|

|

Mr. Majestyk (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th January 2016). |

|

The Film

Mr Majestyk (Richard Fleischer, 1974) Mr Majestyk (Richard Fleischer, 1974)

Originally intended as a vehicle for Clint Eastwood, following writer Elmore Leonard’s earlier collaboration with Eastwood on John Sturges’ Western Joe Kidd (1972), Mr Majestyk (Richard Fleischer, 1974) was written by Leonard; reversing the usual book-to-film process, Leonard adapted his script into a novella, published the in the same year as the film’s release, which reads more like an extended film treatment in the manner of Graham Greene’s The Third Man (published in 1950). After writing the script for Mr Majestyk, Elmore Leonard retired from writing screenplays, claiming in interview that this was ‘Because I don’t like writing screenplays. And I have never worked with a real good director. If I had, I would probably still write one once in a while’ (Leonard, quoted in LoCicero, 2014: np). As noted above, the project was originally intended as a vehicle for Clint Eastwood, and Leonard reputedly wrote the screenplay after Eastwood telephoned Leonard one night and asked the writer to ‘write me another Dirty Harry, only different’ (Leonard, quoted in Challen, 2000: 78; quoting Clint Eastwood). Leonard reflected on this proposition overnight, ‘and I called him up the next day in Carmel, and I told him the story of Mr Majestyk’ (Leonard, quoted in ibid.). However, Eastwood became involved in making High Plains Drifter (1973) and Mr Majestyk was passed on to Walter Mirisch, who after considering Steve McQueen hired Charles Bronson to act in the picture (D’Ambrosio, 2012: 148).  Taking place in Colorado, Mr Majestyk begins with Vincent Majestyk (Bronson) in a small town, rounding up labourers for his 160 acre watermelon farm. It’s Majestyk’s second crop, and he needs to ensure that it’s successful in order to stay afloat financially. In town, he meets and hires Nancy Chavez (Linda Cristal), a union worker, when he defends her from the prejudice of an employee at the local gas station. Returning to his farm with Nancy and the other labourers, Majestyk is met by Bobby Kopas (Paul Koslo). Kopas already has a crew working in Majestyk’s fields; it’s a racket, of course, and Kopas is trying to railroad Majestyk into employing the men he’s found – mostly drunks – and paying Kopas a finder’s fee. Majestyk refuses; Kopas pulls out a shotgun and holds it to Majestyk. Majestyk quickly takes the gun from Kopas and runs him off the farm. Taking place in Colorado, Mr Majestyk begins with Vincent Majestyk (Bronson) in a small town, rounding up labourers for his 160 acre watermelon farm. It’s Majestyk’s second crop, and he needs to ensure that it’s successful in order to stay afloat financially. In town, he meets and hires Nancy Chavez (Linda Cristal), a union worker, when he defends her from the prejudice of an employee at the local gas station. Returning to his farm with Nancy and the other labourers, Majestyk is met by Bobby Kopas (Paul Koslo). Kopas already has a crew working in Majestyk’s fields; it’s a racket, of course, and Kopas is trying to railroad Majestyk into employing the men he’s found – mostly drunks – and paying Kopas a finder’s fee. Majestyk refuses; Kopas pulls out a shotgun and holds it to Majestyk. Majestyk quickly takes the gun from Kopas and runs him off the farm.

