|

|

Ladykillers (The) AKA The Lady Killers (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Studio Canal Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th November 2015). |

|

The Film

The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955)  Alexander Mackendrick’s delicious black comedy The Ladykillers (1955), Mackendrick’s last British film and one of Ealing’s most highly-regarded comedy pictures, focuses on Mrs Wilberforce (Katie Johnson). Mrs W, as she comes to be known within the film itself, is approached by the shady Professor Marcus (Alec Guinness) about the rooms that she has available to rent within her house. Marcus claims to be part of a group of amateur musicians and asks Mrs W if it is permissible to invite the other members of his string quintet to the house to practice: the members of his group include Major Courtney (Cecil Parker), Mr Lawson (Danny Green), Mr Robinson (Peter Sellers) and Mr Harvey (Herbert Lom). However, unbeknownst to Mrs W, these men are in fact criminals. They are planning a heist, and hope to use the innocent Mrs W to help them to move the money once they have stolen it. Alexander Mackendrick’s delicious black comedy The Ladykillers (1955), Mackendrick’s last British film and one of Ealing’s most highly-regarded comedy pictures, focuses on Mrs Wilberforce (Katie Johnson). Mrs W, as she comes to be known within the film itself, is approached by the shady Professor Marcus (Alec Guinness) about the rooms that she has available to rent within her house. Marcus claims to be part of a group of amateur musicians and asks Mrs W if it is permissible to invite the other members of his string quintet to the house to practice: the members of his group include Major Courtney (Cecil Parker), Mr Lawson (Danny Green), Mr Robinson (Peter Sellers) and Mr Harvey (Herbert Lom). However, unbeknownst to Mrs W, these men are in fact criminals. They are planning a heist, and hope to use the innocent Mrs W to help them to move the money once they have stolen it.

The heist goes to plan, and unaware of her role in the gang’s scheme, Mrs W inadvertently helps them to transport the stolen money from the King’s Cross to the gang’s hideout at Mrs W’s house. However, Lawson accidentally makes Mrs W aware of the true nature of her new guests, and though Marcus attempts to persuade Mrs W that the stolen money is insured and will go unmissed, the gang come to the conclusion that Mrs W must be eliminated. This plan goes awry, and one by one the members of Marcus’ criminal enterprise only succeed in eliminating themselves. Barry Forshaw has stated that The Ladykillers ‘is as black a comedy as one could wish, with the death of virtually its entire male cast still shocking in an era when wholesale carnage is hardly novel’ (Forshaw, 2012: 100). Forshaw suggests that the ‘bleak and cynical’ humour of the film is complemented by Mackendrick’s next film, the utterly dark American film noir Sweet Smell of Success (1957). With the knowledge that The Ladykillers was Mackendrick’s last British film before he moved to America, Anthony Aldgate and Jeffrey Richards argue, ‘[i]t is hard […] to see The Ladykillers as anything other than an irreverent farewell to England – that England of the Conservative mid-1950s that has been characterized by Arthur Marwick as suffering from “complacency, parochialism, lack of serious, structural change”’ (Aldgate & Richards, 2002: 159, quoting Marwick). The film offers a ‘sardonic recognition of the impossibility of change’ in both mid-1950s England and within Ealing Studios itself, whilst also recognising the preference within the paradigms associated with Ealing for ‘the small and the old’: ultimately, Aldgate and Richards argue, ‘[w]hether you take the film as a critique or as a celebration of that ethos, however, depends entirely on your point of view’ (ibid.).  Philip Kemp has suggested that Mackendrick’s films operated within the paradigms established within Ealing’s other pictures, especially their comedies, but subtly challenged them too (Kemp, cited in Shail, 2005: 303). The Ladykillers is a strong example, following the formula of other Ealing comedies whilst deviating from that formula in some notable ways. As in many of the Ealing comedies, The Ladykillers evidences a vein of realism ‘in the use of location shooting, the strong sense of place and the focus on ordinary citizens’ but this is offset by ‘fantasy and visual stylisation’ (ibid.: 302). Philip Kemp has suggested that Mackendrick’s films operated within the paradigms established within Ealing’s other pictures, especially their comedies, but subtly challenged them too (Kemp, cited in Shail, 2005: 303). The Ladykillers is a strong example, following the formula of other Ealing comedies whilst deviating from that formula in some notable ways. As in many of the Ealing comedies, The Ladykillers evidences a vein of realism ‘in the use of location shooting, the strong sense of place and the focus on ordinary citizens’ but this is offset by ‘fantasy and visual stylisation’ (ibid.: 302).

