|

|

The Film

Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe/Tenderness of the Wolves/The Tenderness of Wolves (Ulli Lommel, 1973) Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe/Tenderness of the Wolves/The Tenderness of Wolves (Ulli Lommel, 1973)

Produced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and originally intended as a project for Fassbinder to direct (Fassbinder reputedly baulked at the project because he felt it too contentious, though he acts in a small role within the finished film), Tenderness of the Wolves was directed by Ulli Lommel. Lommel appeared as an actor in a significant number of Fassbinder’s films, beginning with Fassbinder’s directorial debut Lieber ist kälter als der Tod/Love is Colder Than Death (1969). For a time, Lommel was also associated with Andy Warhol, who produced some of Lommel’s pictures in the late 1970s. In 1977, Lommel moved to America, where he made films that have often – sometimes unfairly – been critically derided, such as The Bogey Man/The Boogeyman (1980). (Lommel is apparently currently working on another sequel to The Boogey Man, Boogey Man: Reincarnation.) Also heavily criticised have been Lommel’s recent run of ‘true crime’ films about American serial killers: 2005’s Zodiac Killer, BTK Killer and Green River Killer; 2006’s Black Dahlia and Killer Pickton; Curse of the Zodiac, 2007; 2008’s Son of Sam and Baseline Killer; Night Stalker, 2009; and Manson Family Cult, 2012. Having its roots in the story of real life serial killer Fritz Haarman, whose horrendous crimes in Hanover during the early 1920s also partially inspired Fritz Lang’s M (1931), Tenderness of the Wolves has some obvious similarities with Lommel’s later serial killer-focused pictures. (A later film – Romauld Karmaker’s Der Totmacher/Deathmaker, 1995 – focused on the interrogation of Haarmann by a psychiatrist prior to Haartmann’s execution at the guillotine in 1925.) In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, during the American occupation of Germany, Inspector Müller (Rainer Hauer) of the Hanover police discusses with an American major from the occupying force the discovery of human remains near the canal. The German police are apparently dismissing the discovery of these corpses as simply being the product of grave robberies or thefts from the Gottingen Institute of Anatomy.  Following this, Fritz Haarmann (Kurt Raab) is interrupted in a post-coital embrace by the police, who take him to the police station where he is interrogated by Inspector Braun (Wolfgang Schenck). Braun and Haarmann reach an agreement: Haarmann, a conman and black marketeer, will be allowed to continue his activities unmolested by the police if he promises to become an informant, passing information to the police about the criminal activities of some of his associates. Following this, Fritz Haarmann (Kurt Raab) is interrupted in a post-coital embrace by the police, who take him to the police station where he is interrogated by Inspector Braun (Wolfgang Schenck). Braun and Haarmann reach an agreement: Haarmann, a conman and black marketeer, will be allowed to continue his activities unmolested by the police if he promises to become an informant, passing information to the police about the criminal activities of some of his associates.

Haarmann and his lover, Hans Grans (Jeff Roden, dubbed by Lommel himself), spend their days pretending to be charity workers, collecting ‘donations’ from more wealthy areas of the city which they then exchange or sell on the black market. (A number of times, Haarmann and Grans are shown exchanging the clothes they have acquired with a soldier from the French Foreign Legion, played by El Hedi ben Salem.) Haarmann also has a friendly relationship with Dora (Ingrid Craven), who sometimes helps Haarmann to clean his rooms. Pretending to be a detective, Haarmann cruises the railway stations for young men who he then takes back to his rooms. Haarmann murders these young men by strangling them and biting their Adam’s apples, disposing of their bodies in the rivers and canals. Meanwhile, Grans falls under the spell of another black marketeer, Wittowski (played by Fassbinder) and seems to turn against Haarmann. In the midst of this, the mother of a young boy that Haarmann has killed approaches the police and asks for help in finding her son. The real Fritz Haarmann committed his crimes in the years following the First World War. Lommel’s version of this story (vaguely) relocates these events to the years following the Second World War, during the US occupation of Germany: in the interview on this disc, Lommel says that the setting ‘didn’t make any difference to me anyway, plus I thought that the Americans looked sexier, the soldiers, after World War 2 than after World War 1’. (The temporal setting of the film is quite ambiguous, however: Rainer Will says in his interview on this Blu-ray release that the film takes place in the 1920s; it’s this indefinite, liminal quality – aware of history but separate from it – within the film that connects it with the pictures Fassbinder directed.) The depiction of post-war Germany is chilly and bleak. The society within Tenderness of the Wolves is one that is riddled with poverty and held back by bureaucracy. Haarmann, it seems, is able to extend his spree of murder and butchery by: (i) the complacency of the majority of his neighbours and associates, and their own vested interests in staying off the radar of the police force owing to their involvement in the black market and prostitution; (ii) the ethically questionable but mutually beneficial deal that exists between the local police and Haarmann (that he is an informant and therefore is allowed special dispensation to carry on his black market activities); and (iii) the bureaucracy that exists between the local police force and the US military occupiers. Haarmann’s crimes seem simply a heightened representation of the ‘cannibalistic’ relationships that exist between people within this society. There’s also a subtle reference to the Nazi era, when the American major presses the police to ‘present results’ owing to the perception by ‘various parts of the military government […] that the German police are working hand in hand with shady elements from the Nazi period’.  The film is democratic in its scorn for the members of this society. Haarmann’s associates – pimps, hookers and con-men – are ridiculed within the picture, as are the American occupiers and the police who become involved in the investigation. As the murders reveal themselves, the Americans and the police regard the crimes with detachment and a lack of concern. In the opening scene, Inspector Muller discusses with the American major the discovery of another skull in the area near the canal. ‘Eighteen to twenty years of age’, Muller states, ‘Severed from the body with a sharp scalpel’. The skulls, he claims, are wrongly identified by the German police as having been stolen from Gottingen’s Institute of Anatomy and ‘from grave desecrations’: there is a refusal amongst the authorities to believe that they are from recent murders. After listening to Muller, the American major offers a dismissive approach to the victims of Haarmann’s crimes, stating ‘What difference do a few bodies make?’ Later, when the mother of the young boy – who is only five or six – that Haarmann kills in the film’s most unsettling sequence approaches the police and asks them to find her son, her plea for help is dismissed with the suggestion that the boy has simply run away from home and will return in due course. The film is democratic in its scorn for the members of this society. Haarmann’s associates – pimps, hookers and con-men – are ridiculed within the picture, as are the American occupiers and the police who become involved in the investigation. As the murders reveal themselves, the Americans and the police regard the crimes with detachment and a lack of concern. In the opening scene, Inspector Muller discusses with the American major the discovery of another skull in the area near the canal. ‘Eighteen to twenty years of age’, Muller states, ‘Severed from the body with a sharp scalpel’. The skulls, he claims, are wrongly identified by the German police as having been stolen from Gottingen’s Institute of Anatomy and ‘from grave desecrations’: there is a refusal amongst the authorities to believe that they are from recent murders. After listening to Muller, the American major offers a dismissive approach to the victims of Haarmann’s crimes, stating ‘What difference do a few bodies make?’ Later, when the mother of the young boy – who is only five or six – that Haarmann kills in the film’s most unsettling sequence approaches the police and asks them to find her son, her plea for help is dismissed with the suggestion that the boy has simply run away from home and will return in due course.