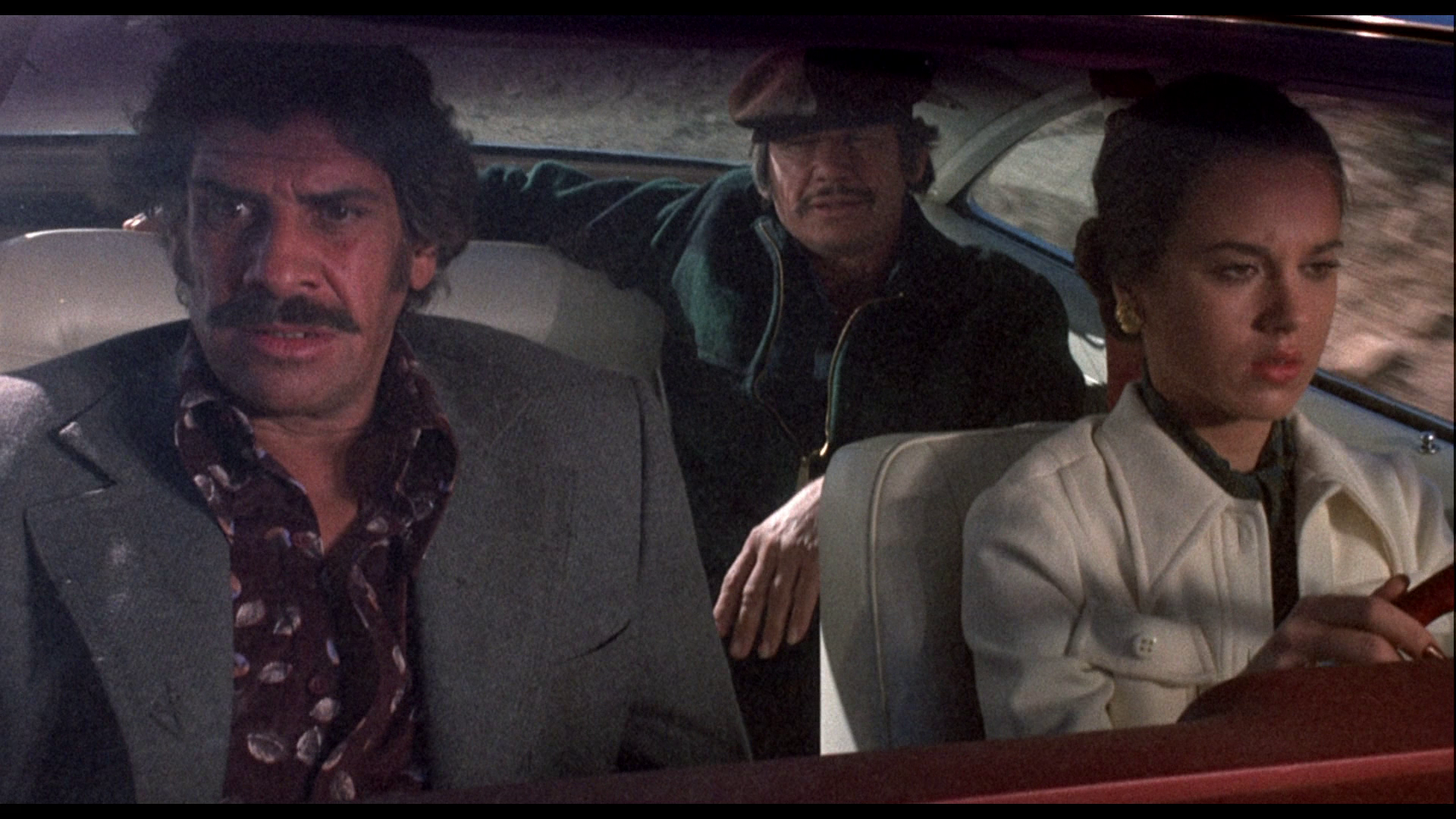

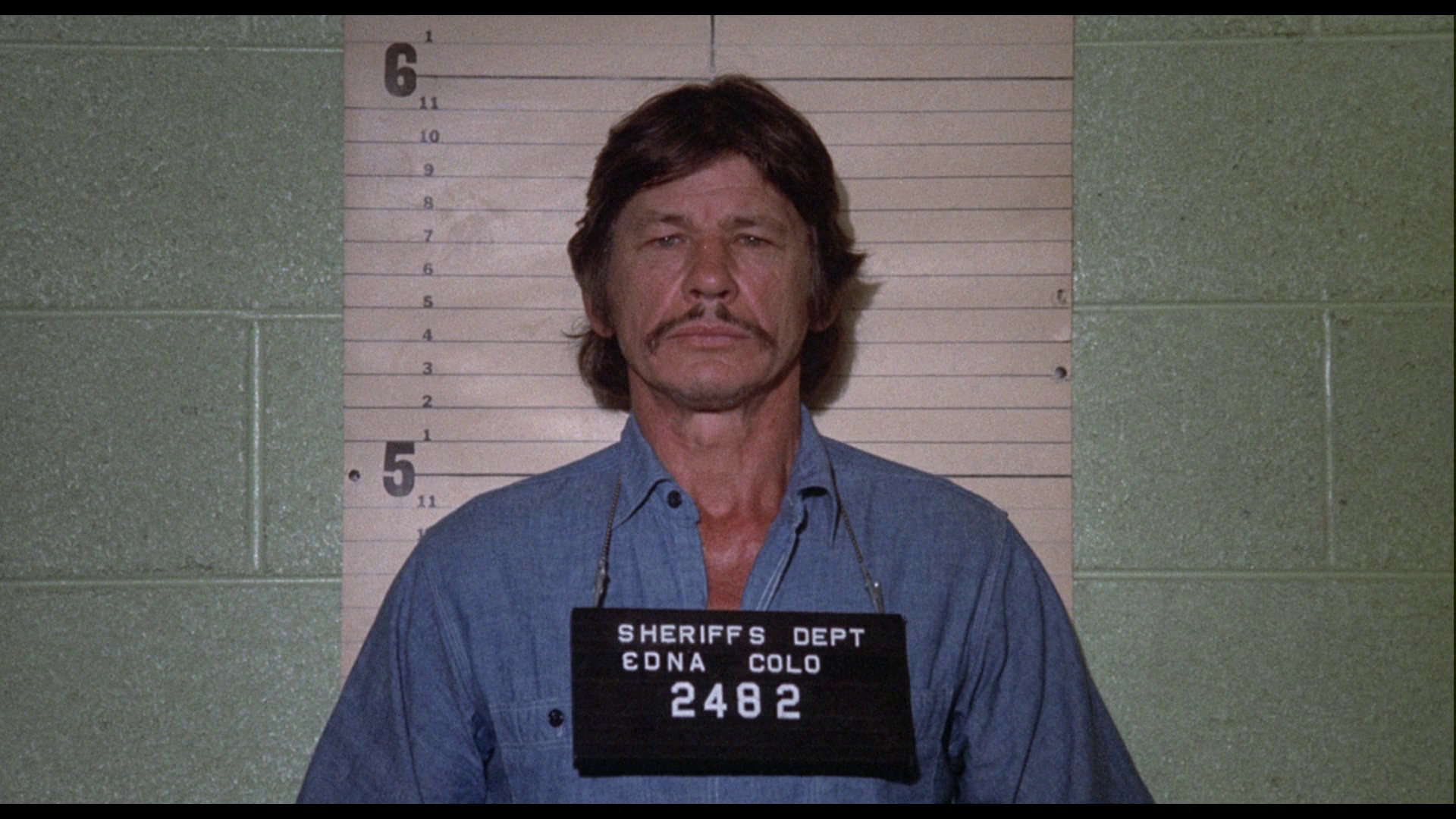

However, Majestyk is soon arrested by the local police when Kopas claims that Majestyk assaulted him. Majestyk is questioned by Detective Lieutenant McAllen (Frank Maxwell), who becomes aware that Majestyk is a war hero, the winner of a Silver Star; however, Majestyk has already served a prison sentence (in Folsom) for assault, and this causes McAllen to treat the farmer with suspicion. (It’s also revealed that whilst Majestyk was in Folsom, his wife left him.) Whilst in the cells, Majestyk encounters Frank Renda (Al Lettieri), a hitman for the mob. As the prisoners are being transported via bus, Renda’s associates stage a breakout, using firearms to halt the bus. During the confusion, Majestyk manages to free himself, driving the bus away and taking Renda hostage. Majestyk’s plan is to make a deal with the police: he will return Renda to their custody in exchange for the charges against himself being dropped. However, with the aid of his moll Wiley (Lee Purcell), Renda manages to escape from Majestyk’s grasp but vows to kill the melon farmer. Cognisant of Renda’s vow to murder Majestyk, the police use Majestyk as bait, hoping to lure Renda into the open. The dialogue for Mr Majestyk has ‘Dutch’s trademark snappiness. During their first encounter, Majestyk asks Nancy, ‘You looking for work?’ To this, she responds sarcastically: ‘Well, we forgot our golf clubs, so we might as well’. Later, towards the end of the film, Renda confronts Majestyk directly, telling the melon farmer ‘I’m gonna kill you’. ‘When is this big event going to take place?’, Majestyk asks. ‘What’s the difference?’, Renda reasons, ‘Tomorrow, next week. You can hide in the basement of that police station, but I’m gonna get you, my baby’. ‘Seems like there’s no use trying to get on your good side’, Majestyk quips.  Chip Rhodes suggests that Mr Majestyk has some similarities with the Western Joe Kidd (John Sturges, 1972), for which Leonard also wrote the screenplay. In both films, Leonard ‘treats the police and the legal system with much less respect than he would in his later crime fiction’ (Rhodes, 2008: 143). The police ‘are peripheral to the central conflict’, and offer ‘a hindrance more than anything else’ (ibid.). The true antagonist within the film, Renda, ‘is tied to the forces that wish to control the workforce in a way that is reminiscent of On the Waterfront’ (ibid.). However, where Budd Schulberg’s