|

|

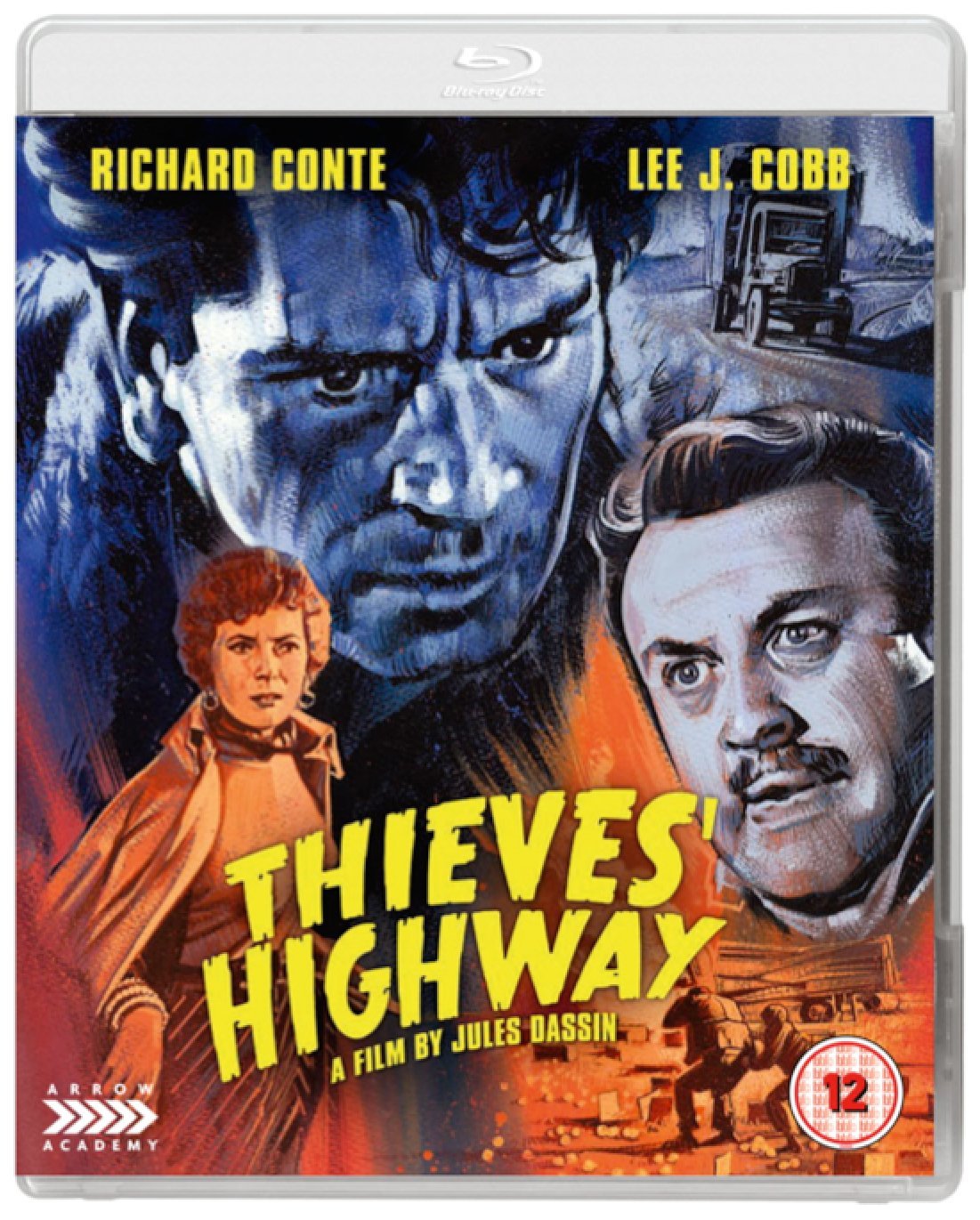

Thieves' Highway AKA Collision AKA The Thieves' Market (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th October 2015). |

|

The Film

Thieves’ Highway (Jules Dassin, 1949) Thieves’ Highway (Jules Dassin, 1949)

