|

The Film

Hellraiser: The Scarlet Box Hellraiser: The Scarlet Box

Hellraiser (Clive Barker, 1987)

Adapted from Clive Barker’s 1985 novella The Hellbound Heart and directed by the author himself, Hellraiser (1987) marked an audacious victory for British horror cinema, which had arguably been in the doldrums since the collapse of Hammer during the 1970s. Paul Wells notes that Barker ‘resurrected a notion of “British horror”’, something which had been ‘previously mainly understood as a phenomenon of Hammer Films […], the maverick talent Michael Reeves […] or exploitation auteurs like Pete Walker’ (Wells, 2002: 172). For Wells, Barker’s films reworked ‘the British horror tradition’ in a self-conscious manner, ‘simultaneously progress[ing] the tradition but also call[ing] attention to its neglected backwaters’ whilst at the same time ‘re-engag[ing]with the centrality of “Englishness” at the core of the genre’ (ibid.).

Where, with some notable exceptions, the British horror films of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s had tended to have historical settings and were very often rooted in acknowledged literary classics (for example, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Bram Stoker’s Dracula), Hellraiser was set very much in the present day and featured ‘Barker’s wholly invented demonology’ which ‘was truly unlike anything audiences had seen before’: the film’s ‘monsters’ were the Cenobites, led by the now iconic Pinhead, a group of creatures who valued the pleasure in pain and dressed in the garb of the sadomasochist (Golden et al, 2002: 72). Hellraiser shared with the Hammer horror films a focus on ‘monsters’, and like Hammer’s Frankenstein pictures Hellraiser depicted its monsters in a sympathetic way – something which would become Barker’s stock-in-trade in subsequent films, novels and screenplays such as Nightbreed (Clive Barker, 1990) and Candyman (Bernard Rose, 1992). However, although the first Hellraiser introduced the Cenobites and, in particular, the iconic Pinhead (Doug Bradley), Hellraiser itself is as much a ‘serial killer’ film as it is a traditional monster movie: the antagonist of the first film is really not Pinhead or the Cenobites but rather the very human Julia (Clare Higgins), who is acting under the orders of her resurrected lover Frank (Sean Chapman & Oliver Smith) to provide him with fresh sacrificial victims.

In a Middle Eastern city, Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) buys a mysterious puzzle box, the Lament Configuration, from a seller in a bazaar. We see Frank alone, ‘solving’ the puzzle box and opening a doorway to another world. Needles rip at his flesh. In the interior of the Cenobites’ realm, all shot through via blue chiaroscuro lighting, we see flayed flesh and body parts suspended via chains from the ceiling, as a Cenobite pieces together the torn fragments of a man’s face is if it were a jigsaw puzzle. In a Middle Eastern city, Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) buys a mysterious puzzle box, the Lament Configuration, from a seller in a bazaar. We see Frank alone, ‘solving’ the puzzle box and opening a doorway to another world. Needles rip at his flesh. In the interior of the Cenobites’ realm, all shot through via blue chiaroscuro lighting, we see flayed flesh and body parts suspended via chains from the ceiling, as a Cenobite pieces together the torn fragments of a man’s face is if it were a jigsaw puzzle.

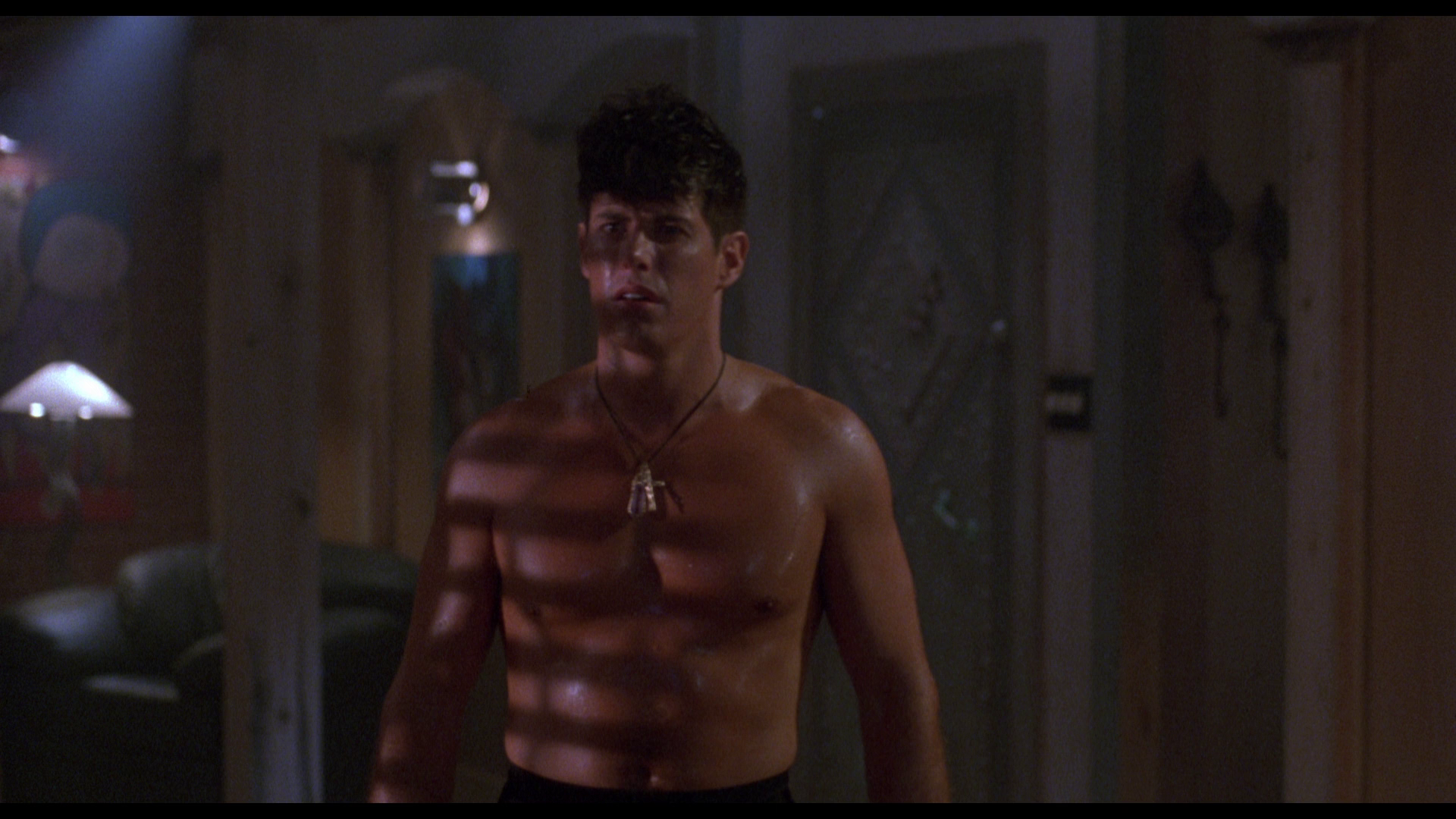

At Frank’s house (in England?), Frank’s brother Larry (Andy Robinson) and Larry’s wife Julia (Clare Higgins) arrive. They are moving in to the house, apparently against Julia’s desires. The house stirs old memories for Julia, who immediately prior to her marriage to Larry had a torrid affair with Frank. When Larry tears his hand on a nail whilst trying to lug a mattress through a doorway, he seeks aid from Julie. Larry is afraid of blood, and finding Julia in one of the empty rooms upstairs he spills his blood onto the floor. After the couple have left the room, the spilt blood acts as the agent which resurrects Frank. The skinless Frank (Oliver Smith) soon approaches Julia, asking her to help him. The kind of help Frank wants is for Julia to supply him with fresh victims whose blood will help Frank to regenerate.

Julia agrees to Frank’s request. She is reluctant at first but visibly begins to enjoy her work. She picks up men in bars and brings them back to the house, attacking and subduing them with a claw hammer before allowing Frank to ‘feed’ off them. Julia quickly becomes accustomed to the killing. However, Frank tells Julia that they only have a limited amount of time ‘before they start to follow [….] before they realise I’ve slipped them’. ‘They’ are the Cenobites, and as Frank tells Julia they may be summoned by solving the puzzle box, the Lament Configuration.