script for On the Waterfront ‘conflated the mob and the unions, absented the capitalists, and championed the disaffected individual’, Mr Majestyk ‘made the mob the enemy of both the unions and the disaffected individual [Majestyk], who also happens to be the capitalist’ (ibid.; emphasis in original). After picking up Nancy, Majestyk talks with her as they drive back to his farm. Nancy tells Majestyk that she works for the union; she’s somewhat surprised to find that Majestyk – the employer – is okay with this. ‘I don’t care if you work for the union or you don’t work for the union’, he tells her, ‘as long as you know melons’. Towards the end of the film, whilst he is being used by the police as bait to lure in Renda, Majestyk is shown working in the fields with his employees, golden light behind him; it’s an idealistic scenario of solidarity between worker and employer that underscores the sense of equality that Majestyk represents. Chip Rhodes suggests that Mr Majestyk has some similarities with the Western Joe Kidd (John Sturges, 1972), for which Leonard also wrote the screenplay. In both films, Leonard ‘treats the police and the legal system with much less respect than he would in his later crime fiction’ (Rhodes, 2008: 143). The police ‘are peripheral to the central conflict’, and offer ‘a hindrance more than anything else’ (ibid.). The true antagonist within the film, Renda, ‘is tied to the forces that wish to control the workforce in a way that is reminiscent of On the Waterfront’ (ibid.). However, where Budd Schulberg’s script for On the Waterfront ‘conflated the mob and the unions, absented the capitalists, and championed the disaffected individual’, Mr Majestyk ‘made the mob the enemy of both the unions and the disaffected individual [Majestyk], who also happens to be the capitalist’ (ibid.; emphasis in original). After picking up Nancy, Majestyk talks with her as they drive back to his farm. Nancy tells Majestyk that she works for the union; she’s somewhat surprised to find that Majestyk – the employer – is okay with this. ‘I don’t care if you work for the union or you don’t work for the union’, he tells her, ‘as long as you know melons’. Towards the end of the film, whilst he is being used by the police as bait to lure in Renda, Majestyk is shown working in the fields with his employees, golden light behind him; it’s an idealistic scenario of solidarity between worker and employer that underscores the sense of equality that Majestyk represents.