Adapted by A I Bezzerides from his own novel, and directed by Jules Dassin, the 1949 picture Thieves’ Highway represents the melding of two of the great talents associated with the classic era of film noir. Both Dassin and Bezzerides were fascinated, in their own way, with social realism: Bezzerides documented the lives of the working classes, drawing on his own experiences; meanwhile, Dassin, in American films such as The Naked City (1948), had evidenced a progressive fascination with street-level reality. Dassin’s Hollywood career would be swiftly curtailed by the arrival of the McCarthy era, and Thieves’ Highway was the last film Dassin completed in America before being blacklisted after being ‘outed’ as a Communist by Hollywood Ten member Edward Dmytryk. Dassin would be blacklisted during the production of his next film, Night and the City (1950) – another literary adaptation, this time of Gerald Kersh’s 1938 social realist crime novel – and was frozen out of that picture’s post-production. Subsequent to this, Dassin would carve out a new career as a filmmaker in Europe that began with Rififi (1953). The film revolves around Nick Garcos (Richard Conte), a war veteran who returns to his family in Fresno after visiting exotic places – presumably after taking jobs on commercial ships following the war. Nick is greeted by his lover Polly (Barbara Lawrence), his father Yanko (Morris Carnovsky) and his mother Parthena (Tamara Shayne). He has brought with him presents for each member of his family, but is shocked and outraged to discover that his father – for whom Nick has bought a pair of mandarin slippers from China – is in a wheelchair, having lost both of his legs. Nick discovers that Yanko, a truck driver, was hauling goods to sell to San Francisco produce wholesaler Mike Figlia (Lee J Cobb) and, on his return journey, found himself involved in a nasty accident of which he had no memory and which resulted in the loss of his legs – and the mysterious disappearance of his money. Nick surmises that ‘He [Yanko] never got paid. They just got him drunk, put him in his truck and sent him home’. Nick promises to ‘gouge your [Yanko’s] money out of Mike Figlia’s carcass’. To do so, Nick needs to take Yanko’s truck – but Yanko has sold it to an associate, Ed Kinney (Millard Mitchell).  Nick speaks with Ed, who is planning to buy a load of Golden Delicious apples and ship them to San Francisco to sell at a profit. Ed just needs an investor. Nick invests twelve hundred dollars in this venture, and Ed waves off the other two men with whom he was originally to collaborate, Pete (Joseph Pevney) and Slob (Jack Oakie). Nick and Ed buy the apples from Polansky (Norbert Schiller), the orchard owner – but not before Ed tries to ‘gyp’ Polansky out of three hundred dollars, much to Nick’s disgust. Nick speaks with Ed, who is planning to buy a load of Golden Delicious apples and ship them to San Francisco to sell at a profit. Ed just needs an investor. Nick invests twelve hundred dollars in this venture, and Ed waves off the other two men with whom he was originally to collaborate, Pete (Joseph Pevney) and Slob (Jack Oakie). Nick and Ed buy the apples from Polansky (Norbert Schiller), the orchard owner – but not before Ed tries to ‘gyp’ Polansky out of three hundred dollars, much to Nick’s disgust.

Nick and Ed drive south with the apples in two trucks: Nick in front and Ed behind. A tyre blows out on Nick’s truck. Nick attempts to jack the truck up and replace the tyre, but he doesn’t support the jack properly ad it collapses, the truck coming down on Nick and burying his face in the sand. He is saved by Ed, who comes across the desperate scene just in time, dragging Nick out from under the truck and saving the younger man’s life. (‘Next time you’ll know better than to try to jack up a truck with the back of your neck’, Ed advises Nick.) The relationship between the two men has thus been repaired. Arriving in San Francisco ahead of Ed, Nick meets with Figlia, who stages a trick on Nick: he has one of the tyres of Nick’s truck slashed, thus forcing Nick to leave his truck outside Figlia’s place of business. Whilst Nick visits a café and meets a good time girl, Italian immigrant Rica (Valentina Cortese), who takes Nick up to her room to rest, Figlia begins to strip Nick’s truck of crates of the prized ‘Golden Delish’ apples, selling each crate for six and a half dollars. Rica, who has been hired to ‘distract’ Nick, takes a shine to Nick and warns him of Figlia’s plan. Nick confront s Figlia, demanding three thousand and nine hundred dollars for his truckload of apples – which is the amount Figlia will receive for selling them at six and a half dollars per crate. Figlia argues with Nick but eventually relents, offering Nick five hundred dollars in cash and a cheque for the rest.  Nick telephones his family and tells them of his good fortune, demanding that Polly fly down to San Francisco immediately so they may be married. Afterwards, Nick meets up with Rica and, grateful for her tip-off as to Figlia’s plan, offers to buy her a drink. The two hit it off, but walking back to Rica’s place at night they are attacked by two of Figlia’s goons. Nick is knocked unconscious and Rica takes Nick’s money and runs, hoping to protect it from Figlia’s men. Sadly, they catch up with Rica and steal the money from her. Nick telephones his family and tells them of his good fortune, demanding that Polly fly down to San Francisco immediately so they may be married. Afterwards, Nick meets up with Rica and, grateful for her tip-off as to Figlia’s plan, offers to buy her a drink. The two hit it off, but walking back to Rica’s place at night they are attacked by two of Figlia’s goons. Nick is knocked unconscious and Rica takes Nick’s money and runs, hoping to protect it from Figlia’s men. Sadly, they catch up with Rica and steal the money from her.