The police’s apparent unwillingness to act on the evidence as to the existence of a serial killer within the city, which presents itself very readily to them, is compounded by an agreement that is reached between Haarmann and Inspector Braun: Braun asks Haarmann to work as an informant for the police in exchange for a promise that Haarmann will be allowed to continue his black market activities. ‘You are useless to us in jail. Remember that’, Braun tells Haarmann. In a later sequence, Braun reminds Haarmann that ‘You’re a reliable and valuable aide’. This agreement provides Haarmann with a method by which he is able to procure his potential victims, preying on their vulnerability and presenting himself to them as a detective before offering them help with the police, or with their hunger and lack of shelter.  Frau Linder, the sole neighbour of Haarmann’s who seems to realise that Haarmann is up to no good, is equally unsympathetic. Several times, whilst Haarmann is, we presume, killing his victims or cleaning up after his crimes, Linder is shown in her rooms listening to the sounds within Haarmann’s bedsit with a clear sense of fear upon her face. However, she’s slow to take action and report Haarmann to the police, and in her interactions with Haarmann himself she comes across as little more than a harridan. When Frau Linder finally tells the police of her suspicions regarding Haarmann (‘He pounds and chops for hours’, she says), her claims are dismissed by the police, who accuse her of ‘jumping to conclusions’. Meanwhile, the other neighbours ridicule Linder, insisting to her that Haarmann is ‘a good man’. For her part, Dora too becomes aware of Haarmann’s crimes, though she seems to choose to deliberately ignore them. Dora pays a visit to Haarmann immediately after he has killed a young man, and sees the corpse on Haarmann’s bed. Haarmann covers the body with a blanket, and tells Dora that the boy is simply very tired. Although it is clearly a corpse that she has seen, Dora seems to accept Haarmann’s story unquestioningly, until shortly after Haarmann has disposed of the young man’s corpse she spots the boy’s clothes in Haarmann’s rooms. Cognisant of the death of the boy, Dora nevertheless does nothing. Frau Linder, the sole neighbour of Haarmann’s who seems to realise that Haarmann is up to no good, is equally unsympathetic. Several times, whilst Haarmann is, we presume, killing his victims or cleaning up after his crimes, Linder is shown in her rooms listening to the sounds within Haarmann’s bedsit with a clear sense of fear upon her face. However, she’s slow to take action and report Haarmann to the police, and in her interactions with Haarmann himself she comes across as little more than a harridan. When Frau Linder finally tells the police of her suspicions regarding Haarmann (‘He pounds and chops for hours’, she says), her claims are dismissed by the police, who accuse her of ‘jumping to conclusions’. Meanwhile, the other neighbours ridicule Linder, insisting to her that Haarmann is ‘a good man’. For her part, Dora too becomes aware of Haarmann’s crimes, though she seems to choose to deliberately ignore them. Dora pays a visit to Haarmann immediately after he has killed a young man, and sees the corpse on Haarmann’s bed. Haarmann covers the body with a blanket, and tells Dora that the boy is simply very tired. Although it is clearly a corpse that she has seen, Dora seems to accept Haarmann’s story unquestioningly, until shortly after Haarmann has disposed of the young man’s corpse she spots the boy’s clothes in Haarmann’s rooms. Cognisant of the death of the boy, Dora nevertheless does nothing.

