|

The Film

Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol 1 Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol 1

Voice Without a Shadow (Suzuki Seijun, 1958)

Red Pier (AKA Red Quay)

The Rambling Guitarist (AKA Guitar Wanderer)

Representing the early years of Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon (‘borderless action’) pictures, the three films in this collection highlight the studio’s attempt to appeal to a youth market by taking influences (both thematic and visual, in terms of their use of chiaroscuro lighting and obtuse angles and compositions) from American films noir, the youth films popular during the 1950s and 1960s, American ‘adult’ Westerns of the 1950s and, in later examples of the form’s ‘Servant of Two Masters’-type plots, westerns all’italiana like Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Nikkatsu’s action pictures of this period had an ‘international’ flavour that led to them being labelled as ‘borderless’ action films, and the films themselves were predominantly tailored towards a young audience.

Nikkatsu’s trend in producing youth-oriented mukokuseki akushon pictures began in 1956 with Furukawa Takumi’s Season of the Sun. Drawing from European and American cinema, the films borrowed something of the individualism and film noir sensibility of American films and mixed it with the experimentation and existential dilemmas found within many European ‘New Wave’ cinemas. This was heightened in the 1960s, a time when some of the filmmakers within the Nikkatsu ‘stable’ demonstrated a strong sense of invention: Suzuki Seijun is possibly the most famous example, given the outrageous experimentation within his anarchic 1967 picture Branded to Kill which led to him being fired by Nikkatsu. Having worked as a director for Nikkatsu since his debut feature Victory is Mine in 1954, Suzuki was hired to direct Branded to Kill at the last minute and turned in a picture that, to Nikkatsu’s bosses, was deliberately ‘incomprehensible’ (Sharp, op cit.: 182). Branded to Kill may be considered a subversive self-parody of the mukokuseki akushon pictures; Nikkatsu terminated Suzuki’s contract illegally, and when Suzuki struck back by suing Nikkatsu, leading to him being effectively blacklisted for the next ten years, he consolidated his position as a countercultural figure.