Meanwhile, outside the city Ed is struggling to make time. He is faced with the realisation that if he doesn’t reach San Francisco by sun up, the apples will be spoiled. He is taunted by Pete and Slob, who are hauling another load to San Francisco. Near the city, as the sun is rising, Ed’s truck’s drive shaft breaks and his brakes fail, causing a devastating crash in which Ed burns to death whilst the apples his truck was carrying are scattered across a field. When Pete and Slob arrive in San Francisco and meet up with Figlia, to whom they intend to sell their own load, Pete tells Figlia about the accident and suggests returning to the scene to collect the spilled apples. Slob is disgusted. ‘What are you, a couple of grave robbers’, Slob protests angrily, ‘Pete, you seen that guy burn [….] If you ever see me again, you’d better be on the other side of the street’. When Slob encounters Nick in the city, he tells Nick of Ed’s death and Pete and Figlia’s plan to steal the apples from the scene of the crash. Nick is angered and, together with Slob, seeks out Figlia and Pete. He finds the wholesaler in a roadside café and confronts him, discovering that even Figlia’s associates – including Pete – round on the corrupt conman/upstanding capitalist.  Thieves’ Highway is a film about hunger and poverty. The structure of the picture, as Emmett Early has suggested, ‘has an Odyssean ring to it’ (Early, 2014: 165). The character of Rica, Early argues, had immediate resonance within the post-war context in which the film was made: she ‘embodies the brutalized citizenry of war-torn Europe, when otherwise decent people found their morality compromised by necessity’ (ibid.: 166). The picture explores the alienation of men (and women) from the means of production. Polansky sells the apples to Ed and Nick, who transport them down to Figlia. Ed tries to ‘gyp’ Polansky, and in turn Figlia attempts to rob Nick and Ed. The prized Golden Delicious apples might as well be made of pure gold: at one point, Nick tells Rica, ‘You know what it takes to get an apple so you can sink your beautiful teeth in it? You gotta stuff rags up tailpipes, farmers gotta get gypped, you jack up trucks with the back of your neck, “universals” conk out…’ Nick’s speech foregrounds for Rica and the film’s viewer the extent to which the production and distribution of an item we take for granted (the apple, in this instance) is the product of (and symbol for) a hidden nexus of blood, sweat, hard labour and exploitation – a fact we often ignore, or choose to overlook. Thieves’ Highway is a film about hunger and poverty. The structure of the picture, as Emmett Early has suggested, ‘has an Odyssean ring to it’ (Early, 2014: 165). The character of Rica, Early argues, had immediate resonance within the post-war context in which the film was made: she ‘embodies the brutalized citizenry of war-torn Europe, when otherwise decent people found their morality compromised by necessity’ (ibid.: 166). The picture explores the alienation of men (and women) from the means of production. Polansky sells the apples to Ed and Nick, who transport them down to Figlia. Ed tries to ‘gyp’ Polansky, and in turn Figlia attempts to rob Nick and Ed. The prized Golden Delicious apples might as well be made of pure gold: at one point, Nick tells Rica, ‘You know what it takes to get an apple so you can sink your beautiful teeth in it? You gotta stuff rags up tailpipes, farmers gotta get gypped, you jack up trucks with the back of your neck, “universals” conk out…’ Nick’s speech foregrounds for Rica and the film’s viewer the extent to which the production and distribution of an item we take for granted (the apple, in this instance) is the product of (and symbol for) a hidden nexus of blood, sweat, hard labour and exploitation – a fact we often ignore, or choose to overlook.

