|

|

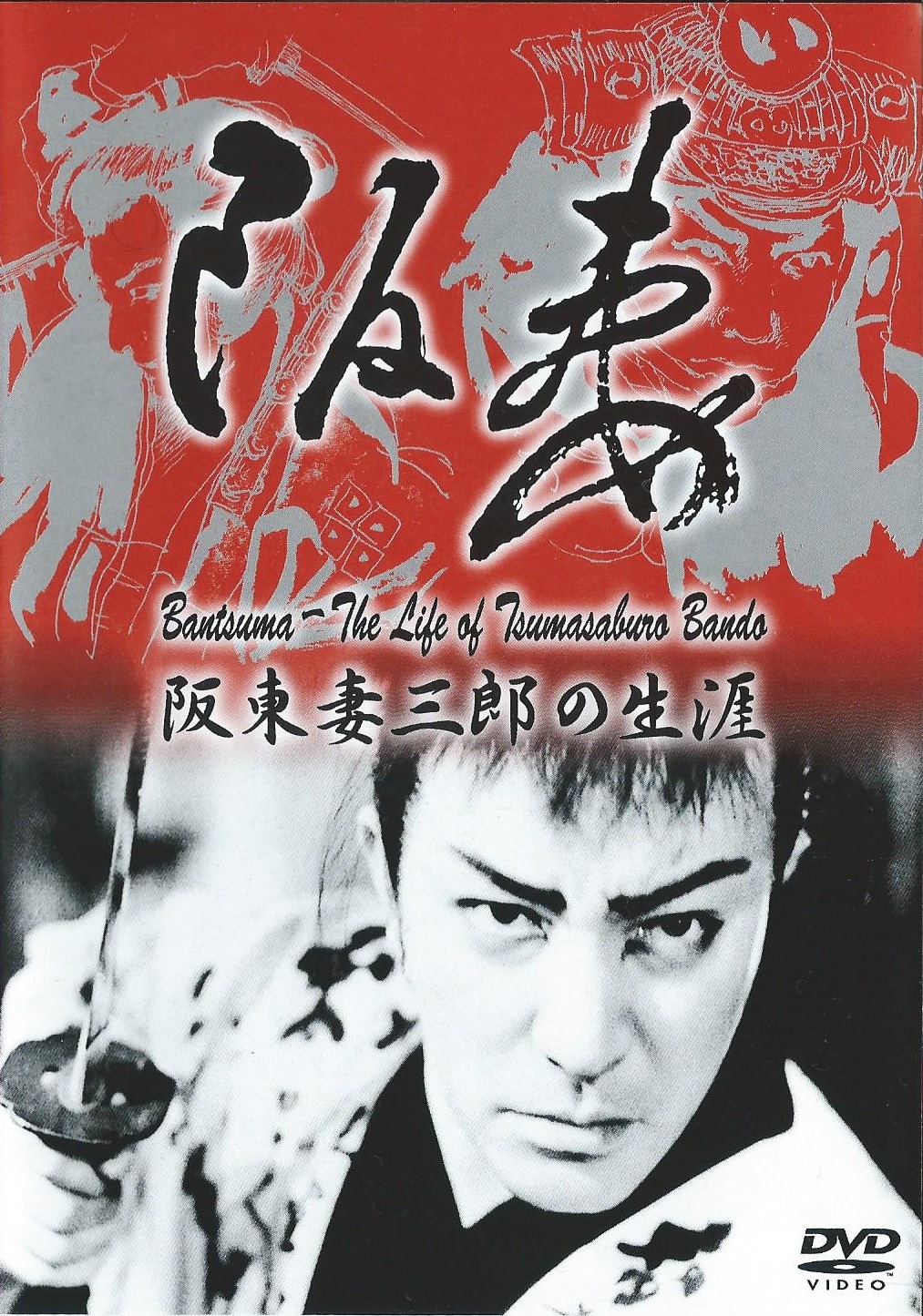

Bantsuma - The Life of Tsumasaburo Bando AKA Bantsuma - Bando Tsumasaburo no shogai

R0 - Japan - Digital Meme Review written by and copyright: James-Masaki Ryan (9th November 2015). |