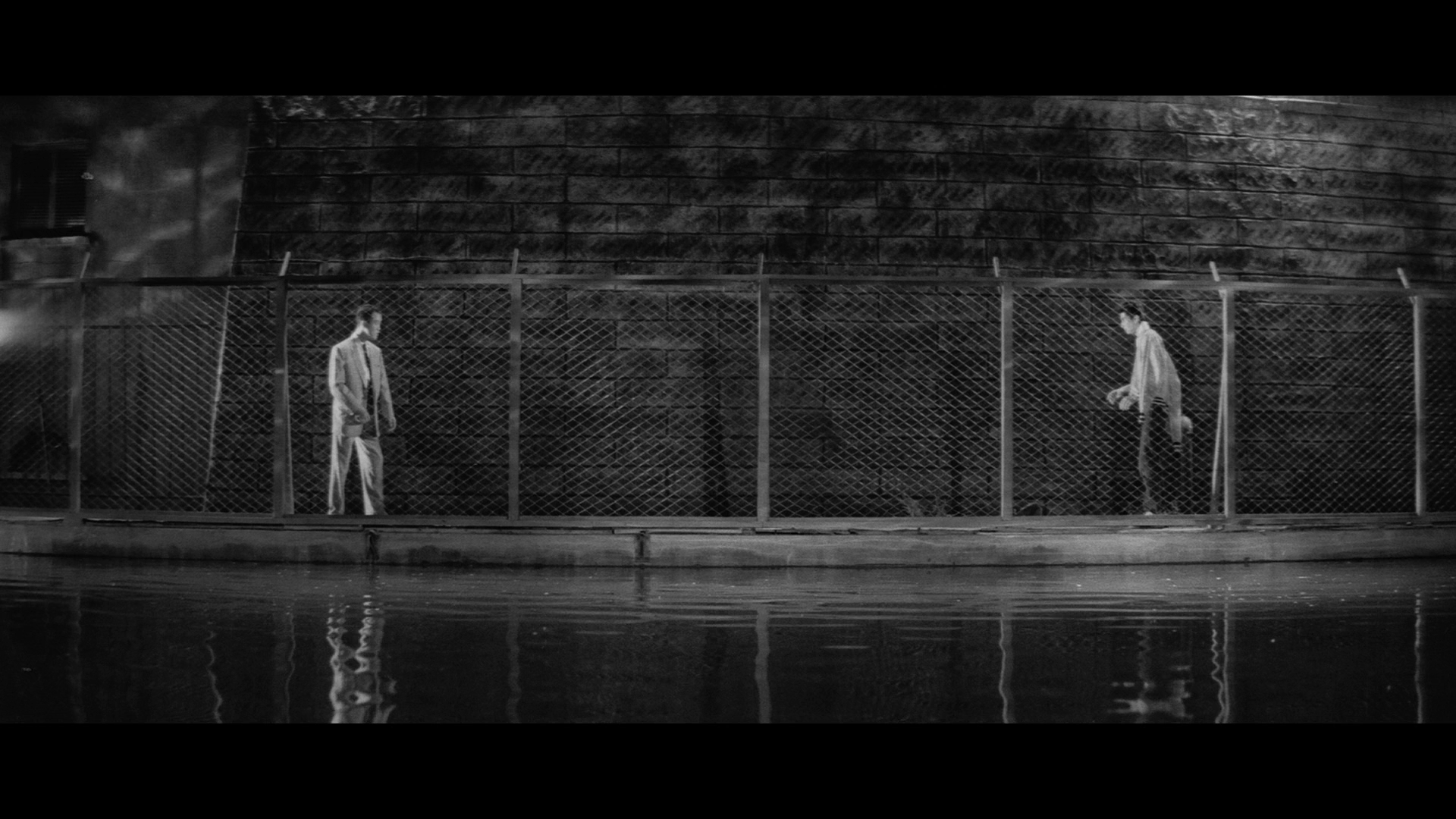

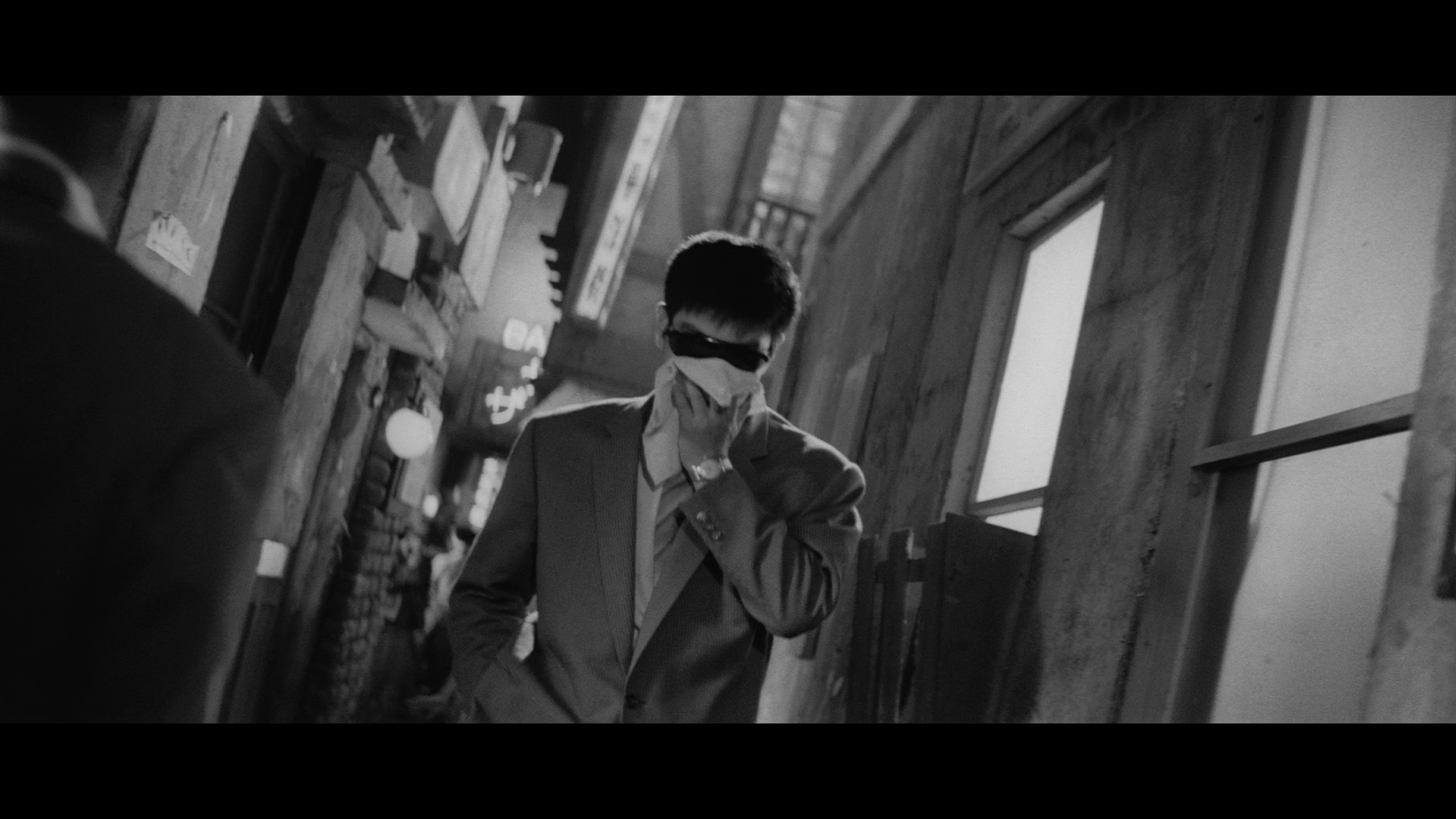

Reflecting their ‘borderless’ qualities, Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon films featured individualistic heroes, often gangsters or policemen, who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes shot in film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting. In previous Japanese films, the yakuza had appeared - but usually in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). In earlier yakuza films, the villains were often Westernised, and in contrast with these Westernised characters the moral code of the yakuza would usually be depicted in a positive light. Nikkatsu’s borderless action films, with their contemporary urban settings and their morally-conflicted and Westernised heroes (rather than villains), were in stark contrast with these earlier yakuza pictures. In comparison with the earlier yakuza films with a period setting, the Nikkatsu films of the 1960s often featured an implicit critique of the code of the yakuza that was buried within an exploration of inter-generational conflict, with the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans frequently depictured as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mukokuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182). Reflecting their ‘borderless’ qualities, Nikkatsu’s mukokuseki akushon films featured individualistic heroes, often gangsters or policemen, who drank whisky in jazz clubs and skulked through scenes shot in film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting. In previous Japanese films, the yakuza had appeared - but usually in jidaigeki pictures (period dramas). In earlier yakuza films, the villains were often Westernised, and in contrast with these Westernised characters the moral code of the yakuza would usually be depicted in a positive light. Nikkatsu’s borderless action films, with their contemporary urban settings and their morally-conflicted and Westernised heroes (rather than villains), were in stark contrast with these earlier yakuza pictures. In comparison with the earlier yakuza films with a period setting, the Nikkatsu films of the 1960s often featured an implicit critique of the code of the yakuza that was buried within an exploration of inter-generational conflict, with the elderly male leaders of yakuza clans frequently depictured as corrupt, corporate oligarchs who victimise the more forward-thinking and youthful heroes, exploiting the protagonists’ sense of loyalty to the hierarchies of the yakuza. However, as Jasper Sharp has noted, despite their modern-day settings, the mukokuseki akushon pictures ‘bore little resemblance to any contemporary Japanese reality’ (Sharp, 2011: 182).

As the 1960s progressed, Nikkatsu’s action films became increasingly moody, some of them evolving into what were labeled as mudo akushon (‘mood action’) films. As cinema audiences dwindled during the late-1960s, these gave way to a new subgenre of nyu akushon (‘new action’) films, which were increasingly violent and featured protagonists who were morally-ambiguous. In the 1970s, these would be supplanted by the jitsuroku films. The jitsuroku pictures used documentary filmmaking techniques (handheld camerawork, abrupt editing rhythms) and depicted the yakuza as little more than street thugs motivated solely by self-interest. (Fukasaku Kinji’s 1973 film Battles Without Honour and Humanity is often cited as one of the earliest examples of the jitsuroku subgenre.) During the same era, as cinema audiences continued to decline, Nikkatsu turned its attention away from the gangster films and youth comedies that had been its forte since the mid-1950s and began to focus on the production of Roman Porno films – erotic pictures that subsequently came to define the Nikkatsu ‘brand’ for many years to come.

The three films in Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guys boxed set represent the early years of Nikkatsu’s borderless action phase, three pictures that in one way or another reflect the international flavour of Nikkatsu’s youth-oriented pictures of the period. The first picture in this set is Suzuki Seijun’s Voice Without a Shadow, one of four films that Suzuki made for Nikkatsu in 1958 and a picture which underscores the similarities between Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ productions and American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s. The three films in Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guys boxed set represent the early years of Nikkatsu’s borderless action phase, three pictures that in one way or another reflect the international flavour of Nikkatsu’s youth-oriented pictures of the period. The first picture in this set is Suzuki Seijun’s Voice Without a Shadow, one of four films that Suzuki made for Nikkatsu in 1958 and a picture which underscores the similarities between Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless’ productions and American films noir of the 1940s and 1950s.

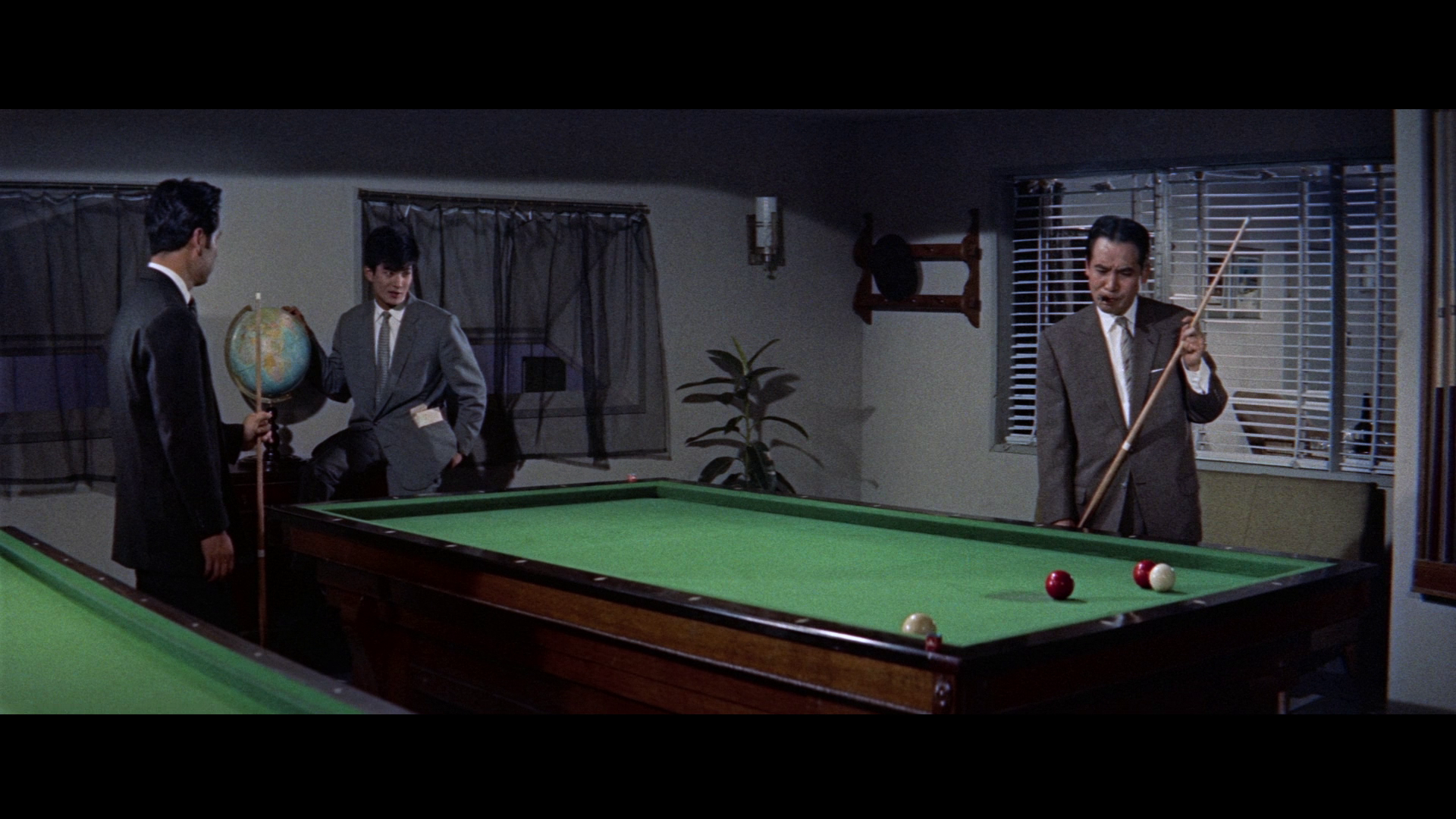

Voice Without a Shadow begins with Takahashi Asako, a telephone switchboard operator for the Maicho newspaper, accidentally overhearing a murder when she connects to a line; she is subsequently mocked over the telephone by the killer, who tells Asako that she has connected to a crematory. Three years later, Ishikawa, one of the reporters for the newspaper, spots Asako. She is now a housewife, downtrodden and trapped within the domestic sphere. Her husband is Kotani Shigeo. Kotani holds regular meetings in their house: they are apparently ‘friendly’ gambling games, but it soon becomes apparent that this is simply a front, and that Kotani is part of a gang who are blackmailing the attendees of these games. These attendees include Kawai, a pharmacist, and Muraoka, the owner of a pool hall. Asako begins to notice that both Kawai and Muraoka lose approximately the same amount each time they visit and play with Kotani (‘about 40,000 or 50,000 Yen every time’, she observes). Suspecting that the games are not what they are claimed to be, Asako asks her husband to conduct them elsewhere.

