010: 141). Miles, Dixon suggests, ‘has entombed himself in the manner of many of Poe’s protagonists’, locking himself within ‘a country house that no one visits’ where he is ‘already one of the living dead’ (ibid.).

Louis Paul has argued that with Gatto nero, Fulci attempted to make ‘a more cerebral and supernatural thriller than a violent, excessive gory monster rampage’ (Paul, 2005: 127). The film inverts the Poe story on which it is based, depicting the black cat as a demonic beast whose fate is intertwined with that of Miles. ‘It’s our fate’, Miles tells Jill, ‘A common hatred is our bond. It’s a devilish creature’. ‘But it’s just a cat’, Jill protests. ‘A cat that sooner or later is going to kill me. I’ll die like him. It’s my fate’, Miles asserts. Later, Jill observes that ‘they’ll [the police] think we’re crazy if we say it’s a cat’ that has committed the murders. ‘It’s the fate of those in the know’, Miles tells her cynically. When Jill discovers the nature of Miles’ relationship with the cat, she attempts to warn Gorley – who is resistant at first but soon comes to realise the truth. ‘Why don’t they teach parapsychology in your academies?’, Jill asks Gorley. ‘It would be black magic’, Gorley states. The cat seems to be capable of supernatural feats (for example, hypnotising its victims, and apparently multiplying itself in front of them) that in some ways connect it with the ghostly ‘zombies’ in Fulci’s Paura nella città dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead, 1980) which, apparently absent of any corporeal existence, are able to appear and disappear within the blink of an eye. Gatto nero and Paura nella città dei morti viventi both have a similar ‘texture’ of swirling fog, small town gossip and superstition, and a fascination with the practices of mediumship and parapsychology. When Miles appears to hang the cat in the garden of his house (‘Even death was defeated by it [the cat]’, Miles later reflects), Jill experiences a burst of paranormal phenomena that seem to allude to the paradigms of demonic intercession films popularised by William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), including a levitating bed and an imploding window. (The iconography of the latter would also find its way into Fulci’s ...E tu vivrai nel terrore! L'aldilà/The Beyond, 1981.) In terms of intertextual allusions, Gatto nero also contains a restaging of the bat attacks, clearly inspired by the sequence in Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) in which Tippi Hedren is assaulted by the titular beasts whilst exploring an attic, which had appeared in Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, 1971) and Quella villa accanto al cimitero (The House by the Cemetery, 1981): in the case of this film, it’s Jill who’s attacked by the bats whilst exploring Miles’ house. She escapes only to be knocked unconscious by Miles.