As the film opens, Nick’s status as a man of the world is established quickly, when he reveals the presents he has bought for his family – and scares Polly with a ritualistic mask he acquired ‘from one of the cannibal islands’. He establishes himself as different from Yanko, asserting ‘You’re a pushover, pop’ when he discovers how Mike Figlia has conned the older man. Nick’s rhetoric speaks of the brutality he has witnessed; that the war has exposed him to. Nick promises not simply to return Yanko’s money but to ‘gouge it out of Mike Figlia’s carcass’. Shortly after, when he enters into the deal with Ed, Nick warns the other man, ‘Gyp me, and I’ll cut your heart out’. For his part, Ed offers Nick some advice: ‘Look, kid’, he says, ‘This ain’t no lace pants business. It takes tricks to get what you want in this game’.  As the film progresses, Nick finds himself the object of a number of ‘tricks’. One of the most significant of these is Figlia’s hiring of Rica to ‘distract’ Nick whilst Figlia and his crew strip Nick’s truck of the prized apples. This plan goes awry, however: Nick goes with Rica to her room, but only to rest. Rica tries to seduce Nick but, remembering Polly, Nick resists. At this point, Rica seems to be the prototypical femme fatale of many films noir. However, perhaps inspired by Nick’s integrity Rica begins to warm to Nick, and warns him of Figlia’s plan to essentially steal the produce in his truck. As the film progresses, Nick finds himself the object of a number of ‘tricks’. One of the most significant of these is Figlia’s hiring of Rica to ‘distract’ Nick whilst Figlia and his crew strip Nick’s truck of the prized apples. This plan goes awry, however: Nick goes with Rica to her room, but only to rest. Rica tries to seduce Nick but, remembering Polly, Nick resists. At this point, Rica seems to be the prototypical femme fatale of many films noir. However, perhaps inspired by Nick’s integrity Rica begins to warm to Nick, and warns him of Figlia’s plan to essentially steal the produce in his truck.

Nick and Rica discover that they are unified by their identities as immigrants (or, in Nick’s case, a second-generation immigrant) but separated by this also. ‘You’re French?’, Nick asks Rica. ‘Italian’, she replies. ‘Oh, I went swimming in Italy once [….] A beach, a little place called Anzio’, Nick tells Rica in one of script’s very few direct references to the war, before rebutting her attempt to seduce him with the comment, ‘You look like chipped glass’. The ‘seduction’ scene between Nick and Rica depicts the relationships between men and women as like a battlefield – a metaphoric place in which words act like bullets and a glance can have the destructive impact of a bomb. Later, after Nick has learnt that Rica is an ally, Rica warns Nick about Polly: ‘She marries you for your money’. Nick dismisses her assertion as simply a moment of bitterness. However, when Polly arrives in San Francisco Nick experiences a more honest moment of bitterness: Polly is angered by Nick’s association with Rica, however innocent it may be. ‘It’s a pleasant surprise, I must say, finding you in her room’, Polly declares. ‘Where do you want me to be?’, Nick asks, ‘In the gutter with my head busted open? She took care of me’. Polly soon proves Rica’s assessment of her character to be correct, complaining to Nick that he essentially allowed himself to be mugged and asserting angrily that ‘I don’t suppose you have enough money to send me home, or to feed me, even. You see, I’m hungry; but I’d rather go hungry one morning than for the rest of my life’. With that, Polly storms out, and in response to this Rica states, ironically, ‘Aren’t women wonderful?’ The film’s narrative, whilst establishing the traditional pure/fallen woman dualism often found in films noir, subverts the archetypes initially associated with Polly and Rica, respectively – proving by the end of the picture that Rica is the ‘pure’, faithful woman, whilst Polly is the film’s true femme fatale.  Thieves’ Highway was famously identified, along with twelve other pictures (including Robert Rossen’s 1947 Body and Soul and Abraham Polonsky’s 1948 Force of Evil) as a film gris by Thom Andersen in his studies of the work of filmmakers affected by the Hollywood blacklists. Andersen suggests that the film gris is a subgenre of the film noir that developed as a response ‘to the threat of political repression’: the films themselves ‘relied upon the conventions of film noir’ but ‘tried to achieve a “greater psychological and social realism”’ (Anderson, quoted in Naremore, 1998: 124). Andersen labeled these films as examples of film gris owing to the association ‘we have [… of] Communism with drabness and greyness’ and because the pictures themselves were ‘often drab and depressing’ (Andersen, quoted in ibid.) Similarly, Barry Gifford argues that Dassin’s picture ‘is a typical proletarian melodrama that pits one earnest man against an exploitative, corrupt businessman attempting to control a marketplace’ (Gifford, 2001: 169). Certainly, Thieves’ Highway’s depiction of economics within the world of fresh produce, the savage and inhuman thumbing-under of individuals within a system that is simply engineered towards the accumulation of wealth for those who already have some of it, seems like a none-too-subtle metonymic representation of capitalism more generally. Thieves’ Highway was famously identified, along with twelve other pictures (including Robert Rossen’s 1947 Body and Soul and Abraham Polonsky’s 1948 Force of Evil) as a film gris by Thom Andersen in his studies of the work of filmmakers affected by the Hollywood blacklists. Andersen suggests that the film gris is a subgenre of the film noir that developed as a response ‘to the threat of political repression’: the films themselves ‘relied upon the conventions of film noir’ but ‘tried to achieve a “greater psychological and social realism”’ (Anderson, quoted in Naremore, 1998: 124). Andersen labeled these films as examples of film gris owing to the association ‘we have [… of] Communism with drabness and greyness’ and because the pictures themselves were ‘often drab and depressing’ (Andersen, quoted in ibid.) Similarly, Barry Gifford argues that Dassin’s picture ‘is a typical proletarian melodrama that pits one earnest man against an exploitative, corrupt businessman attempting to control a marketplace’ (Gifford, 2001: 169). Certainly, Thieves’ Highway’s depiction of economics within the world of fresh produce, the savage and inhuman thumbing-under of individuals within a system that is simply engineered towards the accumulation of wealth for those who already have some of it, seems like a none-too-subtle metonymic representation of capitalism more generally.

