|

|

Reflecting Skin (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Soda Pictures Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th December 2015). |

|

The Film

The Reflecting Skin (Philip Ridley, 1990) The Reflecting Skin (Philip Ridley, 1990)

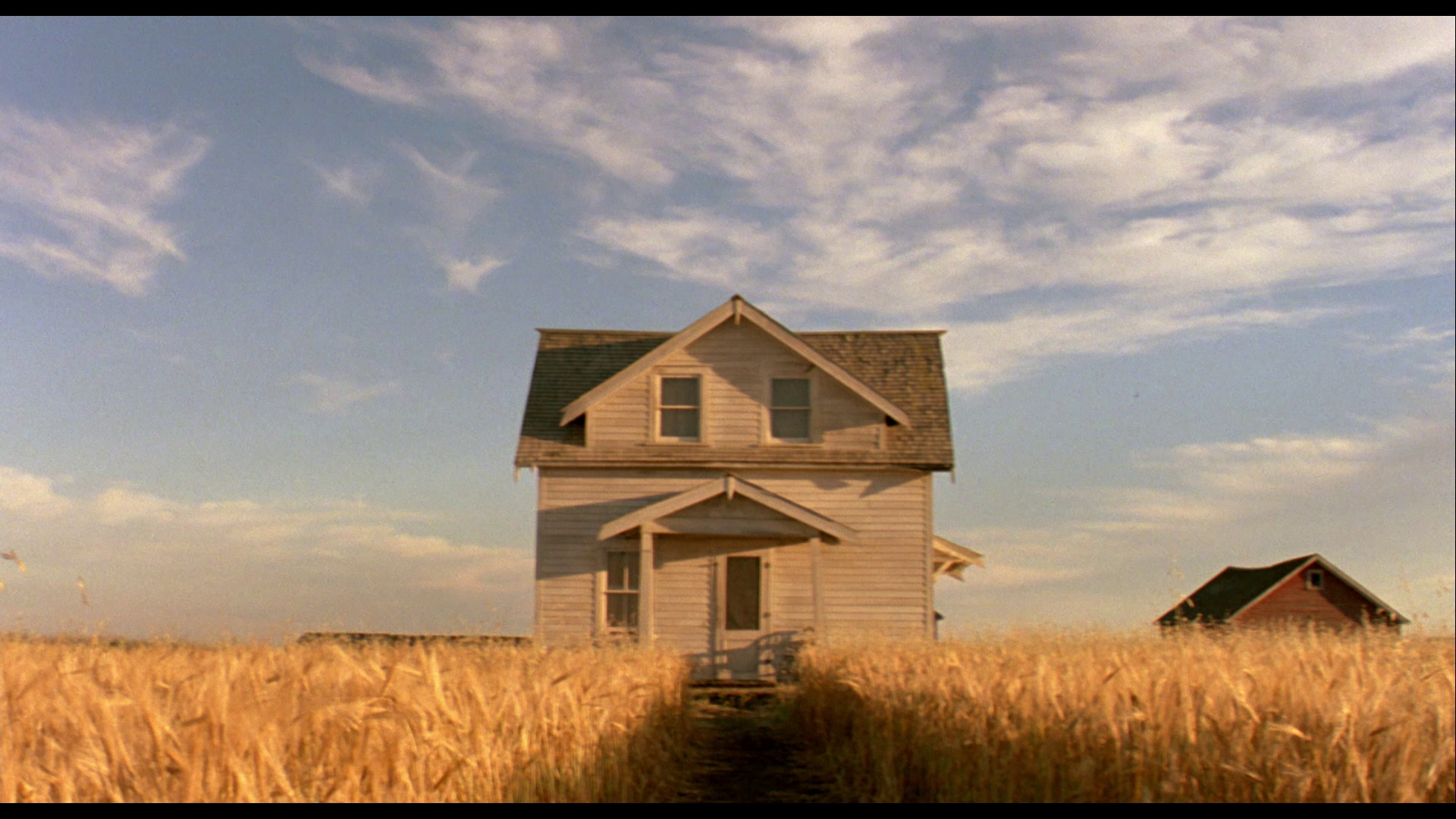

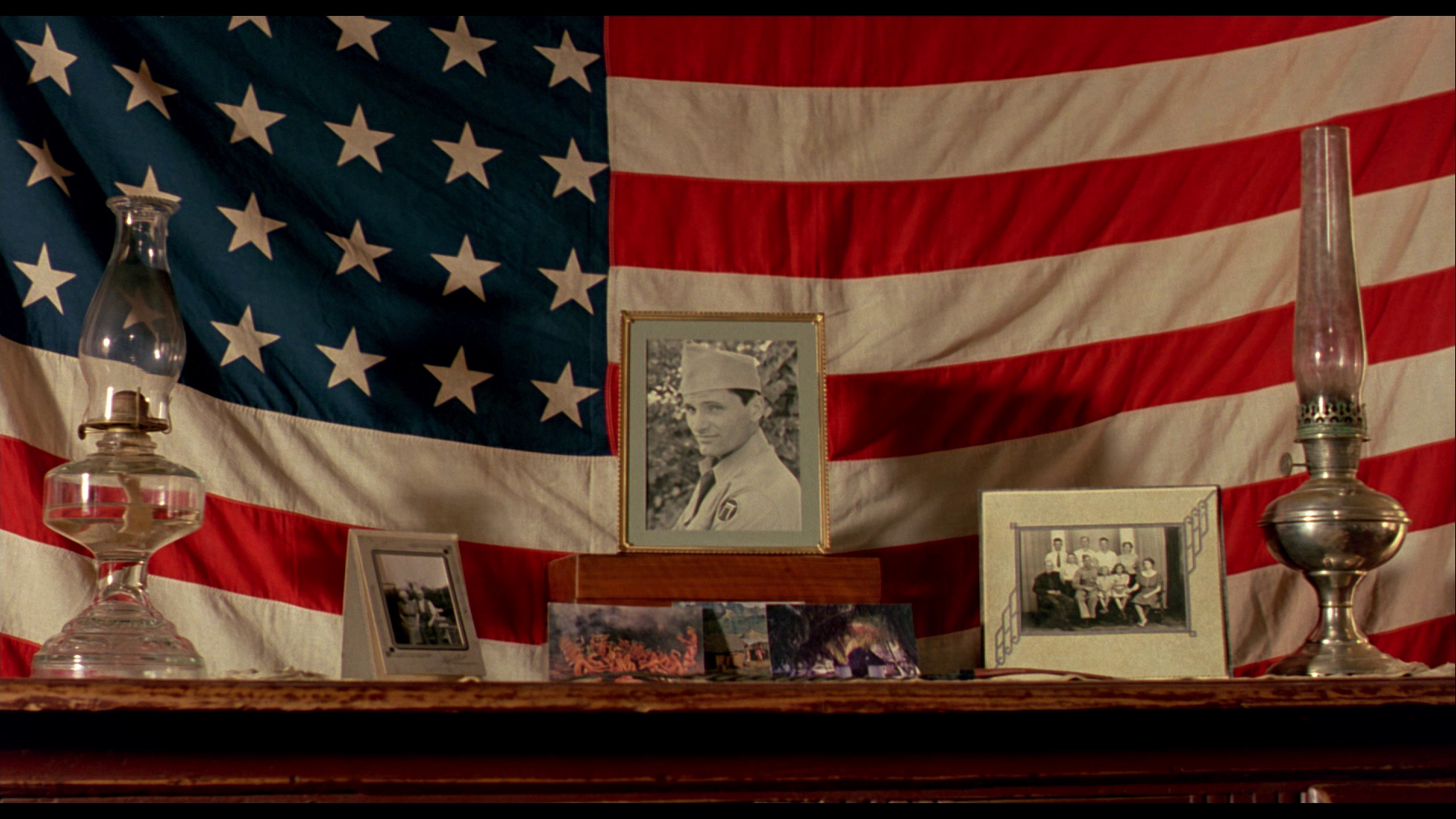

Philip Ridley’s feature debut as a director, The Reflecting Skin (1990) followed Ridley’s success as an artist and novelist, and his work as a screenwriter, writing the script for Peter Medak’s The Krays (1990). The film takes place in a small Midwestern American community during the 1950s. There, eight year old Seth Dove (Jeremy Cooper) lives a harsh life with his overbearing, overcritical mother Ruth (Sheila Moore) and his father Luke (Duncan Fraser); the latter is an insecure, introverted man - a social pariah owing to the fact that he was once caught in an embrace with another man. Nevertheless, Luke exhibits a kindness towards Seth that is lacking in the boy’s mother; for her part, Ruth eagerly awaits the return of her eldest son Cameron (Viggo Mortensen), who has been stationed with the navy in the Pacific during the nuclear bomb tests. After having a discussion about vampires with his pulp novel-loving father, Seth becomes convinced that the eccentric widow who lives nearby, Dolphin Blue (Lindsay Duncan), is herself a vampire. Meanwhile, the arrival of three young men in a shiny black care presages the murder of Seth’s friend Eben (Codie Lucas Wilbee). Sheriff Ticker (Robert Koons) claims that Luke must have had something to do with Eben’s murder, owing to Luke’s homosexual past. However, Seth believes Dolphin to have killed his friend. Beset with the suspicions of the community, Luke commits suicide, setting himself on fire in front of his young son. This doesn’t prevent Seth’s other friend Kim (Evan Hall) from being abducted and murdered by the young men in the car. Meanwhile, Cameron returns home and, at Luke’s graveside, begins a romantic relationship with Dolphin Blue, much to the consternation of young Seth.  