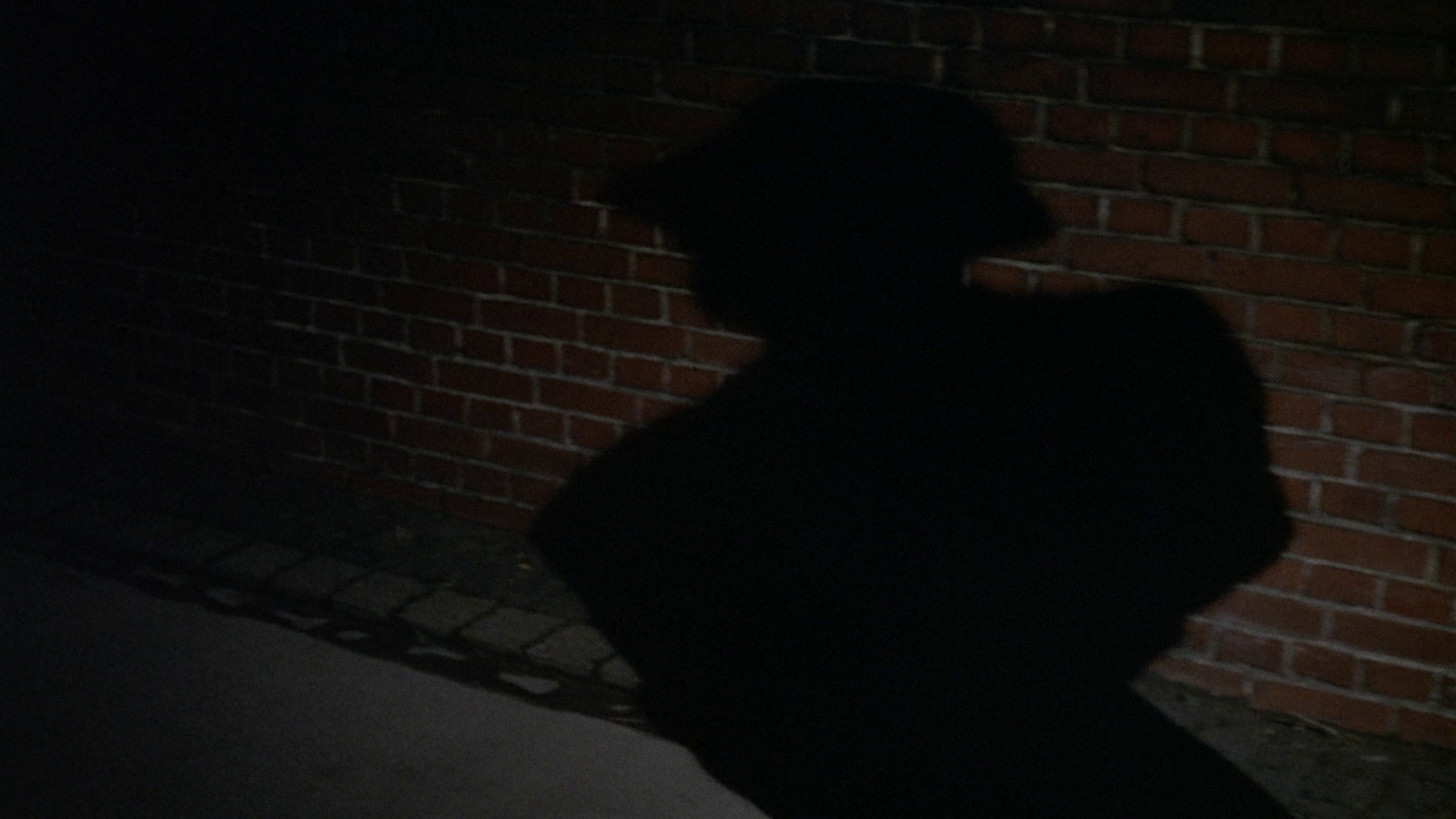

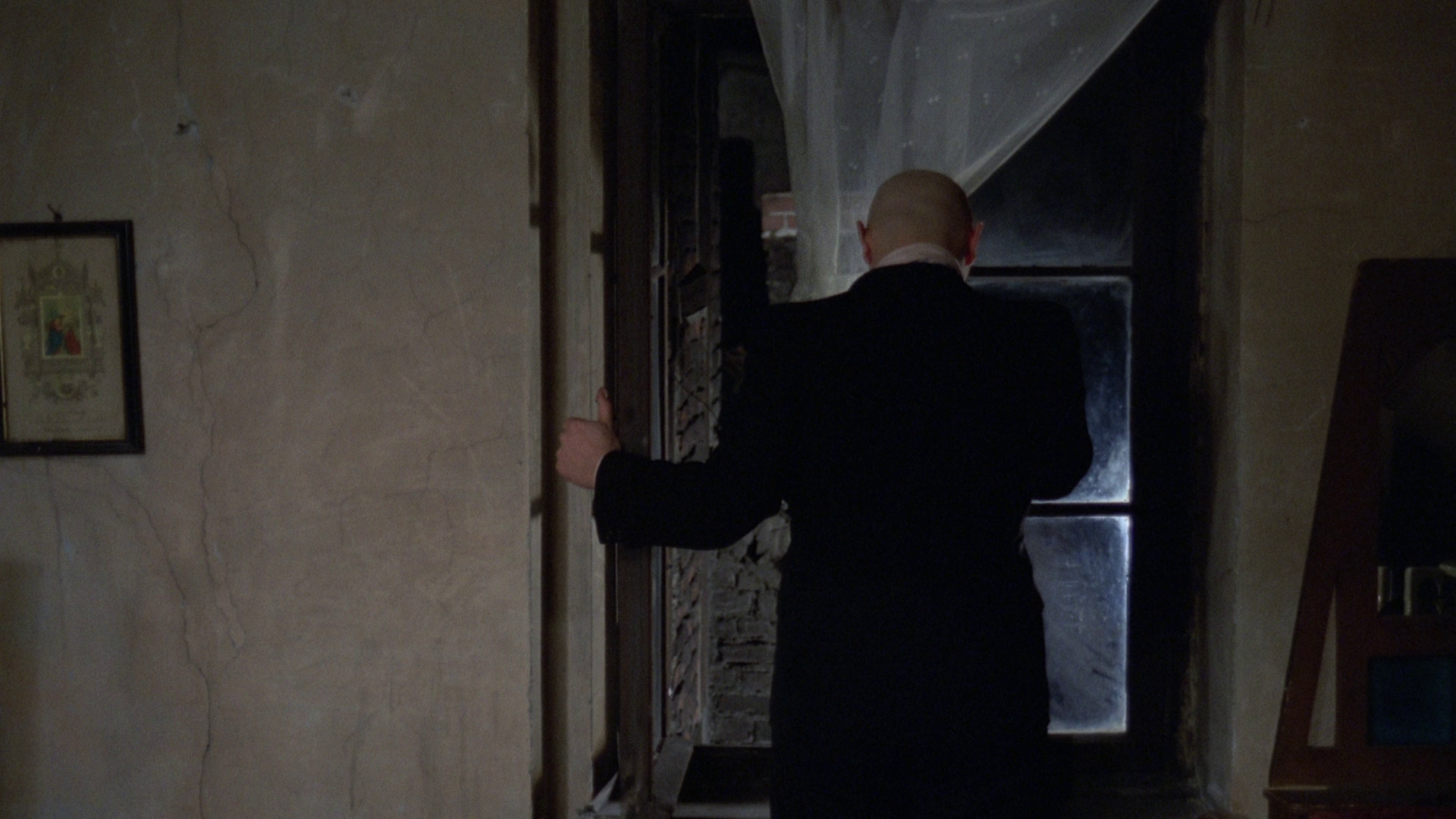

The blasé attitude of Haarmann’s neighbours and friends to his crimes is established in the opening sequence. In this sequence, one of Haarmann’s female neighbours listens to the sounds in Haarmann’s rooms; these noises sound ominous even in this context but later in the film become more directly associated with Haarmann’s post-murder rituals. The woman knocks on the adjoining wall and asks Haarmann, ‘Will I get some tomorrow? [….] Some of your meat?’ Following this, we are presented with the film’s opening titles, which feature Haarmann’s slow, steady footsteps and his shadow which falls across a wall as he walks along a street. The camera smoothly tracks on a dolly with Haarmann’s shadow until, finally, the camera comes to a halt and Haarmann’s shadow continues to walk away from us.  Haarmann seems to take his agreement with Inspector Braun as an implicit acceptance of Haarmann’s activities, and Haarmann even pretends to be a detective whilst cruising for victims at the city’s train stations, where he selects young men who appear to be runaways or transients. Haarmann is shown picking up the first of these victims at the railway station; Haarmann masquerades as a police officer, telling the young man to ‘Come with me’. Haarmann brings the young man back to his lodgings, where Haarmann offers his victim hospitality. In the background, a large cross is shown hanging on the wall; this is a feature of the mise-en-scène that the photography will draw the viewer’s eye towards repeatedly throughout the film, often composing shots with Haarmann on one side of the cross and other characters on the opposite side, the cross effectively bisecting the frame. With his first victim, Haarmann demonstrates his exploitation of the vulnerability of the young men on whom he preys. ‘I accommodate young people like you here that have run away from home’, Haarmann tells the boy he picks up at the railway station, ‘I was supposed to bring you to the police station. They would have locked you up’. Haarmann then slowly begins to