Imogen Sara Smith has suggested that with Thieves’ Highway, Bezzerides and Dassin ‘slice[d] open the produce business to reveal the rotten heart of capitalism’ (Smith, 2011: 14). It’s a picture in which ‘something as pure and nourishing as an apple becomes a poisoned agent of strife when it’s equated with money’ (ibid.). It’s a film that is haunted throughout by the spectre of cash: ‘dirty crumpled bills changing hands in a series of soiled, coercive transactions’ (ibid.). To begin with, the first of these transactions is between Nick, Ed and the Polanskys who own the orchard where the treasured Golden Delicious apples grow. Nick gives Ed twelve hundred dollars to buy the apples, but Ed underpays Polansky – giving the orchard owner nine hundred dollars. This results in a conflict between Ed and Polansky, who begins attempting to tear the crates of apples from the truck, and between Ed and Nick. Nick breaks this by demanding that Ed ‘Give him [Polansky] his money’. This results in Mrs Polansky (Kasia Orzazewski) praising Nick’s honesty and sense of justice: it’s a moment in which Nick demonstrates a sense of solidarity with the Polanskys (as members of the same social class, and as members of immigrant families too) which foreshadows the solidarity amongst the workers which results in Nick meting out justice (at the end of his fists) to Figlia at the end of the picture. The next of these transactions is between Nick and Figlia, who Nick is warned against upon arriving in San Francisco (‘Hey, what do you want to get mixed up with him [Figlia] for?’, a man asks Nick, ‘There are plenty of straight outfits on the street’). Many of the resultant scenes feature Figlia attempting to con Nick or Slob and Pete, and pretty much anyone else with whom he comes into contact. Figlia has no sense of ethics whatsoever, lying to his customers about how much the apples have cost him so that he can sell them for a higher price, and lying to Pete about how much he bought the apples from Nick for so that Figlia may ‘buy’ the apples stolen from Ed’s truck at a lower price.  The film establishes the difference between the producers, hauliers and the wholesalers along both ethnic and class-based lines; perhaps surprisingly for a Hollywood production of the era, there are a wide variety of accents and languages spoken in the picture, with a number of scenes featuring Greek, Russian and Italian language spoken by characters in the background. The producer of the apples, Polansky, is Russian. He gets the rawest deal of the lot, selling his apples to Ed and Nick (the hauliers of Greek heritage) for a dollar per box. (Ed has the gumption to take twelve hundred dollars from Nick and try to buy the apples from Polansky for nine hundred dollars in total – seventy-five cents per box. Polansky becomes irate, and Nick overrides his partner, paying Polansky the producer the full rate – and thus establishing Nick as a man of principle, who won’t shaft another for his own financial gain.) Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Figlia (the Italian-American wholesaler) is able to sell the ‘Golden Delish’ for over six dollars per box but tries to stiff Nick by offering him as little as two dollars – and then having Nick ‘mugged’ by Figlia’s goons-for-hire, so that the money is returned to Figlia before it has been spent or banked. At the end of the film, the drivers display a solidarity with one another as Nick squares off against Figlia – who in one way or another has played the ‘long con’ with each of them. With regards the ethnic conflict within the film between Greeks and Italians, Donald Dewey says in his biography of Lee J Cobb that ‘there was nothing abstract about the conflict on view, least of all to second-generation immigrants hooked on the American dream’ (Dewey, 2014: 118). The film establishes the difference between the producers, hauliers and the wholesalers along both ethnic and class-based lines; perhaps surprisingly for a Hollywood production of the era, there are a wide variety of accents and languages spoken in the picture, with a number of scenes featuring Greek, Russian and Italian language spoken by characters in the background. The producer of the apples, Polansky, is Russian. He gets the rawest deal of the lot, selling his apples to Ed and Nick (the hauliers of Greek heritage) for a dollar per box. (Ed has the gumption to take twelve hundred dollars from Nick and try to buy the apples from Polansky for nine hundred dollars in total – seventy-five cents per box. Polansky becomes irate, and Nick overrides his partner, paying Polansky the producer the full rate – and thus establishing Nick as a man of principle, who won’t shaft another for his own financial gain.) Meanwhile, in San Francisco, Figlia (the Italian-American wholesaler) is able to sell the ‘Golden Delish’ for over six dollars per box but tries to stiff Nick by offering him as little as two dollars – and then having Nick ‘mugged’ by Figlia’s goons-for-hire, so that the money is returned to Figlia before it has been spent or banked. At the end of the film, the drivers display a solidarity with one another as Nick squares off against Figlia – who in one way or another has played the ‘long con’ with each of them. With regards the ethnic conflict within the film between Greeks and Italians, Donald Dewey says in his biography of Lee J Cobb that ‘there was nothing abstract about the conflict on view, least of all to second-generation immigrants hooked on the American dream’ (Dewey, 2014: 118).