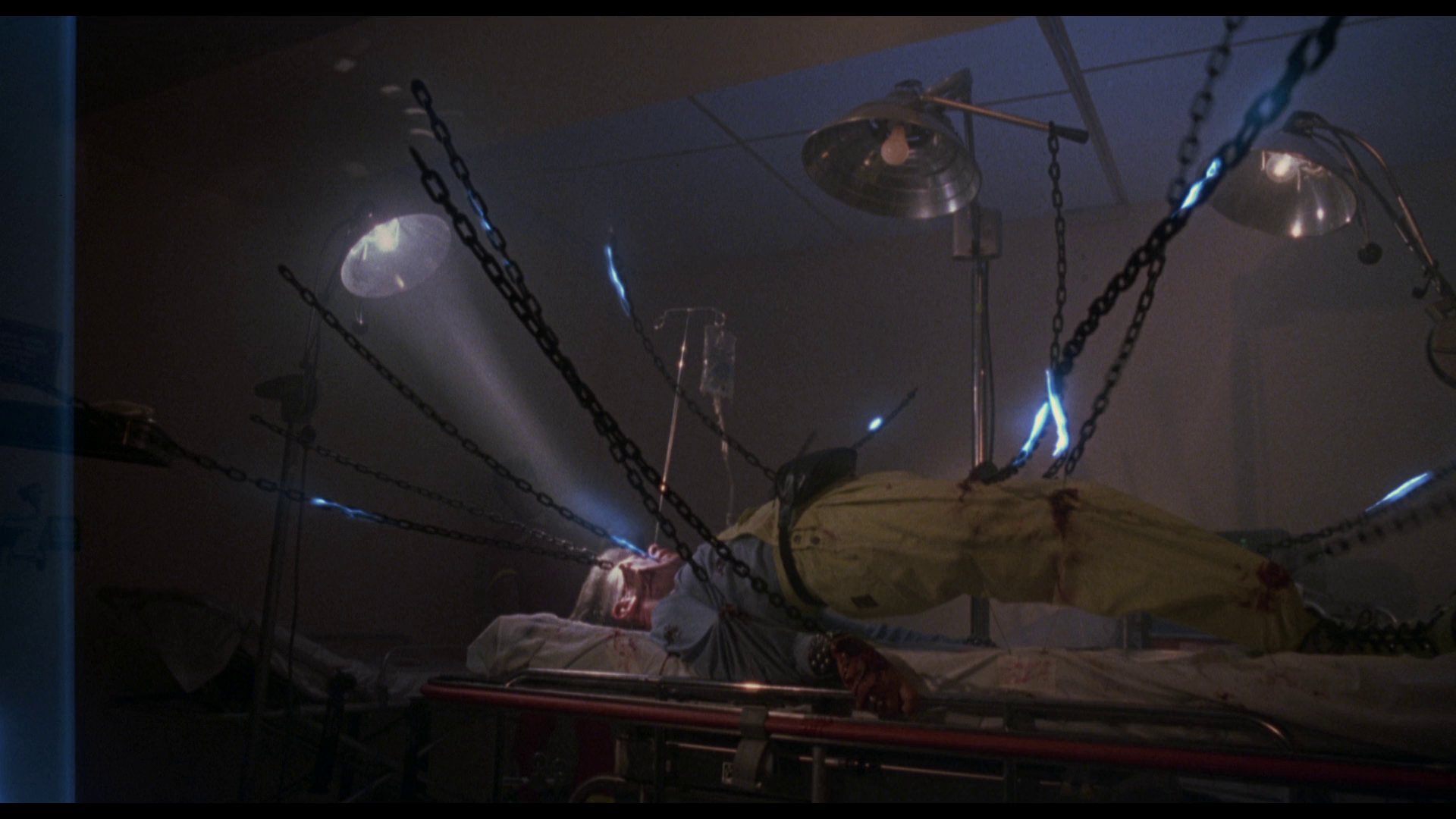

Paying a visit to her father, Kirsty encounters Frank, who tries to seduce her. Kirsty realises the importance of the Lament Configuration for her uncle and steals it, running away from the house. She awakens in the hospital. Toying with the puzzle box, she accidentally solves it, opening a door to the Cenobites’ world which opens onto her hospital room. Ridden with curiosity, Kirsty enters the portal and encounters a horrifying wall-crawling creature (known within the mythology surrounding the Hellraiser films and stories as ‘the Engineer’). This creature chases Kirsty back into her hospital room, where the Cenobites appear. Kirsty engages in dialogue with Pinhead, who only allows Kirsty to go free when Kirsty reveals that Frank has escaped from the Cenobites – and she can lead them to him. However, Kirsty is warned that if she attempts to betray the Cenobites they will ‘tear [her] soul apart’. Paying a visit to her father, Kirsty encounters Frank, who tries to seduce her. Kirsty realises the importance of the Lament Configuration for her uncle and steals it, running away from the house. She awakens in the hospital. Toying with the puzzle box, she accidentally solves it, opening a door to the Cenobites’ world which opens onto her hospital room. Ridden with curiosity, Kirsty enters the portal and encounters a horrifying wall-crawling creature (known within the mythology surrounding the Hellraiser films and stories as ‘the Engineer’). This creature chases Kirsty back into her hospital room, where the Cenobites appear. Kirsty engages in dialogue with Pinhead, who only allows Kirsty to go free when Kirsty reveals that Frank has escaped from the Cenobites – and she can lead them to him. However, Kirsty is warned that if she attempts to betray the Cenobites they will ‘tear [her] soul apart’.

Kirsty leads the Cenobites to the house Larry shares with Julia, but unbeknownst to Kirsty Frank has killed her father and is now wearing his skin. The Cenobites soon follow, but appear to have deceived Kirsty and try to claim both her and Frank.

From the outset, Frank’s absence in his own house is commented on by Julia and Larry, though Larry is unconcerned about his brother’s whereabouts. Walking through Frank’s house on their first arrival there, and referring to the clutter within the house, Larry promises Julia ‘this stuff all goes’. Amongst Frank’s belongings are bizarre religious artefacts (including a statue of a religious icon, adorned by garish red lights, holding a severed head – perhaps that of John the Baptist, though the exact context is unclear). ‘I thought this stuff was your brother’s’, Julia protests weakly. ‘I’ve never known Frank kick cash out of bed’, Larry tells her, highlighting his brother’s mercenary streak, ‘and besides he’s probably behind bars someplace’. Shortly afterwards, near Frank’s makeshift bed, Julia discovers an erotic statuette and pornographic Polaroids of the womanising Frank in flagrante delicto with his various female ‘conquests’. ‘Frank’s’, Larry laughs, ‘He’s obviously made one of his famous getaways’. However, Julia’s interest is piqued: she’s secretly fascinated by Frank’s private photographs, stealing one away and sneaking it into her jacket pocket.

Julia’s cold relationship with Kirsty is swiftly delineated when the removal men, bringing Larry and Julia’s belongings into Frank’s house, stare at Julia and then at Kirsty. ‘Is that your daughter?’, one of the removal men asks Larry, ‘Got her mother’s looks’. To this, Larry responds curtly: ‘Her mother’s dead’. The mention of Kirsty’s mother upsets Larry – that notion of upset delivered through Andy Robinson’s curt delivery of the line rather than through any specific content within the dialogue – and suggests that Larry has to some extent ‘settled for’ Julia. Within Hellraiser, family is a cold and potentially deceptive institution. Frank is willing to fuck his brother’s bride – and Julia is willing to betray her husband-to-be. At the housewarming party, Julia acts coldly towards her husband – even before she has become aware of the resurrected Frank’s presence in the house. Furthermore, the resurrected Frank seems willing to seduce Kirsty. Earlier in the film, Frank seduces Julia by saying ‘Come to daddy’; later, he uses the same command on Kirsty: ‘It’s Frank. It’s uncle Frank. You remember. Come to daddy’. The spilling of Larry’s blood is what causes Frank to be resurrected (‘His blood on the floor, it brought me back’, Frank tells Julia), leading Frank to demand that Julia help him by supplying him with fresh victims whose blood will facilitate his regenerative processes (‘The blood brought me this far. I need more. You have to heal me!’, Frank commands his former lover). Finally, this leads to Frank murdering Larry, and dressing in his flesh (like the wolf in ‘Little Red Cap’/‘Little Red Riding Hood’) in order to deceive Kirsty – thus betraying the only positive relationship within the film, that between Kirsty and her father, who aren’t particularly close but nevertheless display overt concern for one another’s welfare. Kirsty’s tip-off to the fact that Larry isn’t Larry at all but is rather Frank masquerading as Larry, is Frank’s repetition of the creepy line ‘Come to daddy’. At the climax of the film, as the Cenobites return for Frank, Julia and Kirsty, Frank’s house begins to crumble and collapse – like the House of Usher in Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, in which the collapse of the physical house is connected to the collapse of the family name under the weight of its secrets and inferred incest. Kirsty’s family, we may presume, has been consumed by the perverse desires of ‘uncle/brother Frank’. Julia’s cold relationship with Kirsty is swiftly delineated when the removal men, bringing Larry and Julia’s belongings into Frank’s house, stare at Julia and then at Kirsty. ‘Is that your daughter?’, one of the removal men asks Larry, ‘Got her mother’s looks’. To this, Larry responds curtly: ‘Her mother’s dead’. The mention of Kirsty’s mother upsets Larry – that notion of upset delivered through Andy Robinson’s curt delivery of the line rather than through any specific content within the dialogue – and suggests that Larry has to some extent ‘settled for’ Julia. Within Hellraiser, family is a cold and potentially deceptive institution. Frank is willing to fuck his brother’s bride – and Julia is willing to betray her husband-to-be. At the housewarming party, Julia acts coldly towards her husband – even before she has become aware of the resurrected Frank’s presence in the house. Furthermore, the resurrected Frank seems willing to seduce Kirsty. Earlier in the film, Frank seduces Julia by saying ‘Come to daddy’; later, he uses the same command on Kirsty: ‘It’s Frank. It’s uncle Frank. You remember. Come to daddy’. The spilling of Larry’s blood is what causes Frank to be resurrected (‘His blood on the floor, it brought me back’, Frank tells Julia), leading Frank to demand that Julia help him by supplying him with fresh victims whose blood will facilitate his regenerative processes (‘The blood brought me this far. I need more. You have to heal me!’, Frank commands his former lover). Finally, this leads to Frank murdering Larry, and dressing in his flesh (like the wolf in ‘Little Red Cap’/‘Little Red Riding Hood’) in order to deceive Kirsty – thus betraying the only positive relationship within the film, that between Kirsty and her father, who aren’t particularly close but nevertheless display overt concern for one another’s welfare. Kirsty’s tip-off to the fact that Larry isn’t Larry at all but is rather Frank masquerading as Larry, is Frank’s repetition of the creepy line ‘Come to daddy’. At the climax of the film, as the Cenobites return for Frank, Julia and Kirsty, Frank’s house begins to crumble and collapse – like the House of Usher in Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, in which the collapse of the physical house is connected to the collapse of the family name under the weight of its secrets and inferred incest. Kirsty’s family, we may presume, has been consumed by the perverse desires of ‘uncle/brother Frank’.