Arriving back at the farm with Nancy and his new crew, Majestyk soon runs into Bobby Kopas, who uses strongarm tactics to try to ‘persuade’ Majestyk into employing the men that he’s gathered. (Kopas considers himself to be a gangster of sorts, but this is undermined when he comes into conflict with the real gangster, Frank Renda, later in the film.) Kopas already has a crew working in Majestyk’s fields, and introduces himself: ‘Bobby Kopas. Come over form La Junta with some top hand pickers’. ‘I don’t hire winos who’ve never slipped melons before’, Majestyk asserts quietly. ‘I don’t know. You hire a lot of Latins and no whites’, Kopas declares, ‘Looks like discrimination to me’; he asks Majestyk, ‘What do you care who works for you, as long as you get the job done?’ In response to this, Majestyk asserts his autonomy and his independence: ‘I hire who I want’. ‘Yeah, well, you see, you want me. Only it ain’t sunk into that thick brain of yours yet. See, everything goes a lot easier – a lot less trouble when you do business with me’. In response to this, Majestyk challenges Kopas directly, delivering a threat with quiet but assured conviction: ‘You make sounds like you’re a mean little ass-kicker’, Majestyk says, ‘only I ain’t convinced. You keep talking, I’m going to take your head off’.  Although Koslo is a small-time crook and Renda is a killer with ties to the syndicate, Majestyk refuses to be intimidated by either. ‘You got it ass backwards’, Majestyk tells Renda when Renda’s associates attempt to stage Renda’s escape, ‘I ain’t coming with you: you’re coming with me’. (For his part, Renda tells Majestyk, ‘I had you figured for the local clown, but you really move’.) Later, Renda tries to persuade Majestyk to take him to Los Angeles; he promises Majestyk that in LA they could ‘get a couple broads in’ before heading for Mexico City. However, Majestyk tells Renda quite simply that ‘I been to LA, and I been to Mexico… And I been laid’. ‘Then what do you want?’, Renda asks. ‘To get a melon crop in’, Majestyk asserts. (When he returns to his farm later, Majestyk is mocked by Kopas: ‘You know, I think you’re messed up’, Kopas says, ‘standing there in deep shit, and all you’re worried about is your melon crop’.) Melons in the film seem to take on the value (both financial and symbolic) of the prized ‘Golden Delish’ apples that Richard Conte’s character is transporting in Jules Dassin’s classic film noir Thieves’ Highway (1950). Speaking to Renda, Kopas tells the hitman that Majestyk is ‘a stuck-up son of a bitch. Got a crop of melons; thinks he’s the big roar’. Although Koslo is a small-time crook and Renda is a killer with ties to the syndicate, Majestyk refuses to be intimidated by either. ‘You got it ass backwards’, Majestyk tells Renda when Renda’s associates attempt to stage Renda’s escape, ‘I ain’t coming with you: you’re coming with me’. (For his part, Renda tells Majestyk, ‘I had you figured for the local clown, but you really move’.) Later, Renda tries to persuade Majestyk to take him to Los Angeles; he promises Majestyk that in LA they could ‘get a couple broads in’ before heading for Mexico City. However, Majestyk tells Renda quite simply that ‘I been to LA, and I been to Mexico… And I been laid’. ‘Then what do you want?’, Renda asks. ‘To get a melon crop in’, Majestyk asserts. (When he returns to his farm later, Majestyk is mocked by Kopas: ‘You know, I think you’re messed up’, Kopas says, ‘standing there in deep shit, and all you’re worried about is your melon crop’.) Melons in the film seem to take on the value (both financial and symbolic) of the prized ‘Golden Delish’ apples that Richard Conte’s character is transporting in Jules Dassin’s classic film noir Thieves’ Highway (1950). Speaking to Renda, Kopas tells the hitman that Majestyk is ‘a stuck-up son of a bitch. Got a crop of melons; thinks he’s the big roar’.