In The Heist Film: Stealing with Style (2014), Daryl Lee reflects on Claude Chabrol and Francois Truffaut’s 1964 dialogue focusing on the auteur theory and its relationship with the production contexts in which a film is made (Lee, 2014: 114). In their dialogue, Chabrol and Truffaut reflected on the ways in which films like Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway were perhaps so vibrant because they were made within a system that their makers resisted or felt constrained by. ‘We used to say we liked the American cinema’, Chabrol suggests, ‘but its filmmakers were slaves’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). The question as to ‘what would it be like if they [these filmmakers] were free men?’ was answered by the movement of directors like Dassin to Europe: ‘the moment they become free they make lousy films. The moment Dassin is free, he goes to Greece and makes Celui qui doit mourir [He Who Must Die]’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). The French auteurist critics, Chabrol argues, underestimated ‘how vital it was, for the American cinema, to work in these conditions’: the conditions of ‘assembly-line cinema, where the director was an operative for four weeks of shooting, where the film was edited by someone else’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). In response to this, Truffaut observes that filmmakers like Dassin were, in Hollywood, ‘prisoners and tried to escape’ but, perversely, ‘bec[a]me a lot more cautious and timid than before’ when they escaped from the constrictive Hollywood system: ‘It’s a crazy thing’, Truffaut adds, ‘I’m sure today [in 1960s Europe] Dassin couldn’t even imagine doing Thieves’ Highway’ (Truffaut, quoted in ibid.). To this, Chabrol argues that Thieves’ Highway, in its depiction of the cruel extremes of capitalism and the ways in which a man can be pinned down and brutalised by commerce, is ‘not a film that a free man wants to make. You have to be on the payroll to make this film – it was good payroll cinema’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). In The Heist Film: Stealing with Style (2014), Daryl Lee reflects on Claude Chabrol and Francois Truffaut’s 1964 dialogue focusing on the auteur theory and its relationship with the production contexts in which a film is made (Lee, 2014: 114). In their dialogue, Chabrol and Truffaut reflected on the ways in which films like Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway were perhaps so vibrant because they were made within a system that their makers resisted or felt constrained by. ‘We used to say we liked the American cinema’, Chabrol suggests, ‘but its filmmakers were slaves’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). The question as to ‘what would it be like if they [these filmmakers] were free men?’ was answered by the movement of directors like Dassin to Europe: ‘the moment they become free they make lousy films. The moment Dassin is free, he goes to Greece and makes Celui qui doit mourir [He Who Must Die]’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). The French auteurist critics, Chabrol argues, underestimated ‘how vital it was, for the American cinema, to work in these conditions’: the conditions of ‘assembly-line cinema, where the director was an operative for four weeks of shooting, where the film was edited by someone else’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.). In response to this, Truffaut observes that filmmakers like Dassin were, in Hollywood, ‘prisoners and tried to escape’ but, perversely, ‘bec[a]me a lot more cautious and timid than before’ when they escaped from the constrictive Hollywood system: ‘It’s a crazy thing’, Truffaut adds, ‘I’m sure today [in 1960s Europe] Dassin couldn’t even imagine doing Thieves’ Highway’ (Truffaut, quoted in ibid.). To this, Chabrol argues that Thieves’ Highway, in its depiction of the cruel extremes of capitalism and the ways in which a man can be pinned down and brutalised by commerce, is ‘not a film that a free man wants to make. You have to be on the payroll to make this film – it was good payroll cinema’ (Chabrol, quoted in ibid.).