Viggo Mortensen, who acted both in The Reflecting Skin and Philip Ridley’s second feature The Passion of Darkly Noon (1995), has noted that in Ridley’s films ‘[t]here is an element there, that kind of scary thing going on in his movies and he does it for very little money[, achieving] the look that a lot of directors can only wish that they could get with much bigger budgets’ (Mortensen, quoted in Carnell, 2015: np). The film has a very strong sense of place, conjured up through the barest of settings: sweeping wheatfields, a small graveyard, a barn and a small handful of strange, isolated farmhouses. Wolf Forrest has noted that ‘the location is Idaho and the film Canadian, [but the picture] has the look of the rural Midwest’ (Forrest, 2013: 30). It’s a Midwest that’s a deceptively dangerous place, the same American Midwest that’s depicted in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and, as Forrest highlights, in much of the fiction of Ray Bradbury (ibid.). ‘The essence of Midwest horror’, Forrest argues, ‘comes from the horror of flatness’ (ibid.). Viggo Mortensen, who acted both in The Reflecting Skin and Philip Ridley’s second feature The Passion of Darkly Noon (1995), has noted that in Ridley’s films ‘[t]here is an element there, that kind of scary thing going on in his movies and he does it for very little money[, achieving] the look that a lot of directors can only wish that they could get with much bigger budgets’ (Mortensen, quoted in Carnell, 2015: np). The film has a very strong sense of place, conjured up through the barest of settings: sweeping wheatfields, a small graveyard, a barn and a small handful of strange, isolated farmhouses. Wolf Forrest has noted that ‘the location is Idaho and the film Canadian, [but the picture] has the look of the rural Midwest’ (Forrest, 2013: 30). It’s a Midwest that’s a deceptively dangerous place, the same American Midwest that’s depicted in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and, as Forrest highlights, in much of the fiction of Ray Bradbury (ibid.). ‘The essence of Midwest horror’, Forrest argues, ‘comes from the horror of flatness’ (ibid.).