strip the young man whilst continuing to speak, ‘But I don’t want that for people like you. There is a better place for you’. With this, Haarmann removes the young man’s trousers and pulls him down onto the bed. An ironic cut take place, to a low-angle shot looking up the staircase towards Haarmann’s lodgings, the next morning. Haarmann descends the stairs; he is carrying a bowl of meat, which he takes to the restaurant across the road. Haarmann seems to take his agreement with Inspector Braun as an implicit acceptance of Haarmann’s activities, and Haarmann even pretends to be a detective whilst cruising for victims at the city’s train stations, where he selects young men who appear to be runaways or transients. Haarmann is shown picking up the first of these victims at the railway station; Haarmann masquerades as a police officer, telling the young man to ‘Come with me’. Haarmann brings the young man back to his lodgings, where Haarmann offers his victim hospitality. In the background, a large cross is shown hanging on the wall; this is a feature of the mise-en-scène that the photography will draw the viewer’s eye towards repeatedly throughout the film, often composing shots with Haarmann on one side of the cross and other characters on the opposite side, the cross effectively bisecting the frame. With his first victim, Haarmann demonstrates his exploitation of the vulnerability of the young men on whom he preys. ‘I accommodate young people like you here that have run away from home’, Haarmann tells the boy he picks up at the railway station, ‘I was supposed to bring you to the police station. They would have locked you up’. Haarmann then slowly begins to strip the young man whilst continuing to speak, ‘But I don’t want that for people like you. There is a better place for you’. With this, Haarmann removes the young man’s trousers and pulls him down onto the bed. An ironic cut take place, to a low-angle shot looking up the staircase towards Haarmann’s lodgings, the next morning. Haarmann descends the stairs; he is carrying a bowl of meat, which he takes to the restaurant across the road.