The film is here presented uncut, with a running time of 94:01 mins. (Please also see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Dassin’s The Naked City here.)

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1 and in 1080p (using the AVC codec), Thieves’ Highway looks very good on this Blu-ray disc. The 35mm monochrome photography is crisp and with a strong level of fine detail present throughout, and it also displays some excellent contrast with very strong range within the mid-tones which shows off the film’s chiaroscuro photography. When Nick and Rica are out walking at night, for example, the light picks them up on the city streets like the spotlight on a stage, and around them the light fades off into deep shadow. It’s a big improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases, which displayed strong evidence of edge enhancement and digital sharpening. By contrast with those presentations, Arrow’s release has a pleasingly filmic look throughout, which is carried over by the characteristically superb encode that ensures the film has the organic grain structure one would expect from 35mm film. Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1 and in 1080p (using the AVC codec), Thieves’ Highway looks very good on this Blu-ray disc. The 35mm monochrome photography is crisp and with a strong level of fine detail present throughout, and it also displays some excellent contrast with very strong range within the mid-tones which shows off the film’s chiaroscuro photography. When Nick and Rica are out walking at night, for example, the light picks them up on the city streets like the spotlight on a stage, and around them the light fades off into deep shadow. It’s a big improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases, which displayed strong evidence of edge enhancement and digital sharpening. By contrast with those presentations, Arrow’s release has a pleasingly filmic look throughout, which is carried over by the characteristically superb encode that ensures the film has the organic grain structure one would expect from 35mm film.

NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented with an English LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich and resonant, displaying good range where it needs to (the rumble of trucks, for example). It’s accompanied by optional English subtitles.

Extras

The disc is housed in a case with reversible sleeve artwork and one of Arrow’s luscious booklets. The booklet for Thieves’ Highway includes a piece about the film by Alastair Phillips, who contributed to the BFI’s 100 Film Noirs book a few years ago. Phillips offers a good dissection of the film’s themes.  On the disc are: On the disc are:

- the documentary ‘The Long Haul of A I Bezzerides’ (2005) (55:42). This is the highlight of the contextual material on the disc. This documentary about the life and work of Bezzerides, which viewers have long been teased with by the inclusion of short clips from it on releases such as Criterion’s DVD/Blu-ray release of Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955) – an adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s novel which was scripted by Bezzerides – is finally available in its entirety. It’s a superb documentary which features readings from interviews with Bezzerides and impressionistic shots of the kinds of environments and situations about which his work revolved (trucks traveling through the American landscape, run-down truck stop cafes). The documentary features interviews with writers such as Barry Gifford, George Pelecanos and Mickey Spillane. These contributors attempt to get at the heart of what makes Bezzerides’ work tick. Gifford says Bezzerides ‘was writing about the common people’ but ‘he wasn’t filled with love of the common man at all’ and was ‘interested in the flaws of people [… and] the problems people made for themselves, and the temptations offered people’. Pelecanos talks about his first experiences of Bezzerides writing, arguing that Bezzerides’ depiction of the immigrant experience spoke to him. Pelecanos suggests ‘most American literature is about people who “win”’, but Bezzerides has a more ‘realistic’ focus within his literature – a characteristic that, Pelecanos suggests, separates run-of-the-mill literature from that which will be remembered by future generations. He says that he doesn’t think of Bezzerides’ work as noir but rather as ‘proletariat literature’. There are some newly-filmed interviews with Bezzerides, who talks in some detail about his working rituals (‘I keep typing until I’m too tired to go on any farther or until I’ve done what I want to do’). Bezzerides also discusses his school career, which was almost cut short by his father, who demanded Bezzerides work for him driving a truck. Bezzerides received ‘a slap you won’t believe’ when he told his father he wanted to go to college. In addition to these new interviews are some archival interviews with Bezzerides. In one of these, Bezzerides talks about the differences between adapting two of his novels, Thieves’ Market and The Long Haul, for the big screen. (These became Thieves’ Highway and They Drive By Night, respectively.) Bezzerides’ reflects on his script for Juke Girl (Curtis Bernhardt, 1942), which starred Ronald Reagan. ‘Reagan, I found out, was a very conservative guy’, Bezzerides quips. Bezzerides also talks about the original ending that he intended for Nicholas Ray’s On Dangerous Ground (1952). He argues that directors often overstate their importance, but ‘the fact is if the writer doesn’t do it, they [the director[ can’t do it’. Bezzerides ‘didn’t make friends out of motion picture people’ because he ‘kept myself separate from the congregation of people kissing ass in whatever situation they worked in. Writers have no business kissing ass’. Bezzerides and Spillane talk about the disdain they had for one another’s work: Bezzerides disliked Spillane’s novel Kiss Me Deadly intensely, and Spillane hated Bezzerides’ script for Robert Aldrich’s 1955 film adaptation of the novel. Bezzerides substituted the ‘junk’ within Spillane’s novel for the ‘Great Whatsit’ – one of the great metonyms for the terrors of the nuclear age. ‘I didn’t make it dope or nothing [….] I made it a nuclear device [….] And what do you know? Today it’s still in their minds’, Bezzerides boasts. Bezzerides’ love of photography is also examined in detail, with some examples of his photography presented for the viewer, and reflections by Bezzerides on the importance of photography in the films that he scripted. Illustrated with clips from films including Juke Girl, On Dangerous Ground and Kiss Me Deadly, this is a great documentary about an oft-neglected figure in American culture. It’s comparable in many ways (in terms of its structure and its production towards the end of its subject’s life) to Adam Simon’s brilliant Sam Fuller: The Typewriter, the Rifle and the Movie Camera (1996), and is almost worth the price of admission on its own. - ‘The Fruits of Labour’ (33:39). This is a newly-filmed interview with author Frank Krutnik, the writer of the book In a Lonely Street: Film Noir, Genre, Masculinity. Krutnik comments on the genesis of Thieves’ Highway and the contributions of both Bezzerides and Dassin towards the finished picture. He situates the film within the context of the bodies of work of both its writer and director, and highlights some of the major thematic motifs within the picture. It’s an interesting, well-researched and illuminating interview with an acknowledged expert within the field of film noir studies. - Commentaries by Frank Krutnik includes three sequences over which Krutnik provides scene-specific commentary. These sequences are: -- ‘The Homecoming’ (12:19), the sequence in which Nick returns home at the start of the picture; -- ‘Delicious Gold’ (7:48), the sequence in which Ed and Nick attempt to buy the Golden Delicious apples from the Polanskys; and -- ‘Rica’ (10:46), the sequence in which Rica attempts to seduce Nick and they come into conflict for the first time. - a stills gallery (0:42). - the film’s trailer (2:06).

Overall

Thieves’ Highway is a fantastic film, a gritty, street-level picture. Its rushed climax perhaps hampers it very slightly, but it’s certainly amongst the top tier of 1940s films noir – and, along with Brute Force, The Naked City and Night and the City, forms a part of a very strong run of films for Dassin – who, after the promise shown in Rififi, his first European picture, would end his career making much less interesting films in Europe. Thieves’ Highway is a fantastic film, a gritty, street-level picture. Its rushed climax perhaps hampers it very slightly, but it’s certainly amongst the top tier of 1940s films noir – and, along with Brute Force, The Naked City and Night and the City, forms a part of a very strong run of films for Dassin – who, after the promise shown in Rififi, his first European picture, would end his career making much less interesting films in Europe.

This presentation of Thieves’ Highway is very good, a big improvement over the previously-available DVDs, and contains some truly excellent contextual material – the most exciting of which is the long-awaited but long-withheld documentary about A I Bezzerides, whose claims to the authorship of this picture are arguably equal to those of Dassin. In all, it’s a superb package which, along with Arrow’s other releases of Dassin’s films, is not to be missed by a fan of films noir. References: Dewey, Donald, 2014: Lee J Cobb: Characters of an Actor. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Early, Emmett, 2014: The Alienated War Veteran in Film and Literature. London: McFarland and Company Gifford, Barry, 2001: Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir. University Press of Mississippi Lee, Daryl, 2014: The Heist Film: Stealing with Style. Chichester: Wallflower Press Naremore, James, 1998: More Than Night: Film Noir and Its Contexts. University of California Press Smith, Imogen Sara, 2011: In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City. London: McFarland and Company

|

|||||

|