Fulci intersperses the narrative with point-of-view shots from the titular cat’s perspective, shot from a low-angle and using a wide-angle lens. The scenes of the cat interacting with its human victims are filmed like showdowns in a western all’italiana, the psychic standoff communicated through tight close-ups of the cat’s eyes juxtaposed with close-ups of the eyes of the humans with which it is interacting. At first, Jill believes that the cat is simply under the influence of a human – that Miles has hypnotised the creature into doing his bidding, ridding him of those who have criticised his work or made him the object of ridicule within the village. ‘Let’s suppose that he [the cat] is just an instrument’, Jill says at one point, ‘That his mind is dominated by another – by a human mind’. However, she soon comes to realise that it is the cat’s will that is dominating Miles: ‘Cats don’t take orders from anyone, my dear’, Miles informs her, ‘It was that monster that triggered my repressed hatred and provoked my rage for those who don’t understand me, for the loneliness in which they forced me to live. The beast didn’t obey me, only the worst side of me: the devil that is hidden in me, as in everyone’. That cat, Miles suggests, ‘annihilated my will. From now on it can only give orders. It’s evil. It dominates me now’. In this respect, as Stephen Thrower argues in the contextual material on this disc, Gatto nero has some similarities with David Cronenberg’s roughly contemporaneous film The Brood (1979), in which Hal Raglan’s practice of psychoplasmics (a parody of the many therapies that became popular during the 1970s) focuses on the externalisation of inner emotions by giving them a physical form (‘the shape of rage’). Where in Raglan’s schema, psychoplasmics is intended to empower his clients and give them control over their lives, Gatto nero is – like a number of Fulci’s other films, including L’aldila and Paura nella città dei morti viventi – riddled with a profound sense of fatalism, offering a world in which the characters are stripped of their free will and any sense of agency. Fulci intersperses the narrative with point-of-view shots from the titular cat’s perspective, shot from a low-angle and using a wide-angle lens. The scenes of the cat interacting with its human victims are filmed like showdowns in a western all’italiana, the psychic standoff communicated through tight close-ups of the cat’s eyes juxtaposed with close-ups of the eyes of the humans with which it is interacting. At first, Jill believes that the cat is simply under the influence of a human – that Miles has hypnotised the creature into doing his bidding, ridding him of those who have criticised his work or made him the object of ridicule within the village. ‘Let’s suppose that he [the cat] is just an instrument’, Jill says at one point, ‘That his mind is dominated by another – by a human mind’. However, she soon comes to realise that it is the cat’s will that is dominating Miles: ‘Cats don’t take orders from anyone, my dear’, Miles informs her, ‘It was that monster that triggered my repressed hatred and provoked my rage for those who don’t understand me, for the loneliness in which they forced me to live. The beast didn’t obey me, only the worst side of me: the devil that is hidden in me, as in everyone’. That cat, Miles suggests, ‘annihilated my will. From now on it can only give orders. It’s evil. It dominates me now’. In this respect, as Stephen Thrower argues in the contextual material on this disc, Gatto nero has some similarities with David Cronenberg’s roughly contemporaneous film The Brood (1979), in which Hal Raglan’s practice of psychoplasmics (a parody of the many therapies that became popular during the 1970s) focuses on the externalisation of inner emotions by giving them a physical form (‘the shape of rage’). Where in Raglan’s schema, psychoplasmics is intended to empower his clients and give them control over their lives, Gatto nero is – like a number of Fulci’s other films, including L’aldila and Paura nella città dei morti viventi – riddled with a profound sense of fatalism, offering a world in which the characters are stripped of their free will and any sense of agency.

Video

Both films have been restored in 2k from their camera negatives. Each picture is contained on its own disc, with each film taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. Both films have been restored in 2k from their camera negatives. Each picture is contained on its own disc, with each film taking up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

As each disc starts up, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the respective film with English onscreen text or with Italian onscreen text. The difference is negligible, but it’s wonderful to be presented with the option nevertheless.

Both films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. Both films are also completely uncut.

Il tuo vizio… is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with a running time of 96:43. If the viewer selects to watch the film with English onscreen text, he/she will see the film’s title presented as Gently Before She Dies. Contrast levels are very good in this presentation, offering a well-balanced image that handles the many night-time scenes towards the end of the picture very nicely. This is the most noticeable improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases. There’s a superb level of detail present, which is particularly noticeable in close-ups (see some of the large screengrabs at the bottom of this review). The photography within the film contains a mixture of zoom lenses, wide angles and short telephoto lenses, and the different qualities of these lenses are evident within this presentation. The presentation has a warmer hue than the presentation of the film on NoShame’s 2005 DVD release, and has a more film-like appearance as a result. Finally, a superb encode ensures that the presentation contains an organic amount of film grain and has the appearance of 35mm film – or as close to this as a digital simulacrum will currently allow.

Gatto nero is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with a running time of 91:55. The presentation here is remarkably crisp, with a strong level of detail on display and a depth to the image that is a characteristic of the 2-perf Techniscope format, which the film was shot in: freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to use lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops. The depth of field within the photography of Gatto nero is communicated through Salvati’s use of short focal lengths and facilitated by the strengths of this HD presentation: the presentation conveys the strong depth of field, a defining paradigm of Salvati’s camerawork, very well. In some shots, a vertical line is present on the right-hand side of the frame; this was present in the same shots on the film’s previous home video releases, and its presence in some shots and not others suggests that the film’s negative was scratched during processing. There’s also very slight density fluctuation in a couple of shots. (Additionally, there’s a strange example of light diffraction contained within a shot at 23:55, which would seem to be a product of the original photography.) These very minor instances of ‘damage’ would seem to be inherent within the source material and shouldn’t impair the viewer’s enjoyment of the film; certainly, they’re present in the film’s other home video releases. Contrast levels are impressive, again offering a big improvement over the film’s previously-available DVD releases. As with Il tuo vizio, the film is presented through a characteristically robust encode which ensures that the picture has the organic qualities of 35mm film. Gatto nero is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with a running time of 91:55. The presentation here is remarkably crisp, with a strong level of detail on display and a depth to the image that is a characteristic of the 2-perf Techniscope format, which the film was shot in: freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to use lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops. The depth of field within the photography of Gatto nero is communicated through Salvati’s use of short focal lengths and facilitated by the strengths of this HD presentation: the presentation conveys the strong depth of field, a defining paradigm of Salvati’s camerawork, very well. In some shots, a vertical line is present on the right-hand side of the frame; this was present in the same shots on the film’s previous home video releases, and its presence in some shots and not others suggests that the film’s negative was scratched during processing. There’s also very slight density fluctuation in a couple of shots. (Additionally, there’s a strange example of light diffraction contained within a shot at 23:55, which would seem to be a product of the original photography.) These very minor instances of ‘damage’ would seem to be inherent within the source material and shouldn’t impair the viewer’s enjoyment of the film; certainly, they’re present in the film’s other home video releases. Contrast levels are impressive, again offering a big improvement over the film’s previously-available DVD releases. As with Il tuo vizio, the film is presented through a characteristically robust encode which ensures that the picture has the organic qualities of 35mm film.