Moving into the house stirs erotic memories for Julia, who recollects her first meeting with Frank, during which he introduced himself at the doorway: ‘I’m Frank. I’m brother Frank. I came for the wedding’. Some nifty parallel editing ensues, cutting between the present (as Julia remembers her relationship with Frank, and Larry and the removal men attempt to lug a mattress through a doorway) and the past (Julia fucking Frank immediately prior to her marriage to Larry). Julia remembers Frank pulling out his flick knife and cutting the shoulder straps on her camisole (‘What about Larry?’, Julia asks. ‘Forget him’, Frank tells her, the blade of his knife springing out of its hilt), then fucking angrily. It’s clear that Frank represents for Julia the allure of the forbidden – the association of sexual excitement with the threat of violence. The aggressive thrusting of Frank and Julia’s sexual encounter coincides with the diegetic present and Larry’s grunting as he attempts to force the mattress through the doorway. As, in Julia’s memory, Frank and Julia reach their sexual climax, Larry tears his hand on a nail that sticks out of the doorframe, resulting in the spilling of his blood. The association of pain with the erotic, central to the Cenobites’ philosophy, is foregrounded through this audacious moment of symbolic montage. (Larry’s tearing of the flesh on the back of his hand could also be said to foreshadow what happens to him towards the climax of the picture.) As Frank says about the Lament Configuration, ‘It’s dangerous. It opens doors [….] Doors to the pleasures, heaven or hell. I didn’t care which. I thought I’d gone to the limits. I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible’. Later, Frank tells Julia, ‘Some things have to be endured, and that’s what makes the pleasure so sweet’. Moving into the house stirs erotic memories for Julia, who recollects her first meeting with Frank, during which he introduced himself at the doorway: ‘I’m Frank. I’m brother Frank. I came for the wedding’. Some nifty parallel editing ensues, cutting between the present (as Julia remembers her relationship with Frank, and Larry and the removal men attempt to lug a mattress through a doorway) and the past (Julia fucking Frank immediately prior to her marriage to Larry). Julia remembers Frank pulling out his flick knife and cutting the shoulder straps on her camisole (‘What about Larry?’, Julia asks. ‘Forget him’, Frank tells her, the blade of his knife springing out of its hilt), then fucking angrily. It’s clear that Frank represents for Julia the allure of the forbidden – the association of sexual excitement with the threat of violence. The aggressive thrusting of Frank and Julia’s sexual encounter coincides with the diegetic present and Larry’s grunting as he attempts to force the mattress through the doorway. As, in Julia’s memory, Frank and Julia reach their sexual climax, Larry tears his hand on a nail that sticks out of the doorframe, resulting in the spilling of his blood. The association of pain with the erotic, central to the Cenobites’ philosophy, is foregrounded through this audacious moment of symbolic montage. (Larry’s tearing of the flesh on the back of his hand could also be said to foreshadow what happens to him towards the climax of the picture.) As Frank says about the Lament Configuration, ‘It’s dangerous. It opens doors [….] Doors to the pleasures, heaven or hell. I didn’t care which. I thought I’d gone to the limits. I hadn’t. The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible’. Later, Frank tells Julia, ‘Some things have to be endured, and that’s what makes the pleasure so sweet’.

In Julia’s memory, she recalls a post-coital Frank complaining ‘It’s never enough’, suggesting he has a need or desire which can never be satiated. Meanwhile, in the diegetic present, Larry – who is afraid of blood – retreats upstairs, seeking Julia’s help in tending to his wound. ‘You know me and blood’, Larry complains in a childlike manner, ‘I’m going to faint’. Larry’s blood drops to the floor, in tight close-up, and we see it absorbed by the bare floorboards; the camera travels beneath the floorboards to reveal a cluster of cells growing beneath. Frank’s resurrection soon follows, away from the eyes of Julia and Larry. Fleshless, near-skeletal arms spring from the floorboard, then the curvature of Frank’s spine, and matter begins to form a brain and then a skull of sorts which attaches to the reborn Frank’s spine. Slowly, painfully, graphically, Frank is resurrected. His rebirth is in many ways very similar to the creation of the monster in the 1910 film version of Frankenstein (directed by J Searle Dawley). In that film, Frankenstein’s creation is born through alchemy in a pot within a sealed chamber. Like Frank in Hellraiser, the creature in the 1910 Frankenstein begins as a slowly-forming skeletal creature, muscle and tissue then forming on this skeleton. (In Frankenstein, this effect was achieved by burning a model of the monster and then reversing the footage.) The parallels between Hellraiser and the Frankenstein mythos would become even more apparent in Hellbound: Hellraiser II, in the relationship between Channard and the resurrected, bandage-clad Julia – which resembles that between Frankenstein and his female creation in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935). In Julia’s memory, she recalls a post-coital Frank complaining ‘It’s never enough’, suggesting he has a need or desire which can never be satiated. Meanwhile, in the diegetic present, Larry – who is afraid of blood – retreats upstairs, seeking Julia’s help in tending to his wound. ‘You know me and blood’, Larry complains in a childlike manner, ‘I’m going to faint’. Larry’s blood drops to the floor, in tight close-up, and we see it absorbed by the bare floorboards; the camera travels beneath the floorboards to reveal a cluster of cells growing beneath. Frank’s resurrection soon follows, away from the eyes of Julia and Larry. Fleshless, near-skeletal arms spring from the floorboard, then the curvature of Frank’s spine, and matter begins to form a brain and then a skull of sorts which attaches to the reborn Frank’s spine. Slowly, painfully, graphically, Frank is resurrected. His rebirth is in many ways very similar to the creation of the monster in the 1910 film version of Frankenstein (directed by J Searle Dawley). In that film, Frankenstein’s creation is born through alchemy in a pot within a sealed chamber. Like Frank in Hellraiser, the creature in the 1910 Frankenstein begins as a slowly-forming skeletal creature, muscle and tissue then forming on this skeleton. (In Frankenstein, this effect was achieved by burning a model of the monster and then reversing the footage.) The parallels between Hellraiser and the Frankenstein mythos would become even more apparent in Hellbound: Hellraiser II, in the relationship between Channard and the resurrected, bandage-clad Julia – which resembles that between Frankenstein and his female creation in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

The puzzle box is associated with the exotic. When Frank buys the box, we hear the Muslim call to prayer in the background and the heavily accented voice of the seller asks Frank, ‘What’s your pleasure, Mr Cotton?’ (‘The box’, is Frank’s pithy reply.) The photography emphasises the heat of the setting: the sweat on Frank’s forearm as he makes the exchange, paying for the box in American dollars. The faces of both Frank and the seller are in strong, deep shadow, giving their transaction a sense of mystery and intrigue. ‘Take it. It’s yours. It always was’, the seller tells Frank, his words conveying a sense of fatalism: that Frank, like all those drawn to the box, is destined to his own personal hell. Frank’s fingernails, we notice as he puts the money on the table in close-up, are filthy; in the background, a fly – a creature associated with decay – buzzes loudly. This is an auditory motif which recurs later in the film. When Larry and Julia move into Frank’s house, the soundscape is once again dominated by the buzzing of flies – suggesting the decay that is readily apparent within the mise-en-scène (rotting food on plates with cigarette butts) but also connecting this space, Frank’s house in which Frank will be resurrected by his brother’s blood, to the exotic locale in which Frank purchased the box. In Frank’s house, a birdcage – which, given Larry’s response after lifting the sheet which covers it, presumably holds a dead domestic bird – hangs via a chain from the ceiling in the living room, metonymically connecting Frank’s home to the interior chambers associated with the Cenobites (in which various body parts are shown hanging from chains).

The box, when solved, opens a doorway to the world of the Cenobites – a world which will be fleshed out more thoroughly in the secrets, but within the context of Hellraiser remains largely mysterious. Kirsty’s opening of the box summons the Cenobites. ‘The box. You opened it. We came’, Pinhead tells Kirsty upon their first meeting in the hotel room. ‘It’s just a puzzle box!’, Kirsty protests. ‘Oh, no’, Pinhead tells her, ‘It is a means to summon us’. ‘Who are you?’, Kirsty asks. ‘Explorers in the further regions of experience’, Pinhead answers, ‘Demons tot some; angels to others. You solved the box; we came. Now you must come with us; taste our pleasures’. Recognising Kirsty’s fear, Pinhead tells her, ‘Oh, no tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering’. The box, when solved, opens a doorway to the world of the Cenobites – a world which will be fleshed out more thoroughly in the secrets, but within the context of Hellraiser remains largely mysterious. Kirsty’s opening of the box summons the Cenobites. ‘The box. You opened it. We came’, Pinhead tells Kirsty upon their first meeting in the hotel room. ‘It’s just a puzzle box!’, Kirsty protests. ‘Oh, no’, Pinhead tells her, ‘It is a means to summon us’. ‘Who are you?’, Kirsty asks. ‘Explorers in the further regions of experience’, Pinhead answers, ‘Demons tot some; angels to others. You solved the box; we came. Now you must come with us; taste our pleasures’. Recognising Kirsty’s fear, Pinhead tells her, ‘Oh, no tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering’.

