|

|

Wake Up and Kill AKA Svegliati e uccidi AKA Wake Up and Die (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th November 2015). |

|

The Film

Wake Up and Kill AKA Svegliati e uccidi AKA Wake and Kill AKA Wake Up and Die (Carlo Lizzani, 1966) Wake Up and Kill AKA Svegliati e uccidi AKA Wake and Kill AKA Wake Up and Die (Carlo Lizzani, 1966)

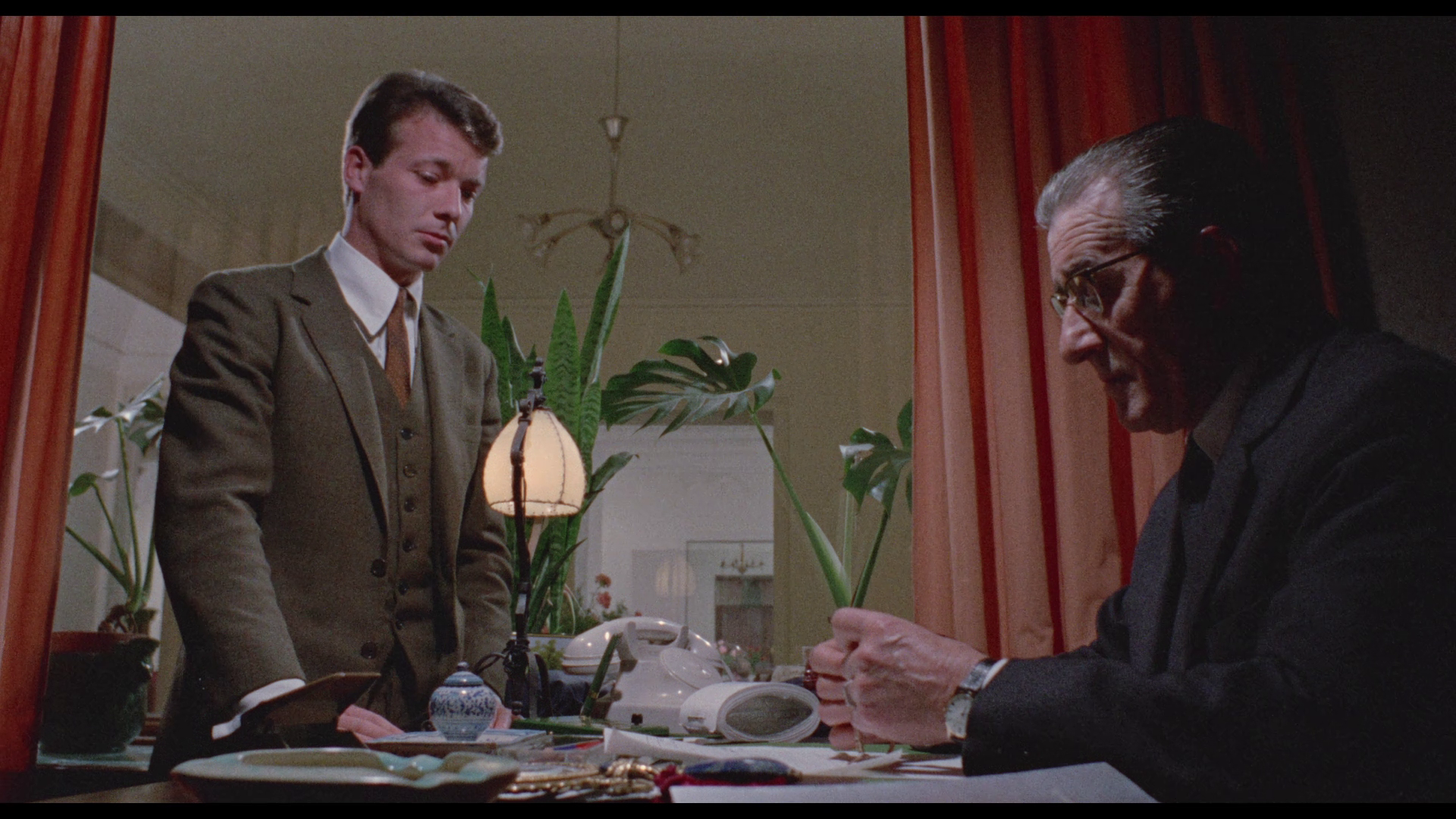

Luciano Lutring (Robert Hoffmann), the son of a grocer and a petty thief, becomes involved with Yvonne (Lisa Gastoni), a nightclub singer who prefers to be known as ‘Candida’. Yvonne is the former moll of known gangster Franco Magni (Claudio Camaso). Desperate to impresse Yvonne, Lutring graduates from car theft to committing smash-and-grab raids on jewelers’ shops, breaking the windows with an axe before stealing whatever he can from the display. Yvonne marries Lutring, but only on an empty promise that he will abandon his criminal ways. However, pledged to give Yvonne the high life, Lutring’s criminal method evolves; when, on a quiet news day, the city’s newspaper decides to make Lutring’s crimes headline news, making Lutring a fugitive from the law, Lutring discovers that the cost of a bed for the night escalates from 2,000 lire to 50,000 lire. Lutring becomes involved in orchestrating more complex robberies. However, he is an outsider to the criminal fraternities that exist within Milan, and when he approaches one group with a potentially big score in the centre of Milan, they decide to frame him. Lutring escapes, barely, but hot on his tail is Inspector Moroni (Gian Maria Volonte). Moroni appeals to Yvonne to ‘shop’ her husband, reasoning that Lutring’s escalation, his naïveté and his increasing reliance on guns will, if he is left on the streets, inevitably lead to his death either at the hands of the police or the gangsters with whom Lutring is coming into contact.  Now drinking heavily and having taken to carrying a machine gun on his robberies (with the press dubbing him the ‘machine gun soloist’ owing to his tendency to carry the gun in a violin case), Lutring flees to Paris, where he becomes involved with an Algerian and a Corsican. The trio organise a heist on the Cote d’Azur, which results in the death of a policeman. Finding it impossible to sell the proceeds of this robbery and his weapons having been seized, Lutring flees by train back to Milan, where he makes contact with Yvonne, before returning to Paris one more time. Now working for Inspector Moroni, Yvonne travels to Paris, and Moroni becomes involved in a dispute over jurisdiction with Parisian Inspector Julien (Ottavia Fanfani). Now drinking heavily and having taken to carrying a machine gun on his robberies (with the press dubbing him the ‘machine gun soloist’ owing to his tendency to carry the gun in a violin case), Lutring flees to Paris, where he becomes involved with an Algerian and a Corsican. The trio organise a heist on the Cote d’Azur, which results in the death of a policeman. Finding it impossible to sell the proceeds of this robbery and his weapons having been seized, Lutring flees by train back to Milan, where he makes contact with Yvonne, before returning to Paris one more time. Now working for Inspector Moroni, Yvonne travels to Paris, and Moroni becomes involved in a dispute over jurisdiction with Parisian Inspector Julien (Ottavia Fanfani).