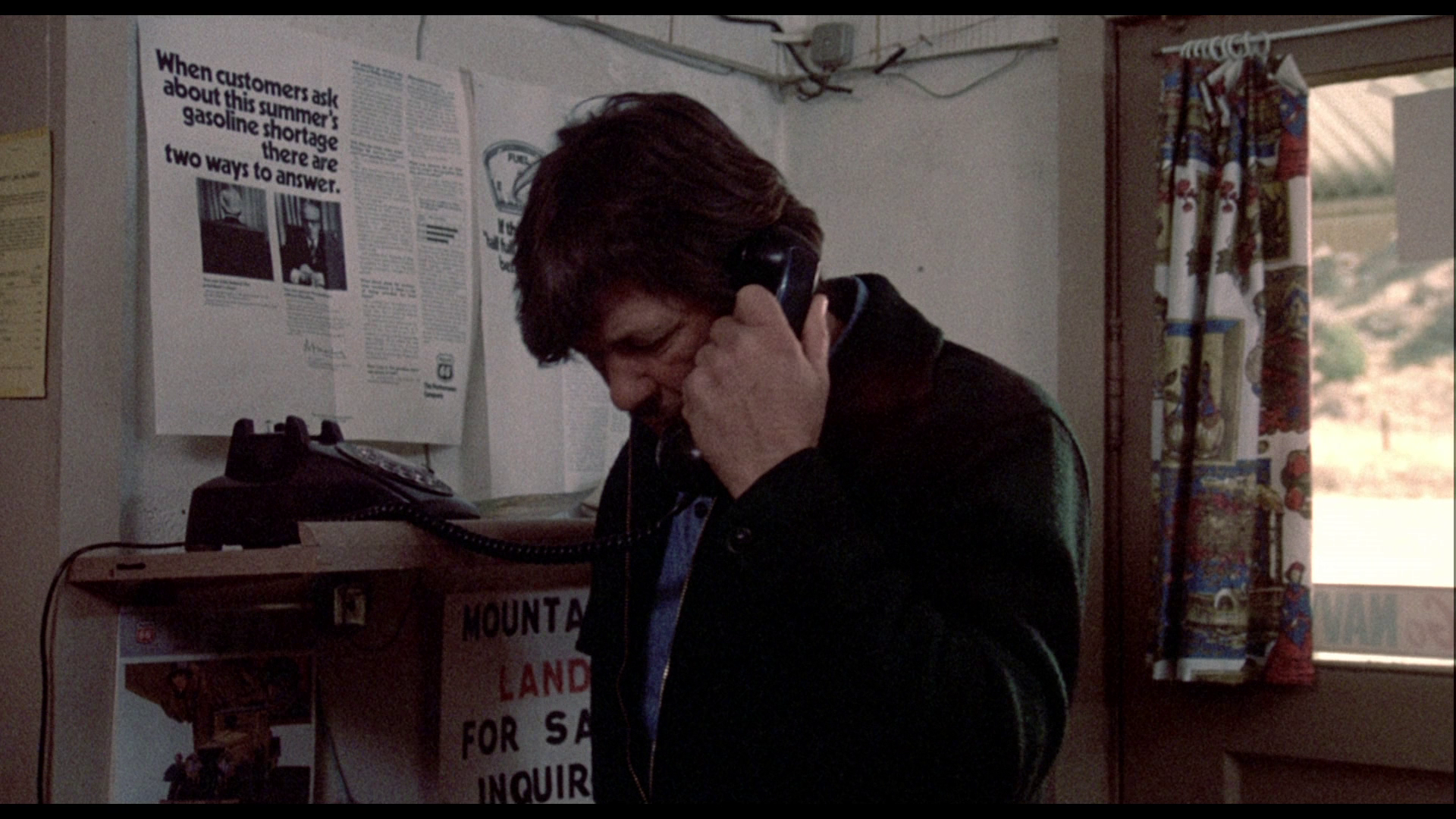

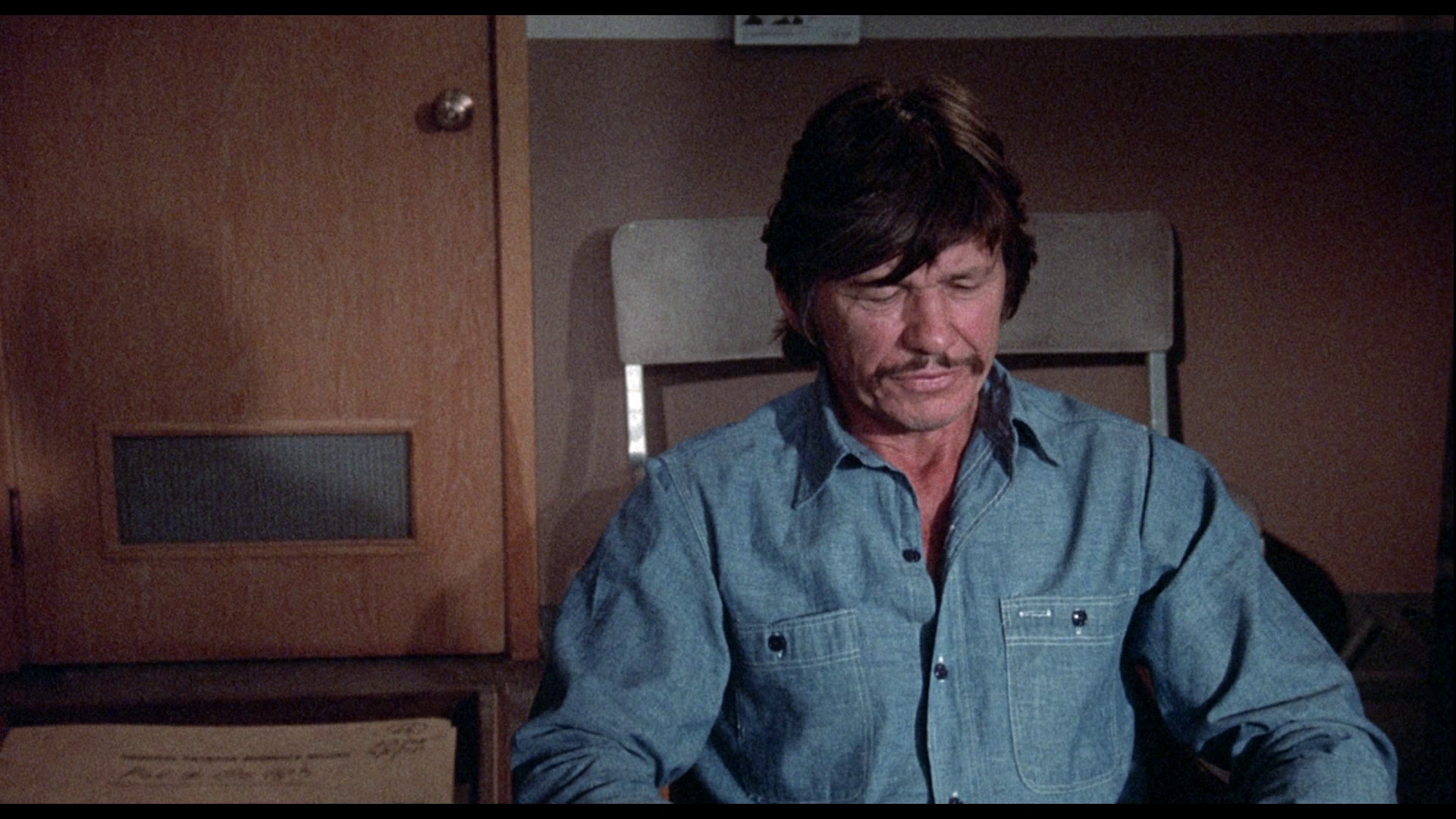

Meanwhile, Majestyk is equally distrusting of the police. Taken into custody after Kopas claims that Majestyk assaulted him, Majestyk is asked by McAllen, ‘You understand your rights under the law?’ ‘I understand I should keep my mouth shut’, Majestyk responds, ‘That seems to be about it’. Later, Majestyk blows his cool for the only time in the picture when he calls McAllen to offer Renda in exchange for the assault charges against Majestyk to be dropped. Speaking on the telephone, McAllen says, ‘You mean, you’re gonna sell him [Renda] to us’. To this, Majestyk responds angrily, ‘Well, there ain’t nothing that’s free in this world’. Later, after Renda has escaped from him, Majestyk is allowed by the police to return to his farm – as bait for Renda. ‘Why is it I get a feeling from you that you hope he [Renda] pulls it off, just so you can get him for murder?’, Majestyk asks McAllen. Later, Majestyk turns down police protection, and McAllen warns him, ‘You’re not going to get those melons picked if you’re dead’. ‘If I’m dead, it won’t matter, will it?’, Majestyk reasons. ‘Suit yourself’, McAllen asserts, ‘but you’re on your own’. ‘Lieutenant, I’ve been on my own from the very beginning’, Majestyk declares bitterly.  Emmett Early suggests that Mr Majestyk ‘flirts with satire as Majestyk talks repeatedly about only wanting to harvest his melons, and when the gangsters with automatic rifles shoot up the crop, splattering red flesh from exploding fruit, it seems the melons take on the overdeveloped role of symbol, more than just the honest rewards of a poor man’s labors’ (Early, op cit.: 162). Certainly, there’s much humour in Majestyk’s repeated protestations – first to the police, and later to Renda – that all he wants to do is return home to his farm to take care of his melons. When arrested by the police, Majestyk tells McAllen he needs to return home to his farm to tend to his watermelons. ‘That’s all that’s worrying you? Melons?’, McAllen asks in disbelief. When, near the film’s climax, Renda and his gang chase off Majestyk’s employees, they also attempt to destroy Majestyk’s precious melon crop. Renda begins by firing his revolver into the melons. A shot of the melons shows the bullets biting into them, splitting open the green rind to reveal the pink flesh within: as they burst open, they seem to act as a metonym for the human body and its vulnerability, the red of the flesh within the melon