When Asako is asked to call Hamazaki, one of the regular players in the Kotani’s games, to notify him of the change of venue, Asako recognises Hamazaki’s voice immediately as the voice of the killer who taunted her several years earlier. Asako visits the Maicho newspaper offices to speak with Ishikawa, but finds herself followed by Hamazaki, who unbeknownst to her makes explicit plans to murder Asako. However, that evening Kotani returns home beaten and bloodied, telling Asako that he has cut his ties with Hamazaki and ‘beat up that gangster’.

When Hamazaki is found murdered the next day, Kotani becomes the primary suspect. However, Asako isn’t convinced: she tells Ishikawa that Kotani is not capable of murder, and Ishikawa promises to try to clear Kotani’s name. Speaking with the pharmacist Kawai, Ishikawa uncovers the exact nature of the blackmailing scam for which Hamazaki had enlisted the help of Kotani; Ishikawa’s investigations lead him to believing Muraoka is the culprit in Hamazaki’s murder. When Hamazaki is found murdered the next day, Kotani becomes the primary suspect. However, Asako isn’t convinced: she tells Ishikawa that Kotani is not capable of murder, and Ishikawa promises to try to clear Kotani’s name. Speaking with the pharmacist Kawai, Ishikawa uncovers the exact nature of the blackmailing scam for which Hamazaki had enlisted the help of Kotani; Ishikawa’s investigations lead him to believing Muraoka is the culprit in Hamazaki’s murder.

In the film’s opening sequence, when Asako connects to the telephone line over which she hears the murder, over her left shoulder we see a Hannya mask, a type of mask meant to represent a demon that is associated with Noh theatre. Similar compositions appear later in the film – Asako with identical masks behind her – as an index of impending danger. When Asako talks to Hamazaki on the telephone and recognises his voice as that of the killer, the same composition is repeated: Asako near the centre of the frame, and an identical (or near-identical) mask over her left shoulder. Asako’s recognition of Hamazaki’s voice after three years is met with incredulity by the police: as Asako tells Ishikawa, ‘No one believes I could remember a voice from three years ago’.

Voice Without a Shadow is anchored by narration from a number of characters. After the film’s depiction of the murder which took place three years prior to the main narrative, Ishikawa narrates over his encounter with Asako in the diegetic present, asserting that ‘It was definitely her. The first case I covered as a newspaper reporter three years ago [….] After hearing she had a fiancé I avoided seeing her. I heard she got married, but can it change a person this drastically?’ Later, after recognising Hamazaki’s voice, Asako narrates, fixing for the viewer her realisation that she is speaking to the murderer who taunted her in the film’s opening sequence.

The lover of Hamazaki’s accomplice Muraoka, Mari is a former dancer who is deliriously sadistic, laughing when Hamazaki tells her of his plan to murder Asako and gleefully strangling a dog in a bravura flashback sequence. This sequence begins with Ishikawa questioning Suzomoto, the owner of a miso and soy sauce shop who has provided Muraoka with an alibi for the night of Hamazaki’s murder. Suzomoto’s drunken recollections of that night are presented for us visually, signaled as potentially unreliable (in the manner of the famous ‘lying flashback’ from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, 1950) by the use of Dutch angle shots that communicate the sense of drunken disorientation experienced by the characters. Within the flashback, Mari is shown trying to strangle a terrified-looking dog, as Suzomoto’s wife declares ‘You look like you wouldn’t hurt a fly, but you’re trying to strangle that dog’. A later flashback, to the murder of Hamazaki itself, has a similar sense of disorientation and unease communicated visually through being shot in the reflection of a broken mirror; this flashback foregrounds the cruel Mari’s centrality to the murder of Hamazaki – not its perpetrator but certainly a key instigator. The lover of Hamazaki’s accomplice Muraoka, Mari is a former dancer who is deliriously sadistic, laughing when Hamazaki tells her of his plan to murder Asako and gleefully strangling a dog in a bravura flashback sequence. This sequence begins with Ishikawa questioning Suzomoto, the owner of a miso and soy sauce shop who has provided Muraoka with an alibi for the night of Hamazaki’s murder. Suzomoto’s drunken recollections of that night are presented for us visually, signaled as potentially unreliable (in the manner of the famous ‘lying flashback’ from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, 1950) by the use of Dutch angle shots that communicate the sense of drunken disorientation experienced by the characters. Within the flashback, Mari is shown trying to strangle a terrified-looking dog, as Suzomoto’s wife declares ‘You look like you wouldn’t hurt a fly, but you’re trying to strangle that dog’. A later flashback, to the murder of Hamazaki itself, has a similar sense of disorientation and unease communicated visually through being shot in the reflection of a broken mirror; this flashback foregrounds the cruel Mari’s centrality to the murder of Hamazaki – not its perpetrator but certainly a key instigator.