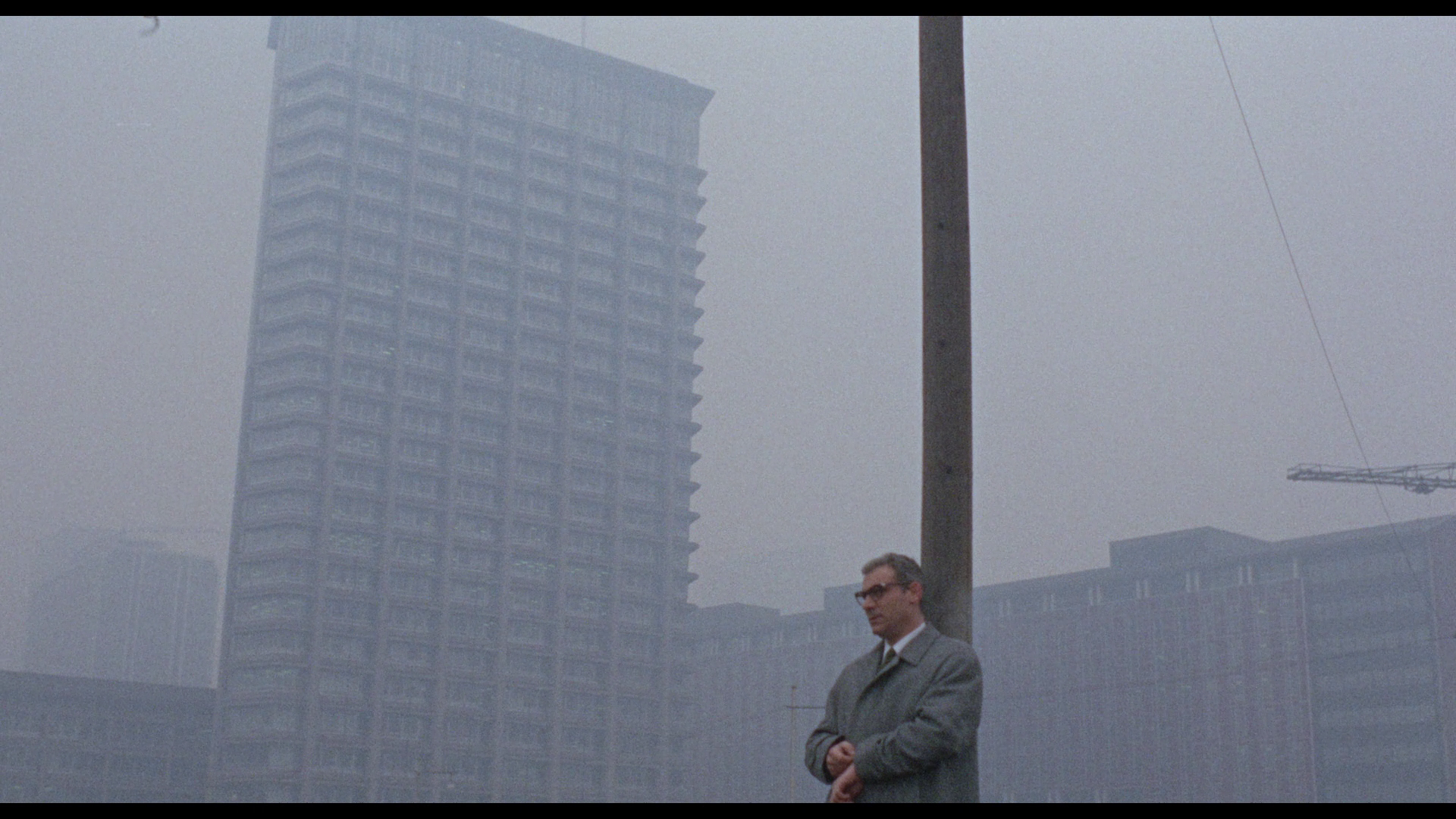

A precursor in many ways to the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style cop film, sometimes discussed by English-speaking fans under the originally pejorative denominator poliziotteschi) which became popular during the years of social turmoil in Italy (the anni di piombo) that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing in 1969, Carlo Lizzani’s Svegliati e uccidi (1966) anticipates the films about banditi (bandits) that would during the 1970s become a key part of the poliziesco subgenre. The first poliziesco picture ‘proper’ – in other words, the film which is seen as establishing the defining paradigms of the poliziesco films of the 1970s – is often suggested to be Steno’s La polizia ringrazia (Execution Squad, 1972), but the subgenre has its roots in earlier trends within Italian cinema: principally, the cine-inchieste (semidocumentary ‘investigation’ films) such as Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962).  During the 1960s, the Italian crime film had a short history, but it was one which was closely allied with the concept of socially-minded cinema, with the pictures often being made by filmmakers whose worldview leant strongly towards the political left. In part, this may be because under the Fascist regime during the pre-war period, the production of crime films had been prohibited (or at the very least, frowned severely upon) owing to the perception that they highlighted the fissures within society – something which, obviously, was deeply unsettling to the utopian principles that sat at the centre of Fascist ideology. Many of the Italian poliziesco films of the 1970s took their cue from the American cop pictures of that era which featured rogue policemen (Peter Yates’ Bullitt, 1968; William Friedkin’s The French Connection, 1971; Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry, 1972). A notable number of Italian crime films focused on Dirty Harry-style cops (for example, Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta, 1975), but a significant group of others focused on roving groups of banditi – often socially-disenfranchised youth, whose violence was largely motivated by their alienation. The films, such as Romolo Guerrieri’s Liberi, armati, pericolosi (Young, Violent, Dangerous, 1976), don’t always present these banditi sympathetically, but they usually feature an exploration of their milieu and offer reasons why they have turned to violence; it’s easy to see this specific subgroup of films about banditi as Italian society’s attempt to come to terms with the motivations of the, predominantly young, radicals associated with paramilitary groups like the Brigate Rossi (Red Brigades) who committed acts of politically-motivated violence during the 1970s. During the 1960s, the Italian crime film had a short history, but it was one which was closely allied with the concept of socially-minded cinema, with the pictures often being made by filmmakers whose worldview leant strongly towards the political left. In part, this may be because under the Fascist regime during the pre-war period, the production of crime films had been prohibited (or at the very least, frowned severely upon) owing to the perception that they highlighted the fissures within society – something which, obviously, was deeply unsettling to the utopian principles that sat at the centre of Fascist ideology. Many of the Italian poliziesco films of the 1970s took their cue from the American cop pictures of that era which featured rogue policemen (Peter Yates’ Bullitt, 1968; William Friedkin’s The French Connection, 1971; Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry, 1972). A notable number of Italian crime films focused on Dirty Harry-style cops (for example, Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta, 1975), but a significant group of others focused on roving groups of banditi – often socially-disenfranchised youth, whose violence was largely motivated by their alienation. The films, such as Romolo Guerrieri’s Liberi, armati, pericolosi (Young, Violent, Dangerous, 1976), don’t always present these banditi sympathetically, but they usually feature an exploration of their milieu and offer reasons why they have turned to violence; it’s easy to see this specific subgroup of films about banditi as Italian society’s attempt to come to terms with the motivations of the, predominantly young, radicals associated with paramilitary groups like the Brigate Rossi (Red Brigades) who committed acts of politically-motivated violence during the 1970s.