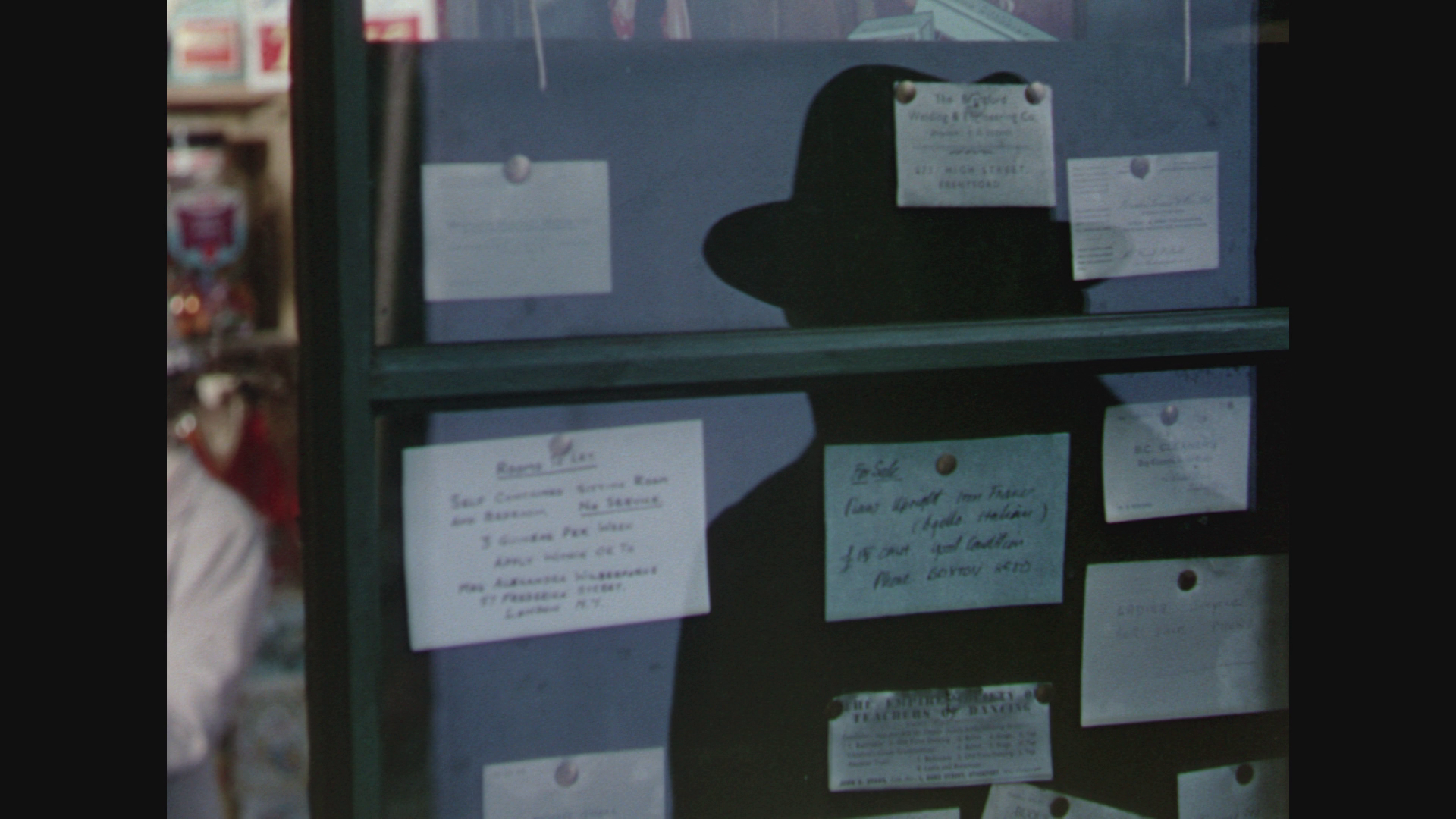

There’s stark contrast between The Ladykillers and one of Ealing’s other crime-themed films, The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951), which like The Ladykillers revolves around a carefully planned heist and features a gang of criminals. Charles Barr has argued that The Lavender Hill Mob, along with Mackendrick’s Whisky Galore (1949), forms part of ‘the set of Ealing comedies that enlist our sympathy with a form of law-breaking’ (Barr, quoted in Geraghty, 2002: 69). The film is ‘a form of daydream’ in which order is restored through a moral ending and the comedy ‘which imagines an escape from that morality without the risks involved’ (ibid.). By contrast, Christine Geraghty says, The Ladykillers is ‘rather tougher’, featuring a gang which represents various types within society: ‘the fiendishly clever professor with his confident Establishment manners’; ‘an upper-class ex-officer who is sliding down the social scale’; the ‘working-class One-Round claiming his rights to be counted’; a ‘representative of modern youth’, Harry Robinson; ‘and even a foreigner, the ruthless Louis’ (ibid.). Played wonderfully by Guinness, Marcus is introduced as, shown only in shadow and silhouette, he follows Mrs W home before ringing her doorbell. His manners too polite and deferential, his insincerity is signaled to the audience from the outset – though Mrs W’s innocent worldview obscures her from a true perception of Marcus. Marcus, it seems, has adopted the title ‘professor’ as a badge of respectability: in a later scene, Robinson refers to Marcus as ‘doctor’, but Marcus corrects him, telling Robinson he must remember that this time, he is known as ‘Professor Marcus’. The criminal endeavours of this group, represented through their big heist, are thwarted ‘not by the law but by “the Nannyish authority and the Victorian Baggage”’ represented through Mrs Lopsided (ibid., quoting Charles Barr).  