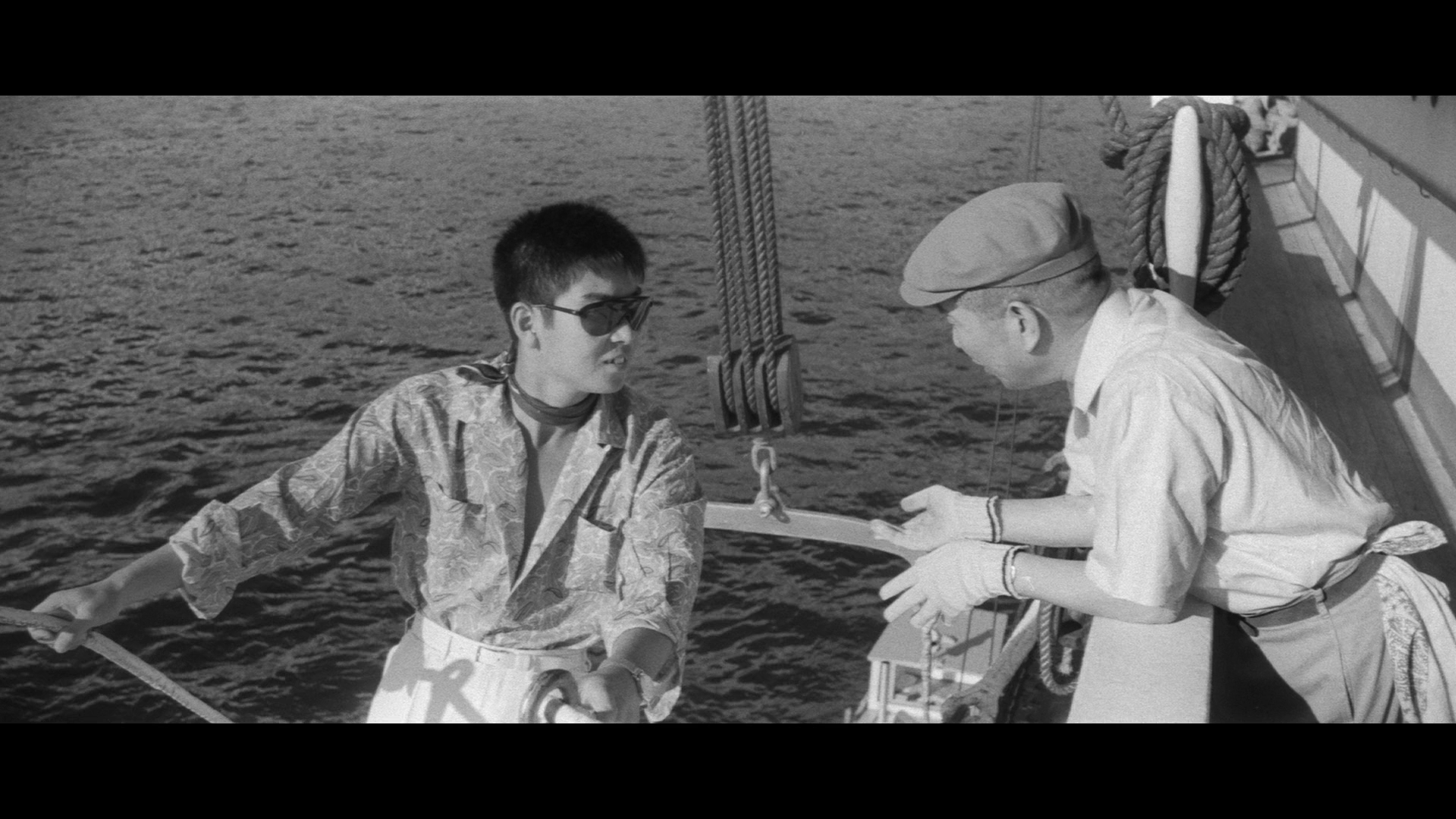

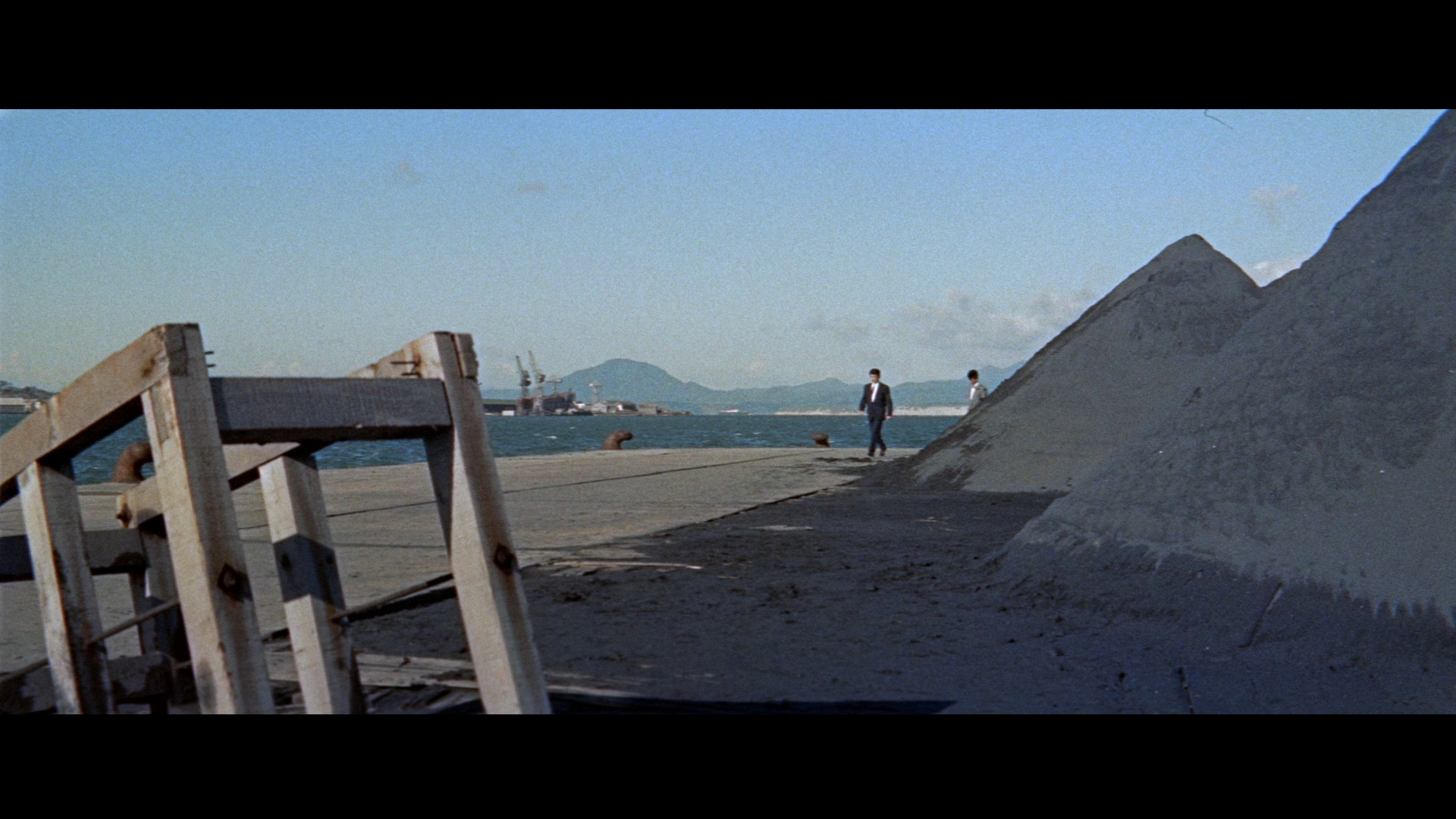

The director of the second film in this set, Red Pier (1958, also known in English as Red Quay), Masuda Toshio made his mark as a director for Nikkatsu with the 1958 picture Rusty Knife. Rusty Knife was Masuda’s third film, and was a big hit for the studio. In total Masuda made around 50 films for Nikkatsu during the late 1950s and 1960s. Masuda left the studio just before Nikkatsu became involved in making the Roman Porno pictures which characterised their output during the 1970s. One of the abiding features of Masuda’s films for Nikkatsu is his strong use of real locations rather than studio sets, and this is a feature that’s easily identifiable within Red Pier. Mark Schilling suggests that Red Pier is a loose remake of Julien Duvivier’s 1937 picture Pépé le Moko and was the film that ‘set the pattern’ for many of Nikkatsu’s subsequent borderless action films (Schilling, 2007: 23). Masuda later revisited the narrative of Red Pier, offering a loose remake of it in the form of his 1967 film Velvet Hustler (also released in the US as Like a Shooting Star), which combined elements of Red Pier with the influence of Jean-Luc Godard’s A bout de souffle (Breathless, 1959).

Red Pier opens at Kobe Port, where a trap is set for a man, Sugitaya. Sugitaya is lured to a bulk-handling crane, where he is killed with its shell grab in a manner that is clearly intended to look like an industrial accident. Sugitaya’s death has been engineered by Jiro on behalf of the Matsuyama gang; it’s later revealed that Sugitaya has been killed owing to his status as a drug pusher. Red Pier opens at Kobe Port, where a trap is set for a man, Sugitaya. Sugitaya is lured to a bulk-handling crane, where he is killed with its shell grab in a manner that is clearly intended to look like an industrial accident. Sugitaya’s death has been engineered by Jiro on behalf of the Matsuyama gang; it’s later revealed that Sugitaya has been killed owing to his status as a drug pusher.

Jiro’s life becomes complicated when he meets the beautiful Keiko. Jiro finds himself drawn to the young woman immediately, but soon discovers she is the sister of Sugitaya. At the Port Festival, Jiro meets with Keiko, but he’s spotted by one of his lovers, Mami, who becomes wracked with jealousy. Mami informs Keiko that her beloved brother was a drug dealer, and suggests that Jiro engineered Sugitaya’s murder.

Meanwhile, Jiro is double-crossed by a member of the Matsuyama family who attempts to seize power within the gang by hiring an assassin to kill Jiro, the favourite of the current – and currently desperately ill – head of the Matsuyama family. The hired killer, Tsuchida, murders Teko, one of Jiro’s closest friends, at another Port Festival. Jiro catches up with Tsuchida and kills him in revenge; Teko’s lover Michi takes the blame for the murder (‘I avenged my lover. Don’t get in my way’, Michi tells Jiro), although the police are sure it was carried out by Jiro. Jiro’s killing of Tsuchida draws out Katsumara, the enemy within the Matsuyama family. Jiro kills Katsumara, but cognisant of Jiro’s desire for Keiko, the police use Keiko to set a trap for Jiro.