Ridley has highlighted the film’s use of two dominant colours: yellow, represented through the wheatfields; and blue (Ridley, 1997: np). The bold yellow of the wheat – not its actual colour, which is closer to a ‘dirty brown’ – was achieved by the use of coral filters on the lenses, and by Ridley actually painting the wheat in some sequences, such as the scene in which Seth approaches Dolphin’s house near the film’s opening (ibid.). This effect was emphasised by shooting taking place only during the late afternoon and ‘magic hour’ so that Ridley could depict ‘the sun […] at its most intense and golden’, accompanied by long, deep shadows (ibid.). During production, the cast and crew would rehearse in the morning and shoot the scenes between four and eight in the afternoon (ibid.).  Against this dominance of blue and yellow, Ridley had the actors dressed in monochromatic costumes, and dyed Viggo Mortensen and Jeremy Cooper’s hair black. The opening sequence features this juxtaposition between the vibrant wheat, the blue sky and the monochromatic appearance of the film’s characters: it features Seth crossing the wheatfield, entering from the right of the frame and, framed in a long shot, looking very small. He is carrying a frog and meets with his friends Eben and Kim. ‘Look at this wonderful frog’, Seth declares. The young friends gather round and use a reed to inflate the frog. They leave it by the roadside and hide in the grass as Dolphin approaches. She stoops to look at the bloated frog, and from their hiding place the boys use a catapult to ‘pop’ the creature. Blood splashes over Dolphin’s face, and she screams. Against this dominance of blue and yellow, Ridley had the actors dressed in monochromatic costumes, and dyed Viggo Mortensen and Jeremy Cooper’s hair black. The opening sequence features this juxtaposition between the vibrant wheat, the blue sky and the monochromatic appearance of the film’s characters: it features Seth crossing the wheatfield, entering from the right of the frame and, framed in a long shot, looking very small. He is carrying a frog and meets with his friends Eben and Kim. ‘Look at this wonderful frog’, Seth declares. The young friends gather round and use a reed to inflate the frog. They leave it by the roadside and hide in the grass as Dolphin approaches. She stoops to look at the bloated frog, and from their hiding place the boys use a catapult to ‘pop’ the creature. Blood splashes over Dolphin’s face, and she screams.