NB. Included at the bottom of this review are some large screen grabs comparing Arrow’s new HD presentations of Il tuo vizio… and Gatto nero with each film’s previous ‘benchmark’ DVD release (in the case of Il tuo vizio…, the 2005 DVD release from NoShame; in the case of Gatto nero, the 2007 DVD release from Blue Underground).

Audio

Both films are presented with the choice of an Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track, with accompanying optional English subtitles; and an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track, with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

In the case of Il tuo vizio…, both the Italian and English tracks are clean and free of issues. Good range is evident from the opening bars of the film’s baroque main titles music, by Bruno Nicolai, which makes use of a harpsichord and clavinet in its orchestration. The Italian track seems very slightly clipped at the top end, but this is barely noticeable; on the other hand, the English track seems much more ‘bassy’. The English dub for this film isn’t too bad, and it follows the ‘gist’ of the Italian dialogue quite closely. The voices in the English dub sound a little unnatural, however. The Italian track sounds much more natural, by contrast.

Gatto nero features a predominantly English-speaking central cast (Warbeck, Magee, Mimsy Farmer), and these actors were clearly speaking English on the set. However, the Italian language version is a little wittier. Both tracks are clean and problem free, with a strong sense of range resulting in a lovely, rich sound that showcases Pino Donaggio’s unconventional score. The English and Italian dialogue differ in a number of ways. When Jill first meets Wilson at the crypt she discovers, in the Italian track Wilson tells Jill to leave the dead alone as ‘they’re grumpy’. ‘I didn’t think policemen were superstitious’, Jill declares. ‘Perhaps in London they aren’t. But in a village like ours…’. IN the English, dub this final line becomes the far less evocative, ‘Maybe in America. Here we all believe in certain things’. Later, when Gorley encounters Jill, Wilson tells Gorley that Jill is a photographer who is there to document the ruins. ‘I’d like to see them’, Gorley says in the English track. ‘The ruins, sir?’, Wilson asks. ‘The photographs’, Gorley says – and Wilson lets out a little chuckle. In the Italian track, Gorley says, ‘I like them a lot’. ‘What? Ruins?’, Wilson asks. ‘No, girls like her’, Gorley responds – and Wilson’s subsequent chuckle seems to make more sense within this context.

Extras

DISC ONE: Your Vice is a Locked Room… And Only I Have the Key

- ‘Through the Keyhole: An Interview with Sergio Martino’ (34:42). Martino discusses the origins of the film and the source of the title on a nude given to Fenech’s character in Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh. Martino reflects on shooting the film in a village near Padua, and reveals that the character played by Fenech was adapted to fit her screen persona: in the original script, the character was significantly younger. - ‘Through the Keyhole: An Interview with Sergio Martino’ (34:42). Martino discusses the origins of the film and the source of the title on a nude given to Fenech’s character in Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh. Martino reflects on shooting the film in a village near Padua, and reveals that the character played by Fenech was adapted to fit her screen persona: in the original script, the character was significantly younger.