The most frightening scenes of the film are perhaps those in which Julia cruises for her victims and brings them back to Frank’s house, where they will meet their fate. Upon entering the house, Julia’s first victim expresses his anxiety about the situation. ‘There’s a first time for everything’, Julia tells him; the man is of course unaware of the double meaning within Julia’s statement (that this represents Julia’s first time in committing murder, rather than her first time fucking a stranger). The victims aren’t particularly sympathetic: when Julia expresses some anxiety about what she’s doing – unbeknownst to the man, questioning her contract with Frank – one of the men responds angrily, threatening Julia with violence before backing down and apologising. Nevertheless, the deaths of Julia’s victims are horrifying. Julia leads them into Frank’s bare, carpetless room and reaches for a claw hammer that is pinned behind the door. Her first victim begs, ‘Please! Please!’ as she hits him with the hammer several times, the blood splashing across her clothes and face. (This scene was a sticking point for the BBFC when Hellraiser was originally submitted for home video classification, with the BBFC cutting the shot of the victim pressing his hands to his wounded mouth and begging ‘Please! Please!’) Following this, Frank is shown gruesomely ‘feeding’ off the corpses: ‘See? It’s making me whole again’, Frank tells Julia, ‘Every drop of blood you spill puts more flesh on my bones, and we both want that, don’t we?’ The domestic/suburban setting, and the use of an unspectacular hammer as a murder weapon, ensures the film has echoes of the popularity of fiction about serial killers during the 1980s.

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Tony Randel, 1988) Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Tony Randel, 1988)

Where the Cenobites are in the background for much of Hellraiser, they are pushed front-and-centre for the narrative of Hellbound: Hellraiser II. The general consensus has it that the Hellraiser sequels validated the concept of the law of diminishing returns. David Sanjek suggests that where Barker’s Hellraiser ‘brought up some genuinely troubling and provocative questions about the possibility of transcendence through pain and sadomasochism-driven relationships’, its sequels ‘abandoned thoughtful inquiry by and large for splatter and special effects, so far as the ratings board permitted’ (Sanjek, 2000: 112).

Hellbound: Hellraiser II opens with Elliott Spencer’s (Doug Bradley) encounter with the Lament Configuration. Spencer is shown in a historical setting, presumably North Africa or the Middle East at some point between the two world wars, as he solves the puzzle box. It is an encounter which leads to Spencer’s transformation into Pinhead, depicted graphically on screen.

Following this, we are taken to the present day, immediately after the events in the first film, where Kirsty is incarcerated in a mental hospital. The hospital is presided over by Dr Channard (Kenneth Cranham), who takes a little too much pleasure in the invasive brain surgery he is seen practising in the scene that introduces him. Kirsty is interviewed by a police detective, Ronson (Angus MacInnes), about the deaths of Julia and Larry. Ronson disbelieves Kirsty’s story about what transpired in the house: ‘And this time, no demon fairytales, huh?’, he tells her; to this, Kirsty responds, ‘My father didn’t believe in fairytales either, Mr Ronson [….] Some of them come true. Even the bad ones’.

A young doctor, Kyle (William Hope), begins to believe Kirsty’s story and promises to help her escape. Meanwhile, Kirsty is introduced to the young girl in the room next to her’s, Tiffany (Imogen Boorman). Tiffany hasn’t spoken a word since the death of her mother, but is a natural at solving puzzles. Kyle suggests to Kirsty that ‘Channard thinks it may be a good thing’: that by solving the puzzles, Tiffany is ‘putting something in order’. ‘Or opening doors’, Kirsty suggests. A young doctor, Kyle (William Hope), begins to believe Kirsty’s story and promises to help her escape. Meanwhile, Kirsty is introduced to the young girl in the room next to her’s, Tiffany (Imogen Boorman). Tiffany hasn’t spoken a word since the death of her mother, but is a natural at solving puzzles. Kyle suggests to Kirsty that ‘Channard thinks it may be a good thing’: that by solving the puzzles, Tiffany is ‘putting something in order’. ‘Or opening doors’, Kirsty suggests.

Kyle gives Kirsty a sedative to put her to sleep. During this, Kirsty experiences a horrifying vision: a flayed corpse, apparently that of her father, writing on the wall in its own blood the phrase ‘I AM IN HELL. HELP ME’. Hearing that Channard has had the blood-stained mattress from Larry and Julia’s house delivered to Channard’s own home, Kyle breaks into Channard’s house to investigate. There, he finds paraphernalia relating to the Cenobites, and watches from a hiding place as Channard brings one of the hospital’s patients into the room and oversees a bizarre ritual which results in the shedding of the patient’s blood and the resurrection of Julia.

As Kyle arranges for Kirsty’s escape from the hospital, Channard brings a number of patients back to his house as victims for Julia. When Kyle encounters Julia, he is killed by her. Meanwhile, Kirsty discovers the paperwork Channard possesses on Elliott Spencer and the Lament Configuration. She is confronted by Julia (‘They didn’t tell you, did they, Kirsty? They changed the rules of the fairytale. I’m no longer the wicked stepmother: I’m the evil queen. So come on, take your best shot, Snow White!’) and discovers that Channard has brought Tiffany from the hospital with the intention that, using her innate puzzle-solving ability, she will ‘open’ the Lament Configuration.

Tiffany is successful. The puzzle box is opened; the Cenobites arrive. Channard and Julia enter the portal, as do Kirsty and Tiffany. There, Kirsty finds herself once again confronted by Pinhead and his Cenobites. (‘Oh, Kirsty. So eager to play; so reluctant to admit it’, Pinhead says, ‘Please feel free to explore. We have eternity to know your flesh’.) Led to Leviathan by Julia, in a gruesome sequence Channard is turned into a Cenobite. Amidst this, Kirsty and Tiffany must escape from the labyrinth and attempt to use the puzzle box to close the door to the netherworld for good. Tiffany is successful. The puzzle box is opened; the Cenobites arrive. Channard and Julia enter the portal, as do Kirsty and Tiffany. There, Kirsty finds herself once again confronted by Pinhead and his Cenobites. (‘Oh, Kirsty. So eager to play; so reluctant to admit it’, Pinhead says, ‘Please feel free to explore. We have eternity to know your flesh’.) Led to Leviathan by Julia, in a gruesome sequence Channard is turned into a Cenobite. Amidst this, Kirsty and Tiffany must escape from the labyrinth and attempt to use the puzzle box to close the door to the netherworld for good.

Through the character of Channard, and his reign over the mental hospital, Hellbound: Hellraiser II seems to offer an anti-psychiatry perspective to rival that of R D Laing. (This seems compounded in Barker’s Nightbreed, 1990, the film that Barker loosened his grip on the reins of the Hellraiser sequel in order to direct.) The film’s depiction of the mental hospital as a place of repression – where Kirsty is confined owing to the perception that her version of events cannot possibly be true and therefore must be suppressed – depicts psychiatry as having progressed little, if at all, since the Victorian era. This sense of psychiatry being stunted is partly communicated through the film’s mise-en-scène and the depiction of Channard’s psychiatric institution as existing within an old Nineteenth Century building. It’s a depiction of a mental hospital that differs little from that of Mark Robson’s Bedlam (1946).

Channard is introduced performing invasive brain surgery on one of the patients at the hospital. He lords over the room, delivering a monologue as he drills into the patient’s skull – an action which is mirrored later in the film when Leviathan, choosing to make a Cenobite of Channard, opts to have a device drill into Channard’s skull and carry his body, thus allowing the Channard Cenobite to float above the ground. During the moment of brain surgery, Channard declares that ‘The mind is a labyrinth, ladies and gentlemen; a puzzle. While the paths of the brain are plainly visible […] its destinations are unknown, its secrets still secret. And, if we are honest, it is the lure of the labyrinth that draws us to our chosen field, to unlock these secrets’. Channard’s monologue ends by drawing fairly explicit comparisons between his rhetoric and that of the Nazis: Channard concludes by asserting that he and his colleagues must go further than their predecessors in the hope of finding ‘ultimately, the final solution’. Channard’s suggestion that the ‘mind is a labyrinth’ also implies that the journey into Leviathan’s labyrinth later in the picture is, for the characters, also a journey into themselves. This is certainly true for Tiffany, who enters the portal opened by the puzzle box to be confronted with some incredibly bizarre, nightmarish imagery: her mother’s murder, which she witnessed and which is the root of her lack of willingness to speak; and a strange image of a clown juggling with his own eyeballs, which have been plucked out of his head. Likewise, when Leviathan’s dark beam – which reveals the sin and desire within those whom it touches – passes over Channard, the audience is presented with a montage of Channard’s memories which depict him as a young boy dissecting a small animal in a red room. Channard is introduced performing invasive brain surgery on one of the patients at the hospital. He lords over the room, delivering a monologue as he drills into the patient’s skull – an action which is mirrored later in the film when Leviathan, choosing to make a Cenobite of Channard, opts to have a device drill into Channard’s skull and carry his body, thus allowing the Channard Cenobite to float above the ground. During the moment of brain surgery, Channard declares that ‘The mind is a labyrinth, ladies and gentlemen; a puzzle. While the paths of the brain are plainly visible […] its destinations are unknown, its secrets still secret. And, if we are honest, it is the lure of the labyrinth that draws us to our chosen field, to unlock these secrets’. Channard’s monologue ends by drawing fairly explicit comparisons between his rhetoric and that of the Nazis: Channard concludes by asserting that he and his colleagues must go further than their predecessors in the hope of finding ‘ultimately, the final solution’. Channard’s suggestion that the ‘mind is a labyrinth’ also implies that the journey into Leviathan’s labyrinth later in the picture is, for the characters, also a journey into themselves. This is certainly true for Tiffany, who enters the portal opened by the puzzle box to be confronted with some incredibly bizarre, nightmarish imagery: her mother’s murder, which she witnessed and which is the root of her lack of willingness to speak; and a strange image of a clown juggling with his own eyeballs, which have been plucked out of his head. Likewise, when Leviathan’s dark beam – which reveals the sin and desire within those whom it touches – passes over Channard, the audience is presented with a montage of Channard’s memories which depict him as a young boy dissecting a small animal in a red room.