Robert Shail notes that with the arrival of Marcus and his gang at Mrs W’s house, The Ladykillers ‘abandons Ealing’s usual reliance on surface realism and adopts a stylisation which borders on the Gothic’ (Shail, op cit.: 303). Where the majority of Marcus’ gang either bumble into the house (in the case of Lawson and Robinson) or mimic Marcus’ easy manners, as is the case with Courtney), when Harvey is introduced on Mrs W’s doorstep he steps back into the expressionistic shadows, his face hidden from view by them, and clutches his violin case as if it were a Tommy gun. His defensive behaviour leads Marcus to declare to Mrs W that Harvey is the ‘temperamental one’. Mrs W’s house, cluttered and lopsided owing to subsidence, invokes ‘a feeling of claustrophobia, rather than the cosy comfort’ more commonly associated with the Ealing comedies (ibid.). There is, according to Shail, an ‘underlying menace’ within the film which ‘comes to the surface’ in the film’s second half, in which ‘the humour gradually drains out of Rose’s script’ which transforms into ‘a modern morality play, as the criminal gang destroy themselves, leaving the scene scattered with bodies in the manner of a Jacobean revenge tragedy’ (ibid.). Robert Shail notes that with the arrival of Marcus and his gang at Mrs W’s house, The Ladykillers ‘abandons Ealing’s usual reliance on surface realism and adopts a stylisation which borders on the Gothic’ (Shail, op cit.: 303). Where the majority of Marcus’ gang either bumble into the house (in the case of Lawson and Robinson) or mimic Marcus’ easy manners, as is the case with Courtney), when Harvey is introduced on Mrs W’s doorstep he steps back into the expressionistic shadows, his face hidden from view by them, and clutches his violin case as if it were a Tommy gun. His defensive behaviour leads Marcus to declare to Mrs W that Harvey is the ‘temperamental one’. Mrs W’s house, cluttered and lopsided owing to subsidence, invokes ‘a feeling of claustrophobia, rather than the cosy comfort’ more commonly associated with the Ealing comedies (ibid.). There is, according to Shail, an ‘underlying menace’ within the film which ‘comes to the surface’ in the film’s second half, in which ‘the humour gradually drains out of Rose’s script’ which transforms into ‘a modern morality play, as the criminal gang destroy themselves, leaving the scene scattered with bodies in the manner of a Jacobean revenge tragedy’ (ibid.).