Martino reflects on the influence of Poe’s work on his own films. He also suggests that the infamous Fenaroli murder, which took place in Italy during the late 1950s, influenced a number of his thrillers. Another influence on Il tuo vizio… was Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques (1955). Martino reflects on the popularity of Italian genre films amongst international audiences, saying that ‘I think they [the films] were better than the critics thought at the time, but not as good as today’s fans think they are’. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Unveiling the Vice’ (23:07). Carried over from NoShame’s American 2005 DVD release of the film, this featurette takes a look at the production of the film and features input from Sergio Martino, Edwige Fenech and Ernesto Gastaldi. Martino confesses that Il tuo vizio… ‘wasn’t one of my favourites’: it’s ‘a story about the Italian provinces’ that has a ‘timeless’ quality. Fenech reflects on her role in the film, saying that (as Quentin Tarantino told her), it was the first time she played ‘the bad girl’ and she ‘went from being the victim to the tormentor’. Gastaldi suggests that the films got a new lease of life when they were shown on Italian television. All three discuss the shooting of the film and their memories of Luigi Pistilli. Martino discusses some of the ways in which filmmaking has changed, suggesting that part of the charm of earlier cinema was in the ‘archaic’ technology: today, with the use of monitors on set, a director can spot if the camera operator has made a mistake immediately, whereas in the 1970s such a mistake would only be apparent when the dailies were screened. The interviews are in Italian with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Dolls of Flesh and Blood’ (29:04). This visual essay by Michael Mackenzie takes a look at Sergio Martino’s examples of the thrilling all’italiana. I’d take very slight issue with Mackenzie’s description of the giallo all’italiana as a ‘movement’, as the films never had a manifesto and it wasn’t organised and orchestrated in the sense that, for example, the Futurist movement was. Mackenzie doesn’t make overstated claims for Martino’s status as an auteur, instead arguing that Martino is one of a group of ‘journeyman’ directors who made interesting films within the parameters of the thrilling. - ‘Dolls of Flesh and Blood’ (29:04). This visual essay by Michael Mackenzie takes a look at Sergio Martino’s examples of the thrilling all’italiana. I’d take very slight issue with Mackenzie’s description of the giallo all’italiana as a ‘movement’, as the films never had a manifesto and it wasn’t organised and orchestrated in the sense that, for example, the Futurist movement was. Mackenzie doesn’t make overstated claims for Martino’s status as an auteur, instead arguing that Martino is one of a group of ‘journeyman’ directors who made interesting films within the parameters of the thrilling.

Martino’s films, Mackenzie argues, define the popular perception of Italian-style thrillers. Mackenzie begins with Il dolce corpo di Deborah (The Sweet Body of Deborah, Romolo Guerrieri, 1968) as an example of the ‘languidly paced sexy melodramas’ that were shaken up by Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1969).

Mackenzie discusses Martino’s first three thrilling pictures as director: La coda dello scorpione (The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail, 1971); Tutti I colori del buio (All the Colors of the Dark, 1972); and Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh, 1971). What Martino did, Mackenzie argues, was ‘marry’ the paradigms of the melodramas of the late 1960s with the ‘bodycount’ approach established by Argento in his directorial debut. This differentiated Martino’s films from those of many of his contemporaries. A byproduct of this is that the films feel like ‘hybrids’ and often feature ‘abrupt shifts […] in location and tone’ – and can sometimes feature ‘multiple killers, often operating completely independently’.

Fenech’s presence anchors these films, though La coda dello scorpione ‘suffers from her absence’. Also, as Mackenzie argues, the films are enriched by the performances of George Hilton. The films form part of what Mackenzie suggests are ‘jet set gialli’.

Mackenzie suggests that Il tuo vizio… is Martino’s most ‘distinctive’ thrilling film. The film was released the same day as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perche quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972), which also starred Edwige Fenech – the latter being a far more mundane example of the thrilling all’italiana. Martino’s film has apparently an acknowledged influence in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques (1955) but makes the homosexual undertones of Clouzot’s film more explicit and front-and-centre within the drama. Mackenzie suggests that Il tuo vizio… is Martino’s most ‘distinctive’ thrilling film. The film was released the same day as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perche quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972), which also starred Edwige Fenech – the latter being a far more mundane example of the thrilling all’italiana. Martino’s film has apparently an acknowledged influence in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les diaboliques (1955) but makes the homosexual undertones of Clouzot’s film more explicit and front-and-centre within the drama.