Of course, it is soon revealed that Channard is using the hospital and its patients to pursue his own peccadilloes. Channard has the blood-stained mattress on which Julia died shipped to his house. When Kyle breaks into Channard’s house to investigate the delivery of this bizarre item, Kyle discovers that Channard has a room dedicated to items associated with the Cenobites: three copies of the Lament Configuration, and a folder of photographs and notes detailing the life of Elliott Spencer. Kyle hides in the room and bears witness to the bizarre ritual enacted by Channard in the hopes of connecting with the otherworld in which the Cenobites exist. Piecing together elements from Kirsty’s story, Channard has a patient suffering from paranoid delusions brought to the house. The patient is suffers from the very specific delusion that insects are crawling over and through his skin. Channard allows the patient to sit on the mattress, undoes his restraints and passes him a straight razor. The patient uses the razor to mutilate himself, in the hopes of ridding himself of the imagined insects, and spills his blood on the mattress. Channard thus facilitates the patient’s desire to self-harm for his own esoteric purposes; this causes the resurrection of Julia, who emerges from the blood-soaked mattress to ‘consume’ the patient. Channard then uses his authority within the hospital to acquire further patients, who he then uses as victims for Julia to consume.

Channard’s paternalistic philosophy is outlined early in the film, through his declaration to his colleagues, in reference to patients such as Kirsty, that ‘We must win from them their trust, draw from them their stories, and take from them their pain’. When, later in the film, Kirsty asks Channard if he believes her story, ‘Am I crazy?’, Channard responds with the evasive diplomacy associated with his profession: ‘That is a not a word we choose to employ, Kirsty’. Channard’s transformation into a Cenobite results in a bizarre, topsy-turvy parody of his work in the mental hospital. Believing herself to have escaped from the labyrinth, Kirsty stumbles into a ward within the hospital, filled with beds containing a number of patients. However, Kirsty soon realises that this is simply an extension of the labyrinth: it’s a bizarre hell, a parody of medicine, that is presided over by the Channard Cenobite. ‘The doctor is in’, the Channard Cenobite declares as he enters the room, chuckling. ‘I recommend… amputation’, he asserts before using his new appendages to remove the limbs of the patients in the ward in the manner of a spiteful child who tears the wings from a fly. Channard’s paternalistic philosophy is outlined early in the film, through his declaration to his colleagues, in reference to patients such as Kirsty, that ‘We must win from them their trust, draw from them their stories, and take from them their pain’. When, later in the film, Kirsty asks Channard if he believes her story, ‘Am I crazy?’, Channard responds with the evasive diplomacy associated with his profession: ‘That is a not a word we choose to employ, Kirsty’. Channard’s transformation into a Cenobite results in a bizarre, topsy-turvy parody of his work in the mental hospital. Believing herself to have escaped from the labyrinth, Kirsty stumbles into a ward within the hospital, filled with beds containing a number of patients. However, Kirsty soon realises that this is simply an extension of the labyrinth: it’s a bizarre hell, a parody of medicine, that is presided over by the Channard Cenobite. ‘The doctor is in’, the Channard Cenobite declares as he enters the room, chuckling. ‘I recommend… amputation’, he asserts before using his new appendages to remove the limbs of the patients in the ward in the manner of a spiteful child who tears the wings from a fly.

As Christopher Sharrett has noted, Hellraiser offers a reworking of the myth of Pandora’s Box ‘and the Eve narrative […] by putting human destiny squarely in the hands of the capricious and too-curious female’ (Sharrett, 2015: 290). Hellbound: Hellraiser II expands on this mythos, fleshing out (so to speak) the netherworld which is opened up by the puzzle box, the Lament Configuration. In Hellbound: Hellraiser II successful navigation of the puzzle box opens up the world of the labyrinth, which is ruled over by Leviathan. Hellbound: Hellraiser II’s narrative makes it clear that Leviathan is ‘the god of flesh, hunger and desire’ (in the words of Julia), able to transform his shape (and that of the Lament Configuration) from a cube to an octrahedron; Leviathan is also the creator of the Cenobites, who are his acolytes. Leviathan’s ‘geometic diamond shape, its steely hardness, and its industrial machinelike appearance contrast sharply against those weak, disorderly, fleshy human subjects. Indeed, the apparently impenetrable hardness’ of Leviathan ‘exposes what everyone else lacks and desires’ (Beal, 2002: 100). Leviathan ‘does so in the most physical way, by messing with their skin’, peeling it away to reveal ‘the soft vulnerable flesh inside’ (ibid.). The name ‘Leviathan’ is an ancient one, referenced in the Old Testament and also alluded to in a number of other religions. The seventeenth century thinker Thomas Hobbes used the name ‘Leviathan’ as the title of his 1651 book which proposed the notion of ‘absolute’ government as a means of maintaining social order. The god/demon Leviathan, a ‘monster of political hegemony’ offers this stability over the world of the labyrinth (ibid.); the disruption to this system of order that is represented through the conflict between Pinhead’s group of Cenobites and Leviathan’s newest Cenobite, Channard, results in instability within the labyrinth. Ultimately, Leviathan ‘is not a monstrous figure of chaos but a monstrous figure of order’ and of hegemony (ibid.: 101).

Speaking of Pinhead himself, Sharrett has connected ‘his aristocratic bearing, his ability to rejuvenate himself (the return of the repressed), and his control of the “primal horde”’ with the mythology surrounding Dracula, but on the other hand Pinhead’s ‘grotesque, sadomasochistic aspect speaks to the media representation of postpunk nihilism that debunks the romance of transgression and resistance’ (Sharrett, op cit.: 290). Vampirism is referenced in the ways in which the resurrected Frank and the resurrected Julia regenerate themselves in, respectively, Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II. In the first film, Frank persuades Julia to bring him fresh victims, and Julia picks up men in bars, returning them to the house where she subdues them with a claw hammer. She then leaves the men in the room with Frank, who buries his fingertips into their skull and absorbs whatever material he needs to regenerate his skin and muscle tissue. It’s a form of vampirism, different to the neck-biting, fanged aristocratic vampires that have become most commonly associated with the idea of the vampire owing to their representation in popular films (for example, the Tod Browning Dracula of 1931), but closer to the notion of revenants in the folklore of the middle ages – creatures which returned from the grave to torment former family members and friends, and which gradually evolved into the modern mythology of the vampire. In Hellbound: Hellraiser II, Julia is resurrected as one of these revenants by Channard, in a ritual which involves Channard enabling one of his patients – who has delusions that beetles are crawling on his skin – to slash his torso with a straight razor on the mattress on which Julia died. This, of course, causes Julia to return to the land of the living. Channard clads her fleshless frame in bandages, and Julia persuades Channard to find him victims – which Julia dispatches in the same way Frank did in Hellraiser. Julia takes as one of her victims Kyle, the young doctor who rescues Kirsty from the institution in which she has been incarcerated; Julia kisses Kyle whilst burying her fingertips in his skull. Kyle’s veins pop and his skin takes on the dessicated appearance of a corpse. The iconography here (Julia’s kiss; Kyle’s rapid degeneration) recalls that of Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce (1985), in which the ‘space vampires’ absorb their victims’ ‘lifeforce’ via a kiss. Speaking of Pinhead himself, Sharrett has connected ‘his aristocratic bearing, his ability to rejuvenate himself (the return of the repressed), and his control of the “primal horde”’ with the mythology surrounding Dracula, but on the other hand Pinhead’s ‘grotesque, sadomasochistic aspect speaks to the media representation of postpunk nihilism that debunks the romance of transgression and resistance’ (Sharrett, op cit.: 290). Vampirism is referenced in the ways in which the resurrected Frank and the resurrected Julia regenerate themselves in, respectively, Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II. In the first film, Frank persuades Julia to bring him fresh victims, and Julia picks up men in bars, returning them to the house where she subdues them with a claw hammer. She then leaves the men in the room with Frank, who buries his fingertips into their skull and absorbs whatever material he needs to regenerate his skin and muscle tissue. It’s a form of vampirism, different to the neck-biting, fanged aristocratic vampires that have become most commonly associated with the idea of the vampire owing to their representation in popular films (for example, the Tod Browning Dracula of 1931), but closer to the notion of revenants in the folklore of the middle ages – creatures which returned from the grave to torment former family members and friends, and which gradually evolved into the modern mythology of the vampire. In Hellbound: Hellraiser II, Julia is resurrected as one of these revenants by Channard, in a ritual which involves Channard enabling one of his patients – who has delusions that beetles are crawling on his skin – to slash his torso with a straight razor on the mattress on which Julia died. This, of course, causes Julia to return to the land of the living. Channard clads her fleshless frame in bandages, and Julia persuades Channard to find him victims – which Julia dispatches in the same way Frank did in Hellraiser. Julia takes as one of her victims Kyle, the young doctor who rescues Kirsty from the institution in which she has been incarcerated; Julia kisses Kyle whilst burying her fingertips in his skull. Kyle’s veins pop and his skin takes on the dessicated appearance of a corpse. The iconography here (Julia’s kiss; Kyle’s rapid degeneration) recalls that of Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce (1985), in which the ‘space vampires’ absorb their victims’ ‘lifeforce’ via a kiss.