The real Fritz Haarmann was known to have sold black market meat, and after Haarmann was arrested there was a suggestion that the meat he sold was in fact stripped from the corpses of his victims – though this has never been officially confirmed. Tenderness of the Wolves demonstrates considerable ambiguity towards this issue. After what we presume is the murder of his first victim within the film’s narrative (though this murder isn’t shown on screen), Haarmann is shown taking contraband meat, a luxury item, to his friends at the restaurant; the suggestion is that this may be meat stripped from the corpse of the young man Haarmann picked up at the railway station. (Later in the film, Inspector Braun is shown as the exceptionally grateful recipient of some of Haarmann’s contraband meat.) Haarmann is shown enjoying this meat with his friends, who sit around a table after closing time eating a meal. It’s here that Haarmann’s lover, Hans, is introduced to the film’s audience. During the meal, Haarmann makes a show of being interested in Dora, though his peccadilloes – known to his friends – make Haarmann the subject of gentle ridicule. They joke about Haarmann’s effeminate ways, saying that he would make the perfect housewife; more directly, Dora jokes about Haarmann’s taste in young men, saying ‘But he only wants to kiss his young boys’.  Grans’ ridicule of Haarmann leads to conflict between the couple. Grans seemingly accepts Haarmann’s need to pick up young men for sex, and Grans is also apparently aware of Haarmann’s actions as a murderer. For his part, Haarmann seems to resent Grans’ tendency to, as Haarmann sees it, act as a freeloader. Early in the film, Haarmann and Grans are shown having an argument. ‘What are you without me?’, Haarmann asks Grans before reminding him, ‘A dirty little pimp, that’s what you are. You let these women keep you’. Haarmann criticises Grans for ‘mock[ing] me in front of your women’, including Dora, at the restaurant. In response, Grans departs, muttering softly, ‘Murderer!’ Grans’ ridicule of Haarmann leads to conflict between the couple. Grans seemingly accepts Haarmann’s need to pick up young men for sex, and Grans is also apparently aware of Haarmann’s actions as a murderer. For his part, Haarmann seems to resent Grans’ tendency to, as Haarmann sees it, act as a freeloader. Early in the film, Haarmann and Grans are shown having an argument. ‘What are you without me?’, Haarmann asks Grans before reminding him, ‘A dirty little pimp, that’s what you are. You let these women keep you’. Haarmann criticises Grans for ‘mock[ing] me in front of your women’, including Dora, at the restaurant. In response, Grans departs, muttering softly, ‘Murderer!’

Discussing the differences between Fritz Lang’s M and Lommel’s approach to the crimes of Fritz Haarmann, Robert C Reimer and Carol J Reimer suggest that where Lang’s film focuses ‘on the psychology behind’ the murders committed by Haarmann, Lommel’s picture ‘takes liberties with the facts and focuses on the homoerotic nature of a man who killed boys to feed them to his friends’ (Reimer & Reimer, 2009: 190). However, the Reimers’ approach to Lommel’s film is arguably reductive: there’s a strong case to be made for the argument that Tenderness of the Wolves sticks closer to the known facts of the Haarmann murders. For one thing, Lommel’s film retains the ambiguity surrounding the meat black marketeer Haarmann provided for his friends and associates (was it human or not?); it also identifies the victims of Haarmann as young men and boys, whereas the Lang film, perhaps afraid of depicting homosexuality, substituted these for young girls; and Tenderness of the Wolves retains at least one statement made by one of the people involved in the Haarmann’s case (Grans’ ominous declaration, in relation to a young man who was to become one of Haarmann’s victims, that ‘He’ll be trampled tonight’). There are some liberties taken too: by far the youngest known victim of Haarmann was ten, whereas in Lommel’s film one of Haarmann’s victims is a young boy of five or six.  It’s this sequence, Lommel’s film’s equivalent of Lang’s elliptical depiction of the murder of Elsie Beckmann in M, which is Tenderness of Wolves’ most disturbing. Haarmann is shown walking along a street when a young child leans out of a window and sings a song which suggests that knowledge of Haarmann’s crimes – at least, his role in the disappearance of young men – is widespread: ‘Uncle Fritz! Fritz, Fritz, let’s go. Fritz, Fritz, take me away. Fritz, Fritz, how much do you pay?’ The little boy enters the building in which Haarmann lives. He is looking for Haarmann. He knocks on the door of Frau Linder, who advises the boy to go home and warns him obliquely of Haarmann’s cruelty. The boy seems to descend the stairs, but when Frau Linder has returned to her rooms, the boy does an about-face and climbs up to the top of the stairs before knocking on Haarmann’s door. Lommel cuts to Frau Linder in her rooms. She is framed in menacing shadow, her hands to her face and throat as she looks upwards towards the ceiling, above which are Haarmann’s rooms. A look of dread is upon her face as she listens to Haarmann’s footsteps and the thuds which we may interpret as indices of something dreadful being done to the young child or his corpse. We share Frau Linder’s horror but may be frustrated by her lack of action. (To some extent, this recalls the sequence in Hitchcock’s The Lodger, 1927, when Hitchcock uses a glass ceiling and swinging chandelier to depict the family living below the murder suspect played by Ivor Novello listening as he paces his rooms.) In the next scene, Haarmann is shown walking along a railway line. He sees some children playing amongst the old carriages and trucks. He approaches these children and gives one of them the blue hat that we saw the little boy wearing in the earlier scene. ‘I took it from a naughty boy’, Haarmann tells the child to whom he gives the hat. It’s this sequence, Lommel’s film’s equivalent of Lang’s elliptical depiction of the murder of Elsie Beckmann in M, which is Tenderness of Wolves’ most disturbing. Haarmann is shown walking along a street when a young child leans out of a window and sings a song which suggests that knowledge of Haarmann’s crimes – at least, his role in the disappearance of young men – is widespread: ‘Uncle Fritz! Fritz, Fritz, let’s go. Fritz, Fritz, take me away. Fritz, Fritz, how much do you pay?’ The little boy enters the building in which Haarmann lives. He is looking for Haarmann. He knocks on the door of Frau Linder, who advises the boy to go home and warns him obliquely of Haarmann’s cruelty. The boy seems to descend the stairs, but when Frau Linder has returned to her rooms, the boy does an about-face and climbs up to the top of the stairs before knocking on Haarmann’s door. Lommel cuts to Frau Linder in her rooms. She is framed in menacing shadow, her hands to her face and throat as she looks upwards towards the ceiling, above which are Haarmann’s rooms. A look of dread is upon her face as she listens to Haarmann’s footsteps and the thuds which we may interpret as indices of something dreadful being done to the young child or his corpse. We share Frau Linder’s horror but may be frustrated by her lack of action. (To some extent, this recalls the sequence in Hitchcock’s The Lodger, 1927, when Hitchcock uses a glass ceiling and swinging chandelier to depict the family living below the murder suspect played by Ivor Novello listening as he paces his rooms.) In the next scene, Haarmann is shown walking along a railway line. He sees some children playing amongst the old carriages and trucks. He approaches these children and gives one of them the blue hat that we saw the little boy wearing in the earlier scene. ‘I took it from a naughty boy’, Haarmann tells the child to whom he gives the hat.