- ‘The Strange Vice of Ms Fenech’ (29:41). Justin Harries reflects on Edwige Fenech’s career, situating this within the unrest experienced by Italian society during the 1970s. Harries tries to explain Fenech’s appeal and the contrast between her public persona and her private life. Fenech’s pre-Martino pictures are discussed and glossed over, but Harries focuses in greater detail on Fenech’s work within the thrilling all’italiana – and looks a little at the history of the giallo all’italiana. Harries argues that Il tuo vizio… is like ‘the work of Sartre filmed through a psychosexual lens’. There’s some discussion of Fenech’s work within the comedia sexy pictures of the late 1970s too.

- ‘Eli Roth on Your Vice’ (9:17). Roth’s use of the misappropriated plural ‘giallos’ grates a little, but he shows abundant enthusiasm for the film. Roth argues, slightly reductively, that the giallo all’italiana was ‘really the precursor of the Amercian slasher film’. Roth focuses particularly on how Il tuo vizio…, along with other Italian films of the era, capture the post-counterculture era and the transition from Italy of the 1960s to the Italy of the 1970s.

DISC TWO: The Black Cat

- Audio commentary with Chris Alexander. Alexander, the editor of Fangoria, offers a commentary that reflects on Alexander’s enjoyment of Fulci’s films and aims to understand their appeal for audiences. Alexander also discusses Gatto nero’s relationship with some of Fulci’s other pictures. It’s a lightweight, engaging commentary with an ad-hoc structure which works in its favour. - Audio commentary with Chris Alexander. Alexander, the editor of Fangoria, offers a commentary that reflects on Alexander’s enjoyment of Fulci’s films and aims to understand their appeal for audiences. Alexander also discusses Gatto nero’s relationship with some of Fulci’s other pictures. It’s a lightweight, engaging commentary with an ad-hoc structure which works in its favour.

- ‘Poe Into Fulci: The Spirit of Perverseness’ (25:37). In this featurette, Stephen Thrower reflects on Fulci’s Gatto nero, suggesting that the film doesn’t quite have the fanbase of Fulci’s zombie pictures owing to its relative lack of grue. Thrower discusses the picture’s origins in Edgar Allan Poe’s story ‘The Black Cat’, a story which is about ‘the spirit of perverseness’.

The adaptation of the Poe story was by Biagio Proietti, who had previously contributed to an Italian television series which adapted a number of Poe’s stories for the small screen, I racconti fantastici di Edgar Allan Poe (1979). Fulci’s film inverts Poe’s story by depicting the cat as the agent of evil, resulting in ‘the very spirit of the story [being] changed’. Thrower also suggests that Proietti’s script has some interesting similarities with David Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979).

Thrower also considers some of the similarities and differences between Fulci’s take on ‘The Black Cat’ and Dario Argento’s approach to the same story in Two Evil Eyes (1990). Both Fulci and Argento’s takes on Poe incorporate elements of other Poe stories too.

Thrower highlights the Fulci film’s frustrating lack of ‘pay off’ to Miles’ attempts to record the voices of the dead – something which is given an awful lot of screen time but which leads nowhere. The script has ‘so many unexplored avenues, so many loose fragments that you think could be developed into something more but which remain inscrutable’. Thrower suggests that this has its own sense of pleasure for a viewer, in the sense that it makes the film feel like ‘a junction between different ideas’. However, it can also be frustrating.

Thrower also reflects on the film’s superb music by Pino Donaggio and the wonderful photography by Sergio Salvati, and suggests that the film’s reputation was for a long time hampered by the fact that it was released on videocassette in a panned-and-scanned format. Fans of Fulci’s films tended to ‘prioritise’ the films Fulci made either side of Gatto nero, but in retrospect this picture is ‘cut from the same cloth’ as Fulci’s other, more famous pictures. Thrower also reflects on the film’s superb music by Pino Donaggio and the wonderful photography by Sergio Salvati, and suggests that the film’s reputation was for a long time hampered by the fact that it was released on videocassette in a panned-and-scanned format. Fans of Fulci’s films tended to ‘prioritise’ the films Fulci made either side of Gatto nero, but in retrospect this picture is ‘cut from the same cloth’ as Fulci’s other, more famous pictures.

- ‘In the Paw-Prints of the Black Cat’ (8:28). In this fascinating short piece, Thrower visits some of the locations used within the film.