Interviewed by Paul Wells, Barker has reflected on one of his major dislikes within modern fantasy fiction, which is its tendency to be ‘either so epic in scope that the world described is beyond my power to identify with it […] or else, so small-scale, so domestic […] that the fantastical elements are reduced by association’ (Barker, quoted in Wells, op cit.: 175). Barker suggests that what he tries to do with his fiction is find ‘a middle area […] in which you begin with the domestic and then open out the vistas’ (Barker, quoted in ibid.). This is certainly true of Hellraiser, which begins in a domestic setting but then opens this up via the device of the puzzle box. Hellbound: Hellraiser II follows a similar structure, beginning its narrative in a recognisable environment (the mental hospital) before again using the Lament Configuration to ‘open up’ the narrative to include the netherworld and the labyrinth over which Leviathan presides. This paradigm – the juxtaposition of the ‘real’ world with a more fantastical one – allies both Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II with the fantasy films of the 1980s (for example, Wolfgang Petersen’s The NeverEnding Story, 1984) as much as with many contemporaneous horror pictures. Interviewed by Paul Wells, Barker has reflected on one of his major dislikes within modern fantasy fiction, which is its tendency to be ‘either so epic in scope that the world described is beyond my power to identify with it […] or else, so small-scale, so domestic […] that the fantastical elements are reduced by association’ (Barker, quoted in Wells, op cit.: 175). Barker suggests that what he tries to do with his fiction is find ‘a middle area […] in which you begin with the domestic and then open out the vistas’ (Barker, quoted in ibid.). This is certainly true of Hellraiser, which begins in a domestic setting but then opens this up via the device of the puzzle box. Hellbound: Hellraiser II follows a similar structure, beginning its narrative in a recognisable environment (the mental hospital) before again using the Lament Configuration to ‘open up’ the narrative to include the netherworld and the labyrinth over which Leviathan presides. This paradigm – the juxtaposition of the ‘real’ world with a more fantastical one – allies both Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II with the fantasy films of the 1980s (for example, Wolfgang Petersen’s The NeverEnding Story, 1984) as much as with many contemporaneous horror pictures.

The influx of American money into Hellraiser brought with it a stipulation that the film should be more ‘friendly’ to American audiences. Barker had already included a tip of the hat in this direction by making a number of the characters (chiefly, Larry and Kirsty) American, but New World Pictures encouraged Barker to redub the characters of Frank and Steve with American accents too. However, the number of British supporting players (for example, the removal men and Julia’s victims) and certain elements of iconography which ‘anchor’ the film’s location (for example, British Railways trains seen in the background) suggest that the story of Hellraiser takes place in Britain. This sense of geography becomes increasingly confused, however, in Hellbound: Hellraiser II, which from the outset seems to take place in America: the police who are seen investigating Larry and Julia’s house, for example, are clearly American policemen. Anthony Hickox’s Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992) continues this trend, featuring a very overtly American setting in a film that was the first Hellraiser picture to be shot outside the UK.

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Anthony Hickox, 1992) Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Anthony Hickox, 1992)

In an American city, young nightclub owner J P Monroe (Kevin Bernhardt) enters the Pyramid Gallery and buys a sculpture for his club, The Boiler Room. Unbeknownst to Monroe, the sculpture is in fact the Pillar of Souls and contains the trapped Pinhead and the Lament Configuration. Pinhead awaits a blood sacrifice that will allow him to escape from his temporary prison.

Meanwhile, Joey (Terry Farrell), a female television news reporter, is covering a story in a hospital when a new patient is rushed into the building following an incident at The Boiler Room. The new patient’s body has chains attached to it. He’s rushed into a room for emergency treatment but his head explodes. Joey witnesses this bizarre scene and, the next day, proposes that her crew cover it; however, she is told simply, ‘This is TV. No pictures, no story’.

Eager to investigate the story in her own time, Joey visits The Boiler Room. Joey approaches Monroe but he gives her the brush off. Joey manages to speak with Monroe’s former lover and an acquaintance of Joey’s, Terri (Paula Marshall). Terri tells Joey that the young man who died was hit by chains that she claims ‘came out of this’ – and with that, Terri passes to Joey what appears to be a sculpture of the Lament Configuration (but which in fact contains the real puzzle box).

Terri tells Joey about Monroe’s ‘really weird statue’ and takes Joey to the Pyramid Gallery where Monroe bought the Pillar of Souls. However, the gallery is closed and has been for some time. Joey breaks into the gallery and finds paperwork which suggests that the Pillar of Souls was bought from the Channard Institute.

Meanwhile, in his apartment above The Boiler Room, Monroe enjoys a one night stand with a girl from the club downstairs before cruelly dismissing her. The girl backs towards the Pillar of Souls and is attacked by Pinhead: the Pillar of Souls shoots out chains which attach themselves by hooks to the girl’s flesh. Pinhead absorbs the girl and enlists Monroe’s help in bringing him more victims whose power he can absorb in order to break free from his prison. Monroe calls Terri to his apartment and attempts to set her up as a victim for Pinhead. However, Terri turns the tables on Monroe and Pinhead sinks his hooks and chains into the flesh of Monroe instead. Meanwhile, in his apartment above The Boiler Room, Monroe enjoys a one night stand with a girl from the club downstairs before cruelly dismissing her. The girl backs towards the Pillar of Souls and is attacked by Pinhead: the Pillar of Souls shoots out chains which attach themselves by hooks to the girl’s flesh. Pinhead absorbs the girl and enlists Monroe’s help in bringing him more victims whose power he can absorb in order to break free from his prison. Monroe calls Terri to his apartment and attempts to set her up as a victim for Pinhead. However, Terri turns the tables on Monroe and Pinhead sinks his hooks and chains into the flesh of Monroe instead.

Joey experiences visions involving her father, who was killed during the Vietnam War; these become conflated with visions of the trenches in the First World War, where Joey meets Captain Elliott Spencer. Spencer is a British officer, the man who became Pinhead upon solving the Lament Configuration. Monroe enlists Joey’s help in using the Lament Configuration to set a trap for Pinhead, though Monroe warns Joey that Pinhead will seek to destroy the box.

Hellbound: Hellraiser II expands on the mythos introduced in Hellraiser, focusing on the human origins of the Cenobites. This duality of identity, between the human and Cenobite became the abiding focus of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, in which Pinhead is confronted by his human alter-ego, Captain Elliott Spencer. Christopher Sharrett suggests that in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, Pinhead acquires a ‘superstar centrality’ which ‘valorizes rather typically the monster-as-hero’ (Sharrett, op cit.: 291). Doug Bradley has claimed that Barker told Bradley to think of Pinhead as ‘some lowly clerk in a corporation’, and when Bradley put on the Pinhead makeup and looked in the mirror he was struck with ‘a deep sense of melancholia in the face, powerful and unsettling’ (Bradley, quoted in Kane, 2006: 91). Part of this sense of melancholy was communicated through ‘[t]he layout of the nails being symmetrical […] It was clearly something that was done to him. The melancholy showed me he was human, once. He was, in a way he could not express, mourning the loss of his humanity’ (Bradley, quoted in ibid.). The climax of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth leads to a battle of wills between Spencer and Pinhead which employs some ugly-looking CGI morphing effects and might make the viewer think of the climactic ‘mind battle’ between telepath brothers Darryl Revok (Michael Ironside) and Cameron Vale (Stephen Lack) in David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981).

Paul Wells argues that in Hellraiser, Barker ‘uses the theme of sado-masochism not merely to draw together the issues of eroticism and brutality, but to emphasise the protean nature of the body and identity’: the horror within the Hellraiser films (as well as Nightbreed) originates in ‘the fear of a perverse yet partially desired experience of marginalized or unknown “otherness”’ (Wells, op cit.: 172). Pinhead’s appearance represents ‘an act of controlled brutality that results in an aesthetically pleasing yet perverse beauty’ (ibid.: 173). Yet Pinhead’s cruelty is matched by that of some of the film’s human characters, who arguably offset Pinhead’s status as the film’s chief villain. Paul Wells argues that in Hellraiser, Barker ‘uses the theme of sado-masochism not merely to draw together the issues of eroticism and brutality, but to emphasise the protean nature of the body and identity’: the horror within the Hellraiser films (as well as Nightbreed) originates in ‘the fear of a perverse yet partially desired experience of marginalized or unknown “otherness”’ (Wells, op cit.: 172). Pinhead’s appearance represents ‘an act of controlled brutality that results in an aesthetically pleasing yet perverse beauty’ (ibid.: 173). Yet Pinhead’s cruelty is matched by that of some of the film’s human characters, who arguably offset Pinhead’s status as the film’s chief villain.