Peter Hutchings suggests that Lommel’s film evidences Fassbinder’s ‘influence in its emphasis on destructive gay sexuality and its awareness of German history’ (Hutchings, 2009: 203). Certainly, for much of its running time, Tenderness of the Wolves has the cold, objective and elliptical approach of a docudrama – its approach to Haarmann’s life and crimes having much in common with American semi-documentary films noir, such as Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948), of the post-war period – but occasionally the film explodes into a world of nightmares, as if haunted by the extremes of German Expressionist horror pictures such as F W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922). In this sense, the film has some strong similarities with Cesare Ferrario’s 1986 film about the then-current crimes of the ‘Monster of Florence’, Il mostro di Firenze (The Monster of Florence) and David Fincher’s later Zodiac (2005), both of which are films based on true crimes which offer a predominantly semi-documentary approach within a framework which also includes diversions into the paradigms of the horror film. Raab, who also wrote the film, is striking in his role as Haarmann. His performance is for much of the film fairly naturalistic and low-key, but during a handful of sequences the predatory aspects of the character are pushed to the foreground, reminding us of the various horror-themed nicknames that have been associated with Haarmann owing to the nature of his crimes (Haarmann has been referred to variously as the ‘Wolf Man’, the ‘Vampire of Hanover’ and the ‘Butcher of Hanover’). As Haarman, Raab has a shaved head, which makes his boyish face even more childlike; this was something which Raab, according to the interview with Lommel on this disc, initially resisted but which became an integral part of the character. In one scene, at the restaurant, Haarmann sees a young boy with blonde hair. He advances towards the child like a predator; his slow approach to the boy is reminiscent of the horror film monsters of the era of German Expressionism (Max Schreck’s Nosferatu, for example, or Conrad Veidt’s performance as the somnambulist Cesare in Robert Wiene’s Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari/The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, 1920). Haarmann only snaps out of his trance, reverting back to his usual affable self, when he hears his name (‘Fritz!’) called out.  Haarmann’s crimes slowly unravel as the film progresses. The audience is aware that Haarmann is killing the young men whom he invites into his lodgings, but we don’t actually see Haarmann committing the act of murder until a good way into the film. He returns one of the young men to his rooms and strips him before strangling him with his bare hands and kissing him on the neck. The kiss leads to Haarmann biting the young man’s throat (the real Haarmann referred to these ‘kisses’, in which he bit through the Adam’s apples of his victims, as his ‘love bites’); this is an act which carries obvious symbolism and associates Haarmann with the myth of the vampire. Only one other comparable scene of violence is included within the film: at the climax, Haarmann invites another young man into his rooms and begins to attack him when the police arrive, thus saving Haarmann’s intended victim. In the interview with Lommel that is included on this disc, Lommel argues that by delaying the first scene in which Haarmann is shown committing murder until later in the narrative, he placed the audience in a position of sympathy with Haarmann before revealing him to be a ‘monster’; Lommel suggests that this was confirmed for him by the reactions of the audiences during the first screenings of the picture. Haarmann’s crimes slowly unravel as the film progresses. The audience is aware that Haarmann is killing the young men whom he invites into his lodgings, but we don’t actually see Haarmann committing the act of murder until a good way into the film. He returns one of the young men to his rooms and strips him before strangling him with his bare hands and kissing him on the neck. The kiss leads to Haarmann biting the young man’s throat (the real Haarmann referred to these ‘kisses’, in which he bit through the Adam’s apples of his victims, as his ‘love bites’); this is an act which carries obvious symbolism and associates Haarmann with the myth of the vampire. Only one other comparable scene of violence is included within the film: at the climax, Haarmann invites another young man into his rooms and begins to attack him when the police arrive, thus saving Haarmann’s intended victim. In the interview with Lommel that is included on this disc, Lommel argues that by delaying the first scene in which Haarmann is shown committing murder until later in the narrative, he placed the audience in a position of sympathy with Haarmann before revealing him to be a ‘monster’; Lommel suggests that this was confirmed for him by the reactions of the audiences during the first screenings of the picture.