|

The Film

"Bantsuma - The Life of Tsumasaburo Bando" (1980) Tsumasaburo Bando had quite an extraordinary life in cinema, accomplishing an incredible amount of work both in front of the cameras and behind the scenes, and balancing a family life. It was all too tragic when he died at the age of only 51 years old. Born as Denkichi Tamura at the turn of the 20th century on December 13th, 1901 in Tokyo, Japan, Bando joined Makino Film Productions in 1923 and rose gradually to stardom in jidaigeki (Japanese period films) usually playing heroic samurai characters. Highly influenced by the swashbuckling pirate films and stunt choreography of the Hollywood films of Douglas Fairbanks, Bando took swordplay action to new heights in Japanese cinema. But it wasn’t only his action scenes that proved popular, but also his expressive acting and great scripts penned by his good friend at Makino Film Productions, screenwriter Rokuhei Susukita. His career surges higher in the following years quickly: In 1925, Bando establishes his own production company, “Bantsuma Productions” and he builds his own film studio in Kyoto in 1926. But not all goes well for Bando in subsequent years: A planned partnership with Universal Studios in Hollywood is scrapped before any productions are greenlit, his films in the early 1930’s were not as successful in bringing audiences to the theaters as his earlier works, and his first talkie film in 1935 proved his voice did not match up to the expected power of his decade plus worth of performances. After shutting the doors to his own production company, he became a contract player for Nikkatsu Studios, which fortunately revived his career to an extent, but nothing close to the stardom of the early days. His death in 1953 was just around the time that Japanese cinema was starting to be noticed by the west, with Akira Kurosawa’s “Rashomon” in 1951, Teinosuke Kinugasa’s 1953 spectacle of color “Gate of Hell”, and Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 film “Ugetsu” all receiving international awards, and all three either winning or were nominated for Academy Awards in Hollywood. It seems Bando’s chance for international stardom was Unfortunately right at the time of his death. Born the year Bando starred and produced the landmark and also controversial film “Serpent AKA Orochi” in 1925, Shunsui Matsuda was highly inspired to become a benshi, a narrator of Japanese silent films. During the silent era in Japan, silent films were not only accompanied by music but also by a narrator, who would do voices of characters, read the intertitles, and put a little spin on the films of their own. At the time there were even rankings for the most popular benshi at theaters, and often people would go to specific theaters just to hear their favorite benshi, in addition to caring for the people on the screen. Matsuda was too young to be a benshi during the silent era, but in post-war Japan in which “new” film was limited, Matsuda became a traveling benshi in Kyoto by performing with old silent films. With old films being discarded and forgotten about, it became his quest to collect old films for archival purposes, which he founded "Matsuda Film Productions",, specializing in collecting and preserving film and benshi culture. In order to preserve the legacy of Tsumasaburo Bando, one of the most popular but ultimately forgotten silent Japanese stars, Matsuda produced the documentary entitled “Bantsuma - The Life of Tsumasaburo Bando” in 1980. Working with famed film critic Tadao Sato on the film’s narrative construction rather than established screenwriters, Matsuda directed and partially narrated the film, which includes interviews conducted by Sato, interviewing people such as Bando’s oldest son Takahiro Tamura who also went on to become a popular actor appearing in films such as “Twenty Four Eyes” (1954) the “Miyamoto Musashi” 5 film series (1961-1965), “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970) and “Empire of Passion” (1978). In addition surviving costars such as Shizuko Mori and Utako Tamaki are interviewed. Mori starred in more than 20 films with Bando, including “Kosuzume Pass” (1923), currently the earliest surviving film featuring Bando, and the aforementioned “Serpent AKA Orochi” (1925). Tamaki also starred in “Serpent AKA Orochi” (1925) and starred with Bando for more than 20 films as well. Also interviewed is director Hiroshi Inagaki, who first directed Bando in the 1937 “Hiryu no ken” and in the controversially censored “Jigoku no Mushi AKA Hell Worms” (1938) and in 10 more films pre-war and post-war. Inagaki was most famous in the west for directing the “Miyamoto Musashi Samurai Trilogy” (1954-1956) starring Toshiro Mifune as the title character, in which the first film won the US Academy Award for “Best Foreign Language Film”. The film moves in a linear fashion, starting from Bando’s birth and his childhood to his film career, family life, and death. It is a frequent mix of conducted interviews, photographs, posters, home movies, and clips of Bando’s filmwork from the archives of Matsuda Film Productions, with narration by director Matsuda filling in the gaps like a great benshi would. As valuable information as the film is to piece together his life, one negative setback is that the film relies almost too much on the rare surviving film clips, rather than the words of the people that knew him or from critics. With about half of the movie being footage of films being played out in entire scenes (as well as the beginning and ending of “Backward Flow AKA Gyakuryu” being played, spoiling the bloody finale. From the standpoint of when the film was made in 1980 being rare for anyone in the world to see any of Bando’s films, so the decision was not for pacing or artistic reasons but for the primary reason that no one could see these clips otherwise. Also prominently missing was input from critic Tadao Sato, who is seen in the film asking questions, but is curiously not giving his own input at all. It probably would have worked a little better if the film was less reliant on the long film clips and more toward interviews, but considering that many that had worked with Bando in the past had long passed away by 1980, audiences should be glad that at least there are interviews included with people who he had worked with, cementing his legacy for future generations of film watchers. The film was completed and copywritten in 1980, though it was not shown in Japan until 1993. Prior to its screenings in Japan, it was featured at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1988, and later at the Sao Paolo International Film Festival, London International Film Festival, and the Bombay International Film Festival. Initially the film was to be screened as a short film with the 1979 Matsuda Film Productions film “Jigoku no Mushi AKA Hell Worms”, a remake of the 1938 film directed by Hiroshi Inagaki and starring Bando and also with future Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura. But when it was realized that a short film was not enough to fully tell the life and work of Bando, the film was lengthened to a feature length, and also led to financial difficulty. Note: This is a region 0 NTSC DVD and can be played back on any DVD player worldwide.