Monroe’s cruelty is established early on and framed within the same terms as Pinhead’s ‘consumption’ of one of his victims, suggesting a cycle of patriarchal/misogynistic violence which is offset by the film’s focus on a female protagonist. Monroe fucks a girl from the nightclub in his room upstairs, in front of the Pillar of Souls and watched (unbeknownst to Monroe) by the trapped Pinhead. After he has had his way with the girl, Monroe dismisses her sharply. She tries to make conversation about some of the macabre art that decorates his apartment, but Monroe cuts her off impolitely. ‘Who do you think you are?’, the girl asks. ‘I’m J P Monroe, bitch’, Monroe answers her, ‘Now give me back my shirt and get the fuck out of my life’. The girl challenges Monroe’s attitude: ‘You think you’re some goddamn prince or something, with your shitty little kingdom out there and all this ugly shit?’ Pinhead reacts to this, shooting out chains from the Pillar of Souls which sink into the girl’s flesh via hooks, flaying the girl and absorbing her into the statue. Monroe is visibly disturbed by this. ‘Jesus Christ!’, Monroe declares. ‘Not quite’, Pinhead offers dryly before commenting on his and Monroe’s ‘use’ and exploitation of the girl: ‘What did you seek? The same as I’, Pinhead suggests, ‘Appetite sated, desire indulged, a miniature of the world and how it will succumb to you. You enjoyed the girl?’ ‘Yes’, Monroe declares. ‘So did I’, Pinhead says, ‘and that’s all’. Monroe protests against this: ‘No, it’s not the same. What you did was fucking evil, man’. In response to this, Pinhead laughs heartily, telling Monroe, ‘Oh, how uncomfortable that word must feel on your lips. Evil, good. There is no good, Monroe; there is no evil. There is only flesh and the patterns to which we submit it’.

Pinhead seduces Monroe into doing his bidding by telling him, ‘Imagine a world with the body as canvas, the body as clay; your will and mine as the brush and the knife’. Pinhead promises Monroe that he will help Monroe ‘indulge’ his tastes: ‘flesh, power, dominion’. In return, Monroe must provide Pinhead with fresh victims. Later, when Terri visits Monroe’s apartment, Pinhead attempts to seduce her into doing his bidding by offering a different promise: the promise of escape. Pinhead tells Terri that by providing him with a blood sacrifice and enabling his freedom, Terri will be able to choose between ‘that world you’ve always known – banal, hopeless, dreamless’ and a world of ‘dreams, black miracles, dark wonders; another life of unknown pleasures’. Pinhead seduces Monroe into doing his bidding by telling him, ‘Imagine a world with the body as canvas, the body as clay; your will and mine as the brush and the knife’. Pinhead promises Monroe that he will help Monroe ‘indulge’ his tastes: ‘flesh, power, dominion’. In return, Monroe must provide Pinhead with fresh victims. Later, when Terri visits Monroe’s apartment, Pinhead attempts to seduce her into doing his bidding by offering a different promise: the promise of escape. Pinhead tells Terri that by providing him with a blood sacrifice and enabling his freedom, Terri will be able to choose between ‘that world you’ve always known – banal, hopeless, dreamless’ and a world of ‘dreams, black miracles, dark wonders; another life of unknown pleasures’.

The Boiler Room nightclub, with its freeflowing alcohol, music and topless dancers, seems to offer a space of hedonism which eventually pales in comparison to the disarray caused by Pinhead’s escape from the Pillar of Souls. The club itself has two realms within it: the dark and dingy nightclub, and a quiet restaurant where only classical music can be heard. The latter seems to be the domain favoured by Monroe, the owner of The Boiler Room. It’s in this space that Joey speaks with Monroe for the first time, and he reveals himself to be little more than a spoiled rich kid. When Joey visits The Boiler Room later in the game, apparently called there by her cameraman Doc (Ken Carpenter), she finds the nightclub in disarray – tortured bodies scattered throughout its hallways and suspended from the ceiling via hooks and chains. Blood flows under closed double doors, hinting at the carnage within. New Cenobites have been made: Monroe has become the ‘pistonhead’ Cenobite; ‘Doc’ has become the ‘cameraman’ Cenobite, with his video camera embedded within his skull; Terri has become the ‘dreamer’ Cenobite, with a hole torn in her throat through which she smokes her cigarettes; and the club’s DJ has become the ‘CD’ Cenobite, who shoots compact discs out of wounds in his face and body. Joey is pursued through the darkened rooms and corridors of the club by the Cenobites and their acolytes, in a sequence which seems deliberately to recall the depiction of the roving packs of possessed within the Berlin cinema in Lamberto Bava’s Demons (1985).

From here, Pinhead and his new band of Cenobites spill out onto the city streets, leaving scenes of devastation in their wake. The climactic scenes of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth take place in the city streets, which are filled with apocalyptic imagery: crashed cars, fire, explosions. With this moment, the series has transitioned from the small-scale, intimate horror of Barker’s original film to a more expansive, apocalyptic vision of Hell on Earth (as the title of this second sequel suggests). The new Cenobites come complete with catchphrases (‘That’s a wrap’, Doc/the cameraman Cenobite asserts after killing a number of police officers), and in retrospect it’s easy to see why Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth alienated some of the fans of the first two films. From here, Pinhead and his new band of Cenobites spill out onto the city streets, leaving scenes of devastation in their wake. The climactic scenes of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth take place in the city streets, which are filled with apocalyptic imagery: crashed cars, fire, explosions. With this moment, the series has transitioned from the small-scale, intimate horror of Barker’s original film to a more expansive, apocalyptic vision of Hell on Earth (as the title of this second sequel suggests). The new Cenobites come complete with catchphrases (‘That’s a wrap’, Doc/the cameraman Cenobite asserts after killing a number of police officers), and in retrospect it’s easy to see why Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth alienated some of the fans of the first two films.

In Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, the Vietnam War is conflated with World War One, and Joey’s father becomes conflated with Captain Spencer. Early in the film, after her first visit to The Boiler Room, where Monroe is storing the Pillar of Souls containing the trapped Pinhead, Joey experiences her first vision of her father, who was killed during the war in Vietnam. She sees American soldiers being ambushed by North Vietnamese troops, and witnesses her wounded father left behind by a helicopter. (‘Where are you going?’, Joey asks, ‘My daddy’s still alive!’) Joey witnesses this scene from within: in her white nightdress, Joey is a part of the scene – an omniscient observer unable to interact with her surroundings. The vision recurs throughout the film, and its via this recollection that Spencer makes his first contact with Joey: after dreaming about her father in Vietnam, Joey experiences a vision of the trenches of the First World War and is introduced to Captain Elliott Spencer for the first time. ‘I just walked into madness for you’, Joey tells Spencer after crossing into her vision of the First World War, ‘What the hell is going on?’ ‘Hell is exactly what’s going on, Joey’, Spencer tells her as they walk through the trenches in the aftermath of what appears to be a devastating battle, ‘A dream of one war is a dream of all wars. Your dream of finding your father let me find you and lead you to this place, this limbo between Heaven and Hell. I can’t act in your world, Joey, but you can’.

Captain Spencer tells Joey about the ennui that followed the First World War, saying that ‘The war pulled poetry out of some of us. Others it affected differently [….] I was like many survivors: a lost soul with nothing left in which to believe but gratification. We’d seen God fail, you see. So many dead. For us, He too fell at Flanders’. The Great War destroyed Spencer’s generation: ‘those that didn’t die drank themselves to death’, he tells Joey, ‘I was an explorer of forbidden pleasures; opening the box my act of exploration, of discovery. I found the monster within the box; I found the monster within me’. The confusion of the two conflicts (‘a dream of one war is a dream of all wars’) seems to pinpoint a similar sense of ennui within America following the Vietnam War, and Christoper Sharrett suggests that the film thus offers ‘another attempt, a la The Exorcist (1973), to make the devil carry the bag for a variety of political-economic phenomena’ (Sharrett, op cit.: 291). Captain Spencer tells Joey about the ennui that followed the First World War, saying that ‘The war pulled poetry out of some of us. Others it affected differently [….] I was like many survivors: a lost soul with nothing left in which to believe but gratification. We’d seen God fail, you see. So many dead. For us, He too fell at Flanders’. The Great War destroyed Spencer’s generation: ‘those that didn’t die drank themselves to death’, he tells Joey, ‘I was an explorer of forbidden pleasures; opening the box my act of exploration, of discovery. I found the monster within the box; I found the monster within me’. The confusion of the two conflicts (‘a dream of one war is a dream of all wars’) seems to pinpoint a similar sense of ennui within America following the Vietnam War, and Christoper Sharrett suggests that the film thus offers ‘another attempt, a la The Exorcist (1973), to make the devil carry the bag for a variety of political-economic phenomena’ (Sharrett, op cit.: 291).