- ‘Frightened Dagmar’ (20:12). In this interview, actress Dagmar Lassander reflects on her career. She discusses her first film appearances, and her notable appearances in Andrea (Hans Schott-Shobinger, 1968) and Von Haut zu Haut (Hans Schott-Shobinger, 1969). The latter was a particularly negative experience and Lassander felt she didn’t have ‘control’ over the nudity within the picture; the unpleasantness of this experience led to Lassander reneging on her three picture contract and forgoing any payment. The interview is in German, with optional English subtitles.

Lassander reflects positively on Piero Schivazappa’s Femina ridens (1969), referring to it as ‘a well-made, beautiful film’. This film, as well as many of the later pictures Lassander made in Italy, was shot in English. Lassander offers brief comments on many of the films she made subsequently. She talks in some detail about her work with Fulci, who she refers to as ‘the king of horror films’. Via a telephone conversation, Lassander reflects on the shooting of the scene in Gatto nero in which her character burns to death, suggesting that the effect nearly went disastrously wrong because the technicians had ‘misunderstood Fulci’s specifications’.

- ‘At Home with David Warbeck’ (70:19). This extensive interview with David Warbeck, shot on videotape during the 1990s, features Warbeck, ever the raconteur, reflecting on the films he made in Italy. The interview is broken up into a number of topics separated by the use of onscreen titles.

Trailer (3:00).

Retail copies of the release are housed within a special boxed set, limited to 3000 copies. Each film is housed in its own Amaray case which features reversible sleeve artwork, and the boxed set also contains an eight page book which includes the Edgar Allan Poe short story, a transcript of Lucio Fulci’s final interview and new writing about both of the films. This lavish book is illustrated throughout with stills from the films.

Overall

Both Il tuo vizio… and Gatto nero offer variations on some of Poe’s themes – and both pictures are wildly different from one another, highlighting the oft-ignored or deliberately overlooked diversity of the thrilling all’italiana. Fulci’s film is arguably much closer in tone to the spirit of Poe than the Martino picture, though both films build towards a climax which alludes directly to the events within Poe’s ‘The Black Cat’. Both pictures also display a profoundly pessimistic view of human nature, reflecting the concerns of their respective directors. In a scene in Il tuo vizio…, Farla and Oliviero share a drink in the town, and Farla declares, ‘European integration’s not bad […] Here we are, in a beautiful Veneto town, with German beer, Scotch whisky…’ ‘And atomic condiments for everyone’, Oliviero adds dryly. ‘That’s the trouble with you intellectuals: pessimism’, Farla tells him. ‘Is there anything to laugh about?’, Oliviero asks. Although Fulci’s film has a more absurd, dryly humorous tone than the Martino picture, both films offer a profoundly bleak depiction of the world. Both Il tuo vizio… and Gatto nero offer variations on some of Poe’s themes – and both pictures are wildly different from one another, highlighting the oft-ignored or deliberately overlooked diversity of the thrilling all’italiana. Fulci’s film is arguably much closer in tone to the spirit of Poe than the Martino picture, though both films build towards a climax which alludes directly to the events within Poe’s ‘The Black Cat’. Both pictures also display a profoundly pessimistic view of human nature, reflecting the concerns of their respective directors. In a scene in Il tuo vizio…, Farla and Oliviero share a drink in the town, and Farla declares, ‘European integration’s not bad […] Here we are, in a beautiful Veneto town, with German beer, Scotch whisky…’ ‘And atomic condiments for everyone’, Oliviero adds dryly. ‘That’s the trouble with you intellectuals: pessimism’, Farla tells him. ‘Is there anything to laugh about?’, Oliviero asks. Although Fulci’s film has a more absurd, dryly humorous tone than the Martino picture, both films offer a profoundly bleak depiction of the world.

The presentation of both pictures in this boxed set is very good: both films contain handsome new transfers, restored from the films’ respective negatives, and both discs also include some very good contextual material.

References:

Dixon, Wheeler Winston, 2010: A History of Horror. Rutgers University Press

Gullo, Christopher, 2004: In all Sincerity… Peter Cushing. Indiana: Xlibris

Paul, Louis, 2005: Italian Horror Film Directors. London: McFarland and Company

Comparisons with previous DVD releases.

Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

NoShame’s 2005 DVD.

Gatto nero

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Arrow’s Blu-ray.

Blue Underground’s 2007 DVD.

Il tuo vizio è una stanza chiusa e solo io ne ho la chiave

Gatto nero

|