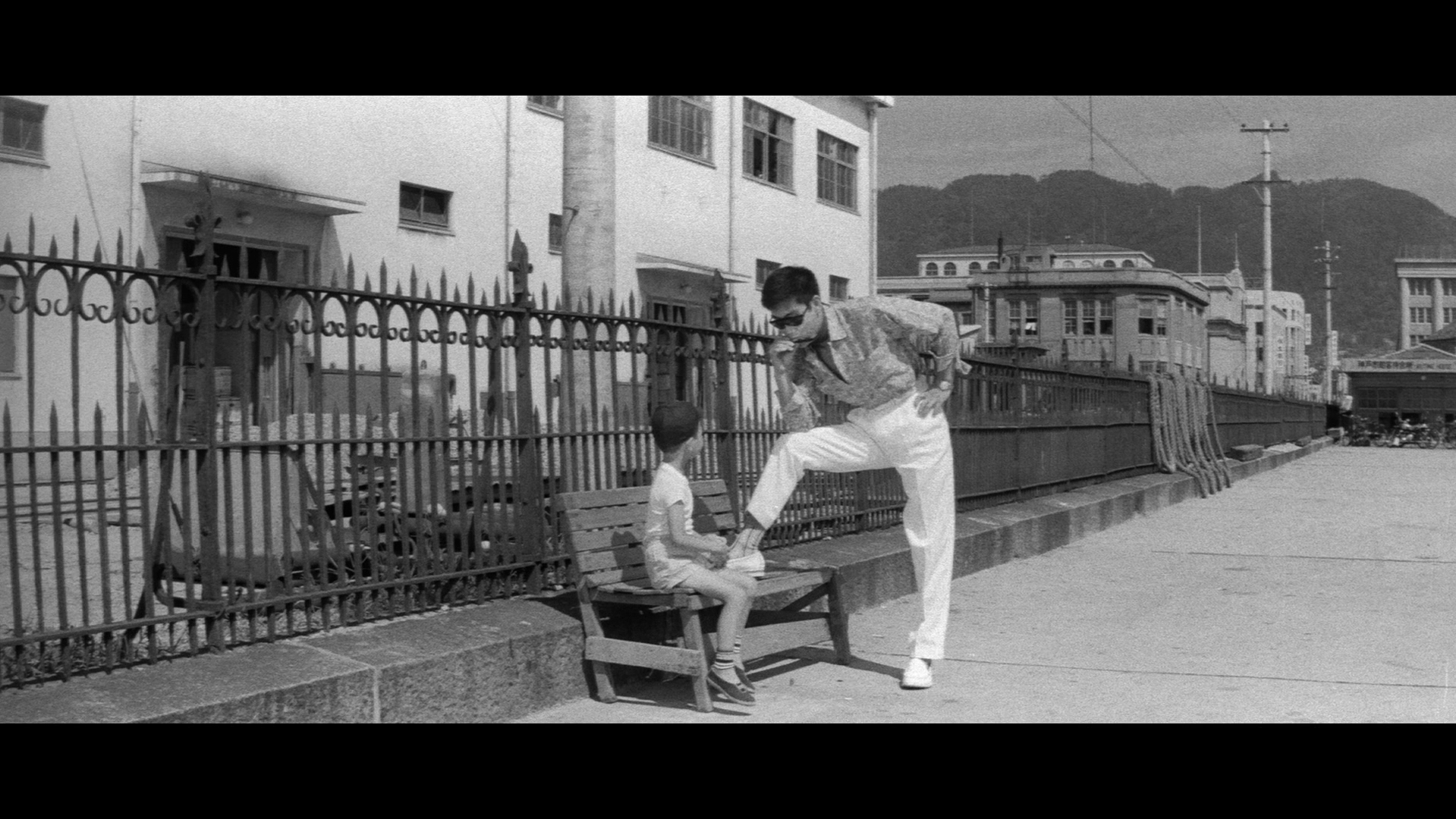

Jiro is introduced as an observer to the murder of Sugitaya, declaring dryly, ‘Nasty way to die’. However, immediately afterwards he risks his life in order to save a little boy from being hit by a car; Sugitaya slaps the car’s driver. His actions demonstrate that he’s a cold killer but also kind to children: this duality was at the core of many of the anti-heroes of the Nikkatsu borderless action films, which offered protagonists who were willing to eliminate enemies or rivals but who demonstrated a profound kindness towards children and ‘vulnerable’ women. In fact, at one point in the film Keiko is informed that Jiro is called “Lefty” because ‘even his men are afraid of him’, even though ‘He’s extremely kind to women and children’. The later revelation that Sugitaya was a drug peddler is clearly an attempt to retrospectively soften the callousness of Jiro in the opening sequence, but this is counterbalanced by Keiko’s assertion that following the death of their father, Sugitaya took out a loan to pay for Keiko’s education and was forced to deal drugs in order to pay it back – ‘And when he was just about to get out of it, he got killed’, Keiko says. Jiro is introduced as an observer to the murder of Sugitaya, declaring dryly, ‘Nasty way to die’. However, immediately afterwards he risks his life in order to save a little boy from being hit by a car; Sugitaya slaps the car’s driver. His actions demonstrate that he’s a cold killer but also kind to children: this duality was at the core of many of the anti-heroes of the Nikkatsu borderless action films, which offered protagonists who were willing to eliminate enemies or rivals but who demonstrated a profound kindness towards children and ‘vulnerable’ women. In fact, at one point in the film Keiko is informed that Jiro is called “Lefty” because ‘even his men are afraid of him’, even though ‘He’s extremely kind to women and children’. The later revelation that Sugitaya was a drug peddler is clearly an attempt to retrospectively soften the callousness of Jiro in the opening sequence, but this is counterbalanced by Keiko’s assertion that following the death of their father, Sugitaya took out a loan to pay for Keiko’s education and was forced to deal drugs in order to pay it back – ‘And when he was just about to get out of it, he got killed’, Keiko says.

Jiro is dismissive of the ‘easy’ women with whom he mixes. Early in the film he is shown giving the ‘blow off’ to Mami, telling her, ‘I don’t like women who argue pointlessly’. When he meets Keiko, Jiro realises that they have very different backgrounds but is drawn to her nonetheless. It could be said that Jiro is afflicted by the Madonna/whore complex: he’s unsatisfied with endless bar girls but desires the pretty, cultured Keiko, who comes from a wealthy family in Tokyo. When Jiro asks Keiko what her favourite bar in Shinjuku is, she underscores the cultural differences between them by responding, ‘Favourite bar? We usually had tea and went to the movies’. Keiko mentions a restaurant, Ran, as a particular favourite of hers; Jiro is familiar with the restaurant but declares that ‘They have stuck-up waiters there’. Later, Keiko is warned about Jiro that ‘He is living in a world you could never imagine. Don’t forget that’.

In light of this, Mami’s assertion upon discovery of Jiro’s burgeoning relationship with Keiko that she ‘owns’ Jiro seems fatalistic, hinting at how impossible it is for Jiro to escape from his past: ‘I’m not going to let you go’, Mami tells Jiro after discovering his interest in Keiko, ‘No one can take you away from me! You’re mine!’. Jiro desires to escape, telling Keiko ‘how I wish to go across the ocean where nobody knows me’. Declaring that he is ‘so sick of this life’, Jiro suggests to Keiko that he believes himself to be fated to his position as a criminal: he was a homeless child, and ‘I was in a gang from the start. So I don’t know any other way of life’. Later, he discusses his status as a yakuza with Keiko, who suggests he could simply ‘throw the gun away’ – the gun operating as a symbol for Jiro’s ties to his criminal lifestyle. ‘I can’t help it’, Jiro tells her pathetically, ‘I was born to be a yakuza. Ever since I was born, I’ve been deep into this mess. Without guns, a person won’t survive. Someone like you, from a good family, wouldn’t understand’. In light of this, Mami’s assertion upon discovery of Jiro’s burgeoning relationship with Keiko that she ‘owns’ Jiro seems fatalistic, hinting at how impossible it is for Jiro to escape from his past: ‘I’m not going to let you go’, Mami tells Jiro after discovering his interest in Keiko, ‘No one can take you away from me! You’re mine!’. Jiro desires to escape, telling Keiko ‘how I wish to go across the ocean where nobody knows me’. Declaring that he is ‘so sick of this life’, Jiro suggests to Keiko that he believes himself to be fated to his position as a criminal: he was a homeless child, and ‘I was in a gang from the start. So I don’t know any other way of life’. Later, he discusses his status as a yakuza with Keiko, who suggests he could simply ‘throw the gun away’ – the gun operating as a symbol for Jiro’s ties to his criminal lifestyle. ‘I can’t help it’, Jiro tells her pathetically, ‘I was born to be a yakuza. Ever since I was born, I’ve been deep into this mess. Without guns, a person won’t survive. Someone like you, from a good family, wouldn’t understand’.