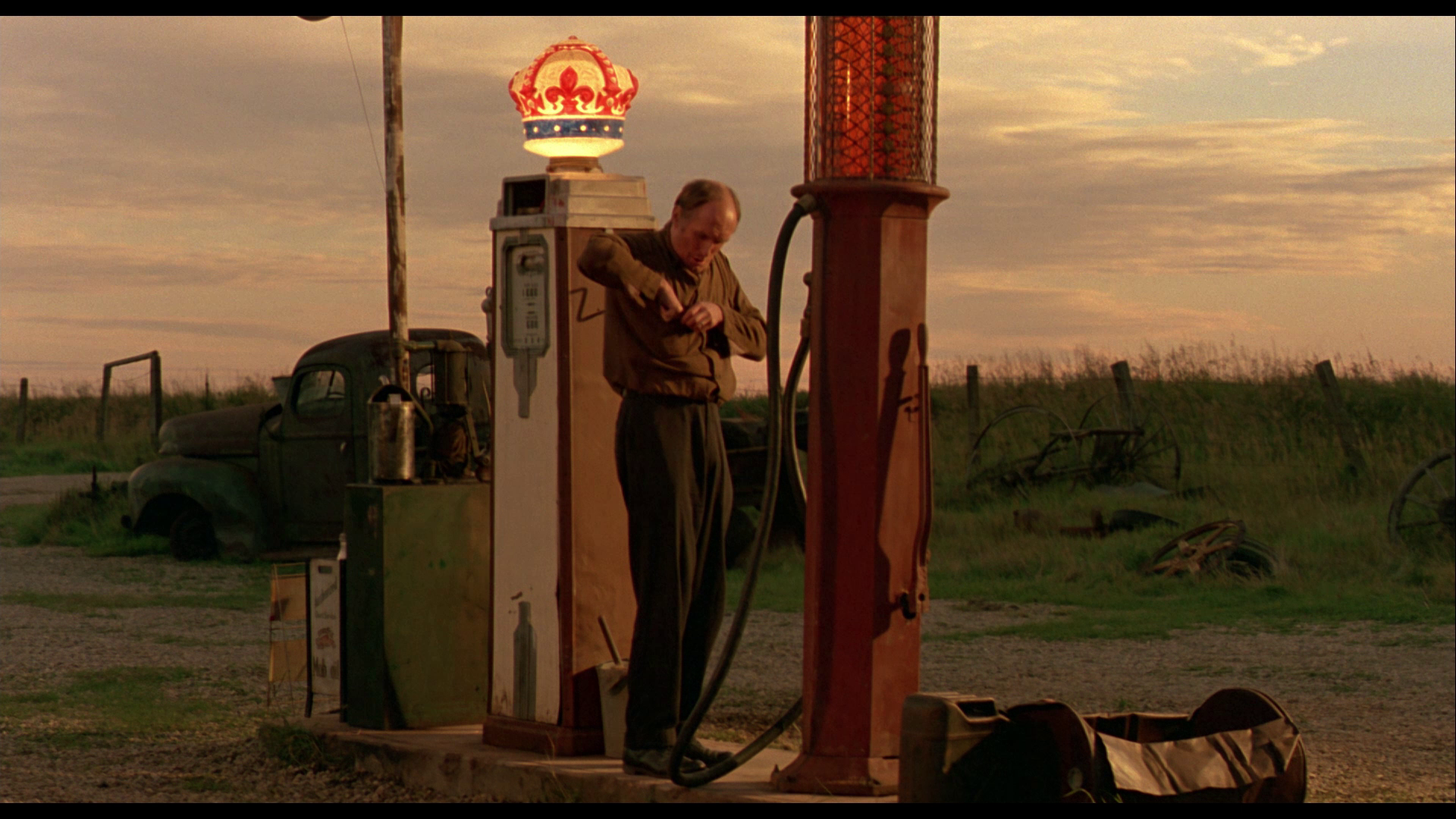

From here, the boys flee and hide in a barn. There, they reflect on death and morality, offering a naďve interpretation of both. ‘Ma says it’s wrong […] exploding frogs [….] She says it’s a sin to kill things’, Kim says, adding, ‘My ma’s dead. She’s in heaven’. ‘No, she’s not. She’s in a coffin’, Eben corrects him. ‘Not true. She’s in heaven. She’s an angel’, Kim protests. ‘What’s an angel?’, Seth asks. ‘A baby with wings, Every time you make ma cry, you kill an angel’, Eben informs him. ‘Someone who doesn’t blink’, Kim says, ‘They go to heaven and be an angel’. ‘Not true, Eben’, Eben says, ‘Your ma’s in a coffin being eaten by worms’. Later, after Eben has been abducted and his body discovered, Seth and Kim discover in the barn a mummified foetus. He becomes convinced that the foetus is Eben, returned to Earth in the form of an angel: ‘Murdered angels don’t go to heaven. They get their wings tore off and thrown back to Earth again’, he reasons to Kim. Seth sneaks the foetus into his home and hides it in his room, conversing with it at nighttime and telling it his fears (that Dolphin will ‘suck his [Cameron’s] blood and kill him’ – like Seth believes she killed Eben).  The film’s depiction of childhood offers stark contrast to the ways in which childhood is usually depicted within popular cinema. Reflecting on Jeremy Cooper’s performance as Seth, Ridley has commented that the fact that Cooper doesn’t act in the way one usually associated with cinematic depictions of children is ‘what people found so disturbing. It’s not an adult’s idea of childhood. It’s what childhood is really like. People have said to me, “Oh, Seth is such a wicked, evil little boy.” And I always reply, “No, he’s not. He’s just normal.” In many ways, you know, he is the only normal thing in the film’ (ibid.; emphasis in original). The casual cruelty of Seth and his friend’s treatment of the frog, it seems, is not an isolated occurrence: when Seth is sent by his parents to apologise to Dolphin Blue, she tells him ‘We used to tie fireworks to cats’ tails and set them on fire? Ever do that?’ Seth looks on silently, shocked. ‘Oh, you should do that’, Dolphin tells him before also talking of putting a canary in an oven. For their part, Seth’s parents – especially his mother – do their best to dispel notions of childhood as an ideal state. In one sequence, Ruth cruelly punishes her young son by forcing him to drink water ‘until your stomach’s fit to burst’. Meanwhile, accused of the murder of Eben by Sheriff Ticker (whose deputy, commenting in reference to Luke’s previous arrest for being caught ‘in full embrace’ with a seventeen year old young man, suggests ‘Sheriff Ticker says it’s a short leap from kissing to killing), Luke drinks petrol from the garage pump and, pouring it over himself, sets himself alight in front of Seth. The film’s depiction of childhood offers stark contrast to the ways in which childhood is usually depicted within popular cinema. Reflecting on Jeremy Cooper’s performance as Seth, Ridley has commented that the fact that Cooper doesn’t act in the way one usually associated with cinematic depictions of children is ‘what people found so disturbing. It’s not an adult’s idea of childhood. It’s what childhood is really like. People have said to me, “Oh, Seth is such a wicked, evil little boy.” And I always reply, “No, he’s not. He’s just normal.” In many ways, you know, he is the only normal thing in the film’ (ibid.; emphasis in original). The casual cruelty of Seth and his friend’s treatment of the frog, it seems, is not an isolated occurrence: when Seth is sent by his parents to apologise to Dolphin Blue, she tells him ‘We used to tie fireworks to cats’ tails and set them on fire? Ever do that?’ Seth looks on silently, shocked. ‘Oh, you should do that’, Dolphin tells him before also talking of putting a canary in an oven. For their part, Seth’s parents – especially his mother – do their best to dispel notions of childhood as an ideal state. In one sequence, Ruth cruelly punishes her young son by forcing him to drink water ‘until your stomach’s fit to burst’. Meanwhile, accused of the murder of Eben by Sheriff Ticker (whose deputy, commenting in reference to Luke’s previous arrest for being caught ‘in full embrace’ with a seventeen year old young man, suggests ‘Sheriff Ticker says it’s a short leap from kissing to killing), Luke drinks petrol from the garage pump and, pouring it over himself, sets himself alight in front of Seth.