Video

Digital Meme presents the film in its original non-anamorphic 1.33:1 aspect ratio in the NTSC format. The print was taken from a standard definition master from the Matsuda Film Productions archives which has its limitations. First off the interview segments look average at best. Colors are slightly faded looking but sharpness is fine. These are not professionally lit studio settings but in locations such as the interview subjects’ homes shot on film. The black and white vintage film clips are varying in quality. All clips have the usual problems of scratches, tramlines, stability problems, off centered framing, and missing frames. Compared side by side with some of the films released in the Digital Meme “Talking Silents 3” and “Talking Silents 4” DVD sets, the source materials are the same (coming from the Matsuda Film Productions archives) but it is clear that the “Talking Silents” sets are remastered with digital technology while the clips in the “Bantsuma” film is “as is” since digital restoration was not available in 1980. Though it should be noted that it preserves how the film looked at the time. With still photographs there is chroma noise, which seems to be inherent to the original film source as those are the only instances of chroma. The interview segments and vintage film clips feature no such problem. Overall, it is a tad under average transfer, nothing groundbreaking, but nothing overall distractingly bad.

Audio

There is only one audio track: Japanese Dolby Digital 2.0 dual mono. The narration by the director Shunsui Matsuda and select portions by famed benshi Midori Sawato sound fine, while there are some issues with a few of the interviews. Soundwise there isn’t a problem, but the synching is way off in some portions that it looks like a badly dubbed film, while other portions the lipsynching is a split second off, which is noticeable. These seem to be inherent to the original film and not due to the DVD transfer. The vintage talkie film segments have fidelity issues and hisses and pops are frequent. Again, digital sound restoration was not present in 1980 and is presented as is. There are optional English and Japanese subtitles for the film. Both are in a white font, the English is easy to read with no errors, translating all dialogue and captions.

Extras

Profiles (text screens) - Takahiro Tamura - Shizuko Mori - Utako Tamaki - Daisuke Ito - Hiroshi Inagaki - Ryu Kuze - Tadao Sato - Shunsui Matsuda - Midori Sawato The biography text screens of the participants and filmmakers are presented in Japanese on Japanese menu screens and in English on English menu screens. Bantsuma Digital Album (slideshow) - Play All (9:45) - Private Shots of Bantsuma (2:11) - Silent Films (2:36) - Talkie Films (1:46) - Posters and Magazine Covers (1:51) - Bantsuma Illustrations (by Shogo Okamoto) (1:21) A collection of photos, posters, and more from the Matsuda Film Productions archives. These play automatically with musical accompaniment. The film stills have Japanese and English text to caption which films and which years they were made. 14 page booklet The booklet is bilingual, with half in Japanese and half in English. Included are 2 essays by Yutaka Matsuda of Matsuda Film Productions and benshi Midori Sawato, cast & crew listing, and excerpts from articles written by Tsumasaburo Bando for vintage film magazines. It would have been great if the 1979 production of "Hell Worms" was included with the documentary here as a double feature, as originally intended. Unfortunately, there still isn't a DVD release of "Hell Worms" for all to see. The original 1938 film, the truncated version is considered lost. It also would have been nice to hear from Tadao Sato who has contributed to the "Talking Silents" DVD sets in the bonus features. About his personal thoughts of Bando and the films, as well as how it was conducting interviews and how the film grew from short to feature.

Overall

Tsumasaburo Bando was undoubtedly one of the most important and one of the most popular figures in Japanese cinema history who has ultimately been forgotten by the mainstream. Though his blood still remains strong in entertainment, as his oldest son interviewed in the documentary Takahiro Tamura (who died in 2006), his third son Masakazu Tamura, fourth son Ryo Tamura, fifth son Yasuhiro Minakami, and grandson Koji Tamura have continued work in television and cinema. (The second son became Takahiro and Masakazu’s manager.) It’s a bit hard to recommend the documentary on its own as it works better as a supplement rather than a standalone film. If you haven’t watched any films starring Bando before, it is recommended to watch the 4 films in the “Talking Silents 3” and “Talking Silents 4” sets first. Of course, very recommended for silent cinema fans. The DVD can be purchased on Amazon Japan or through Digital Meme’s website directly.

|

|||||

|