The film has variously been known amongst English-speaking cinephiles as The Tenderness of Wolves and Tenderness of the Wolves. In the contextual material on this Blu-ray release, Stephen Thrower talks about these two different English-language titles: the former is the title by which the film was originally submitted to the BBFC, whilst the latter is the title that appeared on a ‘homemade’ poster and which graced the film’s Anchor Bay DVD release in 1999. The film was released by the BFI/Argos Films’ Connoisseur Video label as The Tenderness of Wolves during the 1990s, and as that was my first exposure to the film and the only copy I had owner prior to this new release from Arrow, I did a double take when Arrow’s Blu-ray release (under the title Tenderness of the Wolves) appeared; though as Thrower notes, both versions of the title are a fair enough translation of the original German title, Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe. The film is uncut and runs for 82:11 mins.

Video

This 1080p presentation of Tenderness of the Wolves uses the AVC codec and is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. The film has been restored in 2k from the original negative by the Fassbinder Foundation, and that restoration is the source for this presentation. The film’s previous DVD release from Anchor Bay was in the slightly narrower ratio of 1.66:1; the difference is negligible, and the 1.78:1 ratio on this Blu-ray presentation seems fine. This 1080p presentation of Tenderness of the Wolves uses the AVC codec and is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. The film has been restored in 2k from the original negative by the Fassbinder Foundation, and that restoration is the source for this presentation. The film’s previous DVD release from Anchor Bay was in the slightly narrower ratio of 1.66:1; the difference is negligible, and the 1.78:1 ratio on this Blu-ray presentation seems fine.

The colour photography, by celebrated German cinematographer Jürgen Jürges, is excellent throughout, making strong use of light and shadow and evidencing some interesting compositions: for example, Jürges often composes images like diptychs, with characters standing on either side of the frame and the screen bisected by objects, doorframes or corners of buildings/walls. This Blu-ray presentation of the film demonstrates a superb level of detail which is especially noticeable in close-ups. The film often features shots in which characters are framed by darkness, with the shadows towards the edges of the frame acting almost like a vignette. (In his interview on this disc, Jürges discusses his use during the shooting of the film of Inky lights - which allow a greater sense of directional lighting - instead of the more modern panel lights, in homage to the films of the 1930s; this was something which apparently caused much consternation with Fassbinder, who initially baulked at the Inkys and their tripods littering the set.) Contrast levels are superb, communicating these shots very well and offering a nicely balanced image. The film’s many low light sequences are handled effectively. The encode to disc is, characteristically for Arrow, a strong one, and the presentation has the texture of 35mm film. In all, it’s a very pleasing, organic and filmlike presentation.    NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented, in German naturally, by a LPCM 1.0 mono track that is accompanied by optional English subtitles which are easy to read and grammatically correct. The mono track is clean and clear, and it is also deep and resonant, especially in sequences which feature the use of classical music.

Extras

- Audio commentary with Ulli Lommel. Speaking in English, Lommel provides a commentary that is moderated by Uwe Huber. He discusses in some detail Jürges’ work as the film’s director of photography, and reflects on his association with Fassbinder. He also talks at some length about the locations and sets used for the film, and its very careful production design – including Raab’s obsession with the use of Catholic symbols which was ‘carried into the movie sets’. - Audio commentary with Ulli Lommel. Speaking in English, Lommel provides a commentary that is moderated by Uwe Huber. He discusses in some detail Jürges’ work as the film’s director of photography, and reflects on his association with Fassbinder. He also talks at some length about the locations and sets used for the film, and its very careful production design – including Raab’s obsession with the use of Catholic symbols which was ‘carried into the movie sets’.