Mrs W herself is introduced in a sequence in which she visits the local police station to apologise for her friend, who has previously filed a blatantly false report of an alien spacecraft landing in her back garden (‘It’s about my friend Amelia and the, er, spaceship’, Mrs W says). Her friend, Mrs W suggests, had simply become confused after listening to a radio programme and imagined the whole thing. Mrs W is absolutely correct; her case is stated clearly and logically, and as she states, she simply sees it as her ‘duty to come here and explain’. The police treat Mrs W kindly, accepting her apology, but clearly regard her with amusement and perceive her as a harmless eccentric – when in fact she is as sharp as the proverbial tack. Her home, which as she explains to Marcus is lopsided owing to bombing during the war, is connected to the past via its décor and the objects within it: Claire Mortimer has argued that Mrs W’s house is ‘a museum piece commemorating a bygone age’ and was intended by Mackendrick to be a ‘liminal world’ where the disparate characters (Mrs W and the various members of the gang, representatives of different strata within British society) come together (Mortimer, 2013: 425).  Shail suggests that the film depicts Mrs W ambiguously: where in a more conventional Ealing comedy Mrs W would be presented simply as ‘a loveable old lady’, here she ‘proves to be rather more formidable and destructive than might be expected’ (Shail, op cit.: 304). Philip Kemp has suggested that Mrs W represents both innocence and ‘the past in which England is mired’ (Kemp, quoted in ibid.). Mrs W and her lopsided house are ‘a metaphor for post-war Britain, a place crippled by inertia, clinging to the past and blindly ignoring the fact that the whole construction is falling to bits’ (ibid.). The house, Mrs W declares, is lopsided owing to ‘subsidence […] from the bombing’; the upper floors of the house are ‘structurally unsound’. With their Edwardian fashions, Mrs W and her friends ‘seem to have been preserved from an era before the First World War’ (ibid.). From the outset, Harvey expresses the most displeasure at Mrs W’s role in Marcus’ plot. ‘I tell you, I don’t like old ladies. I don’t like having them around. I can’t stand them’, Harvey complains when Marcus tells the group that ‘Mrs Wilberforce is not an appendage to my plan; she’s the very core of it’. On the other hand, the childlike Lawson admires Mrs W, who he nicknames ‘Mrs Lopsided’ owing to the lopsided nature of her house, acquiescing to her demands and expressing vocal dissatisfaction with the notion put forward by other members of the gang that Mrs W must be killed (‘Nobody touches Mrs Lopsided’, he asserts). Shail suggests that the film depicts Mrs W ambiguously: where in a more conventional Ealing comedy Mrs W would be presented simply as ‘a loveable old lady’, here she ‘proves to be rather more formidable and destructive than might be expected’ (Shail, op cit.: 304). Philip Kemp has suggested that Mrs W represents both innocence and ‘the past in which England is mired’ (Kemp, quoted in ibid.). Mrs W and her lopsided house are ‘a metaphor for post-war Britain, a place crippled by inertia, clinging to the past and blindly ignoring the fact that the whole construction is falling to bits’ (ibid.). The house, Mrs W declares, is lopsided owing to ‘subsidence […] from the bombing’; the upper floors of the house are ‘structurally unsound’. With their Edwardian fashions, Mrs W and her friends ‘seem to have been preserved from an era before the First World War’ (ibid.). From the outset, Harvey expresses the most displeasure at Mrs W’s role in Marcus’ plot. ‘I tell you, I don’t like old ladies. I don’t like having them around. I can’t stand them’, Harvey complains when Marcus tells the group that ‘Mrs Wilberforce is not an appendage to my plan; she’s the very core of it’. On the other hand, the childlike Lawson admires Mrs W, who he nicknames ‘Mrs Lopsided’ owing to the lopsided nature of her house, acquiescing to her demands and expressing vocal dissatisfaction with the notion put forward by other members of the gang that Mrs W must be killed (‘Nobody touches Mrs Lopsided’, he asserts).