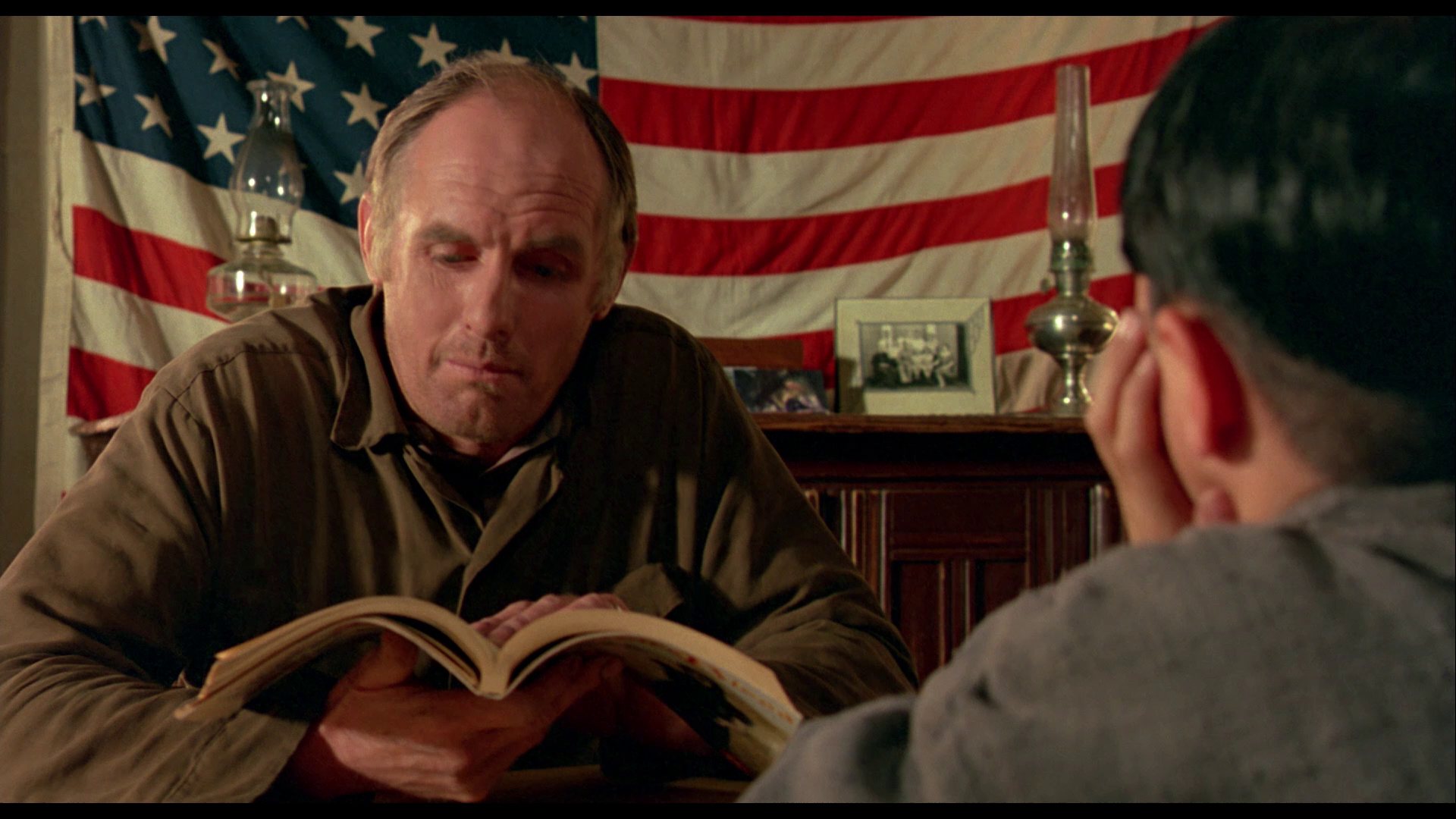

The film’s chief symbol of authority, Sheriff Ticker, seems equally ill at ease in communicating with a child, asking Seth (after Luke’s death), ‘Your pa, he ever touch you?’ ‘Yeah’, Seth replies matter-of-factly. ‘Where’d he touch you, boy?’, Ticker asks. ‘In the kitchen’, Seth tells him. ‘Did he ever touch you in other places?’, Ticker asks. ‘Places outside the kitchen?’, Seth queries. ‘No, er, places on your person? [….] Like private places, boy?’, Ticker asks, grabbing Seth’s crotch (offscreen), ‘Like here, boy?’ ‘No, he didn’t do much touching’, Seth responds. Later, at the end of the film, Dolphin tells Seth about life: ‘Poor Seth’, she says, ‘It’s all so horrible, isn’t it? The nightmare of childhood. And it only gets worse. One day you’ll wake up, and you’ll be past it. Your beautiful skin will wrinkle a shrivel up. You’ll lose your hair, your sight, your memory. Your blood will thicken, teeth turn yellow and loose. You’ll start to stink and fart, and all your friends will be dead. You’ll succumb to arthritis, angina, senile dementia. You’ll piss yourself, shit yourself, drool at the mouth. Just pray that when this happens, you’ve got someone to love you. Because if you’re loved you’ll still be young. Oh, innocence can be hell’.  Seth’s confusion about the world is compounded when he asks Luke about the book that he is reading – a pulp novel about vampires. ‘What’s vampires?’, Seth asks. ‘They’re not very nice’, Luke says in a deadpan manner, ‘They bite your neck and drink your blood. Stuff like that. Not very sociable’. ‘What’d they do that for, Pa?’, Seth asks. ‘Because if they don’t, they get old. They do it to stay young’, Luke says, ‘And the people whose blood they drink, why, they get old and then they die’. ‘Any vampires around these parts, Pa?’, Seth asks. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised’, Luke tells his son. Seth looks around and sees Dolphin; he connects Dolphin’s eccentric behaviour with what his father has told him about vampires. Almost immediately after, he encounters the film’s real villains: the three young men in the shiny black car, who murder first Eben and, later, Kim – deaths that Seth attributes to Dolphin, and that Sheriff Ticker attributes to Luke. Seth’s confusion about the world is compounded when he asks Luke about the book that he is reading – a pulp novel about vampires. ‘What’s vampires?’, Seth asks. ‘They’re not very nice’, Luke says in a deadpan manner, ‘They bite your neck and drink your blood. Stuff like that. Not very sociable’. ‘What’d they do that for, Pa?’, Seth asks. ‘Because if they don’t, they get old. They do it to stay young’, Luke says, ‘And the people whose blood they drink, why, they get old and then they die’. ‘Any vampires around these parts, Pa?’, Seth asks. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised’, Luke tells his son. Seth looks around and sees Dolphin; he connects Dolphin’s eccentric behaviour with what his father has told him about vampires. Almost immediately after, he encounters the film’s real villains: the three young men in the shiny black car, who murder first Eben and, later, Kim – deaths that Seth attributes to Dolphin, and that Sheriff Ticker attributes to Luke.