reminiscent of our own internal organs. Renda then orders his men to shoot into the crop using submachine guns. The men fire into the melons in slow-motion, their bullets tearing through the fruit. The scene is both blackly comic and openly symbolic, the imagery (armed men firing into a passive, helpless target) seemingly using the melons as paradigms to refer obliquely to the imagery within photography and newsreel footage depicting roughly contemporaneous events such as the shootings at Kent State University, the massacre at My Lai, and images of the massacring of civilians in numerous other conflicts both before and, sadly, since the film’s release. Emmett Early suggests that Mr Majestyk ‘flirts with satire as Majestyk talks repeatedly about only wanting to harvest his melons, and when the gangsters with automatic rifles shoot up the crop, splattering red flesh from exploding fruit, it seems the melons take on the overdeveloped role of symbol, more than just the honest rewards of a poor man’s labors’ (Early, op cit.: 162). Certainly, there’s much humour in Majestyk’s repeated protestations – first to the police, and later to Renda – that all he wants to do is return home to his farm to take care of his melons. When arrested by the police, Majestyk tells McAllen he needs to return home to his farm to tend to his watermelons. ‘That’s all that’s worrying you? Melons?’, McAllen asks in disbelief. When, near the film’s climax, Renda and his gang chase off Majestyk’s employees, they also attempt to destroy Majestyk’s precious melon crop. Renda begins by firing his revolver into the melons. A shot of the melons shows the bullets biting into them, splitting open the green rind to reveal the pink flesh within: as they burst open, they seem to act as a metonym for the human body and its vulnerability, the red of the flesh within the melon reminiscent of our own internal organs. Renda then orders his men to shoot into the crop using submachine guns. The men fire into the melons in slow-motion, their bullets tearing through the fruit. The scene is both blackly comic and openly symbolic, the imagery (armed men firing into a passive, helpless target) seemingly using the melons as paradigms to refer obliquely to the imagery within photography and newsreel footage depicting roughly contemporaneous events such as the shootings at Kent State University, the massacre at My Lai, and images of the massacring of civilians in numerous other conflicts both before and, sadly, since the film’s release.