For her part, Mrs W’s authority begins to be asserted once she has discovered Marcus’ group’s involvement in the heist, which is set in motion when Lawson accidentally splits open his cello case to reveal the cash stuffed inside it. When, subsequent to this, Mrs W’s friends come to the house for a visit, Mrs W enacts her authority by telling Marcus’ gang to ‘Simply try for one hour to behave like gentlemen’. (‘All right, mum’, Lawson responds to this.) After this, Marcus uses twisted logic to try to persuade Mrs W not to report his gang’s involvement in the heist to the police: ‘it would do no good to take the money back’, Marcus asserts, ‘As strange as it may seem to you, no-one wants the money back [….] You see, the insurance company simply pays to the factory sixty thousand pounds, and in order to recoup its money it puts one farthing on all the premiums, on all the policies for the next year [….] So how much real harm have we done anybody? One farthing’s worth [….] I assure you, if we tried to take the money back now, it would simply confuse the issue’. This bizarre logic is given a moment of comic ‘payoff’ at the end of the film when, the members of the gang having eliminated themselves through a series of mishaps, Mrs W enters the police station and attempts to return the money. In an echo of the film’s first sequence, the policemen, still considering Mrs W to be a harmless eccentric and therefore disbelieving her story, tell her to keep the money. Mrs W repeats Marcus’ reasoning, questioning if returning the money would simply ‘confuse the issue’; the police respond in the affirmative, and as the film closes Mrs W returns home apparently free to keep the stolen sixty thousand pounds.  Charles Barr has suggested that in the triumph of Mrs Wilberforce, who is connected to the past by her reminisces, The Ladykillers ‘show[s] the damaging consequence of the triumph of “the inertia of the status quo”’ (Geraghty, op cit.: 69, quoting Barr). On the other hand, Christine Geraghty argues, the film may be perceived as celebrating, through the victory enacted by Mrs W, ‘tradition and the tenacity of the past’ (ibid.). Mrs W’s victory over the gang ‘is a clear indication of the real power of “old England” to maintain the status quo’ (Shail, op cit.: 304.). In some ways, Mackendrick’s slyly subversive comedy therefore acts as a bridge between the nostalgic impulse within Ealing’s comedies and the later, thoroughly modern British New Wave films (Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top, 1958) and Carry On… pictures (beginning with Carry on Sergeant, also in 1958). Charles Barr has suggested that in the triumph of Mrs Wilberforce, who is connected to the past by her reminisces, The Ladykillers ‘show[s] the damaging consequence of the triumph of “the inertia of the status quo”’ (Geraghty, op cit.: 69, quoting Barr). On the other hand, Christine Geraghty argues, the film may be perceived as celebrating, through the victory enacted by Mrs W, ‘tradition and the tenacity of the past’ (ibid.). Mrs W’s victory over the gang ‘is a clear indication of the real power of “old England” to maintain the status quo’ (Shail, op cit.: 304.). In some ways, Mackendrick’s slyly subversive comedy therefore acts as a bridge between the nostalgic impulse within Ealing’s comedies and the later, thoroughly modern British New Wave films (Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top, 1958) and Carry On… pictures (beginning with Carry on Sergeant, also in 1958).

The film is uncut and runs for 90:21 mins.