The left-leaning politics of the cine-inchieste are particularly evident in Francesco Rosi’s films, including Salvatore Giuliano, Le mani sulla città (Hands Over the City, 1963) and Il caso Mattei (The Mattei Affair, 1972). These films were often, though not always, based on true stories. Like Rosi’s films and Lizzani’s subsequent Banditi a Milano (The Violent Four, 1968), Svegliati e uccidi has its roots in a true story, reinforcing its connection with the cine-inchieste. Like Rosi’s films too, Lizzani’s Banditi e Milano and Svegliati e uccidi also feature significant roles for Gian Maria Volonte, an actor associated with his outspoken leftist politics. In this film, Volonte plays Inspector Moroni, the Milanese detective who is tasked with apprehending Lutring. (Lizzani’s film, like Liberi, armati, pericolosi, demonstrates an equal focus on the police and banditi: though most of the early sequences of the film depict Lutring’s spiral into a life of increasingly violent banditry, many of the later sequences show an equal focus on Inspector Moroni’s attempts to snare Lutring through appealing to Candida/Yvonne.) The connection with the paradigms of the cine-inchieste is additionally established through Svegliati e uccidi’s elliptical narrative structure – a characteristic of American semidocumentary films noir too – and the way in which it punctuates its narrative with shots of newspaper headlines that underscore Lutring’s progression from petty crook to armed bandit. Aside from reinforcing the semidocumentary approach, the use of this text on the screen also suggests a sensationalistic ‘torn from the headlines’ approach which reminds us of the film’s origins in the true story of Luciano Lutring, the ‘machine gun soloist’.  Roberto Curti has described both Svegliati e uccidi and Banditi a Milano as ‘basically action movies with a strong sociological component, where the minute attention to the sociological prevailed over the spectacular hyperbole’ (Curti, 2013: 7). With these two films, Curti argues, Lizzani essayed ‘an urban crime environment characterized by an individual and consumerist revenge, sometimes hidden under an ostensible social rebellion’ (ibid.). The difference between the two pictures, however, lies in the reasons behind the criminal acts depicted within them: the crimes in Svegliati e uccidi, Curti argues, are dictated by ‘the logic of need’, whereas those depicted within Banditi a Milano are dictated by ‘a logic of profit’ (ibid.: 11). Roberto Curti has described both Svegliati e uccidi and Banditi a Milano as ‘basically action movies with a strong sociological component, where the minute attention to the sociological prevailed over the spectacular hyperbole’ (Curti, 2013: 7). With these two films, Curti argues, Lizzani essayed ‘an urban crime environment characterized by an individual and consumerist revenge, sometimes hidden under an ostensible social rebellion’ (ibid.). The difference between the two pictures, however, lies in the reasons behind the criminal acts depicted within them: the crimes in Svegliati e uccidi, Curti argues, are dictated by ‘the logic of need’, whereas those depicted within Banditi a Milano are dictated by ‘a logic of profit’ (ibid.: 11).

The ‘folk hero’ status of Luciano Lutring, the bandit on whom both this film and José Giovanni’s Le gitan (The Gypsy, 1975, in which the Lutring role is played by Alain Delon), was followed in the 1970s by the notoriety of Milanese thief Renato Vallanzasca, who like Lutring inspired a number of films – such as Sergio Grieco’s La belva col mitra (The Beast with a Gun, 1977) and Michele Placido’s more recent biopic Vallanzasca: Gli angele del male (2010). Svegliati e uccidi takes little from the true story of Lutring, other than his origins as a petty crook in Milan and his movement during the later stages of his criminal career to Paris, where he was eventually captured and imprisoned. Where in Lizzani’s film, Hoffman’s Lutring is incompetent, insecure and prone to outbursts of violence, the real Lutring was reputed to have been an accomplished and successful thief with a strict code of honour who kept his victims calm by telling jokes. If we believe the thief himself, Lutring’s first robbery was committed almost by accident, when he visited a post office for a legitimate reason and the clerk saw a fake gun that Lutring carried, and believing Lutring to be a thief handed him the money from the till. Legend has it that the real Lutring also did his part in the redistribution of wealth, passing stolen money to those less fortunate in a true Robin Hood-style manner. None of this makes its way into Lizzani’s film, which depict Lutring as a somewhat-innocent who is spurred into a never-ending spiral of crime as much by the sensationalistic rhetoric of the press (who, in a quiet news day, put one of Lutring’s crimes front-and-centre in their headlines) as by his own will.  In Lizzani’s film, Lutring meets Yvonne whilst she sings in a nightclub, and throughout much of the rest of the picture Yvonne criticises Lutring’s criminal ways – even attempting to turn him over to the police on a number of occasions – whilst also enjoying the fruits of his ‘labour’. In reality, however, Lutring met his wife Elsa Candida Pasini (nicknamed ‘Yvonne Candy’) when he stole from her at the Italian resort of Cesenatico; Lutring returned Pasini’s cases to her, pretending to have found them, and fell in love with his victim, the demands of whose lifestyle are said to have spurred Lutring on to committing a large number of crimes. In Lizzani’s film, Lutring meets Yvonne whilst she sings in a nightclub, and throughout much of the rest of the picture Yvonne criticises Lutring’s criminal ways – even attempting to turn him over to the police on a number of occasions – whilst also enjoying the fruits of his ‘labour’. In reality, however, Lutring met his wife Elsa Candida Pasini (nicknamed ‘Yvonne Candy’) when he stole from her at the Italian resort of Cesenatico; Lutring returned Pasini’s cases to her, pretending to have found them, and fell in love with his victim, the demands of whose lifestyle are said to have spurred Lutring on to committing a large number of crimes.