In The War Veteran in Film, Emmett Early compares Mr Majestyk to First Blood (George P Cosmatos, 1982) and Clint Eastwood’s Absolute Power (1997). All three of these films feature war veterans whose status as such is revealed when they come into conflict with the law (Early, 2003: 106, 211). The trailer for Mr Majestyk compares the picture to another couple of films: Walking Tall (Phil Karlson, 1973) and Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin, 1971), the two iconic rural/small town-set vigilante films of the early 1970s. Other than the theme of vigilantism and the small town setting, Walking Tall and Billy Jack are very different films: the protagonist of Walking Tall is a sheriff, a member of the ‘establishment’; the hero of Billy Jack is an outsider, a veteran of the Vietnam War who is nevertheless a pacifist, and as a Native American a member of a persecuted group. In truth, Mr Majestyk is similar to Billy Jack: like Billy Jack, Majestyk is a war veteran, and although he isn’t a member of a persecuted minority group, from the outset he’s established as a man who defends the persecuted. From the opening sequence, Majestyk is depicted as a character – though he’s a landowner – who will fight for the underdog. He chooses to employ migrant workers, hiring them at $1.40 an hour, which is more than the $1.20 that Kopas has promised the men he’s trying to railroad Majestyk into employing. As the men line up and Majestyk picks them for labour, Majestyk tells the man who has brought the labourers to Majestyk that ‘We’re paying a buck-forty a day, ten hour day, and don’t you short change them’. He witnesses prejudice in action when a group of Mexican-Americans, including Nancy Chavez, arrive at the gas station where Majestyk is filling up. The gas station employee refuses to allow the Mexican-Americans to use the toilets. Nancy protests, telling the man that they will enter the toilets one by one – so he’s sure that Nancy isn’t using the toilets to prostitute herself to the men, which is what the gas station employee seems to believe is taking place. Majestyk intervenes on behalf of the Mexican-Americans. The gas station employee takes Majestyk to one side and tells him, ‘Listen, you know how many migrants stop by here? These people, they get in there [the lavatory], take a bath, mess the place up, steal the toilet paper’. ‘Let them use it’, Majestyk insists quietly but firmly, ‘You said someone else owned the place. What do you care if they use the toilet or not?’ In The War Veteran in Film, Emmett Early compares Mr Majestyk to First Blood (George P Cosmatos, 1982) and Clint Eastwood’s Absolute Power (1997). All three of these films feature war veterans whose status as such is revealed when they come into conflict with the law (Early, 2003: 106, 211). The trailer for Mr Majestyk compares the picture to another couple of films: Walking Tall (Phil Karlson, 1973) and Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin, 1971), the two iconic rural/small town-set vigilante films of the early 1970s. Other than the theme of vigilantism and the small town setting, Walking Tall and Billy Jack are very different films: the protagonist of Walking Tall is a sheriff, a member of the ‘establishment’; the hero of Billy Jack is an outsider, a veteran of the Vietnam War who is nevertheless a pacifist, and as a Native American a member of a persecuted group. In truth, Mr Majestyk is similar to Billy Jack: like Billy Jack, Majestyk is a war veteran, and although he isn’t a member of a persecuted minority group, from the outset he’s established as a man who defends the persecuted. From the opening sequence, Majestyk is depicted as a character – though he’s a landowner – who will fight for the underdog. He chooses to employ migrant workers, hiring them at $1.40 an hour, which is more than the $1.20 that Kopas has promised the men he’s trying to railroad Majestyk into employing. As the men line up and Majestyk picks them for labour, Majestyk tells the man who has brought the labourers to Majestyk that ‘We’re paying a buck-forty a day, ten hour day, and don’t you short change them’. He witnesses prejudice in action when a group of Mexican-Americans, including Nancy Chavez, arrive at the gas station where Majestyk is filling up. The gas station employee refuses to allow the Mexican-Americans to use the toilets. Nancy protests, telling the man that they will enter the toilets one by one – so he’s sure that Nancy isn’t using the toilets to prostitute herself to the men, which is what the gas station employee seems to believe is taking place. Majestyk intervenes on behalf of the Mexican-Americans. The gas station employee takes Majestyk to one side and tells him, ‘Listen, you know how many migrants stop by here? These people, they get in there [the lavatory], take a bath, mess the place up, steal the toilet paper’. ‘Let them use it’, Majestyk insists quietly but firmly, ‘You said someone else owned the place. What do you care if they use the toilet or not?’

Although the events are set in motion by Kopas, Renda is the heavy here, and as Barry Gifford has noted the character Lettieri plays in Mr Majestyk is ‘basically the same role’ he played in Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 adaptation of Jim Thompson’s The Getaway: ‘cruel as Basil Rathbone in Tower of London or Laurence Olivier in Richard III. (The difference is that neither Rathbone nor Olivier wore an Italian fruit-peddler mustache.)’ (Gifford, 2001: 117). Lettieri’s character, the mob hitman named Randa, is for Gifford ‘absolutely, thoroughly believable’ (ibid.). As the narrative progresses, building towards the final confrontation between Majestyk and Renda, Barry Gifford suggests that the film ‘gains a curious sort of gracefulness […] a rhythm almost imperceptible at first, but once you see how action and landscape are wedded, it’s easy to watch even with the sound turned off’ (Gifford, op cit.: 117). ‘If Peckinpah had made it’, Gifford argues, ‘movie lizards would consider Mr Majestyk a masterpiece’ (ibid.). Although the events are set in motion by Kopas, Renda is the heavy here, and as Barry Gifford has noted the character Lettieri plays in Mr Majestyk is ‘basically the same role’ he played in Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 adaptation of Jim Thompson’s The Getaway: ‘cruel as Basil Rathbone in Tower of London or Laurence Olivier in Richard III. (The difference is that neither Rathbone nor Olivier wore an Italian fruit-peddler mustache.)’ (Gifford, 2001: 117). Lettieri’s character, the mob hitman named Randa, is for Gifford ‘absolutely, thoroughly believable’ (ibid.). As the narrative progresses, building towards the final confrontation between Majestyk and Renda, Barry Gifford suggests that the film ‘gains a curious sort of gracefulness […] a rhythm almost imperceptible at first, but once you see how action and landscape are wedded, it’s easy to watch even with the sound turned off’ (Gifford, op cit.: 117). ‘If Peckinpah had made it’, Gifford argues, ‘movie lizards would consider Mr Majestyk a masterpiece’ (ibid.).

The film, as presented here, is uncut and runs for 103:38 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, Signal One’s presentation of Mr Majestyk is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. It’s an excellent presentation, clean and free of damage and debris, the strong colour reproduction evident from the film’s title sequence – in which images from the film are presented as still frames using the colours red and black. Skin tones are natural and consistent. The photography in the film is excellent; as the film builds towards its climax, longer focal lengths are used to flatten perspective and give the impression of the characters (Renda and Majestyk, particularly) seeming larger than life. The harsh sunlight of the setting results in bold contrast, which is carried through this presentation via excellent contrast levels, which offer a very pleasantly-balanced image. A strong level of detail is evident throughout, much improved over the film’s DVD incarnations. A strong encode ensures that the picture retains the organic structure of 35mm film. Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, Signal One’s presentation of Mr Majestyk is in 1080p and uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. It’s an excellent presentation, clean and free of damage and debris, the strong colour reproduction evident from the film’s title sequence – in which images from the film are presented as still frames using the colours red and black. Skin tones are natural and consistent. The photography in the film is excellent; as the film builds towards its climax, longer focal lengths are used to flatten perspective and give the impression of the characters (Renda and Majestyk, particularly) seeming larger than life. The harsh sunlight of the setting results in bold contrast, which is carried through this presentation via excellent contrast levels, which offer a very pleasantly-balanced image. A strong level of detail is evident throughout, much improved over the film’s DVD incarnations. A strong encode ensures that the picture retains the organic structure of 35mm film.