- Introduction by Ulli Lommel (0:27). ‘I want you to enjoy this movie. It’s an awesome movie’, Lommel advises the viewer. - ‘Ulli Lommel – The Tender Wolf’ (25:05). This new interview with Lommel sees the director reflecting on his working relationship with Fassbinder, and discussing how Lommel came to direct Tenderness of the Wolves. Lommel talks about Fassbinder’s dissatisfaction with Jürgen Jürges – largely owing to Jürges’ stammer. However, Lommel praises Jürges’ work on the film. Lommel also discusses Kurt Raab’s work on the script and Raab’s performance as Haarmann. Raab apparently disliked Lommel’s suggestion that Raab shave his head to play Haarmann. Lommel also talks about shooting what he suggests are around fifteen minutes of scenes which were not scripted but were inspired by the cinematic locations in which the production took place. He bemoans the tendency for modern cinema to ‘always need to be explained with words, especially in Hollywood’. Lommel says that stories told from the perspective of the police ‘are so fucking boring, because I don’t give a shit what the police thinks’, and that he prefers stories which take place from the point-of-view of the criminal. He states that ‘I know sympathetic people who are evil; I know very unsympathetic people who are very good people. This means nothing’. Raab, Lommel says, was interested in ‘the Christian angle’ introduced in the script but this was something with which Lommel was utterly disinterested. The interview with Lommel is in English.  - ‘Photographing Fritz: How to Shoot a Mass Murderer - Interview with Cinematographer Jürgen Jürges’ (24:24). In this new interview, Jürgen Jürges discusses how he came to be associated with the production of Tenderness of the Wolves. He discusses working with Lommel and Fassbinder. Jürges discusses the use of light within the film, which was achieved with very little but was shaped by close study of films such as Lang’s M. Jürges used the old-fashioned ‘Inkys’ (150 Watt small Fresnel spot lights) rather than the more modern panel lights – which in Jürges’ words were ‘too flat’ for the purposes of shooting the film. Jürges found the Inkys gave him more directionality with the lighting, allowing him to light the eyes or faces of characters and allow the rest of their surroundings to fall off into shadow. However, Fassbinder disliked Jürges’ use of Inkys and the preponderance of their tripods on the set. This interview is in German, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Photographing Fritz: How to Shoot a Mass Murderer - Interview with Cinematographer Jürgen Jürges’ (24:24). In this new interview, Jürgen Jürges discusses how he came to be associated with the production of Tenderness of the Wolves. He discusses working with Lommel and Fassbinder. Jürges discusses the use of light within the film, which was achieved with very little but was shaped by close study of films such as Lang’s M. Jürges used the old-fashioned ‘Inkys’ (150 Watt small Fresnel spot lights) rather than the more modern panel lights – which in Jürges’ words were ‘too flat’ for the purposes of shooting the film. Jürges found the Inkys gave him more directionality with the lighting, allowing him to light the eyes or faces of characters and allow the rest of their surroundings to fall off into shadow. However, Fassbinder disliked Jürges’ use of Inkys and the preponderance of their tripods on the set. This interview is in German, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Love Bitten: Haarman's Victim Talks - Interview with Actor Rainer Will’ (16:07). In yet another new interview, Rainer Will discusses his role in the film as one of the victims of Haarmann. Will was seventeen at the time, and this was his first screen acting job. Will says that he never saw a script and that his scene was added during production by Kurt Raab. He reflects on Raab’s ‘passion for theatre and film’. Raab was also fascinated by religion and faith, and Will suggests that in all Raab’s passions ‘he was haunted by a guilty conscience’. Will also discusses the question of the film’s authorship. This interview is also in German, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Tenderness of Wolves: An Appreciation by Stephen Thrower’ (41:13). Saying that Lommel is a very ‘interesting’ and ‘unusual’ direction, Thrower reflects on Lommel’s career in both Germany and America. He discusses the ‘overlap’ between Fassbinder’s early films and Tenderness of the Wolves. Thrower talks about Lommel’s first film Haytabo (1971) in some detail. He examines the diversity of Lommel’s work and pooh-poohs the suggestion that owing to the perception of some of Lommel’s more recent films as being ‘so poor’, Lommel ‘couldn’t have directed Tenderness of the Wolves’ – that Fassbinder directed the film, rather than Lommel. Thrower argues that a viewing of Haytabo will prove this to be false.  Thrower argues that the film’s focus on homosexuality made it difficult to market in some territories, and he discusses the double standard in terms of the commercial acceptance of films about serial killers who attack women, but the taboo nature of films about homosexual serial killers – especially if the films feature male nudity. The suggestion, Thrower argues, ‘is anything to do with gays is worse than serial killers’. On the other hand, Thrower argues that Tenderness of the Wolves was released uncut in the UK because it was both subtitled and ‘had the authority of a Fassbinder production’. Thrower argues that the film’s focus on homosexuality made it difficult to market in some territories, and he discusses the double standard in terms of the commercial acceptance of films about serial killers who attack women, but the taboo nature of films about homosexual serial killers – especially if the films feature male nudity. The suggestion, Thrower argues, ‘is anything to do with gays is worse than serial killers’. On the other hand, Thrower argues that Tenderness of the Wolves was released uncut in the UK because it was both subtitled and ‘had the authority of a Fassbinder production’.

- Stills Gallery (28 images). - Trailer (3:05). The disc is contained within an Amaray case which has reversible sleeve artwork. Included in the case is one of Arrow’s attractive booklets. This one contains an essay about the film, ‘Murderous Passions’, by Tony Rayns. Rayns suggests that Kurt Raab is the film’s ‘true’ author, and he reflects on Tenderness of the Wolves’ relationship with Effi Brest, he film that Fassbinder was directing at the same time. There’s some detailed examination of the facts of the Fritz Haarmann case, and the ways in which the film’s budget hampered any attempt to ‘recreate a period setting on any scale’. Rayns also suggests that to some extent, Raab’s characterisation of Haarmann was based on the qualities of Fassbinder's own personality. EDIT. The disc contains an 'easter egg' too. On the 'Special Features' menu, highlight 'An Appreciation by Stephen Thrower', press right and right again to hear a rendition of one of the versions of the 'Haarmann Song', based on the tune of an operetta by Walter Kollo.

Overall

Tenderness of the Wolves is a haunting, unsettling and, as the narrative progresses, increasingly disturbing film. Its sense of liminality – its awareness of history but its vague, perhaps even dreamlike depiction of it – ensures that the picture lingers in the mind. This is aided by an intense performance from Raab as Fritz Haarmann and Jürges’ superb photography. Arrow’s Blu-ray release of the film is underpinned by a very handsome presentation of the film itself and some excellent contextual material; it thus comes with a strong recommendation. Tenderness of the Wolves is a haunting, unsettling and, as the narrative progresses, increasingly disturbing film. Its sense of liminality – its awareness of history but its vague, perhaps even dreamlike depiction of it – ensures that the picture lingers in the mind. This is aided by an intense performance from Raab as Fritz Haarmann and Jürges’ superb photography. Arrow’s Blu-ray release of the film is underpinned by a very handsome presentation of the film itself and some excellent contextual material; it thus comes with a strong recommendation.

References: Halle, Randall, 2006: ‘From perverse to queer: Rosa von Praunheim’s films in the liberation movements of the Federal Republic’. In: Clarke, David (ed), 2006: German Cinema: Since Unification. London: Continuum: 207-32 Hutchings, Peter, 2009: The A to Z of Horror Cinema. London: The Scarecrow Press Reimer, Robert C & Reimer, Carol J, 2010: The A to Z of German Cinema. London: The Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|