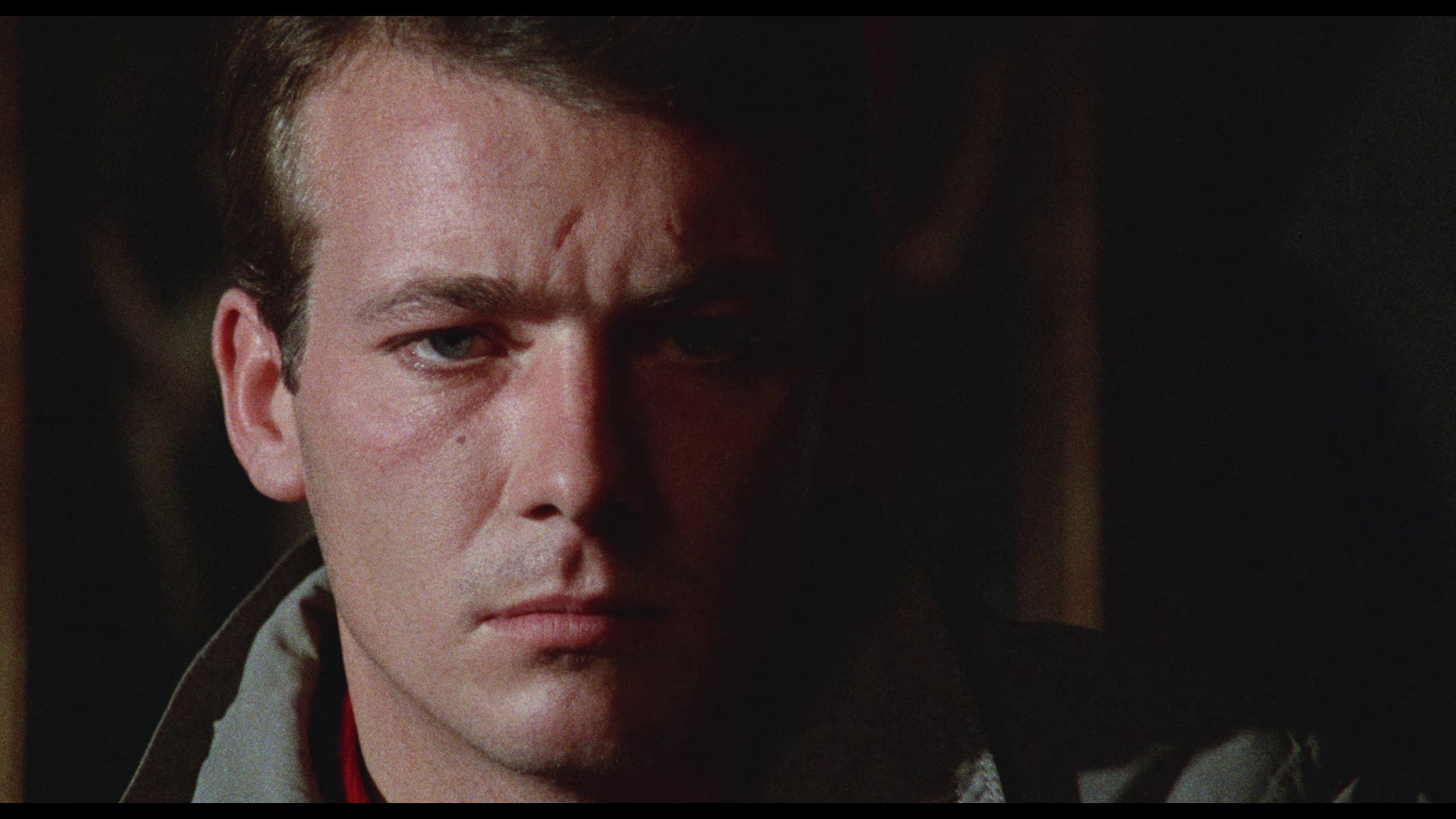

Svegliati e uccidi depicts Lutring as a ‘chancer’ from the outset. The son of a grocer, he is introduced traveling to his father’s shop. Whilst there, he witnesses an act of violence: thugs attack a car and the woman in it, setting fire to the vehicle before firing their machine guns. Others look on in shock and with fear, but Lutring seems energised by what he witnesses. (Much later in the film, a direct parallel between violence and narcotics is drawn when another character, a former partisan, shows Lutring how to use a machine gun, telling the young bandit, ‘Careful, Lutring. Shooting a machine gun is just as bad as cocaine’.) After work, Lutring and some friends visit a nightclub, where Lutring meets Yvonne. Desperate to impress her, Lutring brags about owning a chain of grocer’s shops, telling Yvonne that he plans on opening his own nightclub. Meanwhile, Yvonne too seems desperate to escape her past, telling Lutring that her name is Candida (and that Yvonne is her stage name). This need to impress Yvonne is what forces Lutring to progress from car theft to committing smash-and-grab raids on jewellers’ shops: seizing his opportunity during a parade, Lutring steals an axe from a fire truck and uses it to break the window of a jeweller’s, stealing a number of watches and using them to settle the bill at the hotel where he and Yvonne have been staying.  Meanwhile, Yvonne has big dreams of becoming a top class nightclub singer. Lutring lures her into a relationship by suggesting he is more important than he actually is, and by promising her a job in a nightclub; then, when Yvonne finds herself singing in a club that Lutring believes is beneath her, Lutring drags Yvonne out of the club and complains, ‘I gave up everything a month ago to launch your career, and you let yourself be cheated this way!’ He belittles Yvonne, telling her ‘If you don’t pull out of this shit, if I don’t open a nightclub, you’re a nobody’. Lutring is thus quickly established as a deadbeat and a dreamer, and under his own steam he is unable to achieve anything of note: he is naïve both about life and about crime. Although Yvonne protests as Lutring drags her out of the club, later in the film she mimics his behaviour when she arrives at a nightclub to find that another singer has been hired in her place. Yvonne complains loudly that she has the contract to sing in the club, and threatens the owner with violence: ‘Lutring will get you’, Yvonne shouts, using her husband’s inflated reputation to intimidate the owner, ‘and you’ll go to hell too!’ It seems that despite her protestations against Lutring’s criminal endeavours, Yvonne is willing to remind others of her husband’s reputation as a violent criminal when it suits her. Meanwhile, Yvonne has big dreams of becoming a top class nightclub singer. Lutring lures her into a relationship by suggesting he is more important than he actually is, and by promising her a job in a nightclub; then, when Yvonne finds herself singing in a club that Lutring believes is beneath her, Lutring drags Yvonne out of the club and complains, ‘I gave up everything a month ago to launch your career, and you let yourself be cheated this way!’ He belittles Yvonne, telling her ‘If you don’t pull out of this shit, if I don’t open a nightclub, you’re a nobody’. Lutring is thus quickly established as a deadbeat and a dreamer, and under his own steam he is unable to achieve anything of note: he is naïve both about life and about crime. Although Yvonne protests as Lutring drags her out of the club, later in the film she mimics his behaviour when she arrives at a nightclub to find that another singer has been hired in her place. Yvonne complains loudly that she has the contract to sing in the club, and threatens the owner with violence: ‘Lutring will get you’, Yvonne shouts, using her husband’s inflated reputation to intimidate the owner, ‘and you’ll go to hell too!’ It seems that despite her protestations against Lutring’s criminal endeavours, Yvonne is willing to remind others of her husband’s reputation as a violent criminal when it suits her.