In an interview with Paul Wells, Barker has reflected on the Gothic influences in his work, suggesting that ‘I don’t think you can ever avoid the long shadow of the Gothic, but I think one of the distressing elements of the influence of the Gothic is that it brings with it a whole theological machinery which in my view is redundant’ (Barker, quoted in Wells, op cit.: 175). Barker questions ‘how many people actually watching’ Hammer’s Dracula (Terence Fisher, 1957) ‘believed in the power of the crucifix’, and he suggests that ‘[t]he modern audience can only take that kind of narrative machinery if the tongue is reasonably firmly in the cheek’ (Barker, quoted in ibid.). In Hellraiser, Frank’s home is decorated with bizarre, garish and commercial religious ephemera – pointing ironically to the commercialisation of faith – which sit alongside Frank’s erotic statues and homemade pornographic Polaroids. When Larry and Julia move into the house, it is a Sunday, and in the background church bells can be heard ringing. When, in Julia’s memory, Frank introduces himself, he declares himself to be ‘Frank. I’m brother Frank’. Frank is of course referring to his status as the brother of Larry, to whom Julia is to be wed, but the title ‘Brother Frank’ also suggests someone who belongs to a religious order: prior, of course, to his encounter with the Lament Configuration, Frank has considered it his vocation not to practise ascetism but instead to devote his life to hedonistic pleasure.

The opening sequence of Hellbound: Hellraiser II depicts Elliott Spencer’s transformation into Pinhead following his solving of the Lament Configuration. As the puzzle box opens and Spencer’s suffering begins, we hear him cry out, ‘Oh, my God. Jesus!’. Soon, however, he sings a different tune, intoning, ‘Ah, the suffering. The sweet suffering’. Elsewhere in the film, God’s name is invoked in desperation. When Channard enters the labyrinth and sees Leviathan for the first time, Channard declares ‘Oh, my God’. ‘No, this is my god’, Julia tells him, ‘not yours. The god that sent me back. The god I serve in this world and yours. The god of flesh, hunger and desire. My god, Leviathan: lord of the labyrinth’. Likewise, in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, when J P Monroe sees his one night stand attacked by Pinhead and drawn into the Pillar of Souls, he cries out, ‘Jesus Christ!’ Pinhead’s response is to state, quite simply, ‘Not quite’. The allusions to the Christian faith are brought front-and-centre in a sequence in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth when, after the carnage within The Boiler Room has spilled out onto the city streets, Joey seeks refuge in a Catholic church. She approaches the priest and tells him that demons are coming. ‘Demons aren’t real’, the priest reassures her, ‘They’re parables, metaphors’. It is at this point that Pinhead enters the church, and pointing to Pinhead Joey asks the priest, ‘Then what the fuck is that?’ Pinhead approaches the altar and sweeps aside the items which stand upon it before adopting the cruciform pose in a mockery of the crucifixion. ‘I am the way’, Pinhead intones. Pinhead then forces the priest to eat of Pinhead’s flesh in a perversion of the Communion rite. ‘You’ll burn in Hell for this’, the priest tells Pinhead. ‘Burn?’, Pinhead scoffs in response, ‘Of such limited imagination!’ The opening sequence of Hellbound: Hellraiser II depicts Elliott Spencer’s transformation into Pinhead following his solving of the Lament Configuration. As the puzzle box opens and Spencer’s suffering begins, we hear him cry out, ‘Oh, my God. Jesus!’. Soon, however, he sings a different tune, intoning, ‘Ah, the suffering. The sweet suffering’. Elsewhere in the film, God’s name is invoked in desperation. When Channard enters the labyrinth and sees Leviathan for the first time, Channard declares ‘Oh, my God’. ‘No, this is my god’, Julia tells him, ‘not yours. The god that sent me back. The god I serve in this world and yours. The god of flesh, hunger and desire. My god, Leviathan: lord of the labyrinth’. Likewise, in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, when J P Monroe sees his one night stand attacked by Pinhead and drawn into the Pillar of Souls, he cries out, ‘Jesus Christ!’ Pinhead’s response is to state, quite simply, ‘Not quite’. The allusions to the Christian faith are brought front-and-centre in a sequence in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth when, after the carnage within The Boiler Room has spilled out onto the city streets, Joey seeks refuge in a Catholic church. She approaches the priest and tells him that demons are coming. ‘Demons aren’t real’, the priest reassures her, ‘They’re parables, metaphors’. It is at this point that Pinhead enters the church, and pointing to Pinhead Joey asks the priest, ‘Then what the fuck is that?’ Pinhead approaches the altar and sweeps aside the items which stand upon it before adopting the cruciform pose in a mockery of the crucifixion. ‘I am the way’, Pinhead intones. Pinhead then forces the priest to eat of Pinhead’s flesh in a perversion of the Communion rite. ‘You’ll burn in Hell for this’, the priest tells Pinhead. ‘Burn?’, Pinhead scoffs in response, ‘Of such limited imagination!’

The film’s final scenes contain what perhaps are some of its strongest ideas. After the threat represented by Pinhead and his Cenobites has been quashed, Joey wanders through the devastated city landscape and buries the Lament Configuration in some wet cement on a building site. Via a montage, we are shown a new building being constructed around the site where the puzzle box is buried – and outside this new building is a strange, esoteric statue, whilst inside the architectural style of the building has taken on the aesthetic of the puzzle box itself. There’s a hint here of an exploration of the relationships between occultism and architecture – of the kind highlighted in the myths surrounding the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor – but, like many of the ideas within the film it’s unformed and frustratingly underdeveloped.

All three films fell foul of the censors, in one way or another. Hellraiser was cut by the MPAA for an ‘R’ rating in 1987. The MPAA stipulated the removal of some of Julia’s attacks on her victims with the hammer, Frank’s penetration of his victims’ skulls with his fingers, the sex scene between Frank and Julia, and trims to the death of Frank/Larry. It was this ‘R’ rated version which suffered further cuts by the BBFC when submitted for home video classification. The ‘R’ rated version of Hellraiser has become the definitive cut of the film, and it is this cut of the picture that is presented – with the BBFC’s previous cuts waived – on this Blu-ray release. The running time is 93:20 mins. All three films fell foul of the censors, in one way or another. Hellraiser was cut by the MPAA for an ‘R’ rating in 1987. The MPAA stipulated the removal of some of Julia’s attacks on her victims with the hammer, Frank’s penetration of his victims’ skulls with his fingers, the sex scene between Frank and Julia, and trims to the death of Frank/Larry. It was this ‘R’ rated version which suffered further cuts by the BBFC when submitted for home video classification. The ‘R’ rated version of Hellraiser has become the definitive cut of the film, and it is this cut of the picture that is presented – with the BBFC’s previous cuts waived – on this Blu-ray release. The running time is 93:20 mins.

Hellbound: Hellraiser II was again cut for an ‘R’ rating in America; this ‘R’ rated version was shown without cuts in UK cinemas but was trimmed by the BBFC for the UK home video release. The unrated US version, which contains an extra six minutes of footage in comparison with the original ‘R’ rated edit (adding footage to most of the film’s moments of violence), has since been passed uncut by the BBFC, and it’s this uncut, unrated version of the film that’s included on Arrow’s new BD. The running time is 99:00 mins.

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth was again cut for an ‘R’ rating in America, with no cuts imposed by the BBFC for the film’s UK release. In fact, the UK VHS release contained the unrated version of the film, which included some additional moments of violence but mostly reinstated brief expository scenes. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release presents the viewer with the option of watching the ‘R’ rated cut (running 93:07 mins) or the unrated version (running 96:38 mins). The unrated cut is a composite of sorts, featuring some of the material exclusive to the unrated cut spliced in from a lesser-quality source (a LaserDisc release of the unrated version). These scenes include: (i) Joey at the door of The Boiler Room; (ii) more scenes inside the nightclub, including a girl stripping, Joey talking, and people dancing; (iii) The club’s employees leaving at the end of their shift; (iv) Terri in the a bar, staring into a cup of coffee as she waits for Monroe to arrive; (v) more shots of dead bodes in the First World War trenches; (vi) Spencer leading Joey through the bazaars of India.

Video

Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II both take up approximately 30Gb on their respective discs; Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth is about 18Gb in size. All three films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio – though the inserts included in the unrated cut of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth are from a cropped 4:3 source. All three presentations are based on new 2k restorations, with the presentations of the first three films being based on restorations approved by cinematographer Robin Vidgeon. Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II both take up approximately 30Gb on their respective discs; Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth is about 18Gb in size. All three films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio – though the inserts included in the unrated cut of Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth are from a cropped 4:3 source. All three presentations are based on new 2k restorations, with the presentations of the first three films being based on restorations approved by cinematographer Robin Vidgeon.

Hellraiser was shot mostly in an Edwardian house with narrow hallways and a narrow staircase. The film was shot predominantly in close-ups and wide shots, with dollies used to follow the characters around the house – in a deliberate attempt to avoid ‘static’ medium shots, etc (see Vidgeon, interviewed in Ellis, 2012: 91). The night-time sequences were shot in daylight, with the windows of the house blacked out, and lights carefully placed where they couldn’t be seen by the camera (Vidgeon, interviewed in ibid.). The stock used on the film seems to be a fast stock, or one that has been ‘pushed’: the film has always had a coarse appearance, with a very pronounced grain structure that previous digital video releases have struggled to resolve. Arrow’s Blu-ray release offers a distinct improvement on the film’s previous UK Blu-ray release from Starz (some screen grabs comparing the two releases are below). Arrow’s release contains an image that is rich in detail and displays well-balanced contrast levels – particularly beneficial to a film which features so much low-light photography, with the shadows being deep and dark, as they should be. Some sequences feature heavily diffused light or characters framed by a light source, which can result in a slightly ‘soft’ appearance to some shots. This diffuse light (for example, during the final stages of Frank’s resurrection) is a characteristic of the original photography, and is captured well on this Blu-ray release. The encode is superb, resolving the detail and robust, organic grain of the film in a manner that ensures the presentation has the appearance of 35mm film – or as close to that experience as a digital simulacrum will allow.