In the aforementioned scene in which Seth is sent to apologise to Dolphin, she greets him at the door with the phrase, ‘Come in. I won’t bite’. Seth, already suspecting that Dolphin may be a vampire like those depicted within his father’s book, is visibly terrified by this greeting. Dolphin tells Seth of her husband, Adam, who was a whaler who became a farmer. She tells Seth graphically about Adam’s suicide. ‘Sometimes terrible things happen quite naturally’, she suggests in a line which seems to summarise the film’s narrative as a whole. ‘You look different’, Seth says, commenting on Dolphin’s appearance in the photographs she shows him. ‘He made me younger, I suppose [….] Without him, I get older. Bits of me fall off’, Dolphin tells him before adding – jokingly – that she is in reality two hundred years old and cannot bear to look in a mirror. A typical child, Seth takes Dolphin’s comments literally and looks increasingly disturbed as what Dolphin says seems to confirm his belief that she is indeed a vampire. That night, Seth reads his father’s book, Vampire Blood, and inspired by the novel attempts to protect himself by fashioning a makeshift crucifix out of some wood. Focalised through Seth, and offering a childlike perspective of the society in which he lives, the film offers a bleak depiction of the world. Characters espouse defeatist philosophies, showing a tendency to present them to Seth, who offers a blank canvas that reflects these ideas back upon the adults speaking to him. During their meeting in her home, Dolphin reflects on love to Seth, telling him ‘You fall in love, and almost at once that loved one dies and you’re left with nothing. Nothing at all. Just a few memories and a house where he was a boy. Nothing but dreams and decay’. Cameron’s return home is anticipated by both Ruth and Seth, who idealises his older brother. Cameron carries with him a photograph of him and Seth together, the young boy on his older brother’s shoulders. However, Cameron is a dour man, apparently scarred by what he witnessed in the Pacific. Reflecting on their now-deceased father, Luke, Cameron observes that ‘He was always reading. Nothing but them cheap pulps. Never said a word to me as a kid. Just sat there and got old’. Talking to Luke’s grave, Cameron asserts, ‘You never stood a chance. Should have got out years ago, before she drained you’.  When Cameron meets and begins a relationship with Dolphin, however, he has less and less time for the younger brother who idealises him so. As Cameron and Dolphin converse at the small graveyard – Cameron is there to visit Luke’s grave, and Dolphin is present to visit the grave of her dead husband – Seth tries to warn his brother about Dolphin’s status as a ‘vampire’. Cameron becomes increasingly ill-tempered, eventually yelling at Seth to ‘Beat it’ before muttering to the child, ‘I’m gonna kill you’, and pushing him to the floor. When Cameron meets and begins a relationship with Dolphin, however, he has less and less time for the younger brother who idealises him so. As Cameron and Dolphin converse at the small graveyard – Cameron is there to visit Luke’s grave, and Dolphin is present to visit the grave of her dead husband – Seth tries to warn his brother about Dolphin’s status as a ‘vampire’. Cameron becomes increasingly ill-tempered, eventually yelling at Seth to ‘Beat it’ before muttering to the child, ‘I’m gonna kill you’, and pushing him to the floor.