As Yvonne suggests near the start of the film, there is a qualitative difference between Lutring and Yvonne’s former lover Franco: Franco is part of an organised gang, whilst Lutring is an opportunistic bandit. His method evolves (he soon progresses from using an axe to wielding a gun during his robberies) but his cognisance of the milieu of crime is naïve. When the newspaper headlines draw on the news of the discovery of guns at Lutring’s hotel room (labeling Lutring as ‘the sten-gun soloist’), Lutring discovers that life becomes much more expensive: with a fugitive’s reputation, the cost of acquiring a room for the night escalates from 2,000 lire to 50,000 lire. Owing to the press’ need for a sensational headline, Lutring is thus forced further into the criminal world, and Lizzani’s film underscores the ways in which both the media and the police force criminals like Lutring to escalate or evolve in their approach to crime. (Even Lutring seems to acknowledge this, storming into a newspaper’s office and declaring, ‘You journalists made me do too many things. The police are chasing me because of you. And now I have to be armed [….] The police have the weapons’, he concludes, ‘But you [the press] have your fingers on the trigger’.) Lutring approaches a group of criminals with a plan to stage a significant robbery, but as soon as Lutring has left the room, the leader of the group says that Lutring’s idea ‘is a good plan. But we’ll pull it ourselves. The man’s too unstable with the police at his heels. But that makes it more convenient for us. He’ll be the stooge. We’ll let him turn up ten minutes later, and he’ll be caught’. For Lutring, Yvonne is like an item in a jeweller’s window: something he needs to possess. ‘You glitter like a diamond in a shop on Via Montenapoleone’, he tells her during their first meeting at the nightclub. When Yvonne tells Lutring that she has ‘wanted someone like you, with your face and your eyes. But I wanted someone without a criminal record’, Lutring tells her simply that ‘you’re my woman’. Yvonne offers quiet protests to Lutring’s criminal escapades whilst still enjoying the wealth that they bring. When she and Lutring discover that Lutring’s reputation as a criminal has increased the cost of a bed for the night, Yvonne offers to ‘earn that [the cost of a room] with a striptease’. ‘What’s the difference between a striptease and a smash-and-grab?’, Lutring wonders aloud before answering, ‘None. Besides, the husband should provide’. Finally, towards the end of the film Lutring becomes aware that Yvonne has collaborated with Moroni and acts violently towards her, hitting her and threatening her with an axe. ‘I should smash you the way I smash a window’, Lutring tells her before adding pathetically, ‘But I can only kill when I’m scared’. Shortly afterwards, Yvonne speaks with Moroni, telling the detective, ‘He promised me, since we were married…’ ‘His promises aren’t worth anything’, Moroni tells Yvonne, ‘Don’t you see that?’  The film goes to some lengths to establish the difference between gangsterism and banditry: the former is associated with Franco, a member of an established crime family; the latter is associated with Luciano, who finds that owing to his lack of connections he struggles to ‘fence’ the goods he has stolen and is frozen out (or, worse, framed) by other criminal fraternities. (Curiously, in a film which delineates the differences between the ‘gangster’ and the ‘bandit’ so carefully, the subtitles on this release confuse the two terms in at least one pivotal sequence: when in the Italian dialogue Yvonne declares that she doesn’t want to live the rest of her life as a bandit’s wife, the subtitles substitute the word ‘bandit’ for ‘gangster’.) For Inspector Moroni, Lutring is unimportant: though the press have inflated Lutring’s reputation as a bandit, in one sequence Moroni proposes to his men that they let Lutring escape and publicise that escape so as to reel in bigger fish. ‘Lutring’s just a red herring’, Moroni reasons. In Paris, the fence that Lutring approaches, Bobino (Corrado Olmi), tells the young bandit to ‘take my advice and get out of Paris. You’re nothing. Just because the newspapers are writing you up, don’t let your head get big’. Lutring responds by telling Bobino that though he may have in his possession valuable jewels, he is still lacking in what he needs: ‘Bobino, my pockets are full of jewels’, Lutring says, ‘but I’m hungry’. To this, Bobino responds: ‘Jewels in your hand are just nothing, mere stones. You can throw them away if you want to’. The film goes to some lengths to establish the difference between gangsterism and banditry: the former is associated with Franco, a member of an established crime family; the latter is associated with Luciano, who finds that owing to his lack of connections he struggles to ‘fence’ the goods he has stolen and is frozen out (or, worse, framed) by other criminal fraternities. (Curiously, in a film which delineates the differences between the ‘gangster’ and the ‘bandit’ so carefully, the subtitles on this release confuse the two terms in at least one pivotal sequence: when in the Italian dialogue Yvonne declares that she doesn’t want to live the rest of her life as a bandit’s wife, the subtitles substitute the word ‘bandit’ for ‘gangster’.) For Inspector Moroni, Lutring is unimportant: though the press have inflated Lutring’s reputation as a bandit, in one sequence Moroni proposes to his men that they let Lutring escape and publicise that escape so as to reel in bigger fish. ‘Lutring’s just a red herring’, Moroni reasons. In Paris, the fence that Lutring approaches, Bobino (Corrado Olmi), tells the young bandit to ‘take my advice and get out of Paris. You’re nothing. Just because the newspapers are writing you up, don’t let your head get big’. Lutring responds by telling Bobino that though he may have in his possession valuable jewels, he is still lacking in what he needs: ‘Bobino, my pockets are full of jewels’, Lutring says, ‘but I’m hungry’. To this, Bobino responds: ‘Jewels in your hand are just nothing, mere stones. You can throw them away if you want to’.

This release contains both the domestic Italian cut of the film (running 123:51 mins) and the much shorter English-language export cut (running 97:37 mins). The latter is a much more tightly-packed, action-oriented film, cutting out much of the context for Lutring’s behaviour and drawing our focus on Lutring’s criminality. However, it’s arguably a far less interesting version of the film because of that – though the inclusion of both cuts here is something to be thankful for.