Aware of Jiro’s love for Keiko, and sure that Jiro will throw away his chance to escape with Mami – who has prepared a boat which will take Jiro away from the city – the police use Keiko as bait to set a trap for Jiro. ‘A cornered man is like an injured beast’, the detective hunting Jiro asserts, ‘He can’t think straight. He will come to the one he loves most. I’m not the smartest, but I can see that’. To trap Jiro, the police publish a story in the newspaper that suggests Keiko has been rushed to hospital. Jiro takes the opportunity to kill three members of the Matsuyama family before heading to the hospital to see Keiko. Reinforcing the cultural distance between the couple, though he has the opportunity to enter the building to speak with Keiko, Jiro instead stands outside and watches her through the window, a perpetual outsider to Keiko’s bourgeois life. As he is led away by the police, Jiro simply asks them to ‘Do me a favour. Please don’t give her a hard time’.

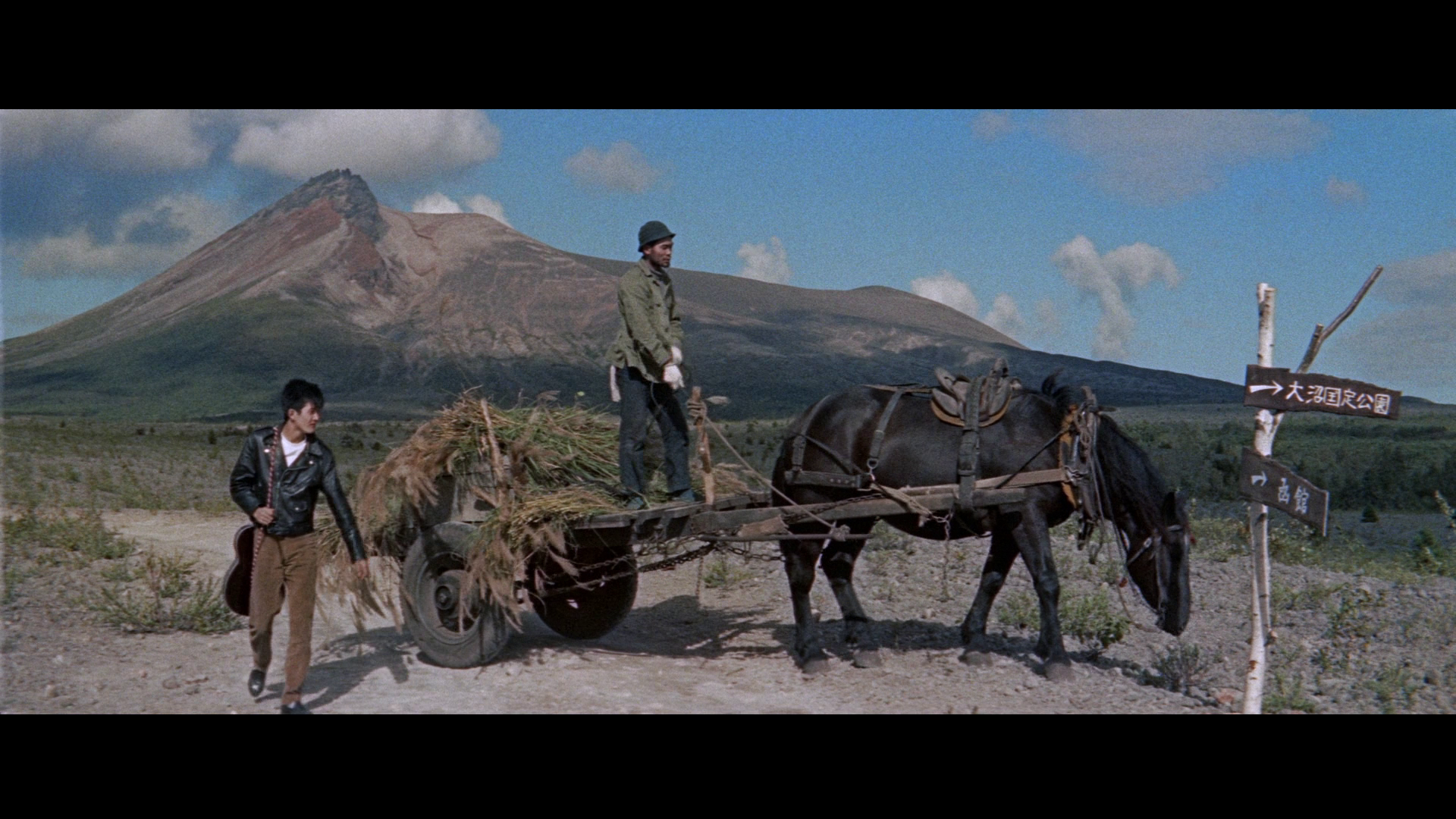

The mukokuseki akushon pictures could veer between the outlandish and camp (for example, Hasebe Yasuhara’s Black Tight Killer, 1966) and moody film noir-esque pictures. In terms of the films in this set, Voice Without a Shadow and Red Pier represent the latter trend: they are fatalistic pictures, shot in a recognisable film noir style with bold chiaroscuro lighting and the use of obtuse angles in the photography. The final film in the set, Saito Buichi’s The Rambling Guitarist (1959) is something of a contrast to these two films: it’s shot in colour and, at least in its opening sequences depicting the guitar-carrying Taki’s arrival in the town of Hakodate, seems to ape the American Western. The film’s mixture of music and action strongly recalls American youth pictures, particularly those of Elvis Presley. It’s a stark contrast to the first two films in the set but evidence of the flexibility of the studio’s approach to filmmaking. The mukokuseki akushon pictures could veer between the outlandish and camp (for example, Hasebe Yasuhara’s Black Tight Killer, 1966) and moody film noir-esque pictures. In terms of the films in this set, Voice Without a Shadow and Red Pier represent the latter trend: they are fatalistic pictures, shot in a recognisable film noir style with bold chiaroscuro lighting and the use of obtuse angles in the photography. The final film in the set, Saito Buichi’s The Rambling Guitarist (1959) is something of a contrast to these two films: it’s shot in colour and, at least in its opening sequences depicting the guitar-carrying Taki’s arrival in the town of Hakodate, seems to ape the American Western. The film’s mixture of music and action strongly recalls American youth pictures, particularly those of Elvis Presley. It’s a stark contrast to the first two films in the set but evidence of the flexibility of the studio’s approach to filmmaking.

The Rambling Guitarist, sometimes discussed under the title Guitar Wanderer, was the first of a series of nine wataridori (‘wanderer’) films made by Nikkatsu and starring Kobayashi Akira that was sparked by the success of Masuda Toshio’s We Live Today in 1959. We Live Today had been heavily based on George Stevens’ ‘adult’ Western Shane (1953), and the influence of Westerns runs throughout the ‘wanderer’ pictures: as Mark Schilling states, ‘[t]he Wanderer films were modelled on Hollywood Westerns, right down to [star Kobayashi] Akira’s guitar, boots, fringes and horse’ (Schilling, op cit.: 15-6). In total, Nikkatsu made nine ‘wanderer’ pictures starring Kobayashi, including Saito Buichi’s Plains Wanderer (1960) and Suzuki Seijun’s Kanto Wanderer (1963). Interviewed by Mark Schilling, Masuda responded to the suggestion that Red Pier and some of his other films were very similar to Hollywood films noir and though they ‘were shot in Japan, […] the settings weren’t typically Japanese’ by asserting, ‘I guess you could say that, but they were still set in Japanese society’ (Masuda, quoted in Schilling, op cit.: 127). Masuda goes on to suggest that in contrast with films like Red Pier, The Rambling Guitarist, owing to the way it was shaped by the American Western and the Hollywood youth film, ‘was a totally borderless film’ (Masuda, quoted in ibid.).