In Ruth’s rhetoric, the exotic locations in which Cameron has witnessed the testing of nuclear bombs – presumably the Marshall Islands – is juxtaposed with the smalltown lives of her and her family. Ignoring the destruction incurred by the nuclear tests in the Pacific, Ruth idealises the islands on which Cameron is, or has been, stationed: she declares ‘There’s coconuts on the pretty islands. Not a car in sight. Not like this dump’, before promising ‘Things’ll be different when Cameron gets back. Things’ll change’. When Cameron returns, he shows Seth a photograph which offers an index of his time in the Pacific and his association with the nuclear tests: it’s a monochrome photograph of a baby in Japan whose ‘skin got all silver and shiny so you could see your face in it’. (It’s one of three photographs that Cameron carries in his wallet: the other two are a generic nudie-cutie and the photograph of Cameron and Seth, Seth on Cameron’s shoulders.) As Cameron begins a relationship with Dolphin, Seth sneaks into Dolphin’s house and spies on his brother’s conversation with the widow. Cameron tells Dolphin about witnessing the nuclear tests in the Pacific: ‘The natives would paddle out in their canoes, singing’, Cameron says, ‘And there’d be this stuff like silver snow falling on the ship. We’d roll it up and have snowball fights with it, you know? And after each blast, the sea would be filled with […] boiled fish’. As Cameron becomes increasingly involved with Dolphin, Seth begins to notice changes in his brother: Cameron’s gums are bleeding, he’s losing weight and his hair is thinning. Seth ascribes these symptoms (most likely the product of Cameron’s prolonged exposure to radiation) to Dolphin’s status as a ‘vampire’: ‘That is why you’re getting older and she’s getting younger’, Seth says. This leads to a dramatic confrontation between Seth and Cameron, which results in Cameron cruelly calling Seth a ‘little bastard’ and telling the child to ‘shut up’. ‘Why don’t you go play with your friends?’, Cameron asks at the end of the film. To this, Seth replies, ‘They’re all dead’; the film ends on the image of the utterly lonely Seth running into one of the wheatfields, screaming in despair, whilst – shot in silhouette – his little hands reach up towards the sky. The Reflecting Skin is here presented uncut, with a running time of 95:53 mins.

Video

The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Approved by Philip Ridley himself, the new restoration used for this presentation was apparently based on a 2k scan of the film’s interpositive, so the contrast levels here are a little ‘punchier’ than what might be expected from a restoration sourced from the negative. Nevertheless, there’s a subtle gradation from light to dark, which can be seen in the sequence in which Seth and his friends hide out in the barn, a shaft of subtly diffused light illuminating the centre of the composition and the edges tapering off into darkness. The colours are vivid, capturing the juxtaposition of blue and golden yellows beautifully – and offsetting these with the monochromatic costumes of the principle characters. (This can be seen in the opening shot, which features a wheatfield into which Seth, clad in black and white, enters, diminished within his surroundings and seeming to be swallowed up by the golden hues of the wheat.) There’s an excellent level of detail throughout, though here and there some softness is apparent which may suggest the application of some digital noise reduction software somewhere along the line, or may simply be inherent within the source material. The restoration is free from debris and damage and, thanks to a strong encode, retains much of the structure of 35mm film. It’s a very pleasing presentation, certainly the best home video presentation that the film has seen so far. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Approved by Philip Ridley himself, the new restoration used for this presentation was apparently based on a 2k scan of the film’s interpositive, so the contrast levels here are a little ‘punchier’ than what might be expected from a restoration sourced from the negative. Nevertheless, there’s a subtle gradation from light to dark, which can be seen in the sequence in which Seth and his friends hide out in the barn, a shaft of subtly diffused light illuminating the centre of the composition and the edges tapering off into darkness. The colours are vivid, capturing the juxtaposition of blue and golden yellows beautifully – and offsetting these with the monochromatic costumes of the principle characters. (This can be seen in the opening shot, which features a wheatfield into which Seth, clad in black and white, enters, diminished within his surroundings and seeming to be swallowed up by the golden hues of the wheat.) There’s an excellent level of detail throughout, though here and there some softness is apparent which may suggest the application of some digital noise reduction software somewhere along the line, or may simply be inherent within the source material. The restoration is free from debris and damage and, thanks to a strong encode, retains much of the structure of 35mm film. It’s a very pleasing presentation, certainly the best home video presentation that the film has seen so far.