Video

The longer Italian version of the film takes up 25Gb of space on the dual layered Blu-ray disc; the shorter English-language version takes up just under 20Gb. Both cuts of the film are presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1; the 1080p presentations utilise the AVC codec. The longer Italian version of the film takes up 25Gb of space on the dual layered Blu-ray disc; the shorter English-language version takes up just under 20Gb. Both cuts of the film are presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1; the 1080p presentations utilise the AVC codec.

The film’s colour 35mm photography is presented very nicely here. The constantly mobile camera – seemingly always panning or tilting – captures the energy and restlessness of youth. The majority of the film, based on a new 2k restoration from the film’s negative, is clear and with a very strong level of detail evident. A very small handful of shots here and there have a softness to them which is a product of the original materials (most likely indicative of damage to the negative) rather than a ‘fault’ of this presentation (see the second of the larger screen grabs that are included at the bottom of this review). Colour reproduction is astounding: there are a couple of nightclub-set scenes, such as the one in which Lutring meets Yvonne for the first time, which feature the image bathed in a vivid crimson light. Very well-balanced contrast levels express the film’s exploration of light and dark nicely. Finally, a superb encode ensures that the film retains the texture and structure of 35mm film. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented, on the Italian version of the film, via a two-channel LPCM track. This display strong depth and range, which is evident throughout the film but mostly noticeable in sequences which feature Ennio Morricone’s superb music for the picture: its Morse code-like piano and percussion, and Lisa Gastoni’s breathy rendition of the song ‘Una stanza vuota’ (distributed as a 7” single at the time of the film’s original release). Audio is presented, on the Italian version of the film, via a two-channel LPCM track. This display strong depth and range, which is evident throughout the film but mostly noticeable in sequences which feature Ennio Morricone’s superb music for the picture: its Morse code-like piano and percussion, and Lisa Gastoni’s breathy rendition of the song ‘Una stanza vuota’ (distributed as a 7” single at the time of the film’s original release).

Optional English subtitles are included for the Italian version of the film. These are accurate, grammatically correct and easy to read but sometimes offer a rather ‘loose’ translation: for example, the confusion of ‘bandito’/‘bandit’ and ‘gangster’ noted above, and in another scene Moroni’s assertion that ‘This is tiring’ is translated as ‘It’s hard’. The English-language export cut of the film is accompanied by a two-channel LPCM track which is clean and clear throughout, and is presented with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The sole extra on the disc, aside from the shorter English-language export cut of the film, is the film’s trailer (1:17). Retail copies of the disc will include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet which contains new writing about the film by Roberto Curti.

Overall

Svegliati e uccidi is an excellent film, especially in its longer Italian cut, which draws focus on the contextual factors which shape Lutring’s transition from petty thief to violent bandit. His ‘progression’ is one that is marked by frustration and the desire for social mobility – but ultimately, Lutring achieves little. He’s positioned as an outsider both by society and the criminal fraternity, and can seek refuge in either – finding that life in the liminal state in which he must live in owing to the reputation given to him by the press, and the constant pursuit by the police, is a space of hunger and need. The film has little relationship with the life of the real Luciano Lutring, and instead takes Lutring’s criminal career as a springboard for a socially-minded narrative about the relationship between the individual and society. As noted above, Svegliati e uccidi sits somewhere between the cine-inchieste and the later poliziesco pictures – like Lizzani’s Banditi a Milano, which is another film, of equal quality to this one, that is desperately in need of a home video release. Svegliati e uccidi is an excellent film, especially in its longer Italian cut, which draws focus on the contextual factors which shape Lutring’s transition from petty thief to violent bandit. His ‘progression’ is one that is marked by frustration and the desire for social mobility – but ultimately, Lutring achieves little. He’s positioned as an outsider both by society and the criminal fraternity, and can seek refuge in either – finding that life in the liminal state in which he must live in owing to the reputation given to him by the press, and the constant pursuit by the police, is a space of hunger and need. The film has little relationship with the life of the real Luciano Lutring, and instead takes Lutring’s criminal career as a springboard for a socially-minded narrative about the relationship between the individual and society. As noted above, Svegliati e uccidi sits somewhere between the cine-inchieste and the later poliziesco pictures – like Lizzani’s Banditi a Milano, which is another film, of equal quality to this one, that is desperately in need of a home video release.

Arrow’s presentation of Svegliati e uccidi is top-notch, and the inclusion of the short English-language export cut is extremely welcome: it offers a very different version of the film, more action-oriented and exciting than the longer Italian version. This release of Svegliati e uccidi is extremely welcome, given the film’s relative rarity on home video formats, and comes with a very strong recommendation.    References: Curti, Roberto, 2013: Italian Crime Filmography: 1968-1980. London: McFarland

|

|||||

|