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. It’s not a ‘showy’ track by any means, though it showcases the film’s score (by Charles Bernstein) well. The track displays good range where it needs to (in gunshots, for example) and is clear and audible throughout. The optional subtitles are easy to read and grammatically correct.

Extras

The disc includes:  - an audio commentary by Paul Talbot. Talbot, the author of the excellent books Bronson’s Loose: The Making of the Death Wish Films and Bronson’s Loose Again: On Set with Charles Bronson, offers an enthusiastic discussion of the film that is filled with interesting observations and anecdotes about this and other Bronson pictures. It’s an excellent commentary track, which for a fan of Bronson’s films is much fun to listen to. - an audio commentary by Paul Talbot. Talbot, the author of the excellent books Bronson’s Loose: The Making of the Death Wish Films and Bronson’s Loose Again: On Set with Charles Bronson, offers an enthusiastic discussion of the film that is filled with interesting observations and anecdotes about this and other Bronson pictures. It’s an excellent commentary track, which for a fan of Bronson’s films is much fun to listen to.

Two interviews: - ‘Colorado Cool’ (14:00). Here in a new interview, Richard H Kline, the film’s director of photography, reflects on his experiences during the making of the picture. Kline asserts that Mr Majestyk ‘is a film with a lot of action, really good action’. Kline reflects on the shooting of some specific sequences, discussing his approach to photographing the film. - ‘Colorado Chic’ (27:56). This new interview with Lee Purcell sees the actress expressing some surprise at the cult following that Mr Majestyk has attracted in the years since its original release. Purcell discusses her acting work prior to Mr Majestyk, including Dirty Little Billy and Kid Blue. Purcell talks about how she came to act in the film after initially turning the part down. She reflects on the making of the film, and tells a story of Bronson ‘in his quiet, but super-menacing way, that you did see on film’ protected Purcell when somebody involved in the production threatened her. Purcell also talks about her approach to the character of Wiley, which included carrying a bible with her at all times. - Lobby Cards, Posters and Stills Gallery (0:52). - Trailer (1:33).

Overall

Mr Majestyk is a wildly entertaining film, thanks in large part of Leonard’s snappy script and the interplay between Bronson and Lettieri. The picture is filled with some very good actors in smaller parts too, including Koslo, Purcell and Cristal. At the time of production, Bronson asserted that Mr Majestyk required him to do ‘something I haven’t done for a while – acting. It [the film] has that, too, besides the action’ (D’Ambrosio, op cit.: 149). The picture certainly gives Bronson an interesting character to play, and he handles the character’s transition from moments of quiet watchfulness to explosions of violence very well. The film seems to strive for symbolism in its depiction of Majestyk’s desperate attempts to gather and protect his crop of melons, and in some ways the picture offers a strange and enticing mixture of social issues not usually explored in Hollywood films (the positive depiction of migrant workers, Majestyk’s sympathetic treatment of them) and some very impressive action setpieces. Aside from the casting of Lettieri, the picture also has a very Peckinpah-esque feel to it, and it’s difficult not to agree with Gifford – that if it was a film with the name of a filmmaker like Peckinpah attached to it (rather than a supposed ‘journeyman’ like Fleischer), it would be much more highly regarded. Mr Majestyk is a wildly entertaining film, thanks in large part of Leonard’s snappy script and the interplay between Bronson and Lettieri. The picture is filled with some very good actors in smaller parts too, including Koslo, Purcell and Cristal. At the time of production, Bronson asserted that Mr Majestyk required him to do ‘something I haven’t done for a while – acting. It [the film] has that, too, besides the action’ (D’Ambrosio, op cit.: 149). The picture certainly gives Bronson an interesting character to play, and he handles the character’s transition from moments of quiet watchfulness to explosions of violence very well. The film seems to strive for symbolism in its depiction of Majestyk’s desperate attempts to gather and protect his crop of melons, and in some ways the picture offers a strange and enticing mixture of social issues not usually explored in Hollywood films (the positive depiction of migrant workers, Majestyk’s sympathetic treatment of them) and some very impressive action setpieces. Aside from the casting of Lettieri, the picture also has a very Peckinpah-esque feel to it, and it’s difficult not to agree with Gifford – that if it was a film with the name of a filmmaker like Peckinpah attached to it (rather than a supposed ‘journeyman’ like Fleischer), it would be much more highly regarded.

Signal One are rapidly becoming a label to watch, their releases offering excellent presentations and some superb contextual material. Their Blu-ray release of Mr Majestyk is no exception, offering a very pleasing presentation of the main feature and some very good extra features. The commentary from Talbot is superb, as are the new interviews with Kline and Purcell. For Bronson/Fleischer/Leonard fans (or fans of action films of the era more generally), this release is an essential purchase. References: Challen, Paul Clarence, 2000: Get Dutch! A Biography of Elmore Leonard. Ontario: ECW Press D’Ambrosio, Brian, 2012: Menacing Face Worth Millions: A Life of Charles Bronson. Lulu.com Early, Emmett, 2003: The War Veteran in Film. London: McFarland and Company Gifford, Barry, 2001: Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir. University Press of Mississippi LoCicero, Tony, 2014: Dutch on Dutch: One of the Last Interviews with the Incomparable Elmore Leonard. TLC Media Rhodes, Chip, 2008: Politics, Desire and the Hollywood Novel. University of Iowa Press

|

|||||

|