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is clean and clear, rich and resonant. It’s accompanied by optional English subtitles.

Extras

Extras on the disc include:  - an isolated score, presented in LPCM 2.0 stereo. - an isolated score, presented in LPCM 2.0 stereo.

- an audio commentary with director Philip Ridley. Ridley talks in detail about the production of the film, reflecting on its aesthetic and the sets and locations used within the picture. He discusses the photography and the film’s use of colour, the symbolism within the picture and the casting, and he engages with the ways in which the film developed from the original script. It’s an engaging commentary track, packed with information. - a new documentary: ‘Angels and Atom Bombs: The Making of The Reflecting Skin’ (43:41). This is a fascinating account of the making of the picture, told via a series of new interviews with Ridley, Mortensen, cinematographer Dick Pope and the film’s composer Nick Bicât. There’s some overlap with Ridley’s commentary track, which is to be expected, but Ridley also offers some new information. The interviews with the other participants are equally illuminating, particularly the interview with Dick Pope, who discusses some of the specific influences upon the film’s photography. - a new featurette: ‘Dreaming Darkly’ (16:14). Interviewed separately, Ridley, Mortensen and Bicât reflect on the next feature that Ridley would direct, The Passion of Darkly Noon. - two short films by Ridley: -- ‘Visiting Mr Beak’ (1987; 21:08). This strange, unsettling short film focuses on a young boy who is interrupted on his way to deliver a mysterious item to the titular Mr Beak. Its focus on childhood links it with Ridley’s debut feature. ‘Visiting Mr Beak’ was shot in 35mm but is here presented via a VHS-sourced copy owing to the absence of the original film materials. This short film has an optional introduction by Ridley (3:29). -- ‘The Universe of Dermot Finn’ (1988; 11:16). Made for Channel 4, this short film was named Best Short Film at Cannes. It focuses on Dermot Finn, who visits the family of his lady love Pearl, and is surprised to find himself seated at a table in a giant bird’s nest, where he is fed raw fish. This too has an optional introduction by Ridley (2:01). - a gallery of poster and video art (1:51). - a stills gallery (7:36). - two trailers: the film’s theatrical trailer (2:24), and its re-release trailer (2:26). - a number of bonus trailers for Soda Pictures’ other releases.

Overall

The Reflecting Skin is a combative, often darkly comic – and sometimes simply dark – picture. During the film’s premiere at Cannes, there was, in Ridley’s words, a ‘mass exodus’ of audience members during the scene in which ‘the frog explodes over Lindsay Duncan’ (ibid.). However, the film received rave reviews and rapidly acquired a cult following. Certainly, it’s notable for its haunting depiction of childhood: the adults within the film fail to act sympathetically towards the children or to ensure their safety, and the world within the picture is characterised by cruelty, neglect, scorn, ridicule and derision. I remember finding the picture disturbing when I first viewed it in the early 1990s; it’s even more unsettling now that I am a parent, and the final moments in particular (Seth’s desperate cries in the middle of the lonely field, his child’s hands reaching up to the sky in a plea for deliverance) are absolutely heartbreaking. Of course, that’s not to sidestep the film’s delicious moments of black comedy. It’s an impressive film, perhaps not for all tastes, but rewarding to a patient viewer. The Reflecting Skin is a combative, often darkly comic – and sometimes simply dark – picture. During the film’s premiere at Cannes, there was, in Ridley’s words, a ‘mass exodus’ of audience members during the scene in which ‘the frog explodes over Lindsay Duncan’ (ibid.). However, the film received rave reviews and rapidly acquired a cult following. Certainly, it’s notable for its haunting depiction of childhood: the adults within the film fail to act sympathetically towards the children or to ensure their safety, and the world within the picture is characterised by cruelty, neglect, scorn, ridicule and derision. I remember finding the picture disturbing when I first viewed it in the early 1990s; it’s even more unsettling now that I am a parent, and the final moments in particular (Seth’s desperate cries in the middle of the lonely field, his child’s hands reaching up to the sky in a plea for deliverance) are absolutely heartbreaking. Of course, that’s not to sidestep the film’s delicious moments of black comedy. It’s an impressive film, perhaps not for all tastes, but rewarding to a patient viewer.

Soda Pictures’ presentation of the film is very good, a significant improvement over the film’s previous home video releases – including the Blu-ray released in Germany by Starlight. The solid presentation of the main feature is accompanied by some absolutely superb contextual material, making this release a highly recommended purchase. References: Carnell, Thom, 2015: The Carpe Noctem Interviews, Vol. 2. Crossroad Press Forrest, Wolf, 2013: ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentices: How the Lives of Three Regional “Weird Fiction” Writers Became Creatively Entangled’. In: McMillan, Gloria (ed), 2013: Orbiting Ray Bradbury’s Mars. London: McFarland and Company: 24-38 Ridley, Philip, 1997: The American Dreams: ‘The Reflecting Skin’ and ‘The Passion of Darkly Noon’ – Two Screenplays by Philip Ridley. London: Bloomsbury

|

|||||

|