Video

This 1080p presentation of The Ladykillers uses the AVC codec.  Like Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of the same title, The Ladykillers is here presented in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio. There’s some debate about this, as given the year of its production it’s possible (or, depending on your point of view, probably) that the film was intended to be exhibited in a slightly wider ratio – most likely 1.66:1 or perhaps even 1.75:1. (The film has been released on DVD in the 1.66:1 ratio, to boot.) It’s also equally likely that given its production on the cusp of the widescreen era, the compositions were ‘protected’ for multiple screen ratios. That said, the 1.37:1 framing on this Blu-ray looks fine: there’s some notable room at the top and bottom of the compositions, but they don’t look distractingly unbalanced. Like Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of the same title, The Ladykillers is here presented in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio. There’s some debate about this, as given the year of its production it’s possible (or, depending on your point of view, probably) that the film was intended to be exhibited in a slightly wider ratio – most likely 1.66:1 or perhaps even 1.75:1. (The film has been released on DVD in the 1.66:1 ratio, to boot.) It’s also equally likely that given its production on the cusp of the widescreen era, the compositions were ‘protected’ for multiple screen ratios. That said, the 1.37:1 framing on this Blu-ray looks fine: there’s some notable room at the top and bottom of the compositions, but they don’t look distractingly unbalanced.

At the bottom of this review there are some large screen grabs comparing this 60th Anniversary Edition release to Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of the film. In playback, there is little discernible difference between the two releases, and both seem to be based on the same source. Both presentations contain a good level of detail and are based on a restoration (documented within the disc’s special features) that has delivered a presentation of the film which is remarkably clean of damage and debris. The Ladykillers was the last film shot in 3-strip Technicolor, and displays the unique look of that film format, complete with its fine grain structure which is rendered nicely within the robust encode on this disc. The restoration apparently struggled to perfectly align the three-strip negatives owing to the shrinkage and warping they had experienced over time, and as a consequence there’s some ‘fringing’ of colour. There’s a bias towards a muted pink within the palette that leads to much of the film having a very ‘rosey’ appearance, and the appearance of this restoration on Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray attracted criticism from some quarters that it’s appearance was too bright and saturated with faded pink. (That said, the ‘rosey’ appearance of the film certainly connects thematically with the dominance of Mrs W within the narrative.) Those displeased with the presentation on Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of this film will remain equally displeased with this new release, which is almost identical. Those who were pleased with the previous Blu-ray release will find this new 60th Anniversary Edition equally satisfying. In comparison with Studiocanal’s earlier Blu-ray release, however, the new 60th Anniversary Edition has contrast levels which are noticeably more balanced.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clean and free of problems, and dialogue is always audible. The track is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

This disc replicates the contextual material found on Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of The Ladykillers and adds a handful of new features. The previously seen special features are:  - an audio commentary with Philip Kemp. Kemp provides a thoroughly well-researched commentary track, packed with information about the production and, especially, about Mackendrick’s approach to filmmaking. - an audio commentary with Philip Kemp. Kemp provides a thoroughly well-researched commentary track, packed with information about the production and, especially, about Mackendrick’s approach to filmmaking.

- an introduction by Terry Gilliam (2:58). This introduction by Gilliam is brief but conveys his profound enthusiasm for the film. Gilliam offers more detailed discussion of the film in the documentary ‘Forever Ealing’, also included on this disc. - the documentary ‘Forever Ealing’ (2002) (49:37). Narrated by Daniel Day Lewis, this superb documentary looks at the history of Ealing Studios and features input from some of the people associated with Ealing, including John Mills and Douglas Slocombe; the documentary also spends some time focusing on the production of Oliver Parker’s The Importance of Being Earnest (2002), which was shot at Ealing Studios, with comments from Rupert Everett and Colin Firth. Interviews with: - Allan Scott (10:30). Scott reflects on Mackendrick’s technique as a filmmaker, offering discussion of Mackendrick’s approach to narrative and his construction of mise-en-scène. - Terence Davies (13:49). Davies, a student of Mackendrick’s, discusses his abiding passion for The Ladykillers and offers some fascinating comments on what he regards as the film’s major focus on the issue of social class. - Ronald Harwood (7:14). Harwood, a friend of Mackendrick’s, discusses his feelings about the film and offers an examination of Mackendrick’s approach to filmmaking. - the featurette ‘Cleaning Up The Ladykillers’ (6:07). This featurette focuses on the restoration of the film and features side-by-side clips to illustrate the work done to the picture. - the film’s trailer (2:34). The new special features are: - a locations featurette (9:27) in which Allan Dein visits some of the locations used during the production of the film. Two lengthy audio interviews: - with Tom Pevsner (91:29). Interviewed here, Pevsner, the assistant film director on The Ladykillers, talks at length about his career and his involvement with the picture. - with David Peers (92:35). In another long interview, the film’s unit production manager, David Peers, discusses his life and his work in the film industry. - a stills gallery (28 images).