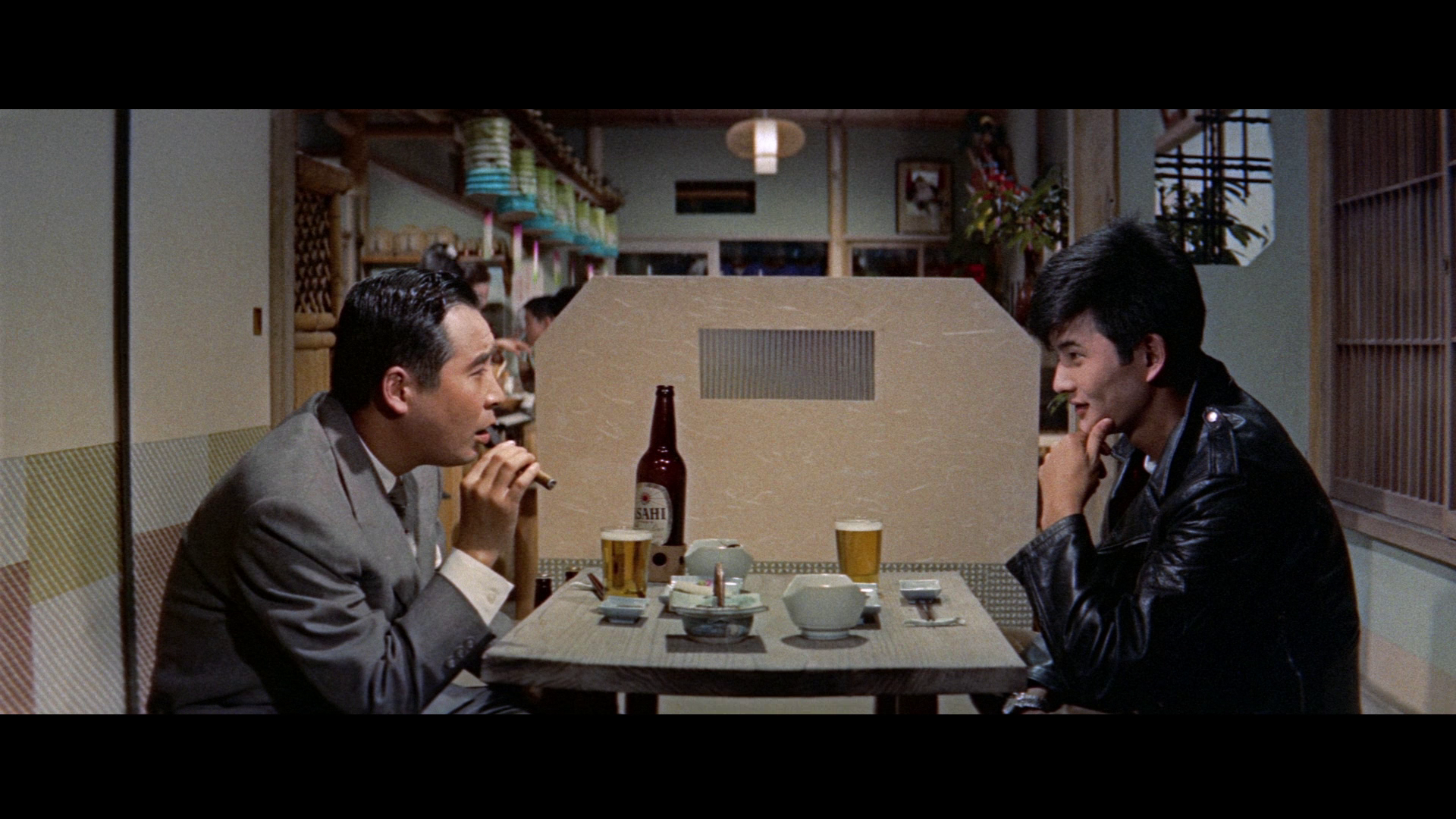

Reflecting the influence of American Westerns like Shane, The Rambling Guitarist begins with the film’s hero, Taki Shinji, walking through the countryside carrying only his guitar. (On the audio track, the lyrics of a poppy song accompany his lonely wandering by declaring, ‘Carrying his guitar / With no destination in mind’.) Shinji arrives in the town of Hakodate and quickly establishes his ability to fight when he witnesses an accordion player accosted in a bar; Shinji defends the accordion player against a group of thugs. Following the fight, Shinji is introduced to Akitsu, a local businessman and, as we will shortly discover, gangster. Akitsu offers Shinji a job. Akitsu plans to build a big amusement park in a nearby fishing village, but this involves acquiring the land for the site from the family that own it. Akitsu uses Shinji and the others to strongarm the family, who own Akitsu a significant sum of money; they are gradually revealed to be Akitsu’s own sister and her good-for-nothing husband. Reflecting the influence of American Westerns like Shane, The Rambling Guitarist begins with the film’s hero, Taki Shinji, walking through the countryside carrying only his guitar. (On the audio track, the lyrics of a poppy song accompany his lonely wandering by declaring, ‘Carrying his guitar / With no destination in mind’.) Shinji arrives in the town of Hakodate and quickly establishes his ability to fight when he witnesses an accordion player accosted in a bar; Shinji defends the accordion player against a group of thugs. Following the fight, Shinji is introduced to Akitsu, a local businessman and, as we will shortly discover, gangster. Akitsu offers Shinji a job. Akitsu plans to build a big amusement park in a nearby fishing village, but this involves acquiring the land for the site from the family that own it. Akitsu uses Shinji and the others to strongarm the family, who own Akitsu a significant sum of money; they are gradually revealed to be Akitsu’s own sister and her good-for-nothing husband.

Shinji grows closer to Akitsu’s pretty daughter but is warned off by both Akitsu and Shinji’s own cognisance of the cultural gulf that exists between them. Meanwhile, Shinji is introduced to George, who is on secondment from another yakuza family. George recognises Shinji from somewhere but can’t quite place him, until during an assignment George realises that Shinji is a former ‘cop from Kobe’ who killed George’s friend. George vows to enact revenge against Shinji. When the corpse of Akitsu’s brother-in-law is found in the harbour, the stage is set for a showdown between Shinji, George and Akitsu.

In the opening sequence of the film, the nods to the visual and thematic conventions of American Westerns come thick and fast: a lone hero wandering out of the wilderness into an unfamiliar town, a bar/saloon where the hero demonstrates his selflessness by defending someone less fortunate than himself, the recognition of the hero’s fighting abilities resulting in the villain’s attempt to recruit him, and so on. In these sequences, the picture has the emotional intensity and tabloid sensibility evidenced in a film like Samuel Fuller’s powerful Forty Guns (1957). For his part, with his leather jacket and guitar Shinji looks like a rocker; his costume alludes to the iconography of American youth pictures such as the Elvis Presley films. Like Jiro in the previous film, Shinji is quickly established as a character who looks kindly upon children. Wandering through Hakodate, Shinji encounters a little boy who is crying because he has lost his balloons. Shinji wanders over to a vendor and buys some more balloons for the child as well as some sweets, but returning to the spot where the boy was crying Shinji discovers the child’s mother has ushered him away. In the next scene, Shinji is shown playing guitar in a bar, the balloons tied to the neck of his instrument. The balance of youthful rebellion and moral certainty within Shinji is thus quickly established by the film.

Shinji is initially reticent to become involved with Akitsu’s business, telling the gangster that ‘I appreciate the offer [of a job] but I’ll pass. I don’t tend to settle in one place’. However, Shinji’s initial resistance to working for Akitsu is gradually eroded. ‘It’s the same wherever I go’, Shinji tells Akitsu in one scene, commenting on the ways in which Hakodate seems to be overrun by gangsters. ‘It’s not the same’, Akitsu assures him. However, upon accepting Aktisu’s proposition, Shinji reinforces his moral code: ‘I hate bullying the weak’, Shinji asserts, and Akitsu tells Shinji that the job he has in mind is very different. Shinji is initially reticent to become involved with Akitsu’s business, telling the gangster that ‘I appreciate the offer [of a job] but I’ll pass. I don’t tend to settle in one place’. However, Shinji’s initial resistance to working for Akitsu is gradually eroded. ‘It’s the same wherever I go’, Shinji tells Akitsu in one scene, commenting on the ways in which Hakodate seems to be overrun by gangsters. ‘It’s not the same’, Akitsu assures him. However, upon accepting Aktisu’s proposition, Shinji reinforces his moral code: ‘I hate bullying the weak’, Shinji asserts, and Akitsu tells Shinji that the job he has in mind is very different.

As in Red Pier, the cultural differences between the film’s anti-hero and the woman he pursues romantically are established from the outset. In Akitsu’s house, Shinji hears Akitsu’s daughter playing Chopin on the family piano. He criticises her playing before playing a few bars of Chopin himself; one of Akitsu’s gangsters is impressed with this, telling Shinji, ‘I knew you weren’t some kind of rat’. ‘Even rats know Chopin’, Shinji responds humbly. However, Akitsu’s daughter’s feelings are hurt: she’s considered an excellent pianist. Later, intrigued by Shinji, Akitsu’s daughter asks him to act as her bodyguard whilst she goes shopping. She asks Shinji what he used to do; ‘Don’t say wandering’, she warns him. ‘Unfortunately, that’s all I can do’, Shinji responds. ‘Liar’, she says, ‘Someone like that wouldn’t know Chopin’. ‘Someone I knew loved Chopin’, he tells her, ‘That’s how I knew him’. When Akitsu’s daughter asks Shinji if this person ‘was a woman? Did you love her?’, Shinji tells her that his lover died two years earlier. Shinji and Akitsu’s daughter end up dancing in a café, but Shinji tells her, ‘You shouldn’t hang around someone like me [….] I come from a different world than you do’. Shinji is soon warned away from Akitsu’s daughter by Akitsu himself; and George also tells Shinji, ‘You shouldn’t mess around with women. They’ve caused the downfall of many men’.

The differences between Shinji and Akitsu’s daughter are mirrored in the differences between Akitsu’s sister and her husband. Akitsu’s brother-in-law is a no-hoper, and Akitsu grumbles to Shinji that his sister ‘refused the marriage I prepared for her and married that coward instead. She ignored by wishes’; Akitsu suggests that the taking of their land will ‘be a well-deserved lesson’ for both of them. Akitsu has no qualms about ordering the murder of his own brother-in-law, and as Akitsu’s sister notes, this seems to have been engineered with the intention that she will have no options other than to work for Akitsu. Later in the film, after the murder of Akitsu’s brother-in-law, George sexually assaults Akitsu’s sister; Akitsu walks into the room after the fact and, realising what has taken place but utterly nonchalant in the face of it, declares coldly that he didn’t know George was attracted to her. The realisation that Akitsu ordered the murder of her uncle causes Akitsu’s daughter to recognise the duality that exists within her father: ‘I know now’, she says, ‘You were a perfect father to me but a demon to the rest of the world’. ‘Everything I do is for your happiness’, Akitsu tells her. ‘I don’t need that kind of happiness’, she asserts pithily. The differences between Shinji and Akitsu’s daughter are mirrored in the differences between Akitsu’s sister and her husband. Akitsu’s brother-in-law is a no-hoper, and Akitsu grumbles to Shinji that his sister ‘refused the marriage I prepared for her and married that coward instead. She ignored by wishes’; Akitsu suggests that the taking of their land will ‘be a well-deserved lesson’ for both of them. Akitsu has no qualms about ordering the murder of his own brother-in-law, and as Akitsu’s sister notes, this seems to have been engineered with the intention that she will have no options other than to work for Akitsu. Later in the film, after the murder of Akitsu’s brother-in-law, George sexually assaults Akitsu’s sister; Akitsu walks into the room after the fact and, realising what has taken place but utterly nonchalant in the face of it, declares coldly that he didn’t know George was attracted to her. The realisation that Akitsu ordered the murder of her uncle causes Akitsu’s daughter to recognise the duality that exists within her father: ‘I know now’, she says, ‘You were a perfect father to me but a demon to the rest of the world’. ‘Everything I do is for your happiness’, Akitsu tells her. ‘I don’t need that kind of happiness’, she asserts pithily.

The three films are interesting: all of them possess the ‘international’ flavour of Nikkatsu’s productions of this period, and there’s some overlap between their content: the first two pictures are moody film noir-esque monochrome productions, and the latter film is a more buoyant colour production; however, thematically Red Pier and The Rambling Guitarist are connected by their close focus on the yakuza milieu and their examination of the conflict between a patriarchal crime boss and a younger, more moral anti-hero. Each picture has a doom-laden romance at its centre too, which reinforces the theme of cultural difference that exists within these films (between criminals and ‘straight’ society, between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’) and the impossibility of movement between these worlds.

Video

Presented on a single dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the films take up approximately 14Gb, 15Gb and 13Gb respectively. All three pictures are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. (The films were shot in anamorphic widescreen.) Presented on a single dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the films take up approximately 14Gb, 15Gb and 13Gb respectively. All three pictures are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. (The films were shot in anamorphic widescreen.)

The 35mm monochrome photography within Voice Without a Shadow and Red Pier is communicated very nicely within this presentation, with an excellent level of detail present. Contrast levels are very nicely balanced, with strong midtones present which taper off into shadow, underscoring the films’ use of film noir-esque chiaroscuro lighting. (A good example here is the opening shot of Voice Without a Shadow, which features the switchboard operator at her desk, her face illuminated but shadow surrounding her, as if threatening to swallow her.) The Rambling Guitarist’s colour photography is equally handsomely presented here: the opening sequence features a beautiful juxtaposition of the earthy tones of the ground with the bold blue of the sky. (There are bursts of vibrant colour throughout the film – for example, the primary colours of the young boy’s balloons in the sequence mentioned above.) Red Pier seems to evidence some subtly noticeable density fluctuations within the film’s emulsions but nothing that’s too distracting.

All three films seem to have been shot with short focal lengths throughout, resulting in an image which has a very strong depth of field, reinforced by movement from foreground to background of the frame. (This sometimes emphasises the barrel distortion associated with the wide angle lenses, especially of this vintage; this can be seen, for example, in the slow dolly through Akaboshi’s pawnshop near the beginning of Voice Without a Shadow.) This sense of depth is captured in these HD presentations very well. All three films seem to have been shot with short focal lengths throughout, resulting in an image which has a very strong depth of field, reinforced by movement from foreground to background of the frame. (This sometimes emphasises the barrel distortion associated with the wide angle lenses, especially of this vintage; this can be seen, for example, in the slow dolly through Akaboshi’s pawnshop near the beginning of Voice Without a Shadow.) This sense of depth is captured in these HD presentations very well.

All three films have a pleasingly organic, film-like appearance that is facilitated by a strong encode to disc.

Voice Without a Shadow runs for 91:45 mins; Red Pier runs for 98:50 mins; and The Rambling Guitarist runs for 77:24 mins.

NB. Some larger screen grabs from all three films are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

For all three films, audio is presented via a Japanese LPCM 1.0 track. In all three cases, this is clear, with good depth and range. Optional English subtitles are provided for the three pictures, and these are clear and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes:

- ‘Introduction to the Diamond Guys’. This comprises two interviews with Jasper Sharp, one focusing on Ishihara Yujiro (15:24) and the other examining Nitani Hideaki (10:20). In the first of these interviews, Sharp talks about Nikkatsu’s work generally and the development of the studio to the point of the production of the three films included in this set. He discusses Ishihara’s work as an actor and suggests that the performer ‘was very much like the Japanese Elvis’. In the second interview, Sharp focuses on Nitani’s work, suggesting that Nitani was ‘slightly more anonymous’ than some of the other Nikkatsu actors. Sharp spends some time talking about Voice Without a Shadow specifically and highlighting the ways in which Suzuki’s later pictures overshadow some of his more ‘pulpy’ earlier films.

- Trailers for Voice Without a Shadow (3:08), Red Pier (3:22) and The Rambling Guitarist (3:18), plus trailers for the films to appear in Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol. 2 (11:46).

- Galleries for Voice Without a Shadow (0:21), Red Pier (0:30) and The Rambling Guitarist (0:41).

Overall

The three pictures in Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol. 1 set are deliciously pulpy examples of the ‘international’ flavour of the studio’s output during the late 1950s and into the 1960s. They’re moody, magnificent and thoroughly entertaining films. Voice Without a Shadow and Red Pier are most obviously linked through their film noir aesthetic, but all three pictures share a sense of fatalism and rebellion which was obviously intended to chime with youth audiences at the time of their production. In their self-conscious pastiche of Hollywood forms (and their nightclub scenes), the pictures have a lot in common with the self-referential adoption of Hollywood’s film noir tropes in the work of European filmmakers like Jean-Pierre Melville, for example. All three pictures get a handsome presentation in this Blu-ray set from Arrow, with some good contextual material in the form of the interviews with Jasper Sharp that are included on the disc. The three pictures in Arrow’s Nikkatsu Diamond Guys, Vol. 1 set are deliciously pulpy examples of the ‘international’ flavour of the studio’s output during the late 1950s and into the 1960s. They’re moody, magnificent and thoroughly entertaining films. Voice Without a Shadow and Red Pier are most obviously linked through their film noir aesthetic, but all three pictures share a sense of fatalism and rebellion which was obviously intended to chime with youth audiences at the time of their production. In their self-conscious pastiche of Hollywood forms (and their nightclub scenes), the pictures have a lot in common with the self-referential adoption of Hollywood’s film noir tropes in the work of European filmmakers like Jean-Pierre Melville, for example. All three pictures get a handsome presentation in this Blu-ray set from Arrow, with some good contextual material in the form of the interviews with Jasper Sharp that are included on the disc.

References:

Schilling, Mark, 2007: No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming: FAB Press

Voice Without a Shadow

Red Pier

The Rambling Guitarist

|