Overall

The Ladykillers is a fascinating film. It may be read as a traditionally ‘cosy’ Ealing comedy or, alternatively, as a film which subtly subverts the worldview of Ealing’s other comedies. Certainly, it’s a significant film for both Ealing and The Ladykillers’ director, Alexander Mackendrick. The presentation of the main feature on this new 60th Anniverary Blu-ray release is near-identical to Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of the same title, and will most likely divide opinion in exactly the same ways. There seems to be some evidence that the film was exhibited in 1.66:1 or perhaps even wider, but the 1.37:1 framing here works nicely and it’s likely that the compositions were ‘protected’ for a number of screen formats. The differences in terms of the palette and brightness levels of Studiocanal’s Blu-ray presentations and those of the film’s previous DVD releases are less easy to negotiate, and though certain aspects of the restoration are likely to divide opinion as per Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release, certainly in terms of visible detail both discs are a significant upgrade over the film’s previous DVD releases. With the presentations contained on Studiocanal’s new 60th anniversary Blu-ray release and the company’s older Blu-ray disc having little discernable difference between them, the major incentive to purchase this Blu-ray over the previously available disc is the inclusion of some new contextual material. And that contextual material is very good indeed. The Ladykillers is a fascinating film. It may be read as a traditionally ‘cosy’ Ealing comedy or, alternatively, as a film which subtly subverts the worldview of Ealing’s other comedies. Certainly, it’s a significant film for both Ealing and The Ladykillers’ director, Alexander Mackendrick. The presentation of the main feature on this new 60th Anniverary Blu-ray release is near-identical to Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release of the same title, and will most likely divide opinion in exactly the same ways. There seems to be some evidence that the film was exhibited in 1.66:1 or perhaps even wider, but the 1.37:1 framing here works nicely and it’s likely that the compositions were ‘protected’ for a number of screen formats. The differences in terms of the palette and brightness levels of Studiocanal’s Blu-ray presentations and those of the film’s previous DVD releases are less easy to negotiate, and though certain aspects of the restoration are likely to divide opinion as per Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release, certainly in terms of visible detail both discs are a significant upgrade over the film’s previous DVD releases. With the presentations contained on Studiocanal’s new 60th anniversary Blu-ray release and the company’s older Blu-ray disc having little discernable difference between them, the major incentive to purchase this Blu-ray over the previously available disc is the inclusion of some new contextual material. And that contextual material is very good indeed.

References: Forshaw, Barry, 2012: British Crime Film: Subverting the Social Order. London: Palgrave Macmillan Geraghty, Christine, 2002: British Cinema in the Fifties: Gender, Genre and the New Look. London: Routledge Mortimer, Claire, 2013: ‘Alexander Mackendrick: Dreams, Nightmares, and Myths in Ealing Comedy’. In: Horton, Andrew & Rapf, Joanna (eds), 2013: A Companion to Film Comedy. London: John Wiley and Sons: 409-31 Shail, Robert, 2015: ‘The Ladykillers’. In: Barrow, Sarah et al (eds), 2015: The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films. London: Routledge: 302-5 Aldgate, Anthony & Richards, Jeffrey, 2002: Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to the Present. London: I B Tauris Comparison with Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray release. Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray:

60th Anniversary Edition:

Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray:

60th Anniversary Edition:

Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray:

60th Anniversary Edition:

Studiocanal’s previous Blu-ray:

60th Anniversary Edition:

More grabs from the new 60th Anniversary Blu-ray release:

|

|||||

|